Forgotten Cities of the Swahili coast: A history of Pemba in the Medieval Indian Ocean World (ca. 600-1822 CE)

Journal of African Cities: chapter 19

Pemba is a verdant island 60 km off the northern coastline of Tanzania that is home to the densest concentration of stone architecture on the East African coast

Despite its modest size of roughly 1,000 km², Pemba was a Swahili heartland during the Middle Ages. It was divided among several prosperous kingdoms that were deeply integrated into Indian Ocean trade networks. During the Portuguese period, the island developed into a cosmopolitan center with a diverse population, and its agricultural productivity made it the granary of the Swahili coast.

The rich urban history of Pemba was later obscured under Omani rule during the 19th century, when the island was relegated to the role of an agricultural hinterland supplying the elites at Zanzibar. However, recent archaeological discoveries have prompted a reassessment of Pemba’s historiography and its role in pre-colonial Africa’s ancient links with the Indian Ocean world.

This article outlines the history of Pemba from the medieval period to the 19th century.

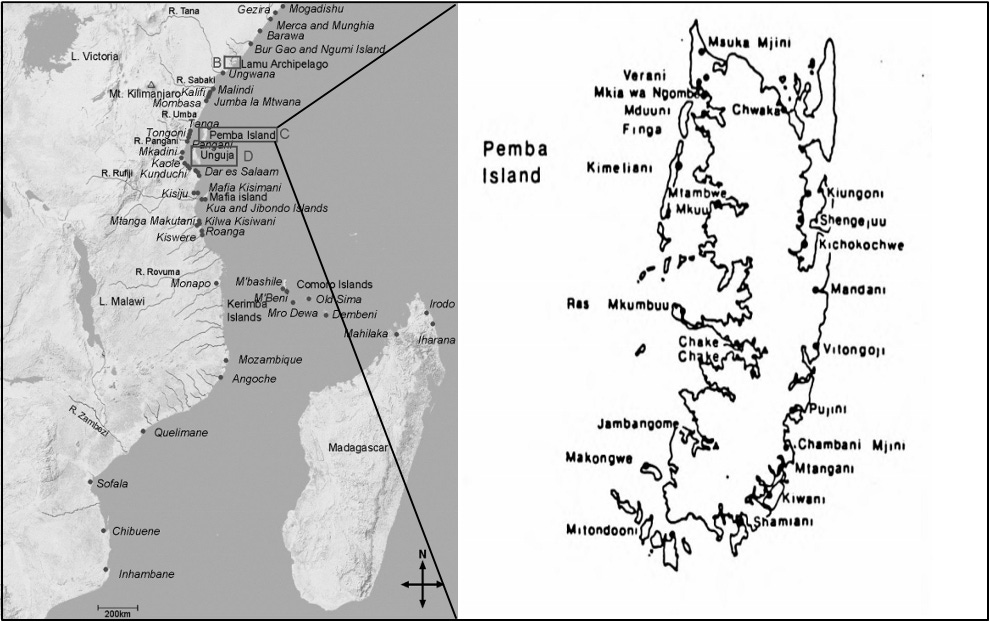

Map of Pemba on the East African coast.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by joining our Patreon community. Subscribe here to read more about African history, download history books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The early history of Pemba (600-1000 CE)

Pemba first appears in written history in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (1st century CE), which describes an island off the East African coast called Menouthias, located about 300 stadia (roughly 30 miles) from the mainland.

According to the historians Horton and Middleton, the description of Menouthias, being low, wooded, and having rivers, as well as its position from the mainland, fits with Pemba. Its inhabitants had sewn boats and dugout canoes, and used basket traps for fishing.1

Several centuries later, the island reappears in the 9th-century work of the Afro-Arab poet al-Jahiz (d. 869), who mentions the home of the ‘Zanj’ on the two islands of Qanbalu/Kanbalu and Lanjuya, which are phonetically linked with Pemba and Unguja (Zanzibar). Qanbalu was visited in 916 by the Abbasid geographer al-Mas’udi, who mentions the presence of a religiously mixed community of “Muslims and Zanj idolaters,” as well as a royal family that spoke Zahjiyya (i.e., the language of the Zanj) and had established their polity in the 8th century.2

Several other writers cite Qanbalu in the following centuries, including Ibn Buzurg in the late 10th century, al-Idrisi in the mid-12th century, and Yakut in the 13th century, often drawing from secondary sources. While these early accounts have been characterized as “wonderfully evocative, often diaphanous and sometimes clearly just fanciful,” they nevertheless indicate that Pemba was home to several complex societies.3

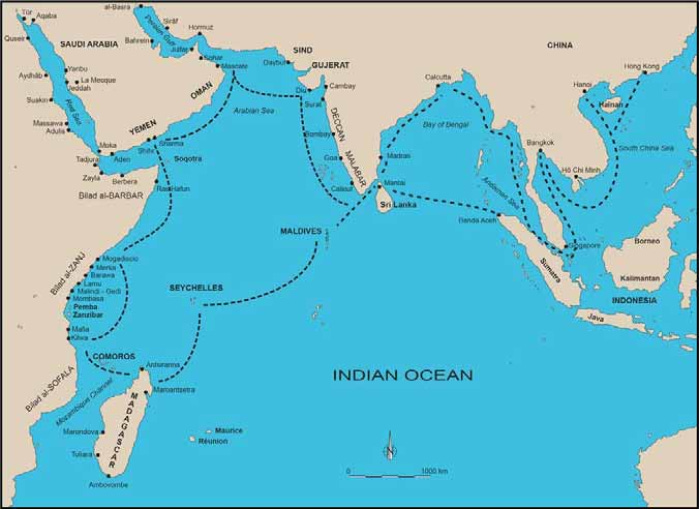

Map of the Indian Ocean world by S. Pradines.

Archaeological research on the island of Pemba has revealed a remarkable density of settlements dating to the late 1st millennium CE.

