A history of the medieval coastal towns of Mozambique ca. 500-1890 CE.

The East African coast is home to the longest contiguous chain of urban settlements on the continent. The nearly 2,000 miles of coastline which extends from southern Somalia through Kenya and Tanzania to Mozambique is dotted with several hundred Swahili cities and towns which flourished during the Middle Ages.

While the history of the northern half of the ‘Swahili coast’ has been sufficiently explored, relatively little is known about the southern half of the coast whose export trade in gold was the basis of the wealth of the Swahili coast and supplied most of the bullion sold across the Indian Ocean world.

From the town of Tungi in the north to Inhambane in the southern end, the coastline of Mozambique is home to dozens of trade towns that appeared in several works on world geography during the Islamic golden age and would continue to thrive throughout the Portuguese irruption during the early modern period.

This article outlines the history of the medieval coastal towns of Mozambique and their contribution to the ancient trade of the Indian Ocean world.

Map of Mozambique highlighting the medieval towns mentioned below1

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Foundations of a Coastal Civilization in Mozambique: ca. 500-1000CE.

Beginning in the 6th century, several coeval shifts took place along the East African coast and its immediate hinterland. Archaeological evidence indicates that numerous iron-age farming and fishing settlements emerged across the region, whose inhabitants were making and using a new suite of ceramics known as the ‘Triangular Incised Ware’ (TIW), and were engaged in trade between the Indian Ocean world and the African mainland. These settlements were the precursors of the Swahili urban agglomerations of the Middle Ages that appear in external accounts as ‘the land of the Zanj.’2

The greater part of the territory that today includes the coastline and hinterland of Mozambique was in the Middle Ages known as ‘the land of Sofala.’ Located south of the Zanj region, it first appears as the country of al-Sufālah in the 9th-century account of the famous Afro-arab poet Al-Jāḥiẓ.3

The coast of Sofala was later described in more detail in the geographical work of Al Masudi in 916: “The sea of the Zanj (Swahili coast) ends with the land of Sofala and the Waq-Waq, which produces gold and many other wonderful things” The account of the Persian merchant Buzurg ibn Shahriyar in 945, describes how the WaqWaq (presumed to be Austronesians) sailed for a year across the ocean to reach the Sofala coast where they sought ivory, tortoiseshell, leopard skins, ambergris and slaves. In 1030 CE, al-Bîrûnî writes that the port of Gujarat (in western India) “has become so successful because it is a stopping point for people traveling between Sofala and the Zanj country and China”.4

(left) A simplified copy of Al-Idrisi’s map made by Ottoman scholar Ali ibn Hasan al-Ajami in 1469, from the so-called “Istanbul Manuscript”, a copy of Al-Idrisi’s ‘Book of Roger.’ (right) Translation of the toponyms found on the simplified copy of al-Idrisi’s world map, showing Sofala between the Zanj and the Waq-Waq.

However, excavations at various sites in northern Mozambique revealed that its coastal towns significantly predated these external accounts. The oldest of such settlements was the archaeological site of Chibuene where excavations have revealed two occupational phases; an early phase from 560 to 1300 CE, and a later phase from 1300–1700 CE. Another site is Angoche, where archaeological surveys date its earliest settlement phases to the 6th century CE.

The material culture recovered from Chibuene included ceramics belonging to the ‘TIW tradition’ of the coastal sites and the ‘Gokomere-Ziwa tradition’ found across many iron-age sites in the interior of southeast Africa. It also contained evidence of lime-burning similar to the Swahili sites (albeit with no visible ruins); a crucible with a lump of gold likely obtained from the Zimbabwe mainland; as well as large quantities of imported material such as glass vessels and beads, green-glazed ware and sgraffito from Arabia and Siraf.5

Chibuene gradually lost its prominence after 1000CE, as trade and/or settlement shifted to Manyikeni, a ‘Zimbabwe tradition’ stone-walled settlement situated 50 km inland, and possibly further south near Inhambane, where a site with earthenwares similar to those at Chibuene but without any imports, has been dated to the 8th century.6 Chibuene likely became tributary to Manyikeni, as indicated by later written documents which suggest that the lineage of Sono of Manyikeni controlled its coastal area, and the presence of pottery in the later occupation in Chibuene that is similar to the ceramics found at Manyikeni.7

