The colonial myth of 'Sub-Saharan Africa' in medieval Islamic geography: the view from Egypt and Bornu.

.

Few intellectual figures of the Muslim world were as prolific as the 15th-century Egyptian scholar Jalal al-Suyuti. A polymath with nearly a thousand books to his name and a larger-than-life personality who once claimed to be the most important scholar of his century, Jalal al-Suyuti is considered the most controversial figure of his time.1

One of the more remarkable events in al-Suyuti's life was when he acted as an intermediary between the ruler of the west-African kingdom of Bornu, and the Abbasid caliph Al-Mutawakkil II —an important figure descended from the Abbasid rulers whose empire fell in 1258 , but was reconstituted at Cairo without their temporal power.

Recounting his encounter with the ruler of Bornu, al-Suyuti writes that;

"In the year 889 [1484 A.D], the pilgrim caravan of Takrur [west-Africa] arrived, and in it were the sultan, the qadi, and a group of students. The sultan of Takrur asked me to speak to the Commander of the Faithful [Al-Mutawakkil] about his delegating to him authority over the affairs of his country so that his rule would be legitimate according to the Holy Law. I sent to the Commander of the Faithful about this, and he did it."2

The Bornu sultan accompanying these pilgrims was Ali Dunama (r. 1465-1497), his kingdom controlled a broad swathe of territory stretching from southern Libya to northern Nigeria and central Chad. Bornu's rulers and students had been traveling to Egypt since the 11th century in the context of the annual pilgrimage to Mecca, making stopovers at Cairo's institutions to teach and study. Their numbers had grown so large that by 1242, they had built a school in Cairo and were regularly attending the college of al-Azhar.3

Al-Azhar hosted students from many nationalities, each of whom lived in their own hostel headed by a teacher chosen from their community, who was in turn under a rector of the college with the title of Shaykh al-Azhar.

In 1834, the shaykh al-Azhar was Hasan al-Quwaysini, an influential Egyptian scholar whose students included Mustafa al-Bulaqi, the latter of whom was a prominent jurist and teacher at the college. Through his contacts with Bornu’s students, al-Quwaysini acquired a didactic work of legal theory written by the 17th-century Bornu scholar Muhammad al-Barnawi and was so impressed by the text that he copied it and asked al-Bulaqi to write a commentary on it. Mustafa's commentary circulated in al-Azhar's scholarly community and was later taken to Bornu in a cyclic exchange that characterized the intellectual links between Egypt and Bornu.

'Shurb al-zulal' (Drinking pure water) by Muhammad al-Barnawi, ca. 1689-1707.4

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

There's no misconception more persistent in discourses about Africa's past than the historicity of the term sub-Saharan Africa; a geo-political term which ostensibly separates the African regions bordering the Mediterranean from the rest of the continent. Many proponents of the term's usage claim that it is derived from a historical reality, in which the ruling Arab elite of the southern Mediterranean created geographic terms separating the African territories they ruled from those outside their control.

They also claim that the 'racial' and 'civilizational' connotations that this separation carries were reflected in the nature of the interaction between the two regions, purporting a unidirectional exchange in which cultural innovations only flowed southwards from "North" Africa but never in reverse. However, a closer analysis of the dynamic nature of exchanges between Egypt and Bornu shows that the separation of "North Africa" from 'Sub-Saharan' Africa was never a historical reality for the people living in either region, but is instead a more recent colonial construct with a fabricated history.

Sketch of the Bornu Empire

About a century before al-Suyuti had brokered a meeting between the Bornu sultan and the Abbassid Caliph, an important diplomatic mission sent by the Sultan of Bornu ʿUthmān bin Idrīs to the Mamluk sultan al-Ẓāhir Barqūq had arrived in Cairo in 1391. The Bornu ambassador carried a letter written by their sultan's secretary as well as a 'fine' gift for the Mamluk sultan according to the court historian and encyclopedist al-Qalqashandī (d. 1418).

