The city states of the Yoruba: a history of pre-colonial West African urbanism (1000-1900 CE)

At the close of the 19th century, the Yorùbá region of South-west Nigeria was one of the most urbanized places in Africa.

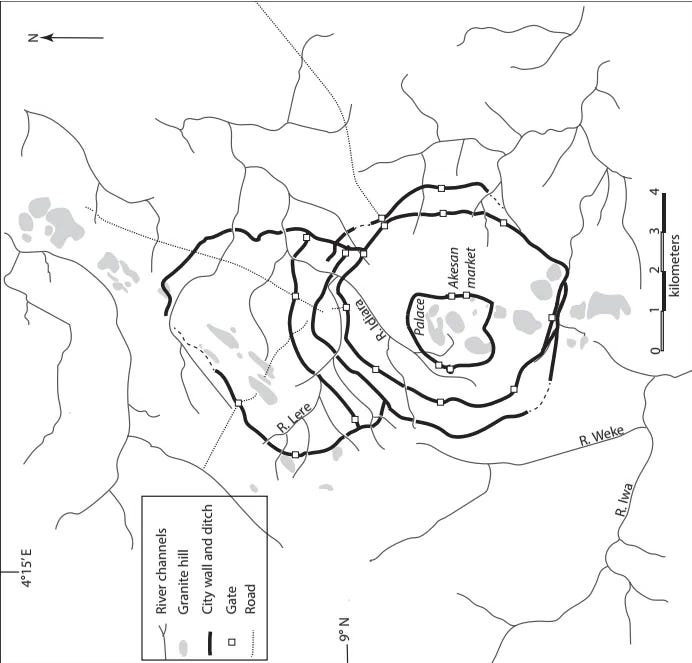

Throughout the region, monumental constructions described as ‘ramparts’ or ‘walls’ extending over 100km with ditches 5 to 20 meters deep, enclosed large cities containing between 40,000 to 100,000 people, ranking them among the largest cities on the continent.

Located between the forest and coastal regions of West Africa, where urbanism was initially thought to have been the product of external stimulus, the discovery of ancient walled cities in Yorubaland provided further evidence for the independent emergence of cities in pre-colonial Africa.

This article outlines the history of the Yorbaland cities, including an overview of their political history and architecture.

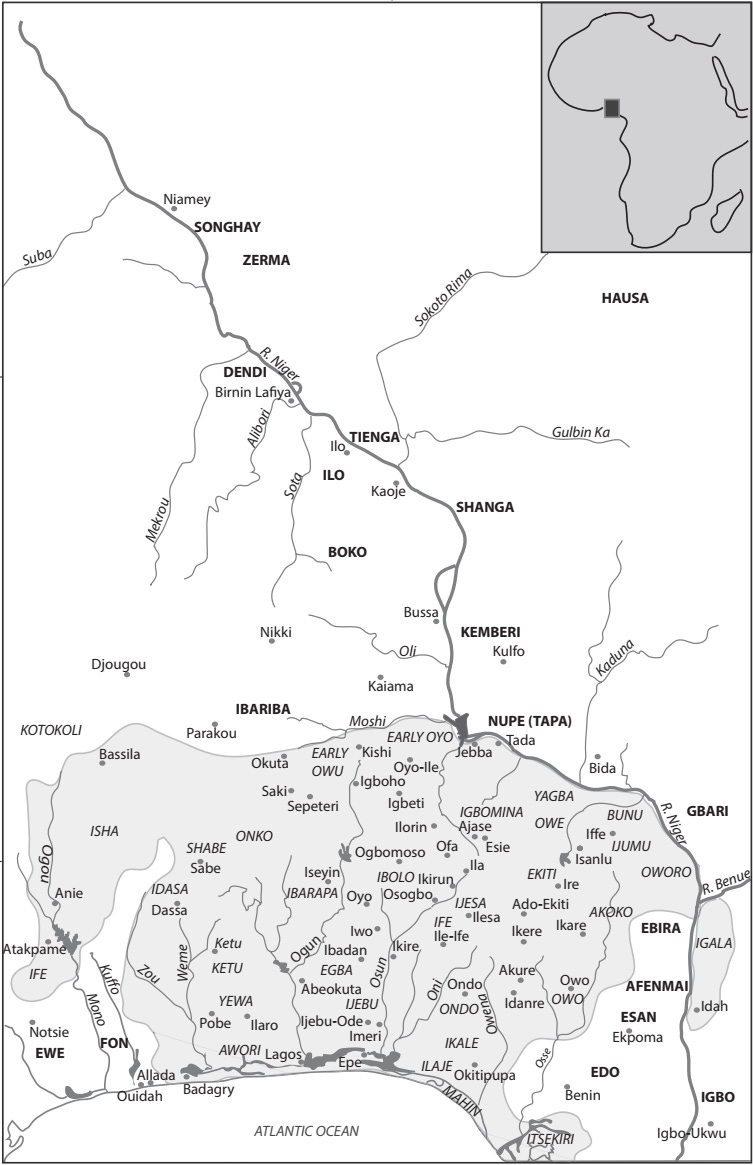

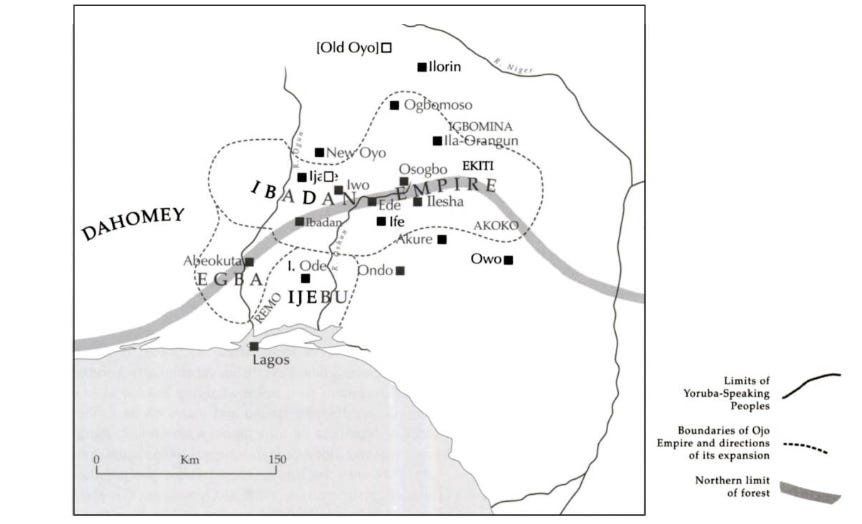

Map of Yorubaland and its cities.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Origins and development of Yoruba cities from the Middle Ages to the 18th century

The Yoruba-speaking world straddles the savannah and forest regions of what is today south-western Nigeria.

