A history of Grande Comore (Ngazidja) ca. 700-1900.

State and society on a cosmopolitan island

Situated a few hundred miles off the East African coast are a chain of volcanic islands whose history, society, and urban settlements are strikingly similar to the coastal cities of the mainland.

The Comoro archipelago forms a link between the East African coast to the island of Madagascar like a series of stepping stones on which people, domesticates, and goods travelled across the western Indian Ocean.

The history of Comoros was shaped by the movement and settlement of different groups of people and the exchange of cultures, which created a cosmopolitan society where seemingly contradictory practices like matriliny and Islam co-existed.

While the states that emerged on the three smaller islands of Nzwani, Mwali, and Mayotte controlled most of their territories, the largest island of Ngazidja was home to a dozen states competing for control over the entire island.

This article explores the history of Ngazidja from the late 1st millennium to the 19th century.

Location of Grande Comore on the East African Coast.1

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Early history of Grande Comore from the 7th-14th century.

The Comoro Archipelago was settled in the late 1st millennium by speakers of the Sabaki subgroup of Bantu languages from the East African coast. From these early populations evolved the Comorian languages of Shingazidja, Shimwali, Shindzuani, and Shimaore spoken on the islands of Ngazidja, Mwali, Nzwani, and Mayotte respectively. In the later centuries, different parts of the archipelago would receive smaller groups of immigrants including Austroneasian-speakers and Arabs, as well as a continued influx from the Swahili coast.2

Archeological evidence suggests that Comoros' early settlement period is similar to that found along the East African coast. Small settlements of wattle and daub houses were built by farming and fishing communities that were marginally engaged in regional trade but showed no signs of social hierarchies. At Ngazidja, the 9th-12th century settlement at Mbachilé had few imported ceramics (about 6%), while another old village contained an Islamic burial but little evidence of external contact.3

The ruins of later settlements on Ngazidja in the 13th-14th century include traces of masonry buildings of coral lime and more imported pottery, especially in the town of Mazwini. According to local tradition, this early settlement at Mazwini was abandoned and its inhabitants founded the city of Moroni. It was during this period that the Comoros islands first appeared in textural accounts often associated with the Swahili coast. The earliest of these accounts may have been al-idrisis’ probable reference to Nzwani (Anjouan), but the more certain reference comes from the 15th-century navigator Ibn Majid who mentions Ngazidja by its Swahili name.4

Moroni, early 20th century.

The emergence of states on Grande Comore (15th-17th century)

The Comoro Islands were part of the 'Swahili world' of the East African coastal cities and their ruling families were often related both agnatically and affinally. Beginning in the 13th century, the southernmost section of the Swahili coast was dominated by the city of Kilwa, whose chronicle mentions early ties between its dynasty and the rulers of Nzwani. By the 15th century, the route linking Kilwa to Comoros and Madagascar was well established, and the cities lying along this route would serve as a refuge for the Kilwa elite who fled the city after it was sacked by the Portuguese armies of Francisco de Almeida and his successors. It was during this period between the 15th and 16th centuries that the oldest states on Ngazidja were founded.5

Traditional histories of Ngazidja associate the oldest dynasties on the Island with the so-called 'Shirazi', a common ethnonym that appears in the early history of the Swahili coast —In which a handful of brothers from Shiraz sailed to the east African coast, married into local elite families, and their unions produced the first rulers of the Swahili cities—. Ngazidja’s oral tradition is both dependent upon and radically different from Swahili tradition, reflecting claims to a shared heritage with the Swahili that were adapted to Ngazidja’s social context.6

Ngazidja’s Shirazi tradition focuses on the states that emerged at Itsandra and Bambao on the western half of the island. In the latter, a ‘Shirazi’ princess from the Swahili coast arrived on the island and was married to Ngoma Mrahafu, the pre-existing ruler (bedja) of the land/state (Ntsi) of southern Bambao, the daughter born to these parents was then married to Fe pirusa, ruler of northern Bambao. These in turn produced a son, Mwasi Pirusa, who inherited all of Bambao. A later shipwreck brought more 'Shirazis' from the Swahili city of Kilwa, whose princesses were married to Maharazi, the ruler of a small town called Hamanvu. This union produced a daughter who was then married to the ruler of Mbadani, and their daughter married the ruler of Itsandra, later producing a son, Djumwamba Pirusa, who inherited the united state of Itsandra, Mbadani and Hamanvu.7

