The myth of Mansa Musa's enslaved entourage

"Stories about his [Mansa Musa's] journey have numerous anecdotes which are not true and which the mind refuses to admit".

The pilgrimage of Mansa Musa in 1324 is undoubtedly the most famous and most studied event in the history of the west-African middle ages. The ruler of the Mali empire has recently become a recognized figure in global history, in large part due to recent estimates that was the wealthiest man in history. Thanks to the abundance of accounts regarding his reign, Musa has become a symbol of a prosperous and independent Africa actively participating in world affairs, leaving an indelible mark not just on European atlases, but also in the memories and writings of West Africa.

But as is often common with any interest in Africa’s past, there's a growing chorus of claims that Mansa Musa was escorted by thousands of enslaved people to Egypt, which would make him one of the largest slave owners of his time. While many who make these claims don't ground them in medieval accounts of Musa's pilgrimage, they have found some support in the book 'African dominion' written by the west-Africanist Michael Gomez, who asserts that the Mansa travelled with an entourage of 60,000 mostly enslaved persons.

However, other specialists in west African history such as John Hunwick find these numbers to be rather absurd, arguing that they were inflated in different accounts and were based on unreliable sources. Indeed, the multiplicity of historical accounts regarding Musa's pilgrimage seem to have favored the emergence of dissonant versions of the same event, which were eventually standardized over time.

This article outlines the various accounts on Mansa Musa's entourage, inorder to uncover whether the Malian ruler was the largest slave owner of his time or he was simply the subject of an elaborately fabricated story.

Detail from the 14th century Catalan Atlas showing Mansa Musa

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more on African history and keep this newsletter free for all:

The Limits of west-African sources on Mansa Musa.

Most claims that Mansa Musa was followed by a large entourage of slaves rely on the west African chronicle titled Tarikh al-Sudan, written by a scholar named Abd al-Rahman Al-sa'di in 1655. Al-Sa'di's chronicle was one of three important 17th century west African manuscripts —the others being; the Tarikh al-Fattash and the Notice Historique— which modern historians call the Timbuktu chronicles.

The Timbuktu chronicles were written not long after the fall of Mali’s sucessor; the Songhai empire, by scholars whose families were prominent during its heyday. In their desire to construct a coherent and legitimating narrative of the ‘western Sudan’ (an area encompassing modern Mali to Senegal), the chroniclers offer a special place to the Mali empire. They include details on both the former empire which had fallen to the Askiya dynasty of Songhai, as well as the contemporaneous state which was at almost constant war with Songhai before the latter’s collapse. 1

As some of the oldest internal sources written by west Africans about their own history, modern historians had long considered them to be more reliable reconstructions of the region’s past compared to external accounts written outside the region.

However, specialists on west African history have recently acknowledged the limitations of the Timbuktu chronicles and their authors regarding the earlier periods of the region's history. The historian Paulo de Moraes Farias, who uncovered a number of inscribed stelae from the medieval city of Gao from which the Askiya title and the first Muslim west-African rulers are first attested, has shown that Al-Sa'di was not aware of Gao significance but dismissed it as a center of 'undiluted paganism'. Cautioning modern historians, Paulo de Moraes writes that:

"They (the Timbuktu chroniclers) were not mere informants but historians like ourselves, and they had their own difficulties in retrieving evidence and reconstructing the past from the point of view of their novel intellectual and political stance".2

Commemorative Stela of a King and Queen from Gao, Mali, dated to the 12th century, first one is at the Musée national du Mali, second one is at Institut Fondamental d’Afrique Noire Cheikh Anta Diop, Dakar, Senegal

The old city of Gao in 1920, archives nationales d'outre mer

Similary, the historian Mauro Nobili has shown that the Tarikh al-Fattash was mostly a 19th century chronicle that utilised information from two 17th century chronicles; Tarikh Ibn al-Mukhtar of the west African chronicler Ibn al-Mukhtar and the Tarikh al-Sudan of Al-Sa’di . He also argues that the Timbuktu chronicles were not mere repositories of hard facts waiting to be mined by modern historians, but were, like all historical documents, carefully crafted reconstructions of the past that were heavily influenced by their authors' social and political context.3

