What did they write about? : An intellectual history of Timbuktu ca. 1450-1900.

No single body of primary sources in the literary heritage of West Africa has attracted as much attention and attained as much celebrity as the fabled manuscripts of Timbuktu.

An estimated 350,000 manuscripts1 have been inventoried from the dozens of old libraries of the city of Timbuktu, whose reputation for education and its medieval monuments have been favourably compared to universities. This trove of literary treasures is testimony to the great intellectual achievements of the scholars of the city, which distinguished itself as a center of study, attracting students from West Africa, the Maghreb, and beyond.

This article explores the intellectual history of Timbuktu since the late Middle Ages, and provides an overview of the writings of its scholars, focusing on the original works composed by local intellectuals.

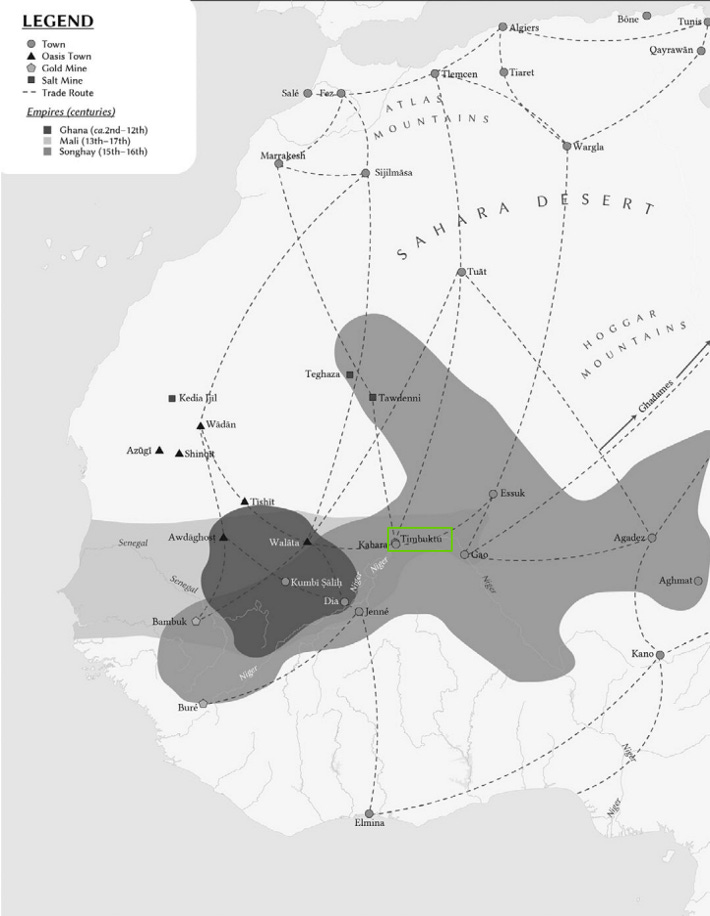

Map showing the city of Timbuktu and the largest empires of medieval West Africa.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

A brief background on the history of Timbuktu

‘Timbuktu had no equal among the cities of the Sūdān ...and was known for its solid institutions, political liberties, purity of morals, security of its people and their goods, compassion towards the poor and strangers, as well as courtesy and generosity towards students and scholars.’

Tarikh al-fattash, 1665.2

Like most of the old cities of West Africa, the urban settlement at Timbuktu emerged much earlier than its first appearance in textual accounts as a seasonal camp for nomadic groups in the 11th century. There’s evidence for Neolithic settlements near and around the old town dating back to the mid-1st millennium BC, with intermittent settlements continuing through the 1st millennium CE. 3

Timbuktu remained a minor town for much of its early history before the 14th century, when it was conquered by the Mali empire. After his famous pilgrimage to Mecca, the Mali emperor Mansa Musa constructed Timbuktu’s first mosque in 1325 CE, known as the Jingereber/DjingareyBer. The city’s two other iconic mosques of Sankore and Sidi Yahya were constructed more than a century later during the brief rule of the Tuareg chief Akil (1433-1468) before the city was conquered by the Songhai empire.4

Timbuktu attained its celebrated status as the intellectual capital of West Africa during the Songhai period in the 16th century. This ‘golden age’ as recounted in the Timbuktu Chronicles was evidenced by the more than 150 Koranic schools with between 5,000-9,000 students and dozens of prominent scholarly families, all of whom owned extensive libraries.5

View of Timbuktu from the mosque of Sankore, ca. 1906, Edmond Fortier.

Several of the prominent families mentioned in the 17th-century chronicles were established during the Songhai period and remain prominent in Timbuktu today. Among the most prominent are the Baghayughus/Baghayoghos (a soninke family from Kabara and Jenne and are associated with the Sidi Yahya Mosque ), the Aqits (a Berber family from which Ahmad Baba and the chronicler Al’Sa’di was born and are associated with the mosque of sankore during the 16th century), the Gidados and Gurdus (fulani families associated with the Jingereber since the 16th century as well as the Sankore mosque during and after the 18th century).

[For more on these, please read my previous article on the social and political history of Timbuktu. ]

Medieval Timbuktu was part of a broader intellectual network of West African scholarly centers extending from the towns of Walata and Chinguetti in Mauritania to Jenne and Arawan in Mali. These scholarly networks extended across the Sahara to their peers in the Maghreb, such as the cities of Fez and Marrakesh in Morocco, as well as the cities of Egypt and the Hejaz, especially Cairo and Medina, which were visited by scholars from West Africa in the context of pilgrimage.6

Importantly, the establishment of Timbuktu’s intellectual tradition was strongly linked to the migration of scholars from the southern towns of Kābara and Diakha near the city of Djenne in the inland delta region of Mali, which made up the nucleus of the Wangara scholarly diaspora of medieval West Africa. In his biography of the Wangara scholar Modibbo Muhammad al-Kabari, who settled in Timbuktu in 1446, the 17th-century Timbuktu chronicler al-Saʿdi mentions that: “At that time the town was thronged by Sūdāni students, people of the west [ie, the inland delta region] who excelled in scholarship and righteousness. People even say that, interred with him in his mausoleum (rawda), there are thirty men of Kābara, all of whom were righteous scholars.”7

Street scene, Djenne, Mali. ca. 1906. Edmond Fortier.

