A complete history of Mogadishu (ca. 1100-1892)

Journal of African cities: chapter 16.

Medieval Mogadishu was the northernmost city in the chain of urban settlements which extended about 2,000 miles along the East African coast from Somalia to Madagascar.

Centuries before it became the capital of modern Somalia, the old city of Mogadishu was a thriving entrepôt and a cosmopolitan emporium inhabited by a diversity of trade diasporas whose complex social history reflects its importance in the ancient links between Africa and the Indian Ocean world.

This article outlines the history of Mogadishu, exploring the main historical events and social groups that shaped its history.

Mogadishu in the Indian Ocean world, map by S. Pradines.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Mogadishu during the Middle Ages: (12th to 15th century)

The early history of Mogadishu is associated with the emergence of numerous urban settlements along the coast of East Africa extending from the city of Barawa about 200km south of Mogadishu, to the coast of Sofala in Mozambique and the Antalaotra coast of northern Madagascar. While much older entrepots emerged along the northern and central coast of Somalia in antiquity, the archaeological record of Mogadishu indicates that the settlement was established during the 12th century, not long before it first appeared in external sources.1

Mogadishu is briefly mentioned by a few authors in the 12th century, including Omar b. 'Ali b. Samura of Yemen, who mentions the arrival in Ibb of a scholar named “Ahmad ibn Al-Mazakban from the island of Maqdisu (Mogadishu) in the land of the Blacks.”2

The city was more extensively described by Yaqut (d. 1220) in the early 13th century, although the interpretation of his account is disputed since he didn’t visit it:

“Maqdishi is a city at the beginning of the country of the Zanj to the south of Yemen on the mainland of the Barbar in the midst of their country. These Barbar are not the Barbar who live in the Maghrib for these are blacks resembling the Zunij, a type intermediary between the Habash and the Zunij. It (Maqdishi) is a city on the seacoast. Its inhabitants are all foreigners (ghuraba’), not blacks. They have no king but their affairs are regulated by elders (mutagaddimin) according to their customs. When a merchant goes to them he must stay with one of them who will sponsor him in his dealings. From there is exported sandalwood, ebony, ambergris, and ivory—these forming the bulk of their merchandise—which they exchange for other kinds of imports.”3

The account of Al-Dimashqi in the second half of the 13th century also comes from an author who did not visit the city but was based on information collected from merchants. In his section on the “Zanj people,” he writes: “Their capital is Maqdashou [Mogadishu] where the merchants of different regions come together, and it belongs to the coast called of Zanzibar.” Al-Dimashqi also mentions “Muqdishū of the Zanj” in connection with trade via the Diba (Laccadive and Maldive) islands; it is the only place on the East African coast so mentioned. The ‘land of the Zanj’ in medieval Arab geographyy located south of the land of the Barbar, and most scholars regard it to be synonymous with the Swahili coast of East Africa.4

A more detailed account comes from Ibn Battuta who visited the city around 1331 and described it as “a large town.” Battuta notes that the “Sultan of Mogadishu is called Shaikh by his subjects. His name is Abu Bakr ibn Shaikh Omar, and by race he is a Barbar. He talks in the dialect of Maqdishī, but knows Arabic.” The historians Trimingham and Freeman-Grenville argue that the Barbar were Somali-speaking groups while Maqdishī was a proto-Swahili Bantu language, likely related to the Chimmini-Swahili dialect spoken in the southern city of Barawa.5

Combining these three main sources, historians argue that medieval Mogadishu was a cosmopolitan city inhabited not just by foreigners, but also by Somali-speaking and Swahili-speaking groups, similar to most of the coastal settlements that emerged along the coast, especially between the Juuba and Tana rivers. According to Lee Cassanelli, Randall Pouwels, and James de Vere Allen, the region between these two rivers was, during the Middle Ages, home to diverse communities of farmers, pastoralists, and traders with varied social and economic relationships. Their interactions resulted in the creation of complex societies with different political structures, including hierarchical systems of clientage with both autochthons and immigrants that linked the interior of southern Somalia with the Indian Ocean world.6

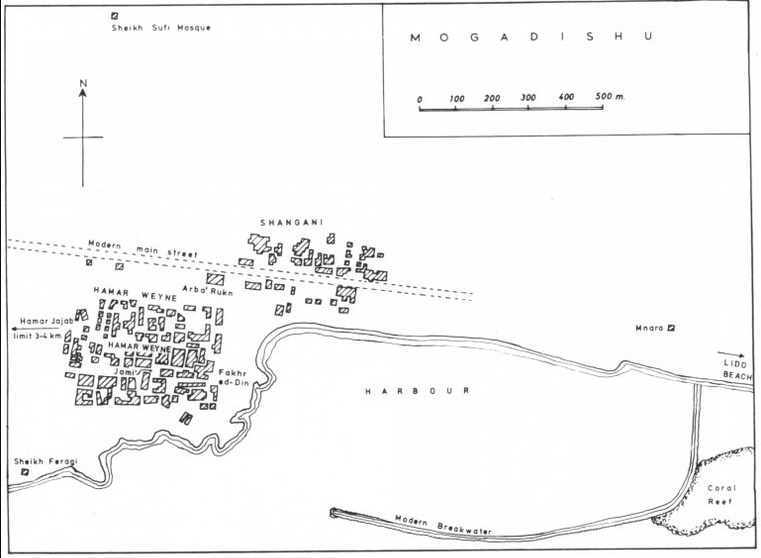

The above interpretation is corroborated by archaeological research on the early history of medieval Mogadishu. The old city consists of two distinct sections known locally as Shangani and Hamar-Weyne; the former of which is thought to be the older section. The excavations reveal that the extent of the medieval town was likely much larger than these two sections as indicated by the presence of the abandoned site known as Hama Jajab, as well as the location of the oldest mosques at the edges of both settlements.7

Mogadishu: surviving portions of the old town. Drawing by N. Chittick.

