Origins and Development of Swahili Architecture (ca. 500-1900 CE)

The East African coast, also known as the Swahili coast, is well known for its picturesque ruins of stone houses, mosques, tombs, and town walls, which dotted the 2000-mile coastline from southern Somalia to northern Mozambique and Madagascar.

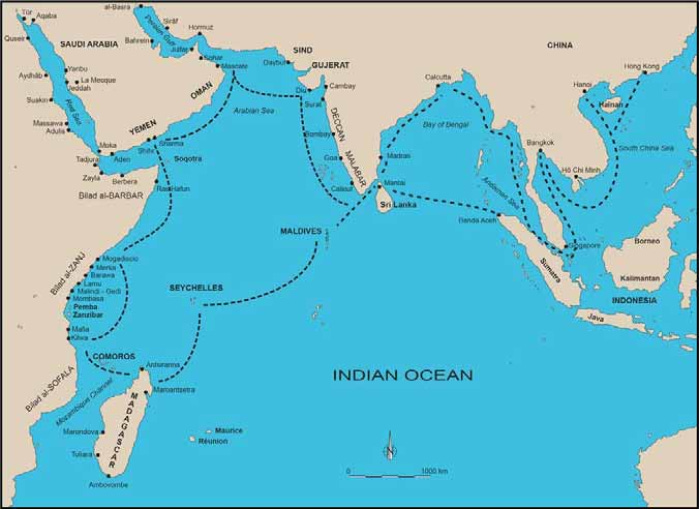

Swahili urban culture, and the built environment as its most visually dominating material testament, developed around Indian Ocean trade networks that linked East Africa to the Mediterranean, Arabia, India, and China during the Middle Ages. When the Portuguese captain Vasco da Gama first reached the Swahili coast in 1498, he was astounded to find well-developed urban centres with buildings of “stone and mortar, with windows and terraces like those of Spain.”

The lime-plastered coral-stone architecture of the East African coast was a characteristic feature of medieval Swahili settlements. It was constructed by the elite Swahili merchant class to serve as symbols of their position and status within the cosmopolitan urban community, and is today considered one of the most recognisable architectural styles of pre-colonial Africa.

This article outlines the history of Swahili architecture and examines its origins and development since the Middle Ages.

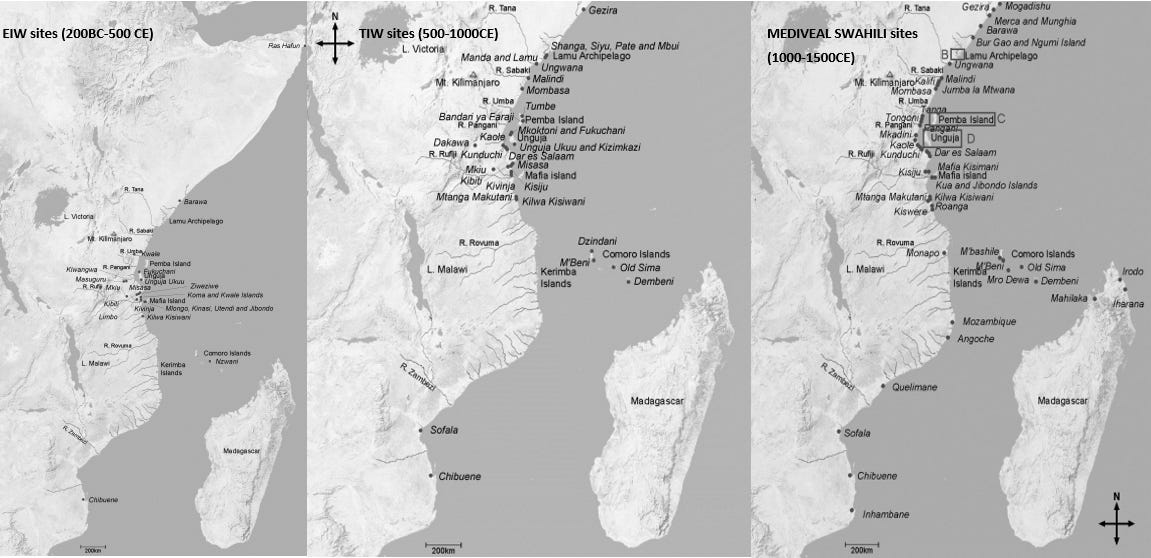

Map of the medieval East African coast.1

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Origins of Swahili architecture in the pre-Islamic period: the case of Mafia, Unguja, and Tumbe. (ca. 300-1000 CE)