The Timbuktu chroniclers, like all historians past and present, were themselves aware of the limitations of their sources, with one Timbuktu chronicler for example, mentioning that there were no internal documents on the Kayamagha dynasty of the Ghana empire.4

This limitation of textural sources wasn't alleviated by the oral sources available to the Timbutku historians. For example, Ibn al-Mukhtar's chronicle, which was written in 1664, includes many anecdotes about Mansa Musa derived from oral accounts, but he also relayed the fact that there were a significant number of stories said about Mansa Musa's pilgrimage that seemed fabricated, warning his readers that;

"Stories about his [Mansa Musa's] journey have numerous anecdotes which are not true and which the mind refuses to admit".

He adds that "Among these, the fact that every time he was in a town on Friday on his way here towards Egypt, he did not fail to build a mosque there the same day" Others include having his servants dig a pool for his wife in the middle of the desert, and one of his scouts descended into a well to capture a highway robber who was cutting the buckets from the ropes that they were lowering into the well, so that Musa’s carravan couldn’t draw water.5

Even though such stories were evidently exaggerated and fabricated, the anecdotes about Mansa Musa's pilgrimage show that the era of the Mali empire was a turning point in the Islamic and imperial identity of the western Sudan —an identity which the Timbuktu writers were furthering despite their objections to the unreliability of their sources.

Besides internal accounts, the Timbuktu chroniclers also utilized external sources from the “East”, especially those coming from Mamluk Egypt and Morocco. In his account of Mansa Musa’s pilgrimage for example, al-Sa'di specifically mentions his source to be Ibn Battuta's Riḥla (Travels) which contains a section on the famous globe-trotter's stay in Mali from 1352-1353. However, al-Sa'di only used Ibn Battuta as a source regarding a short anecdote on the place Musa stayed while he was in Cairo, but other details about Musa's entourage were clearly derived from another unamed source since Ibn Battuta makes no mention of Musa's companions besides naming several 'black Hajjis' who accompanied their sovereign to Mecca.6

We therefore turn to the so-called 'Eastern' sources to uncover the documents which the Timbuktu chroniclers used for their information on Musa's entourage.

The earliest accounts of Mansa Musa’s pilgrimage and entourage from Egypt, Syria and Mecca.

Mansa Musa’s pilgrimage route in 1324, Map by Juan Hernandez

The oldest Egyptian account of Mansa Musa's pilgrimage comes from a text by the Mamluk official Šihāb al-Nuwayrī in his Nihāyat al-arab that was written around 1331. A high administrator and controller of the financial office during the reign of Mamluk sultan Al-Malik al-Nāṣir (r. 1293 to 1341), al-Nuwayri had access to state documents and provides us with what is so far the earliest account of Musa’s arrival in Egypt and his entourage. Al-Nuwayri writes that;

"During this year [1324] King Musa, ruler of the country of Takrur, arrived in the Egyptian lands with the aim of making the pilgrimage. He went to the noble Hejaz. He returned to his country in the year 25 [1325]. His company had brought in a considerable sum of gold. Thus he had spent it all, had scattered it, had exchanged part of it for fabrics so that he needed to go into debt for a large sum to merchants and others before his journey [towards Mecca].7

This account doesn't identify the status of Musa's entourage, which he calls his ‘company’, but simply mentions that they came with a lot of gold and spent it lavishly in Egypt.

Another, much longer account about Musa's time in Egypt was written by a son of a Mamluk official named, Ibn al-Dawādārī, in his kanz al-durar, that was written around the year 1335.

"During this year [1324] the king of Takrur arrived, aspiring to the illustrious Hejaz. His name, Abū Bakr b. Mūsā. He appeared before the noble stations of the holy places of Mecca and kissed the ground. He stayed for a year in the Egyptian regions before going to Hejaz. He had with him a lot of gold, and his country is the country that grows gold … Then the king of Takrur and his companions bought all sorts of things in Cairo and Egypt. We thought their money was inexhaustible"

His account —which I have shortened for the sake of brevity, as i will most accounts mentioned below— is similar to the one of al-Nuwayri, but adds more details about Mali’s gold sources and Musa’s meeting with the Mamluk sultan. However, Al-Dawadari also doesn't describe the status of Musa's entourage, but simply refers to them as 'companions'.8