Material evidence for the Early Iron Age communities, who were part of the eastern expansion of Bantu-speaking groups, is found across the northern coastline and hinterland of Tanzania, where multiple sites contain pottery sherds belonging to the Kwale tradition (200BC-500CE). By the 6th century, this evolved into the ‘Tana Tradition’ or Triangular-Incised Ware (TT/TIW), which is considered the material signature of the Swahili and other Sabaki-speakers, such as the Pokomo, Nyika, and Mijikenda languages.4

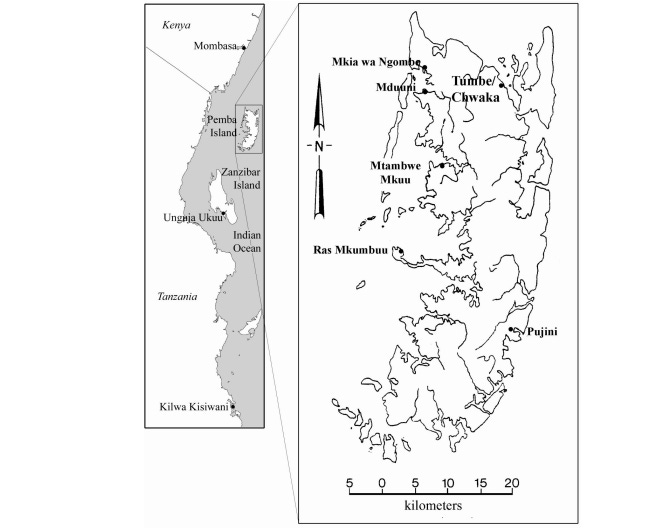

On Pemba, TT/TIW ceramics have been identified in multiple sites, especially along its northern coast, the largest of which was the site of Tumbe (see map below), which covered about 60ha and was settled from the 7th to 10th century. At its height, there were more than 15 similar sites in the surrounding countryside, 9 of which were within 2km of Tumbe. Besides locally produced pottery, there were imported vessels from Arabia, the Persian Gulf, and China.5

Remains of dense mounds of daub with pole impressions indicate that the residents of Tumbe lived in wattle-and-daub structures. Excavations suggest a decentralized and household-based economy, with evidence for glass-bead grinding, as well as copper and iron smithing. Tumbe was later abandoned in the 11th century, alongside other settlements, as the population moved to the stone-towns of Chwaka and Mkia wa Ngombe.6

Map of the East African coastline (left) from Mombasa to Kilwa Kisiwani, and Pemba Island (right), showing settlements mentioned in the article. Map by A. LaViolette and J. Fleisher

The stone-towns of medieval Pemba (1000-1500)

In c. 1050 CE, settlers from the abandoned site of Tumbe founded Chwaka just 50 m nearby. Within a century, it covered 8 ha; by 1300, it measured 12 h, where it remained until abandonment in the early 16th century.

Like most early Swahili urban architecture, the central building at Chwaka was its first mosque, built of Porites coral with a timber roof in the 11th century. A second mosque was built in the 12th century, near the water’s edge, and another in the 13th century. During the 14th century, the first mosque was rebuilt and extended with two side halls and barrel vaults, thus tripling its capacity. A fourth, smaller mosque was later constructed in the 15th century.7

Coral architecture at Chwaka. A) Excavations at the Friday mosque and B) the pillar tomb. images by A. LaViolette & J. B. Fleisher

The thirteenth-fourteenth-century mosque at Chwaka. Image by M. Horton.

The congregation mosque had a cluster of ten stone tombs nearby, including two pillar tombs. There was just one stone house, a single-story structure that is dated to the 15th century. It was surrounded by hundreds of wattle and daub houses, which housed an estimated population of 3-5,000. Excavations yielded a lot of local pottery and a small percentage of imports (about 1-2%) from the Persian Gulf, China, and the Red Sea.8

Chawka mosque, Pemba. Image by Francis Barrow Pearce, ca. 1919.

(left) The original central room of Chwaka’s congregation mosque, after excavation. Image by M. Horton. (right) Packed-earth walls from a house sequence at Chwaka. image by A. LaViolette

From the 11th to 15th centuries, five major stonetowns thrived on the shores of central and northern Pemba, along with eight smaller towns and villages.9 Like most Swahili ‘stone-towns’, these were defined by the presence of a handful of stone mosques, tombs, and elite houses in an otherwise largely wattle-and-daub built settlement. The largest of the stonetowns were Mtambwe Mkuu, Ras Mkumbuu, and Pujini.

Mtambwe Mkuu, near the north-west coast of the island, was settled in the 9th century by farming and fishing communities using TT/TIW ceramics, gradually expanding into a 16 ha settlement of c. 1,000 people before it was abandoned in the 16th century. Among its earliest structures was a timber hall that was rebuilt in stone in the 10th century, along with two stone mosques, eight domestic buildings, a family cemetery, and lime-lined pits for indigo dyeing.10

The domestic sector revealed evidence of shoreline management as early as the 12th century, including a line of mangrove stakes to control erosion. The site also yielded the important Mtambwe coin hoard, consisting of 630 locally minted coins and 8 Fatimid dinars, that were buried in a modest earthen house.

The Mtambwe Mkuu hoard of silver coins, Pemba Island, Tanzania. Image by S. Wynne-Jones.

