Seafaring, trade and travel in the African Atlantic. ca. 1100-1900.

historical links between West Africa and Central Africa. (Africans exploring Africa chapter 4)

Like all maritime societies, mastery of the ocean, was important for the societies of Africa's Atlantic coast, as was the mastery of the rest of their environment.

For many centuries, maritime activity along Africa's Atlantic coast played a major role in the region's political and economic life. While popular discourses of Africa's Atlantic history are concerned with the forced migration of enslaved Africans to the Americas, less attention is paid to the historical links and voluntary travel between Africa's Atlantic societies.

From the coast of Senegal to the coast of Angola, African seafarers traversed the ocean in their own vessels, exchanging goods, ideas, and cultures, as they established diasporic communities in the various port cities of the African Atlantic.

This article explores the history of Atlantic Africa's maritime activity, focusing on African seafaring, trade, and migration along the Atlantic coast.

Political map of Atlantic Africa in the 17th century1

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

State and society along the African Atlantic.

The African Atlantic was both a fishery and a highway that nurtured trade, travel, and migration which predated and later complemented overseas trade. Africans developed maritime cultures necessary to traverse and exploit their world. Coastal and interior waters enabled traders, armies, and other travelers to rapidly transport goods, people, and information across different regions, as well as to seamlessly switch between overland, riverine, and sea-borne trade to suit their interests.

Mainland West Africa is framed beneath the river Niger’s arch and bound together by an array of watercourses, including the calm mangrove swamps of Guinea and Sierra Leone. The Bights of Benin and Biafra’s lagoon complex extends from the Volta River, in what is now Ghana, to the Nigerian–Cameroonian border. Similarly, West-Central Africa was oriented by its rivers, especially the Congo and Kwanza rivers, in a vast hydrographic system that extended into the interior of central Africa. 2

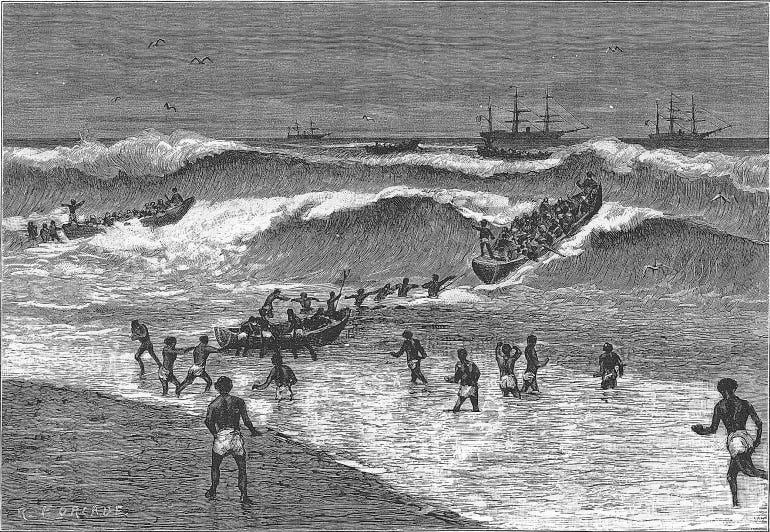

In many parts of West and Central Africa, different kinds of vessels were used to navigate the waters of the Atlantic, mainly to fish, but also for war and trade. When the Portuguese first reached the coast of Malagueta (modern Liberia) in the early 1460s they were approached by "some small canoes" which came alongside the Portuguese ships. On the Gold Coast (modern Ghana), it was noted of Elmina in 1529, that "the blacks of the village have many canoes in which they go fishing and spend much time at sea." While on the Loango coast, a visitor in 1608 noted that locals “go out in the morning with as many as three hundred canoes into the open sea”.3

Canoes were Atlantic Africans’ solution for navigating diverse waterways between the ocean, lagoons, and rivers. Many of these canoes were large and sea-worthy, measuring anywhere between 50-100ft in length, 5ft wide, and with a capacity of up to 10 tonnes. The size and design of these vessels evolved as Africans interacted with each other and with foreign traders. In the Senegambia and the Gold Coast, large watercraft were fitted with square sails, masts, and rudders that enabled them to sail out to sea and up the rivers.4

For most of its early history, the Atlantic coast of West Africa was dominated by relatively small polities on the frontiers of the large inland states like the Mali empire, and the kingdoms of Benin and Kongo, which were less dependent on maritime resources and trade than on the more developed resources and trade on the mainland.

