The Luba kingdom and the divergent fortunes of pre-colonial Central Africa (1750-1870).

The connections between pre-colonial Central African kingdoms and the expansion of international trade during the 19th century feature prominently in debates about African agency and dependency.

The Luba kingdom, which established hegemonic control over large parts of what is today southeastern D.R.Congo between the 18th and 19th centuries, represents one of the best case studies for the divergent fortunes of pre-colonial societies during the age of long-distance caravan trade.

In the first half of the 19th century, Luba kings and their clients doubled the territorial extent of their kingdom over a mosaic of smaller societies between the Congo River tributaries and the shores of Lake Tanganyika. But during the 1870s and 1880s, the kingdom disintegrated under the impact of a protracted internal succession dispute, and the intrusion of well-armed traders from the East African coast and Angola.

This article explores the history of the Luba kingdom and the significance of its collapse to the historiography of international trade in 19th-century central Africa.

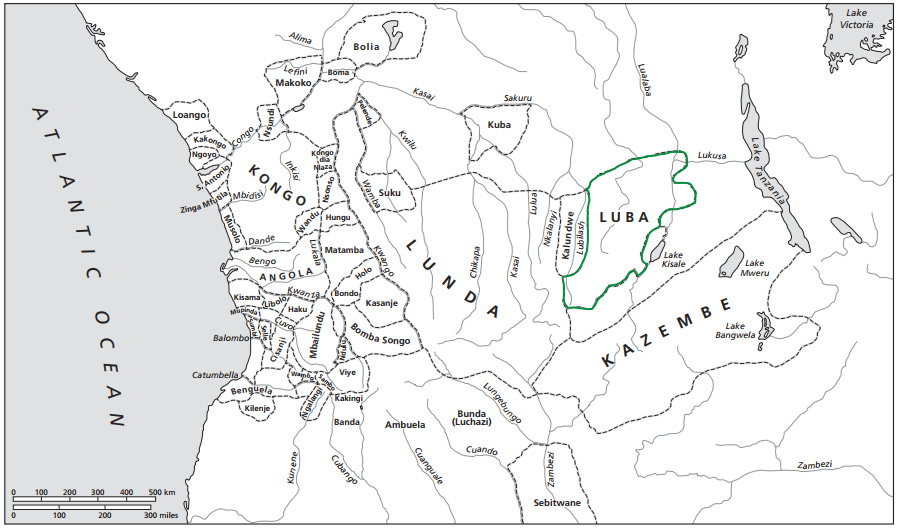

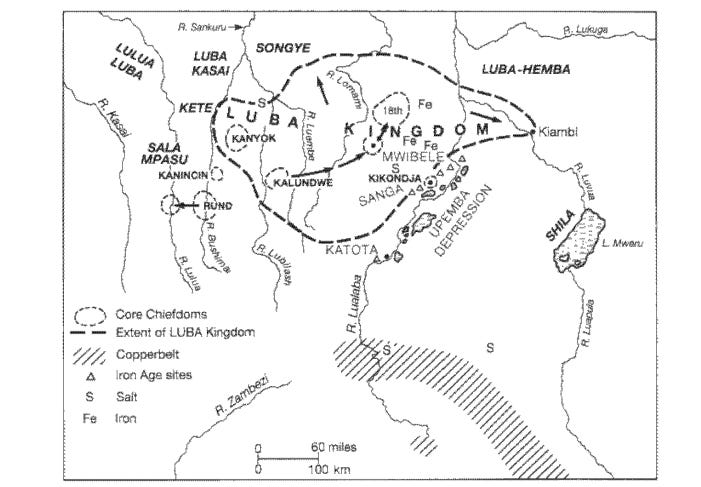

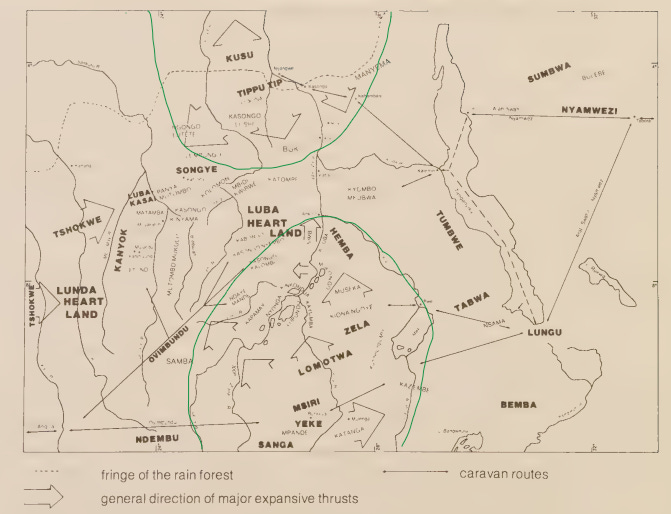

Map showing the kingdoms of west-central Africa in 18501

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The pre-history of the Luba

The Luba state emerged in the Upemba depression of what is today south-eastern DR Congo during the 18th century. Before the emergence of the kingdom, the Upemba region was home to several complex Iron-Age societies dating back to the mid-1st millennium CE, with hierarchical societies emerging by the end of the 1st millennium.2

