Mysteries of the Green Sahara and the foundations of Africa’s ancient kingdoms (ca. 10,000-3,500BC)

Around 5,000 years ago, the Sahara was a lush, humid landscape with a chain of lakes and waterways linking West, East, and North Africa in what is known as the African Humid Period.

For thousands of years, landscapes that are today extremely inhospitable were covered with grasslands and rainforests, with a rich variety of flora and fauna, and complex human societies. But at the end of the African humid period, the rains disappeared, the lakes dried up, and the Sahara became the world’s largest desert.

Saharan societies coped with the new ecological setting by moving to its less-arid edges, inventing cereal Agriculture, and making the first attempts at civilization along the eastern, southern, and northern ends of the desert. The landscape began to be marked by diverse types of funerary architecture as social hierarchies were formed and social complexity increased, laying the foundations for the emergence of Africa’s ancient kingdoms.

This article outlines the latest research on the Green Sahara period and examines its significance to the emergence of Africa’s agriculture, population movements, and complex societies.

Map of the Green Sahara showing some of the sites mentioned in the article.1

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Ancient communities of the Green Sahara between Gobero and Lake Mega-Chad.

The Sahara is Earth’s largest hot desert, covering about one-third of the African continent. Over the past millennia, the Sahara has undergone strong climatic fluctuations, alternating between arid and wet phases. The last significant wet phase was in the Early-Mid Holocene period from 10,000 to 3,500 BC. During this humid period, referred to as the “Green Sahara,” the landscape was characterized by the presence of Savannah, forests, and an extensive system of rivers and lakes.2

Human activity during the Green Sahara is demonstrated in numerous rock engravings and occupation sites, bearing evidence for the development of food production strategies and increasing socio-economic complexity. But much of what is known about the communities that lived in the Green Sahara comes from a handful of exceptionally preserved burial sites in the northern parts of modern Mali and Niger.

The most significant of these burial sites was found in the region of Gobero in modern Niger, which is the largest and oldest graveyard in the Sahara. Archaeologists uncovered the remains of hundreds of individuals and numerous objects in Gobero, as well as in the neighbouring sites of the Tenere massif and Adrar n’Kiffi, which was located near an ancient lake in the Adrar Bous. The finds indicate that the burials belonged to at least two main cultural complexes: an older culture known as the Kiffian, and a later Pastoral culture known as the Tenerian.3

‘Shoreline of a former lake at Adrar Bous in the heart of the Sahara. The irregular brown material on the surface of the sandy beach-ridge consists of fossilised reeds. Shells of freshwater snails are scattered through the beach sands’4

Aerial view of Gobero sites with an excavation team for scale (center right). The raised site on the bottom left (G3) served both funerary and habitation functions since the Kiffian period.5

The Kiffian culture consisted of hunter-gather communities, with a microlithic industry (small stone tools), bone tools (points, harpoons), and rare pottery decorated with dotted wavy lines. Radiocarbon dating of human remains places burial activities into two primary occupation phases, separated by a harsh arid spike. The first is attributed to the Kiffian period from 7600BC to 5360 BC ( 9550-7310 BP) at sites such as Temet, Tagalagal, and Adrar n’Kiffi. The succeeding period, known as the Tenerian, lasted from 3480 BC to 1620 BC (5430-3570 BP).6

Unlike the Kiffians, the Tenerian communities were associated with food production and animal herding. One of the typical Tenerian burials was found at Agorass in-Tast in the Adrar Bous. It contains the remains of two well-preserved human burials, alongside the remains of burned animal bones with associated stone tools, charcoal, and pottery, which appear to be the remains of meals. The vertebra of a giraffe was found near the head of one of the burials, as well as eggshell beads, several remains of cattle, and pieces of grinding stones. 7

Gobero was located near the western fringes of the Mega-Chad lake, a large inland sea about 10 times the size of the modern Lake Chad, whose fluctuations likely affected the Kiffian and Tenerian communities.

