An island bridge in the Indian Ocean: The history of Mayotte in the French Comoros (ca. 800-1841)

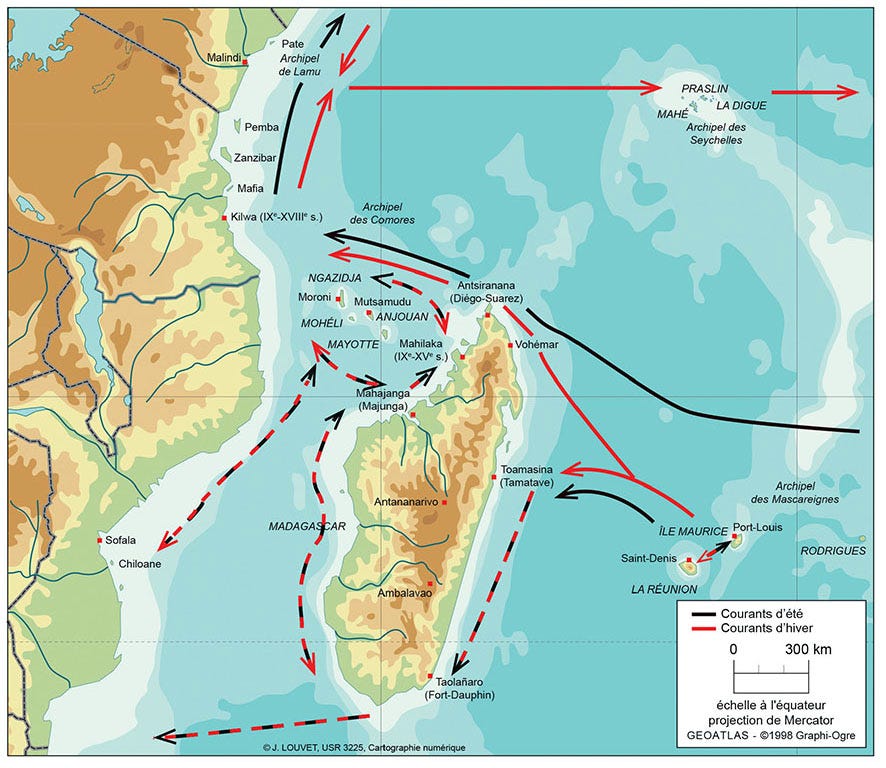

The Comoros archipelago, a natural stopover between the East African coast and Madagascar, was a crossroads for travelers and seafarers from across the African and Asian continents.

At the nexus of this diverse cultural exchange was the island of Mayotte, whose ethnically heterogeneous population attests to its role as an island bridge connecting the two worlds. On Mayotte, settlements of Shimaore speakers (a Bantu language related to Swahili) alternate with those of Kibushi speakers (an Austronesian language that's a dialect of Malagasy).

In the Middle Ages, urbanized communities on Mayotte participated in the maritime trading networks of the Indian Ocean. After the 15th century, the island was unified by an independent sultanate based at Tsingoni. The Sultanate of Mayotte lasted until the French colonial period in 1841, and the island is currently considered a French overseas department.

This article explores the pre-colonial history of the island of Mayotte from the late 1st millennium to the 19th century.

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more on African history and keep this blog free for all:

The early history of Mayotte

The territory of Mayotte, known locally as Maore, consists of a large island (Grande Terre) of 363 km² that is surrounded by about 30 small islands.

The island of Mayotte, like the rest of the Comoro Archipelago, likely served as a route for Holocene hunter-gatherers from Africa who traveled to Madagascar by island hopping from the East African mainland, as evidenced by finds of stone tools and bones with tool marks found at sites in Madagascar dated to 2288–2035 BC and 402–204 BC.1 Direct evidence from the known archaeological sites on Mayotte itself, however, suggests that the human settlement began during the 1st millennium of the common era, with successive waves of migration continuing into the modern period.2

The first permanent settlement on Mayotte emerged at Dembeni, a 5ha site that was occupied from the 9th-11th century by a mixed farming and fishing community that lived in rectilinear daub and wattle houses. The material culture of the site consists mostly of local ‘TIW’ (Triangular incised ware) pottery, which is the material signature of Swahili-speaking groups on the East African coast. There were also imported wares of Abbasid, Persian, and Chinese origin, as well as chlorite schist vases from Madagascar and glassware from Egypt.3