Modibbo was a qadi of Timbuktu and an important scholar of the Sankore mosque, and his students included ‘Umar b. Muhammad Aqit, a Sanhaja scholar of the Massufa Berbers, whose Aqit family later provided most of the imams of the Sankore mosque during the 16th century. Another notable Wangara scholar was Muhammad Baghayogho (d. 1593), whose students included the famous Timbuktu scholar Ahmad Baba al-Tinbukti (d. 1627), who was the grandson of the aforementioned Umar Aqit, and was regarded as the most prolific and the most celebrated of Timbuktu scholars. Ahmad Baba considered Baghayogho the greatest scholar and renewer (mujaddid) of Timbuktu for the 16th century.8

The education system in Timbuktu during the classic period.

Timbuktu was thus integrated with the scholarly trends in West Africa and the wider Islamic world. Its scholars composed and copied various works and commentaries throughout the history of the city’s growth as a site of scholarship. Standard texts on law, theology, grammar, and what might be called the “Islamic humanities” were fully developed in Timbuktu. The “great books” of this vibrant intellectual tradition were studied extensively, and local scholars composed original works to teach students, who were required to have an intimate familiarity with these texts.9

The “core curriculum” of education in 16th/17th-century Timbuktu and the wider West African region was reconstructed by the historians Bruce Hall and Charles Stewart, based on their analysis of 21,000 extant manuscripts from 80 West African manuscript libraries. This core curriculum comprised “texts available to advanced scholars and described in their own writings” as well as “the core didactic texts studied by all aspiring students.” A more recent study of 31 library inventories in Timbuktu alone by Charles Stewart showed that at least three-quarters of known authors in the inventories also appear in the “Core Curriculum,” thus corroborating the earlier research.10

Their evidence led them to divide the curriculum into a few major subjects: Quranic studies, Arabic language, Belief/theology (tawhid), mysticism (tassawuf), Hadith, Literature/Poetry, Jurisprudence and law, Ethics, Sciences, and History, among other subjects. This West African curriculum closely resembles the ideal type developed across the Islamic world during the classical period from Fez to Cairo.11

Elementary education in Timbuktu, as in all its peers, began with writing, grammar, and memorizing the Quran and some devotional poetry. Some of the students would proceed through to the higher levels, which entailed the learning of Arabic grammar —the language in which most texts were written; memorization of classical poetry because of their literary quality; studies on the life of the Prophet, and studies on theology.12

The biographies of Timbuktu scholars such as Ahmad Baba (d. 1627) and al-Saʿdī’ (d. 1656) regarding their eductation indicate that other disciplines were available for advanced study in 16/17th-century Timbuktu including rhetoric, logic, astronomy, as well as works on mathematics (calculus, geometry), geography, philosophy, botany, medicine (pharmacopeia, medicinal plants), astronomy, astrology, mysticism, dogma, esoteric sciences, geomancy and music.13

Teachers issued individual licences or ijaza authorizing students in turn to teach particular texts. Only those who mastered all the texts would be recognized as genuinely learned; those who started the course of reading but did not finish might have become good teachers in the elementary classes but could not be called learned (‘alim or faqih).14

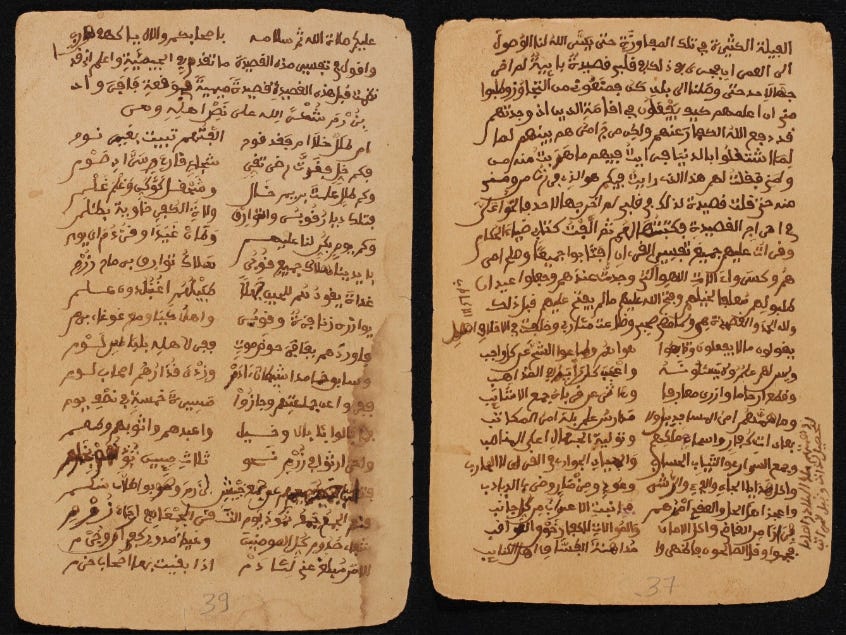

Ijāzah from Abū Bakr Fofana to al-Ḥājj Sālim Suwaré. 18th-20th century. Aboubacar Ben Said Library. images from HMML Reading Room with the permission of SAVAMA-DCI, Num. SAV ABS 04246.

‘An ijāzah of Qur'anic study that runs through the Saganogo family.’ al-Ḥājj Sālim Suwaré was a central figure in the scholarly traditions of the Wangara. Fofana and Saganogo are both soninke patronymics of northern Mande-speaking groups.

The mosques of Djingereber, Sankore, and Sidi Yahia could used as locations for classes, but much of the day-to-day teaching process took place in scholars’ houses in special rooms set apart, where the scholar had his own private library which he could consult when knotty points arose. The semi-itinerant social organization in parts of the broader region influenced the way learning and teaching took place. The tutor would be compensated by the student with money, goods, or services depending on their means.15

The teaching tradition of 16th-century Timbuktu is best summarised in the biography of the scholar Muhammad Baghayogho that was written by his pupil Ahmad Baba. It begins with a description of the character of his teacher and the length of time he studied under him, the various works he was taught, and the conclusion of Ahmad Baba’s studies when he acquired a certificate from Baghayogho to teach.