The first phases of the Mega-Chad lake's expansion occurred between the 7th and 6th millennia BC. This could have affected the Pre-Pastoral kiffian sites nearest to the lake, some of whom would have migrated to drier regions, before it was possible to settle again in the area, then by Pastoral groups. The latter communities provide evidence for the earliest herding economies in the region, but both were engaged in extensive fishing activity on the mega-Chad lake and its rivers.8

For example, a wooden canoe dating to 6500 BC was found at Dufuna in northern Nigeria, and is considered the second oldest boat in the world. It has a length of 8.40 m and a maximum breadth and height of around 0.5 m, and its bow and stern are pointed. The vessel’s relatively elegant form indicates that it was a product of an established boat-building tradition, and was preceded by a long period of development in the watercraft of the Green Sahara’s communities.9

The dufuna canoe. Image from Wikimedia Commons

The Pastoral period of the Sahara: Rock Art, Population movements and Incipient states

The last sub-phase of expansion of the Mega-Chad lake is dated to the 5th millennium BC, after which local climatic conditions progressively deteriorated. Pastoral groups spread throughout the Gobero area —the earliest domesticated cattle remains at the site are dated to the early 4th millennium BC (5890–5610 BP). The Pastoral groups included cultures that were contemporaneous with but unrelated to the Tenerian communities. These are identified by the differences in their material culture and the absence of Tenerian-style disks and pottery at sites like Chin Tafidet, Ikawaten, and other sites in Niger.10

Additional evidence of prehistoric cattle herding among the communities of the Green Sahara comes from the remarkable collection of rock paintings and engravings across the region, possibly the world’s largest concentration of prehistoric art, long known for their rich and vivid portrayal of scenes from everyday life.11

This pictorial record extends from Egypt to Mauritania, and includes not just depictions of cattle (introduced after 6000 BC), but also images of other domesticates like horses, which were introduced much later (after 2000BC), and thus makes the artwork notoriously difficult to date. Nevertheless, some of the drawings can be attributed to the Green Sahara period, given the inclusion of animals like giraffes and hippos that don’t thrive in desert environments.12

Map of the Sahara showing the main mountain systems and the major rock art concentrations13

‘Oxen are held by tethers with well-drawn strands and are accompanied by dogs. Engraved group in Wâdi Tidûwa, Messak Mellet (Fezzân, Libya).’14

Scene of cattle with men, women, and children. Tassili n’Ajjer, Algeria.15

Engraving depicting human figures, stock animals, and giraffes. Tanakom, East Air, Niger.16

Giraffe carvings at Dabous, west Air, Niger. Image by Bradshaw Foundation.

Human figures depicted in the large fresco of Ouri, Chad. 17

‘Map of early sites for cattle in Saharan Africa’18

While population movements across the Green Sahara may have facilitated the spread of cattle, sheep, and horses, direct evidence for such migrations is still lacking since genetic data from the over 200 Gobero burials in Niger hasn’t been extracted.

The only ancient DNA study conducted for this period comes much further north, at the Libyan site of Takarkori, dated to the 4th millennium BC, where genetic data from 2 burials indicated no southern links, but shared affinities with populations in north-west Africa, showing that some of the ancient communities remained relatively isolated.19

However, studies of the human remains from Uan Muhuggiag in Libya and Nabta Playa in Egypt (see map in introduction), which indicate affinities with modern groups living south of the Sahara, suggest that there was northward movement of human populations into the Green Sahara.20 Additionally, the Pre-Pastoral inhabitants of Gobero likely spoke a language related to the Nilo-Saharan macrophylum, which developed around 20–30,000 years ago. The subsequent Pastoral groups could have included speakers of both Nilo-Saharan (eg, Kanuri and Songhai) and proto-Afroasiatic languages (eg, Hausa) that make up the modern languages of Niger.21