Medieval Swahili society was heterogeneous, incorporating populations from diverse backgrounds, all of whom came to share the same language, religion, and architecture.

During the late first millennium CE, coastal and hinterland societies in eastern Africa were united in the production and a shared ceramic tradition known as ‘Tana Tradition’ or Triangular-Incised Ware (TT/TIW) from the 6th to 10th century CE. These in turn evolved out of the ‘Early Iron Working’ pottery (EIW), also known as Kwale wares (200BC-500CE) of Eastern Bantu-speaking communities, whose Sabaki branch includes the Swahili, Comorian, and Mijikenda languages.2

Written sources that document contact between East African coastal societies and the western Indian Ocean world since the 1st century Roman description of the metropolis of Rhapta do not include descriptions of coastal architecture until the late 1st millennium. The account of Buzurg ibn Shahriyyah (900–953 AD) mentions that the town of “Qanbalu” (presumably on Pemba) was fortified with a stone wall, indicating the presence of stone architecture on the coast by the 10th century.3

Archaeological evidence from the older Swahili settlements suggests that most buildings were initially constructed with wattle and daub, and thus left few traces save for post-holes and daub fragments with timber impressions. However, a few elite structures were also built with coral, especially during the late 1st millennium CE.

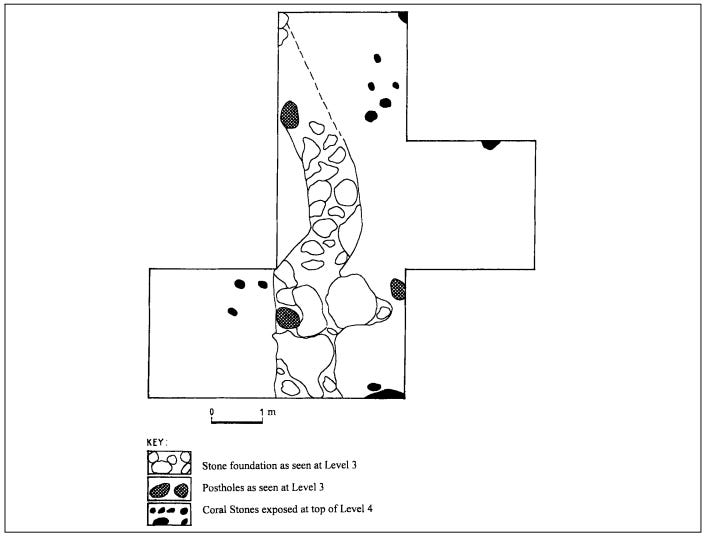

Excavations at Juani on Mafia Island recovered Kwale pottery and iron slag next to a possible stone wall or foundation of a house constructed from coral rubble bonded in clay. The structure also contained postholes, which are present in other sites as remnants of timber beams that supported a roof. On the basis of its stratigraphic position below a horizon containing Kwale pottery (which has been dated on Mafia and Kwale Islands to the 3rd century CE), this structure may be the earliest known example of a stone house or wall on the East African coast.4

Coral stone foundations or walls of a structure at the Juani Primary school site, Mafia, Tanzania. Image by F. Chami