The letter related a time of troubles in Bornu when its rulers were expelled from its eastern province of Kanem after a bitter succession crisis. In it, the Bornu sultan mentions that a group of wayward tribes of “pagan” Arabs called the judham, who roamed the region between Egypt and Bornu had taken advantage of the internal conflict to attack the kingdom. He thus requested that the Mamluk sultan, whom he accords the title of Malik (king), should "restrain the Arabs from their debauchery" and release any Bornu Muslims in his territory who had been illegally captured in the wars.5

In their response to the Bornu sultan, the titles used by the Mamluk chancery indicated that the Bornu sultan, whom they also referred to as Malik, was as highly regarded as the sultanates of Morocco, Tlemcen or Ifrīqiya and deserved the same etiquette as them. This remarkable diplomatic exchange between Bornu and Mamluk Egypt, in which both rulers thought of each other as equal in rank and their subjects as pious Muslims, underscores the level of cultural proximity between Egyptian and Bornuan society in the Middle Ages.6

Bornu eventually restored its authority over much of Kanem, pacified the wayward Arabs who were reduced to tributary status, and established its new capital at Ngazargamu which had become a major center of scholarship by the time its sultan Ali Dunama met Al-Suyuti in 1484. The Egyptian scholar mentions that the pilgrims who accompanied Sultan Ali Dunama included a qadi (judge) and "a group of students" who took with them a collection of more than twenty of al-Suyuti's works to study in Bornu.7

Al-Suyuti also mentions that he brokered another meeting between the Abbasid Caliph and another sultan of Takrur; identified as the Askiya Muhammad of Songhai (r. 1493-1528), when the latter came to Cairo on pilgrimage in 1498. Al-Suyuti was thus the most prominent Egyptian scholar among West African scholars, especially regarding the subject of theology and tafsīr studies (Quranic commentary). His influence is attested in some of the old Quranic manuscripts found in Bornu, which explicitly quote his works.8

undated Borno Qur’an page showing the commentary on Q. 2:34 (lines 8–10) which was taken from Tafsīr al-Jalālayn of al-Suyuti. (translation and image by Dmitry Bondarev), SOAS University of London

The vibrant intellectual traditions of Bornu were therefore an important way through which its society was linked to Mamluk Egypt and the rest of the Islamic world, both politically and geographically.

Works on geography by Muslim cartographers such as the Nuzhat of al-Idrisi (d. 1165) and the Kharīdat of Ibn al-Wardī (d. 1349) were available in Bornu where its ruler Muhammad al-Kanemi (r.1809-1837) showed a map to his European guest that was described by the latter as a “map of the world according to Arab nations”. Such geographic works were also available in Bornu’s southwestern neighbor; the empire of Sokoto, where they were utilized by the 19th-century scholar Dan Tafa for his work on world geography titled ‘Qataif al-jinan’ (The Fruits of the Heart in Reflection about the Sudanese Earth (world)".9

Both Dan Tafa and the classical Muslim geographers defined different parts of the African continent and the people living in them using distinct regional terms. The term Ifriqiyya —from which the modern name of the continent of Africa is derived— was only used to refer to the coastal region that includes parts of Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya, which used to be the Roman province of Africa. The term Maghreb (West) was used to refer to the region extending from Ifriqiyya to Morocco. The region below the Maghreb was known as "Bilad al-Sudan" (land of the blacks), extending from the kingdom of Takrur in modern Senegal to the kingdom of Kanem [Bornu].10

Providing additional commentary on the origin of the term Bilad al-Sudan, Dan Tafa writes that "Sudan means the southern regions of the earth and the word is the plural for ‘black’ stemming from the ‘blackness’ of their majority.”11

The term 'Sudan' is indeed derived from the Arabic word for the color 'black'. Its singular masculine form is Aswad and its feminine form is Sawda; for example, the black stone of Mecca is called the 'al-Ḥajaru al-Aswad'. However, the use of the term Sudan in reference to the geographic regions and the people living there wasn't consonant with 'black' (or 'Negro') as the latter terms are used in modern Europe and America.