“Muḥammad b. Maḥmūd b. Abi Bakr al-Wangari al-Tinbukti, known as Baghayogho…Our shaykh and our [source of] blessing, the jurist, and accomplished scholar… he was constantly attending to people's needs, even at cost to himself … his lending of his most rare and precious books in all fields without asking for them back again, no matter what discipline they were in…Sometimes a student would come to his door asking for a book, and he would give it to him without even knowing who the student was. In this matter he was truly astonishing, doing this for the sake of God Most High, despite his love for books and [his zeal in] acquiring them, whether by purchase or copying.

Besides all this, he devoted himself to teaching until finally he became the unparalleled shaykh of his age in the various branches of learning. I remained attached to him for more than ten years, and completed with him the Mukhtaṣar of Khalil… the Muwatta … the Tas’hil of Ibn Malik… the Uṣūl of al-Subki with al-Maḥallī's commentary… the Alfiyya of al-Iraqi.. the Talkhiṣ al-miftāḥ with the abridged [commentary] of al-Sa ̊d… the Sughrā of al-Sanūsī and the latter's commentary on the Jaza'iriyya, and the Ḥikam of Ibn Aṭā Allāh with the commentary of Zarruq, the poem of Abu Muqrio, and the Hāshimiyya on astronomy together with its commentary, and the Muqaddima of al-Tājūrī on the same subject, the Rajaz of al-Maghīlī on Logic, the Khazrajiyya on Prosody, with the commentary of al-Sharif al-Sabti, much of the Tuhfat al-ḥukkām of Ibn Aṣim and the commentary on it by his son… the Fari of Ibn al-Ḥājib.. the Tawḍīḥ.. the Muntaqă of al-Bājī.. the Mudawwana with the commentary of Abū 'l-Ḥasan al-Zarwīlī, and the Shifa of Iyāḍ… the Ṣaḥīḥ of al-Bukhārī.. the Ṣaḥiḥ of Muslim.. the Madkhal of Ibn al-Ḥājj, and lessons from the Risāla and the Alfiyya and other works. I undertook exegesis of the Mighty Qur'ān with him to part way through Surat al-A'raf … the entire Jāmi al-mi’yār of al-Wansharīsī.

In sum, he is my shaykh and teacher; from no one else did I derive so much benefit as I did from him and from his books. He gave me a licence in his own hand for everything for which he had a licence and for those works for which he gave his own.”16

The intellectual production of Timbuktu.

From the extant texts in the libraries of the region, it is clear that the body of scholarly works studied and taught in Timbuktu followed established patterns of higher education in the more famous centers of the Maghreb and the Middle East. These works included those written by local scholars, which reflects a deep engagement and confidence in their own scholarship.17

By the 15th century, Timbuktu’s scholars were producing original works as well as compiling new derivations and commentaries on established texts.

Original writings by Timbuktu scholars include the historical chronicles (tarikh), correspondence, poems, theological writings, legal opinions (fatwas), works on medicine, astronomy, astrology, commerce, as well as commentaries and annotations of works by both local and external scholars. There were also ajami manuscripts, which were written in local languages such as Songhay, Bambara, Fulfulde, and Tamasheq.18

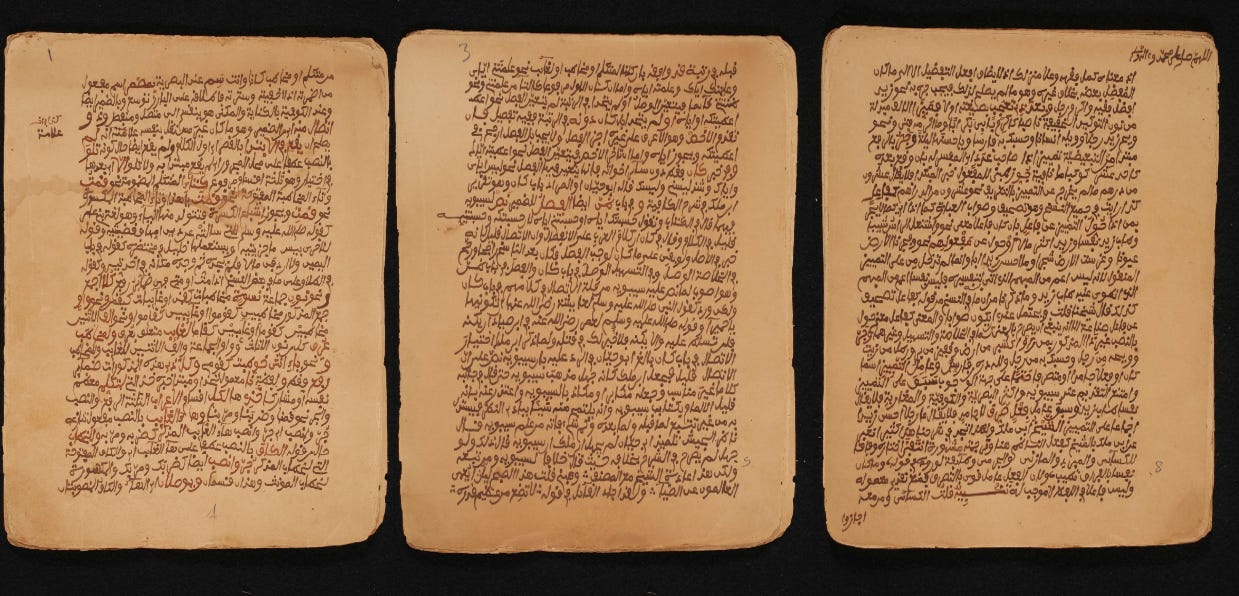

The Tarikh genre of chronicles is arguably the best-known collection of original works of history produced in Timbuktu. These chronicles are: the Tarikh al-Sudan (Chronicle of the Sudan) of al-Sa’di (ca. 1656); the Tarikh al-Mukhtar (ca. 1664), previously known as the Tarikh al-Fattash; and the Notice historique (ca. 1669), all of which were written by scholars whose families came from Timbuktu.