Excavations near the Shangani mosque revealed a long occupation sequence since the 11th/12th century and large quantities of local pottery were found including a mosque built in three phases beginning around 1200 CE. 8 The oldest levels (layers 7 to 8) contained pottery styles, labeled ‘category 5’ which are similar to those found in the 13th-century levels of the Swahili cities of Kilwa and Manda, while the later levels (layers 1-6) contained two distinct pottery styles; one of which was unique to the city, labeled ‘category 4’ and the other of which was similar to that found in other Swahili sites, labeled ‘category 6.’Excavations at both HamarWeyne and at Shangani also recovered small quantities of imported wares, with the earliest levels containing sgraffiato made in Aden and dated to the 13th century, while later levels contained Chinese porcelain.9

“Mogadiscio – Panorama del Quartiere di Amarnini” in the HamarWeyne section, early 20th century postcard.

The above archaeological record indicates that the early town of Mogadishu was mostly comprised of a predominantly local population with links to the cities of the rest of the East African coast, as well as southern Yemen.

Evidence for the presence of communities from the wider Indian Ocean world is indicated by the names provided on the inscriptions recovered from across the early town, mostly in Shangani. Of the 23 inscriptions dated between 1200 and 1365 CE, at least 13 can be read fully, and most of their nisbas (an adjective indicating the person's place of origin) indicate origins from Arabia in 10 of them, eg; al-Khazraji (from the Hejaz), al-Hadrami (from Hadramaut), and al-Madani (from Medina), with only 2 originating from the Persian Gulf. The most notable of the latter is the inscription in the mihrab of the mosque of Arba'a Rukun, commemorating its erection and naming Khusraw b. Muhammad al-Shirazi, ca. 1268-9 CE.10

The abovementioned inscription is the only epigraphic evidence of the Shirazi on the medieval East African coast,11 despite their prominence in the historical traditions of the region that has since been corroborated by Archaeogenetic research. The apparent rarity of these Persian inscriptions compared to the more numerous Arabic inscriptions, and the overwhelmingly local pottery recovered from Mogadishu and in virtually all Swahili cities undermines any literalist interpretations about the city's founding by immigrants.

[See my previous article on ‘Persian myths and realities on the Swahili coast’ ]

13th century Mogadishu was home to three main mosques, the oldest of which is the Jami' Friday mosque at Hamar Weyne, whose construction began in 1238 CE according to an inscription in its mihrab that also mentions Kalulah b. Muhammad b. 'Abd el-Aziz. Much of the present mosque only dates back to the 1930s when it was rebuilt and its size was significantly reduced, leaving the minaret cylindrical minaret and the inscription as the only original parts of the old mosque. Its construction was followed not long after by Muhammad al-Shiraz's mosque of Arba' Rukn in 1269, and the mosque of Fakhr al-Din in Hamar Weyne, also built in the same year by Hajji b. Muhamed b. 'Abdallah.12

The Mosque of Abdul Aziz and the Mnara tower in Mogadishu, ca. 1882.13 ‘The tower of Abdul-Aziz must be the minaret of an ancient mosque, on the ruins of which stands today another small mosque of more recent date and completely abandoned.’ 14

Jami Mosque of Kalulah in ḤamarWeyne, circa 1882. ‘the lighthouse towers of Barawa and Mogadishu are the most striking evidence of the civilization of these earlier centuries. From their situation and design there seems to be no doubt that these towers, which are about 12-25 metres high, did actually serve as navigational marks.’15

mosque of Fakhr al-Din, ca. 1822. Stéphane Pradines describes its plan and covering as rather atypical of East African mosque architecture including those in Mogadishu itself, linking it to Seljuk mosques.16

(left) Inscription at the entrance to the Fakhr al-Din mosque (right) entrance to a mosque in Mogadishu, Somalia, 1933, Library of Congress.