The relatively low maritime activity by these larger west and central African states —which conducted long-distance trade on the mainland— was mostly due to the Atlantic Ocean’s consistent ocean currents, which, unlike the seasonal currents of the Indian Ocean, only flowed in one direction all year round. This could enable sailing in one direction eg using the Canary Current (down the coast from Morocco to Senegal), the Guinea Current (eastwards from Liberia to Ghana), and the Benguela Current (northwards from Namibia to Angola), but often made return journeys difficult5.

Map of Africa’s ocean currents6

The African Atlantic was thus the domain of the smaller coastal states and societies whose maritime activities, especially fishing, date back a millennia before the common era.7 While many of their coastal urban settlements are commonly referred to as “ports,” this appellation is a misnomer, as the Atlantic coast of Africa possesses few natural harbors and most “ports” were actually “surf-ports,” or landings situated on surf-battered beaches that offered little protection from the sea, and often forced large ships to anchor 1-5 miles offshore. Canoemen were thus necessary for the transportation of goods across the surf and lagoons.8

An overview of African maritime activity in the Atlantic

The maritime activities of African mariners appear in the earliest documentation of West African coastal societies. As early as the 15th century coastal communities in Atlantic Africa were documented using surf-canoes to transport goods to sea. Portuguese sailors off the coast of Liberia during the 1470s reported: “The negroes of all this coast bring pepper for barter to the ships in the canoes in which they go out fishing.” While another trader active in the Ivory Coast during the 1680s, noted that “Negroes in three Canoa’s laden with Elephant’s Teeth came on Board” his ship.9

Senegambian mariners transported kola nuts down the Gambia river, into the ocean, and along the coast to “the neighborhood of Great and Little Scarcies rivers, [in Sierra Leone] a distance of three hundred miles.” Similarly, as early as the 12th century, watercraft from the mouth of the Senegal River could journey up the Mauritanian coast (presumably to Arguin) from where they loaded salt brought overland from Ijil10. Overlapping networks of maritime and inland navigation sustained coastwise traffic from Cape Verde (in Senegal) to Cape Mount (in Liberia), bringing mainly kola nuts and pepper northwards.11

View of Rufisque, the capital of Cayor kingdom, Senegambia region, in 1746, showing various types of local watercraft.