This founding myth doubtlessly compresses a long and complex series of interrelationships between the various dynastic houses in Comoros and the Swahili coast. It demonstrates the contradictions inherent in establishing prestigious origins for local lineages that were culturally matrilineal; where the sons of a male founder would have belonged to the mother's lineage and undermined the whole legitimation project. Instead of Shirazi princes as was the case for the Swahili, the Ngazidja traditions claim that it was Shirazi princesses who were married off to local rulers (mabedja), and were then succeeded by the product of these unions, whether sons or daughters, that would take on the title of sultan ( mfaume/mflame).8

These traditions also reflect the genetic mosaic of Comoros, as recent studies of the genetic heritage of modern Comorians show contributions predominantly from Africa, (85% mtDNA, 60% Y-DNA) with lesser amounts from the Middle East and South-East Asia.9 But as is the case with the Swahili coast, the process of integrating new arrivals from East Africa and the rest of the Indian Ocean world into Comorian society was invariably complex, with different groups arriving at different periods and accorded different levels of social importance.

Ruins of an old mosque on Grande Comore, 1884, ANOM

‘miracle mosque’ north of Mitsamiouli, Grande Comore

Traditional accounts of Comorian history, both written and oral, stress the near-constant rivalry between the different states on Ngazidja, as well as the existence of powerful rulers in the island's interior. Portuguese accounts from the early 16th-century note that there were around twenty independent states on Ngazidja, they also remark on the island’s agricultural exports to the Swahili coast, which included "millet, cows, goats, and hens" that supply Kilwa and Mombasa.10

The Comoro ports became an important stopping point for European ships that needed provisions for their crew, and their regular visits had a considerable political and economic impact on the islands, especially Nzwani. While the islands didn't fall under Portuguese control like their Swahili peers, several Portuguese traders lived on the island, carrying on a considerable trade in livestock and grain, as well as Malagasy captives. By the middle of the 16th century, Ngazidja was said to be ruled by Muslim dynasties "from Malindi"11 —a catchall term for the Swahili coast.

Later arrivals by other European ships at the turn of the 17th century had mixed encounters with the rulers of Ngazidja. In 1591 an English crew was killed in battle after a dispute, another English ship in 1608 was warmly received at Iconi, while a Portuguese crew in 1616 reported that many of their peers were killed. Ngazidja's ambiguous reputation, and its lack of natural harbors, eventually prompted European ships to frequent the island of Nzwani instead.12 However, the pre-existing regional trade with the Swahili coast, Madagascar and Arabia continued to flourish.

The island of Anjouan (Nzwani)

State and society on Grande Comore: 17th-19th century.

By the 17th century, the sultanates of Ngazidja had been firmly established, with eleven separate states, the most powerful of which were Itsandra and Bambao. Each sultanate was centered around a political capital, which generally included a palace where the sultan (Mfaume wa Nsti) resided next to his councilors. Sometimes, a powerful sultan would succeed in imposing his hegemony over all the sultanates of the island and thus gain the title of Sultan Ntinbe. Power was organized according to a complex hierarchy that extended from the city to the village, with each local leader (mfaume wa mdji) providing its armies, raising taxes, and settling disputes, while religious scholars carried out social functions and also advised the various rulers.13

The choice of the sultan was elective, with candidates being drawn from the ruling matrilineage. The sultan was assisted by a council comprised of heads of lineages and other patricians, which restricted his powers through assemblies. The various local sultans nominally recognized the authority of the sultan ntibe, an honorific office that was alternatively claimed by the two great clans; the Hinya Fwambaya of Itsandra (allied with Washili and Hamahame), and the Hinya Matswa Pirusa, of Bambao (allied with Mitsamiouli, Hambou, Boudé and Boinkou).14 while other clans included the M'Dombozi of Badgini (allied with Domba and Dimani)