Some early Muslim writers such as the prolific Afro-Arab writer Al-Jahiz (d. 869) in his work ‘Fakhr al-Sudan 'ala al-Bidan’ (The Boasts of the Dark-Skinned Ones Over The Light-Skinned Ones) utilised the term 'Sudan' as a broad term for many African and Arab peoples, as well as Coptic Egyptians, Indians, and Chinese.12 However, the context in which al-Jahiz was writing his work, which was marked by intense competition and intellectual rivalry between poets and satirists in the Abbasid capital Bagdad13, likely prompted his rather liberal use of the term Sudan for all of Africa and most parts of Asia.

A similarly broad usage of the term Sudan can be found in the writings of Ibn Qutayba (d. 889) whose account of the ancient myth of Noah’s sons populating the earth, considered Ham to be the father of Kush who in turn produced the peoples of the ‘Sudan’; that he lists as the ‘Nuba’, Zanj, Zaghawa, Habasha, the Egyptian Copts and the Berbers.14 which again, don’t fit the Euro-American racial concept of ‘Black’.

On the other hand, virtually all of the Muslim Geographers restricted their use of 'Bilad al-Sudan' to the region of modern West Africa extending from Senegal to the Lake Chad Basin, and employed different terms for the rest of Africa. Unlike the abovementioned writers, these Geographer’s use of specific toponyms and ethnonyms could be pinpointed to an exact location on a map. It was their choice of geographic terms that would influence knowledge of the African continent among later Muslim scholars.

The middle Nile valley region was referred to as Bilad al-Nuba (land of the Nubians) in modern Sudan. The region east of Nubia was referred to as "Bilad al-Habasha" (land of the Habasha/Abyssinians) in modern Ethiopia and Eritrea, while the east African coast was referred to as "Bilad al-Zanj" (land of the Zanj). The region/people between al-Sudan and al-Nuba were called Zaghawa, and between al-Nuba and al-Habasha were called Buja. On the other hand, the peoples living between al-Habasha and al-Zanj were called Barbar, the same as the peoples who lived between the Magreb and Bilad al-Sudan.15

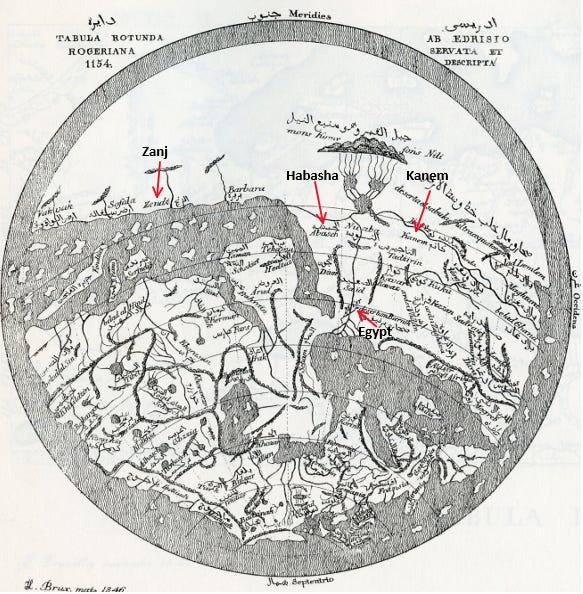

A simplified copy of Al-Idrisi’s map made by Ottoman scholar Ali ibn Hasan al-Ajami in 1469, from the so-called “Istanbul Manuscript”, a copy of the Book of Roger.

A redrawing of al-Idrisi’s map of the world by German cartographer Konrad Miller in 1923, is considered more accurate than the more simplified Ottoman map above.