Unlike some of the early Swahili sites, the island of Mayotte doesn't appear in external accounts before the late 15th century.4 This is despite the relatively high proportion of imported wares that would suggest the presence of seafarers from beyond the East African coast. Other archaeological finds of shell-impressed vessels and chlorite schist vases indicate that the inhabitants of Dembeni were in contact with communities in Madagascar. It has thus been argued that speakers of Austroneanian languages to which the Ki-bushi language belongs, were also present on the island during the Dembeni phase.5

During the Dembeni period, the Comoros archipelago served as a warehouse for Malagasy products, especially rock crystal, which was described in external Arab accounts as one of the products exported from the ‘Zanj coast’ in the 11th century to be reworked in Fatimid Egypt. The abundance of this material at Dembeni compared to other East African coastal sites indicates that Mayotte was a major transshipment point in the trade circuits of the western Indian Ocean.6

The Dembeni phase on Mayotte lasted until the 11th/13th century, with two main sites; Dembeni and Bagamoyo, the latter of which is a necropolis dating from the 9th century. This early phase was succeeded by several archaeological sites that are periodized based on the type of local pottery traditions. These sites, which flourished during the late Middle Ages, belong to the Hanyoundrou tradition (11th-13th century); the Acoua tradition (14th century), and the Chingoni tradition (15th century).7

Sailboats near Mayotte, ca. 1924. BNF, Paris.

The necropolis of Bagamoyo on Petite Terre, Mayotte. image by M. Pauly

Islands and archipelagos of the western Indian Ocean showing the main ocean currents. Map by Laurent Berger and Sophie Blanchy8

During the late Middle Ages, increased agricultural development resulted in the establishment of large settlements (villages and towns). Most of the structures at these sites were built with daub and wattle, save for elite residencies, a few mosques, and ramparts that were constructed with coral and basalt blocks.

Important settlements from this period include; the site of Acoua whose ruins include a stone wall enclosing an area of 4ha dated to the 11th century, a 12th century mosque and several domestic structures; Mbwanatsa, a 13th century site with a ruined rampart and a mosque; Kangani, an 11th century site with ruins of stone houses; Mitseni, an 11th-15th century site with ruins of a rampart, three mosques and tombs; and Tsingoni, the later capital of the Mayotte Sultanate in the 16th -18th centuries.9

Excavations at the sites of Bagamoyo (9th-15th century) and Antsiraka Boira (12th century) uncovered Muslim burials, pointing to Mayotte's links with the wider Muslim world. Material culture from the site of Acoua (11th-15th century) included pottery similar to the Swahili wares found at Kilwa, indicating an influx of populations from the latter, especially in the 14th-15th century. The site also contained imported Chinese and Yemeni pottery, and Indian glass beads, providing further evidence of Mayotte's integration into the trading networks of the Indian Ocean world.10

Ruins of Mitseni, Mayotte. images by M. Pauly

The Polé mosque on Petite-Terre, Mayotte. images by M. Pauly

State and society on Mayotte during the late Middle Ages

From the 11th to the 15th centuries, political power in Mayotte was fragmented into independent chiefdoms that local chronicles attribute to the Fani, a title for local rulers. The Fani first appeared in written documents in the 1614 account of English captain Walter Peyton, who mentions that the father of the king of the island was called Fani Moheli. A few years earlier, in 1611, another account noted that this king was called Sariffo booboocarree [Sharifu Aboubacari], indicating links to the Sharifian groups of the Hejaz.11

Traditional King-lists, oral accounts, and later chronicles for this period refer to a complex history of dynastic intermarriages between local elite families and immigrant families from the Swahili coast who called themselves shirazis. There were also intermarriages with the Sakalava of Madagascar and Sharifian families from Pate/Yemen. Given the matrilineal character of Comorian society, historical traditions regarding these elite intermarriages contain references to women as founders of important lineages, and at times mention intermarriages with foreign princesses —instead of princes— since power was often transmitted through the female line.12

The Oral accounts indicate that the Fani dynasty ended with the establishment of the Shirazi dynasty in the late 15th century at the height of the Kilwa sultanate. Historians suggest that these shirazi traditions were a result of the migration of elite families from Kilwa to the Comoros archipelago in the 15th century13 (where they are attested at Ngazidja and Nzwani) and the southern Swahili coast at Tungi in Mozambique. In Comoros, the shirazi dynasty's founder, Hassan, is said to have lived in Nzwani from where he sent his son Mohammed to Mayotte, where the latter married the daughter of the fani of Mtsamboro.14

