Historical links between the Ottoman empire and Sudanic Africa (1574-1880)

travel and exchanges between Istanbul and the states of; Bornu, Funj, Darfur and Massina.

In 1574, an embassy from the empire of Bornu arrived at the Ottoman capital of Istanbul after having travelled more than 4,000 km from Ngazargamu in north-eastern Nigeria. This exceptional visit by an African kingdom to the Ottoman capital was the first of several diplomatic and intellectual exchanges between Istanbul and the kingdoms of Sudanic Africa -a broad belt of states extending from modern Senegal to Sudan.

In the three centuries after the Bornu visit of Istanbul; travelers and scholars from the Sudanic kingdoms and the Ottoman capital criss-crossed the meditteranean in a pattern of political and intellectual exchanges that lasted well into the colonial era.

This article explores the historic links between the Ottoman empire and Sudanic Africa, focusing on the travel of diplomats and scholars between Istanbul and the kingdoms of Bornu, Funj, Darfur and Massina.

Map showing the kingdoms of Sudanic Africa and the Ottoman empire.1

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more on African history and keep this blog free for all:

Diplomatic links between the Bornu empire and the Ottomans: envoys from Mai Idris Alooma in 16th century Istanbul

The Ottoman empire was founded at the turn of the 13th century, growing into a large Mediterranean power by the early 16th century following a series of sucessful campaigns into eastern Europe, western Asia and North-Africa. Like other large empires which had come before it, Ottoman campaigns into Sudanic Africa were largely unsuccessful. The earliest of these campaigns were undertaken against the Funj kingdom in modern Sudan, more consequential however, were the proxy wars between the Ottomans and the Bornu empire in the region of southern Libya.

The empire of Bornu was founded during the late 11th century in the lake chad basin. The rulers of Bornu maintained an active presence in southern Libya since the 12th century, and regulary sent diplomats to Tripoli and Egypt from the 14th century onwards. Bornu's rulers, scholars and pilgrims frequently travelled through the regions of Tripoli, Egypt, the Hejaz (Mecca & Medina) and Jerusalem. These places would later be taken over by the Ottomans in the early 16th century, and Bornu would have been aware of these new authorities.

In 1534, the Bornu ruler sent an embassy to the Ottoman outpost of Tajura near Tripoli, the latter of which was at the time under the Knights of Malta before it was conquered by the Ottomans in 1551. In the same year of the Ottoman conquest of Tripoli, the Bornu ruler sent an embassy to the new occupants, with another in 1560 which established cordial relations between Tripoli and Bornu. But by the early 1570s, relations between Bornu and Ottoman-Tripoli broke down when several campaigns from Tripoli were directed into the Fezzan region of southern Libya which was controlled by Bornu’s dependents.2

In the year 1574, the Bornu ruler Mai Idris Alooma sent a diplomatic delegation of five to Istanbul in response to the Ottoman advance into Bornu's territories in southern Libya. This embassy was headed by a Bornu scholar named El-Hajj Yusuf, and it remained in Istanbul for four years before returning to Bornu around 1577. In response to this embassy, the Ottoman sultan sent an embassy to the Bornu capital Ngazargamu (in North-eastern Nigeria) which arrived in 1578.3

More than 10 archival documents survive of this embassy, the bulk of which are official letters by the Ottoman sultan Murad III adressed to the Bornu ruler and the Ottoman governor of Tripoli. The Ottomans agreed to most of the requests of the Bornu ruler except handing over the Fezzan region, something that Idris Alooma would solve on his own when the Ottoman garrison in the Fezzan was killed around 15854. Yet despite this brief period of conflict, relations between the Ottomans and Bornu flourished, with Ottoman firearms and European slave-soldiers being sent to Bornu to bolster its military.

The exchange of embassies between the Ottomans and the Bornu rulers is mentioned in the 1578 Bornu chronicle titled kitāb ġazawāt Kānim (Book of the Conquests of Kanem), whose author Aḥmad ibn Furṭū wrote that;

"Did you ever see a king equal to our sultan or close to him, when the lord of Dabulah [Istanbul] sent his emissaries from his country with sweet words, sincere and requested affection and for a desired union? Alas, in truth, all sultans are inferior to the Bornu sultan."