Ceramic assemblages from Pemba included the distinctive Red-painted and graphite-earthenware that has been found in several distant locales along the east African coast in Comoros. These ceramics were also found as far north as Sharma in Yemen, alongside TT pottery, suggesting the presence of a Swahili diaspora in Yemen. Additionally, chlorite-schist and rock crystal found at Mtambwe point to exchange connections with Madagascar, likely via Comoros.11

The latest of the Fatimid coins was dated to 1066, while many of the names of the local rulers found in the hoard date to the 11th and 13th centuries. Their coiners ruled at the same time as the Kilwa sultans, but after the coiners at Shanga, and their distribution from Zanzibar, Mafia to Kilwa suggests familial ties, as well as the spread of coinage southwards. The hoard speaks to the presence of international merchant activity, notably in the absence of stone dwellings. The discovery of Muslim burials at Mtambwe set out at right angles, suggesting that some of the inhabitants were Shi’ites, lending support to the Shirazi traditions common along the Swahili coast.12

While the 10th-century mosque at Mtambwe was built in Ibadi-style, it was later replaced in the middle of the 11th century by the more conventional Sunni or Shafi‘i type, which is the mainstream practice of most Muslims. There are fragmentary references to Kharijite-Ibadi adherents in Pemba and the southern coast during the early 2nd millennium CE, but their doctrines disappeared by the 13th century. When Ibn Battuta visited Kilwa in 1331, he noted that Swahili Muslims followed the Shafi‘i school of Sunni Islam.13

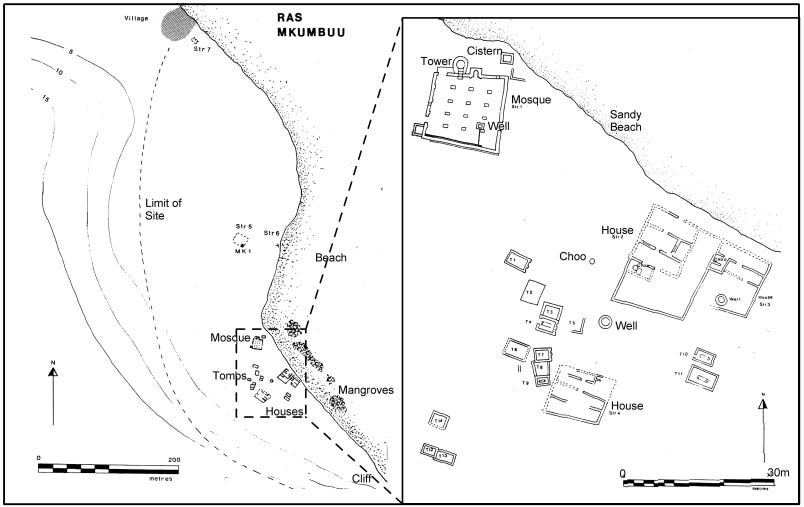

Ras Mkumbuu, on the western coast of the island, had two settlement phases, first in the 10–12th century, when a settlement covering 6ha was established on a low plateau; and in the 14th-16th century, when a settlement about 10 ha large was founded next to the shore.

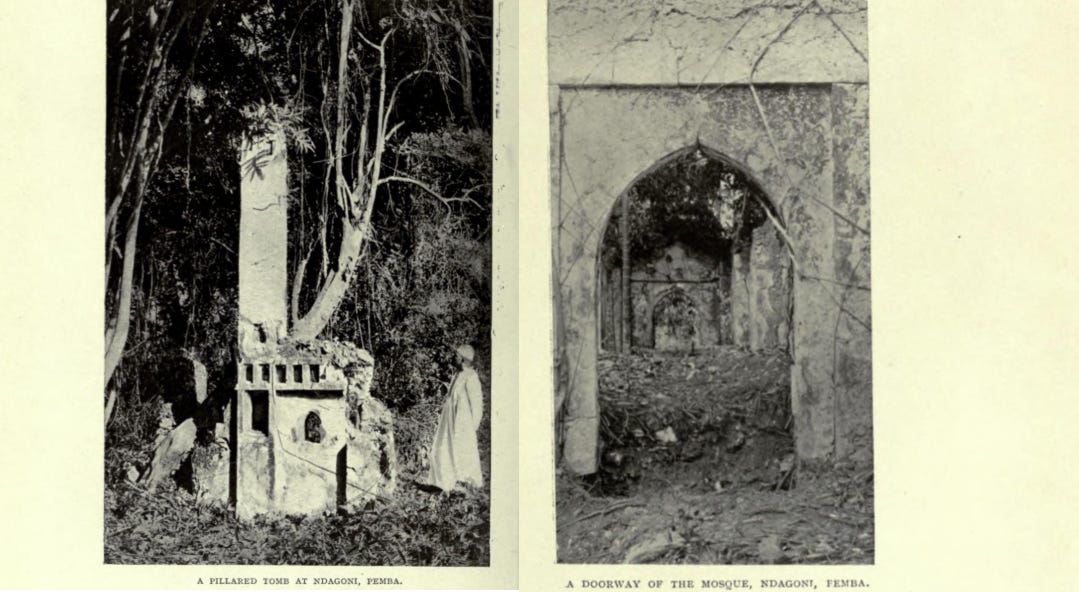

Pillar tomb and mosque at ‘Ndagoni’ Pemba, image by Francis Barrow Pearce, ca. 1919. The site was later identified as Ras Mkumbuu

Plan of Ras Mkumbuu, Pemba Island by Horton & Clark

The early settlement consisted of a series of timber buildings with clay floors and a timber mosque that was burned down and rebuilt with Porites coral during the late 10th century. Some of the early earth and timber houses (about 15) were rebuilt in coral with bonded mud by the 11th century, and a larger mosque was constructed, as well as a large cemetery containing pillar tombs.

Ras Mkumbuu’s numerous stone houses suggest it was an important merchant town. While it overlapped with Mtambwe Mkuu, the absence of red-painted/graphited local wares and Sasanian-Islamic imports indicates different trade connections than its northern neighbour.14

Mosque of Ras Mkumbuu, Pemba. Image by Muhammed Yussuf Khamis

Pillar tombs and mosque (in background), Ras Mkumbuu, Pemba Island.

Interior of the mosque.

