A Pictorial History of Africa: Insights from Ancient Figurative Art.

While travelling through West Africa between 1908 and 1910, the German ethnographer Leo Frobenius visited the city of Ife (in S.W Nigeria), where he had heard accounts of a remarkable statue of the sea deity Olokun. During his brief stay, he quickly accumulated an impressive collection of figurative artworks, the most spectacular of which was a bronze head representing Olokun:

“Before us stood a head of marvellous beauty, wonderfully cast in antique bronze, true to life, encrusted with a patina of glorious dark green… very finely chased, indeed like the finest Roman examples.

It cannot be said to be “negro” in countenance, although it is covered with quite fine tattooed lines, which at once contradicts any suggestion of its having been brought from abroad’’1

Copper-alloy head. 14th-15th century. Ife, Nigeria. British Museum.

Eager to draw attention to his discoveries, Leo Frobenius interpreted the artworks as evidence of an outpost of classical antiquity connected to the mythical “empire” of Atlantis. This interpretation was widely publicised: in January 1911, the New York Times reported that Frobenius “has discovered indisputable proof of the existence of Plato’s legendary continent of Atlantis.”2

Frobenius’s own account of the artworks combines idiosyncratic theories proposing diffusionist origins for the city’s impluvium courtyard architecture from Roman North Africa, sensationalist claims describing Yoruba culture as a “crystallization of Western civilization in its Euro-African form,” and, at the same time, an acknowledgment that the artworks of Ife constituted “a form of local art.”3

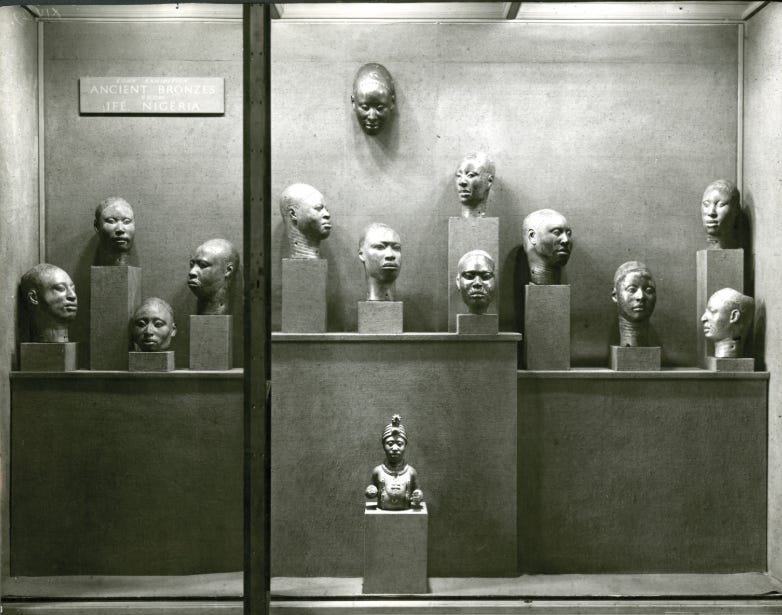

Twelve heads from Ife’s Wúnmọníjẹ̀ Compound on display at an exhibition held at the British Museum in 1947–48. Image by T. L. Evans

In the century since Frobenius’s writings, subsequent archaeological research has discarded much of the exoticism once associated with the art of Ife. Discoveries of more copper-alloy castings and other material evidence have made it possible to reconstruct the city’s historical development with greater accuracy.

Thanks to its vast corpus of figurative art, the medieval city of Ife, which scarcely appears in contemporary written sources, is revealed to have been the political and cultural capital of a vast kingdom.

Its regional influence in the construction of potsherd pavements, impluvium courtyard houses, and the (independent) invention of glass has overturned diffusionist theories concerning the emergence of social complexity in pre-colonial Africa.4

Terracotta head. Ife, Nigeria. 12th–15th century. private collection, Met Museum

Crowned head. Ife, Nigeria. 12th–15th century. National Commission for Museums and Monuments, Nigeria

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

About 90% of Sub-Saharan Africa’s material cultural legacy is kept in Western museums and private collections outside of the continent.