Monumental tombs in the Sahara also appeared during this period, beginning at Emi Lulu, in north-eastern Niger, dated to 4700–4200 BC. This tradition would proliferate during the 3rd millennium BC, especially in the Aïr, Ténére, and Adrar Bous regions, which contained large tumuli burials featuring numerous animal sacrifices reserved for privileged members of the society. These burials indicate an articulated social hierarchy and a cattle cult similar to that found in the Nile valley (at Kerma, Sudan), Libya (at Messak), and in Mali’s Tilemsi valley.22

The archaeologist Kevin MacDonald suggests that this early Saharan pastoral complexity was a harbinger of sedentary African states. He argues that the construction of monumental tumuli was evidence of inequality, with cattle serving as repositories of wealth in long-distance exchanges between elites within the communities of the Green Sahara, which at varying points in time would eventually develop into the hierarchical societies of the Nile Valley and the Tichitt tradition.23

Monument with corridor and enclosure, EL 2-7, Emi Lulu necropolis, Niger.24

Tomb at Bazina, Areschima, Niger.25

View of a tomb with sculpted monoliths. Aïr, Niger. British Museum. This site is located close to the Anakom and Tanakom rock engravings sites.

Necropolis in the Ténére, Niger.26

Tumulus at Oued Essendilène; Bazina, Areshima; and Anakom in Niger.27

The invention of Agriculture in Africa: Pearl millet and the Neolithic traditions of West Africa

The Tilemsi valley is of key interest for the study of agricultural development in West Africa, providing the earliest archaeobotanical evidence for domesticated pearl millet, one of the continent's most important cereals.

The Tilemsi valley contains several occupation sites and tumuli dated to between 2800-1800BC, with most sites clustering between 2400-2200BC. It also contained a fully articulated cow burial and clay figurines of cows. The material recovered from these sites includes faunal assemblages that indicate the presence of aquatic animals (fish, crocodiles, turtles), as well as pottery sherds tempered with chaff, which contain fragments of domesticated pearl millet dated to 2400BC.28

More recent research in northern Mali indicates that the process of domesticating pearl millet began in the 5th millennium BC, with a gradual increase in grain sizes by 28% in the 4th millennium BC, and by 38% during the third millennium BC. Once domesticated, pearl millet spread widely and rapidly south and east, reaching eastern Sudan by 1850 BC and the Indian subcontinent, via maritime links, by 1700 BC.29

This rapid rate of spread may well have been aided by the suitability of this grain for cultivation by mobile pastoralist societies and the crop’s minimal water requirements. The spread of domesticated pearl millet also coincided with the beginning of major cultural and economic transformations along the southern edge of the Sahara, marked by the appearance of several Neolithic traditions.

Increased climatic deterioration enhanced competition and specialisation among the different groups. As the now arid regions of the Sahara, such as Gobero, were abandoned, some of these groups moved south into the Lake Chad basin to form the Neolithic tradition at Gajiganna.30

Locations of the Gajiganna, Tichitt, Nok, and Kintampo Neolithic traditions mentioned below.31

Numerous sites of the Gajiganna Culture (1,800 to 800 BC) yielded plant impressions in potsherds. The bulk of these sherds belong to Phase II (1,500–800 BC) and were tempered with chaff derived from domesticated pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum), as well as wild rice species (Oryza cf. barthii and O. cf. longistaminata). Archaeologists suggest that the knowledge of agricultural practices was introduced from outside the region, likely by migrating agropastoralists from the Sahara.32

Cereal agriculture was extant from the very advent of the Neolithic Tichitt Tradition in Mauritania (1900-400 BC), whose historical connection to Saharan communities is displayed in its funerary architecture and herding economy.

Pottery sherds tempered with pearl millet were recovered from the earliest Tichitt phase (1900-1600 BC), indicating that pearl millet was farmed during this period, especially in Dhar Nhema at Djiganyai (1750-1530 BC). But it’s unclear whether the domesticates arrived as a fully formed agro-pastoral economic package from elsewhere, since the grain impressions are absent on the pottery of the pre-Tichitt phase (2600–1900 BC).33

One of the two funerary monuments of Dakhlet el Atrouss 1, east of Akreijit. Image by R. Vernet.