*both maps are originally oriented south but the images here are turned to face north*

These terms were utilized by all three geographers mentioned above to refer to the different regions of the African continent known to Muslim writers at the time. Most of the names for these regions were derived from pre-existing geographic terms, such as the classical terms for Nubia and Habasha which appear in ancient Egyptian and Nubian documents16, as well as the term 'Zanj' that appears in Roman and Persian works with various spellings that are cognate with the Swahili word ‘Unguja’, still used for the Zanzibar Island.17

While Muslim geographers made use of pre-existing Greco-Roman knowledge, such as al-Idrisi’s reference to Ptolemy’s Geographia in the introduction to his written geography, the majority of their information was derived from contemporary sources. The old greco-roman terms such as ‘aethiopians’ of Africa that were vaguely defined and located anywhere between Morocco, Libya, Sudan, and Ethiopia, were discarded for more precise terms based on the most current information by travelers.18 But their information was understandably limited, as they thought the Nile and Niger Rivers were connected; believing that the regions south of the Niger River were uninhabited, and that all three continents were surrounded by a vast ocean.19

There was therefore no broad term for the entire African continent in the geographic works of Egypt and the rest of the Muslim world, nor was there a collective term for “black” Africans. The Arab sociologist Ibn Khaldun (d. 1406) who lived most of his later life in Cairo, was careful to caution readers about the specificity of these geographic terms and ethnonyms, noting in his al-Muqaddimah that "The inhabitants of the first and second zones in the south are called Abyssinians, the Zanj and the Sudan. The name Abyssinia however is restricted to those who live opposite Mecca and Yemen, and the name Zanj is restricted to those who live along the Indian Ocean."20

Translation of the toponyms found on the simplified copy of al-Idrisi’s world map by Joachim Lelewel.

The names of the different peoples from each African region were also similar to the broad geographic terms for the places where they came from, such as the 'Sudan' from West Africa, the ‘Nuba’ from Sudan, the ‘Habasha’ from Ethiopia, and the Zanj from East Africa. While some writers used these terms inconsistently, such as the term ‘Barbar’ which could be used for Berber, Somali, and Nubian Muslims, or Zanj which could be used for some non-Muslim groups in 19th-century west-Africa; the majority of writers used them as names of specific peoples in precise locations on a map.21

On the other hand, the Muslims who came from these regions were often named after the most prominent state, such as the Takruri of West Africa who were named after the kingdom of Takrur, and the Jabarti of the northern Horn of Africa who were named after the region of Jabart in the Ifat and Adal sultanate22. It’s for this reason that the hostels of Al-Azhar in the 18th century were named after each community; the Riwāq al-Dakārinah for scholars from Takrūr, the Riwāq Dakārnah Sāliḥ for scholars from Kanem, and the Riwāq al-Burnīya for scholars from Bornu.23 Others recorded in the 19th century include the Riwāq al-Djabartiya for scholars from the Somali coast, Riwāq al-Barabira for Nubian scholars (from modern Sudan).24

While each community concentrated around their hostels and their respective shayks, the different scholars of al-Ahzar frequently intermingled as the roles of ''teacher' and 'student' changed depending on an individual scholar's expertise on a subject.

For example, prominent West African scholars such as Muhammad al-Kashinawi (d. 1741) from the city of Katsina, southwest of Bornu, were among the teachers of Hasan al-Jabarti (d. 1774), the father of the famous historian ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Jabartī (d. 1825) whose family was originally from the region around Zeila in northern Somalia. Abd al-Raḥmān al-Jabartī included Muhammad al-Kashinawi in his biography of important scholars and listed many of the latter’s works. Another prominent West African scholar at Al-Azhar was the 18th-century Shaykh al-Burnāwī from Bornu whose students and contemporaries included prominent Egyptian and Moroccan scholars such as Abd al-Wahhab al-Tāzī (d. 1791) .25

Both Muhammad al-Kashinawi and Shaykh al-Burnāwī acquired their education in West Africa, specifically in Bornu where most of their teachers were attested before they traveled to Cairo to teach. It’s in this context that the writings of scholars from Bornu such as the 17th-century jurist Muhammad al-Barnawi, mentioned in the introduction, became known in Egypt among the leading administrators of al-Azhar like Mustafa al-Bulaqi (d. 1847) who was the chief Mufti (jurisconsult) of the Maliki legal school of Egypt and Hasan al-Quwaysini, who was the rector of the college itself.26