Another early account on Musa’s pilgrimage was written by the Syrian historian Šams al-Dīn al-Ḏahabī in his Duwal al-Islām, completed before 1339, but it only describes Musa's entourage in Cairo as a "large crowd". Al-Dahabi's section on Musa's pilgrimage was repeated verbatim by the Mamluk official Šihāb al-ʿUmarī in the first version of his Masālik al-Absâr, before he later wrote a more detailed account using his own sourcs in the second version of the same work that is now famous in the historiography of Musa's pilgrimage.9

In the second version of al-ʿUmarī's Masālik al-Absâr, the Mamluk official provides a more detailed account of Musa's stay in Cairo, based on interviews with officials who hosted the Malian ruler. In a very lengthy account which includes details of Musa arriving with "a hundred camel-loads of gold", and his meeting with the Mamluk sultan where both parties exchanged gifts, al-Umari writes that

"He [the Mamluk sultan] continued to send him [Mansa Musa] Turkish slaves and abundant provisions throughout his stay" and that "He had a quantity of provisions purchased for his [Mansa Musa's] companions and his suite."

Like the previous authors, al-Umari simply describes Musa's entourage as companions, and the only mention of 'slaves' in the context of Musa's pilgrimage were the "Turkish slaves” gifted to Musa by the Egyptian sultan. The first reference to slaves in Musa’s entourage appears to be the Turkish slaves gifted to him by the Egyptian ruler. Al-Umari’s account on Mansa Musa would be repeated almost verbatim by other Egyptian scholars, including Aḥmad al-Muqrī (fl. 1365) who also refered to them simply as 'companions'.10

Our next source on Mansa Musa's pilgrimage comes from the 'Holy city' of Mecca, where an exceptional eyewitness account is provided by the Meccan scholar Abd Allāh al-Yāfiʿī (d. 1367) in his Mirʾāt al-ǧinān completed some time before his death. The people of Mali arrived in the Hejaz at a time following years of unrest in Mecca, and against a backdrop of strengthening Mamluk-Egyptian control over the holy cities. There had been several conflicts over the control of the city between the Rasulid dynasty of Yemen, the Mamluks of Egypt and a few independent figures who all claimed protection over the city. Mansa Musa's carravan arrived under the protection of the Mamluks, and this is the description of his time in the Holy city that al-Yāfiʿī witnessed:

"During this year, the king of Takrūr Mūsā b. Abī Bakr b. Abī al-Aswad presented himself for the pilgrimage with thousands of his soldiers (ʿaskar) …

I add, concerning his spirit of common sense and wisdom, that I saw him while he was at the latticed window rising above the Ka'ba of the building from ribāṭ al-Ḫūzī. He had calmed his restless companions following a discord (fitna) which had arisen between them and the Turks. They had brandished, during this discord, the swords in the Sacred Mosque (al-masǧid al-ḥarām), while Musa, being in an overhanging position, had seen upon them. He had ordered them to reconsider their intention to fight showing an intense anger towards them because of this fitna. It is a sign of the superiority of his [Musa’s] intelligence because he had no place of retreat or helper apart from those of his fatherland and his people, if the broad strength of his cavalry and his infantry had come to be reduced. The king of Takrūr Mūsā returned to Egypt. The sultan clothed him in a royal robe of honor, a circular turban, a black ǧubba, and a golden sword."11

The Meccan author specifically uses "I add" and “I saw” to mark this passage out as his own eye-witness account, making his account the only primary source that retells specific events which were seen by the author.

Importantly, the description of the fitna (quarrel/discord) which he recounts provides the first rough estimate of Mansa Musa's companions, and their status. Such violent quarrels were relatively common in the Ḥaram of Mecca in the context of pilgrimages, as they often reflected political struggles over the control of the Holy cities, but this one in particular was an internal dispute between the Malians and the Mamluks (Turks). This account indicates that Mansa Musa's entourage numbering in the thousands was heavily armed, and were it not for Musa's wise intervention, this would have been added to the 7 fitnas in Mecca that were recorded in the 14th century. Al-Yāfiʿī's account would be copied verbatim by later Meccan scholars such as Taqī al-Dīn al-Fāsī (d. 1429) .12