Domesticated Pearl millet is also present in the earliest levels of the Nok culture of Nigeria, which is divided into three phases: Early Nok (1500–900 BC), Middle Nok (900–400 BC), and Late Nok (400–1 BC). Unlike the Tichitt and Gajiganna sites, where pearl millet remains are mainly known from impressions in ceramics, the material from Nok includes caryopses (grains) whose size indicates that the crop was already fully domesticated by the time the ancient Nok farmers adopted it.34

While the neolithic cultures of Gajiganna and Tichitt share with the Tilemsi sites a rich sculptural tradition that prominently features depictions of bovines, the famous sculptural art of the Nok culture contains no depictions of domesticated animals (although all art traditions featured numerous zoomorphic figures).35 Despite claims that mobile herders from the drying Sahara established the Nok tradition, most of it lies just north of the equator and is quite distant from the Sahara. Its acidic tropical soil dissolved most organic matter, including animal bones, leaving no direct evidence for pastoralists in the Neolithic tradition.36

Nok sculpture depicting a harvest scene, Middle Nok period (900–300 BC). Quai Branly

Pearl millet was also found in the Kintampo Neolithic complex of Ghana, which, like the Nok culture, is also located along the Savanna/Forest boundary, and presents the earliest confirmed evidence for the use of domestic resources in the region. Material recovered from the Kitampo site of Birimi included the remains of domesticated pearl millet grains dated to 3490 BP (1878-1744 BC), as well as the earliest evidence for domesticated cowpea (1830-1595 BC), which also rapidly spread eastwards as far as India by 1500 BC.37

Like in the Tichitt and Nok sites, evidence for pearl millet from the Kitampo sites was obtained from the oldest occupation phases of the Neolithic tradition, indicating that the domestication process predates its emergence. However, unlike its contemporaries, the linkages between the Saharan sites and the Kintampo tradition are still a subject of intense debate.

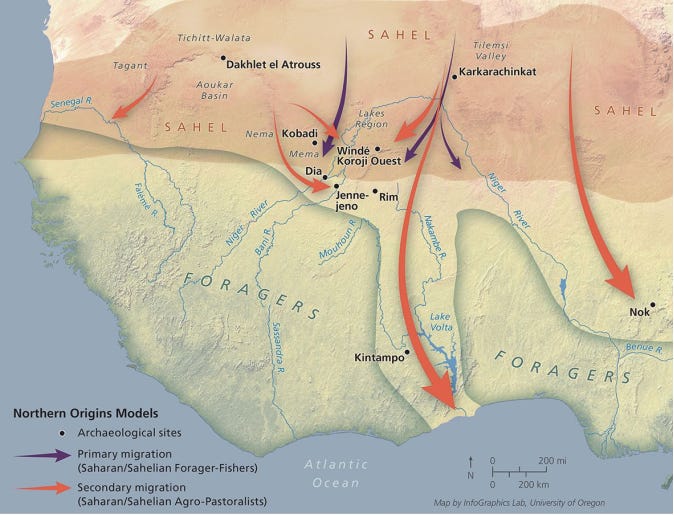

‘Visualization of northern origins model for agricultural expansion.’ Map by Stephen Dueppen.

Alternative paths to the Agricultural revolution in Africa.

The presence of Saharan domesticates (millet and cattle) initially led some scholars to argue for a northern origin of the Kitampo complex. However, more recent thinking envisions the Kintampo as a fusion of northern imported and local elements, based on continuity in cultural development evident in the archaeological record. The Kintampo complex was thus part of a diversified landscape of expanding agro-pastoral communities contemporary with those of Tichitt, Nok, and Gajiganna.38

It’s also important to note that several crops were domesticated in the savannah and forest zones of West Africa, and that other Neolithic traditions emerged in this region that were unrelated to the Sahara's desiccation, eg, the central African Neolithic sites of Gabon at Okanda, dated to 2100-1700 BCE.39 Domesticates from the forest margins include yams, kola, and oil palm, while those from the savannah include African rice, cowpea, Bambara groundnut, sorghum, and the fonio cereals, with the Saharan zone only producing Pearl millet.40