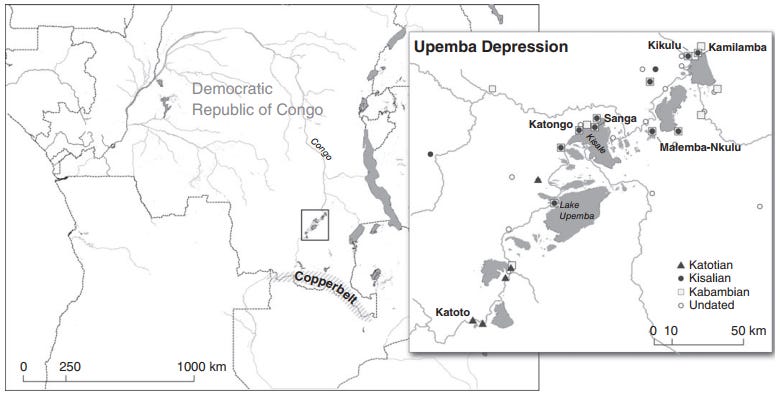

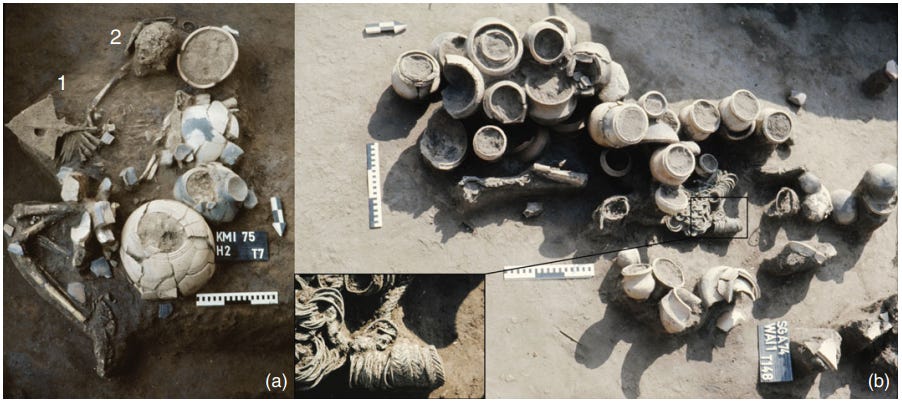

Excavations of various settlement sites and burials uncovered a trove of grave goods that included iron weapons, agricultural tools, and jewellery belonging to the Kamilambian tradition (550-750 CE), the Kisalian tradition (750-1300 CE), the Kabambian tradition (1300-1750 CE) and the Luba period (1750-1900 CE). The excavations uncovered almost three hundred graves, one of the largest sets of burials studied south of the Sahara.3

Location of the Upemba Depression and archaeological sites, and distribution of archaeological cultures. Image by Nicolas Nikis

Copper objects, which first appeared in the 8th century, became more abundant in the early 2nd millennium CE, in the form of ornaments and cross-shaped ingots that were used as currency. The large amount of copper in circulation during the Classic Kisalian (900-1300 CE) indicates intensive trade with the Copperbelt 200 km to the south (see map above). Trade with the East African coast, which began during this period as evidenced by the presence of cowrie shells, intensified in the later period known as the Kabambian (1300-1750 CE), as shown by the extensive finds of glass beads.4

The craftsmanship of Kisalian iron, copper, ivory, bone, and pottery indicates the presence of professional artisans. Marked social stratification is observed as early as the 8th century, evident in the existence of ceremonial axes with handles decorated with nails, much like those found recently among the Luba as symbols of authority.5

Two Kisalian graves. (a) Adult, buried with a ceremonial axe (1) and an iron anvil (2), Ancient Kisalian, Burial 5, Kamilamba. (b) Two child graves, with a detail of the 2.5 kilograms of copper ornaments found in one of them, classic Kisalian. images and captions by Nicolas Nikis

The early Luba kingdom

The early history of the Luba polity is entwined with the emergence of the neighbouring Lunda kingdom (first documented in 1680), whose traditional accounts are broadly similar.