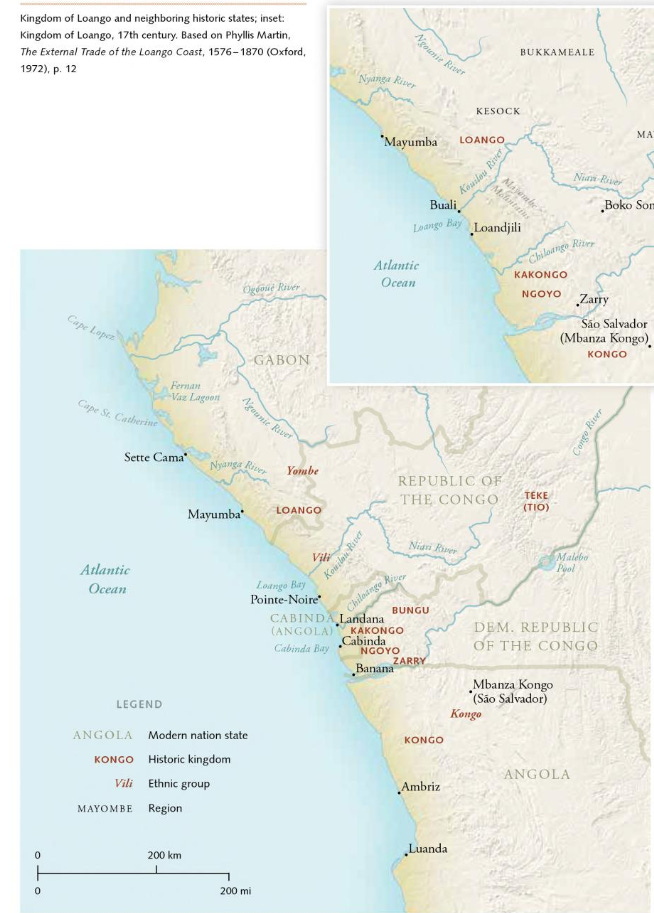

Similarly in west-central Africa, traders from as far as Angola journeyed northwards to Mayumba on the Loango coast, a distance of about 400 miles, to buy salt and redwood (tukula) that was ground into powder and mixed with palm oil to make dyes.12 The Mpongwe of Gabon carried out a substantial coastal trade as far north as Cameroon according to an 18th century trader. Mpongwe canoes were large, up to 60ft long, and were fitted with masts and sails. With a capacity of over 10 tonnes, they regularly traveled 300-400 miles, and according to a 19th-century observer, the Mpongwe’s boats were so well built that they "would land them, under favorable circumstances, in South America".13

However, it was the mariners of the Gold Coast region who excelled at long-distance maritime activity and would greatly contribute to the linking of Atlantic Africa’s regional maritime systems and the founding of diasporic communities that extended as far as west-central Africa. Accounts indicate that many of these mariners, especially the Akan (of modern Ghana and S.E Ivory Coast), and Kru speakers (of modern Liberia), worked hundreds of miles of coastline between modern Liberia and Nigeria. 14

The seafarers of the Gold Coast.

The practice of recruiting Gold Coast canoemen for service in the Bight of Benin appears to have begun with the Dutch in the 17th century. The difficult conditions on the Bight of Benin (between modern Togo and S.W Nigeria) made landing impossible for European ships, and the local people lacked the tradition of long-distance maritime navigation. The Europeans were thus reliant on canoemen from the Gold Coast for managing the passage of goods and people from ship to shore and back through the surf.15

“Surf-Canoes. Capturing the difficulty of launching and landing surf-canoes in storm-swept breakers, scenes like this convinced ship captains not to attempt such passages in their slower, less responsive shipboats, or longboats, but to instead hire African canoemen.”16