Mohammed's son Issa then claimed the title of sultan of Mayotte—through his mother’s lineage, and moved to Tsingoni where he built a mosque that bears an inscription with his name and is dated 994 AH (1538 CE). Recent excavations in and around the mosque show that it was preceded by a smaller mosque constructed in the 13th-14th century during the time of the Fani rulers.15

Between the 15th and 16th centuries, centralized political institutions emerged on the island, with kings called wafaume (Swahili word for king), who unified earlier chiefdoms within the context of growing social hierarchization. In Mayotte's hierarchical society, the aristocracy resided in urban areas like Tsingoni and Mtsamboro which were characterized by coral-stone mosques and palaces, while the countryside was populated by free peasants and slaves living in small hamlets.16

3D photogrammetric survey of the Tsingoni mosque and the surveys. image by A. Daussy, Inrap

Tsingoni mosque and mihrab inscription. images by M. Pauly

Old tombs of Tsingoni, Mayotte. ca. 1973, Quai Branly.

Mayotte as a trade hub during the 16th and 17th centuries.

The European irruption on the East African coast during the 16th century wasn’t felt on Mayotte, as the islands remained on the periphery of the Portuguese maritime empire that subsumed parts of the Swahili coast.

Around 1506, a Portuguese captain at Kilwa mentioned the island of ‘Maotoe’ (Mayotte) among the six islands in the Comoro archipelago whose Muslim rulers supplied the Swahili cities of Kilwa and Mombasa with “cattle, great mil (sorghum), rice, ginger, fruit, and sugar”. By the mid-16th century, the Portuguese captain Balthazar Lobo de Sousa mentioned that Mayotte was ruled by a single king and had “30 ‘cities’ of 300 to 400 inhabitants,” suggesting that the island’s population exceeded 10,000.17

According to the account of the Turkish admiral Piri Re’is, written in 1521-1526, Portuguese ships attacked the capital Tsingoni in the early 16th century but the fleet had been wrecked on the surrounding reefs and the crew was marooned on the island. He mentions that the island was ruled by a sultan/king (unlike Mwali and Ngazidja which were ruled by sheikhs) The sultan of Mayotte ruled from Chin Kuni (Tsingoni) over a population that was ‘black and white’ comprised of Shafi'i Muslims: “Among them there is no hypocrisy.”18

Mayotte and the Comoros archipelago remained important stopovers on maritime trade routes, carrying gold, ivory, iron, and captives, as well as supplying provisions for European ships.

In 1620 the French trader Beaulieu met two ships off Ngazidja coming from Mayotte and heading for Lamu, their port of registry: they were loaded with a great quantity of rice, smoked meat, and “many slaves.” The captives exported from Mayotte and the Comoros archipelago were most likely purchased from Madagascar, where ‘Buki’ (Malagasy) slaves appear in multiple accounts from the 16th-17th century.19

Piri Re’is early 16th-century description of the islands as ‘warehouses’ for these captives suggests that the trade had a demographic effect on the islands.20 The name ‘Ki-Bushi’ for the Malagasy dialect of Mayotte is itself an exonymous term derived from the Comorian word for Malagasy people as ‘Bushi’ similar to the Swahili’s ‘Buki’.21

In the first half of the 17th century, prior to their establishment of the Cape colony in 1652, the Dutch briefly used the island of Mayotte as a supply point, much like Nzwani was to the English, albeit to a lesser extent.

In 1601 a Dutch fleet purchased a wide range of provisions, reporting that there were large numbers of cattle and fruit; in 1607 another Dutch ship was able to take on board 366 head of cattle, 276 goats, and ‘an extraordinary quantity of fruit’. In 1613, a Dutch fleet stayed five weeks at Mayotte while mustering strength to attack the Portuguese on Mozambique island. And in I6I5 Mayotte was still the island most frequented by the Dutch in the Comoros. However, the reefs that provided shelter in the lagoon were ultimately too great a hazard forcing the Dutch to abandon the island in favour of the Cape.22

Outrigger canoe, Basalt rocks, and stone houses. ca. 1955. Mayotte or Ngazidja, Quai Branly.