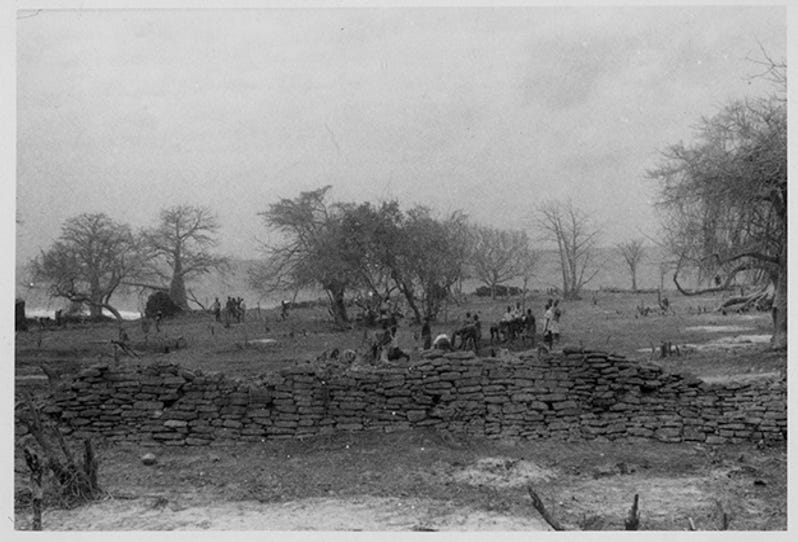

Manyikeni ruins in the mid-20th century. image reproduced by Eugénia Rodrigues

Manyikeni ruins, images from Facebook.

To the north of Chibuene was the early settlement at Angoche, which consists of a cluster of sites on several islands that contain ceramics of the ‘TIW tradition’ dated to the second half of the 1st millennium CE, as well as imported pottery from Arabia and the Gulf. In the period from 1000-1500CE, settlement expanded with new sites that contained local ceramics of the ‘Lumbo tradition’ (similar to Swahili pottery from Kilwa) and imported wares from the Islamic world and China. Around 1485-90 CE, Angoche was occupied by royals from Kilwa who settled at the sites of Quilua and Muchelele, according to the Kilwa chronicle and local traditions. There's evidence for coral limestone construction and increased external trade at several sites that now comprised the ‘Angoche Sultanate’ just prior to the arrival of the Portuguese.8

Further north of Angoche are the settlements of the Quirimbas archipelago, which stretches about 300 km parallel to the coast of northern Mozambique.

Map of the Quirimbas islands by Marisa Ruiz-Galvez et. al.

One early settlement found in this region was the site C-400 at Ibo, which contained local pottery similar to the ‘Lumbo tradition’, it also contained; bronze coins similar to those found at Kilwa; imported sherds from the gulf dated to between the 8th and the 13th centuries; glass-beads from India; and many local spindle-whorls, which confirms the existence of textile activity described by the Portuguese in their first reports of the Quirimbas archipelago. A locally manufactured gold bead found at Ibo also points to its links with the Zambezi interior and the Swahili coast. The assemblage of materials indicates a date of the 11th and 12th centuries CE.9

Further north in Mozambique's northernmost district of Palma, the sites of Tungui/Tungi, Kiwiya and Mbuizi also provided evidence for early settlement. Archaeological surveys recovered pottery belonging to different traditions, beginning with Early Iron Age wares (3rd-6th century CE), 'upper Kilwa' wares, and ‘Lumbo Tradition’ wares (after the 13th century) and recent Makonde pottery (15th-19th century). The three sites also contained imported ceramics from the Islamic world and China, glass beads, and remains of coral-stone structures from later periods.10

Ruins of a mosque at Tungi, northern Mozambique. image by Leonardo Adamowicz.

The historical period in Mozambique: on the coast of Sofala (1000-1500CE)

The archaeological evidence outlined above therefore indicates that the urban coastal settlements of late medieval Mozambique gradually emerged out of pre-existing farming and fishing villages that were marginally engaged in regional and long-distance trade, much like their Swahili peers in the north. It also indicates that there were multiple settlements along the coast —rather than a single important town of Sofala as is often presumed, and that the region later became an important part of the Indian Ocean trade.

The aforementioned account of Al-Idrīsī for example, described the voyages of people from the Comoros and Madagascar to the Sofala coast in order to acquire iron and gold: “The country of Sofāla contains many iron mines and the people of the islands of Jāvaga [Comorians] and other islanders around them come here to acquire iron, and then export it throughout India and the surrounding islands. They make large profit with this trade, since iron is a very valued object of trade, and although it exists in the islands of India and the mines of this country, it does not equal the iron of Sofala, which is more abundant, purer and more malleable.” The account of Ibn al-Wardī in 1240 reiterates this in his section on the Sofala coast: “The Indians visit this region and buy iron for large sums of silver, although they have iron mines in India, but the mines in the Sofala country are of better quality, [the ore being] purer and softer. The Indians make it purer and it becomes lumps of steel.”11

According to the account of Abu Al-Fida (d. 1331), who relied on earlier sources, the capital of Sofala was Seruna where the king resided. “Sofala is in the land of the Zanj. According to the author of the Canon, the inhabitants are Muslims. Ibn Said says that their chief means of existence are mining gold and iron.” He also mentions other towns such as Bantya, which is the northernmost town; Leirana, which he describes as “a seaport where ships put and whence they set out, the inhabitants profess Islam,” and Daghuta which is “the last one of the country of Sofala and the furthest of the inhabited part of the continent towards the south.”12