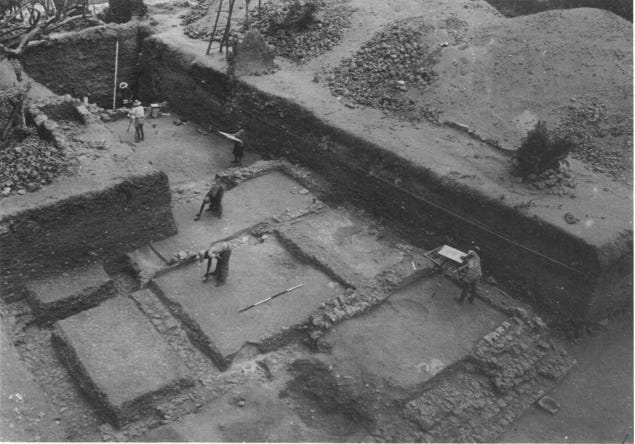

The architecture of the early Swahili site of Unguja Ukuu on Zanzibar island, which was first settled between 500-750 CE, likely consisted of daub and wattle buildings, as indicated by the presence of clay floors, traces of daub, and post-holes.5 Between 750-950 CE, Unguja had developed into a major coastal centre, though most structures were still built with daub and wattle, as indicated by recent excavations which uncovered the remains of an earthen house built in the 8th century.6

However, between the 9th and 10th centuries, a large, elaborate building (labeled ‘Unit M’) was constructed that contained a stone foundation and a stone veranda of coral rag. The structure appears to have an orthogonal layout, and its function was likely secular. Traces of daub but not lime in the soil deposit surrounding the house indicate that clay might have been used as bonding material.7

Remains of a large building at Unguja Ukuu, Zanzibar, Period Ib (750-950 CE) showing a coral stone veranda and stone foundation. Image by A. Juma.

Unguja was contemporaneous with a number of early Swahili sites along the coast, including Shanga and Manda in the Lamu archipelago (Kenya); Tumbe on Pemba Island (Tanzania), and Chibuene in Mozambique.

These sites were home to a small community of both local and foreign Muslims, as indicated by the presence of imported Islamic wares, a few muslim burials, and locally minted silver coins at Shanga. There are also accounts describing the movement of persecuted muslim factions such as Ibadis and Shiʿites who sought refuge on the east African coast between the 8th and 12th centuries.8

However, Swahili societies would remain predominantly non-Muslim as late as Al-Idrisi’s 12th-century account which mentions ritual experts (mganga) in Mulanda (Malindi) and describes Barawa (Brava in Somalia), as “the last in the land of the infidels, who have no religious creed but take standing stones, anoint them with fish oil and bow down before them.”9 The excavators of Unguja also found “no clear evidence for ascribing the religious orientation of the settlement’ during this period.”10

The site of Tumbe on Pemba Island was a large settlement covering about 20-30ha that was occupied from 600-1000CE. Excavations uncovered the remains of two large houses indicated by large quantities of daub with multiple pole impressions, suggesting wattle-and-daub structures with mangrove roof beams and thatched roofs. Dated material from the site indicates that the houses were constructed ca. 770-980 CE.11 The layout of the buildings may have been orthogonal, but their function remains unclear, much like ‘Unit M’ in Unguja.

Traces of baked mud with imprints of beams, poles, and lashings came from 9th- to 10th-century sites of Dembeni and Sima in the Comoro Islands. The mud plasters covering these frameworks had corner pieces, indicating that the houses were rectangular.12 Evidence for rectilinear, and possibly flat-roofed, earthen houses has also been found at Manda and Shanga in Kenya, dating to the 9th century, the latter of which also contained a monumental secular building similar to that found at Unguja 10

Map of the Lamu archipelago showing Shanga and other Swahili settlements. Image by Thomas H. Wilson

Shanga, Kilwa, and the Evolution of Swahili Architecture from the 8th to the 14th Century.

The site of Shanga in the Lamu archipelago has some of the best-preserved stratigraphy in eastern Africa. Unlike Uguja and Tumbe, which were abandoned in the 11th century, Shanga's uninterrupted occupation from the mid-8th to the early 15th century provides an opportunity to study the development of the Swahili house.