the states (Ntsi) of Grande Comore in the late 19th century15

Kavhiridjewo palace ruins in Iconi, dated to the 16th-17th century16

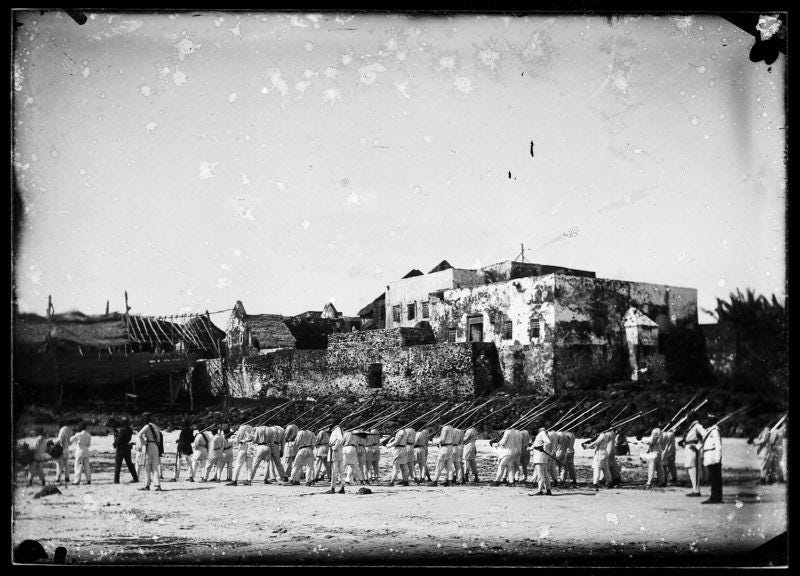

Sultan Ali’s army parading in front of the great mosque of Moroni, ca. 1884, MNHN

The second half of the 17th century was a period of prosperity for Ngazidja, particularly the state of Itsandra, which, under the rule of Sultan Mahame Said and his successor Fumu Mvundzambanga, saw the construction of the Friday mosques in Itsandramdjini and Ntsudjini. Sultan Fumu was succeeded by his niece, Queen Wabedja (ca. 1700-1743) who is particularly remembered in local traditions for her lengthy rule both as regent for her three short-lived sons and as a Queen regnant for nearly half a century.17

A skillful diplomat, Queen Wabedja married off her daughters to the ruling families of the rival clan of Hinya Matswa Pirusa, which controlled the cities of Mitsamihuli, Ikoni, and Moroni. Trade with the Swahili coast boomed with Itsandramdjini as the island’s premier commercial centre. Itsandra became a center of learning whose scholars included Princess Mmadjamu, a celebrated poet and expert in theology and law.18

The period of Wabedja's rule in the early 18th century is remembered as a golden age of Ngazidja's history. Like most of the Swahili coast, the island of Ndazidja received several Hadrami-Alwai families in the 18th century, originally from the Swahili city of Pate (in Kenya’s Lamu archipelago). They married locally and were acculturated into the dominant Comorian culture, particularly its matriclans. These families reinvigorated the society's Islamic culture and learning, mostly based in their village in Tsujini, but also in the city of Iconi. However, unlike the Swahili dynasties and the rulers of Nzwani, the Alawi of Ngazidja never attained political power but were only part of the Ulama.19

Most cities (mdji) and towns in Ngazidja are structured around a public square: a bangwe, with monumental gates (mnara) and benches (upando) where customary activities take place and public meetings are held. The palaces, mosques, houses, and tombs were built around these, all enclosed within a series of fortifications that consisted of ramparts (ngome), towers (bunarisi), and doors (goba).20

In Ngazidja, each city is made up of matrilineages ordered according to a principle of precedence called kazi or mila21. The Comorian marital home belongs to the wife, but the husband who enters it becomes its master. It is on this initial tension that broader gender relationships are built, and the house's gendered spaces are constructed to reflect Comorian cultural norms of matrilocality. Larger houses include several rooms serving different functions, with some that include the typical zidaka wall niches of Swahili architecture and other decorative elements, all covered by a mix of flat roofs and double-pitched thatched roofs with open gables to allow ventilation.22