The globe-trotter Ibn Battuta, who visited Kilwa in 1331, also briefly mentioned the land of Sofala in his description of the city of Kilwa: “We set sail for Kilwa, the principal town on the coast, the greater part of whose inhabitants are Zanj of very black complexion. Their faces are scarred, like the Limiin at Janada. A merchant told me that Sofala is halfa month’s march from Kilwa, and that between Sofala and Yufi in the country of the Limiin is a month’s march. Powdered gold is brought from Yufi to Sofala.”13 Yufi was a site in the interior, identified by historians to be Great Zimbabwe, where gold was collected and dispatched to the coast. The coast/town of Sofala which Ibn Battuta mentioned must have been within Kilwa’s political orbit.14

The Kilwa chronicle, which was written around 1550, mentions that Kilwa's sultans had in the late 13th century managed to assume loose hegemony over large sections of its southern coast, likely encompassing the region of Sofala. The chronicle describes the sultan Ḥasan bin Sulaymān as “lord of the commerce of Sofala and of the islands of Pemba, Mafia, Zanzibar and of a great part of the shore of the mainland” The 14th century Sultan al-Hasan bin Sulaiman is known to have issued coins with a trimetallic system (gold, silver, and copper), one of these coins was found at Great Zimbabwe, which, in addition to the coins found near Ibo, provide evidence of direct contact between the Swahili coast, the coast of Sofala and interior kingdoms of the Zambezi river.15

Ruins of the Husuni Kubwa Palace of the 14th-century ruler of Kilwa Ḥasan bin Sulaymān. image by National Geographic

gold coins of the Kilwa Sultan Hassan bin Sulayman from the 14th century. image by Jason D. Hawkes and Stephanie Wynne-Jones

The location of Kilwa and the southern towns of Angoche and Sofala

According to oral traditions and written accounts, the emergence of the sultanate of Angoche is associated with the arrival of coastal settlers from Kilwa in 1490, and the expansion of the Indian Ocean trade with the coast of Sofala. The 15th-century account of sailor Ibn Majid mentions that “The best season from Kilwa to Sufāla is from November 14 to January 2, but if you set out from Sufāla, you should do it on May 11.” Sufala means shoal in Arabic, most likely because its reefs and islands were reported as a navigational hazard by sailors.16

On the other hand, Angoche is derived from ‘Ngoji,’ the local name for the city as known by its Koti-Swahili inhabitants which means ‘to wait’. Historians suggest Angoche was a port of call where merchants ‘waited’ until goods coming from the Zambezi interior via the region of Sofala arrived or they awaited permission to proceed further south. Angoche’s use as a port of call can be seen in a 1508 account, when the Portuguese captain Duarte de Lemos anchored by “an island that lies at the mouth of the river Angoxe [Angoche] and gathered freshwater supplies from a welcoming village.”17

The region of Sofala was thus the main hub of trade along the coastline of Mozambique during the late Middle Ages acting as the middleman in the trade linking the interior kingdoms like Great Zimbabwe and Swahili cities like Kilwa. Its reputation as a major outlet of gold is corroborated by the account of Ibn al-Wardi (d.1349) who wrote that the land of Sofala possessed remarkable quantities of the precious metal: “one of the wonders of the land of Sofala is that there are found under the soil, nuggets of gold in great numbers.”18

Gold objects from different ‘Zimbabwe tradition sites’: (first image) golden rhinoceros (A) and gold anklet coils (B) from Mapungubwe, South Africa, ca 13th century19; (second image) gold beads and gold wire armlet, ca. 14th-15th century, Ingombe Ilede, Zambia.20 (last image) Gold and carnelian beads from Ibo in the Quirimbas islands, ca. 10th-12th century CE. Archeometallurgical analysis showed a remarkable similarity between the gold bead of Ibo and the ones found at Mapungubwe.21

However, unlike the large cities of the Swahili coast, the towns on the coastline of Mozambique remained relatively small until the late Middle Ages, they were also less permanent, less nucleated and the largest boasted only a few thousand inhabitants.

It was during this period that a town known as Sofala emerged in the 15th century. Excavations at four sites around the town recovered material culture that includes local pottery still used in the coastal regions today, regional pottery styles similar to those found in southern Zambezia, and imported pottery from China dated to between the 15th and 18th centuries. Finds of elite tombs for Muslims, spindle whorls for spinning cotton, and small sherds of Indian pottery point to its cosmopolitan status similar to other Swahili towns, but with a significant local character, that's accentuated by finds of an ivory horn that bears some resemblance with those made on the Swahili coast and at Great Zimbabwe.22

15th/16th-century Ivory horn from the Swahili settlement at Sofala, and a similar horn from the Swahili city of Pate in Kenya.23

The Mozambique coast and the Portuguese during the 16th to 18th centuries

At the time of the Portuguese arrival in the Indian Ocean, the coastline of Mozambique was at the terminus of the main trade routes in the western half of the Indian Ocean world.