A substantial portion of this material consists of collections of figurative artworks from societies such as the Sapi and the Loango, for which they constitute the principal historical sources, given the scarcity of textual accounts.

In recent years, the proliferation of archeological discoveries and studies of African manuscripts has significantly expanded our understanding of the continent’s history. However, comparatively less attention has been devoted to the rich archive of African artworks, which could complement and deepen our knowledge of historical African societies.

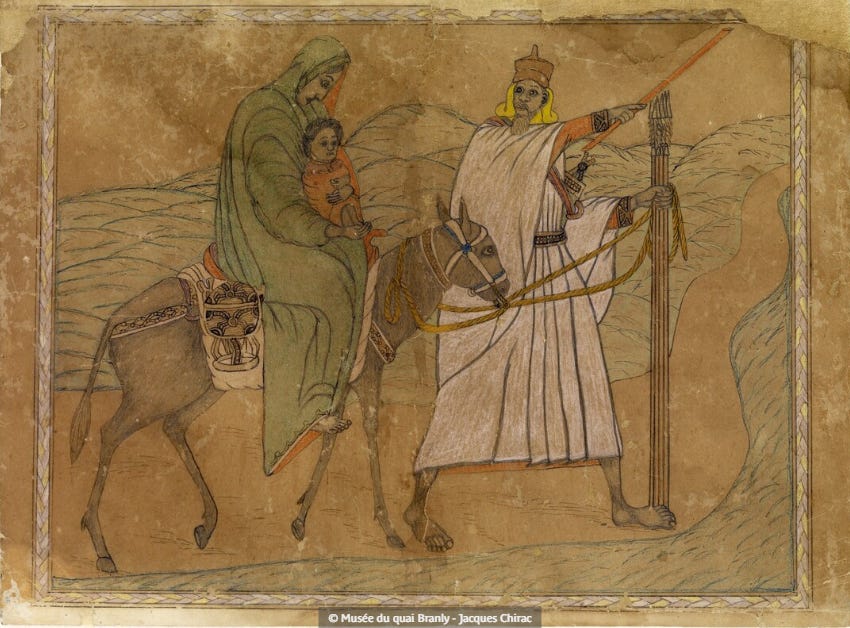

The Flight into Egypt. Bamileke artist. Fumban, Cameroon. Quai Branly

The Sapi, whose communities were distributed along the Atlantic coast of present-day Sierra Leone and Guinea during the 15th and 16th centuries, occupied a unique cultural and geographic position between the Muslim interior of the Mande-speaking kingdoms, the Atlantic world of the Christian Portuguese, and the indigenous societies of the coast.

This “triple heritage” and the complex ways in which the Sapi negotiated these influences are well represented in the figurative art produced by their highly skilled artisans. Their artworks combine motifs derived from local cosmologies with representations of Sapi figures in hybrid attire, often holding objects associated with the Muslim societies of the interior, alongside foreign elements drawn from the Iberian Christian world.

(left) Ivory salt-cellar with lid, decorated with snakes, dogs, and 4 human figures. Sapi artist. Sierra Leone. 15th-16th century. Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin (right) Ivory salt-cellar with lid decorated with a seated female figure, featuring depictions of snakes and dogs. Sapi artist. Sierra Leone. 15th-16th century. Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin.

‘The kiss of Judas’ ivory pyx by Sapi artist, Sierra Leone, ca. 1490-1530. Walters Art Gallery. (see previous essay on Early Christianity in West Africa (ca. 1500-1820) )

In Loango, the devolution of centralized authority to titled officials (mafuks) along the coast of present-day Congo Rep. during the commodities boom of the late 19th century led to a marked expansion in the production of figurative artwork in ivory.

Among the best sculptures from this region are intricately carved ivory tusks depicting scenes of daily life and the social transformations of the period. Narrative themes are arranged in a spiral format, “like the decoration of the column of Trajan,” depicting African and European figures, as well as a range of real and mythical animals, some of whose symbolic meanings have since been lost.