Central to these accounts is the arrival of a group of hunters led by a certain Kalundu, who founded a state called simply “Luba” and a ruling dynasty. The last potentate of the great dynasty was called Mutombo Mukulu, ruler of a country called Kalundwe, and, seeing his great kingdom weakening, advised his sons, Kasongo, Kanyoka, Ilunga, and Mai, to leave him, so they “went to obtain new lands,” going upstream on the rivers and “constituting new states.”6

According to the Luba epic, the founding king was Nkongolo Mwamba, a cruel despot who is symbolically recalled as ‘red-skinned’. Nkongolo's authority was challenged by a ‘black’ hunter named Mbidi Kiluwe, who came from the east of the Congo River. The union of Mbidi Kiluwe with one of Nkongolo's sisters produces a ‘black’ prince named Kalala Ilunga, who grows to become a heroic warrior. Kalala later defeated Nkongolo’s army using the help of the god Mijibu Kalenga and ascended to the throne as Mwine Munza - the first Luba king.7

Like most foundation myths, the Luba epic wasn't a literal record of past events, but a political charter that legitimizes the ruling dynasty and the kingdom's institutions.8 Political power in the Luba kingdom was dispersed over “a multi-centered constellation of chieftaincies, officeholders, societies, and solidarities that validated each other’s claims to power” in relation to a semi-mythical center.9

In these dispersed centers of power was a lively court tradition where the kingdom's political and cultural institutions were created and where the royal history was preserved. Luba elites created a rich visual vocabulary for expressing concepts of memory, and for encoding and stimulating mnemonic processes using memory boards, beaded headdresses and necklaces, thrones, figures, and staffs.10

[Luba historical traditions were preserved by the Mbudye secret society using memory boards known as the Lukasa, which I explore in greater detail in this Patreon essay.]

memory board, Luba, D.R.C, ca. 19th-20th century, Brooklyn museum

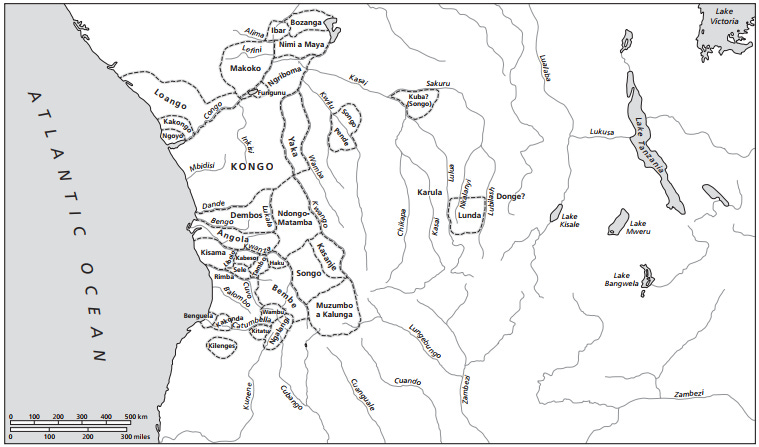

The Portuguese chronicler Cadornega, who briefly refers to the early Lunda kingdom in 1680, based on accounts obtained from cloth traders from Kassanje (in Angola) who visited the interior, also mentions a powerful group, known as the “Donges,” who had routed the armies of Lunda's vassals. The historian John Thornton suggests that the ‘Donges’ were the Kassanje term for Luba-speakers. 11

The Luba later appear more accurately in the 1756 account of the diplomat Correia Leitão, who mentions that the Lunda king Kasong had defeated the “Só-Sós, Quiacas, quilubas”, who are identified as the western Luba-speakers of Nsonso and Yaka. But traditions also mention that Kasong later died in the war against these Luba polities, which remained the main threat to Lunda's northern expansion into the textile belt, before the emergence of a hegemonic Lunda kingdom under the successors of King Kalala.12

Map of West Central Africa in 1650 showing the early Lunda kingdom and the ‘Donge’. Map by J. K. Thornton.