Ibn Furtu gives the Ottoman sultan a diminutive title of malik (King); compared to the title 'Sultan' which was used for Bornu's neighbors: Kanem and Mandara, while the Bornu ruler was given the prestigious title 'Caliph'. This reflected the political tensions between the Ottomans and Bornu, as much as it served to legitimate the authority of the Bornu rulers relative to their regional peers.5

Contacts between Bornu and the Ottomans were thereafter confined to Tripoli, Egypt and the Hejaz, without direct visits between Istanbul and Ngazargamu. An exceptional decree issued by the Ottoman sultan in Istanbul during the early 17th century was copied in Bornu at an uncertain date6, but aside from this, the intellectual cultures of Bornu contain no scholars from Istanbul, nor did Bornu's scholars visit the Ottoman capital, opting to confine their activities to scholary communities in Tripoli and Egypt.

ruined sections of Idris Alooma’s 16th century palace at Gamboru, Nigeria

The Ottoman-Funj war and an Ottoman visitor in 17th century Sennar.

The Funj kingdom was founded around 1504 shortly before the Ottoman conquest of Egypt in 1517. Expanding northwards from its capital Sennar, the Funj would encounter the Ottomans at the red-sea port of Suakin as well as the town of Qasr Ibrim in lower Nubia.

A report by a Ottoman naval officer in 1525, which contains a dismissive description of the Funj and Ethiopian states as well as recommendations to conquer them with an army of just 1,000 soldiers, indicates that the Ottomans drastically underestimated their opponent. The ottoman general Özdemir Pasha had suceeded in creating the small red-sea province of Habesh in 1554 (which was essentially just a group of islands and towns between Suakin and Massawa), but his campaign into Funj territory from Suakin was met with resistance from his own troops.7

In 1560s the Ottomans occupied the fort of Qasr Ibrim and by 1577, had moved their armies south intending to conquer the Funj kingdom. According to an account written around 1589, the Ottoman army advanced against the city of old Dongola on the Nile with many boats, and the Funj army met them nearby at Hannik where a battle ensued that ended with an Ottoman defeat and withdraw (with just one boat surviving). The Ottoman-Funj border was from then on established at Sai island, although it would be gradually moved north to Ibrim.8

In the suceeding century following the Ottoman defeat, relations between the Funj kingdom and their northern neighbor were normalized as trade and travel increased between the two regions. In 1672/3, the Funj kingdom was visited by the Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi on his journey through north-east Africa. Starting at Ibrim in late 1672, Evliya set off with a party of 20 within a merchant carravan of about 800 traders mostly from Funjistan (ie: Funj), carrying letters from the Ottoman governor of Egypt addressed to the Funj ruler to ensure Evliya's safety.9

Evliya Celebi’s journey through the Funj kingdom and North-east Africa, map by Michael D. Sheridan

Late medieval ruins on Sai Island

Detail of a 17th century illustration depicting Evliya Celebi

Evliya arrived in the region of 'Berberistan'; the northern tributary province of Berber in the Funj kingdom, which begun at Sai Island. He passed through several fortified towns before arriving at the provincial capital of Dongola. The province was ruled by a certain king 'Huseyin Beg' who recognized the Funj ruler at Sennar as his suzerain. Evliya stayed in Berber for several weeks before proceeding to old Dongola (the former capital of Makuria) where the Funj territories formally begun.10