Historically, the various polities of the Yoruba-speaking world varied greatly in size and structure, from large empires like Oyo to middle-sized kingdoms like Ile-Ife and Ijebu to smaller kingdoms and confederations like Egba and Ekiti. Archaeological evidence from early earthwork complexes such as Sungbo’s Eredo and the old capitals of Ife and Oyo suggests that urbanization and large political units emerged across the region by the start of the 2nd millennium CE.

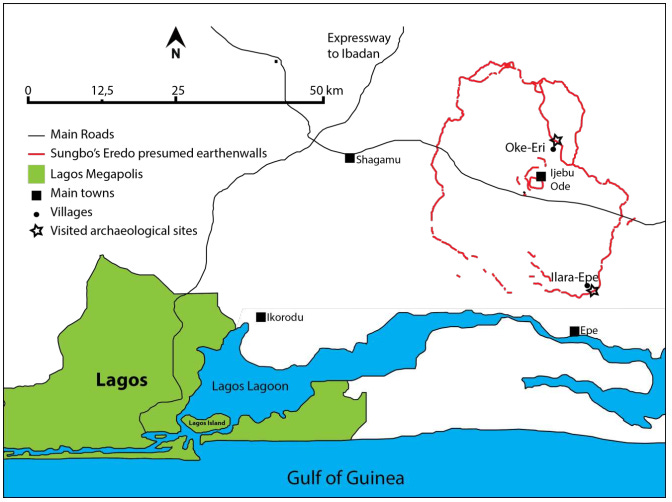

Located a few kilometres north of Lagos, the 20-meter-tall rampart at Sungbo snakes through 185 kilometres of thick rainforest undergrowth, enclosing an area of about 1,025 sq km. Dated material from the site indicates it was first occupied in the 11th-13th century. An inventory of similar enclosures in the region lists at least 21 different sites that were built across Yorubaland during the same period as Sungbo, many of which are abandoned and are today concealed beneath dense vegetation.1

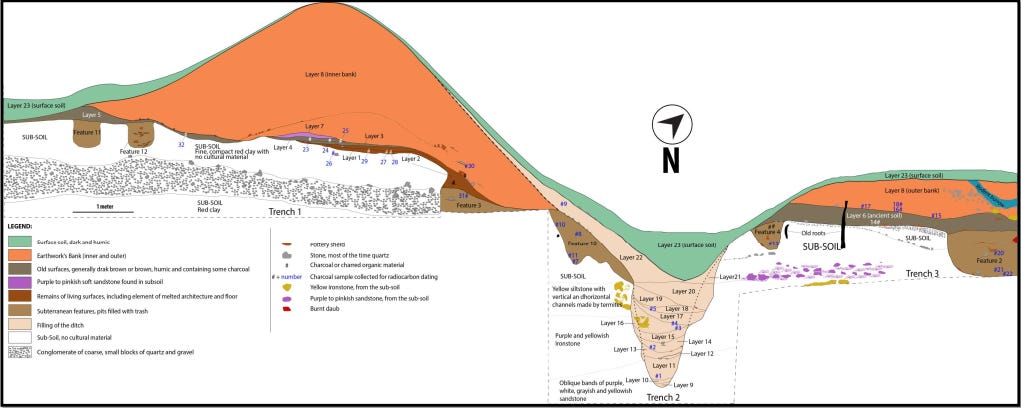

The rampart and ditch system of Sungbo Eredo

Location of Sungbo’s Eredo, south-western Nigeria. Map by Gérard Chouin et al.

The foundational concept of Yoruba political sociology was the term ilu, commonly translated as ‘town’ or ‘community.’ An ilu is an aggregate of corporate descent groups or lineages that has an organised government of king (oba) and chiefs. Like all urban societies, an ‘ilu’ was distinguished from the surrounding rural settlements by its function as the main political, economic, and religious centre. A Yoruba city was thus ‘town’ and ‘polity’ with the latter typically named after the former.2

The most important among the early cities was Ife, where, according to Yoruba traditions, the world was created. Excavations in the modern city produced a radiocarbon chronology suggesting that occupation commenced during the late first millennium CE and reached its peak during the ‘Classical period’ (1000–1500 CE).3