The early Luba kingdom around 1700, map by J. Vansina

Initially, the kingdom established in the Upemba depression was a small polity that challenged the pre-existing Luba-speaking states of Kalundwe and Kikondja. The kingdom gradually expanded throughout the 18th century, during the generations of Kings Ndaye Mwine Nkombe and Kadilo, ca. 1690-1750, and Kekenya (r. 1750-1780), all of whom frequently moved their royal courts to better exploit the tribute resources of the region.13

Kekenya was succeeded by the King Ilunga Sungu (r. 1780-1810), who grew the Luba state into an Empire, and is credited with consolidating control over the central Luba regions through appointing clients known as ‘fire’ kings (balopwe wa mudilo), who were given the ashes of a Luba monarch as a signifier of their noble status. He also launched serious military efforts against the neighbouring kingdom of Kanyok in the west and the Hemba polities in the east, but with mixed results. The Luba state achieved its greatest extent during his reign, becoming a major rival of the Lunda empire.14

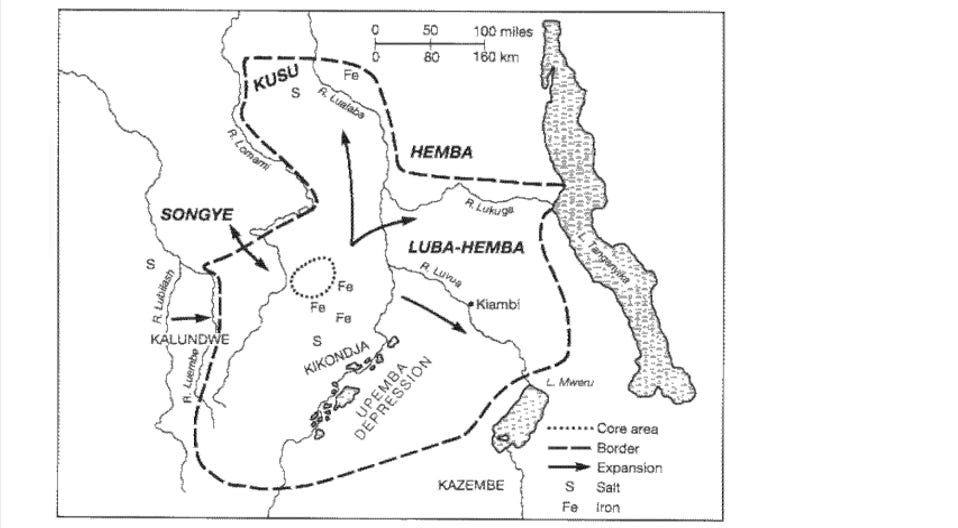

The Luba kingdom in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, map by J. Vansina

Organisation of the Luba Empire and the early period of international trade.

In the complex social-political organization of the Luba state, the king was assisted by titled officials and a secret society known as the Bambudye. The latter was the principal branch of the Luba royal culture since all royals and chiefs were initiates. It was tasked with preserving the history of the kingdom and spreading royal propaganda to outlying areas about the prestige and sanctity of Luba kingship. It also acted as a counterforce to the king’s power and that of subordinate political leaders since initiates of the society did not recognize kinship ties but only bonds of clientship created through the exchange of goods and services.15

The central administration supervised the collection of tribute, organized the military, and advised the king through the tshidie (general council) and the tshihangu (court). The titled officials collected tribute in the form of corvée labour and milambu (taxes) and in gifts paid at the investiture of Kugala (dignitaries). Territorial administration was in the hands of the bilolo, each responsible for a kibwindji (region), and normally chosen by the local people from amongst the ruling family of the district and confirmed by the court.16

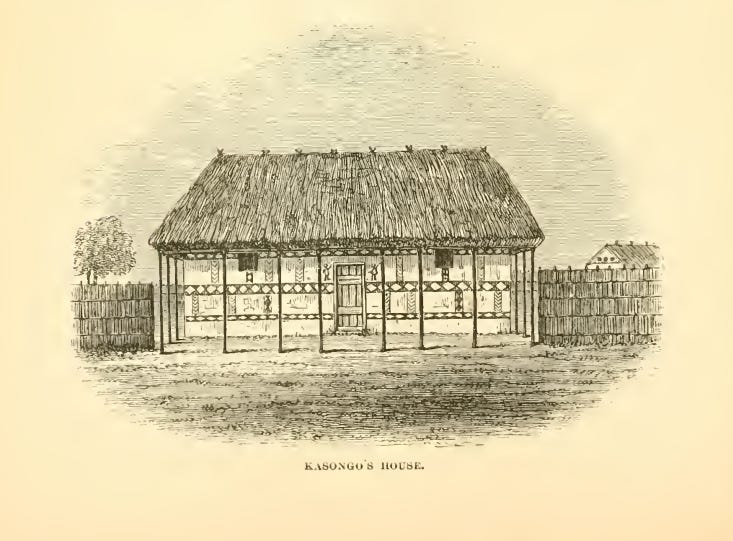

One of the residences of Luba ruler Kasongo Kalombo, Illustration from Across Africa by Verney Lovett Cameron, 1877. These images were made after the kingdom’s disintegration.