The Bornu scholar Al-Barnawi, also known as Hajirami in West Africa, was the imam of one of the mosques in the Bornu capital Ngazargamu, and was a prominent teacher before he died in 1746. He is known to have authored several works, the best known of which was his didactic work of legal theory titled 'Shurb al-zulal' (Drinking pure water) written between 1689 and 1707. The work follows the established Maliki tradition of Bornu, citing older and contemporary scholars from across the Muslim world including Granada, Fez, Cairo, and Timbuktu. In the early 19th century, the Maliki mufti al-Bulaqi wrote a commentary on al-Barnawi's which he titled Qaşidat al - Manhal al-Sayyāl li - man arāda Shurb al-Zulal. Many copies of the latter found their way back to the manuscript collections of northern Nigeria.27

Copy of al-Mustafa al-Bulaqi’s commentary, Bibliotheque Nationale Paris, Arabe 5708, fol 104-115.

After the Portuguese sailed around the southern tip of Africa in 1488, the classical geography of al-Idrisi was updated in European maps, along with many of the geographic terms of Muslim cartography. Over the centuries, additional information about the continent was acquired, initially from African travelers from Ethiopia and Kongo who visited southern Europe and western Europe, and later by European travelers such as James Bruce and Mungo Park who visited East and West Africa in the eighteenth century.

As more information about Africa became available to European writers, it was included in the dominant discourses of Western colonialism —a political and social order that purported a racial and cultural superiority of the West over non-Western societies. Such colonial discourses were first developed in the Americas by writers such as John Locke28 and were furthered by Immanuel Kant29 and Georg Hegel in their philosophies of world history. Hegel in particular popularized the conceptual divide between "North Africa" (which he called “European Africa”), and the rest of Africa (which he called "Africa proper"), claiming the former owes its development to foreigners while condemning the latter as "unhistorical".30

An 18th century European map of Africa in which ‘Negroland’, ‘Nubia’ and ‘Abissinia’ are separated from ‘Barbaria’, ‘Biledugerid’, and ‘Egypt’ by the ‘Zaara desert’ and the ‘desert of Barca’.

These writers provided a rationale for colonial expansion and their “racial-geographical” hierarchies would inform patterns of colonial administration and education, especially in the French-controlled regions of the Maghreb and West Africa, as well as in British-controlled Egypt and Sudan. The French and British advanced a Western epistemological understanding of their colonies, classifying races, cultures, and geographies, while disregarding local knowledge. Pre-existing concepts of ethnicity were racialized, and new identities were created that defined what was “indigenous” against what was considered “foreign”.31

The institutionalization of disciplines of knowledge production in the nineteenth century transformed concepts of History and Geography into purely scientific disciplines, thus producing particular Geo-historical subjectivities such as the "Arab-Islamic" on the one hand, and "African" on the other. In this new conceptual framework, the spatial designations like ‘North Africa’ and ‘Sub-Saharan Africa’ were imaged as separate geographical entities. Any shared traditions they have are assumed to be the product of unidirectional links in which the South is subordinate to the North.32

The modern historiography of the Islamic world also emerged in the context of European colonialism and largely retained its Euro-American categorization of geographic entities and peoples. The Sahara was thus re-imagined as a great dividing gulf between distinct societies separating North from South, the “Black/African” from “White/Arab”.33 The old ethnonyms such as 'Sudan', 'Habash', and ‘Zanj’ were translated as 'Black' —a term developed in the Americas and transferred to Africa—, and the vast geographic regions of Bilad al-Sudan, Bilad al-Habasha, and Bilad-al-Zanj were collapsed into 'Sub-Saharan' Africa.

