Reversing the Sail: a brief note on African travelers in the western Indian Ocean

The Swahili in Arabia and the Persian gulf

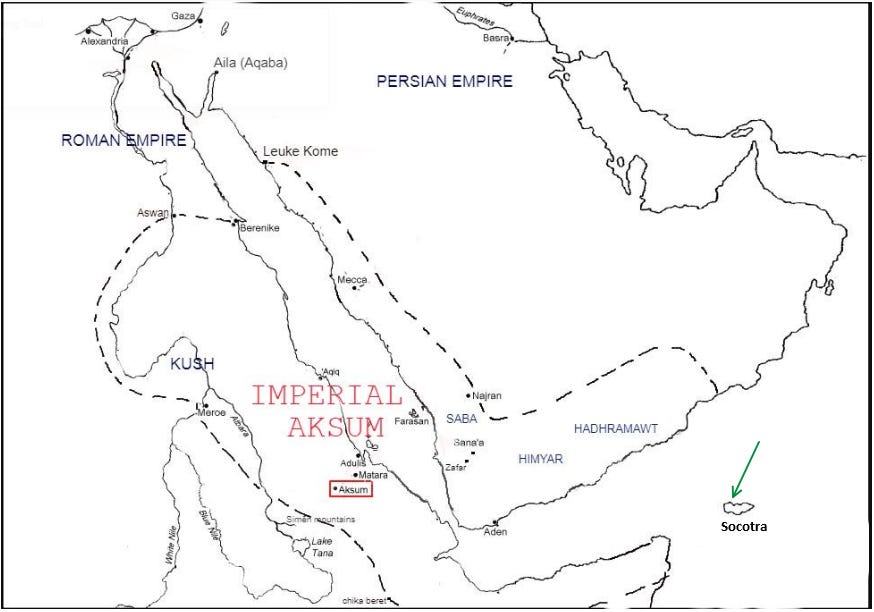

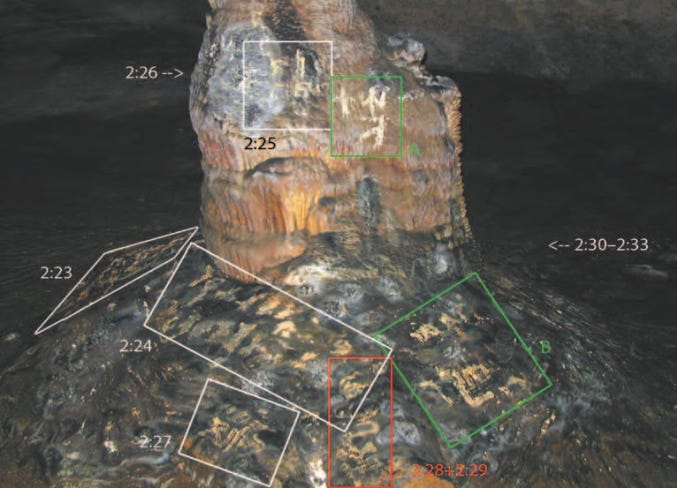

In December of 2000, a team of researchers exploring the island of Socotra off the coast of Yemen made a startling discovery. Hidden in the limestone caves of the island was a massive corpus of inscriptions and drawings left by ancient visitors from India, Africa, and the Middle East. At least eight of the inscriptions they found were written in the Ge'ez script associated with the kingdom of Aksum in the northern horn of Africa.

The remarkable discovery of the epigraphic material from Socotra is of extraordinary significance for elucidating the extent and scale of the Indo-Roman trade of late antiquity, which linked the Indian Ocean world to the Meditterean world. Unfortunately, most historiography regarding this period overlooks the role played by intermediaries such as the Aksumites who greatly facilitated this trade, as evidenced by Aksumite material culture spread across the region from the Jordanian city of Aqaba to the city of Karur in south-Eastern India.

The Aksumite Empire and the island of Socotra

one of the stalagmites bearing Aksumite, Brāhmī, and Arabian inscriptions.