Mayotte’s politics from the period of Inter-Island warfare to the early colonial era (1700-1841)

The rulers of Mayotte were kin to the rulers of Nzwani who claimed seniority and thus suzerainty over Mayotte and the neighboring island of Mwali. However, these links weakened with time as the two islands descended into a protracted period of dynastic rivalry and inter-island war as early as 1614. Tradition attributes this hostility to dynastic factors primarily concerned with the legitimacy of, and hierarchy among, the ruling lineages. These internal processes were exacerbated by the demand for provisions for European ships and the supply of mercenaries from the latter.23

After a lull in hostilities, succession crises in Mayotte resulted in Nzwani reportedly establishing its suzerainty over Mayotte in the mid-18th century, but in 1781 Mayotte's king refused to pay tribute to Nzwani. The ruler of Nzwani thus invaded Mayotte forcing the latter to pay the tribute, after which Nzwani’s forces withdrew from the island, taking some as captives. In 1791, the ruler of Nzwani invaded Mayotte again with a fleet of 35 boats accompanied by 300 French mercenaries, presumably to obtain tribute and slaves, but the Nzwani army was defeated and the island reverted to the local authority.24

In the last decade of the 18th century, succession struggles in Nzwani resulted in one of the claimants allying with the Sakalava of Madagascar who were then employed as mercenaries against his rival and neighboring rulers including Mayotte. The capital Tsingoni and the town of Mtsamboro were sacked and the island's population collapsed during the Sakalava invasion of the East African coast that lasted until 1817. The ruling dynasty of Mayotte was forced to move to the small island at Dzaoudzi from where they forged alliances with the Sakalava kingdom of Boina.25

View of Dzaoudzi, Mayotte. ca. 1845, by M. Varney and A. Roussi.

In 1826, the Sakalava prince Andriantsoli fled from Madagascar to Mayotte, after his kingdom was conquered by the Merina king Radama I. After the latter's death, Andriantsoli returned to reclaim the throne of Boina but was overthrown in a succession conflict, forcing him to flee to Mayotte again in 1832. However, unlike his first exile, the Sakalava prince was not generously received by its ruler Bwana Combo, who attempted to expel the large group of Malagasy that had arrived with him.26

After a series of wars and shifting alliances involving the three islands of Mayotte, Nzwani, and Mwali, the ruling dynasty of Mayotte briefly ceded the island to the ruler Nzwani, Abdallah II in 1835. Bwana Combo remained the ruler of Mayotte while Andriantsoli became the governor. Bwana Combo then joined forces with Abdallah II to invade the island of Mwali, but their forces were shipwrecked and the two were executed by the ruler of Mwali.27

Andriantsoli thus became the sultan of Mayotte but was considered an unpopular ruler. Therefore in 1841, well aware that his hold over the island was tenuous, Andriantsoli ceded sovereignty of Mayotte to France but the latter were fiercely resisted by many Maorians in a series of colonial rebellions in 1849, 1854, and 1856. After pacifying the islanders, the French began importing enslaved and forced labor from the East African coast to the island for their sugar plantations. However, the island remained neglected and under-administered, a situation which prevails to the present day.28

The depopulation of the late 18th century and the import of plantation labor in the colonial period had a significant demographic effect on the island. In 1851, just 17% of the population were native Maorians while 23% were from the rest of Comoros; 26% were Malagasy; and 32% were from Mozambique. By 1866 however, nearly 40% of the population were Maorians, many of whom had doubtlessly been acculturated into the local society through intermarriage. The great majority of Maorais today are thus descended from immigrants who arrived on the island in the 19th century.29

These processes of acculturation and migration would continue to figure prominently in the political and social identity of Mayotte during the colonial period and would play a significant role in the controversial referenda of 1974 and 1976 when the islanders chose to remain a French overseas territory.

Dhow off the coast of Dzaoudzi, Mayotte. ca. 1955. Quai Branly.

Like the Seafarers of the Swahili coast, societies in the interior regions of East Africa traveled across the Great Lakes and established lake ports whose significance to regional trade would be retained well into the modern era.

The history of Navigation on the African Great Lakes is the subject of my latest Patreon article,

Please subscribe to read more about it here:

Maorian women at the maulida shengy festival, ca. 1985. image by J.S. Solway.

Stone tools and foraging in northern Madagascar challenge Holocene extinction models by Robert E. Dewar, Chantal Radimilahy, Henry T. Wright

The Swahili World edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria LaViolette pg 268-271

Early Seafarers of the Comoro Islands: the Dembeni Phase of the IXth-Xth Centuries AD by Henry T. Wright et al. Dembéni, Mayotte (976) Archéologie swahilie dans un département français by Stéphane Pradines

Acoua, archéologie d’une communauté villageoise de Mayotte (archipel des Comores) by Martial Pauly pg 23

Early Seafarers of the Comoro Islands: the Dembeni Phase of the IXth-Xth Centuries AD by Henry T. Wright et al. pg 55-57, Dembéni (Mayotte) – rapport de mission archéologique 1999 by Bruno Desachy et al. pg 14-17, Acoua, archéologie d’une communauté villageoise de Mayotte (archipel des Comores) by Martial Pauly pg 26-30, 74-79.