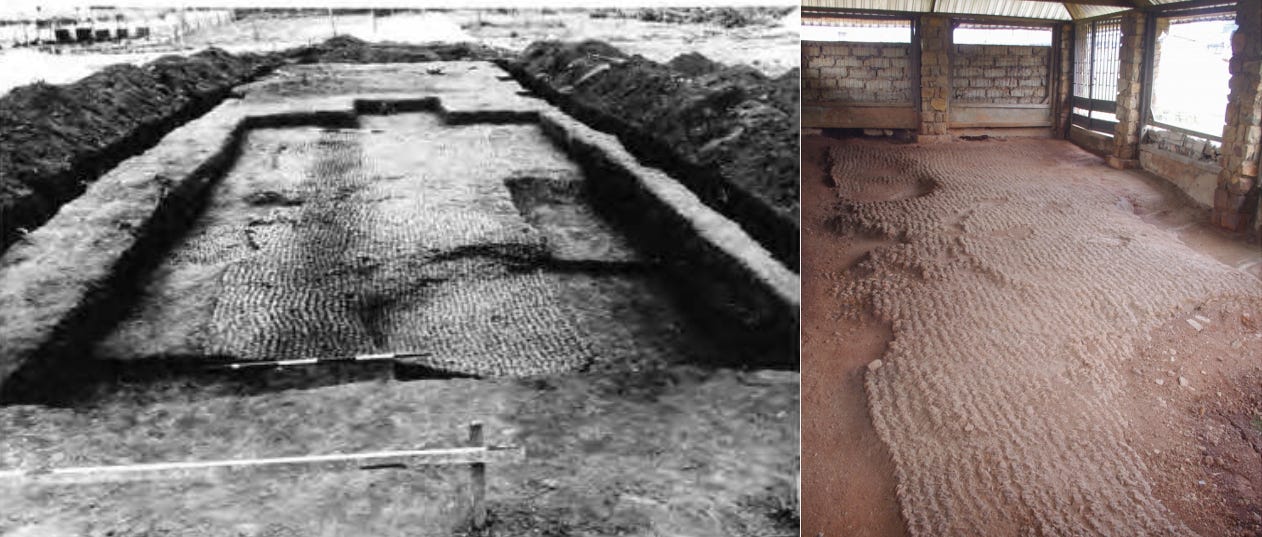

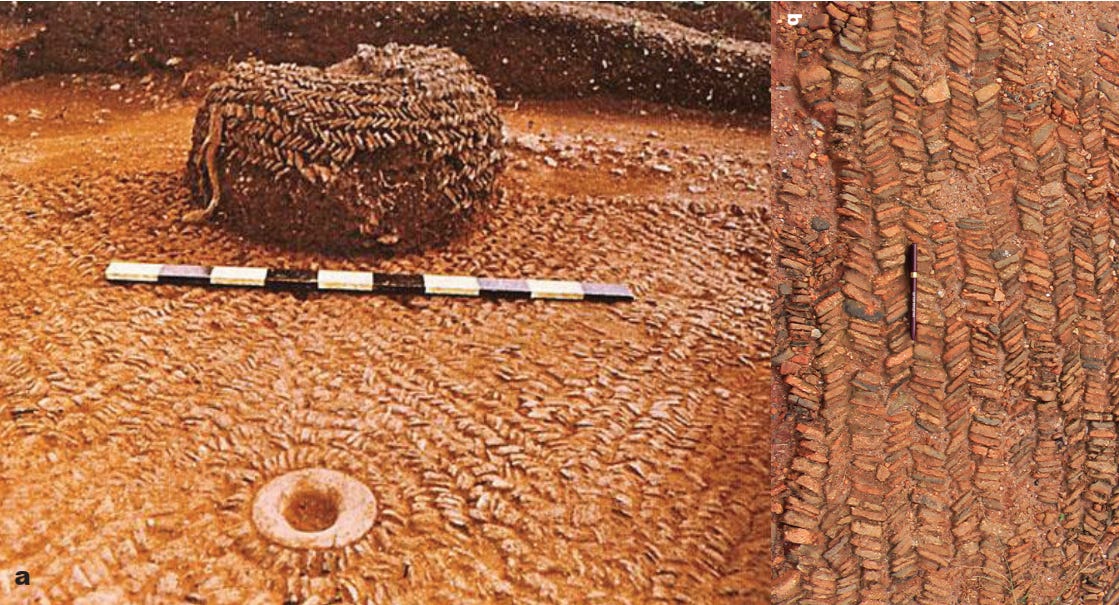

This period marked the city’s transformation into the main political and religious centre of Yorubaland, and the production of its famous sculptural artworks and glass manufacturing. The paving of several streets and the floors of elite houses and religious sites with potsherds and stones was also undertaken during this period, becoming the distinctive material characteristic of Ife’s urban space.

At Ife, fragments of these pavements can still be seen within a radius of 6 km from the town's center. The city was abandoned in the late 14th century, but was later repopulated in the 16th/17th century4

Archaeologists suggest that the medieval city was as large as the 19th-century walled town, because some of the excavated sites lie outside its walls. Describing the medieval city, Garlake observed that ‘There are strong indications that buildings were sufficiently compact and close together for the settlement to be ranked as urban.’ An estimated 70,000–105,000 people were living there at its 14th/15th-century peak.5

(left) Pavement at Ita Yemoo, Ife, measuring 9.4 x 3.7 m from the 1950s excavations. Image from Hunterian Museum and University of Glasgow Archives & Special Collections, Frank Willett collection.6 (Right) Pavement on the site of an ancient sacred place preserved in a space created within the grounds of the National Museum of Ile-Ife. image and caption by Gérard Chouin

Potsherd pavements from (a) Obalara Land and (b) Igbó Olókun. images by Akinwumi Ogundiran

View of the pavements towards the east, Ita Yemoo site, Ife. Image by the Ife-Sungbo Archaeological Mission, 2022.

Another city that emerged during the early 2nd millennium CE was Oyo-ile, which later became the capital of a large kingdom. Radiocarbon dates from the excavations at Old Oyo indicate the existence of a substantial settlement of more than 1 km2 as early as the 12th century. By 1600, it was a major urban centre with multiple defensive walls enclosing a high density of residential structures. At its mid-18th-century peak, as the capital of the Oyo Empire, it covered more than 5000 ha.7

Archaeological surveys revealed five expansive wall systems, covering 50 km2, built over the course of the 16th through the late 18th century. Intrasite spatial analysis of artifact densities suggests that at its peak in the 18th century, the capital probably housed between 60,000 and 140,000 people.8

Perimeter walls of Òyó-Ilé. image by Akinwumi Ogundiran.

The free-standing walls at Koso hill, a capital of Oyo during the reign of Alaafin Sango. The hill settlement is surrounded by three walls, one of which extends south to Oyo-ile. The height of the walls ranges from 5.1m to 7m, and they are about 1.6m thick. There are perhaps the only free-standing walls still preserved in Yorubaland.9

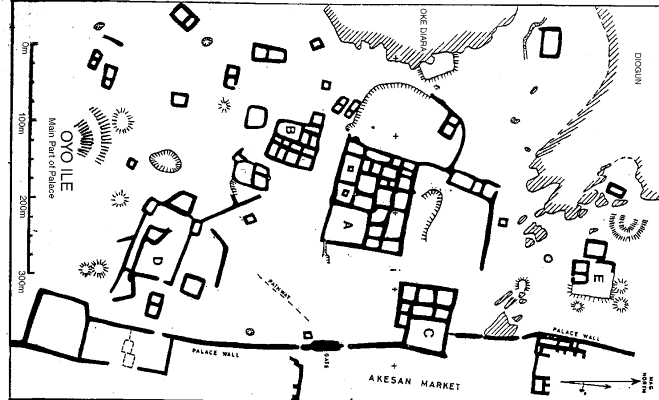

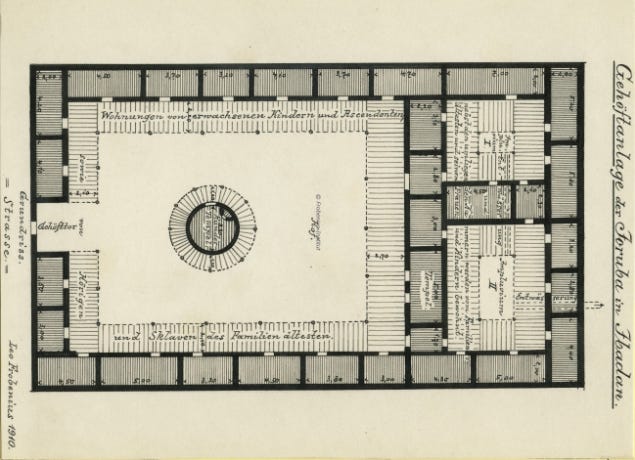

Archaeological surveys of Oyo-Ile and Ile-Ife indicate that the architecture of the older Yoruba cities consisted of large rectilinear earthen structures, most of which left few standing remains. Nevertheless, the material of the solid mud structures formed low banks, which still preserve the ground plans of the buildings, indicating parallel walls of rooms arranged around a courtyard or series of courtyards.