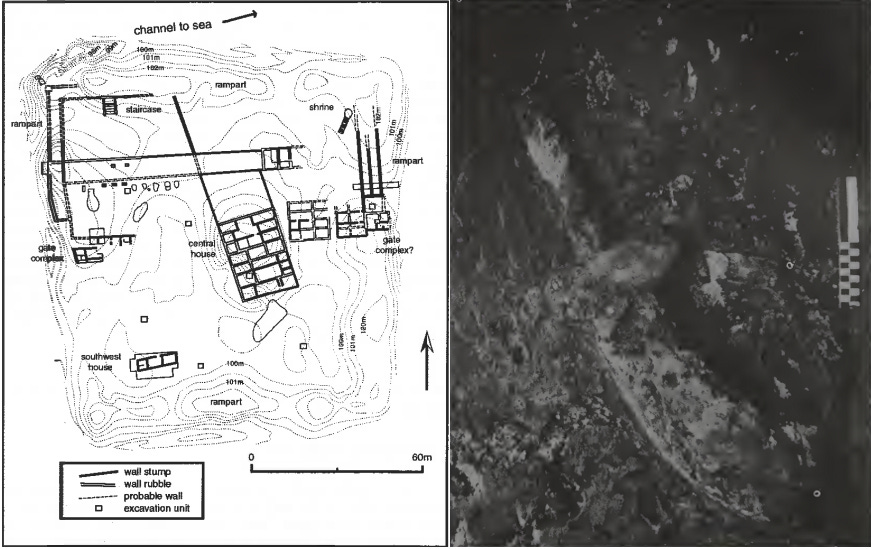

The site of Pujini on the southeast coast was constructed in the 15th/16th century as a fortified settlement. Its defining feature is a rectangular stone rampart surrounding 1.5 ha of open space and structures, including a multi-storied house built in classic 14th-15th century Swahili style. Nearby are the remains of a stone mosque and two wells, containing ETT/TIW pottery.

The rampart comprises three parallel walls and a parapet walk, and its interior was accessed through two gates. Inside that gate were plaster-floored rooms and two buried fingo pots for spiritual protection. Fingo pots are found among groups from the mainland, as well as other Swahili cities. The main stone house included a large zidaka and decorated doorways. In the northeast is a sub-surface shrine to land/sea spirits; open-air steps lead down into a small, domed room, whose walls bear a moulded siwa, a ceremonial side-blown horn, associated with coastal and inland communities. Traditions associate the site of Pujini with a ruler known as Mkame Mdume, who claimed origins from both the Shirazi and the Segeju (on the African mainland). 15

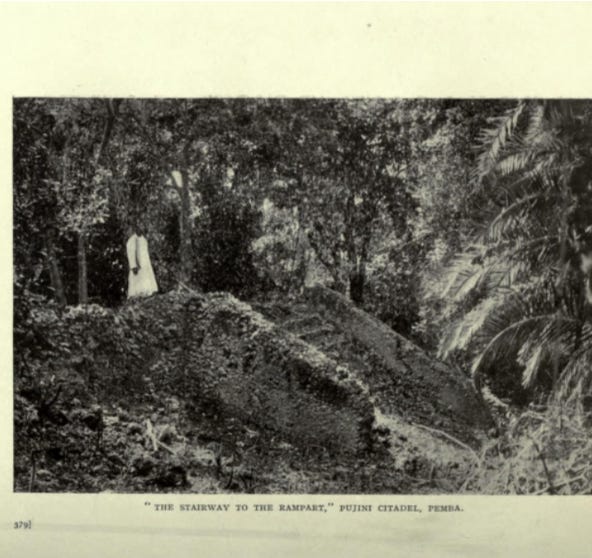

Stairway to the Rampart at Pujini, Pemba. Image by Francis Barrow Pearce, ca. 1919.

Pujini ruins.

Plan of Pujini. Image by A. Laviolette. Plaster relief of a side-blown horn or siwa, another emblem of Swahili kingship, on the ‘shrine’ at Pujini, Pemba Island. Image by James De Vere Allen

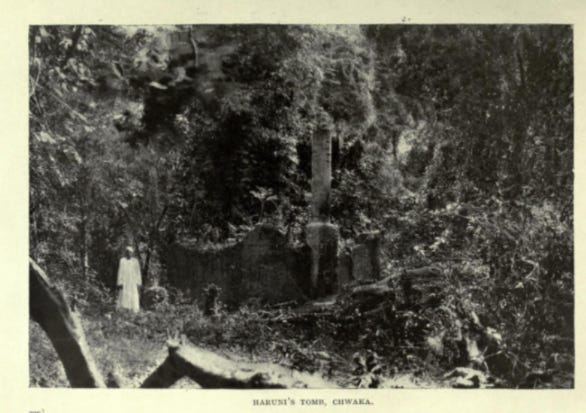

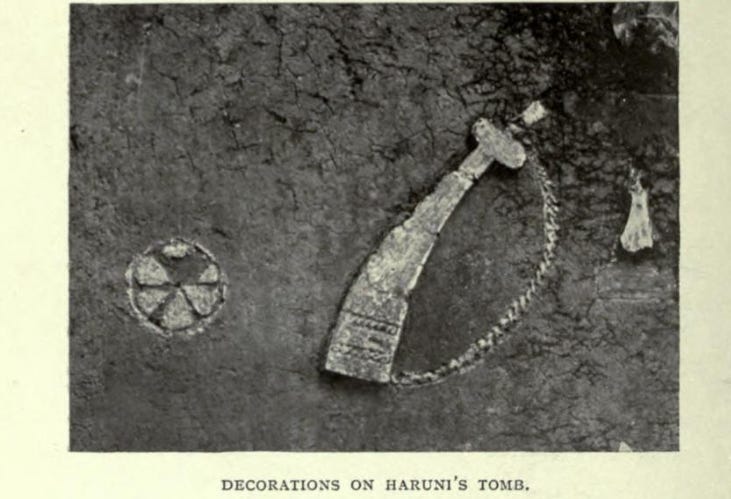

His son was Haruni, whose pillar tomb still survives at Chwaka, and is also decorated with a siwa. Notes on a Portuguese raid in 1520 described a ‘deserted village fortified in the manner of a fortress’; whose ruler had recently fled to Mombasa. Pujini, along with many of the stone towns of Pemba, were abandoned in the 16th century.16

pujini ruins

Haruni’s Tomb at Chwaka. Image by Francis Barrow Pearce, ca. 1919.

