The 'hidden founders' of African studies in Europe: African intellectuals in the Holy Roman Empire and the German Reich ca. 1652-1918.

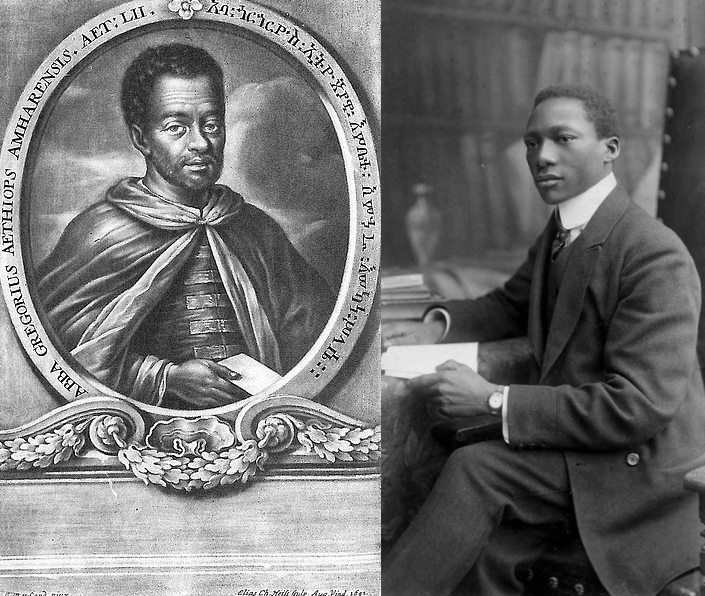

In June 1652, the Ethiopian scholar Abba Gorgoryos reached the city of Nuremburg in what was then the Holy Roman Empire (modern Germany) where he met Hiob Ludolf, an envoy and linguist whom later generations of ‘Ethiopists’ would regard as the founder of Ethiopian studies in Europe.

Ludolf had first met Gorgoryos in Rome, where a long-established diasporic community of Ethiopian scholars had sparked his interest in Ethiopian studies. Following an invitation from the Duke of Saxe Gotha (part of the Holy Roman Empire), Gorgoryos was joined by Ludolf and invited to stay at the Duke's Friedenstein Castle. For several weeks, the Ethiopian scholar was involved in extensive discussions on Ethiopian history and culture, while correcting the little available literature they had.1

In his 1681 publication titled 'Historia Aethiopica', Ludolf devoted most of the book's preface to the Ethiopian scholar in recognition of his contribution, referring to him as a “person of great credit, and on whose authority anyone may securely rely.”2

Portrait of Abba Gorgoryos in the ‘Historia Aethiopica’ by Hiob Ludolf

Ruins of Susenyos’s Palace at Dänqäz, near Gondar, Ethiopia. Photo by Metalocus. Gorgoryos was a high-ranking aristocrat and a close adviser to emperor Susenyos and fled the country after the emperor’s abdication in 1632.3

A little over two centuries later in 1896, the Hausa scholar Imam Umaru established a school in the small town of Kete-Krachi in what would become the German colony of Togo in west-Africa. One of his students was the German linguist Adam Mischlich, who is counted among the earliest scholars of Hausa studies in Europe.

Umaru composed several manuscripts for his students, including a monumental anthropological work on Hausa society titled 'Tarihin Kasar Hausa' (History of Hausaland). Mischlich translated this and several other works of Umaru which he published in several journal articles in 1909, and in his 1947 book Über die Kulturen im Mittel-Sudan (About the Cultures of Central Sudan).4

However, unlike Ludolf, Mischlich tells us nothing about Umaru in his articles, and devotes less than two pages to him in his book. Imam Umaru wrote more than 130 works on many different topics. Many were preserved in private libraries by his students in West Africa, and at least 40 of them were later transferred to institutions such as the University of Ghana and Nigeria’s National Archives, in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

It wasn't until 1977 when Umaru's original manuscripts used in Mischlich's publications were re-translated, that his contributions to modern Hausa historiography and African studies in general would be fully appreciated by a new generation of scholars.5

Photo of Al-Hajj Umaru al-Kanawi (1858-1934) in Togo and his birthplace of Kano in Nigeria during the early 20th century.