The Tarikhs, which were partly inspired by chronicles on early Islamic history that circulated in the region, also influenced later writings of local history in and around Timbuktu, such as the 18th century chronicles of the Timbuktu Pashalik like the Tadhkirat al-Sudan (ca. 1751), Mawlay Sulayman’s Diwan al-Sudan, and the Dhikr al-izam (ca. 1801), and various smaller chronicles from the 19th and early 20th century about scholarly families and genealogy, as well as copies of chronicles about neighbouring empires like Massina and Sokoto.19

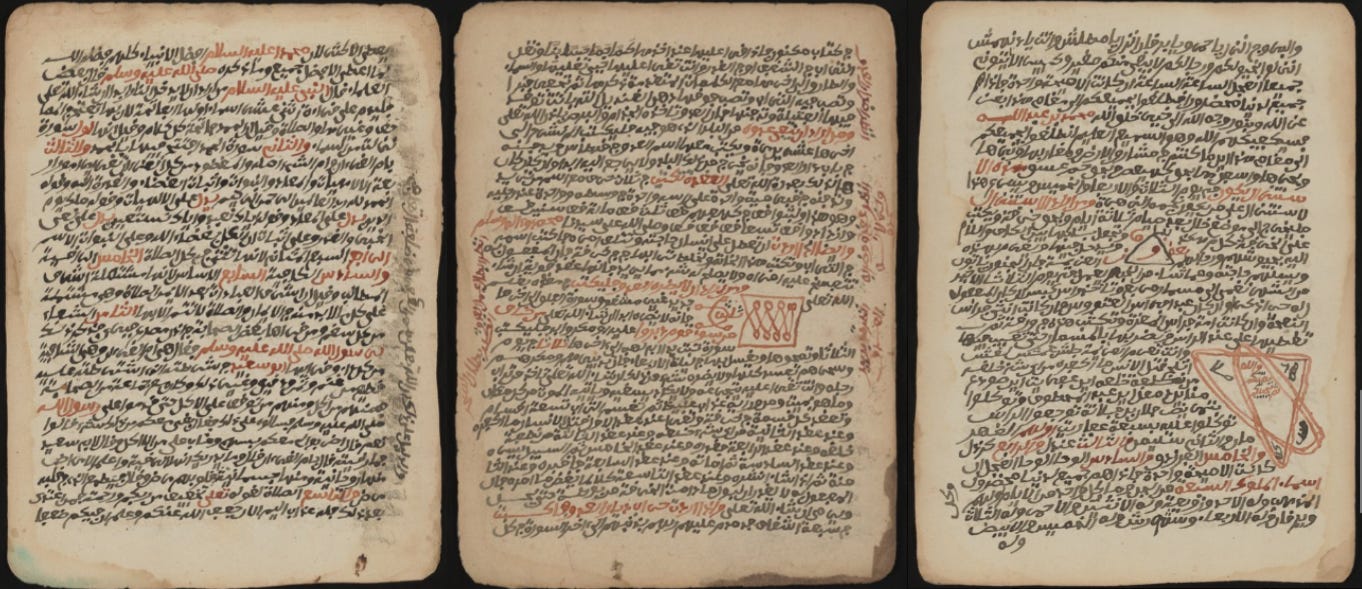

copy of the Tārīkh al-Sūdān of al-Sa’di. 18th-20th century, Mamma Haidara Library. images from HMML Reading Room with the permission of SAVAMA-DCI, Num. SAV BMH 34122.

Taḏkirat al-Sūdān, 19th century, BNF, Paris.

Account of an earthquake by Aḥmad ibn Bindād Māsinī, ca. 1755. Bibliothèque de Manuscrits al-Imam Essayouti. images from HMML Reading Room with the permission of SAVAMA-DCI, Num. ELIT ESS 03799.

‘the main text concerns an event the author dates to Sunday 29 (27) Muḥarram 1169 AH or October 22 in the Julian calendar, corresponding to the Lisbon earthquake of 1 November 1755 CE.’ the name ‘Māsinī’ was commonly used by scholars from the Masina region of Mali.

Historical note on Ahmad Lobbo and the founding of Hamdallahi (ie, the Massina empire), 19th-20th century, Bibliothèque de Manuscrits al-Imam Essayouti. images from HMML Reading Room with the permission of SAVAMA-DCI, Num. ELIT ESS 02177.

Tazyīn al-waraqāt by Abdullahi dan Fodio (d. 1829). Mamma Haidara Library. images from HMML Reading Room with the permission of SAVAMA-DCI, Num. SAV BMH 27112.

An account of the Sokoto wars of 1804. Sokoto was an empire in northern Nigeria whose rulers were in close contact with the Massina empire that claimed suzerainty over Timbuktu during the 19th century.

Military expeditions of the Prophet and the first caliphs. 18th-20th century, Mamma Haidara Library. images from HMML Reading Room with the permission of SAVAMA-DCI, Num. SAV BMH 13387.