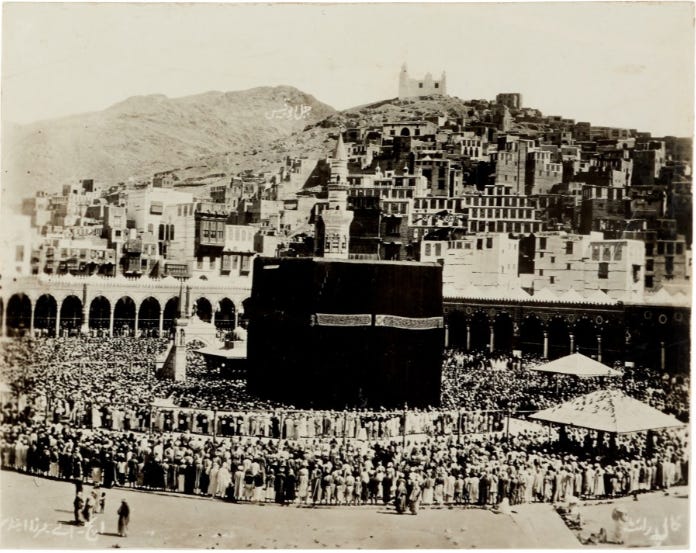

the Ka’aba at Mecca during the early 20th century

Later accounts of Musa’s pilgrimage and the first estimates of his entourage: from ‘Companions’ to ‘Maids’.

Our next source on Mansa Musa's entourage in Egypt comes from the Syrian qadi Zayn Ibn al-Wardī in his Tatimmat al-muḫtaṣar which was completed in the late 1340s. He writes that:

"King Šaraf al-Dīn Mūsā b. Abī Bakr, king of Takrūr, arrived for the pilgrimage. His company numbered more than 10,000 Takrūrī."

While he also doesn't specify the status of Musa's companions, he identifies them as Takruri, a term often used to refer to pilgrims from west-Africa when they were in Egypt and the Hejaz. It is derived from the medieval kingdom of Takrur (in modern Senegal), which was allied to the Almoravid conquerors of Andalusia (Spain). This term, which specifically marks out Musa’s entourage as pious free-born Muslims, fits well with the prestigious title of Šaraf al-Dīn (“Eminence of the faith”) that the author gave to Mansa Musa. This text also marks the first time Musa's entourage is estimated to be 10,000, an absurdly high figure that would be repeated further exaggerated in later accounts.13

Just like Al-Ḏahabī —the other Syrian historian mentioned before— Al-Wardi never met Musa and his entourage, nor did he have access to Mamluk officials or archives, but instead based his story on oral accounts and hearsay circulating in the region. This approach to collecting information on Musa’s pilgrimage was similary taken by another Syrian historian, named Ibn Kaṯīr in his 1366 work al-Bidāya wa alnihāya. The Syrian writes that

"the king of Takrur arrived in Cairo on account of the pilgrimage on the 25th of Ragab. He established his camp at Qarafa. He had with him Maghribīs (North Africans?) and servants (khadam) numbering around 20,000."14

This is the only mention of 'North Africans' in Musa's entourage which is now said to number 20,000, and it’s also the first mention of the presence of 'servants' using the specific term Kadam that usually refered to male attendants.15 However, this particular deviation is only encountered in this account, as other writers, especially those in Egypt, continue to refer to Musa's entourage as 'companions' or 'large crowds'.

These include; Zayn al-Dīn ʿUmar Ibn al-Wardī (d. 1349) who calls them a "company of 10,000 Takruri", Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn al-Ṣafadī (d. 1363) who refers to them as a “large crowd”, Badr al-Dīn (d. 1377) who refers to them as a company made up of 10,000 of his “subjects”, and the Meccan historian Taqī al-Dīn al-Fāsī (d. 1429) who refers to them as "15,000 Takārura".16

Later accounts focus more on Musa's meeting with the Mamluk sultan, without mentioning anything about his 'companions', with the exception of the Mamluk-Egyptian encyclopedist Al-Qalqašandī who in his 1412 book Ṣubḥ al-aʿšā, wrote that:

“It is said that 12,000 maids (waṣāʾif) dressed in brocade tunics carried his effects."