Bangwe of Mitsudje, and Funi Aziri Bangwe of Iconi

View of Moroni, ca. 1900, ANOM. with the bangwe in the middle ground

Mitsamiouli street scene, early 20th century

At the end of her reign, Wabedja handed over power to her grandson Fumnau (r. 1743-1800), a decision that was opposed by Nema Feda, the queen of the north-eastern state of Hamahame. Nema Feda marched her army south against Fumnau’s capital Ntsudjini, but was defeated by the combined forces of Bambao and Itsandra. The old alliance between the two great clans crumbled further over the succession to the throne of Washili. This conflict led to an outbreak of war in which the armies of Itsandra's king Fumnau and Bambao's king Mlanau seized control over most of the island's major centers before Fumnau turned against Mlanau's successor and remained sole ruler of Ngazidja with the title of sultan ntibe.23

During this period, naval attacks from northern Madagascar beginning in 1798 wreaked havoc on Ngazidja, prompting sultan Fumnau to construct the fortifications of Itsandramdjini, a move which was copied by other cities.24 The island remained an important center of trade on the East African coast. According to a visitor in 1819, who observed that the Ngazidja had more trade than the other islands, exporting coconuts to Zanzibar, cowries to India, and grain to Nzwani.25

West rampart, Ntsaweni, Grande Comore

Northern rampant of Fumbuni, Grande Comore

Gerezani Citadel, Itsandra, Grande Comore

Grande Comore in the 19th century

The sultans of Ngazidja maintained close ties with Nzwani and Zanzibar, and the island's ulama was respected along the Swahili coast. While both Nzwani and Zanzibar at times claimed suzerainty over the island, neither was recognized by any of Ngazidja's sultans. The island's political fragmentation rendered it impossible for Nzwani's rulers to claim control despite being related to some of the ruling families, while Zanzibar's Omani sultans followed a different sect of Islam that rendered even nominal allegiance untenable.26

The 19th century in Ngazidja was a period of civil conflict instigated in large part by the long reign of the Bambao sultan Ahmed (r. 1813-1875), and his ruinous war against the sultans of Itsandra. In the ensuing decades, shifting political alliances and wars between all the major states on the island also came to involve external powers such as the Portuguese, French, and Zanzibar (under the British) whose military support was courted by the different factions.

In the major wars of the mid-19th century, sultan Ahmed defeated sultan Fumbavu of Itsandra, before he was deposed by his court in Bambao for allying with Fumbavu's successor Msafumu. Ahmed rallied his allies and with French support, regained his throne, but was later deposed by Msafumu. The throne of Bambao was taken by Ahmed's grandson Said Ali who rallied his allies and the French, to defeat Msafumu's coalition that was supported by Zanzibar. Said Ali took on the title of sultan ntibe, but like his predecessors, had little authority over the other sultans. This compelled him to expand his alliance with the French by inviting the colonial company of the french botanist Leon Humblot, to whom he leased much of the island (that he didn't control).27

In January 1886, against all the traditions of the established political system, Said Ali signed a treaty with France that recognized him as sultan of the entire island and established a French protectorate over Ngazidja. This deeply unpopular treaty was met with stiff opposition from the rest of the island, forcing Said Ali to flee in 1890 and the French to bring in troops to depose the Sultans. By 1892, the island was fully under French control and the sultanate was later abolished in 1904, marking the end of its autonomy.28