‘Probable geographic locations of the five centres of indigenous crop domestication in Africa, on a topographic base map. (A) West African Sahara/Sahel: pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) and possibly watermelon. (B) West African grassy woodlands: fonio cereals, cowpea, Bambara groundnut, African rice (Oryza glaberrima), and baobab. (C) Forest margins: West African yams, oil palm and kola. (D) East Sudanic grasslands: sorghum and possibly hyacinth bean. (E) Uplands of Ethiopia (t’ef, enset, noog, coffee, yams, and possibly finger millet) and eastern Africa (an alternative location for finger millet domestication).’41

Map showing some of the Neolithic sites of West and Central Africa by Sylvain Ozainne. Note that sites: 28 in Mauritania (Tichitt), 14 in Ghana (Kintampo), 30 in Nigeria (Gajiganna), and 13 in Gabon (Okanda) are all dated to the early 2nd millennium BC.

Recent research also uncovered newer sites from the Neolithic period that undermine theories of unidirectional flows of population from the drying Sahara.

Excavations from the site of Bosumpra in Ghana, which is south of the Kitampo sites (see map below), recovered pottery fragments dated to the 11th-10th millennium BC, which is slightly older than the previously oldest known pottery on the continent obtained from the site of Ounjougou on the Bandiagara Plateau in Dogon country, Mali. Pottery traditions would emerge much later among the communities of the Green Saharan period, with pottery sherds being found in the Central Saharan sites of Tagalagal, Temet, and Adrar Bous, dated to the 8th millennium BC, and at Nabta Playa (Egypt) from the 8th-7th millennium BC.42

The Bosumpra pots were decorated with twine roulette techniques often associated with the later Saharan/Sahelian Neolithic ceramics, which also challenges models favouring a southward diffusion. There is also direct evidence for the presence of domesticated pearl millet and cowpeas dated to the early 2nd millennium BC and 1st millennium BC, which is just as old, if not older than the Kintampo, Tichitt, Nok, and Gajiganna sites. Additionally, the combination of evidence for arboriculture (vegetal oils from incense tree and oil palm) and pottery may indicate that the domestication of yams in the savannah/forest started much earlier than previously thought.43

According to the archaeologist Stephen Dueppen “given the technologies in use (ceramics, axes for forest clearance, probable salt production) and the cultural practices (ancestral rituals, large sites with durable architecture, etc.), some of which predate the Kintampo complex by millennia, as well as the fact that yams and other forest domesticates are challenging to identify archaeologically, it is far more likely that agriculture has similar antiquity in the south as in the north.”44

‘Proposed network model with expanded agricultural activity.’ Map by Stephen Dueppen.

By the 2nd-1st millennium BC, desertification became an irreversible process, and the Sahara-Sahel border progressively moved southwards. This process occurred at different times in different places, and in the case of West Africa, may have occurred through two abrupt phases of desiccation around 2000–1500 BC and 500 BC.45

The economies of Africa's Neolithic societies became increasingly complex with the advent of ironworking and the expansion of iron-using farmers into areas that had been too humid or heavily forested.

In the early centuries of the common era, these internal processes gave rise to the emergence of cities, kingdoms, and empires that dominated the landscape of medieval West Africa. Some of these empires would eventually expand into the now arid Sahara, in the land of their ancient progenitors, where they would rediscover the ancient paintings of the Green Sahara.

Ennedi, Chad.46

My latest article explores the development of Asante’s ornamented architecture, whose foundations lay in the rectilinear constructions of the ancient communities of Ghana, and undermines earlier theories that traced the origins of such building styles to North Africa.

Please subscribe to read more about it here:

.

Map by Carl Churchill, modified by Author.