Acoua, archéologie d’une communauté villageoise de Mayotte (archipel des Comores) by Martial Pauly pg 115-116

Développement de l'architecture domestique en pierre à Mayotte (XIIIe-XVIIe siècle), by Martial Pauly pg 8-20, Société et culture à Mayotte aux XIe-XVe siècles: la période des chefferies by Martial Pauly pg 90-91

La fabrique des mondes insulaires Altérités, inégalités et mobilités au sud-ouest de l’océan Indien by Laurent Berger et Sophie Blanchy

Société et culture à Mayotte aux XIe-XVe siècles: la période des chefferies by Martial Pauly pg 92-97

La diffusion de l’islam à Mayotte à l’époque médiévale by Martial Pauly pg 70-86, Acoua-Agnala M'kiri, Mayotte (976), archéologie d'une localité médiévale (XIe-XVe siècles), entre Afrique et Madagascar by Martial Pauly pg 73-88

Société et culture à Mayotte aux XIe-XVe siècles: la période des chefferies by Martial Pauly pg 69-83, 104-108)

Société et culture à Mayotte aux XIe-XVe siècles: la période des chefferies by Martial Pauly pg 84-85, Islands in a Cosmopolitan Sea: A History of the Comoros By Iain Bruce Walker pg 39, On sharifian families: Les cités - Etats swahili de l'archipel de Lamu , 1585- 1810 by T. Vernet pg 179-180

Acoua, archéologie d’une communauté villageoise de Mayotte (archipel des Comores) by Martial Pauly pg 121-123

Dembéni, Mayotte (976) Archéologie swahilie dans un département français by Stéphane Pradines pg 69-70, Société et culture à Mayotte aux XIe-XVe siècles: la période des chefferies by Martial Pauly pg 85-88

La mosquée de Tsingoni (Mayotte) Premières investigations archéologiques by Anne Jégouzo

Société et culture à Mayotte aux XIe-XVe siècles: la période des chefferies by Martial Pauly pg 104-105

Worlds of the Indian Ocean Vol. 2 by Philippe Beaujard pg 553-554, Islands in a Cosmopolitan Sea: A History of the Comoros By Iain Bruce Walker pg 52-53

L’archipel des Comores et son histoire ancienne. by Claude Allibert prg 34

Slave Trade and Slavery on the Swahili Coast, 1500–1750 by Thomas Vernet pg 44. The Worlds of the Indian Ocean Vol. 2 by Philippe Beaujard pg 560-561,615,

Société et culture à Mayotte aux XIe-XVe siècles: la période des chefferies by Martial Pauly pg 85

L’archipel des Comores et son histoire ancienne. by Claude Allibert prg 20,

The Comoro Islands in Indian Ocean Trade before the 19th century by M. Newitt pg 151-152, Islands in a Cosmopolitan Sea: A History of the Comoros By Iain Bruce Walker pg 70

The Comoro Islands in Indian Ocean Trade before the 19th century by M. Newitt pg 156-157

Islands in a Cosmopolitan Sea: A History of the Comoros By Iain Bruce Walker pg 70-71, also read a summary of this period on M. Pauly’s blogpost: Les causes de l'effondrement de la civilisation classique à Mayotte, 1680-1820

Dzaoudzi (Mayotte, Petite Terre), Parc de la Résidence des Gouverneurs : Fouille archéologique d’office (2019), Rapport final d’opération. By Michaël Tournadre pg 39-41

Note sur le shungu sha wamaore à Mohéli. Un élément de l’histoire politique et sociale de l’archipel des Comores by Sophie Blanchy, Madi Laguera pg 5-7

Islands in a Cosmopolitan Sea: A History of the Comoros By Iain Bruce Walker pg 84

The Comoro islands: Struggle against dependency in the Indian Ocean. by M. D. D. Newitt pg 27, Islands in a Cosmopolitan Sea: A History of the Comoros By Iain Bruce Walker pg 85-89

Islands in a Cosmopolitan Sea: A History of the Comoros By Iain Bruce Walker pg 89)