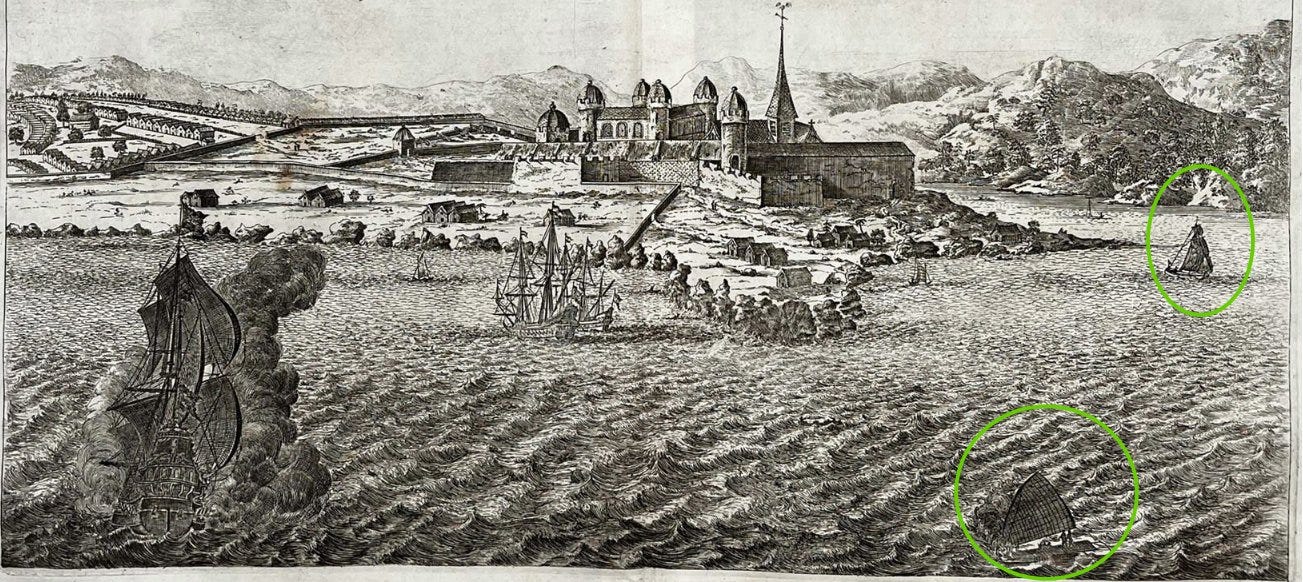

Gold coast mariners journeying beyond their homeland were first documented in an anonymous Dutch manuscript from the mid-17th century, in a document giving instructions for trade at Grand Popo (in modern Benin): "If you wish to trade here, you must bring a new strong canoe with you from the Gold Coast with oarsmen, because one cannot get through the surf in any boat".17

In the 18th century, the trader Robert Norris also observed Fante canoemen at Ouidah (in modern Benin), writing that “Landing is always difficult and dangerous, and can only be effected in canoes, which the ships take with them from the Gold Coast: they are manned with fifteen or seventeen Fantees each, hired from Cape Coast or El Mina; hardy, active men, who undertake this business, and return in their canoe to their own country, when the captain has finished his trade.”18

Another 18th-century trader, John Adams who was active at Eghoro along the Benin river in south-western Nigeria, wrote that "A few Fante sailors, hired on the Gold coast, and who can return home in the canoe when the ship's loading is completed, will be found of infinite service in navigating the large boast, and be the means of saving the lives of many of the ship's crew."19

These canoemen who traversed the region between south-eastern Ivory Coast and south-western Nigeria, were mostly Akan-speaking people from the gold coast and would be hired by the different European traders at their settlements. Most came from the Dutch fort at El-mina, but some also came from the vicinity of the English fort at Anomabo. At the last port of call, the canoemen would be released to make their way back to the Gold Coast, after they had received their pay often in gold, goods, and canoes.20

Gold Coast mariners were also hired to convey messages between the different European forts along the coast. Their services were particularly important for communications between the Dutch headquarters at El-Mina and the various out-forts in the Gold Coast and beyond. This was due to the prevailing currents which made it difficult for European vessels to sail from east to west, and in instances where there were no European vessels. Communication between Elmina and the outforts at Ouidah and Offra during the late 17th century was often conducted by canoemen returning home to the gold coast in their vessels21.

18th century engraving of El-mina with local sail-boats.

Regular route of the Gold coast Mariners

African Trade and Travel between the Gold Coast and the Bight of Benin.

The long-distance travel between the Gold Coast and the Bight of Benin stimulated (or perhaps reinvigorated) trade between the two regions.

This trade is first documented in 1659 when it was reported that ‘for some years’ the trade in ‘akori’ beads (glass beads manufactured in Ife), which had earlier been purchased by the Europeans from the kingdoms of Allada and Benin, for re-sale on the Gold Coast in exchange for gold, had been monopolized by African traders from the Gold Coast, who were going in canoes to Little Popo and as far as Allada to buy them. Another French observer noted in 1688 that Gold Coast traders had tapped the trade in cloth at Ouidah: ‘the Negroes even come with canoes to trade them, and carry them off ceaselessly.’22

Mariners from the Gold Coast were operating as far as the Benin port of Ughoton and possibly beyond into west-central Africa. In the 1680s, the trader Jean Barbot noted that Gold Coast mariners navigated “cargo canoes” using “them to transport their cattle and merchandise from one place to another, taking them over the breakers loaded as they are. This sort can be found at Juda [Ouidah] and Ardra [Allada], and at many places on the Gold Coast. Such canoes are so safe that they travel from Gold Coast to all parts of the Gulf of Ethiopia [Guinea], and beyond that to Angola.”23