The climate-environment society nexus in the Sahara from prehistoric times to the present day, by Nick Brooks et al, Burials, Migration and Identity in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond edited by M. C. Gatto, D. J. Mattingly, N. Ray, M. Sterry pg 2

The Archaeological Significance of Gobero By Elena A. A. Garcea pg 5-8

When the Sahara Was Green: How Our Greatest Desert Came to Be, By Martin Williams, pg 97

Lakeside Cemeteries in the Sahara: 5000 Years of Holocene Population and Environmental Change by Paul C. Sereno et al.

The Archaeological Significance of Gobero By Elena A. A. Garcea pg 8-9, 12-15, An archaeological perspective on the burial record at Gobero by CM Stojanowski 44-46 for earlier date ranges see: Lakeside Cemeteries in the Sahara: 5000 Years of Holocene Population and Environmental Change by Paul C. Sereno

The Archaeological Significance of Gobero By Elena A. A. Garcea pg 8-9

Regional Overview During the Time Frame of the Gobero Occupation by Elena A.A. Garcea, pg 251-256

New Research on the Holocene Settlement and Environment of the Chad Basin in Nigeria, by Peter Breunig et al.

Regional Overview During the Time Frame of the Gobero Occupation by Elena A.A. Garcea, pg 256-257, Gobero: The Secular and Sacred Place by Elena A.A. Garcea, pg 272-273

Saharan Rock Art: Archaeology of Tassilian Pastoralist Iconography by Augustin F.C. Holl, Round Heads: The Earliest Rock Paintings in the Sahara by Jitka Soukopova, An Engraved Landscape: Rock carvings in the Wadi al-Ajal, Libya: 2 Volume Set by Tertia Barnett, Ennedi, Tales on stone. Rock art in the Ennedi massif by Roberta Simonis, Adriana Ravenna, Pier Paolo Rossi

Forgotten Africa: An Introduction to Its Archaeology By Graham Connah pg 34-38, on the challenges of dating Saharan rock art: The date and context of Neolithic rock art in the Sahara: engravings and ceremonial monuments from Messak Settafet (south-west Libya) by Savino di Lernia, Marina Gallinaro, pg 955-958,

The date and context of Neolithic rock art in the Sahara: Engravings and ceremonial monuments from Messak Settafet (south-west Libya), by Marina Gallinaro and Savino Di Lernia

“Hunters” and “Herders” in the Central Sahara: the “Archaic Hunters” expelled from the Paradigm by Jean-Loïc Le Quellec

The Highlands of the Sahara, c. 8000–c. 2000 BCE by W. W. Norton

Rock art of Sahara and North Africa: thematic study by Susan Denyer et al (ICOMOS), pg 173

Rock art of Sahara and North Africa: thematic study by Susan Denyer et al (ICOMOS), pg 184

Landscapes and Landforms of the Central Sahara, edited by Jasper Knight, Stefania Merlo, Andrea Zerboni

Ancient DNA from the Green Sahara reveals ancestral North African lineage. Nada Salem et al. Ancestral mitochondrial N lineage from the Neolithic ‘green’ Sahara by Stefania Vai et al.

Funerary practices and anthropological features at 8000–5000 BP. Some evidence from central-southern Acacus (Libyan Sahara)’ by S. di Lernia and G. Manzi, pg 217-238. Human Skeletal Remains from Three Nabta Playa Sites by Joel D. Irish

Gobero: The Secular and Sacred Place by Elena A.A. Garcea, pg 274

Regional Overview During the Time Frame of the Gobero Occupation by Elena A.A. Garcea pg 256-266, Les Sépultures du Sahara Nigérien du Néolithique à l’Islamisation by François Paris, Inside the “African Cattle Complex”: Animal Burials in the Holocene Central Sahara by Savino di Lernia, The First Herders of the West African Sahel: Inter-site Comparative Analysis of. Zooarchaeological Data from the Lower Tilemsi Valley, Mali, by Katie Manning