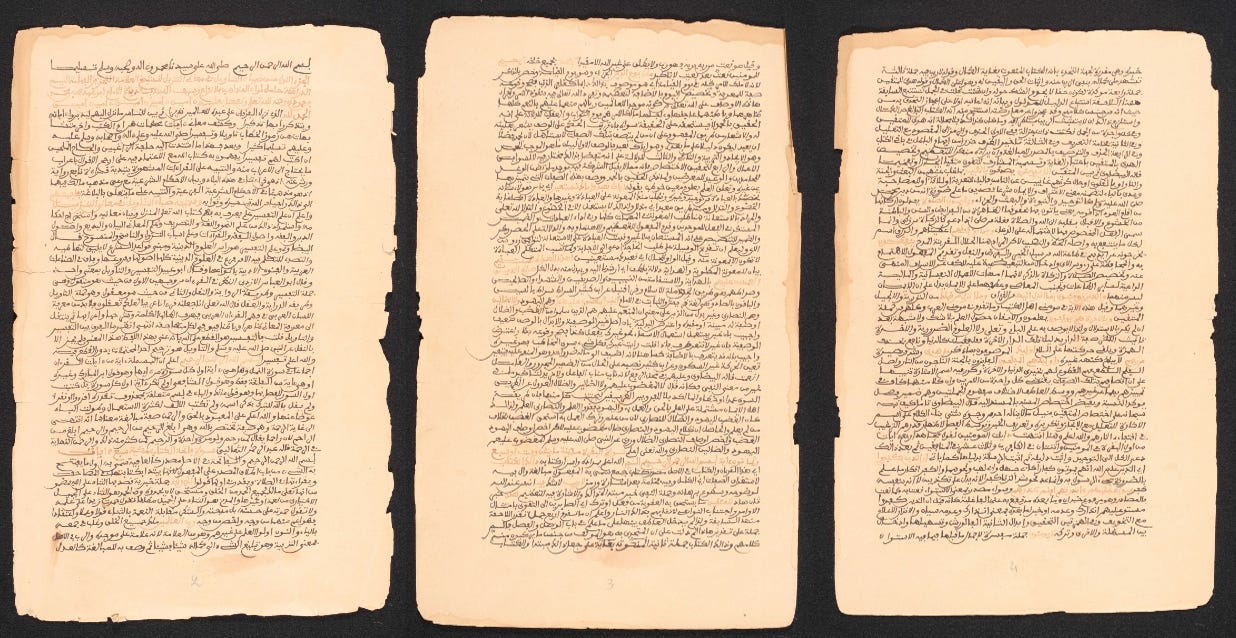

Local scholars also wrote treatises, legal texts and opinions (fatwa) relating to issues such as politics and legitimacy of rulers, trade and inheritance, marriages and divorce, manumission and enslavement, etc. An example of these is the famous anti-slavery treatise by Ahmad Baba al-Tinbukti (d. 1627) titled Mi‘raj al-Su‘ud, which is a critique of the enslavement of free-born Muslims from West Africa, and the Tanbīh al-wāqif, which was an explanation of the Mukhtasar of Khalil, an important work on Maliki law.20

Mi'rāj al-Ṣu'ūd ilá nayl Majlūb al-Sūdān (The ladder of ascent in obtaining the procurements of the Sudan: Ahmad Baba answers a Moroccan's questions about slavery) ca. 1615, Mamma Haidara Library.

Tanbīh al-wāqif ʻalá taḥqīq Wa-khaṣṣaṣat niyyat al-ḥālif by Ahmad Baba, 18th-20th century. Bibliothèque de Manuscrits al-Imam Essayouti. images from HMML Reading Room with the permission of SAVAMA-DCI, Num. ELIT ESS 00104.

West African scholars, including some from Timbuktu and its neighbouring town of Arawan, appear frequently in works regarding medicine, esoteric sciences, and Sufism (tasawwuf ), which were part of the texts studied by students in the region.

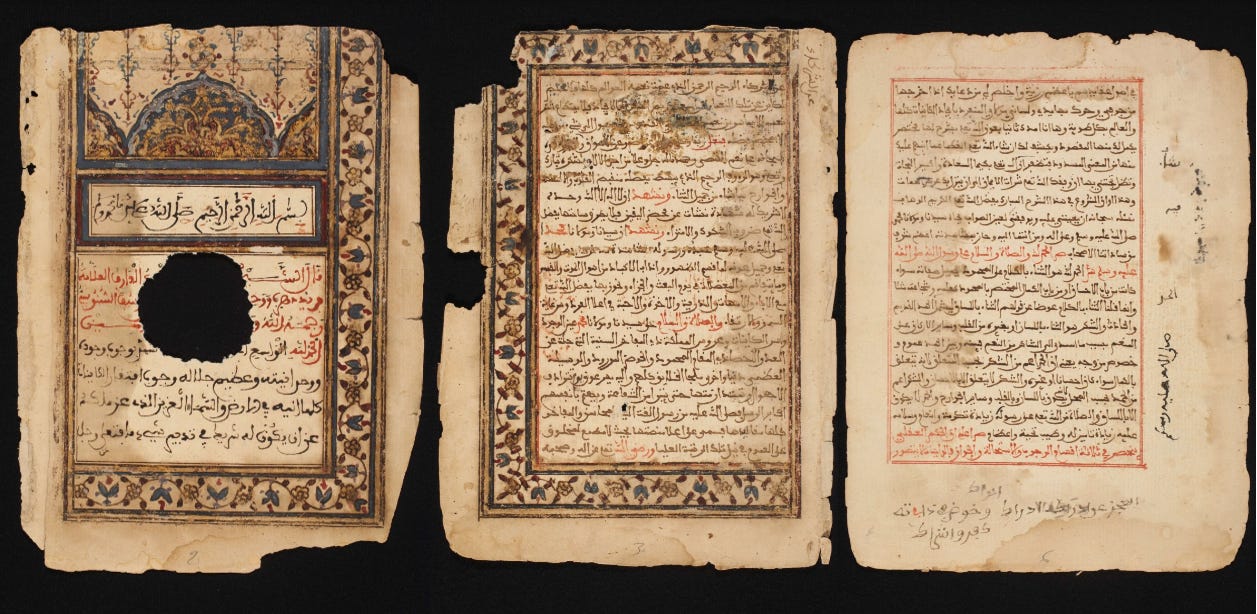

What is arguably the earliest extant manuscript from Timbuktu is a treatise on theology and esoteric sciences by Muhammad al-Kābarī (c. 1450) titled Bustān al-fawā’id wa-l-manāfiʿ (“The Garden of Excellences and Benefits”). Al-Kabari, who was among the celebrated sudani (ie, ‘black’) Soninke scholars from Kabara mentioned in the introduction, was one of the most significant scholars of the period, having taught several prominent families of the Mali and Songhai era.21

A more scientific work on medicine was written by Ahmad al-Raqqadi al-Kunti (d. 1684), an important scholar who directed a Zawiya (sufi lodge) in Arawan, just north of Timbuktu. Al-Kunti authored a 600-page medical treatise titled ‘Kitāb Shifāʾ al-asqām’ (The Book on curing the external and internal illnesses to which the body is exposed.) It is an encyclopedic compendium of medicine that offers a general audience a holistic approach to physical, mental, and spiritual afflictions. It combines Galenic humoral medicine, prophetic medicine, and traditional medicine, citing Hippocrates and Galen, as well as the Arab physician Al-Harith ibn Kalada (d. 634), Ibn Sina, among others.22

'Garden of Excellences and Benefits in the Science of Medicine and Secrets' by Modibbo Muhammad al-Kābarī ca. 1450, Timbuktu. Northwestern University.

copy of the Shifāʼ al-asqām al-ʻāriḍah fī al-ẓāhir wa al-bāṭin min al-ajsām by Ahmad al-Raqqadi al-Kunti, 18th-20th century, Mamma Haidara Library. images from HMML Reading Room with the permission of SAVAMA-DCI, Num. SAV BMH 00116.