The largest of these structures were found in the palace complex, which was enclosed within a perimeter wall extending over 7.5 km, outside of which was a market and numerous domestic structures within an area measuring about 2,010 ha.10

Evidence from the mosaic terraces found in Ife suggests that compounds where the art was displayed were of the open impluvial-courtyard type. Stone and postsherd mosaic areas distinguish these settings, which sometimes bear semi-circular cutaway areas where earthen altars were constructed for shrine objects and offerings.11

Oyo Ile, Main part of the Palace, illustration by Robert Sopher

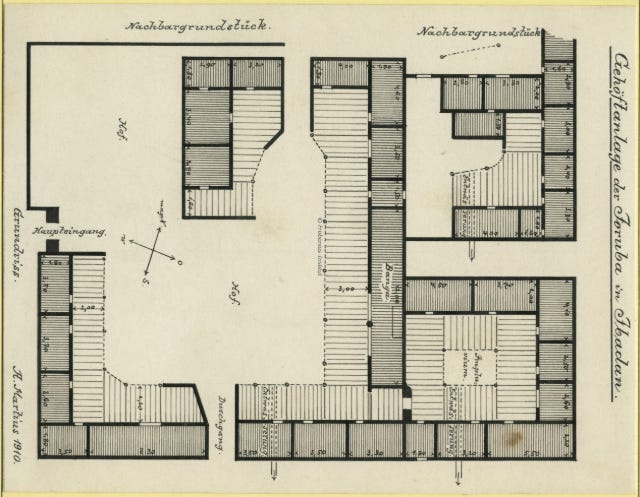

Yoruba impluvium-courtyard house in Ibadan. The smaller courtyards on the right contain the Impluvium I and II, and their surrounding chambers are inhabited by the family elder and his wives and children. The main courtyard contains the round temple at the center, dwellings of adult children and ascendants, as well as serfs and slaves of the family elder, and the gateway into the street. Illustration and captions by Leo Frobenius, ca. 1910-1912

Postherd pavement at Old ile. Image by C.A. Folorunso et al.12

Pavement with cavity at Ita Yemoo, Ife. Image from the Ife-Sungbo Archaeological Mission, 2022

Terracotta altar found by Frank Willett at the Grid site in Ita Yemoo, in association with a paved complex. Image reproduced by Gérard Chouin

Oyo brought many hitherto independent cities under its control through aggressive expansion, which served as a major catalyst for the establishment and/or expansion of cities in Yorubaland. Some of these cities were brought under its orbit, others claimed origins from Ife, while the rest were independent of Oyo.

Among the independent polities to its east was the 16th-century kingdom of Ijesha, whose capital, Ilesha, was one of the largest cities of the period. It measured about 3 km across within its circuit of mud-built walls and ditch, and had a population of about 30-40,000 at its height.

Ilesha lay at the centre of a territory extending outwards some 20-30 km in each direction, and included over 160 subordinate settlements in the mid-19th century. Some of these were previously independent polities, others were founded as out settlements from Ilesha, with farms that supplied the capital.13

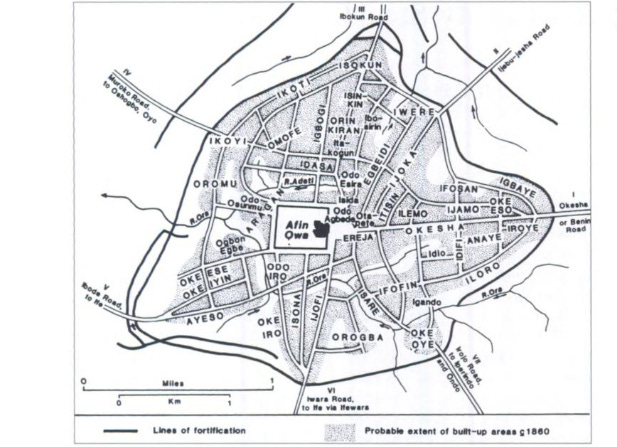

Ilesha preserves the classical layout of the older Yoruba cities. The palace of the Oba (King) was the locus of the town's layout from which the town's roads and streets radiated outwards like spokes of a wheel and continued beyond the town gates to the frontiers of the kingdom. Traditions hold that this layout was modeled on the one found in Oyo-Ile.14

The Ilu of Ilesha, the town and its quarters, Map by J.D.Y. Peel

To the south of Oyo was the city-state of Owu, the Egba polities, and the Ijebu kingdom, whose capital, Ijebu Ode, was located within the earthworks of Sungbo’s Eredo. Ijebu was one of the largest kingdoms after Oyo, and included many subordinate towns. It was also one of the earliest Yoruba kingdoms of which we have contemporary evidence: a 1505 Portuguese account refers to “a very large city called Geebuu, surrounded by a great moat ... [whose] ruler is called Agusale ...”15

However, Ijebu's external contacts and trade with the Portuguese and Dutch remained modest during the 16th and 17th centuries, as the coastal traders mostly concentrated their activities in the kingdom of Benin and later at Lagos. There were thus few contemporary descriptions of interior cities like Owu, which was also defended by a system of fortifications consisting of massive earthen walls about 20ft high.16

Much of the known history of Yorubaland during the 17th and 18th centuries is thus concerned with the expansion of the Oyo empire, which I explored in my previous essay. The city-states on Oyo’s frontier would continue to flourish into the 19th century, when the empire disintegrated, and transformed the pre-existing structure of Yoruba urbanism.

Map showing the extent of the Oyo empire at its height in the late 18th century

Yoruba cities in the 19th century

The gradual collapse of Oyo's hegemony during the 19th century reshaped the political landscape of Yorubaland, marking the beginning of a period of political upheaval as old cities in the north were abandoned while those in the south expanded.

Competition and inter-state wars —initially between Ijebu, Ife, Owu, and Oyo, and later against the Egba— forced many residents of these cities to migrate southwards and establish more fortified settlements. The capital of Oyo-ile had been largely abandoned and had lost its former splendour by the time the Lander brothers visited it in 1830:

“All seems quiet and peaceable in this large, dull city: one cannot help feeling rather melancholy, in wandering through streets almost deserted, and over a vast extent of fertile land, on which there is no human habitation. The walls of the town have been suffered to fall into decay; and are now no better than a heap of dust and ruins.”17

The empire ultimately collapsed after the late 1830s, in the rebellion launched by the city of Ilorin, whose ruler acknowledged the Caliph of Sokoto as his suzerain. As disorder spread and many towns in the northern heartland of the empire were sacked, there was a massive flood of Oyo refugees to the south and east, which increased the populations of existing towns.18

Several cities, such as Old Oyo, Owu, and Iwere, were razed by war. New cities such as Ibadan, New Oyo, and Abeokuta emerged, while others like Ijaye collapsed shortly after founding. Warlords and other powerful figures, fleeing from their own towns, compelled reigning monarchs to make administrative and economic concessions in cities of the interior like Ilorin, Iwo, Ile-Ife, Ogbomosho, Ede, and Osogbo, as well as those near the coast, such as Ijebu-Ode, and Ondo.19