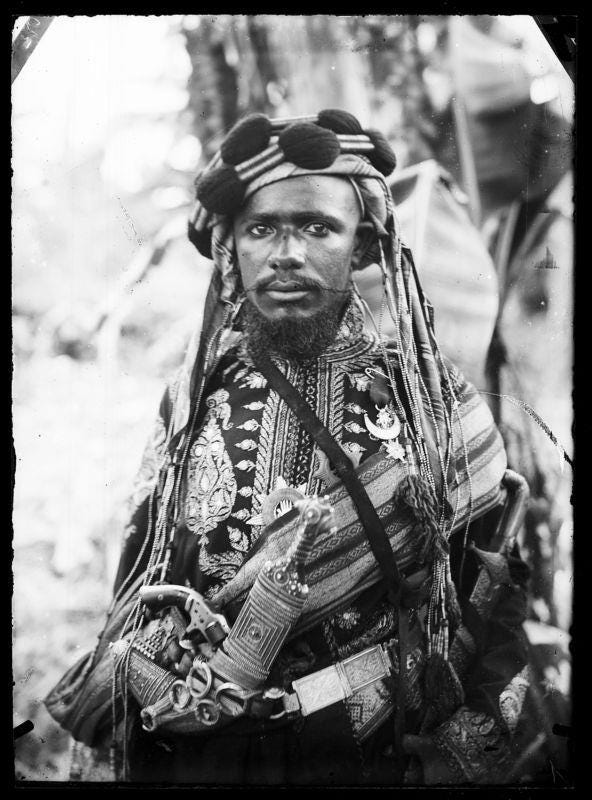

Potrait of Saïd Ali, the last sultan of Grande Comore, ca. 1884, MNHN

Moroni beachfront

The Portuguese invader of Kilwa, Francisco de Almeida, met his death at the hands of the Khoi-San of South Africa,

Read more about the history of one of Africa’s oldest communities here:

Map by Stephanie Wynne-Jones and Ian Walker

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria Jean LaViolette pg 267-268, Islands in a Cosmopolitan Sea: A History of the Comoros By Iain Walker pg 36)

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria Jean LaViolette pg 271, 273-274

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria Jean LaViolette pg 281-282, The Comoro Islands in Indian Ocean Trade before the 19th Century by Malyn Newitt pg 144)

The Comoro Islands in Indian Ocean Trade before the 19th Century by Malyn Newitt pg 142-144)

The Comoro Islands: Struggle Against Dependency in the Indian Ocean by M. D. D. Newitt pg 16, The Making of the Swahili: A View from the Southern End of the East African Coast by Gill Shepherd pg 140

Becoming the Other, Being Oneself: Constructing Identities in a Connected World By Iain Walker pg 60-61, Cités, citoyenneté et territorialité dans l’île de Ngazidja by Sophie Blanchy

Becoming the Other, Being Oneself: Constructing Identities in a Connected World By Iain Walker pg pg 59-64)

Genetic diversity on the Comoros Islands shows early seafaring as a major determinant of human bicultural evolution in the Western Indian Ocean by Said Msaidie

The Comoro Islands: Struggle Against Dependency in the Indian Ocean by M. D. D. Newitt pg 16)

The Comoro Islands: Struggle Against Dependency in the Indian Ocean by M. D. D. Newitt pg 146-151, Islands in a Cosmopolitan Sea: A History of the Comoros By Iain Walker pg 53)

Islands in a Cosmopolitan Sea: A History of the Comoros By Iain Walker pg 54-55)

Cités, citoyenneté et territorialité dans l’île de Ngazidja by Sophie Blanchy

Islands in a Cosmopolitan Sea: A History of the Comoros By Iain Walker pg 68, 44)

Map by Charles Viaut et al, these states constantly fluctuated in number from anywhere between 8 to 12

This and similar photos by Charles Viaut et al

Islands in a Cosmopolitan Sea: A History of the Comoros By Iain Walker pg 71)

Islands in a Cosmopolitan Sea: A History of the Comoros By Iain Walker pg 71)

Sufis and Scholars of the Sea: Family Networks in East Africa, 1860-1925 by Anne K. Bang pg 27-31, 47-53)

Le patrimoine bâti d’époque classique de Ngazidja (Grande Comore, Union des Comores). Rapport de synthèse de prospection et d’étude de bâti by Charles Viaut et al., pg 40-41)

Cités, citoyenneté et territorialité dans l’île de Ngazidja by Sophie Blanchy

La maison urbaine, cadre de production du statut et du genre à Anjouan (Comores), XVIIe-XIXe siècles by Sophie Blanchy

Islands in a Cosmopolitan Sea: A History of the Comoros By Iain Walker pg 72-73)

The Comoro Islands: Struggle Against Dependency in the Indian Ocean by M. D. D. Newitt pg 22)

Islands in a Cosmopolitan Sea: A History of the Comoros By Iain Walker pg 73, 102)

Islands in a Cosmopolitan Sea: A History of the Comoros By Iain Walker pg 102)

Islands in a Cosmopolitan Sea: A History of the Comoros By Iain Walker pg 103-104, The Comoro Islands: Struggle Against Dependency in the Indian Ocean by M. D. D. Newitt pg 32)

Comoro Islands: Struggle Against Dependency in the Indian Ocean by M. D. D. Newitt pg 32)