The Portuguese sailors led by Vasco Da Gama sailed past Sofala and landed on Mozambique island in January 1498, whose town was also established in the 15th century and was ruled by sultan Musa bin Bique (after whom the town was named). A contemporary chronicler described the city as such: “The men of this land are russet in colour (ie: African/Swahili) and of good physique. They are of the Islamic faith and speak like Moors. Their clothes are of very thin linen and cotton, of many-coloured stripes, and richly embroidered. All wear caps on their heads hemmed with silk and embroidered with gold thread. They are merchants and they trade with the white Moors (ie: Arab), four of whose vessels were here at this place, carrying gold, silver and cloth, cloves, pepper and ginger, rings of silver with many pearls, seed pearls and rubies and the like.”24

Ruined structure on the Swahili settlement at Mozambique island, dated to the 15th-16th centuries, image by Diogo V. Oliveira

After receiving information about golden Sofala from his first voyage, Vasco DaGama landed at the port town in 1502, followed shortly after by Pero Afonso in 1504. Both sent back laudatory reports on its wealth and its legendary status as King Solomon's Ophir, which prompted Portugal to send a military expedition to colonize it and Kilwa. In 1505, Captain Pero de Anhaia made landfall at Sofala and was generously received by its ruler, Sheikh Yusuf, who granted them permission to build a stockade (fortress of wood), probably because they had learned the fate of their peers in other Swahili cities like Kilwa that had been sacked for resisting the Portuguese.25

Like most of the towns described on the coast (including Sofala and Angoche), Sheikh Yusuf's Sofala was a modest town of a few thousand living in houses of wood, whose population included about 800 Swahili merchants who wore silk and cotton robes, carried scimitars with gold-decorated ivory handles in their belts, and sat in council/assembly that governed the town (like on the Swahili coast, the so-called “sultans” in this region were often appointed by these councils). The rest of the population consisted of non-Muslim groups who formed the bulk of the army, they wore cotton garments and copper anklets made in the interior.26

The Portuguese soon fell into conflict with the Sheikh after their failed attempts to monopolize Sofala's gold trade. These conflicts forced local merchants to divert the gold trade overland through the newly established town of Quelimane at the mouth of the Zambezi. This gold was then carried to Angoche in the north, ultimately passing through the Quirimbas islands, and onwards to Kilwa. Political and commercial links across these cities were sustained through kinship ties and intermarriages between their ruling dynasties, such as those between the sultans of Angoche and Kilwa. Additionally, in 1514 the Portuguese geographer Barbosa wrote that Mozambique island was frequented by the “Moors who traded to Sofala and Cuama [the Zambesi] [. . .] who are of the same tongue as those of Angoya [Angoche],” and he later wrote about the local Muslims of Quelimane that “these Moors are of the same language and customs as those of Angoya [Angoche].”27

Dhows in Harbour, ca. 1896, Mozambique, private collection.

According to a Portuguese account from 1506, at least 1.3 million mithqals of gold were exported each year from Sofala, and 50,000 came from Angoche, which translates to about 5,744 kg of gold a year. Other more detailed accounts estimate that from an initial 8,500kg a year before the Portuguese arrival, exports from the Sofala coast fell to an estimated 573kg in 1585; before gradually rising to 716kg in 1591; 850kg in 1610; 1487kg in 1667. Another account provides an estimate of 850kg in 1600, and 1,000kg in 1614. These figures fluctuated wildly at times due to “smuggling,” eg in 1512 when the Portuguese exported no gold from Sofala, but illegal trade amounted to over 30,000 mithqals (128kg) passing through northern towns like Angoche.28

[For a more detailed account of the gold trade between Great Zimbabwe, Sofala and Kilwa, please read this essay on Patreon]

The wild fluctuations in the gold trade were partially a result of the Portuguese wars against the coastal cities of Mozambique and Swahili. Sofala had been sacked in 1506, Angoche was sacked in 1511, and the towns of the Quirimbas islands were sacked in 1523. Each time, the local merchants returned to rebuild their cities and continued to defy the Portuguese. While large Portuguese forts were constructed at Sofala in 1507 and at Mozambique island in 1583, the two Swahili towns remained autonomous but were commercially dependent on the Portuguese trade.29

Ruins of the Portuguese fort at Sofala, late 19th-early 20th century, Yale University Library.

Mozambique island became an important port of call, at least 108 of the 131 Portuguese ships that visited the East African coast wintered at its port. By the early 17th century, the Portuguese settlement next to the fort had a population of about 2,000, only about 400 of whom were Portuguese. However, the fort was weakly defended with just 6 soldiers when the Dutch sacked the town in 1604 and 1607. While the Swahili rulers of Mozambique had been forced to move their capital to the mainland town of Sancul in the early 16th century, about half the island was still inhabited by the local Muslim population until at least the 18th century, and was referred to as ‘zona de makuti’. Both the Portuguese settlement and the mainland town of Sancul depended on the Makua rulers of the African mainland, from whom they obtained supplies of ivory and food, security, and captives who worked in their households.30

Angoche, Quilemane, and the Quirimbas were initially largely independent of the Portuguese. According to an account by Antonio de Saldanha in 1511, Angoche had an estimated population of 12,000, with atleast 10,000 merchants active in the interior. While these figures are exaggerated, they reflect the importance of the city and place it among the largest Swahili cities of the 16th century.