Writings on Sufism (tasawwuf ) include various writings from scholars of the Kunta family, such as Aḥmad al-Bakkāy al-Kuntī’s (d. 1865) Qasida fi tawassul, as well as those written by Sıdi Muhammad al-Kuntı and Sıdi al-Mukhtār al-Kuntı. Other West Africans whose works on esoteric sciences and devotional texts were found in the Timbuktu manuscript collections include Muhammad al-Wālı's Manhal al-raab and Bad al-Fulāni's Manzuma fı al-mawā'iz: and Qasıda Banat su’ād, which were also used in the context of education as part of the curriculum of Timbuktu’s schools.23

An example of a work on Sufi mysticism from the Timbuktu manuscript collections was one written by an 18th-century scholar named Yusuf Ibn Said al Filani, whose nisba indicates an origin from the Fulbe groups of West Africa. The work is titled: ‘Adurar al munazamah fi tadmim addunya al muqabaha’ ( ‘The prosody of pearls that limit the deleterious effects of the abhorrent world’). The various footnotes, margin notes, and notations found in the manuscript indicate that it was used as an educational reference for topical discussions within educational settings.24

The Prosody of Pearls that Limit the Deleterious Effects of the Abhorrent World by Yusuf ibn Sa'id Fulani, 18th century, Mamma Haidara Library.

The Timbuktu manuscript collections also contain some original works on theology written by West African scholars such as the Mauritanian scholar al-Yadali (d. 1753), and the Sokoto scholar Abdullahi dan Fodio (d. 1829), whose writings on Exegesis (tafsīr) were studied alongside those of al-Baghdadi (d. 1340), and al Suyuti (d. 1505). Another commonly cited local scholar was Umar b. Abi Bakr al-Kanawi, whose work on correspondence and letter-writing appears across many Timbuktu libraries.25

Ḍiyāʾ al-taʾwīl fī maʿānīʾl-tanzīl, a work on Tafsīr by Abdallahi dan Fodio. 19th century, Bibliothèque al-Cady al-Aqib. images from HMML Reading Room with the permission of SAVAMA-DCI, Num. ELIT AQB 01511.

Dālīyat al-Sughrá, ca. 1786. Mamma Haidara Library. images from HMML Reading Room with the permission of SAVAMA-DCI, Num. SAV BMH 20787.

‘Poem in praise of the Prophet. Preceded by a citation from Tabṣirat al-Fattāsh, a history of the scholars of Djenne, page 1. This is likely to be the chronicle entitled Tārīkh al-Fattāsh or Tārīkh ibn al-Mukhtār.’

Other works found in the collections include writings on astronomy, arithmetic, trade, agriculture and handicrafts, travel writing (rihla), and a large corpus of ajami manuscripts written in local languages as well as Arabic manuscripts with glosses in ajami. The ajami manuscripts extend to all fields of scholarship, and include traditional medicine, plants and their properties, esoteric sciences, and diplomatic correspondence.

One of the astronomical manuscripts of Timbuktu that has been studied was the work of was a commentary written by the Timbuktu scholar Abul Abbas al-Ghalawi, about the work of Mohammed bin Ya-aza. The treatise, which was used as a teaching manual for students in 1723, explains the purposes of studying astronomy: guiding people on and off the sea, determining calendars, and determining prayer times. A similar manuscript from Timbuktu that was written around the same time by an anonymous author shows the diagrams of planetary orbits. 26

(left, first two images) Kashf al-Ghummah fi Nafa al-Ummah (The Important Stars Among the Multitude of the Heavens) by Abu al-Abbas al-Tawathi al-Ghalawi, ca. 1733. Mamma Haidara Library. (right) manuscript showing the rotation of the planets. images by Rodney Thebe Medupe et al. The nisba of al-Ghalawi appears in the names of few West African scholars, eg Abu Bakr al-Ghalawi, a student of the 18th century Timbuktu scholar Muhammad al-Zaidi, who was taught by the 17th century scholar Muhammad Baghayogho, the son of Ahmad Baba’s teacher of the same name.27 A later work from the 19th century Kunta scholar Sidi al-Bakkai titled ‘Risalat al-Ghalawiyat’, which was written as an address to ‘the turbulent and practically pagan Ghalawi tribe’, indicates that the Ghalawi were a section of the Tuareg.28

[ related essay: Star-gazing from the cliffs of Bandiagara; truths and mysteries of Dogon astronomy in the west African context.]

Work on astronomy by Ibn Saeed el-Kibari, 14th-19th century, Mamma Haidara Library. His nisba is more accurately written as ‘al-Kābari’, and it was associated with Wangara scholars from Kabara near Djenne, who made up the earliest group of scholars in Timbuktu, such as the aforementioned 15th-century scholar Muhammad al-Kabari.

The travels of al-Ḥājj ʻUmar Tal. 19th century. Aboubacar Ben Said Library. images from HMML Reading Room with the permission of SAVAMA-DCI, Num. SAV ABS 01761.

The text details the life of ʻUmar Tal, founder of the Tukulor empire, including his passage through Masina and Sokoto on his pilgrimage to Mecca.

Sullam al-Aṭfāl fī Buyū' al-Ājāl (The beginner's guide to commercial transactions) by Aḥmad ibn Bawḍ ibn Muḥammad al-Fulānī. 19th century. Mamma Haidara Library. ‘This volume delineates the obligations of parties to commercial exchanges and contracts, concentrating on sales and how individuals loaning money are to be protected in commercial transactions.’

Book of the Blessed Merits of Crafts and Agriculture. 15th-19th century, Mamma Haidara Library. ‘The social benefits of trades, crafts, and agricultural pursuits are discussed in this book. The anonymous author describes the contributions to society of various vocations and expresses the fundamental dignity that individuals acquire by working in socially useful jobs.’

Kasb al-faqīr by Umar Tal, 19th century. Mamma Haidara Library. images from HMML Reading Room with the permission of SAVAMA-DCI, Num. SAV BMH 30037.

Includes gloss in Arabic and Bambara ʻajamī.