The three 13th-century mosques were associated with specific scholars, which corroborates the descriptions of Mogadishu as an important intellectual center in external accounts. The account of Ibn Battuta for example mentions the presence of ‘qadis, lawyers, Sharifs, holy men, shaikhs and Hajjis’ in the city. In his travels across western India, he visited the town of Hila where he encountered “a pious jurist from Maqdashaw [Mogadishu] called Sa‘īd,” who had studied at Mecca and Madina, and had traveled in India and China.17

During the early 14th century, Mogadishu transitioned from a republic ruled by an assembly of patricians to a sultanate/kingdom ruled by a sultan. This transition was already underway by the time Ibn Battuta visited the city, and found a ruler (called a ‘sheikh’ rather than a ‘sultan’), who was assisted by a constitutional council of wazirs, amirs, and court officials.18 In 1322, the rulers of Mogadishu began issuing copper-alloy coins starting with Abū Bakr ibn Muhammad, who didn’t use the title of sultan. He was then followed by a series of rulers whose inscriptions contain the title of sultan, with honorifics referring to waging war. A few foreign coins, including those from the 15th-century Swahili city of Kilwa, and Ming-dynasty China were also found.19

Mogadishu emerged as a major commercial power on the East African coast during the 13th and 14th centuries. Ibn Battuta's account mentions the city's vibrant cloth-making industry, he notes that “In this place are manufactured the woven fabrics called after it, which are unequalled and exported from it to Egypt and elsewhere.”20 Corroborating Al-Dimashqi earlier account, he also mentions links between Mogadishu and the Maldives archipelago: “After ten days I reached the Maldive islands and landed in Kannalus. Its governor, Abd al-’Aziz of Maqdashaw, treated me with honour.”21 An earlier account from the 13th century lists ‘Mogadishans’ among the inhabitants of the city of Aden (Yemen) alongside those from Ethiopia, East Africa, and the city of Zeila.22

The 16th-century Chronicle of the Swahili city of Kilwa in Tanzania also mentions that Mogadishu controlled the gold trade of the Sofala coast before it was supplanted by Kilwa during the early 14th century.23 The chronicle also refers to the arrival of groups from al-Ahsa who came to Mogadishu during its early history, and that Kilwa’s purported founder avoided the city because he was of African and Persian ancestry.24 The city is also mentioned in the Mashafa Milad, a work by the Ethiopian ruler Zara Ya’kob (r. 1434–1468), who refers to a battle fought against him at Gomut, or Gomit, Dawaro by the Muslims on December 25, 1445.25

Accounts from Rasūlid-Yemen written in the 13th and 14th centuries mention the presence of vessels from Mogadishu visiting the southern port cities of Yemen. ‘According to al-Ašraf 'Umar, the ships of the Maqdišī left in the month of June/ḥazirān for Aden and left during the autumn. The ships of Maqdišū also went annually to al-Šiḥr and to the two small neighboring ports, Raydat al-Mišqāṣ and Ḥīyrīğ.’ They exported cotton fabrics with ornamented edges ( ğawāzī quṭn muḥaššā ) called “Maqdišū”; they also exported captives that were different from those obtained from the Zanj coast; and they sold commodities such as ebony (abanūs), amber ('anbar) and ivory ('āğ ) that were actually re-exported from the southern Swahili cities through the port of Barawa where “There is an anchorage (marsā) sought after by the boats (ḫawāṭif ) from India and from every small city of the Sawāḥil.”26

Curiously, while these Rasulid accounts include parts of Abyssinia (Ethiopia), Ḥiğāz (Western Arabia) and the Gulf in the list of all those who had pledged allegiance to the Yemeni sultan al-Muẓaffar Yūsuf (r. 1249–1295), Mogadishu and the rest of the East African coastal cities never entered the orbit of Rasūlid ambitions and interests. None of the accounts mentions any travel to the ‘Bilād al-Zanğ’ save for a few movements of scholars to this region. This indicates that contrary to the local claims of ties to Yemen by the dynasties of 13th century Kilwa and post-1500 Mogadishu (see below), this region was considered peripheral to Yemeni chroniclers.27

Mogadishu was one of the East African cities visited by the Chinese admiral Zheng He during his fourth (1413-1415) and fifth expedition (c. 1417–1419). Envoys sent from the city travelled with gifts which included zebras and lions that were taken to the Ming-dynasty capital in 1416 and returned home on the 5th expedition. The chronicler Fei Xin, who accompanied the third, fifth, and seventh expeditions of Zheng He as a soldier described the stone houses of Mogadishu, which were four or five stories high. “The native products are frankincense, gold coins, leopards, and ambergris. The goods used in trading [by the Chinese] are gold, silver, coloured satins, sandal-wood, rice, china-ware, and colored taffetas. The rich people turn to seafaring and trading with distant places.” Mogadishu had been mentioned in a number of Chinese texts since the 12th century, using information from secondary sources, and after Zheng He’s trip, it subsequently appeared more accurately on later Chinese maps.28

[ see my previous essay on ‘Historical contacts between Africa and China from 100AD to 1877’ ]