Like their predecessors, Yoruba cities of the 19th century were often surrounded by walls, as described by the Lander brothers, who crossed Yorubaland in 1830:

“We then crossed a small stream and entered a town of prodigious extent called Bohoo. Its immense triple wall is little short of twenty miles in circuit; but besides huts and gardens, it encloses a vast number of acres of excellent meadow land.”20

Exavations at Ife indicate that the city walls/earthworks which enclose the old city were constructed during the mid-19th century, rather than the medieval period, confirming oral traditions that attribute these constructions to the reign of Ooni Abeweila in 1848/9. These earthworks consisted of an inner bank-and-ditch system approximately 7 km in circumference, surrounded by an outer ditch of 16 km, and covering more than 200 km2.21

Profile of the earthwork at Oke-Atan I, Ile-Ife, Osun State. Profile by Gérard Chouin

View of the entire profile of the Oke-Atan earthwork. image by Gérard Chouin

At New Oyo, a scion of the old dynasty tried to recreate the old imperial capital, but it never attained anything like the size or power of its predecessor. The political successor of Oyo-ile instead developed around Ibadan, which was founded in the 1830s on the site of a former Egba town by a mixed force of Oyo, Ife, Ijebu, and Egba warriors, among whom the Oyos soon became predominant.22

Ibadan evolved as a military republic, with alternating periods of collective leadership and rule by powerful warlords with large followers and supplies of firearms. Its principal warlords evolved a system of ranked military titles, and worked by promotion from lower to higher grades as vacancies occurred. Ibadan subsumed about a third of Yoruba-land, becoming the suzerain of many cities and towns, including new capitals like Ijaye, which was razed in 1862, and old cities like Ilesha, which was sacked and made a tributary in 1870.23

Yorubaland in the late nineteenth century (ca. 1875). Map by J.D.Y. Peel.

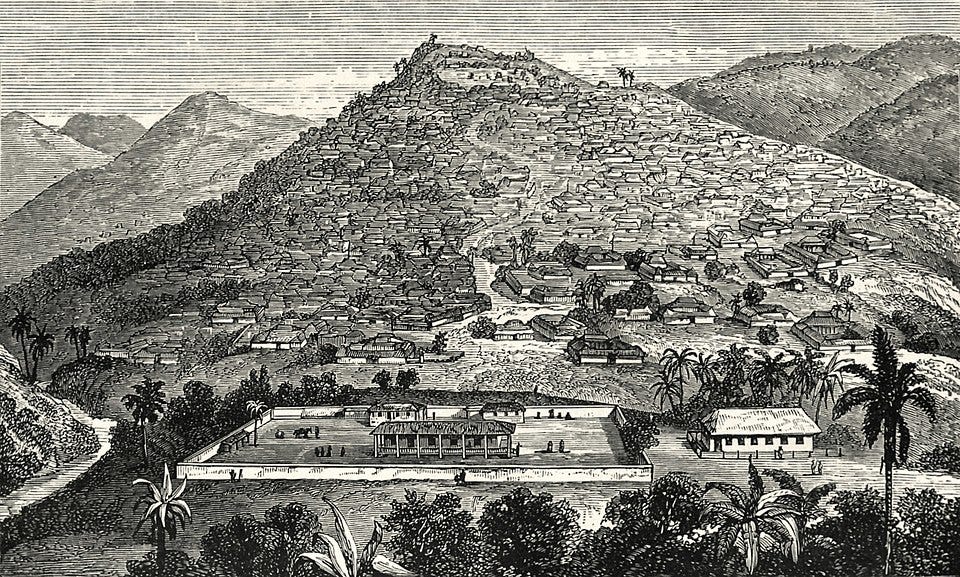

Engraving depicting Ibadan in 1854 by Anna Hinderer

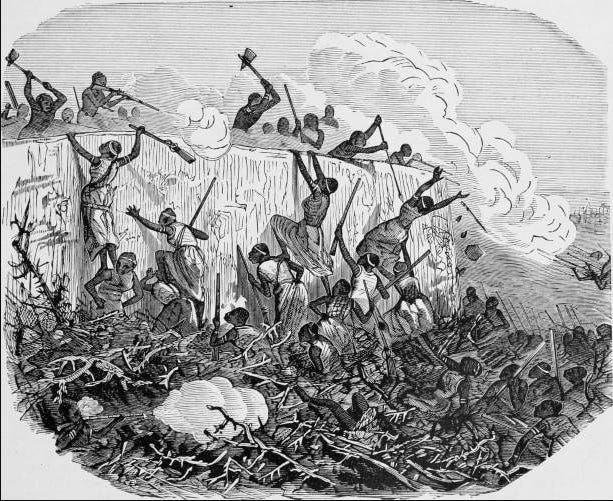

In 1830, groups of Egba refugees established the city of Abeokuta (“Under the rock”) on the western fringe of their former territory. The founding groups kept their internal organization as “townships” within the new unified capital, which by the 1850s was estimated to have a population of 60,000. The city developed a fairly effective military organization, with pan-Egba titles, enabling Abeokuta to beat off the resurgent Dahomey (which had also thrown off Oyo’s suzerainity) and to bring into its orbit many smaller towns to its west and south.24

Abeokuta had four rulers, one for each of the Egba sections, and one for the Owu refugees who later joined them. Threatened by Ibadan to the north and a resurgent Dahomey to the west, Abeokuta soon became embroiled in a regional conflict pitting it and an exiled ruler of Lagos against Dahomey. The former party, with the assistance of the British, successfully repelled an invasion from Dahomey in 1851 and brought Lagos under Abeokuta's orbit.25

Abeokuta, ca. 1897.

Illustration of the 1851 Battle of Abeokuta, during which Dahomey invaders attacked the Egbas’ capital of Abeokuta, in southwest Nigeria, the Egbas, occupying higher ground, use hatchets, spears, and British firearms to fend off Dahomey forces who climb the embankment. ca. 1877, GettyImages

Structure of Yoruba cities during the 19th century.