Gone are the complexities of terms such as the Takruri of Sudan, or the Jabarti of Habash, and in come rigid terms such as 'Sub-Saharan Muslims' from 'Black Africa'. The intellectual and cultural exchanges between societies such as Egypt and Bornu, where rulers recognized each other as equals and scholars such as al-Suyuti and al-Barnawi were known in either region, are re-imagined as unidirectional exchanges that subordinate one region to the other. Contacts between the two regions are approached through essentialized narratives that were re-interpreted to fit with Eurocentric concepts of 'Race.'34

While recent scholarship has discarded the more rigid colonial terminologies, the influence of modern nationalist movements still weighs heavy on the conceptual grammar and categories used to define Africa’s geographic spaces. Despite their origin as anti-colonial movements, some of the nationalist movements on the continent tended to emphasize colonial concepts of "indigeneity" and"national identity" and assign them anachronistically to different peoples and places in history.

For this reason, the use of the terms ‘North Africa’ and ‘Sub-Saharan Africa’ is today considered politically and culturally expedient, both negatively and positively —by those who want to reinforce colonial narratives of Africa's separation and those who wish to subvert them.

Whether it was a product of the contradiction between the Arab nationalism championed by Egypt’s Abdel Nasser that sought to 'unite' the predominantly Arab-speaking communities, that clashed with —but at times supported— Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah whose Pan-Africansm movement included the North.35 Or it is a product of the continued instance of UN agencies on the creation of new and poorly-defined geopolitical concepts like MENA ("The Middle East and North Africa")36 and the other fanciful acronyms like WANA, MENASA, or even MARS37. The result was the same, as communities on both sides of the divide internalized these new identities, created new patterns of exclusion, and imbued them with historical significance.

But for whatever reason the term 'Sub Saharan' Africa exists today, it did not exist in the pre-colonial world in which the societies of Mamluk Egypt and Bornu flourished.

It wasn't found on the maps of Muslim geographers, who thought the West African kingdoms were located within the Sahara itself and nothing lived further south. It wasn't present in the geo-political ordering of the Muslim world where Bornu's ruler Ali Dunama, even in the throes of civil war, addressed his Egyptian peer as his equal and retained the more prestigious titles for himself. In the same vein, his successor Idris Alooma would only address the Ottoman sultan as 'King' but rank himself higher as Caliph38, similar to how Mansa Musa refused to bow to the Mamluk sultan, but was nevertheless generously hosted in Cairo.

The world in which al-Suyuti and al-Barnawi were living had no concept of modern national identities with clearly defined boundaries, It had its own ways of ordering spaces and societies that had little in common with the colonial world that came after. It was a world in which scholars from what are today the modern countries of Nigeria, Somalia, and Morocco could meet in Egypt to teach and learn from each other, without defining themselves using these modern geo-political concepts.

It was a world in which Sub-Saharan Africa was an anachronism, a myth, projected backward in colonial imaginary.

students at the Al-azhar University in Cairo, early 20th-century postcard.

The northern Horn of Africa produced some of Africa’s oldest intellectual traditions that include the famous historian Abdul Rahman al-Jabarti of Ottoman-Egypt. Read more about the intellectual history of the Northern Horn on Patreon:

Al-Suyūṭī, a polymath of the Mamlūk period edited by Antonella Ghersetti

Jalal ad-Din As-Suyuti's Relations with the People of Takrur by E.M. Sartain pg pg 195

Du lac Tchad à la Mecque by Rémi Dewière pg 223, 249.

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants pg 106, Ethnoarchaeology of Shuwa-Arab Settlements By Augustin Holl pg 12-13

Mamluk Cairo, a Crossroads for Embassies: Studies on Diplomacy and Diplomatics edited by Frédéric Bauden, Malika Dekkiche pg 674-678)

Jalal ad-Din As-Suyuti's Relations with the People of Takrur by E.M. Sartain pg 195)

Tafsīr Sources in Annotated Qur’anic Manuscripts from Early Borno by Dmitry Bondarev pg 25-57

A Geography of Jihad. Jihadist Concepts of Space and Sokoto Warfare by Stephanie Zehnle pg 79, 85-101.