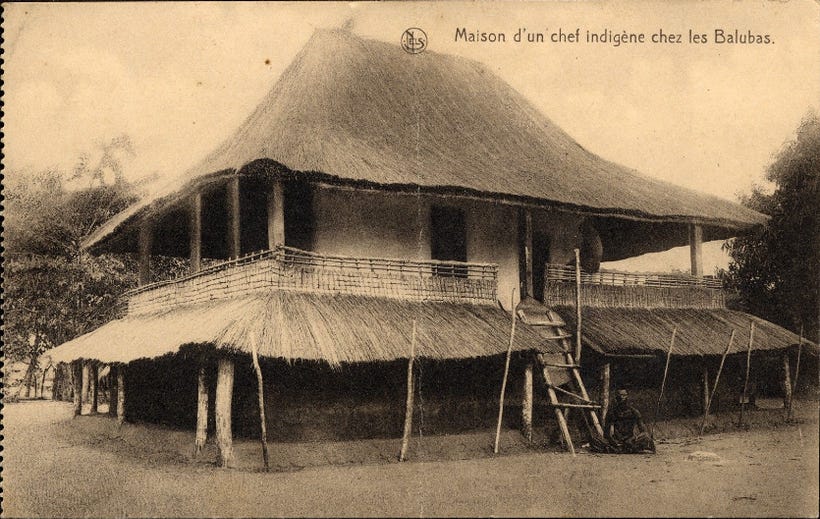

House of a Luba chief, Congo, ca. 1920-1940.

In the first half of the 19th century, dynastic ambitions and economic conditions brought the largest kingdoms of central Africa into direct competition with one another.

The Lumba king Kumwimbe Ngombe (r. 1810-1840) is the first to have been mentioned in contemporary written records. The Portuguese envoy Antonio Gamitto, who visited the court of the kingdom of Kazembe (a Lunda province southeast of Luba), provided a lengthy report on the visit of envoys of Kumwimbe Ngombe to the Kazembe king in 1832. King Kumwimbe's armies were campaigning southward along the border with Kazembe, and later led a failed invasion of the Kazembe capital itself, ostensibly to access long-distance trade routes blocked by the Kazembe kings, but more likely as a culmination of Luba’s expansionism.17

According to the accounts of David Livingstone and Cameron, who traversed the region during the 1850s and 70s, respectively, the Lunda and Luba prevented long-distance traders from visiting rival capitals, with the Luba blocking traders from the East African coast, while the Lunda blocked those from Angola. Written accounts by the Ovimbundu traders from Angola, and Portuguese envoys from Mozambique who visited Kazembe’s court in the early 19th century indicate that the province had since thrown off its suzerainty to the Lunda emperor and was also blocking merchants from traveling beyond its domains.18

The primary items of long-distance trade in the Luba heartland were copper, cloth, salt, and later, captives. Copper was traded northward from the copperbelt since the late Middle Ages. Hundreds of copper crosses have been found in graves filled with Kabambian pottery (14th-18th century), and skeletons have been uncovered that were clutching small crosses in their hands. Like in other parts of central Africa's textile belt, quantities of raphia-cloth strips had a specified value in relationship to commodities exchanged, along with salt blocks and iron tools.19

The East African coastal trader Tippu Tip, who reached the northern part of the Upemba region in 1872, reported:

“Here everyone meets together from all the districts of URua [Luba land]. Some brought goods, others beads and bracelets, still others brought goats and slaves, and Viramba, cloth of raffia... in strips six to nine inches long. Others travel as far as Irandi [Ilande, southern Songye], the place where they make the Viramba—this cloth in strips. They’re great traders, these WaRua [baLuba]!”20