According to the anthropologist Jeremy Eades, “Yoruba urbanism only assumed its characteristic form as a result of the 19th-century wars, and it was these historical factors which have produced the diversity of settlement patterns.”26

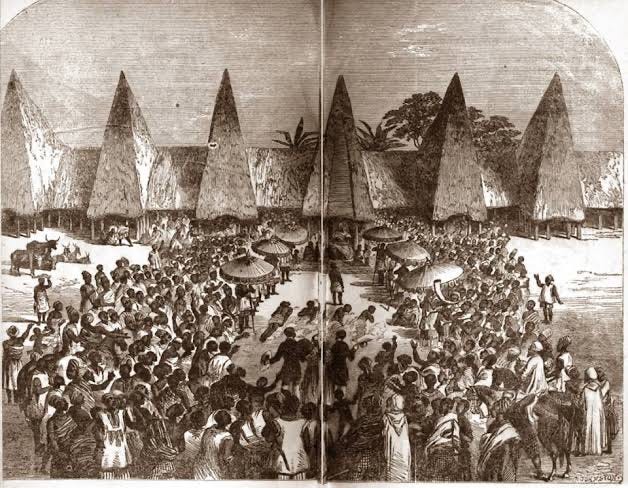

In the 19th century, the institution of kingship retained its importance in the city-state culture of the Yoruba. The oba was elected from one of the segments of a vast royal lineage —typically the largest in the town— by the senior non-royal chiefs acting as “kingmakers”.

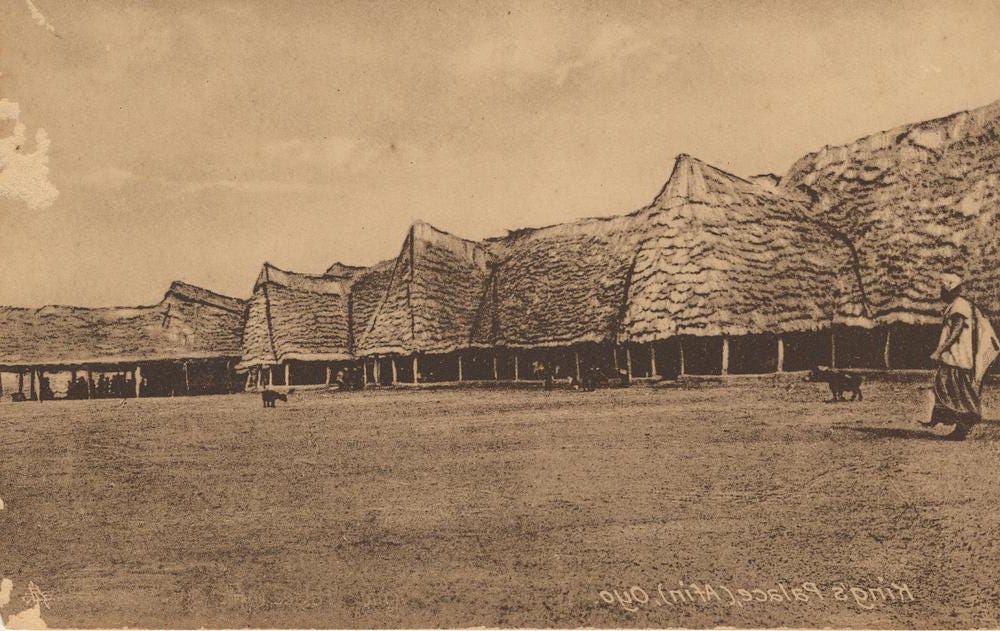

The oba's palace remained the focus of the town’s layout. These palaces were large, sprawling structures, consisting of a complex of buildings, courtyards, public rooms, shrines, and private apartments. In the 1930s, the palace of the Alafin at New Oyo consisted of thirty courtyards, spread over 17 acres, while its predecessor at Oyo-Ile may have extended over an area of a square mile.

The palace of a substantial kingdom was inhabited by the royal wives, functionaries, eunuchs, messengers, priests, clients, slaves, and other dependents. Close by were the compounds of priests and craftsmen ministering to the palace’s needs, and of many of the principal title-holders.27

Alaafin's palace at new-Oyo, 1911, British Museum.

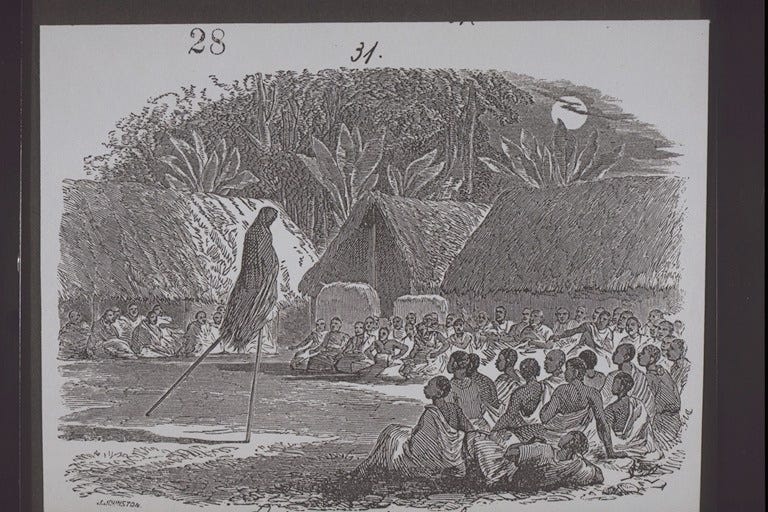

"electing a king in Yoruba" ca. 1856 in Oyo, Nigeria.

The remainder of the city was divided for administrative purposes into a number of wards, known variously as adugbo (Oyo and Ife), itun (Ijebu), and idimi (Ondo), each under the jurisdiction of one of the title-holders. In towns such as Ife and Ilesha, the wards extend out from the centre of the town, clustered around the main roads.

Extending beyond these are the farms belonging to the descent groups within the ward. Each title-holder had to guarantee the loyalty of his following - the members of his lineage, quarter, cult-group, etc., as well as his own household and clients through effective representation of them at the centre, and redistribution to them from it.28

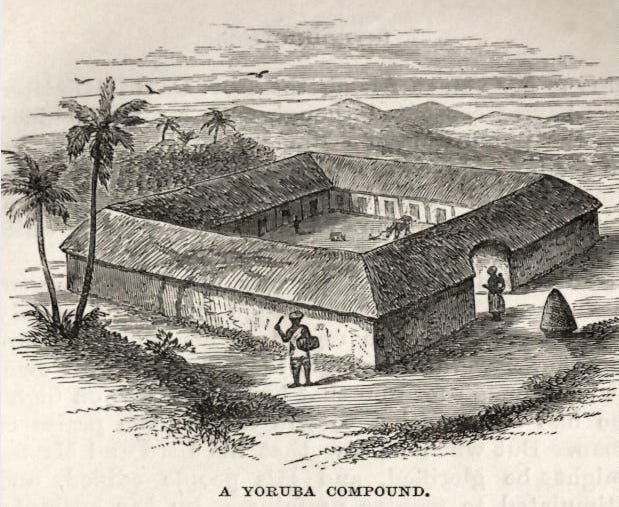

The wards of the town are subdivided into compounds, which are in turn divided into separate houses. In the northern cities, the compounds consisted of several buildings which shared a perimeter wall, or were laid out in a more regular grid pattern with the houses separated by alleyways, as was the case for the southern cities like Ijebu Ode.29

The missionary, Dr. Irving, who visited Ijebu country in 1854-1855, left brief descriptions of its commercial links to Abeokuta and the architecture of its walled towns: Ijebu-Ode and Iperu

“To the right of the gate, and at some little distance behind, arose a two-storied square, vermilion coloured tower, thatched, and loopholed for musketry, passing through which we skirted the town. Every house seemed to have its banana enclosure or grove. The houses were much better built than those of either Abbeoukuta or Ibadan; the walls higher, supported outside by buttresses.”