The early settlement consisted of an open central enclosure accessed through seven gateways, with the domestic areas forming a doughnut around its edges. The first domestic buildings were built on a framework of small sticks covered in a thin daub infill. In the mid-9th century, a massive timber hall was constructed with a square plan. This structure was replaced in the early 10th century by a square stone building built from undersea-quarried Porites coral, shaped and bonded in red mud with lime plaster facing. These buildings had raised floors and monumental stairs. In the 11th century, the buildings were robbed, and the central enclosure lost its formal existence as it was encroached by domestic buildings.13

The timber hall at Shanga with the principal post pits excavated out. Image by M. Horton.

. The porites building at Shanga during excavation. Image by M. Horton.

In the 12th century, red-earth daub walls appeared, enclosing substantial earth-fast timber uprights. The buildings were rectangular, with a simple plan of parallel rows of rooms with an attached courtyard. Over time, these buildings became more elaborate, with up to five rows of rooms, but also greater use of coral in the daub walls. Lime plaster was used to face the walls, and by the early 14th century, lime replaced mud as a bonding agent for the stone houses built before the town was ultimately abandoned in the 15th/16th centuries.14

The first mosque at Shanga was constructed in the late 8th century. It was a small rectangular timber building with no mirhab (its identification as a mosque is based on the later structures built above it). This was rebuilt and expanded six different times with timber mosques until the 10th century, when a seventh mosque was built with Porites coral bonded in mud, which had side pilasters ending in pillars to support a thatched roof. This structure, which also lacked a mihrab, was destroyed in the 11th century, alongside other monumental buildings mentioned above, and was replaced by another stone mosque with a mihrab and inscriptions in Kufic dated to 1150 CE.15

Excavations within the prayer hall of mosque J (ca 1000 CE), showing the plan of mosque H (ca. 900CE), and the postholes of mosques E (phase 2) F, and G (ca. 900CE). image and captions by M. Horton

Shanga Mosque of the Pillar, dated to the 13th/14th centuries. Image by Thomas H. Wilson.

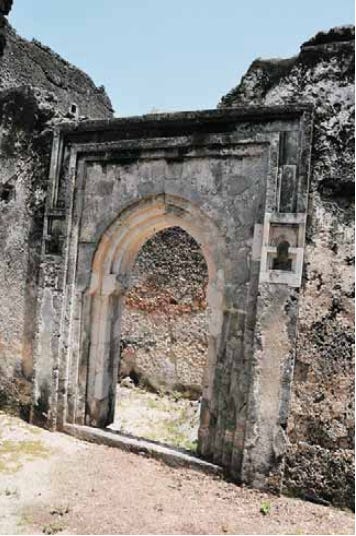

The period of the 11th through the 13th centuries is marked by rapid population increase concomitant with notable growth in the number and size of settlements, as well as increased building activity using Porites coral. The 13th century was a period of transition in which Swahili masons abandoned the use of blocks of Porites sea coral and preferred ashlar blocks of fossil coral (coral rag). The walls were built with irregular ashlar blocks of coral limestone held by a framework in coral concrete, with porites coral now reserved for fine sculptures and door frames.16

Pottery traditions became less uniform and more regionalised/localised, with two styles of local handmade wares emerging on the northern and southern coasts between the 10th and 13th centuries. The former was known as the ‘mature Tana tradition’, while the latter was known as the ‘Plain ware’. In the 13th century, another tradition known as the ‘Swahili ware’ spread from the northern to the southern coast as far south as Mayotte in Comoros. By the 14th-15th centuries, multiple pottery traditions could be found at a single site, suggesting a professionalisation of crafts in response to changing local tastes.17

Fresh marine coral door frame in the palace of Songo Mnara a 15th-century Swahili site. Image by S. Pradines

Construction techniques evolved from the use of small blocks of coral (both fossilised and sea coral) bound by earth during the late 1st millennium, to well-cut blocks of Porites coral bound with lime mortar after the 11th century. While the former is a building technology that’s original to many societies in the Indian Ocean world since antiquity, the origins of the latter type of building technology are still a subject of debate among archaeologists.