Before the Empire of Ghana: Pastoralism and the origins of cultural complexity in the Sahel by Kevin MacDonald, Complex Societies, Urbanism, and Trade in the Western Sahel by Kevin MacDonald pg 829-831 in ‘Oxford. Handbook of African Archaeology, ed. Peter Mitchell’

Chronologie des monuments funéraires sahariens Problèmes, méthode et résultats, by François Paris and Jean-François Saliège

Deux modes d'inhumation néolithiques au Niger oriental, secteur d'Areschima by Jean-Pierre Roset

4500-Year old domesticated pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) from the Tilemsi Valley, Mali by Katie Manning et al. pg 314-317, The First Herders of the West African Sahel: Inter-site Comparative Analysis of. Zooarchaeological Data from the Lower Tilemsi Valley, Mali, by Katie Manning

Transition From Wild to Domesticated Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum) Revealed in Ceramic Temper at Three Middle Holocene Sites in Northern Mali by Dorian Q. Fuller pg 212

Regional Overview During the Time Frame of the Gobero Occupation by Elena A.A. Garcea, pg 260-262

The Oxford Handbook of African Archaeology, ed. P. Mitchell, pg 514

Four thousand years of plant exploitation in the Lake Chad Basin (Nigeria), part III: plant impressions in potsherds from the Final Stone Age Gajiganna Culture by Marlies Klee et al.

Dhar Néma: from early agriculture to metallurgy in southeastern Mauritania by Kevin C. MacDonald et al

A question of rite—pearl millet consumption at Nok culture sites, Nigeria (second/first millennium BC), by Louis Champion et al. Nok: African Sculpture in Archaeological Context, edited by Peter Breunig, pg 34-36

Early sculptural traditions in West Africa: new evidence from the Chad Basin of north-eastern Nigeria by Peter Breunig et al.

Nok: African Sculpture in Archaeological Context, edited by Peter Breunig, pg 33-37

Archaeobotanical evidence for pearl millet. (Pennisetum glaucum) In sub-Saharan West Africa, by A. C. D'Andrea et al. Early domesticated cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) from Central Ghana by AC D'Andrea

Reconnecting the Forest, Savanna, and Sahel in West Africa: The Sociopolitical Implications of a Long‑Networked Past, by Stephen Dueppen, pg 10-14. Archaeobotanical evidence for pearl millet. (Pennisetum glaucum) in sub-Saharan West Africa, by A. C. D'Andrea. M. Klee. Joanna Casey, pg 346-347

West and Central African Neolithic: Geography and Overview by Sylvain Ozainne pg 7744–7759 in Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology edited by Claire Smith

Domesticating Plants in Africa by Dorian Q. Fuller and Elisabeth Hildebrand, in The Oxford Handbook of African Archaeology, ed. P. Mitchell

The Oxford Handbook of African Archaeology, ed. P. Mitchell, pg 513

Bosumpra revisited: 12,500 years on the Kwahu Plateau, Ghana, as viewed from ‘On top of the hill’, by Derek J. Watson, pg 463-464. Early Pottery in Northern Africa - An Overview by Friederike Jesse.

Reconnecting the Forest, Savanna, and Sahel in West Africa: The Sociopolitical Implications of a Long‑Networked Past, by Stephen Dueppen, pg 11. 10,000-year history of plant use at Bosumpra Cave, Ghana by Sarah E. Oas et al. Bosumpra revisited: 12,500 years on the Kwahu Plateau, Ghana, as viewed from ‘On top of the hill’, by Derek J. Watson, pg 459

Reconnecting the Forest, Savanna, and Sahel in West Africa: The Sociopolitical Implications of a Long‑Networked Past, by Stephen Dueppen, pg pg 13

Urbanisation and State Formation in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond edited by Martin Sterry, David J. Mattingly pg 10-11

Ennedi, Pierres historiées. 1993-2017: Art rupestre dans le massif de l'Ennedi (Tchad). Ediz. illustrata. by Roberta Simonis et al.

Thanks for this especially since the AHP having been in the press a lot lately this was right on time, thank you always.

This history is covered and denied. You are lifting the veil for us thank you!