Book copying in Timbuktu.

A veritable copying industry flourished in Timbuktu by the 16th century, with copyists, proofreaders, and editors well known for their skills.

The copying industry in Timbuktu appears to have been extensive and well organized. The quality of the paper material used in Timbuktu and the nature of storage meant that all manuscripts, whether originally composed locally or imported from beyond Timbuktu, required re-copying at 150–200 year intervals if they were to remain extant.29

The vibrant copying industry of the city is evidenced by the colophons at the end of the manuscripts, which cite not only the title and author, but also the date of the manuscript copy and the names of the scribes who produced it. They at times included the names of the proofreader and the fees paid to the copyists.30

Two volumes of the Muhkam by Ibn Sidah, which were commissioned by the scholar Anmad b. Anda ag Muhammad, contains remarkable evidence of the copying industry in late-16th-century Timbuktu. They each feature a second colophon, in which the proofreader records that he verified the accuracy of the copying and records what he was paid. The copyist received 1 mithqal of gold per volume, and the proofreader half that amount. Manuscript copying was a professionalized business, and compensation was paid by legal contract, with the copyist and proofreader working full time to complete their contracted tasks.31

The most important works copied locally include: lexicons (dictionaries of the Arabic language), such as those written by Fayruzabadi (d. 1415) and Ibn Sida (d. 1066), prayer books such as the of Dalāʼil al-khayrāt by Muhammad al-Jazuli (d. 1465), works on sunni theology such as those by al-Sanūsī (d. 1489), and various copies of works on Maliki law, such as the Mukhtaṣar of Khalīl among others.32

Related to these were commentaries by local scholars on grammar, theology, and law, such as a commentary on al-Ṣuyūṭī's grammar by the scholar Muḥammad Bābā (d. 1606) titled: al-Minaḥ, and a versification of al-Sanusi’s work on tawḥīd (belief) by the scholar Muhammad b. Abi Bakr Baghayogho al-Tınbuktı (d. 1655) titled Nazm saghırı.33

copy of the dictionary of Fayruzabadi (d. 1415), 18th century, Aboubacar Ben Said Library. images from HMML Reading Room with the permission of SAVAMA-DCI, Num. SAV ABS 03132.

A commentary of Umm al-Barāhīn of Muḥammad Ibn Yūsuf al-Sanūsī, 18th-20th century, Mamma Haidara Library. images from HMML Reading Room with the permission of SAVAMA-DCI, Num. SAV BMH 35986.

This is a work on Sunni dogmatics.

al-Minaḥ al-ḥamīdah fī sharḥ al-Farīdah by Muḥammad Bābā Tinbuktī (d. 1606), 18th-20th century. Bibliothèque de Manuscrits al-Imam Essayouti. images from HMML Reading Room with the permission of SAVAMA-DCI, Num. ELIT ESS 00305.

This is a commentary on the Alfiyya of al-Suyuti. Hunwick lists Muhammad Baba among the Baghayogho scholarly family of Timbuktu.34

Tafsīr al-Jalālayn, 18th century. Bibliothèque de Manuscrits al-Imam Essayouti. images from HMML Reading Room with the permission of SAVAMA-DCI, Num. ELIT ESS 04951.

This work on Sunni belief that was written by al-Suyuti was copied by an anonymous West African scholar who added ajami glosses and a 2-page decoration. It’s written in the Suqi script of Timbuktu that was introduced by the Kel Es-Suq.35

The prayerbook Dalāʼil al-khayrāt, copied by Abu Bakr ibn Sayyid, 18th-20th century, Aboubacar Ben Said Library. images from HMML Reading Room with the permission of SAVAMA-DCI, Num. SAV ABS 03145.

The prayerbook Dalāʼil al-khayrāt, copied by Abdul Rahman bin Imam Zaghiti, 13th November, 1855 CE. Bibliothèque al-Cady al-Aqib. images from HMML Reading Room with the permission of SAVAMA-DCI, Num. ELIT AQB 00013.

The Zaghiti/Zaghaiti nisba is associated with the Wangara diaspora of West African scholars; one such family is attested at Kano in the 15th century and Timbuktu and Gao during the 16th/17th century.36

Conclusion: Demystifying Timbuktu

‘For too long, Timbuktu has been a place everyone has heard of but cannot find on the map; a place which has been described as more a myth or a word than a living city. Through conservation, cataloguing, and study of its manuscripts, Timbuktu is now being revealed as a city with a rich written history. In the process, our notion of Timbuktu is shifting from it being the ‘end of the world’ to an important historic centre of Islamic scholarship and culture.’

J. Hunwick

View of Timbuktu, with Mansa Musa's Djinguereber madrassa in the background. ca. 1895, Mali. Archives nationales d'outre-mer

My latest Patreon article explores the history of the African diaspora in Cyprus from the Bronze Age to the late medieval period.

Please subscribe to read about it here:

This figure is taken from a consortium of private libraries called the Sauvegarde et Valoris ation des Manuscrits pour la Défense de la Culture Islamique, (SAVAMA-DCI) which is involved in the digitization of all the manuscripts in collaboration with The Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures, University of Hamburg (CSMC), and the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library (HMML), St. John’s University, Collegeville, Minnesota. SAVAMA-DCI, manuscripts do not include the national collection at IHERIAB, and two other important private libraries, the Fondo Kati and the Imam Assuyuti Library. Stewarts provides a total estimate of 348,531 manuscripts for the SAVAMA-DCI collections.

see: What’s In the Manuscripts of Timbuktu? A Survey of the Contents of 31 Private Libraries by Charles C. Stewart pg 4-6

The Hidden Treasures of Timbuktu: Rediscovering Africa's Literary Culture by John Owen Hunwick, Alida Jay Boye pg 10

Prehistoric Timbuktu and its hinterland by Douglas Park

The great mosque of Timbuktu by Bertrand Poissonnier, Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick and ʻAbd al-Raḥmān ibn ʻAbd Allāh Saʻdī, pg 32, 69, 88, 94

African Dominion by Michael A. Gomez pg 280-285, Social History of Timbuktu: The Role of Muslim Scholars and Notables 1400-1900 by Elias N. Saad pg 89-90,