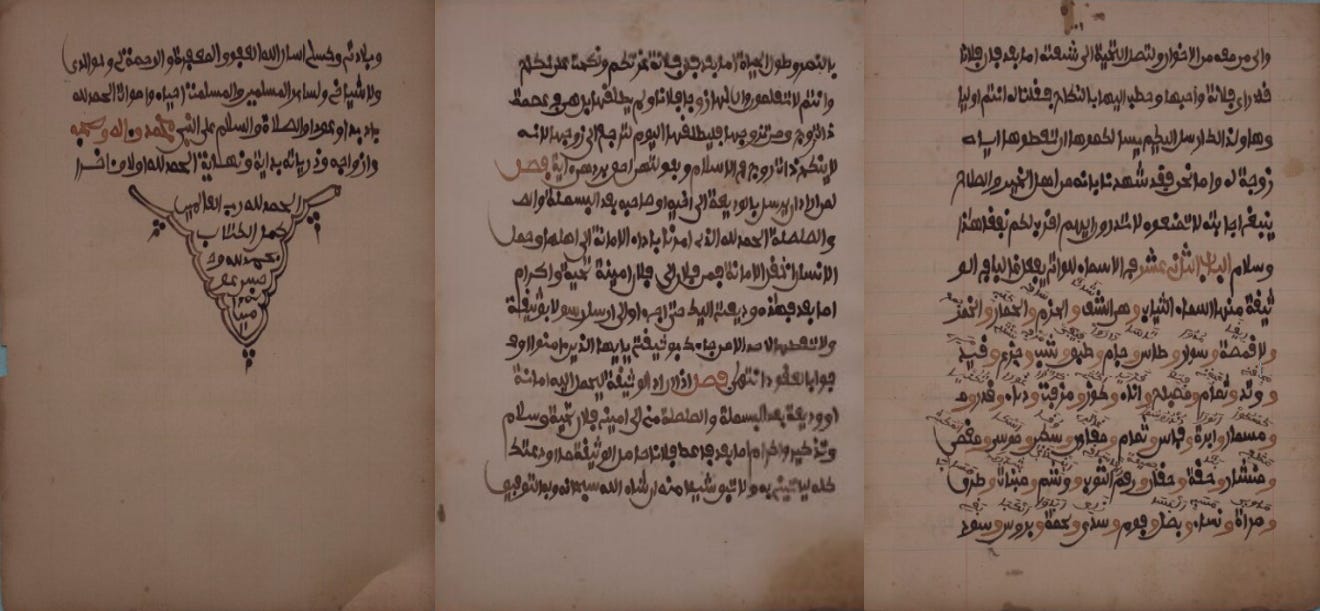

Umaru’s first work in 1877 (at the age of 20); a 20-page letter writing manual; now at Kaduna National Archives, Nigeria (no. L/AR20/1)

The broad field of African studies, which includes anthropology, linguistics, and history, has often recognized a number of ‘founding figures’ who are virtually all European scholars of the colonial era, and whose work is considered central to the establishment of the modern study of African societies and cultures. However, later generations of scholars have uncovered the work of African scholars and informants whose invaluable research formed the basis of much of the work published by their European colleagues.

While the efforts of these African intellectuals were at times noted, they were not thought of as co-authors and did not receive much praise for their labor. Until recently, little was known about their contributions to the ethnographic and linguistic scholarship of Africa, and their work remained hidden in the footnotes of their more famous European peers who published under their own names what was effectively the work of African intellectuals.