This specific sentence, which again begins with the characteristic 'it is said' to indicate that its based on hearsay, provides a figure not based on any previous estimate but on an attempt to reconcile different estimates of Musa's entourage. The author claims to have taken this particular estimate from the Kitab al-ʿIbar of the historian Ibn Ḫaldūn (1406), but the latter did not in fact provide any figures on Mansa Musa's companions in his section on the Malian king's pilgrimage.17

The use of the term waṣāʾif which was used for female servants in domestic contexts in Mamluk-Egypt (instead of jawārī for female slaves)18, is yet more evidence that this anecdote was simply a fabrication by Al-Qalqašandī, whose sources refered to Mansa Musa’s entourage as his “companions" who were by all indications entirely male and well-armed, and not some roving harem of medieval fantasy.

However, the brief detail on Musa acquiring servants/slaves in Egypt is again brought up by the Mamluk-Egyptian historian Al-Maqrīzī (d. 1442) in his al-Sulūk li-maʿrifat duwal almulūk, which he completed later in his life. He writes that

"He [Mansa Musa] stayed in Cairo and spent a lot of gold on the purchase of servants, clothes and other products to such an extent that the dinar fell by six dirhams"19

This passage is evidently copied directly from earlier accounts on Musa's initial stay in Cairo, specifically al-ʿUmarī’s mention of Turkish slaves sent by the Mamluk sultan, although its not implausible that Musa and his companions acquired other slaves in Egypt on their own account (as will be mentioned below).

Al-Maqrīzī later provides a more detailed account of Mansa Musa's entourage in his monograph on the pilgrimages made by Muslim sovereigns, titled al-Ḏahab al-masbūk. He writes that;

"It is said that he [Mansa Musa] came with 14,000 maids for his personal service. His companions showed consideration by purchasing Turkish and Ethiopian servants, singers and clothing."

Writing more than a century after Musa's arrival in Cairo, Al-Maqrizi seems to have taken a lot of liberties with his description of Musa's entourage. The expression "it is said that" which is followed by an inflated number of Musa's maids indicates that this passage was based on hearsay that had been exaggerated. However, this exceptional account on Musa's supposedly all-female entourage, who now included ‘Ethiopians’ wouldn't appear in later Egyptian accounts of the 15th and 16th century, such as the description of Musa's pilgrimage by al-Maqrizi's rival Badr al-Dīn al-ʿAynī (d. 1451), nor did they appear in the work of Ibn Ḥaǧar (d. 1449), nor in the work of Ibn Iyās (d. 1524).20

The disputed estimates of Musa’s entourage and their status in pre-colonial and modern western African historiography.

It was this estimate of over 10,000 companions of Mansa Musa that would be uncritically copied in later accounts, and further exaggerated to absurd proportions, that were eventually reproduced in the Timbuktu chronicles.

The Ta’rīkh al-fattāsh claims that the Mansa embarked “with great pomp and vast wealth [borne by] a huge army” numbering 8,000 people. While Ta’rīkh as-sūdān uses a much larger estimate, claiming that Musa “set off in great pomp with a large party, including 60,000 soldiers and 500 slaves, who ran in front of him as he rode. Each of the slaves bore in his hand a wand fashioned from 500 mq. of gold.”21 Its important to note that the Tarikh al-Sudan of Al-Sa’di mentions that there were only 500 slaves in the entire entourage numbering 60,000.

Some specialists on west African history who take these figures at face value, such as Michael Gomez, claim the 'disparity' between the two Timbuktu chronicles is due to Mansa Musa having begun his journey with many more followers than actually arrived with him in Cairo. Other specialists, such as John Hunwick, rightly dismiss both estimates as "grossly inflated", explaining that "logistical problems of feeding and providing water during the crossing of the Sahara rule out numbers of this order"22

Indeed the outline of external sources on Musa's entourage provided above supports Hunwick's argument that these numbers were deliberately fabricated, and this was mostly like done by different authors inorder to paint a laudatory portrait of Mansa Musa’s remarkable pilgrimage.

None of the early sources provide estimates of Musa's entourage or their exact status, with the exception of the eye-witness account from Mecca which describes them as 'thousands' of well-armed men. All accounts that include exact estimates of Musa's entourage mention that it was based on hearsay, and later accounts would add more absurd fabrications, claiming that Musa's entourage was an all-female troop of servants.