Some of these mariners eventually settled in the coastal towns of the Bight of Benin. A document from the 1650s mentions a ‘Captain Honga’ among the noblemen of the king of Allada, serving as the local official who was the “captain of the boat which goes in and out.” By the 1690s Ouidah too boasted a community of canoemen from Elmina that called themselves 'Mine-men'. Traditions of immigrant canoemen from El-mina abound in Little Popo (Aneho in modern Togo) which indicates that the town played an important role in the lateral movement of canoemen along the coast. The settlement at Aneho received further immigrants from the Gold Coast in the 18th century, who created the different quarters of the town, and in other towns such as Grand Popo and Ouidah.24

As a transshipment point and a way station where canoemen waited for the right season to proceed to the Gold Coast, the town of Aneho was the most important diasporic settlement of people from the Gold Coast. External writers noted that the delays of the canoemen at Aneho were due to the seasonal changes, particularly the canoemen’s unwillingness to sail at any other time except the Harmattan season. During the harmattan season from about December to February, winds blow north-east and ocean currents flow from east to west, contrary to the Guinea current’s normal direction.25

Sailboat on Lake Nokoue, near the coast of Benin, ca. 1911, Quai branly

African seafaring from the Gold Coast to Angola.

The abovementioned patterns of wind and ocean currents may have facilitated travel eastwards along the Atlantic coast, but often rendered the return journey westwards difficult before the Gold Coast mariners adopted the sail. That the Gold Coast mariners could reach the Bight of Benin in their vessels is well documented, but evidence for direct travel further to the Loango and Angola coast is fragmentary, as the return journey would have required sailing out into the sea along the equator and then turning north to the Gold coast as the European vessels were doing.26

The use of canoemen to convey messages from the Dutch headquarters at El-mina to their west-central African forts at Kakongo and Loango, is documented in the 17th century. According to the diary of Louis Dammaet, a Dutch factor on the Gold Coast, in 1654, small boats could sail from the Gold Coast to Loango, exchange cargo, and return in two months. Additionally, internal African trade between West Africa and west-central Africa flourished during the 17th century. Palm oil and Benin cloth were taken from Sao Tome to Luanda, where it would be imported into the local markets. Benin cloth was also imported by Loango from Elmina, while copper from Mpemba was taken to Luanda and further to Calabar and Rio Del Rey.27

While much of this trade was handled by Europeans, a significant proportion was likely undertaken by African merchants, and it’s not implausible that local mariners like the Mpongwe were trading internally along the central African coast, just like the Gold Coast mariners were doing in the Bight of Benin, and that these different groups of sailors and regional systems of trade overlapped.

For example, there is evidence of mariners from Lagos sailing in their vessels westwards as far as Allada during the 18th century where they were regular traders28. These would have met with established mariners like the Itsekiri and immigrants such as those from the Gold Coast. And there's also evidence of mariners from Old Calabar sailing regularly to the island of Fernando Po (Bioko), in a pattern of trade and migration that continued well into the early 20th century. It is therefore not unlikely that this regional maritime system extended further south to connect the Bight of Benin to the Loango Coast.29

Map of the Loango coast in the 17th century, By Alisa LaGamma

Travel and Migration to Central Africa by African mariners: from fishermen to administrators.

There is some early evidence of contacts between the kingdoms of Benin and Kongo in the 16th century, which appear to have been conducted through Sao Tome. In 1499, the Oba of Benin gifted a royal slave to the Kongo chief Dom Francisco. A letter written by the Kongo king Alfonso I complained of people from Cacheu and Benin who were causing trouble in his land. In 1541 came another complaint from Kongo that Benin freemen and slaves were participating in disturbances in Kongo provoked by a Portuguese adventurer. 30

But the more firm evidence comes from the 19th century, during the era of 'legitimate trade' in commodities (palm oil, ivory, rubber) after the ban on slave exports. The steady growth in commodities trade during this period and the introduction of the steamship expanded the need for smaller watercraft (often surfboats) for ship-to-shore supplies and to navigate the surf.