(left) 17th-century side-blow ivory horn (siwa). Lamu Museum, Kenya. (right) A man blowing a siwa-type horn in Lamu.

Pemba during the Portuguese period (1500-1750): between the East African mainland and the Indian Ocean world.

Pemba’s towns were described in the earliest Portuguese accounts in the early 16th century, which mention that the island was home to many kingdoms and towns.

In 1505, Pedro Ferreira, a Portuguese Captain at Kilwa, reported that Pemba was divided into five kingdoms, named in local traditions as Twaka, Mkumbuu, Utenzi, Ngwana, and Pokomo or Ukoma, each of which was said to contain seven towns. Twaka is suggested to be ‘Chwaka’, while Pokomo is likely named after the eponymous group from the mainland.17

In 1517, the Portuguese factor Duarte Barbosa, writing more generally about Pemba, Zanzibar, and Mafia, describes their inhabitants as wealthy, wearing silk garments and gold from Sofala, and trading with the coastal cities using their own vessels. The island was noted for its importance in supplying grain to Mombasa and Malindi, rather than as a trading centre.18

An account from 1523 suggests early alliances between one of the rulers of Pemba and the Portuguese, apparently requesting military assistance to reoccupy the Kerimba islands of Mozambique. The same ruler also sent his forces to aid the Portuguese in their sack of Mombasa in 152819

This particular polity would have hosted some Portuguese settlers, who were said to have mistreated the local population, which resulted in a rebellion that briefly forced the settlers out and the king into exile, taking advantage of the appearance of the Ottoman fleet of Ali Bey in 1585 and 1589.20

A Portuguese account from 1592 indicates that their earlier attempt to re-conquer this kingdom (and possibly the whole island) had failed: “Pemba is an illand and about eight leagues from the Shoare, and ten long, plentifull of Rice and Kine, Fruits and Wood: sometime subject to the Portugalls till the pride and lazinesse of some made the people rebell, and could never after be regayned”21

The ruler of Pemba, who had been expelled in 1589, later returned with Portuguese support but was assassinated by his own subjects. His brother, who was in exile in Mombasa and had been taken to Goa (India) in 1595-96 with the promise of restoring him to the throne, returned to Pemba as a Christian convert named Dom Filipe, with a Portuguese wife, Dona Anna, although it’s unclear if he ever assumed the throne. His son, Dom Estevio, was taken to Goa with the hope that he would succeed his father. However, Dom Filipe passed away in 1605, and his kingdom was leased to the king of Malindi, who had aided his return to Pemba.22

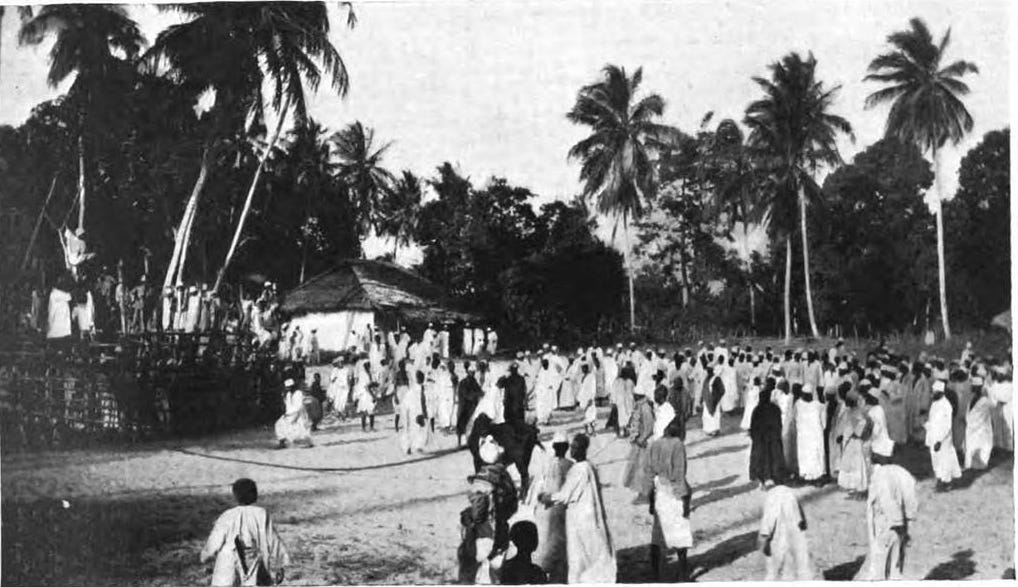

A Pemba bullfight. ca. 1919. Initially thought to be a relic of the Portuguese occupation of the island, the ‘mchezo wa ng’ombe’ (more accurately called ‘bull-baiting) actually bears little resemblance to the Portuguese tauromachia, and likely predated their arrival.23

In 1598-9, the king of Malindi had intervened militarily in Pemba with an army of Swahili and Nyika soldiers from the mainland. The ‘Nyika’ (or Vanika), like the ‘Musungulos’ (or Muzungulos), are catchall terms for groups from the mainland, such as the Segeju, Pokomo, and the Duruma (part of the Mijikenda), who interacted closely with and were integrated into Swahili cities at various points in history. The Nyika of Pemba were settled as agricultural clients of the rulers of Malindi and Pemba; some adopted Islam, intermarried with the local population, and were frequently recruited as soldiers by different factions.24

In late 1608, a ship of the East India Company found the island firmly under Portuguese control. It encountered three ships with 40 sailors near Pemba, which regularly carried out a trade in agricultural products and Indian cloth. Particular mention was made of at least 6 of the 40 sailors who were “pale and white, much differing from the colour of the Moores (Swahili); yet being asked what they were, they said they were Moores.” These likely represented recent migrations of Sharifian families on the coast, especially at Pate, who are mentioned in many 16th-17th century accounts.25