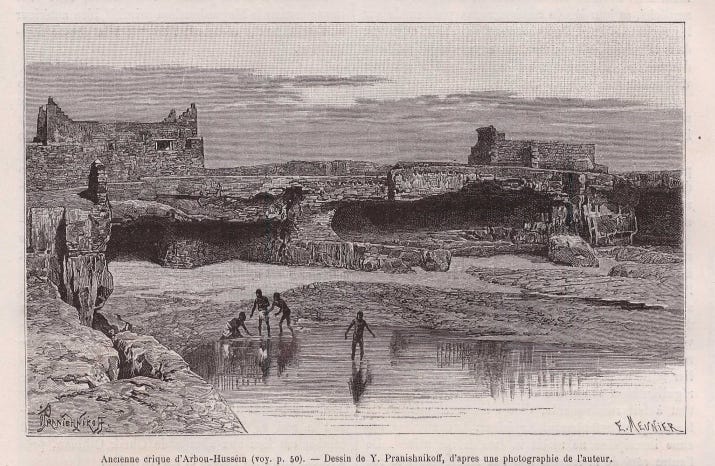

Pre-colonial port remains, ca. 1882. ‘In Mogadishu there is a remarkable memorial of work, which must have been undertaken for the public good, to be seen in the remains of an old harbour installation, almost a dry dock. Behind a small promontory, against which the surf constantly pounds, a basin about 30 metres square has been dug out of the solid coral; at the sides the rock has been hollowed out to allow small vessels to be drawn up; from these hollowed-out caves, a spiral staircase about eight metres deep has been bored through the rock, connecting the installation with the upper level. At ebb tide the whole basin is almost dry, but it appears that there was originally provision for sealing it off from the sea altogether, for the flood enters only through one narrow channel. On the other hand the difficulty of entry from the sea side makes it somewhat doubtful whether this dock could have been in constant and general use. Possibly it served as a refuge for a fortress on the rocky promontory, and as an emergency channel for ships in time of war. Whatever its uses it remains astonishing evidence of the creative activity of these earlier times.’29 [a slightly similar form of maritime architecture was constructed at Kilwa in the 13th-16th century]

Mogadishu during the 16th and 17th centuries: The Muzaffarid dynasty, the Portuguese, and the Ajuran empire.

The 16th century in Mogadishu was a period of political upheaval and economic growth, marked by the ascendancy of the Muzaffarid dynasty in the city, the Portuguese colonization of the Swahili coast, and the expansion of the Ajuran empire from the mainland of Southern Somalia.

Vasco Da Gama reached the city in 1499, and his description of Mogadishu mentions its muti-storey buildings and ‘lighthouse towers’ (actually minarets of mosques).30 On his return from his first voyage to India, Vasco da Gama bombarded the town, and despite repeated Portuguese claims that Mogadishu was amongst its vassals, this vassalage was never conceded. Attempts by the Portuguese to sack the city failed repeatedly in 1506, 1509, and 1541; the city at times mustered a cavalry force in some of these engagements.31 Mogadishu later appears in the list of East African cities whose merchants were encountered in Malacca by the Portuguese envoy Tome Pires in 1505.32

The description of the East African coast by the chronicler Joao De Barros in 1517 also includes a brief account of the city and its inhabitants:

“Proceeding coastwise towards the Red Sea there is a very great Moorish town called Magadoxo; it has a king over it; the place has much trade in divers kinds, by reason where of many ships come hither from the great kingdom of Cambaya, bringing great plenty of cloths of many sorts, and divers other wares, also spices; and in the same way they come from Aden. And they carry away much gold, ivory, wax and many other things, whereby they make exceedingly great profits in their dealings. In this country is found flesh-meat in great plenty, wheat, barley, horses and fruit of divers kinds so that it is a place of great wealth. They speak Arabic. The men are for the most part brown and black, but a few are fair. They have but few weapons, yet they use herbs on their arrows to defend themselves against their enemies.”33

Copper coins issued by the first ruler of the Muzaffarid dynasty of Mogadishu are thought to have been first struck around the year 1500, with the inscription: “The Sultan 'Umar, the King of the Muzaffar.” At least 7 of his successors would issue their own coins until the fall of the dynasty during the late 17th century. While many of these coins, which are undated, were found in the vicinity of Mogadishu where they circulated, a few were found in Barawa and as far south as Kisimani Mafia in Tanzania. The large number of coins issued by at least one of the Muzzafarid rulers —5,965 pieces belonging to Sultan Ali ibn Yusuf— point to a period of economic prosperity in Mogadishu driven by trade between its hinterland and the Indian Ocean world.34

copper-alloy coins of Ali Ibn Yusuf. Mogadishu, Somalia, British Museum.

photo captioned: ‘Ruins known as “Mudhaffar Palace, with cross vault (13th century), during the excavation campaign’35 ca. 1926-1928,

caption: ‘Picture from the early 1900s: the “Palace on the beach” is still buried and the area around it seems to have been an assembly point for the shipping of livestock’36 The old ruins are no longer visible.

Historical traditions regarding the Ajuran empire of southern Somalia indicate that Mogadishu fell within its political orbit, although it largely remained under the control of the Muzaffarids.37 The empire controlled much of the hinterland of Mogadishu as well as the interior trade routes and meeting points such as Afgooye. It was thus able to control considerable amounts of agricultural and pastoral wealth that were exported through Mogadishu, hence the appearance of interior commodities such as ivory, wax, and grain in 16th-century Portuguese descriptions of Mogadishu’s exports, as well as the presence of horsemen in the description of its armies, quite unlike the southern cities where horses were rare.38

In the late 16th century, Mogadishu became embroiled in the Ottoman-Portuguese conflict over the control of the western Indian Ocean, when the city welcomed the Turkish corsair Amir 'Ali Bey twice in 1585-6 and 1588. According to Portuguese accounts, Ali Bey would have pretended to impose himself that a great fleet dispatched by the Sultan himself would succeed him to subjugate the whole of the coast, rewarding the cities having made an act of allegiance and punishing the others. For fear that the city would be looted, Mogadishu's leaders submitted by offering tribute, and then accompanied Ali Bey in local boats, motivated by the promise of loot from the Portuguese colonies.39