Focusing on Germany in particular, a notable example is the linguist Carl Meinhof (1857–1944), who is widely regarded as the founder of African studies* in German universities (Afrikanistik), beginning in 1887 with the ‘Seminar of Oriental Languages’ (SOL) at the University of Berlin and the Hamburg Colonial Institute in 1908, where he took up the first professorial positions in both institutions. Meinhof is renowned for his comprehensive classification scheme for African languages and for his highly influential publications on Bantu languages.6

[*note that such ‘African studies’ were expressly concerned with serving European colonial interests rather than being purely “scientific” pursuits7]

The African studies pioneered by Meinhof and his colleagues in Germany, such as the linguists; Carl Gotthilf Büttner (d. 1893) and Carl Velten (d. 1935), were very dependent on several African scholars and informants who provided first-hand information on their own societies. Some of these Africans traveled to Germany to serve as lecturers at the SOL and in Hamburg, but their contribution to the founding of African studies remained largely unknown.8

A list of these hidden African founders includes the Duala prince Njo Dibone, who traveled from Cameroon to Germany in 1885 to teach the then-pastor Carl Meinhof about the Duala language and other related languages. Dibone also taught Meinhof aspects of Duala anthropology and mythology, some of which were compiled by Dibone in his 1889 publication; Märchen aus Kamerun (Fairy Tales from Cameroon).9

Dibone’s teaching marked the beginning of Meinhof's career as a linguist and ‘ethnographer’ of Africa resulting in Meinhof's publication of such foundational works like “Preliminary Remarks to a Comparative Dictionary of Bantu” (1895), and Bantu Phonology (1899), which were the first among the numerous articles and books he published. However, the relationship between Meinhof and Dibone later deteriorated after the latter requested financial compensation for his services.10

Around the same time that Dibone was teaching Meinhof, the latter's peers at the SOL, such as Carl Büttner, were learning the Swahili language from the East African lecturers; Sulaiman bin Said and Amur al-Omeri, who travelled from Zanzibar to Berlin in 1889 and 1891 respectively. The two Swahili lecturers had many famous students at the SOL including the abovementioned Carl Velten, and they also published several works on East African societies, customs, and languages, as well as a travel account and description of Berlin by Amur al-Omeri.11

Büttner was originally a missionary in what is today Namibia and a strong advocate for German colonialism, after which he became the first “teacher” of Swahili at the SOL in 1887 despite having little knowledge of the language prior to the arrival of the two lecturers.12 While Büttner included the manuscripts contributed by Sulaiman and Amur in his 2-volume work on Swahili literature titled; Anthologie aus der Suaheli-litteratur (1894), the rest of the manuscripts he included from other African authors remained uncredited.13 His successor; Carl Velten, also reproduced works written by Swahili authors, only some of which he credited to their African authors.14

The abovementioned African founders had a lasting impact on the emergence and development of African studies in late 19th century Germany, which was at the time the leading center of African studies in Europe (France’s ‘Bureau of Colonial Ethnography’ opened in 1907 while the UK’s SOAS University opened in 1916). In the succeeding years, dozens of African lecturers would travel to Berlin and Hamburg, where they contributed greatly to the creation of the so-called ‘colonial library’ —which was in truth a body of knowledge produced by Africans but subsumed by imperial interests15.

Swahili lecturer at the SOL in Berlin, ca. 1911, collection of Carl Velten & Alice Carnwath. Rooftop view of Zanzibar, Tanzania, ca. 1936, Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek.

Many of the experiences of African lecturers in early 20th century Germany resembled those of their predecessors. Examples include the Duala scholar Peter Mukuri Makembe, who arrived in Germany from Cameroon in 1910 and later traveled to Hamburg in 1913 to collaborate with Carl Meinhof. However, after about four years, the relationship between the two soured when Makembe felt that he was not given recognition in Meinhof’s book on the Duala language. This resulted in Makembe leaving the institute in 1917 to pursue his own interests.16

The tenuous relationship between the African intellectuals and their European colleagues explains why most of the pioneering studies written by African scholars about their own societies remained largely unknown. Fortunately, recent efforts to decolonize African studies have begun to uncover the contributions of hidden African founders such as Imam Umaru, as well as a lesser-known East African scholar named Mtoro bin Mwinyi Bakari (1869-1927).