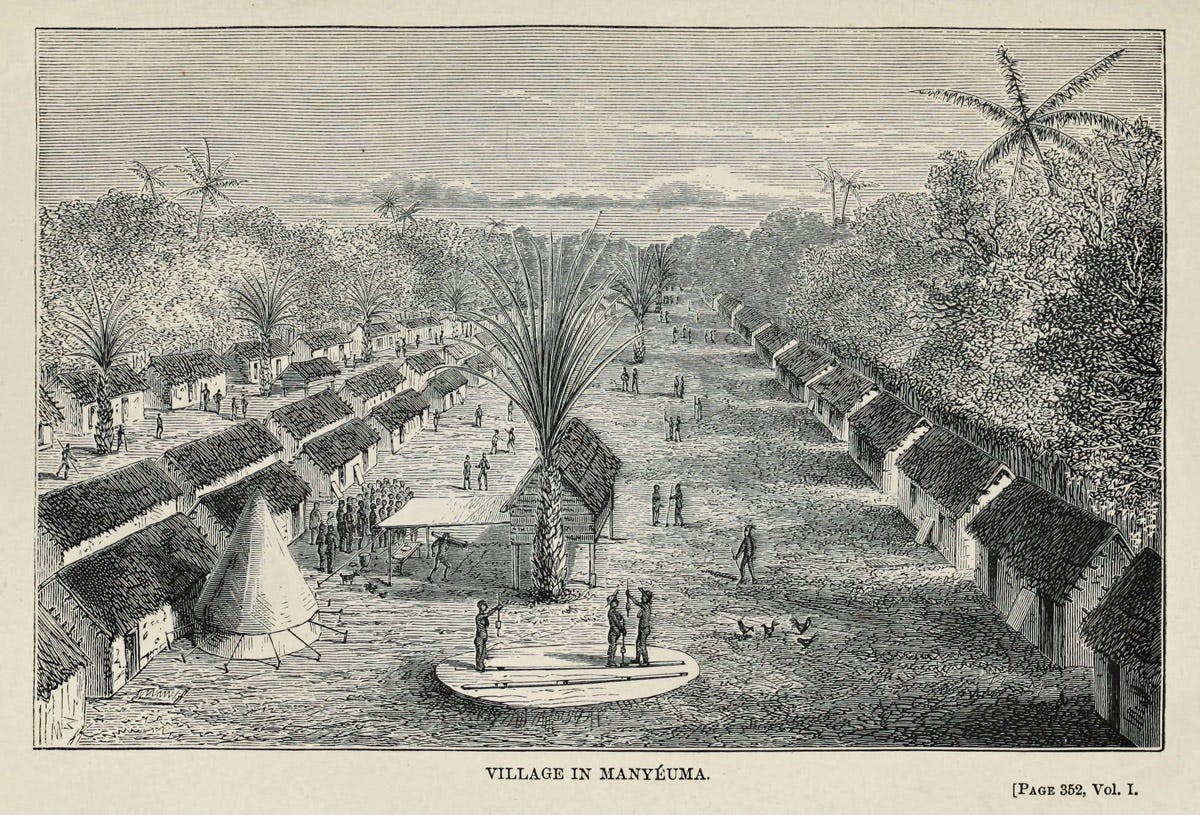

Village in Manyéuma (Manyema/Maniema), Congo. Illustration from Across Africa by Verney Lovett Cameron, 1877. Manyema came under the control of Luba clients during the reign of Ilunga Kabale, as mentioned in Tippu Tip’s account, and Luba traders could be found in its markets according to Livingstone.

Collapse of the Luba kingdom.

In the middle of the 19th century, Central Africa had become a commercial crossroads: the meeting point of two converging frontiers of long-distance trade, anchored in the coastal towns of East Africa on one hand and Angola on the other.

During this period of growing interstate competition and long-distance exchanges, Luba hegemony was maintained by the long reign of Ilunga Kabale (r.1840-1870), who stabilized and briefly extended the borders of the empire. The expansion of Luba's client states eastwards to the Manyema region near Lake Tanganyika at Nyangwe, was likely driven by the availability of local tribute sources, complemented by long-distance trade in ivory, noted in Livingstone's account.21

However, a protracted succession crisis followed the death of Ilunga Kabale, with his son Kasongo Kalombo (r. 1870-1886) emerging as one of the most powerful of several rivalling princes.

Hoping to gain leverage over his rivals, Kasongo allied himself with the East African ivory trader Juma Merikani, who moved his base of operations to Kasongo's domains by 1874, allowing Kasongo to obtain firearms in exchange for ivory. Most of these East African traders operated small caravans and were beholden to their hosts for security and provisions, but large caravans were not dependent on local rulers for either. So when Kasongo detained Juma's caravan in 1885, the latter sent a message to Tippu Tip, who threatened to attack Kasongo.22

During the last decades of the 19th century, powerful merchant-kings like Tippu Tip and Msiri began chipping away at Luba’s client states. Msiri, a Sumbwa trader from northwestern Tanzania, established a conquest state along the southeastern frontier of the Empire. Tippu Tip, on the other hand, moved to the Luba territory controlled by Kasongo Lushi in 1874, where he claimed to be one of the princes, and thus insinuated himself into state affairs by building a network of client states, including among the Songye that were previously under the Luba.23

Outline of the kingdoms established by Msiri and Tippu Tip in Luba territory. Map by Thomas O. Reefe