After the defeat of Ali Bey's forces near Mombasa, the Ottomans quickly abandoned their interests in the region. Traditions from the southern cities such as Faza mention the continued presence of dynastic clans known as Stambul (or Stambuli ie: ‘from Istanbul’) who were said to be of Turkish origin and were originally settled in Mogadishu, from which they were expelled before settling in Barawa and then on the Bajun Islands. One such ‘Stambuli’ had been installed at Faza shortly after Ali Bey’s first expedition but he was killed during the massacre of the city’s inhabitants by the Portuguese.40

While the Portuguese re-established their control over the southern half of the East African coast, most of the northern half extending from Pate to Mogadishu remained under local authority. Mogadishu occasionally paid tribute to quieten the Portuguese but the town enjoyed virtual self-government. An account from 1624 notes that while the two northmost cities of Barawa and Mogadishu were at peace with the Portuguese, they did not accept their ships.41

The city of Pate was the largest along the northern half of the coast and was the center of a major commercial and intellectual renascence that was driven in part by the invitation of scholarly families from southern Yemen.

[see my previous article on ‘An intellectual revolution on the East African coast (17th-20th century)’]

These migrant families also appear in the epigraphic record at Mogadishu, represented by an epitaph from a tomb in the HamarWeyne quarter with the name Abu al-Din al-Qahtani, dated November 1607, and another on a wooden door with inlaid decoration from a house in Mogadishu, which names a one Sayyid Alawi and his family dated June 1736.42 According to traditions, the Qahtani Wa’il of Mogadishu were experts in judicial and religious matters and became the qadis of Mogadishu and khatibs of the mosque.43

Masjid Fakhr al-Din, ca. 1927-1929. ‘the twin ogival and pyramidal vaulted roof is its distinctive feature.’44

Mogadishu between the mid-17th century and late 18th century.

Beginning in the first half of the 17th century, the Muzaffarid dynasty of Mogadishu was gradually ousted by a new line of imams from the Abgaal sub-clan of the Hawiye clan family. The Abgaal imams and their allies mostly resided in the Shangani quarter of Mogadishu, but their power base remained in the interior. Members of the imam's lineage, which was known as Yaaquub, intermarried with the merchant families of the BaFadel and Abdi Semed and soon became renowned as abbaans (brokers) in the trade between the coast and interior. The Abgaal didn’t overrun the city but shared governance with the town’s ruling families.45

Later chronicles from Mogadishu occasionally reflect the intrusion into town life of various groups of Hawiye pastoralists who inhabited the hinterland. Gradually, the clans of the town changed their Arabic names for Somali appellatives. The ‘Akabi became rer-Shekh, the Djid’ati the Shanshiya, the ‘Afifi the Gudmana, and even the Mukri (Qhahtani) changed their name to rer-Fakih. 46

‘La grand Lab de Moguedouchou’ ca. 1885, image from ‘Mogadishu: Images from the Past’

Accounts from the mid-17th century mention that Mogadishu and the neighbouring towns of Merka and Barawa traded independently with small vessels from Yemen and India.47 Mogadishu traded with the shortlived sultanate of Suqutra in Yemen between 1600 to 1630, mainly exporting rice, mire (perfume), and captives from Madagascar., some of which were reexported to India, specifically to Dabhol and Surat. But this trade did not last long, as while Surat frequently received ships from Mogadishu in the 1650s, this direct shipping completely disappeared by 1680, and trade with the Swahili coast was confined to a few ships coming from Pate annually.48

In the later period, however, Mogadishu lost its commercial importance and fell into decline. There are a few fragmentary accounts about the now reduced town during this period, such as one by a French captain based at Kilwa in 1750-1760 who reported that Mogadishu and the rest of the coast were still visited by a few Arab vessels.49 Portuguese accounts that refer to the coast between Mogadishu and Berbera as “a costa de Mocha” (named after the Yemeni city) mention that the towns were visited by 4-5 ships annually from the Indian cities of Goga and Purbandar.50

A Dutch vessel arriving at Barawa from Zanzibar in 1776 refers to a message from Mogadishu to the King of Pate that informs the latter of a European shipwreck near Mogadishu, adding that the Swahili pilots of the Dutch ship recommended that they should avoid the town:

“Two vessels with white people had come to the shore but the water was so rough by the beach that both the barge and the boat were wrecked. All the whites were captured by the natives and murdered, with the exception of a black slave who had been with them and whose life was granted by the barbarians. Then they had pulled the vessels up and burned them, after taking out the cash, flintlocks, and other goods which were to be found in them, and then fled. Therefore we asked the natives and our pilots whether such evil and murderous peoples lived in Mogadiscu or further along the coast, and how the anchorages and water were in this wind! To this they unanimously answered that Mogadiscu was now inhabited by Arabs and a gathering of evil natives, and that no Moorish, let alone European, ships came there."51

According to the historian Edward Alpers, the Abgaal domination of Shangani left the older elite of HamarWeyne without significant allies in the interior. In the late 18th century, a man of the reer Faaqi (rer-Fakih) family in the HamarWeyne section established the interior town of Luuq inorder to link Mogadishu directly with the trade routes that extended into southern Ethiopia. This initiative may also reflect the general growth of trade at Zanzibar, which dates to the domination of the Busa’idi dynasty of Oman from 1785.52

‘Our dhow in the harbor of Moguedouchou’ ca. 1885. image from ‘Mogadishu: Images from the Past’

Mosque in the HamarWeyne section of Mogadishu, Somalia, ca. 1909, Archivio fotografico Società Geografica, Italy.