In the Indian Ocean, Portuguese and other European sources of the 16-17th century, make an almost systematic distinction between the “Mouros da terra” (the native Muslims) or “Naturals da costa” (natives of the coast), and the “Mouros da Arabia” (the Moors of Arabia). The term Swahili, which would correspond with the former group, wouldn’t be adopted by the populations known today by this ethnonym until the 18th century, as part of their opposition to the Omani occupation of the coast in 1698-1728, as indicated by the letter from the Queen of Kilwa written in 1711.26

Thus, the Dutch who visited the coast in 1776 refer to the “Sualiers” (Swahili), who were separate from the ‘Arabs’ and Moors, and were inturn distinguished from mainland Africans by their religion and dress.27 French and English accounts of the 18th century emphasised more phenotypical differences. Thus, the French traveler Morice, who visited Kilwa in 1775, describes its sultan (Hasan b. Ibrahim al-Shirazi) as ‘black’ and regards him as an ‘African,’ in opposition to the native ‘Moors’ and Omani ‘Arabs’.28 The English captain Henry Rooke, who visited Mutsamudu (Anjoan/Nzwani) in 1787, describes its rulers and inhabitants as ‘black.’29

In 1631-2, Pemba supported the anti-Portuguese ruler of Mombasa, Dom Jeronimo (Prince Yusuf Hasan), who had settled many of his soldiers from the mainland on the island during his rebellion against the Portuguese. The island is described as having “fourteen large towns besides many small ones.” Parts of it were so densely populated by about 4,000 auxiliaries from the mainland, “that it is necessary to place boundary marks for the natives who seek for land to cultivate.”30

Archaeological ruins from this period include the site of Kichokochwe, located on a small island on the east coast, which contained a well-preserved mosque that was in use until the 1920s, as well as about 11 stone tombs. Another ruined site was Kiungoni, which contained a relatively large mosque similar to the one at Kichokochwe. Material culture from both sites is dated to the late 17th century.31

Mosque of Kichokochwe, Pemba.

In the late 1640s, Pemba was at the head of an anti-Portuguese coalition of Swahili cities, including Zanzibar and Utondwe. In 1651, forces of Pemba, supported by newly arrived ships from the Yarubid ruler of Oman, ravaged the small Portuguese colony at Zanzibar, killing and capturing 50-60 settlers. While the Portuguese forced the queen of Zanzibar into exile, Pemba’s king retained his authority. His successors allied with the rulers of Pate to restrict supplies of grain to Portuguese-controlled Mombasa, reducing it to the point of famine in 1662, 1686, and 1694.32

In 1698, the Swahili and the Yarubi Omanis expelled the Portuguese from Mombasa, but the Omanis were soon resented as much as the Portuguese. Multiple rebellions are reported in Pemba, which had been forced to pay tribute in the form of timber for Omani ships. A complex of Swahili alliances enabled the Portuguese to briefly recapture Fort Jesus in 1728-9, before they too were expelled, and most cities reverted to local rulers.33

Internally, Pemba operated a ranked system, with leaders, known as masheha, in each town or district, with a single paramount chief or diwan. The alawi sharifs, who intermarried with prominent Swahili lineages, also joined the ruling lineage of Pemba, whose king is mentioned in a Portuguese account from 1728 as “bin Sultan Alawi”.34

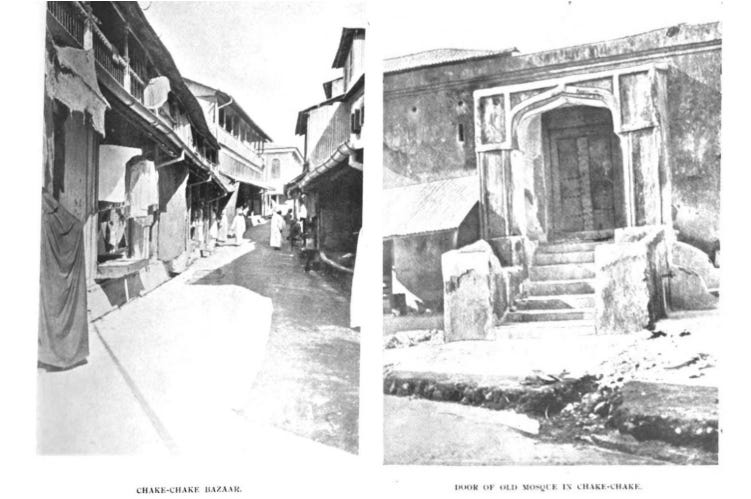

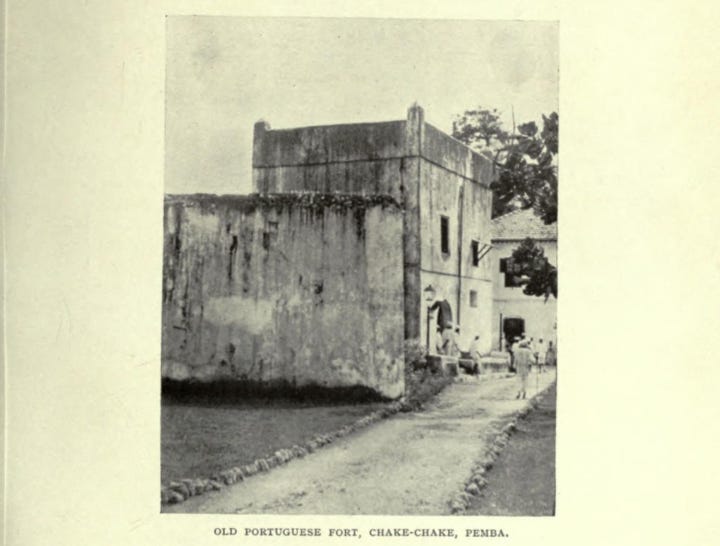

Pemba was considered the granary of the Swahili coast. Between the years 1590 and 1750, various local and regional powers asserted their control of the island, often imposing a grain tribute (makanda) collected from local farmers in client relations with their suzerains. In the mid-18th century, both Pate under Bwana Tamu and Mombasa under Ali bin Othman al-Mazrui claimed suzerainty over the island.35 The fort of Chake Chake was likely constructed during this period, or in the 19th century.36

The Bazaar and mosque of Chake-Chake, Pemba. images by John Evelyn Edmund Craster, ca. 1913.