In the ensuing period, competing sets of alliances were formed between the rivaling factions within the Luba heartland, kick-starting a period of social and political upheaval that resulted in the kingdom's disintegration. The devastation of the Luba heartland was worsened by the arrival of the Ovimbundu from Angola, who severed the tribute system of the remaining provinces in the west, and attacked the now poorly defended settlements of the Luba. The Luba state ceased to exist, and dynastic conflict between the rival successors would continue into the 20th century.24

By the 1880s, the Luba kingdom had effectively collapsed, as power shifted to the new capitals of the kingdoms established by Msiri and Tippu Tip at Bunkeya and Kasongo, respectively. The succession dispute following the death of King Ilunga Kabale was never resolved and remained contested between his last two surviving sons, Kasongo Nyembo and Kumwimbe Tshimbu, who formed rival branches.

The arrival of the Belgian colonial armies in the Luba region in 1893 did not mark the end of this period of social upheaval, as warlords like Tippu Tip were retained by the colonial administration, despite Belgian claims that the colonization of Congo was an anti-slavery venture. While the Luba escaped the more brutal atrocities suffered by those living in the rubber-producing regions, in 1895, a section of the soldiers of King Leopold’s Force Publique mutinied and raided the Luba heartland from 1897 to 1901, before their revolt was brutally crushed. Not long after this, one of the claimants, Kasongo Nyembo, would lead a rebellion against the Belgians that lasted from 1905-1917.25

Conclusion: On the diverging fortunes of central African kingdoms at the eve of colonialism

The collapse of the Luba kingdom reveals the internal divergence within African societies during the age of long-distance caravan trade.

Many of the more powerful kingdoms and societies of the Great Lakes region and central Tanzania, such as Buganda, Karagwe, Nyamwezi, and Ugogo, which could impose taxes on passing merchants, provide porters for hire, and determine the terms of trade, exploited the long-distance trade to their advantage.

At the same time when networks of political and economic clients were becoming unstable and precarious in the Luba heartland, powerful rulers like Mutesa (Buganda) Mirambo, and Nyungu ya Mawe (Nyamwezi) were using their newly acquired wealth and firearms to expand their influence over not just neighbouring states, but also the caravan towns like Tabora and Ujiji, which remained at the mercy of local potentates, rather than transforming into new centers of power like Msiri and Tippu Tip’s capitals had become.26

Even acephalous societies in central Tanzania could extract high taxes from passing caravans and routinely attacked those who didn’t comply, as outlined in the 19th-century travel account of the Swahili trader Mwenyi Chande. The sort of protection racket run by Tippu Tip in south-eastern Congo was non-existent in Ugogo country, where Mwenyi Chande’s caravan was forced to pay high taxes to the local chief at Msanga named Mabokera, in exchange for provisions which the chief never remitted.

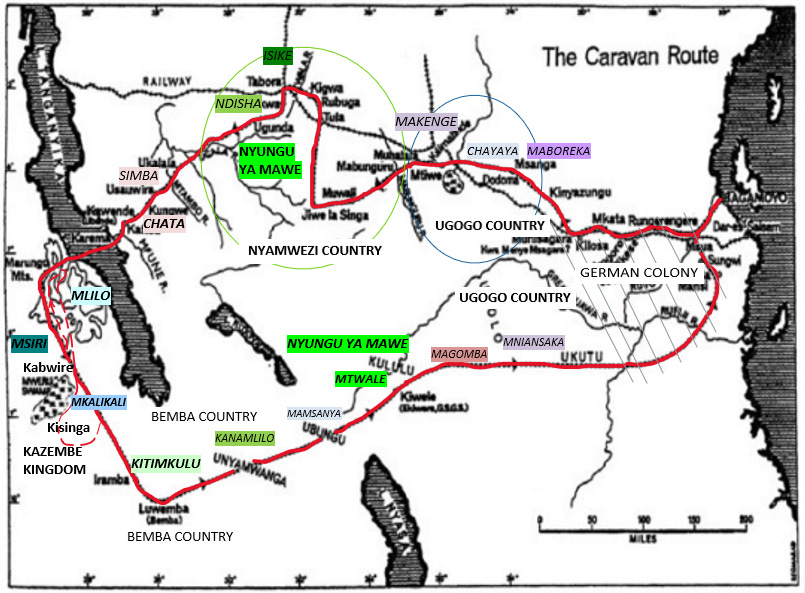

Map showing the caravan route of Mwenyi Chande in 1891, including a few of the kings he encountered. (This is only a very brief summary since Mwenyi Chande mentions at least 80 different rulers)

In northern Angola, the Ovimbundu traders who were the antagonists in the story of Luba's collapse facilitated the economic revival of the region during the age of legitimate commerce, as rulers of kingdoms like Kongo could extract high taxes from passing merchants and control their activities, despite the kingdom being in the throes of decline as well.