According to Mark Horton, it was associated with the Fatimid expansion in the Red Sea region, while Stephane Pradines attributes it to Abbasid mariners in the western Indian Ocean, ultimately originating from the Maldives. Whatever its origins, Porites was later replaced with coral rag, likely as a result of local developments tied to increased demand for elite construction.18

Map of the Indian Ocean world by S. Pradines.

‘Mega Wall’ at Manda, Kenya. Image by Thomas L. Wilson.

Sites that had flourished in earlier centuries were abandoned or declined sharply at this time: eg, Tumbe and Unguja, as well as Chibuene (in Mozambique). Other sites such as Shanga, Manda, Kilwa, Malindi, and Old Sima (in Nzwani) were invariably transformed.

The Swahili now appear more frequently in external texts, virtually all are described as ‘pagan’ societies, at least until the 13th century, and some were ruled by Kings (wafalme) while others were ruled as republics. This period coincides with significant shifts and population movements in the western Indian Ocean, as well as the so-called Shirazi migrations and their intermarriages with local ruling lineages.19

The few internal records from this period are mostly derived from inscriptions on coins and the mihrabs of a few mosques that provide evidence for a Muslim community likely comprised of local converts.

Silver coinage, which was first minted at Shanga in the 9th century, spread to Pemba (found in an earthen house at Mtambwe Mkuu) and Kilwa in the 10th century, all inscribed with names of local rulers. The discovery of the silver hoard of Mtambwe in the absence of stone dwellings, along with finds of ‘TT’ wares and red-painted pottery similar to that found in Comoros and in Sharma (Yemen), points to the presence of international merchant activity at the site.20

At Kilwa, earthen structures were characteristic of its earliest settlement phases since the 9th century, with two rectangular wattle and daub buildings and a timber mosque dated to the 10th century. Around 980 CE, a circular structure of Porites coral was built that contained coins of Ali bin al-Hasan, the first known ruler of Kilwa.

Like in Shanga and Unguja, there's evidence for destruction at Kilwa in the 11th century when this stone structure was demolished and later turned into a construction site containing lime kilns. Around the same time, the original timber mosque was rebuilt with coral, but would remain the only stone structure in Kilwa until the 13th/14th century construction of the two palaces, Husuni Ndongo and Husuni Kubwa.21

Mark Horton attributed the discontinuities in Kilwa and Shanga archaeological sequences of the 11th century to the convergence of local and external upheavals. The former of which was associated with competition between Ibadis and Shafi'is in Kilwa, mentioned in 12th-century accounts, and wider shifts in Indian Ocean trade. The recovery of Kilwa and other Swahili cities during the 14th century, as indicated by substantial construction in coral, is explained by the episodic model of urban development marked by boom and bust cycles, in which a city’s residents scatter or converge depending on the sociopolitical circumstances in the town.22

Description of Swahili architecture:

Houses and Palaces

The classical form of domestic and palatial architecture of the East African coast was largely developed during the 14th and 15th centuries as a unique and coherent building tradition that would continue into the modern period. East African coastal settlements traditionally comprise a continuum of domestic structures, from houses built in stone to those built of earth, timber, and thatch.

When Ibn Battuta arrived at Kilwa in 1331, he stated that it was: “among the most beautiful of cities and most elegantly built. All of it is wood, and the ceiling of the houses are of al-dis (reeds).” This account is corroborated by archaeological evidence from Kilwa during this period, which at the time only contained a handful of stone structures, as extensive building of domestic structures in coral began at the end of the 14th century.23

Portuguese accounts also indicate that the majority of coastal cities contained earthen houses between the stone houses, the latter of which could have thatched roofs or flat roofs. In his description of the Swahili city of Mombasa in 1505, Hans Mayr mentions lime-plastered, three-storied stone dwellings, in between which were wooden houses with porches and stables for cattle. These earthen houses also share some similarities in plan and spatial organisation with stone-built houses described below, featuring orthogonal layouts and multiple rooms that served different functions.24