The fort at Chake-Chake. Mislabeled as a ‘Portuguese fort’ by Pearce (1919), it was, according to Horton and Pradines, built much later in the 18th/19th century.

According to the chronicle of Pate, the city and the Mazrui then shared the “taxes” levied there. Traditions recorded by Charles Guillain in the early 19th century suggest that the Pembans invited the Mazrui to drive off Pate, assassinating its governor in the 1770s. An account from 1811 indicates that Pemba was divided between the Mazrui of Mombasa, the Busaidi of Oman, and the local rulers, who remained independent.37

The growth of Mombasa in the late 18th to early 19th century resulted in increased demand for commodities and grain from Pemba, which transformed the makanda-tribute into a system of dependence more akin to servitude. This was in part enabled by an influx of client farmers from the mainland (waNyika) during the governorship of the liwali Mazrui Abdallah bin Hamed (circa 1814-1823), after a famine in Duruma country. 38

In the early 19th century, East Africa became an important resource for commodities in demand in Europe and America, such as Ivory and cloves, of which Pemba soon became a major supplier. In 1819-22, the island was captured by the Busaid sultan of Zanzibar from the Mazruis, and became the main centre of clove production.39

Over the course of the century, Pemba became increasingly ruralized and was turned into a breadbasket periphery. The memory of Pemba’s ancient urban history was thus reinterpreted in both oral and written accounts, and its centrality in the history of the East African coast was obscured in early historical research on the island.40

“Pemba Isd. Loading cloves.” ca. 1880-1950. British Museum.

‘Mgalawa’ on an outrigger canoe with a sail. ca. 1880-1950. British Museum.

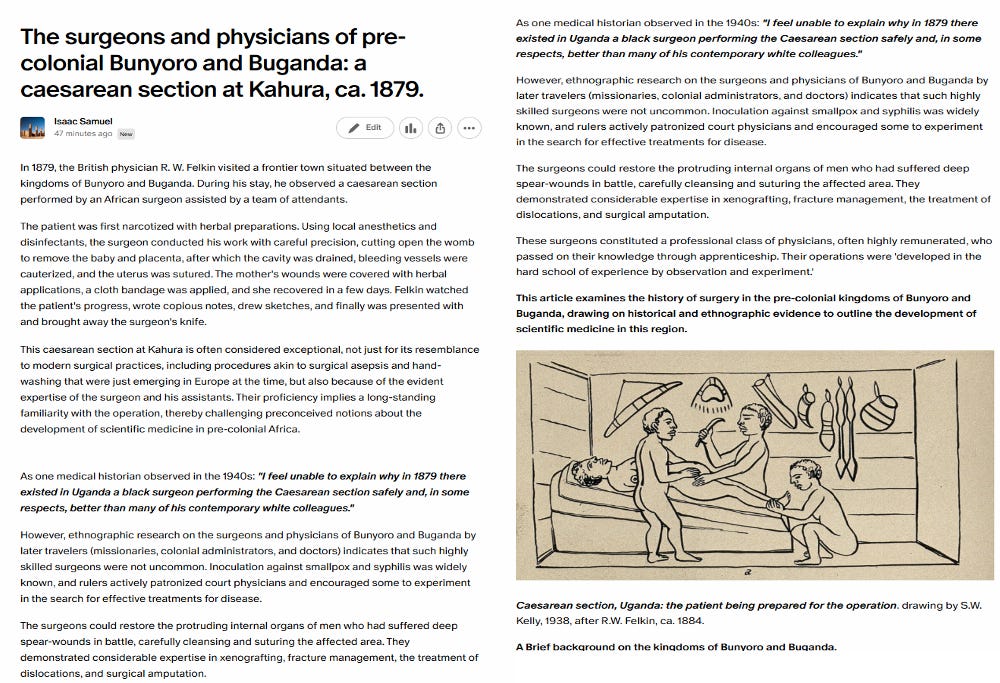

In 1879, the British physician R. W. Felkin observed and recorded an exceptional account of a caesarean section performed by an African surgeon assisted by a team of attendants in what is today central Uganda.

The history of surgeons and physicians of pre-colonial Bunyoro and Buganda is the subject of my latest Patreon article. Please subscribe to read more about it here:

The Swahili: The Social Landscape of a Mercantile Society, by Mark Horton, John Middleton, pg. 33

The East African Coast. Select Documents from the First to the Earlier Nineteenth Century by Greville Stewart Parker Freeman, pg 14, 17. The Swahili: The Social Landscape of a Mercantile Society, by Mark Horton, John Middleton, pg 65, 75

Swahili Archaeology and History on Pemba, Tanzania: A Critique and Case Study of the Use of Written and Oral Sources in Archaeology, by Adria LaViolette, pg 132, 135-137

The Archaeology of Tanzanian Coastal Landscapes in the 6th to 15th Centuries AD: The Middle Iron Age of the Region by Edward John David Pollard, pg 43-45. Ceramics and the Early Swahili: Deconstructing the Early Tana Tradition by Jeffrey Fleisher and Stephanie Wynne-Jones. The Swahili: reconstructing the history and language of an African society, 800-1500 by D.Nurse

The early Swahili trade village of Tumbe, Pemba Island, Tanzania, AD 600–950 Jeffrey Fleisher and Adria LaViolette.