The divergent fortunes of the Luba and neighboring kingdoms in south-eastern Congo during the late 19th century, therefore, stand in stark contrast to the relative economic prosperity of other parts of Central Africa. The reasons for the kingdom’s disintegration must be sought in the internal weaknesses that were accentuated and exploited by ambitious merchants, resulting in the social upheavals of the region during the late 19th century that would invariably shape the politics of the modern D.R.C. during the colonial and post-independence periods.

Throughout the 19th century, Africans who had extended contacts with the industrializing Western world began recognizing the need to modernize quickly if they were to retain their autonomy. In the kingdom of Kongo, an intellectual conflict emerged between the Western-educated nationalists and the traditional rulers that would define the competing visions of modernizers and traditionalists on the eve of colonialism.

Please subscribe to read more about it here, and support this newsletter:

Map by J.K. Thornton

The Rainbow and the Kings: A History of the Luba Empire to 1891 By Thomas O. Reefe, pg 67-72

“Upemba Depression.” by Nicolas Nikis In The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, edited by D. T. Potts

Luba Roots: The First Complete Iron Age Sequence in Zaire by Pierre de Maret, pg 233

Luba Roots: The First Complete Iron Age Sequence in Zaire by Pierre de Maret, pg 233-234)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 By John K. Thornton 146-147

The Rainbow and the Kings: A History of the Luba Empire to 1891 By Thomas O. Reefe pg 24-30)

The Rainbow and the Kings: A History of the Luba Empire to 1891 By Thomas O. Reefe pg 62-63)

Memory: Luba Art and the Making of History by Mary Nooter Roberts and Allen F. Roberts, pg 25, Cambridge History of Africa. Vol 4, pg 377-378

Memory: Luba Art and the Making of History by Mary Nooter Roberts and Allen F. Roberts

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 By John K. Thornton, pg 147-148)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 By John K. Thornton, pg 219-236)

Unesco Vol 5, Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century, pg 595-599, The Rainbow and the Kings: A History of the Luba Empire to 1891 By Thomas O. Reefe, pg 110-114)

The Rainbow and the Kings: A History of the Luba Empire to 1891 By Thomas O. Reefe, pg 118-128, Cambridge History of Africa. Vol 5 pg 250-251

The Rainbow and the Kings: A History of the Luba Empire to 1891 By Thomas O. Reefe, pg 45-48

Unesco Vol 5, Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century, pg 595-599)

The Rainbow and the Kings: A History of the Luba Empire to 1891 By Thomas O. Reefe, pg 138-142)

The Rainbow and the Kings: A History of the Luba Empire to 1891 By Thomas O. Reefe, pg 120, A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John K. Thornton pg 270-271, 320-321)

The Rainbow and the Kings: A History of the Luba Empire to 1891 By Thomas O. Reefe, pg 93-95

The Rainbow and the Kings: A History of the Luba Empire to 1891 By Thomas O. Reefe, pg 97)

The Rainbow and the Kings: A History of the Luba Empire to 1891 By Thomas O. Reefe, pg 146-151)

The Rainbow and the Kings: A History of the Luba Empire to 1891 By Thomas O. Reefe, pg 164-165, 184-186, Church, State and Colonialism in Southeastern Congo, 1890–1962 By Reuben A. Loffman pg 44-47. on the dynamics of East African caravan trade and its effects, see; Carriers of culture by Stephen J. Rockel

The Rainbow and the Kings: A History of the Luba Empire to 1891 By Thomas O. Reefe, pg 165-167, 172-180

The Rainbow and the Kings: A History of the Luba Empire to 1891 By Thomas O. Reefe, pg 188-191)

The Rainbow and the Kings: A History of the Luba Empire to 1891 By Thomas O. Reefe, pg 192-193, Church, State and Colonialism in Southeastern Congo, 1890–1962 By Reuben A. Loffman pg 86-89

UNESCO General History of Africa Vol. 6, pg 244-254, For an excellent overview of the effects of long-distance trade see; Carriers of culture : Labor on the Road in Nineteenth-Century East Africa by Stephen J. Rockel

Thank you for your tireless work

Interesting architecture that blended seamlessly with nature, but quite revealing was the Black Red dichotomy in the kingdom wasn't expecting that, also these are the people destroyed by the Swahili trader/enslaver Tippu Tib who opened up the continent to European colonization, which peaked in the heart of Darkness of Leopold of Belgium.