Around 1544, the sultan of Angoche leased the port of Quelimane to the Portuguese. Internal dissensions among the ruling families led to the Portuguese obtaining control of the sultanate in the late 16th century, coinciding with the founding of colonial ‘prazos’ (land concessions) along the Zambezi River and the Portuguese colonization of the kingdom of Mutapa. Angoche's population fell to about 1,500 in the early 17th century, and the Portuguese formally abandoned Angoche in 1709 when its trade dwindled to insignificance. By 1753, part of the city was rebuilt and its trade had slightly recovered, mostly due to trade with the Imbamella chiefs of the Makua along the coast.31

The East African coast showing the location of Angoche and the colonial prazos of the Portuguese. Map by Edward Pollard et al.

The era of Portuguese control in Sofala from the late 16th to the mid-18th century was also a period of decline, like in Angoche.

The fort was in disrepair and its trade consisted of small exports of ivory, and gold. A report from 1634 notes that the Sofala community resided near the fort by the indulgence of the ruler of Kiteve, whose kingdom surrounded the settlement and controlled its trade. In 1722, the Portuguese population at Sofala had fallen to just 26 settlers, a few hundred Luso-Africans, and other locals, the fort was threatened by inundation and the church was even being utilized as a cattle kraal. By 1762, Sofala was nearly underwater, and the garrison at the fort numbered just 6 soldiers. Estimates of Gold exports from Sofala, which averaged 300-400kg a year between 1750 and 1790, plummeted to just 10kg by 1820. In October 1836, Sofala was sacked by the armies of the Gaza empire from the interior, and by 1865 its inhabitants ultimately abandoned it for the town of Chiloane, 50 miles south.32

Further north in the Quirimbas islands, 16th-century Portuguese mention its thriving textile industry that produced large quantities of local cotton and silk cloth. These fabrics were coveted in Sofala and as far north as Mombasa and Zanzibar, whose merchants sailed southwards to purchase them. Accounts from 1523 and 1593 indicate that the rival rulers of Stone Town (on Zanzibar island) and Mombasa claimed suzerainty over parts of the archipelago. The Portuguese later established prazos on the islands, especially in the thriving towns of Ibo and Matemo, by the 17th century and began exporting grain, livestock, and ivory purchased from the interior to sell to Mozambique island.33

In his description of Mozambique written in 1592, Joao dos Santos makes reference to a large Swahili settlement on the island of Matemo with many houses with their windows and doors decorated with columns, that was destroyed by the Portuguese during the conquest of the archipelago. The present ruins of the mosque and other structures found at the site date to this period.34

Remains of a miḥrāb in the ruined mosque of Matemo, Quirimbas islands. image by Jorge de Torres Rodríguez et al. “Goods appear to have been left in the miḥrāb niche in a reverential manner. The local significance imparted on the mosque was possibly why the miḥrāb was targeted and partially destroyed in early 2018 by Islamists who likely viewed such actions as ‘shirk’ ie: idolatry.”35

In the 18th century, the islands served as a refuge for elites from Kilwa and Malindi who were opposed to the Omani-Arab occupation of the East African coast. By the late 18th century, the Quirimbas and Mozambique islands were at the terminus of trade routes from the interior controlled by Yao and Makua traders who brought ivory, grain, and captives, the former two of which were exported to the Swahili coast and the Portuguese, while the later were taken to the French colonies of the Mascarenes island. However, this trade remained modest before the 19th century when it expanded at Ibo, because Portuguese control of the islands was repeatedly threatened by attacks from the Makua during the 1750s and 60s, whose forces were active from Angoche in the south to Tungi in the north.36

From 1800 to 1817, the towns of Ibo, Sancul, and Tungui/Tungi were repeatedly attacked by the navies of the Sakalava from Madagascar, who were raiding the East African coast. I covered this episode of African naval warfare in greater detail here.

Tungi was the northernmost town along the coast, whose foundation was contemporaneous with the other ancient settlements as described in the introduction, but little is known about its early history save for a brief mention of its northern neighbor of Vamizi in the 15th-century account of Ibn Majid, and in conflicts with the Portuguese during the 1760s.37

Local chronicles and traditions attribute the “founding” of its sultanate to three princesses* from Kilwa who established ruling lineages that retained the ‘shirazi’ nisba used by the rulers of Kilwa during the Middle Ages and the 18th century. Known rulers begin with Ahmadi Hassani in the late 18th century, who was succeeded by five rulers between 1800-1830, followed by one long-serving ruler named Muhammadi (1837-1860), who was then succeeded by Aburari, whose dispute with his uncle Abdelaziz led to the Portuguese colonization of the island in 1877.38

[* Just like in the medieval cities of Comoros, the traditions about shirazi princesses as founding ancestresses of Tungi were an attempt to reconcile the matrilineal succession of the local groups with the patrilineal succession of the Islamized Swahili]

Location of the northernmost towns of Tungi, Mbuizi, and Kiwiya. Map by Nathan Joel Anderson.