From old Dongola, Evliya passes through several castellated towns before he reaches the city of Arbaji within the core Funj territories. He stopped over for a few days where he had a rather uncomfortable meeting with the local ruler before proceeding to the Funj capital sennar where he stayed for over a month. Sennar was described as a large city with several quarters surrounded by a 3-km long wall, pierced by three large gates and defended by 50 cannons. The Funj king (Badi II r. 1644-1681) controlled a vast territory, reportedly with as many as 645 cities and 1,500 fortresses. King Badi received the official letters from the Egyptian governor that Evliya had brought with him, and wrote his own letters addressed to the sender. The Funj king accompanied Evliya on a tour of the kingdom's southern territories, afterwhich they both returned to Sennar where the King gave Evliya provisions for his return journey. But upon reaching Arbaji where he encountered Jabarti merchants (Ethiopian Muslims), Evliya decided to head east through the northern frontier of the Ethiopian state to the red sea coast.11

The last leg of Evliya's trip took him through northern Dembiya (ie: Gondarine-Ethiopia), proceeding to the red sea coastal city of suakin before turning south to the coastal cities of the horn including Massawa and Zeila, and later retracing his route back to Egypt. Evliya arrived in Cairo in April 1673 accompanied by three Funj envoys, presenting the gifts from the Funj king and his letters to the governor of Egypt.12

Ruins of a Christian monastery complex at old Dongola, similar ruins are described in Evliya’s account

ruins of a ‘Diffi’ fortified castle-house on Jawgul island, the kind that appears frequently in Evliya’s account of the Funj kingdom

Ruins of a mosque in Sennar13, the Funj capital fell into decline in the early 19th century when it was abandoned.

Diplomatic and Intellectual links between the kingdoms of Funj and Darfur, and the Ottomans: traveling scholars and envoys from the eastern Sudan in Istanbul

While most diplomatic and intellectual exchanges between the Ottomans and the Funj were confined to Egypt, some Funj scholars travelled across the Ottoman domains as far as the empire's capital at Istanbul. The earliest documented Funj scholar to reach Istanbul was Ahmad Idrìs al-Sinnàrì (b. 1746). He travelled from Funj to Yemen for further studies, moving through the Hejaz and from there to Egypt. He later travelled to Istanbul and to Aleppo where he would live out the rest of his life. Another traveler from the Funj region was Ali al-Qus (b. 1788), he studied at al-Azhar, before setting out on his extensive travels, during which he visited Syria, Crete, the Hijaz Yemen and Istanbul, before returning to settle at Dongola shortly after the fall of the Funj kingdom.14

While the Funj kingdom didn't send envoys directly to Istanbul, its western neighbor, the kingdom of Darfur, sent an embassy directly to the Ottoman sultan after conflicts with the governor of Ottoman-Egypt. On April 7th, 1792, the Darfur king Abd al-Rahman (r. 1787–1801). sent an envoy to Istanbul with gifts for Selim III and letters describing the former's campaigns in the frontiers15. The Darfur envoy informed the Ottoman sultan that the latter's officials in Egypt were doing injustice to merchants of Darfur and demanded that the sultan sends an imperial edict against their actions. The sultan likely agreed to the requests of the Darfur king, who was also given the honorific title al-Rashid (the just), a title that would frequently appear on the royal seals of Darfur.16

Intellectual and diplomatic exchanges between the Ottomans and the eastern Sudanic kingdoms continued throughout the 19th century, even after the brief French conquest of Egypt (the Darfur king also sent an embassy to Napoleon in 1800), and the Egyptian conquest of Sennar in the 1821.

Letter from ʿAbd al-Raḥmān of Darfur to Selim III,. Cumhurbaşkanliği Osmanli Arşivi, Istanbul