Immigrant mariners from Aneho came to play a crucial role in the regional maritime transport system which developed in parallel to the open sea transport. By the late 19th century, an estimated 10,000 men were involved in this business in the whole of the Bight of Benin as part much broader regional system. Immigrant mariners from Aneho settled at the bustling port towns of Lome and Lagos during the late 19th century and would eventually settle at Pointe-Noire in Congo a few decades later, where a community remains today that maintains contact with their homeland in Ghana and Togo.31

Parallel to these developments was the better-documented expansion of established maritime communities from the Gold Coast, Liberia, and the Bight of Benin, into the Loango coast during the late 19th century, often associated with European trading companies. Many of these were the Kru' of the Liberian coast32, but the bulk of the immigrant mariners came from Aneho and Grand Popo (known locally as 'Popos’), El-Mina (known locally as Elminas), and southwestern Nigeria (mostly from Lagos). A number of them were traders and craftsmen who had been educated in mission schools and were all generally referred to by central Africans as coastmen ("les hommes de la côte").33

Most of these coastmen came with the steamers which frequented the regions’ commodity trading stations, where the West Africans established fishing communities at various settlements in Cabinda, Boma, and Matadi.34 Others were employed locally by concessionary companies and in the nascent colonial administration of French Brazaville35 and Belgian Congo.

One of the most prominent West African coastmen residing in Belgian Congo was the Lagos-born Herzekiah Andrew Shanu (1858-1905) who arrived in Boma in 1884 and soon became a prominent entrepreneur, photographer, and later, administrator. He became active in the anti-Leopold campaign of the Congo Reform movement, providing information about the labour abuses and mass atrocities committed by King Leopold’s regime in Congo. When his activism was discovered, the colonial government banned its employees from doing business with him, which ruined him financially and forced him to take his life in 1905.36

Herzekiah André Shanu (1858-1905) and Gerald Izëdro Marie Samuel (1858-1913). Both were Yoruba speakers from Lagos and they moved to Boma in Congo, during the 1880s, the second photo was taken by Herzekiah.

The immigrants from West Africa who lived in the emerging cities of colonial Congo such as Matadi, Boma, and Leopodville (later Kinshasha) also influenced the region’s cultures. They worked as teachers, dock-hands, and staff of the trading firms that were active in the region. These coastmen also carried with them an array of musical instruments introduced their musical styles, and created the first dance ochestra called 'the excelsior'. Their musical styles were quickly syncretized with local musical traditions such as maringa, eventually producing the iconic musical genres of Congo such as the Rumba.37

While the population of West African expatriates in central Africa declined during the second half of the 20th century, a sizeable community of West Africans remained in Pointe Noire in Congo. The members of this small but successful fishing community procure their watercraft from Ghana and regularly travel back to their hometowns in Benin, just like their ancestors had done centuries prior, only this time, by air rather than by ocean.

Pointe-Noire, Republic of Congo

Did Mansa Musa’s predecessor sail across the Atlantic and reach the Americas before Columbus? Read about Mansa Muhammad's journey across the Atlantic in the 14th century, and an exploration of West Africa's maritime culture on Patreon

Why was the wheel present in some African societies but not others? Read more about the history of the wheel in Africa here:

Map by J.K.Thornton

Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400-1800 by John Thornton pg 17-20

West Africa's Discovery of the Atlantic by Robin Law pg 3, Africa and the Sea by Jeffrey C. Stone pg 79

West Africa's Discovery of the Atlantic by Robin Law pg 4-5)

A Cultural History of the Atlantic World, 1250-1820 By John K. Thornton pg 11-14, Remote Sensing of the African Seas edited by Vittorio Barale, Martin Gade, pg 6-9,