Ruins of the Tungi palace. image by Nathan Joel Anderson. The palace consists of nine narrow rooms, connected via an axial hallway and a combination of arched and squared doorways, with one exit, and an upper story.39

In external accounts, Tungi briefly appears during the Sakalava naval invasions of the East African coast that began in 1800, the different titles used for its leader represent the varying relationship it had with the Portuguese, as it considered itself independent of their authority.

A Portuguese account from Ibo, which mentions the arrival of a flotilla from Mayotte (in Comoros) that intended to attack an unnamed king, also mentions that the Tungi ‘chief’ had expelled a group of boatmen from Madagascar, who were waiting for the monsoon winds to sail back to their land. The historian Edward Alpers suggests these two events were related, especially since Tungi was later the target of a massive Sakalava invasion that devastated the island in 1808-9. However, a later Sakalava invasion in 1815 was soundly defeated by Bwana Hasan, the ‘governor’ of Tungi, and another invasion in 1816 was defeated by the Portuguese at Ibo. An invasion in 1817 devastated Tungi, then ruled by a ‘King’ Hassan, before the navy of Zanzibar ultimately put an end to the Sakalava threat in 1818.40

Archaeological surveys indicate that most of the old town of Tungi was built in the 18th and 19th centuries, based on the age of the type of Chinese pottery found across the site. This includes the ruins of the old mosque, the sultan's palace, the town wall, most of the tombs, and the structures found in many of the outlying towns in the coastal region of the Palma district such as Kiwiya and Mbuizi.41 Tungi’s political links with Kilwa and the Swahili coast, and its dispersed nature of settlement (the site is 2km long), likely indicate that the town may have served as a port of call for the merchants of Kilwa during the 18th and 19th centuries, similar to Angoche during the 16th century.

(top) ruins of the Tungi mosque; (bottom) ruins of the town wall and sultan’s palace. images by Leonardo Adamowicz

The coastal towns of Mozambique during the 19th century

Trade and settlement along the northern coast of Mozambique during the 18th and 19th centuries were mostly concentrated at Tungi, Mozambique island, and at Ibo in the Quirimbas islands. The southern towns of Angoche and Sofala were gradually recovering from the decline of the previous period and had since been displaced by the rise of the towns of Quelimane and Inhambane much further south.

The 15th-century town of Quelimane, whose fortunes had risen and fallen with the gold trade from Angoche, was home to a small Portuguese fort and settlement since the 1530s. However, the town did not immediately assume great importance for the Portuguese and had less than three Portuguese families in the town by the 1570s. Its hinterland was home to many Makua chieftains and its interior was controlled by the Maravi kingdom of Lundu, whose armies often attempted to conquer the town during the early 17th century. This compelled local Makua chieftains and Muslim merchants to ally with the Portuguese, resulting in the latter creating prazos owned by the few settlers who lived there. These were in turn surrounded by a larger settlement populated by the Makua and Muslim traders.42

By the late 18th century, about 20 Portuguese lived at Quelimane with several hundred Africans surrounded by farms worked by both free peasants and captives from the interior, although most of the latter were exported. The town began to enjoy unprecedented prosperity based on the development of rice agriculture to supply passing ships. In 1806 an estimated 193,200 liters of rice (about 250 tonnes) and 82,800 liters of wheat (about 100 tonnes) were exported. After the banning of the slave trade in the Atlantic in 1817-1830, a clandestine trade in captives was directed through Quelimane; rising from 1,700 in 1836 to 4,900 in 1839, before declining to 2,000 in 1841 and later collapsing by the 1860s. It was replaced by 'legitimate trade' in commodities like sesame (about 500 tonnes in 1872) and groundnuts (about 900 tonnes in 1871).43

section of the Old Town of Quelimane, Mozambique, ca. 1914, DigitaltMuseum.

South of Quelimane was the town of Inhambane, which was the southernmost trade settlement encountered by the Portuguese during the early 16th century, although a latter account from 1589 mentions another settlement further south at Inhapula. The settlement at Inhambane was inhabited by Tonga-speakers, possibly as far back as the heyday of Chibuene (see introduction). It had a local cotton spinning and weaving industry for which it became well-known and was engaged in small-scale trade with passing ships. This trade remained insignificant until around 1727, when trade between local Tonga chiefs and the Dutch prompted the Portuguese to sack the settlement and establish a small fort. In the mid-18th century, the expansion of Tsonga-speaking groups from the interior, followed by the Nguni-speakers pushed more Tonga into the settlement and led to the opening of a lucrative trade in ivory and other commodities.44

Migrations of the Nguni and the Gaza ‘empire’. Map by M.D.D. Newitt.