While Musa's companions did acquire 'Turkish' slaves that were brought back to Mali (and were met by Ibn Battuta), we can be certain based on the available evidence that Musa's entourage consisted almost entirely of free west African Muslims who accompanied their emperor on a journey that many of them were very familiar with. This undermines the Michael Gomez's claim that "the vast majority of the royal retinue was enslaved", an assertion that relies on him ignoring the multiple sources that specifically identify Musa's companions as west-African muslims (Takruri), to instead focus on the few sources that claim Musa entourage was made up of servants termed; waṣāʾif and khadam, both of which Gomez also mistranslates as ‘slaves’, not to mention his willful misrepresentation of Al-Sa’di’s passage which explicitly mentions that there were only 500 slaves in the 60,000 strong entourage.

Also relevant to these accounts of Musa’s entourage are the estimates of '100 camel-loads' of gold (about 12 tonnes) on which Musa's title for history's wealthiest man rests, some of which were supposedly carried by his retinue. The amount of gold itself doesn’t seem out of the ordinary if we consider that not all the gold was his, and with the exception of Al-Sa’di’s chronicle, there is no mention of people carrying this gold but only camels. Similar accounts of west African pilgrims in Egypt for example show that they were fabulously wealthy, and they often left their properties in the form of gold, luxury cloth and camels under the care of Egyptian officials for their return journey after visiting Mecca. With one pilgrim leaving behind 200 mithqals of gold and camels in 1562, while another group of six west Africans left 500 mithqals gold, cloth and several personal effects.

During his visit to Mali, Ibn Battuta met atleast four Hajjis, some of whom had accompanied Mansa Musa to Mecca, these include; Hajj Abd al-Rahman who was the royal Qadi and lived in the capital of Mali; Hajj Farba Margha who was a powerful official that lived near Mema; Hajj Farba Sulaiman who was another official that lived near Timbuktu (he also owned an Arab slave girl from Damascus presumably acquired while on pilgrimage), and Hajj Muhammad al-Wajdi who was a resident of Gao and had visited Yemen.23

Its therefore likely that many of Mansa Musa's companions were free west African Muslims, and that a significant share of the ruler’s golden treasure belonged to them.

The above outline shows that despite the abundance of accounts regarding Musa’s pilgrimage, the event was not recorded from authoritative informants but from a combination of only partially reliable sources that were inturn altered by the different interpretations of multiple writers with their own authorial intentions. A more objective account of Musa’s pilgrimage can thus only be obtained after untangling the web of fabrications and biases which colour the works of past historians as well as modern ones.