Mogadishu in the 19th century.

By the early 19th century Mogadishu and the two other principal towns of the Benaadir coast, Merka and Barawa, were trading small quantities of ivory, cattle, captives, and ambergris with boats plying the maritime routes between India, Arabia, Lamu, and Zanzibar. According to the account of Captain Thomas Smee obtained from two Somali informants in 1811, the town of Mogadishu “is not very considerable, may contain 150 to 200 [stone] houses, and has but little trade.” He was also informed that it was governed by '“a Soomaulee Chief named Mahomed Bacahmeen” who was probably the reigning Abgaal imam.53

The account of the British captain W. F. W. Owen about a decade later describes Mogadishu as an abandoned city well past its heyday:

“Mukdeesha, the only town of any importance upon the coast is the mistress of a considerable territory. . . At a distance the town has rather an imposing appearance, the buildings being of some magnitude and composed of stone. The eye is at first attracted by four minarets of considerable height, towering above the town, and giving it an air of stilly grandeur, but a nearer approach soon convinces the spectator that these massive buildings are principally the residences of the dead, while the living inhabit the low thatched huts by which these costly sepulchres are surrounded. It is divided into two distinct towns, one called Umarween, and the other Chamgany, the latter of which may with justice be called 'the city of the dead', being entirely composed of tombs. Umarween has nearly one hundred and fifty stone houses, built in the Spanish style, so as to enclose a large area. Most of the Arab dows visit this place in their coast navigation, to exchange sugar, molasses, dates, salt fish, arms, and slaves, for ivory, gums, and a particular cloth of their own manufacture, which is much valued by the people of the interior.”54

Owen's account provides the most detailed description of Mogadishu's two moieties, its local cloth industry, and the internal demand for imported captives which anteceded the rapid expansion of its commodities trade during the later half of the 19th century.

[see my previous article on ‘Economic growth and social transformation in 19th century Somalia’ ]

The Market Place in Mogadishu, ca. 1882

‘Spinning, sizing, and unwinding cotton at Moguedouchou’. ca. 1882.

Mogadishu soon attracted the attention of the Busaidi sultan of Zanzibar, Said, who bombarded the city into submission in 1828. This was followed by a period of social upheaval marked by a series of natural disasters and the rise of the Baardheere jamaaca movement in the interior which disrupted trade to the coast from 1836 until its defeat by the combined forces of the Geledi sultanate and its allies in mid-1843.55

A succession crisis in Mogadishu that pitted the Shangani and HamarWeyne moeties was briefly resolved by the Geledi sultan who controlled the hinterland. The sultan appointed a leader of the town and compelled the other to move inland, but the delicate truce quickly fell apart as the two moeties separated themselves physically by constructing a wall and gate, and building separate mosques. In the same year, Sultan Seyyid Said of Zanzibar appointed a local Somali governor over the town but tensions in the city forced him to quickly abandon his duties and flee for the interior.56

‘The fort (Garessa) of Mogadishu, with Fakr ad-Din Mosque and HamarWeyne on the left and Shangani on the right.’ image and caption by ‘Mogadishu: Images from the Past’

Visitors in 1843 described Mogadishu as a modest town of 3,000-5,000 inhabitants which was in a state of ruin. Its fortunes would soon be revived in the later decades driven by the growth of agricultural exports, and the Benaadir coast was referred to as ‘the grain coast of Southern Arabia.’

In the mid-1840s Seyyid Said replaced his first, ineffectual governor with a customs officer who was under the Indian merchant-house of Jairam Sewji. Later Zanzibari governors established themselves at a small fort built in the 1870s near the HamarWeyne section at the expense of the Shangani section, and formed an alliance with the Geledi sultan, allowing the Zanzibar sultan to exercise significant commercial influence on Mogadishu. This resulted in the expansion of credit into the ivory trade of the interior during the late 19th century, as well as the displacement of smaller local merchants with larger merchant houses from Zanzibar.57

At the close of the century, the competition between HamarWeyne and Shangani was further intensified during the colonial scramble. Zanzibar's sultan Khalifa had "ceded" the coastal towns to Italy in 1892, even though they were hardly his to cede. The Italians found little support in HamarWeyne but were less distrusted in Shangani, where a residence was built for the Italian governor in 1897. The coastal towns thereafter remained under the administration of a series of ‘Benaadir Company’ officials supported by a small contingent of Italian military officers, before the whole region was formally brought under effective control in 1905, marking the end of Mogadishu’s pre-colonial history and the beginning of its status as the capital of modern Somalia.58

The Jama’a mosque in 1910, image from Istituto Nazionale di Archeologia e Storia dell'Arte

Looking from Shangani to HamarWeyne

Like Mogadishu, the 19th century city of Zanzibar was a multicultural meltingpot, whose population was colorfully described by one visitor as “a teeming throng of life, industry, and idleness.”