During the 19th century, much of the southern interior of Mozambique was dominated by the Gaza Kingdom/‘empire,’ a large polity established by King Soshangane and his Nguni-speaking followers. The empire expanded trade with the coast, but the towns of Sofala and Inhambane remained outside its control, even after the former was sacked by Gaza's armies in 1836 and the latter in 1863. The empire later fragmented during the late 1860s after a succession dispute, around the same time the colonial scramble for Africa compelled the Portuguese to “effectively” colonize the coastal settlements.45

By the middle of the 1880s, the Portuguese had assumed formal control of the coastal towns from Inhambane to Tungi, and much of their prazos in the interior up to Tete. They then sent a colonial resident to the capital of the last Gaza king Gungunhana in 1886, who represented the last major African power in the region. The king initially attempted to play off the rivaling British and Portuguese against each other, and even sent envoys to London in April 1891. However, in June 1891 Britain and Portugal finally concluded a treaty recognizing that most of Gaza territory lay within the Portuguese frontiers.46

After 4 years of resistance, the empire fell to the Portuguese becoming part of the colony of Mozambique, along with the ancient coastal towns. The last independent sultan of the coastal towns died at Tungi in 1890, formally marking the end of their pre-colonial history.

Inscribed plaque of Sultan Muhammad ca. 1890, Tungi. Image by Nathan Joel Anderson

Mozambique island, ca. 1880, image by Dr. John Clark.

Among the most widely dispersed internal diasporas in Africa is the Rwandan-speaking diaspora of East Africa, whose communities can be found across a vast region from the eastern shores of Lake Victoria to the Kivu region of D.R.Congo. Their dramatic expansion during the 19th century was driven by opportunities for economic advancement and the displacement of local elites by the expansion of the Rwanda kingdom.

The history of the Rwandan diaspora in East Africa from 1800-1960 is the subject of my latest Patreon article, please subscribe to read more about it here:

Map by Leonardo Adamowicz

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria Jean LaViolette pg 8

The Worlds of the Indian Ocean: Volume 2, From the Seventh Century to the Fifteenth Century CE: A Global History by Philippe Beaujard pg 379

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria Jean LaViolette pg 370, 181, 372)

Trade and society on the south-east African coast in the later first millennium AD: the case of Chibuene by Paul Sinclair, Anneli Ekblom and Marilee Wood

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria Jean LaViolette pg 176-181, The Archaeology of Africa: Food, Metals and Towns by Bassey Andah, Alex Okpoko, Thurstan Shaw pg 419, 431.

Land use history and resource utilisation from A.D. 400 to the present, at Chibuene, southern Mozambique by Anneli Ekblom et al., pg 18

Settlement and Trade from AD 500 to 1800 at Angoche, Mozambique by E Pollard. The Early History of the Sultanate of Angoche by MDD Newitt pg 398)

The Swahili occupation of the Quirimbas (northern Mozambique): the 2016 and 2017 field campaigns. by Marisa Ruiz-Gálvez, Archaeometric characterization of glass and a carnelian bead to study trade networks of two Swahili sites from the Ibo Island (Northern Mozambique) by Manuel García-Heras et al, Quirimbas islands (Northern Mozambique) and the Swahili gold trade By Maria Luisa Ruiz-Gálvez and alicia perea

Archaeological impact assessment conducted for the proposed Liquefied Natural Gas project in Afunji and Cabo Delgado peninsulas, Palma district By Leonardo Adamowicz pg 27-37

The Worlds of the Indian Ocean: Volume 2, From the Seventh Century to the Fifteenth Century CE: A Global History by Philippe Beaujard pg 354, 368)

The East African Coast: Select Documents from the First to the Earlier Nineteenth Century by Greville Stewart Parker Freeman-Grenville pg 23-24)

The East African Coast: Select Documents from the First to the Earlier Nineteenth Century by Greville Stewart Parker Freeman-Grenville pg 31)

The African Lords of the Intercontinental Gold Trade Before the Black Death: al-Hasan bin Sulaiman of Kilwa and Mansa Musa of Mali by J. E. G. Sutton pg 232-233)

The Worlds of the Indian Ocean: Volume 2, From the Seventh Century to the Fifteenth Century CE: A Global History by Philippe Beaujard Vol2 pg 359-360, A Material Culture: Consumption and Materiality on the Coast of Precolonial East Africa by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 59-68,

The Worlds of the Indian Ocean: Volume 2, From the Seventh Century to the Fifteenth Century CE: A Global History by Philippe Beaujard Vol2 pg 12, Settlement and Trade from AD 500 to 1800 at Angoche, Mozambique by E Pollard. The Early History of the Sultanate of Angoche by MDD Newitt pg 446