The Urban History of a Rural Place: Swahili Archaeology on Pemba Island, Tanzania, 700–1500 AD By Adria LaViolette and Jeffrey Fleisher pg 439-446

The Swahili World, edited by Adria LaViolette, Stephanie Wynne-Jones, pg. 235

Developments in Rural Life on the Eastern African Coast, a.d. 700–1500 by Adria LaViolette & Jeffrey B. Fleisher, pg. 390-395.The Urban History of a Rural Place: Swahili Archaeology on Pemba Island, Tanzania, 700–1500 AD By Adria LaViolette and Jeffrey Fleisher pg 447-453

Zanzibar Archaeological Survey 1984-5 by Mark Horton and Kate Clark

The Swahili World, edited by Adria LaViolette, Stephanie Wynne-Jones, pg. 232

The Swahili World, edited by Adria LaViolette, Stephanie Wynne-Jones, pg. 233, 312

The Swahili World, edited by Adria LaViolette, Stephanie Wynne-Jones, pg. 51, 57-60

The Swahili: The Social Landscape of a Mercantile Society, by Mark Horton, John Middleton, pg. 66-68. Historic Mosques in Sub-Saharan Africa From Timbuktu to Zanzibar By Stéphane Pradines, pg 152, 157.

The Swahili World, edited by Adria LaViolette, Stephanie Wynne-Jones, pg. 234

African Historical Archaeologies edited by Andrew M. Reid and Paul J. Lane, pg 138-152

The Swahili World, edited by Adria LaViolette, Stephanie Wynne-Jones, pg. 237. The Urban History of a Rural Place: Swahili Archaeology on Pemba Island, Tanzania, 700–1500 AD By Adria LaViolette and Jeffrey Fleisher pg. 438

African Historical Archaeologies edited by Andrew M. Reid and Paul J. Lane, pg 152, Swahili Origins Swahili Culture & the Shungwaya Phenomenon By James De Vere Allen, pg 29

The East African Coast. Select Documents from the First to the Earlier Nineteenth Century by Greville Stewart Parker Freeman, pg 133-134. The Urban History of a Rural Place: Swahili Archaeology on Pemba Island, Tanzania, 700–1500 AD By Adria LaViolette and Jeffrey Fleisher pg 434-435

The Portuguese Period in East Africa By Justus Strandes pg 103-104, 107

The Portuguese Period in East Africa By Justus Strandes, pg 123, 137

The East African Coast. Select Documents from the First to the Earlier Nineteenth Century by Greville Stewart Parker Freeman, pg 150

The Portuguese Period in East Africa By Justus Strandes, pg 166-168.

Bull-Baiting in Pemba by Sir John Gray

Les cités-États swahili et la puissance omanaise, 1650-1720 by Thomas Vernet, pg 83, 262, 528-529 on the Nyika , see: Swahili Origins: Swahili Culture & the Shungwaya Phenomenon By James De Vere Allen pg 90-91, 123, 132

Les cités-États swahili et la puissance omanaise, 1650-1720 by Thomas Vernet, pg 168. The journal of John Jourdain, 1608-1617, describing his experiences in Arabia, India, and the Malay Archipelago, pg 40-42

Les cités-États swahili et la puissance omanaise, 1650-1720 by Thomas Vernet, pg 6-7, 196. Ivory and Slaves in East Central Africa: Changing Pattern of International Trade in East Central Africa to the Later Nineteenth Century by Edward A. Alpers pg 73

The Dutch on the Swahili Coast, 1776-1778: Two Slaving Journals, Part I by Robert Ross and Fk. G. Holtzappel, pg. 323, 333)

The French at Kilwa Island: An Episode in Eighteenth-century East African History, pg G. S. P. Freeman-Grenville, pg 11-12, 42, 45-46. Les cités-États swahili et la puissance omanaise, 1650-1720 by Thomas Vernet, pg 395-296. A Revised Chronology of the Sultans of Kilwa in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries by Edward Alpers. pg 146-147

Travels to the Coast of Arabia Felix and from Thence by the Red Sea and Egypt to Europe by Henry Rooke pg 21-29

The East African Coast. Select Documents from the First to the Earlier Nineteenth Century by Greville Stewart Parker Freeman, pg 182

Zanzibar Archaeological Survey 1984-5 by Mark Horton and Kate Clark, pg 21-22

Les cités-États swahili et la puissance omanaise, 1650-1720 by Thomas Vernet, pg 301-305, 352, 364

Les cités-États swahili et la puissance omanaise, 1650-1720 by Thomas Vernet, pg 374-375, 377, 382

The Swahili: The Social Landscape of a Mercantile Society, by Mark Horton, John Middleton, pg. 169, Les cités-États swahili et la puissance omanaise, 1650-1720 by Thomas Vernet, pg 165

Les cités-États swahili et la puissance omanaise, 1650-1720 by Thomas Vernet, pg. 287, 333, 336-7.

Zanzibar Archaeological Survey 1984-5 by Mark Horton and Kate Clark, pg 17. From Zanzibar to Kilwa : Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Omani Forts in East Africa By Stephane Pradines pg 50-52

Les cités-États swahili et la puissance omanaise, 1650-1720 by Thomas Vernet, pg. 467-468, The East African Coast. Select Documents from the First to the Earlier Nineteenth Century by Greville Stewart Parker Freeman, pg 211, 261

Les cités-États swahili et la puissance omanaise, 1650-1720 by Thomas Vernet, pg. 338, 492, 528

The Swahili: The Social Landscape of a Mercantile Society, by Mark Horton, John Middleton, pg. 85, 88. The Battle of Shela: The Climax of an Era and a Point of Departure in the Modern History of the Kenya Coast by Randall L. Pouwels pg 364, n.4

The Urban History of a Rural Place: Swahili Archaeology on Pemba Island, Tanzania, 700–1500 AD By Adria LaViolette and Jeffrey Fleisher pg 436