The social history of Zanzibar and the origins of its diverse population are the subject of my latest Patreon article, please subscribe to read more about it here:

“ceramic collections from the excavations at the Shangani mosque do not challenge the central assertion by Chittick that there is no evidence for the existence of a town at Mogadishu before the late 12th century. On the contrary, the Shangani sequence as it now stands appears to extend back only to the 13th century.” The Origins and Development of Mogadishu AD 1000 to 1850: A Study of the Urban Growth Along the Benadir Coast of Southern Somalia by AD Jama pg 136

Medieval Authors about East Africa: Mogadishu, By Pieter Derideaux

Islam in East Africa by John Spencer Trimingham pg 5-6

Medieval Mogadishu by H.N. Chittick pg 50. ‘To the tribes of the Negroes belong also the Zendj or the Zaghouah, called after Zagou, son of Qofth b. Micr b. Kham; they are divided in two tribes, the Qabliet and the Kendjewiat, the first name means ants, the second dogs. Their capital is Maqdashou, where the merchants of all countries go. It owns the coast called Zenjebar, which has several kingdoms.’ quote from: Medieval Authors about East Africa: Al-Dimashqi, By Pieter Derideaux:

The East African Coast: Select Documents from the First to the Earlier Nineteenth Century by Greville Stewart Parker Freeman-Grenville pg 28, Islam in East Africa by John Spencer Trimingham pg 6)

The Benaadir Past: Essays in Southern Somali History by Lee Cassanelli pg 1-7, Horn and Crescent: Cultural Change and Traditional Islam on the East African Coast, 800-1900 by Randall L. Pouwels, pg 7-15, Swahili Origins: Swahili Culture & the Shungwaya Phenomenon By James De Vere Allen pg 44-52)

Excavations at Hamar Jajab unfortunately yielded little material culture that could be dated: The Origins and Development of Mogadishu AD 1000 to 1850: A Study of the Urban Growth Along the Benadir Coast of Southern Somalia by AD Jama pg 71-73, Medieval Mogadishu by H.N. Chittick pg 48-49

‘The ceramics found show, in some cases a very wide chronological span . A dating of the different rebuilding phases will be based on the youngest dateable sherds in the filling under the floor level. This means that the (oldest Shagani) mosque was erected …. after the year 1200 A.D. At the same time it can be noted that the oldest sherds of imported Arabic / Persian goods from (the Shagani) Mosque site seem to be dated to the eleventh century , and that these mainly appear in the fillings of the oldest layers.’

Taken from: Pottery from the 1986 Rescue Excavations at the Shangani Mosque in Mogadishu By Paul J. J, Sinclair. quote from: Medieval Authors about East Africa: Mogadishu, By Pieter Derideaux

The Origins and Development of Mogadishu AD 1000 to 1850: A Study of the Urban Growth Along the Benadir Coast of Southern Somalia by AD Jama pg 62- 120-137, Medieval Mogadishu by H.N. Chittick pg 54-60)

A Preliminary Handlist of the Arabic Inscriptions of the East African Coast by GSP Freeman-Grenville pg 102-104

The "Shirazi" problem in East African coastal history by James De Vere Allen pg 9-10)

Medieval Mogadishu by H.N. Chittick pg 53-54

This and other illustrations from 1882 are taken from “Voyage Chez Les Benadirs, Les Comalis et les Bayouns, par M.G. Revoil en 1882 et 1883”

M.G. Revoil, 1882, quote from: Medieval Authors about East Africa: Mogadishu, By Pieter Derideaux

The Portuguese Period in East Africa by Justus Strandes, edited by James S.. Kirkman, pg 78.

Historic Mosques in Sub-Saharan Africa: From Timbuktu to Zanzibar By Stéphane Pradines pg 233-234

The Travels of Ibn Battuta, A.D. 1325-1354: Volume II, trans./ed . by H.A.R. Gibb, pg 378, The Travels of Ibn Battuta, AD 1325-1354, Volume IV, trans./ed. by H.A.R. Gibb and C. F. Beckingham, pg 809

The Swahili: The Social Landscape of a Mercantile Society by Mark Horton, John Middleton pg 172)

Coins From Mogadishu, c.1300 to c. 1700 By GSP Freeman-Grenville

The Travels of Ibn Battuta, A.D. 1325-1354: Volume II, trans./ed . by H.A.R. Gibb, pg 374,

The Travels of Ibn Battuta, AD 1325-1354, Volume IV, trans./ed. by H.A.R. Gibb and C. F. Beckingham pg 865

A Traveller in Thirteenth-century Arabia: Ibn Al-Mujāwir's Tārīkh Al-mustabṣir by Yūsuf ibn Yaʻqūb Ibn al-Mujāwir

The Swahili: The Social Landscape of a Mercantile Society by Mark Horton, John Middleton pg 81-82

The Portuguese Period in East Africa by Justus Strandes, edited by James S. Kirkman, pg 73

The Scramble in the Horn of Africa; History of Somalia (1827-1977). by Mohamed Osman Omar pg 17-18

L'Arabie marchande: État et commerce sous les sultans rasulides du Yémen (626-858/1229-1454). By Éric Vallet, Chapitre 9, p. 541-623, Prg 28-31.