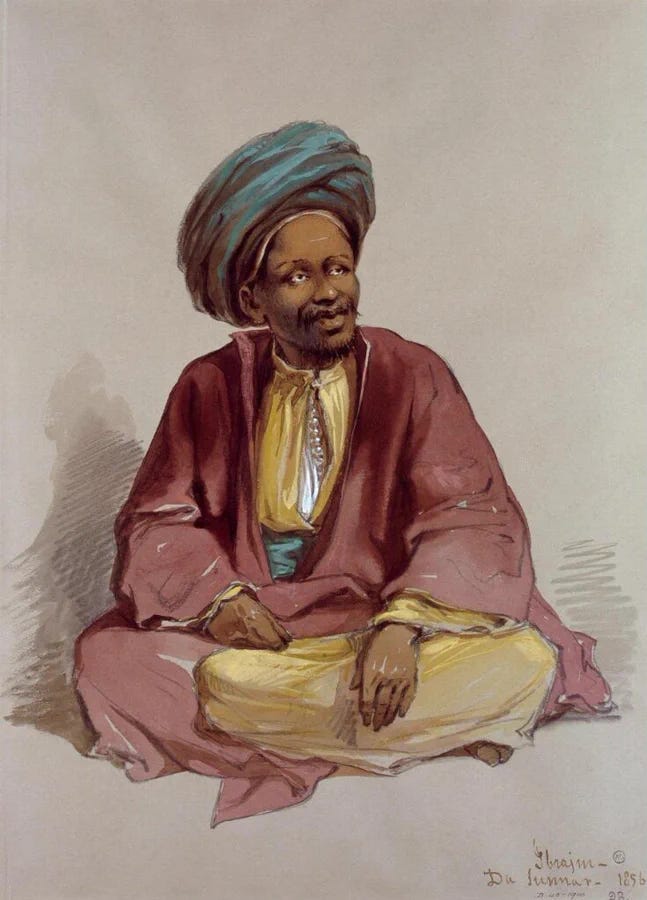

painting of Ibrahim, a Sudanese muslim from Sennar in Istanbul ca. 1856, V&A museum

Ottoman links with the western-Sudanic kingdoms: A traveling scholar from Massina in Istanbul

Unlike the central and eastern Sudan which bordered Ottoman provinces, the western Sudanic states had little diplomatic contact with the Ottomans outside Egypt and the Hejaz, nor was the empire recognized as a major Muslim power before the 18th century. When a Portuguese embassy to Mali reached the court of Mansa Mahmud II in 1480s, the Mali ruler mentioned that he hadn't received a Christian envoy before, and the only major powers he recognized were the King of Yemen, the king of Baghdad, the King of Cairo and the King of Mali. Similary, the Ottomans don't appear in the 17th century Timbuktu chronicles despite the empire having seized control of Egypt and the Hejaz more than a century before and many west-African scholars having travelled through Ottoman domains.17

While the Ottomans didn't frequently appear in early west-African writings, they are increasingly mentioned in the 18th and 19th century centuries. The 19th century chronicle Ta'rikh al-fattash, which is mostly based on the 17th century Timbuktu chronicles, mentions that: "We have heard the common people of our time say that there are four sultans in the world, not counting the supreme sultan, and they are the Sultan of Baghdad, the Sultan of Egypt, the Sultan of Bornu, and the Sultan of Mali." The chronicler added a gloss which reads 'this is the sultan of Istanbul' in place of the 'supreme sultan'.18

The chronicler of the Ta'rikh al-fattash was writing from the empire of Massina, and its from here that atleast one western Sudanic scholar is known to have travelled to Istanbul in the mid 19th century. The scholar Muhammad Salma al-Zurruq (b. 1845) was born in the city of Djenne (Mali) into a chiefly family. He set off for pilgrimage early in his youth afterwhich he visited Istanbul, where he stayed for some time and met Muhammad Zhafir al-Madani, son of the founder of the Madaniyya order, Zhafir al-Madani, who acted as an agent of the Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II (r. 1876-1909), with the Sufi orders in Ottoman north-Africa. Muhammad Salma was able to establish an excellent rapport with the sultan who supplied him with documents guaranteeing his safe travel through Ottoman territories. Muhammad Salma travelled extensively in Ottoman territories and finally arrived in the Moroccan capital of Fez in 1888, later returning to Mali in 1890 on the eve of the French conquest.19

Djenne street scene, ca. 1906

Sultan Abdul Hamid greatly transformed ottoman relations with Sudanic Africa, set in the context of the colonial scramble. But lacking the capacity to undertake distant military campaigns into the region, the Ottomans relied on religious orders to assert its political claims over parts of Africa which it never formally controlled. Relying on its alliances with the Sanusi order that was active in the Fezzan and the kingdoms of Wadai and Bornu, Ottoman agents travelled to parts of the region to initiate a new (albeit brief) era of diplomatic exchange with the central Sudan. 20