Map by Vittorio Barale and Martin Gade

A Cultural History of the Atlantic World, 1250-1820 By John K. Thornton pg 13

Undercurrents of Power: Aquatic Culture in the African Diaspora by Kevin Dawson pg 101)

Undercurrents of Power: Aquatic Culture in the African Diaspora by Kevin Dawson pg 121-122)

A Cultural History of the Atlantic World, 1250-1820 By John K. Thornton pg 12)

West Africa's Discovery of the Atlantic by Robin Law pg 7, Undercurrents of Power: Aquatic Culture in the African Diaspora by Kevin Dawson 125, Eurafricans in Western Africa By George E. Brooks pg 166

Kongo power and majesty by Alisa LaGamma pg 47-48)

Red Gold of Africa: Copper in Precolonial History and Culture By Eugenia W. Herbert, pg 216, Two Trips to Gorilla Land and the Cataracts of the Congo,: Volume 1 By Sir Richard Francis Burton, pg 83, Precolonial African Material Culture By V Tarikhu Farrar, pg 243

Undercurrents of Power: Aquatic Culture in the African Diaspora by Kevin Dawson pg 126)

Afro-European Trade in the Atlantic World by Silke Strickrodt pg 68, Africans and Europeans in West Africa By Harvey M. Feinberg pg 67)

Undercurrents of Power: Aquatic Culture in the African Diaspora by Kevin Dawson pg 112

Afro-European Trade in the Atlantic World by Silke Strickrodt pg 69)

Undercurrents of Power: Aquatic Culture in the African Diaspora by Kevin Dawson pg 126-127)

Remarks on the Country Extending from Cape Palmas to the River Congo By John Adams pg 243)

Afro-European Trade in the Atlantic World by Silke Strickrodt pg 69-70, Undercurrents of Power: Aquatic Culture in the African Diaspora by Kevin Dawson pg 127)

Afro-European Trade in the Atlantic World by Silke Strickrodt pg 70, Africans and Europeans in West Africa By Harvey M. Feinberg pg 68-70)

Afro-European Trade in the Atlantic World by Silke Strickrodt pg 71, West Africa's Discovery of the Atlantic by Robin Law pg 23)

Afro-European Trade in the Atlantic World by Silke Strickrodt pg 147, 158, Undercurrents of Power: Aquatic Culture in the African Diaspora by Kevin Dawson pg 126)

Afro-European Trade in the Atlantic World by Silke Strickrodt pg 70-74, 78-88, Undercurrents of Power: Aquatic Culture in the African Diaspora by Kevin Dawson pg 132)

Afro-European Trade in the Atlantic World by Silke Strickrodt pg 74)

West Africa's Discovery of the Atlantic by Robin Law pg 6, 7-9)

The External Trade of the Loango Coast and Its Effects on the Vili, 1576-1870 by Phyllis M. Martin (Doctoral Thesis) pg 111-115

Remarks on the Country Extending from Cape Palmas to the River Congo By John Adams, pg 96

Studies in Southern Nigerian History by Boniface I. Obichere pg 209, The Calabar Historical Journal, Volume 3, Issue 1 pg 48-50

Benin and the Europeans, 1485-1897 by Alan Frederick Charles Ryder pg 36, n.1)

Migrant Fishermen in Pointe-Noire by E Jul-Larsen pg 15-16)

Navigating African Maritime History pg 117-138, Travel and Adventures in the Congo Free State pg 44

In and Out of Focus: Images from Central Africa, 1885-1960 by Christraud M. Geary pg 103-104)

Les pêcheries et les poissons du Congo by Alfred Goffin pg 16, 181, 208)

Leisure and Society in Colonial Brazzaville By Phyllis Martin pg 27

In and Out of Focus: Images from Central Africa, 1885-1960 By Christraud M. Geary pg 104-106)

Rumba on the River: A History of the Popular Music of the Two Congos By Gary Stewart, 'Being modern does not mean being western': Congolese Popular Music, 1945 to 2000 by Tom Salter Pg 2-3)