Mtoro traveled from the city of Bagamoyo (in Tanzania) to Berlin in June 1900, and served as a lecturer at the SOL until 1905 and at Hamburg from 1909-1913, after which he returned to Berlin where he settled, married, and lived the rest of his life. In 1903, Mtoro completed an anthropological work on the Swahili, Zaramo, and Nyamwezi of central Tanzania titled ‘Desturi za Wasuaheli’. This work was written in Swahili using the Arabic script, before it was translated into German by Carl Velten and published.

In its very short preface, Velten presents the book as a compilation of reports, for which Mtoro only served to ‘point him in the right direction’.17

However, a more recent reexamination and translation of the original Swahili manuscript in 1981 has shown that the bulk of the 210-page book was written by Mtoro himself, and that rather than being a mere collection of reports, the Swahili author “worked over the whole book and gave to it homogeneity and distinction of style.”18

My latest Patreon article explores the life and works of Mtoro Bakari, including excerpts from his study of East African societies.

please subscribe to read about it here:

Gorgoryos and Ludolf : The Ethiopian and German Fore-Fathers of Ethiopian Studies An Ethiopian scholar’s 1652 visit to Thuringia* by Wolbert G.C. Smidt

A New History of Ethiopia: Being a Full and Accurate Description of the Kingdom of Abessinia. by Hiob Ludolf, 2nd edition published by Samuel Smith, 1684.

Nineteenth Century Hausaland Being a Description by Imam Imoru of the Land, Economy, and Society of His People by Douglas Edwin Ferguson pg 1-2.

Nineteenth Century Hausaland Being a Description by Imam Imoru of the Land, Economy, and Society of His People by Douglas Edwin Ferguson pg 3-4.

Ordering Africa: Anthropology, European Imperialism and the Politics of Knowledge by Helen L. Tilley, Robert J. Gordon pg 71-78

this is the primary theme of the book; Ordering Africa: Anthropology, European Imperialism and the Politics of Knowledge by Helen L. Tilley, Robert J. Gordon.

Ordering Africa: Anthropology, European Imperialism and the Politics of Knowledge by Helen L. Tilley, Robert J. Gordon. pg 119-130

Africa in Translation: A History of Colonial Linguistics in Germany and Beyond, 1814-1945 by Sara Pugach pg 74-86, 141-142

Africa in Translation: A History of Colonial Linguistics in Germany and Beyond, 1814-1945 by Sara Pugach pg 153-154

Mtoro bin Mwinyi Bakari: Swahili Lecturer and Author in Germany By Ludger Wimmelbücker pg 31-33

Islam in German East Africa, 1885–1918: A Genealogy of Colonial Religion By Jörg Haustein pg 78-79.

Mtoro bin Mwinyi Bakari: Swahili Lecturer and Author in Germany By Ludger Wimmelbücker pg 33-34

The Customs of the Swahili People by Mtoro bin Mwinyi Bakari (Trans. By J. W. T. Allen) pg x-xi.

Sultan, Caliph and the Renewer of the Faith: Ahmad Lobbo, the Tarikh al-fattash and the Making of an Islamic State in West Africa by Mauro Nobili pg 25-27

Black Germany: The Making and Unmaking of a Diaspora Community, 1884-1960 By Robbie Aitken, Eve Rosenhaft pg 134

Desturi za Wasuaḥeli na khabari za desturi za sheriʻa za Wasuaḥeli, [gesammelt] By Carl Velten, published by Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1903, pg v.

The Customs of the Swahili People by Mtoro bin Mwinyi Bakari (Trans. By J. W. T. Allen) pg vii

Fascinating. A colleague once flippantly said "you Africans dont document your own history". Now I want to revisit that conversation.

Thank you for this meticulous research.