“Stretching across the end of an avenue was a wall and thatched gate, with neat door, and on either hand a high square tower of defense, similar to the others and in good repair. We were very much pleased with the neatness of the town. The walls of the houses were high, smooth, and buttressed; there appeared to be, in some cases, regular streets... its general cleanness, the neat, well-built houses, and clear open spaces, and the general appearance, had a very good general effect. It was here where the Egbas come from Abbeokuta to trade.”30

In Ibadan, the people settled as clients or followers of warriors (baba-ogun) or in small groups of kin and dependants. The compounds in which they were settled were clusters of buildings with a single gated entrance leading to a large courtyard. There was no system of administrative quarters as in other older Yoruba cities, and the city’s districts were often named after a notable chief or early resident. 31

Despite the political competition and upheavals of the period, trade between the various cities expanded throughout the 19th century.

The cities of Ijebu and Abeokuta in particular became important hubs in the commodities trade with southern coastal entrepots like Lagos and Badagry, and northern markets like Ilorin. Traveling along the navigable Niger in large canoes, they exported locally produced dyed cloths, tools, palm oil, and ivory in exchange for various imports using cowrie shells as currency. 32

Backstreet section in Ilorin, showing a Yoruba man dyeing cotton in indigo surrounded by a large number of large pottery containers, and single-storey thatched-roof buildings in the background. ca. 1946. British Museum

‘A Yoruba Compound’, engraving by Anna Hinderer at Ibadan, ca. 1855

Floor plan of a Yoruba homestead in Ibadan, Illustration by Leo Frobenius, ca. 1910-1912

"Jebu sports - Dancing on stilts" engraving by Dr Irving, ca. 1855. (see my previous essay on ‘A history of Yoruba intellectual culture ca. 1000-1900 AD’)

Estimates from 19th-century accounts suggest that out of the thirty-six main cities, at least six (Ibadan, Ilorin, Iwo, Abeokuta, Oshogbo, and Ede) had more than 40,000 inhabitants; six had 10-20,000; five had 5-10,000; and another five had 1-5,000. There are also occasional references to figures as high as 100,000 for Ibadan, Abeokuta, and Ilorin during the 19th century, reflecting their status as the main centers of political power.33

After its conquest of Ijaye in 1862, Ibadan became the dominant Yoruba power in the interior, which compelled Abeokuta and Ijebu into an alliance of convenience against it and halted its expansion south. While its northern expansion was impeded by Ilorin, its campaigns to the east fared better. Ibadan's armies sacked Ife in 1859, Ijaye in 1862, and Ilesha in 1870, forcing their rulers to pay tribute and bringing more towns under its control.

The British, who had annexed Lagos in 1861, had gradually begun intervening in the regional competition between the three main states, including against former allies like Abeokuta, much to the jeopardy of Christian missions in the interior. Lagos also became the staging point of resistance groups opposed to Ibadan, such as the Etikiparapo, which was led by the Etiki and Ijesha.

This resistance forced Ibadan into a stalemate, which would remain until the British invasion of Yorubaland in the 1890s and the region's annexation into the colony of Lagos, which later became part of Nigeria.34

In the colonial period, many of these cities continued to expand, and some became more cosmopolitan, with a heterogeneous population drawn from across West Africa and the Atlantic world. Today, cities like Ibadan, Lagos, and Abeokuta remain some of the largest urban settlements on the continent.

The Shitta-Bey Mosque in Lagos, an Afro-Brazilian style structure built in 1892 by businessman Mohammed Shitta Bey, who was the son of Sierra Leonean parents of Yoruba descent. British Museum. (see my previous essay on ‘Contributions of Liberated Africans to the economic and cultural growth of 19th century west Africa’)