Ottoman agents also travelled beyond the Sudanic regions to Lagos (Nigeria), Cape colony, Zanzibar, Ethiopia and even to the African Muslim community in Brazil21. Similary, African kingdoms sent envoys and scholars to the Ottoman capital to forge anti-colonial alliances. The diplomatic ties between the Ottomans and African kingdoms such as Darfur under Ali Dinar, lasted until the collapse of the Ottoman empire after the first world war.22

This late phase of African-Ottoman links is a fascinating topic that will be explored later, covering the international diplomatic strategies African states used to resist the colonial expansion.

The Shitta-Bey Mosque in Lagos, built in 1891 by Mohammed Shitta Bey (ca. 1824-1895) a son of a freed-slave from Freetown who originally came from Brazil. The most important figure at the mosque’s opening was the Ottoman sultan’s representative Abdullah Quilliam (1856-1932), not long after another ottoman agent, Abd ar-Rahman al-Baghdadi, had visited the African Muslims of Brazil.

In the 9th century, Italy was home to the only independent Muslim state in Europe that was ruled by Berbers and West-Africans, read more about the kingdom of Bari on my latest Patreon post:

Mohammed Shitta Bey was one of several descendants of freed-slaves who settled on the west-African coast and made a significant contribution to the region’s economic development and modernization during the 19th century. Read more about it here;

adopted from Rémi Dewière

Mai Idris of Bornu and the Ottoman Turks by BG Martin pg 472-473, Du lac Tchad à la Mecque: Le sultanat du Borno by Rémi Dewière pg 29-30)

The relationship between the Ottoman Empire and Kanem-Bornu During the reign of Sultan Murad III by Sebastian Flynn pg 113-118

Du lac Tchad à la Mecque: Le sultanat du Borno by Rémi Dewière pg 34-35, 159

The Slave and the Scholar: Representing Africa in the World from Early Modern Tripoli to Borno by Rémi Dewière pg 52-53)

Doubt, Scholarship and Society in 17th-Century Central Sudanic Africa By Dorrit van Dalen pg 36

The Ottomans and the Funj sultanate in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries by A.C.S. Peacock pg 92-94

Kingdoms of the Sudan By R.S. O'Fahey, J.L. Spaulding pg 35)

Nil Yolculuğu: Mısır, Sudan, Habeşistan by Nuran Tezcan

Ottoman Explorations of the Nile by Robert Dankoff pg 251-256)

Ottoman Explorations of the Nile by Robert Dankoff pg 257-301)

Ottoman Explorations of the Nile by Robert Dankoff pg 361)

image by sudanheritageproject

The Transmission of Learning in Islamic Africa by Scott Reese pg 146, Arabic Literature of Africa Vol1 by John O. Hunwick pg 146,

An Embassy from the Sultan of Darfur to the Sublime Porte in 1791 by A.C.S. Peacock

, Black Pearl and White Tulip: A History of Ottoman Africa by Şakir Batmaz pg 42, Kingdoms of the Sudan By R.S. O'Fahey, J.L. Spaulding pg 162)

Wangara, Akan and Portuguese 1 by Ivor Wilks pg 339)

Wangara, Akan and Portuguese 1 by Ivor Wilks pg 339 n. 36)

La Tijâniyya. Une confrérie musulmane à la conquête de l'Afrique by Jean-Louis Triaud pg 397-398)

The Ottoman Scramble for Africa By Mostafa Minawi

Osmanlı-Afrika İlişkileri by Ahmet Kavas, The Politicization of Islam: Reconstructing Identity, State, Faith, and Community in the Late Ottoman State by Kemal H. Karpat, Illuminating the Blackness: Blacks and African Muslims in Brazil By Habeeb Akande

An Islamic Alliance: Ali Dinar and the Sanusiyya, 1906-1916 By Jay Spaulding

Excellent historical review as always. Thank you!