L'Arabie marchande: État et commerce sous les sultans rasulides du Yémen (626-858/1229-1454). By Éric Vallet, Chapitre 9, p. 541-623, Prg 33, The Worlds of the Indian Ocean: Volume 2, From the Seventh Century to the Fifteenth Century CE: A Global History by Philippe Beaujard pg 352-353

The Worlds of the Indian Ocean: Volume 2, From the Seventh Century to the Fifteenth Century CE: A Global History by Philippe Beaujard pg 462-467, China and East Africa by Chapurukha M. Kusimba pg 53-54, 109)

The Portuguese Period in East Africa by Justus Strandes, edited by James S. Kirkman, pg 73

The Portuguese Period in East Africa by Justus Strandes, edited by James S. Kirkman, pg 299

The Portuguese Period in East Africa by Justus Strandes, edited by James S. Kirkman, pg 27, 69, 98-99, 111-112

The East African Coast: Select Documents from the First to the Earlier Nineteenth Century by Greville Stewart Parker Freeman-Grenville pg 126)

The Book of Duarte Barbosa: An Account of the Countries Bordering on the Indian Ocean and Their Inhabitants, Issue 49, by Duarte Barbosa, Fernão de Magalhães, pg 31

Coins From Mogadishu, c.1300 to c. 1700 By GSP Freeman-Grenville pg 180-183, 186-195

Mogadishu and its urban development through history by Khalid Mao Abdulkadir, Gabriella Restaino, Maria Spina pg 33

Exploring the Old Stone Town of Mogadishu by Nuredin Hagi Scikei pg 47

The Shaping of Somali Society By Lee V. Cassanelli pg 104

The Shaping of Somali Society By Lee V. Cassanelli pg 112-113, The Origins and Development of Mogadishu AD 1000 to 1850 by Ahmed Dualeh Jama pg 88-89, The Benaadir Past By Lee V. Cassanelli pg 27-8

The Portuguese Period in East Africa by Justus Strandes, edited by James S. Kirkman, pg 128-134. Les cités-États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu, 1585-1810: dynamiques endogènes, dynamiques exogènes by Thomas Vernet pg 99, 108)

Les cités-États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu, 1585-1810: dynamiques endogènes, dynamiques exogènes by Thomas Vernet pg 101, n. 19, The Portuguese Period in East Africa by Justus Strandes, edited by James S. Kirkman, pg 131-132

Les cités-États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu, 1585-1810: dynamiques endogènes, dynamiques exogènes by Thomas Vernet pg 122, n. 107, Coins From Mogadishu, c.1300 to c. 1700 By GSP Freeman-Grenville pg 182)

A Preliminary Handlist of the Arabic Inscriptions of the East African Coast by GSP Freeman-Grenville pg 105

The Swahili: The Social Landscape of a Mercantile Society by Mark Horton, John Middleton pg 69)

Mogadishu and its urban development through history by Khalid Mao Abdulkadir, Gabriella Restaino, Maria Spina pg 44

The Shaping of Somali Society By Lee V. Cassanelli pg 73-74, 93,

The Shaping of Somali Society By Lee V. Cassanelli pg 100-101, The Scramble in the Horn of Africa; History of Somalia (1827-1977). by Mohamed Osman Omar pg 19

Muqdisho in the Nineteenth Century: A Regional Perspective by EA Alpers pg 442)

Arabian Seas: the Indian Ocean world of the seventeenth century By R. J. Barendse pg 34-35, 58, 215, 259

The French at Kilwa Island: An Episode in Eighteenth-century East African History by Greville Stewart Parker Freeman-Grenville pg 142

Arabian Seas, 1700-1763 by R. J. Barendse pg 325

The Dutch on the Swahili Coast, 1776-1778: Two Slaving Journals. by R Ross pg 344)

Muqdisho in the Nineteenth Century: A Regional Perspective by EA Alpers 442)

Muqdisho in the Nineteenth Century: A Regional Perspective by EA Alpers pg 444)

Muqdisho in the Nineteenth Century: A Regional Perspective by EA Alpers pg 444-445)

The Shaping of Somali Society By Lee V. Cassanelli pg 137-146

Muqdisho in the Nineteenth Century: A Regional Perspective by EA Alpers 445)

Muqdisho in the Nineteenth Century: A Regional Perspective by EA Alpers pg 446-454, The Shaping of Somali Society By Lee V. Cassanelli pg 175-176

Muqdisho in the Nineteenth Century: A Regional Perspective by EA Alpers pg 456, The Shaping of Somali Society By Lee V. Cassanelli pg 198-199, 201-205, The Scramble in the Horn of Africa; History of Somalia (1827-1977). by Mohamed Osman Omar pg 20, 246-247

As always Mondays is my favorite time on line because of your articles, much thanks.

I visited Mogadishu for a couple of days meetings with the US Embassy staff, including a drive down the coast and then to Bardera and back. I was told that the waters off of the beach were shark infested so the beach was only used by the local fishing boats.