The Hidden Treasures of Timbuktu: Rediscovering Africa's Literary Culture by John Owen Hunwick, Alida Jay Boye pg 86-87

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Saʿdi's Taʾrīkh Al-Sūdān Down to 1613, and Other Contemporary Documents by John O. Hunwick pg 69, xxviii-xxix, lvii-lviii

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Saʿdi's Taʾrīkh Al-Sūdān Down to 1613, and Other Contemporary Documents by John O. Hunwick pg lvii-lviii, 62-68, Arabic Literature of Africa, Volume 4: The Writings of Western Sudanic Africa edited by John O. Hunwick, R. Rex S. O'Fahey pg 31

Timbuktu Scholarship: But What Did They Read? by Shamil Jeppie pg 216

The Trans-Saharan Book Trade: Manuscript Culture, Arabic Literacy and ... edited by Graziano Krätli, Ghislaine Lydon pg 113, What’s In the Manuscripts of Timbuktu? A Survey of the Contents of 31 Private Libraries by Charles C. Stewart pg 7-10)

What’s In the Manuscripts of Timbuktu? A Survey of the Contents of 31 Private Libraries by Charles C. Stewart pg 11, Timbuktu Scholarship: But What Did They Read? by Shamil Jeppie pg 218-219

But What Did They Read? by Shamil Jeppie pg 220-221

The Hidden Treasures of Timbuktu: Rediscovering Africa's Literary Culture by John Owen Hunwick, Alida Jay Boye pg 89-90

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Saʿdi's Taʾrīkh Al-Sūdān Down to 1613, and Other Contemporary Documents by John O. Hunwick pg lix, But What Did They Read? by Shamil Jeppie pg 218

West Africa, Islam, and the Arab World: Studies in Honor of Basil Davidson by John O. Hunwick pg 40-41, The Hidden Treasures of Timbuktu: Rediscovering Africa's Literary Culture by John Owen Hunwick, Alida Jay Boye pg 88

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Saʿdi's Taʾrīkh Al-Sūdān Down to 1613, and Other Contemporary Documents by John O. Hunwick pg 62-67

The Trans-Saharan Book Trade: Manuscript Culture, Arabic Literacy and Intellectual History in Muslim Africa by Graziano Krätli, Ghislaine Lydon pg 149

The Hidden Treasures of Timbuktu: Rediscovering Africa's Literary Culture by John Owen Hunwick, Alida Jay Boye pg 89, 94-97

The Meanings of Timbuktu by Shamil Jeppie, Souleymane Bachir Diagne pg 95-97

The Meanings of Timbuktu by Shamil Jeppie, Souleymane Bachir Diagne pg pg 184-189, Ahmad Baba on slavery by John Hunwick, Arabic Literature of Africa, Volume 4: The Writings of Western Sudanic Africa edited by John O. Hunwick, R. Rex S. O'Fahey pg 17-31

Invoking the invisible in the Sahara by Erin Pettigrew pg 55-57

Livre de la guérison des maladies internes et externes affectant le corps by Floréal Sanagustin, Kitāb Shifāʾ al-asqām, review by Cristina Álvarez Millán, An intriguing medical compendium by Justin Stearns

What’s In the Manuscripts of Timbuktu? A Survey of the Contents of 31 Private Libraries by Charles C. Stewart pg 25, The Meanings of Timbuktu by Shamil Jeppie, Souleymane Bachir Diagne pg 197-208, The Trans-Saharan Book Trade: Manuscript Culture, Arabic Literacy and Intellectual History in Muslim Africa by Graziano Krätli, Ghislaine Lydon pg 141-142

A Timbuktu Manuscript Expressing the Mystical Thoughts of Yusuf-ibn-Said by Maniraj Sukdaven et. al

The Trans-Saharan Book Trade: Manuscript Culture, Arabic Literacy and Intellectual History in Muslim Africa by Graziano Krätli, Ghislaine Lydon pg 119, But What Did They Read? by Shamil Jeppie pg 222, What’s In the Manuscripts of Timbuktu? A Survey of the Contents of 31 Private Libraries by Charles C. Stewart pg 13, 16)

African cultural astronomy by Jarita C. Holbrook et al pg 183-187.

Social History of Timbuktu: The Role of Muslim Scholars and Notables 1400-1900 By Elias N. Saad pg 249

The Caliphate of Hamdullahi Ca. 1818-1860 [i.e. Circa Eighteen Eighteen - Eighteen Sixty by William Allen Brown pg 224

The Trans-Saharan Book Trade: Manuscript Culture, Arabic Literacy and Intellectual History in Muslim Africa by Graziano Krätli, Ghislaine Lydon pg 149

The Hidden Treasures of Timbuktu: Rediscovering Africa's Literary Culture by John Owen Hunwick, Alida Jay Boye pg 93-94

West Africa, Islam, and the Arab World: Studies in Honor of Basil Davidson by John O. Hunwick pg 42

But What Did They Read? by Shamil Jeppie, pg 223-225, The Trans-Saharan Book Trade: Manuscript Culture, Arabic Literacy and Intellectual History in Muslim Africa by Graziano Krätli, Ghislaine Lydon, pg 120-139

What’s In the Manuscripts of Timbuktu? A Survey of the Contents of 31 Private Libraries by Charles C. Stewart, pg 12, n.22, 23, The Trans-Saharan Book Trade: Manuscript Culture, Arabic Literacy and Intellectual History in Muslim Africa by Graziano Krätli, Ghislaine Lydon, pg 137, Arabic Literature of Africa, Volume 4: The Writings of Western Sudanic Africa edited by John O. Hunwick, R. Rex S. O'Fahey pg 34

Arabic Literature of Africa, Volume 4: The Writings of Western Sudanic Africa edited by John O. Hunwick, R. Rex S. O'Fahey pg 34

Arabic Scripts in West African Manuscripts: A Tentative Classification from the de Gironcourt CollectionBy Mauro Nobili pg 125-131

Social History of Timbuktu: The Role of Muslim Scholars and Notables 1400-1900 By Elias N. Saad pg 58-59

Thank you for the wonderful information about the works held within the library. I've often wondered what specifically was contained in it, great information.

This is wonderful information, thank you. Were the manuscripts badly damaged when terrorists did a rampage in Mali some years ago?