Scenes of daily life carved in ivory. Loango, Gabon. late 19th century. British Museum

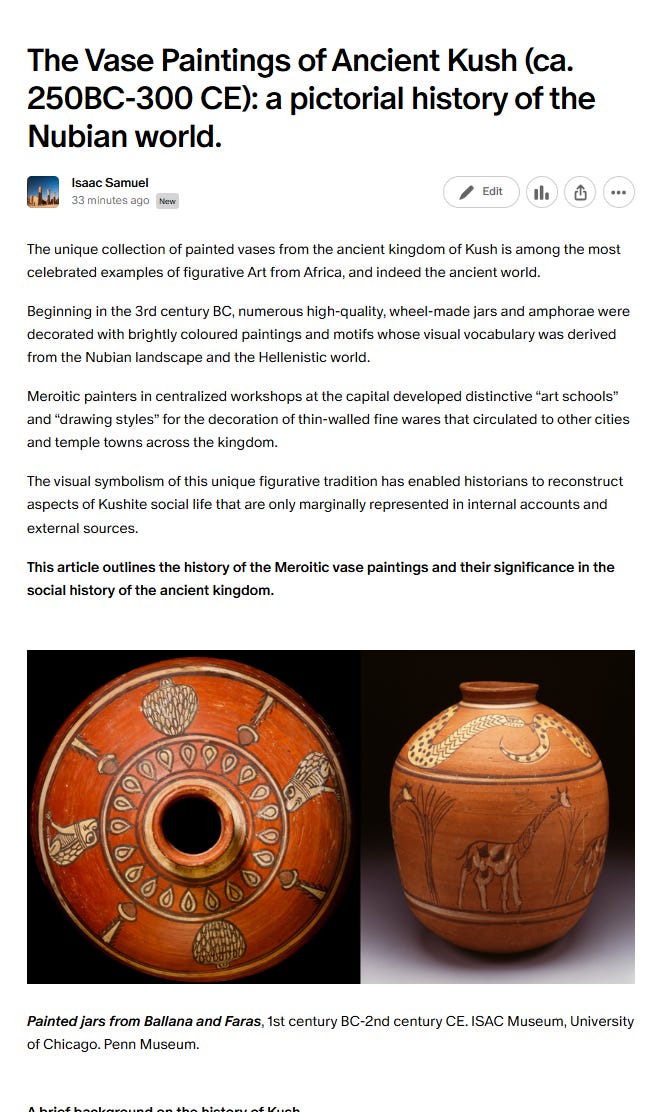

The significance of figurative art as a complement to textual and archaeological research on African history is especially well illustrated by the celebrated corpus of painted vessels from the Kingdom of Kush during the Meroitic period (270 BC-360 CE).

From the 3rd century BC onward, numerous high-quality, wheel-made jars and amphorae were decorated with brightly coloured paintings and motifs whose visual vocabulary was derived from the Nubian landscape and the Hellenistic world.

Meroitic painters in centralized workshops at the capital developed distinctive “art schools” and “drawing styles” for the decoration of thin-walled fine wares that circulated to other cities and temple towns across the kingdom.

The visual symbolism of this unique figurative tradition has enabled historians to reconstruct aspects of Kushite social life that are only marginally represented in internal accounts and external sources.

The vase paintings of ancient Kush are the subject of my Latest Patreon article. Please subscribe to read more about it here:

The Voice of Africa: Being an Account of the Travels of the German Inner African Exploration Expedition in the Years 1910-1912 · Volume 1 By Leo Frobenius pg 98, 310

What Is African Art?: A Short History By Peter Probst, pg 38

The Voice of Africa: Being an Account of the Travels of the German Inner African Exploration Expedition in the Years 1910-1912 · Volume 1 By Leo Frobenius, pg 310-328

An excellent summary of research on Ife: A Copper Alloy Head Count: Contextualising and Accounting for the Wúnmọníjẹ̀ Compound Discoveries of Ilé-Ifẹ̀, Nigeria by Tomos Llywelyn Evans. Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba. Ife History, Power, and Identity, c. 1300, by S. P. Blier. The Yorùbá: A New History by A. Ogundiran.