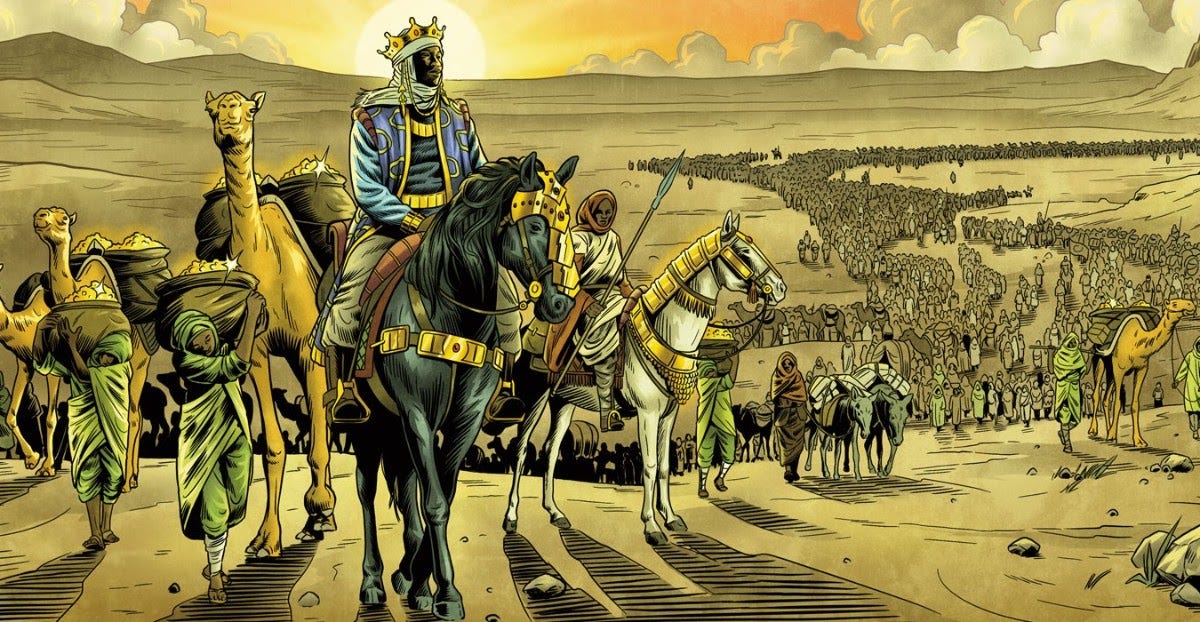

A fanciful illustration of Musa’s pilgrimage, complete with an implausibly large entourage that includes maids carrying sacks of gold

Mansa Musa’s pilgrimage was one of several occasions where Africans explored their own continent and some accounts claim he passed by the great pyramids of Giza. More than 3,000 years before Musa, people from the North-East African kingdoms of Kush and Punt also regulary travelled to and settled in ancient Egypt.

Read more about this on our Patreon:

Meanings of Timbuktu by Shamil Jeppie pg 95-98

Meanings of Timbuktu by Shamil Jeppie 98-105)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith : Aḥmad Lobbo, the Tārīkh al-fattāsh and the Making of an Islamic State in West Africa by Mauro Nobili

Meanings of Timbuktu by Shamil Jeppie pg 96)

Le sultanat du Mali - Histoire régressive d'un empire médiéval XXIe-XIVe siècle by Hadrien Collet pg 195-196)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 10 The Travels of Ibn Battuta Vol. 4 pg 967, 969)

Le sultanat du Mali - Histoire régressive d'un empire médiéval XXIe-XIVe siècle by Hadrien Collet pg 215-216)

Le sultanat du Mali - Histoire régressive d'un empire médiéval XXIe-XIVe siècle by Hadrien Collet pg 217)

Le sultanat du Mali - Histoire régressive d'un empire médiéval XXIe-XIVe siècle by Hadrien Collet pg 219-220)

Le sultanat du Mali - Histoire régressive d'un empire médiéval XXIe-XIVe siècle by Hadrien Collet pg 221-222, 226)

Échos d’Arabie. Le Pèlerinage à La Mecque de Mansa Musa by Hadrien Collet pg 115-116

Échos d’Arabie. Le Pèlerinage à La Mecque de Mansa Musa by Hadrien Collet pg pg 117-119)

Le sultanat du Mali - Histoire régressive d'un empire médiéval XXIe-XIVe siècle by Hadrien Collet pg 224-225)

Le sultanat du Mali - Histoire régressive d'un empire médiéval XXIe-XIVe siècle by Hadrien Collet pg 225-226

A Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic By Hans Wehr pg 267, The Qur'an: An Encyclopedia edited by Oliver Leaman pg 579, Race and Slavery in the Middle East by Terence Walz pg 58, Gomez himself occasionally translates the word khadam as servant in Ibn Battuta’s description of Mali’s court, African dominion by M. Gomez, pg 160

Le sultanat du Mali - Histoire régressive d'un empire médiéval XXIe-XIVe siècle by Hadrien Collet pg 224-5, 227, 229, Échos d’Arabie. Le Pèlerinage à La Mecque de Mansa Musa by Hadrien Collet pg 120)

Le sultanat du Mali - Histoire régressive d'un empire médiéval XXIe-XIVe siècle by Hadrien Collet pg 232-245) «Post-publication note: Ibn Khaldūn’s mention of 12,000 maids comes from another section of the Muqaddima, from a source which he thought not to include in his section relating to the pilgrimages of the kings of Takrur in which he makes no mention of Musa’s entourage»

Slave Trade Dynamics in Abbasid Egypt by Jelle Bruning

Le sultanat du Mali - Histoire régressive d'un empire médiéval XXIe-XIVe siècle by Hadrien Collet pg 236)