The Early History of the Sultanate of Angoche by MDD Newitt pg 445

The Quest for an African Eldorado: Sofala, Southern Zambezia, and the Portuguese, 1500-1865 by Terry H. Elkiss pg 7-8

Dating the Mapungubwe Hill Gold by S. Woodborne, M. Pienaar & S. Tiley-Nel

Gold in the Southern African Iron Age by Andrew Oddy

Quirimbas islands (Northern Mozambique) and the Swahili gold trade by Marisa Ruiz-Galvez

The Archaeology of the Sofala coast by RW Dickinson pg 93-103, An Ivory trumpet from Sofala, Mozambique by BM Fagan

An Ivory Trumpet from Sofala, Mozambique by BM Fagan

Empires of the Monsoon by Richard Seymour Hall pg 161-164, Mozambique Island, Cabaceira Pequena and the Wider Swahili World: An Archaeological Perspective by Diogo V. Oliveira pg 7-12, Mozambique Island: The Rise and Decline of an East African Coastal City, 1500-1700 by M Newitt pg 23-24

The Quest for an African Eldorado: Sofala, Southern Zambezia, and the Portuguese, 1500-1865 by Terry H. Elkiss pg 14-17, A History of Mozambique By M. D. D. Newitt pg 18

The Archaeology of the Sofala coast by RW Dickinson pg 93-103, An Ivory trumpet from Sofala, Mozambique by BM Fagan pg 84-85

A History of Mozambique By M. D. D. Newitt pg 10-20, Mozambique Island: The Rise and Decline of an East African Coastal City, 1500-1700 by M Newitt pg 23)

Port Cities and Intruders: The Swahili Coast, India, and Portugal in the Early Modern Era by Michael N. Pearson pg 49-51

The Early History of the Sultanate of Angoche By M. D. D. Newitt pg 401-402, Mozambique Island: The Rise and Decline of an East African Coastal City, 1500-1700 by M Newitt 25, 29-30)

Mozambique Island: The Rise and Decline of an East African Coastal City, 1500-1700 by M Newitt 26-27, 30-34)

The Early History of the Sultanate of Angoche by MDD Newitt pg 402-406)

The Quest for an African Eldorado: Sofala, Southern Zambezia, and the Portuguese, 1500-1865 by Terry H. Elkiss pg 46-50, 54-55, 58, 63-67, See gold estimates in : Drivers of decline in pre‐colonial southern African states to 1830 by Matthew J Hannaford

Quirimbas islands (Northern Mozambique) and the Swahili gold trade by Marisa Ruiz-Galvezpg 2-4, A History of Mozambique By M. D. D. Newitt pg 189-191)

The Quirimbas Islands Project (Cabo Delgado, Mozambique): Report of the 2015 Campaign by Jorge de Torres Rodríguez et al. pg 61-62.

The Materiality of Islamisation as Observed in Archaeological Remains in the Mozambique Channel by Anderson, Nathan Joel pg 123-125

Ivory and Slaves in East Central Africa: Changing Pattern of International Trade in East Central Africa to the Later Nineteenth Century by Edward A. Alpers pg 73-74, 94-96, 129, 131-133, 179-180, A History of Mozambique By M. D. D. Newitt pg 192-192)

Origins of the Tungi sultanate (Northern Mozambique) in the light of local traditions’ by Eugeniusz Rzewuski, pg 195, Ivory and Slaves in East Central Africa: Changing Pattern of International Trade in East Central Africa to the Later Nineteenth Century by Edward A. Alpers pg 128-129

Archaeological impact assessment conducted for the proposed Liquefied Natural Gas project in Afunji and Cabo Delgado peninsulas, Palma district By Leonardo Adamowicz pg 15-27, for the revival of the al-shirazi dynasty in 18th century Kilwa, see: A Revised Chronology of the Sultans of Kilwa in the 18th and 19th Centuries by Edward A. Alpers

The Materiality of Islamisation as Observed in Archaeological Remains in the Mozambique Channel by Anderson, Nathan Joel pg 127-132

East Africa and the Indian Ocean by Edward A. Alpers pg 132-138

Archaeological impact assessment conducted for the proposed Liquefied Natural Gas project in Afunji and Cabo Delgado peninsulas, Palma district By Leonardo Adamowicz pg 28-29, 35-38

A History of Mozambique By M. D. D. Newitt pg 54, 64, 72, 75-76, 91, 139-140)

A History of Mozambique By M. D. D. Newitt pg 140-141, 240-241, 268-270, 320

A History of Mozambique By M. D. D. Newitt pg 41, 55, 151-152, 156, 160-166)

A History of Mozambique By M. D. D. Newitt 261-262, 287-289-292, 296-297, 348)

A History of Mozambique By M. D. D. Newitt pg 349-355, for the formal colonization of northern Mozambique and the manuscripts this period generated, see: Swahili manuscripts from northern Mozambique by Chapane Mutiua, pg 43-49

love your content!

Thank you Isaac, love what you do.