A Geography of Jihad. Jihadist Concepts of Space and Sokoto Warfare by Stephanie Zehnle pg 89)

A Geography of Jihad. Jihadist Concepts of Space and Sokoto Warfare by Stephanie Zehnle pg 94)

The Image of Africans in Arabic Literature : Some Unpublished Manuscripts by by Akbar Muhammad 47-51

Reader in al-Jahiz: The Epistolary Rhetoric of an Arabic Prose Master By Thomas Hefter

The Sahara: Past, Present and Future edited by Jeremy Keenan pg 96

Arabic External Sources for the History of Africa to the South of Sahara Tadeusz Lewicki

Church and State in Ethiopia, 1270-1527 by Taddesse Tamrat pg 12

New Encyclopedia of Africa, Volume 1, edited by John Middleton pg 208)

A Geography of Jihad. Jihadist Concepts of Space and Sokoto Warfare by Stephanie Zehnle pg 80-84, Cartography between Christian Europe and the Arabic-Islamic World pg 74-87

A Region of the Mind: Medieval Arab Views of African Geography and Ethnography and Their Legacy by John O. Hunwick pg 106-120

Ibn Khaldun, the maqadimma: an introduction to history, by Franz Rosenthal, pg 60-61)

Models of the World and Categorical Models: The 'Enslavable Barbarian' as a Mobile Classificatory Label" by Paulo Fernando de Moraes Farias.

Takrur the History of a Name by 'Umar Al-Naqar pg 365-370, Islamic principalities in southeast Ethiopia pg 31

Islamic Scholarship in Africa by Ousmane Oumar Kane pg 8)

E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam: 1913-1936. A - Bābā Beg, Volume 1 by E. J. Brill pg 533-534

Islamic Scholarship in Africa: New Directions and Global Contexts pg 30-32, PhD thesis) Al-Azhar and the Orders of Knowledge by Dahlia El-Tayeb Gubara pg 213.

Islamic Reform and Conservatism: Al-Azhar and the Evolution of Modern Sunni Islam by Indira Falk Gesink pg 90, 28

The Arabic Literature of Nigeria to 1804 by A.D.H. Bivar pg 130-131, Arabic Literature of Africa Vol.2 edited by John O. Hunwick, Rex Séan O'Fahey pg 41)

John Locke and America: The Defence of English Colonialism By Barbara Arneil

Black Rights/white Wrongs: The Critique of Racial Liberalism By Charles Wade Mills

Hegel and the Third World by Teshale Tibebu pg 224)

The Invention of the Maghreb: Between Africa and the Middle East By Abdelmajid Hannoum, The Walking Qurʼan: Islamic Education, Embodied Knowledge, and History in West Africa by Rudolph T. Ware, Living with Colonialism: Nationalism and Culture in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan By Heather J. Sharkey.

(PhD thesis) Al-Azhar and the Orders of Knowledge by Dahlia El-Tayeb Gubara, pg 189-192

On Trans-Saharan Trails: Islamic Law, Trade Networks, and Cross-Cultural Exchange in Nineteenth-Century Western Africa by Ghislaine Lydon pg 36-46

The Walking Qurʼan: Islamic Education, Embodied Knowledge, and History in West Africa by Rudolph T. Ware pg 21-36

Nkrumaism and African Nationalism by Matteo Grilli, The Arabs and Africa edited by Khair El-Din Haseeb)

The Multidimensionality of Regions in World Politics by Paul J. Kohlenberg,

Another Cartography is Possible: Relocating the Middle East and North Africa by Harun Rasiah

At what point, away from the scholarly circles you refer to did the inhabitants of the continent start seeing themselves as African? Even in the scholarly world, as you say people didn't differentiate between North and sub Saharan Africa but they didn't seem to identify as Africans either in a continental sense only some form of regional identity.