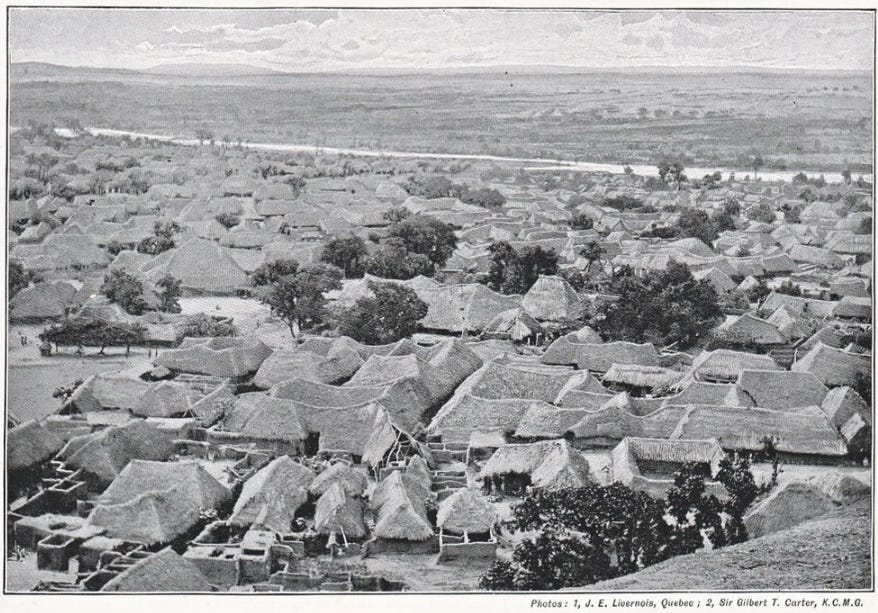

Ibadan in the early 20th century

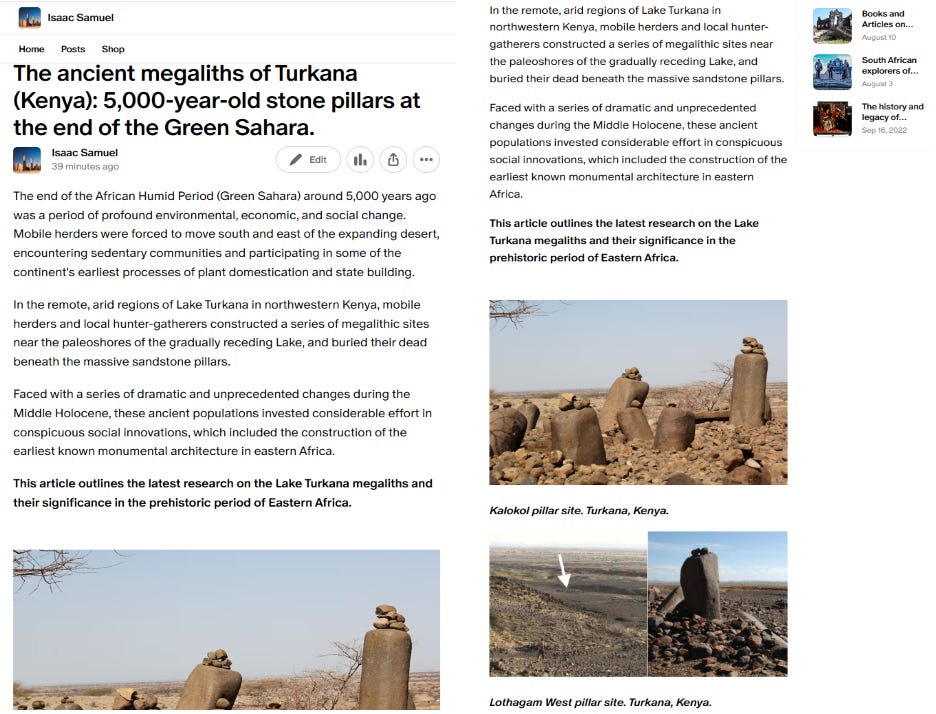

In the Lake Turkana basin of northwestern Kenya, half a dozen megalithic sites were constructed around 5000-4000 years ago at the end of the African Humid period.

My latest Patreon article outlines the latest discoveries on the Lake Turkana megaliths, the functions of the structures, and their significance in the prehistoric period of Eastern Africa.

Sungbo's Eredo, Southern Nigeria, Fossés, enceintes et peste noire en Afrique de l’Ouest forestière (500-1500 AD) Réflexions sous canopée by Gérard L. F. Chouin pg 43-66, for similar ramparts in Igbomina see: On the frontier of empire: understanding the enclosed walls in Northern Yoruba, Nigeria by Aribidesi A. Usman

Religious Encounter and the Making of the Yoruba by J.D.Y. Peel, pg 30-31, Hegemony and Culture: Politics and Religious Change Among the Yoruba by David D. Laitin pg 109-110

African Civilizations: An Archaeological Perspective By Graham Connah, 3rd edition, pg 198

Mission Archeologique Ife-Sungbo, 2018-2022. Rapport Quadriennal. by Gérard Chouin and Adisa Ogunfolakan, et al, 2018 Ife-Sungbo Archaeological Project - Rapport Quadriennal 2015-2018 By Gérard L. F. Chouinn. Classic Ilé-Ifẹ̀ A Consideration of Scale in the Archaeology of Early Yorùbá Urbanism, ad 1000–1400 by Akinwumi Ogundiran

African Civilizations: An Archaeological Perspective By Graham Connah, 3rd edition, pg 198, The Oxford Handbook of African Archaeology edited by Peter Mitchell, Paul Lane pg 863)

Lost in Space? Reconstructing Frank Willett’s excavations at Ita Yemoo, Ile-Ife, Nigeria: Rescue Excavations (1957–1958) and Trench XIV (1962–1963) by Léa Roth, Gérard Chouin and Adisa Ogunfolakan

The Oxford Handbook of African Archaeology edited by Peter Mitchell, Paul Lane pg 866

‘‘Elephants for Want of Towns’’: Archaeological Perspectives on West African Cities and Their Hinterlands by J. Cameron Monroe pg 31-32)

African Indigenous Knowledge and the Sciences: Journeys Into the Past and Present by Gloria T. Emeagwali, Edward Shizha pg 145-165

Museums & Urban Culture in West Africa edited by Alexis Adandé, E. N. Arinze Pg 58-60)

Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba: Ife History, Power, and Identity, c. 1300 By Suzanne Preston Blier pg 131

Revisiting old Oyo: Report on an interdisciplinary field study by C.A. Folorunso, P.A. Oyelaran, B.J. Tubosun, and P.G. Ajekigbe

Yoruba as a City-State Culture by J.D.Y. Peel, pg 507-508

Religious Encounter and the Making of the Yoruba by J.D.Y. Peel, pg 31

Yoruba as a City-State Culture by J.D.Y. Peel, pg 511

Kingdoms of the Yoruba By Robert Sydney Smith pg 63-70

Religious Encounter and the Making of the Yoruba by J.D.Y. Peel, pg 34, The Niger Journal of Richard and John Lander edited by Robin Hallett, pg 86-87

Yoruba as a City-State Culture by J.D.Y. Peel, pg 513

for a general overview of this period, see: War and Peace in Yorubaland, 1793-1893 by I. A. Akinjogbin

The Niger Journal of Richard and John Lander, edited by Robin Hallett, pg 78

Ife-Sungbo Archaeological Project - Rapport Quadriennal 2015-2018 By Gérard L. F. Chouinn. Ife-Sungbo Archaeological Project, preliminary report of 2015 By Gérard L. F. Chouinn and Adisa Ogunfolakan pg 16-18.

Yoruba as a City-State Culture by J.D.Y. Peel, pg 513

Religious Encounter and the Making of the Yoruba By John David Yeadon Peel pg 36-37. for a general overview of Ibadan’s political institutions during this period, see The Balogun in Yoruba land: The Changing Fortunes of a Military Institution by Oluwasegun Mufutau Jimoh

Yoruba as a City-State Culture by J.D.Y. Peel, pg 512

Religious Encounter and the Making of the Yoruba By John David Yeadon Peel pg 38

The Yoruba Today By Jeremy Seymour Eades pg 38

The Yoruba Today By Jeremy Seymour Eades pg 39

Yoruba as a City-State Culture by J.D.Y. Peel, 516, The Yoruba Today by Jeremy Seymour Eades, pg 39

The Yoruba Today By Jeremy Seymour Eades pg 39

Church missionary intelligencer, Volumes 7-8, 1856, Oxford University, pg 117-118

The city of Ibadan by P. C. Lloyd

The City Is Our Farm By Daniel R. Aronson pg 5-6, Slavery and the Birth of an African City: Lagos, 1760--1900 By Kristin Mann pg 136-156

The History of African Cities South of the Sahara: From the Origins to Colonization by Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch 246, 252-253, Iwo: A reevaluation of refugee integration, intergroup relations, and the scenography of power in a 19th-century Yoruba city Akanmu G. Adebayo

Kingdoms of the Yoruba By Robert Sydney Smith, Slavery and the Birth of an African City: Lagos, 1760--1900 By Kristin Mann

Africa's secret golden age!

this is beautiful!