The limited interest in the role of African societies in ancient exchanges reifies the misconception of the continent as one that was isolated in global processes. As one historian remarks; "Narratives of Africa’s relation to global processes have yet to take full account of mutuality in Africa’s global exchanges. One of the most complicated questions analysts of African pasts have faced is how African interests figure into an equation of global interfaces historiographically weighted toward the effects of outsiders’ actions."1

For the northern Horn of Africa in particular, ancient societies such as the Aksumites were actively involved in the political processes of the western Indian Ocean. Aksumite armies sent several expeditions into western Arabia from the 3rd to 6th century to support local allies and later to subsume the region as part of the Aksumite state. For nearly a century before the birth of the prophet Muhammad, much of modern Saudi Arabia was under the control of the Aksumite general Abraha and his successors. The recent discovery of royal inscriptions in Ge'ez commissioned by Abraha across central, eastern, northern, and western Arabia indicates that Aksumite control of Arabia was more extensive than previously imagined.

A few centuries later, the red-sea archipelago of Dahlak off the coast of Eritrea served as the base for the Mamluk dynasty of Yemen that was of 'Abyssinian' origin. From 1022 to 1159, this dynasty founded by an Abyssinian administrator named Najah controlled one of the most lucrative trade routes between the Red Sea and the western Indian Ocean. The Najahid rulers established their capital at Zabid in Yemen, struck their own coinage, and received the recognition of the Abbasid Caliph.

Around the same time the Abyssinians controlled western Yemen, another African community established itself along the southern coast of Yemen. These were the Swahili of the East African coast, a cosmopolitan community whose activities in the Indian Ocean world were extensive. The Swahili presence in Portuguese India in particular is well-documented, but relatively little is known about their presence in south-western Asia.

Cultural exchanges between East Africa and southwestern Asia are thought to have played a significant role in the development of Swahili culture, and resident East Africans in Arabia and the Persian Gulf were likely the agents of these cultural developments.

My latest Patreon article focuses on the Swahili presence in Arabia and the Persian Gulf from 1000 CE to 1900.

subscribe and read about it here:

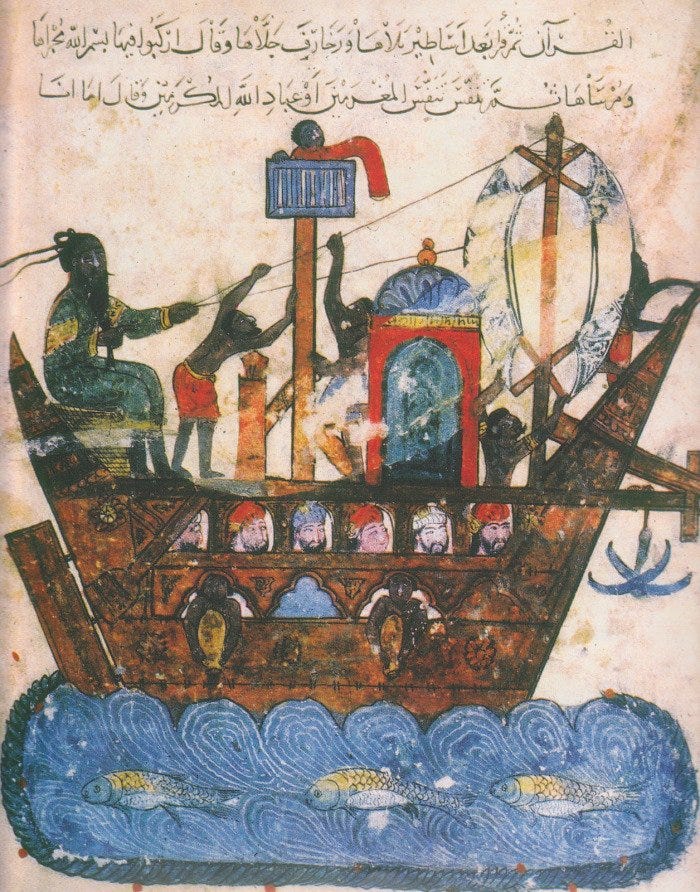

Illustration of a ship engaged in the East African trade in the Persian Gulf. 1237, Maqamat al-Hariri, The passengers are Arab, and the crew and pilot are East African and/or Indian. while the illustration doesn’t represent a specific type of ship, it is broadly similar to the sewn ships of the western Indian Ocean such as the mtepe of the Swahili.2

Domesticating the World: African Consumerism and the Genealogies of Globalization by Jeremy Prestholdt, pg5

Trade in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond edited by D. J. Mattingly pg 147

I appreciate the work you are putting in, I looked forward to Mondays when your updates comes out, thank you.