Le sultanat du Mali - Histoire régressive d'un empire médiéval XXIe-XIVe siècle by Hadrien Collet pg 236-237, 240)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 11

African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa By Michael Gomez pg 106, Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 11, n.3

Travels of Ibn Battuta Vol4 pg 951-952, 956, 967, 970-971

This is a very rich historiographical commentary but a couple of thoughts that are worth taking on board:

1) I think you need to dig into Gomez' entire argument about interpreting these sources more carefully, and to take note that he published considerably after Hunwick, who died in 2015. E.g. Hunwick's analysis is not a reply to Gomez, but Gomez' arguments about how to read these sources is in many ways an argument against Hunwick's interpretations. To some extent Hunwick's response to this specific issue (the number of people in Mansa Musa's entourage and the type of people in it) rested on a sort of common-sense empiricism, which is often how modern historians react to estimates of numbers in medieval and classical sources. Gomez is very invested in seeing the Tarikh in particular but other Islamic sources as scholarly and careful rather than fabulistic or exaggerated, and in arguing that Islamic scholars of that era had a distinctive methodological commitment to a kind of historical accuracy that derived from training in how to read hadith and evaluate their legitimacy. Which among other things did create a fairly specific attention to whether something was hearsay or not, as you note in this essay.

2) Following on this point, I do think there's an interesting general debate about how to read numbers in medieval and classical sources from all over the Mediterranean, West Africa and Near Eastern world. Historians are often confronted with numerical claims that seem improbable or exaggerated, and when we trace out where those claims come from, we often find that various chroniclers are just repeating something that another chronicler said with none of them being direct eyewitnesses to the event whose numerical size is being estimated. In general, as a non-specialist in medieval and classical history, I'd say that the importance we put on direct eyewitnessing in terms of accuracy is something that almost no medieval or classical source from that vast range of regions was invested in. Even travellers' accounts like Battuta's sometimes mix in reports from other travellers *as if the author experienced that directly* and it takes careful attention to note that. (You even see this in European exploration from the 15th-19th C.,) We tend to think this makes the source less reliable, but I think we have to be careful about that assumption. When you're reading Herodotus, for example, you can't just generically regard his reports as unreliable because he was simply reproducing what he was told by other people--the complexity is that some of those reports seem closer to reality than others, as we might expect if we sat down in the company of a set of well-travelled people today and asked them to tell us about what they'd seen.

My feeling is that numbers are the same thing--sometimes they're fabulistic or get distorted by the way various medieval chroniclers (Islamic or otherwise) reproduced what they'd heard or seen in other writings, and sometimes not so much. In this case, when you look at the rich variety of sources you're discussing here, you see the Tatimmat al-muḫtaṣar as creating a specific large number when the sources written earlier declined to do so, which you take to then be the source of later exaggerations and amplifications. The problem is that the slightly earlier accounts indicate amounts that aren't necessarily in sharp contradiction to "10,000": "thousands of his soldiers" and "a large crowd" and moreover, if you look carefully, the "thousands of his soldiers" is what Mansa Musa "presents for the pilgrimmage"--it may well be precisely not the entirety of the party travelling with him from Mali. (Which might have included some people who were not Muslims who supported the pilgrimmage but were not participants; most especially perhaps people who had servile status of some kind--the duality of Mali's population and of the way its rulers had to signify power in both Muslim and non-Muslim idioms in this era is a major theme in Gomez and other recent historical scholarship.)

Some of it comes down to whether observers and then later chroniclers would have been particularly observant about or attentive to fine-grained distinctions between the types of people in Mansa Musa's entourage; or would bother to comment on the specific composition of it. It's possible to imagine his group arriving, for example, and instantly losing some portion of its size because some of them were Tuaregs who were managing the caravan but were not Mansa Musa's direct subjects, and with them might have gone some portion of people in the entourage who were not slaves or servants of Mansa Musa but who were brought by the caravan to be sold in Cairo or between Cairo and Mecca. E.g., what Mansa Musa's entourage was in terms of its composition is itself a complicated question that in turn has a lot of implications for how big it might have been, and whether even the eyewitness chroniclers were viewing all of what we might consider to have been the full group is an open question.

Thank you for this, this is new wow!