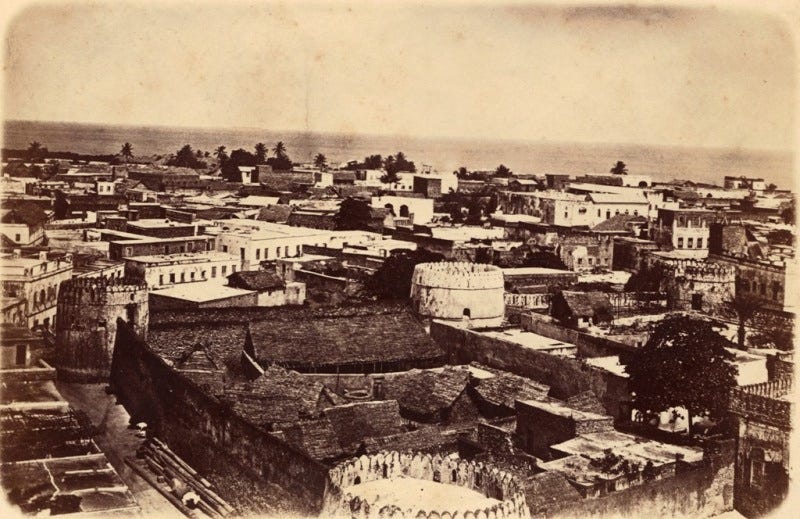

Thatched structures in the center of stone-town. ca. 1875, by John Kirk, Oman&Zanzibar virtual museum

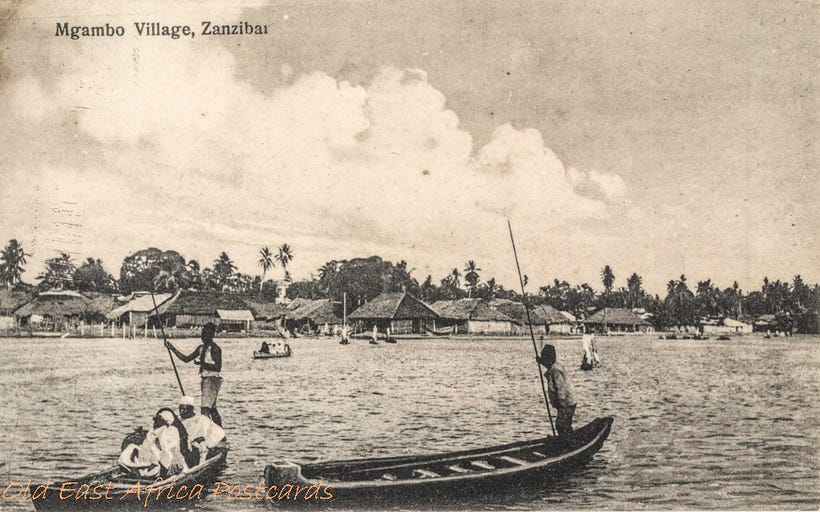

Thatched houses in the N'gambo quarter of Zanzibar, Tanzania.

Domoni, Nzwani (Anjouan), Comoros. ca. 1920, Quai Branly.

Masonry construction along the eastern African coast was material and labour-intensive, involving the quarrying of fossilised coral rag, the burning of coral stone to make lime for cement and plaster, and the cutting of mangrove and other hardwoods for roof beams.

Walls were thick and substantial, constructed using coral rag stone bound together with lime mortar, which was also used to plaster all surfaces. Rooms were long and narrow due to the spanning capacity of the mangrove poles and squared timbers used in roof construction, limited to between 1.80 and 2.80 m. Houses followed a standard plan and arrangement of rooms as a contiguous sequence of parallel spaces.25

A kiln for making lime cement used to bind the dry blocks of coral-rag in southern Tanzania. Image by S. Wynne-Jones

Coral rag architectural ruins at Songo Mnara, Tanzania. Image by Jeffrey Fleisher

Gedi ruins, Kenya.

The houses could be single or multi-storey structures built as inter-linked clusters forming what has been referred to as ‘complex houses’, containing multiple units that formed dense, continuous blocks accessed through narrow passages. These mostly windowless homes featured interior courtyards to allow light and air to enter the inner spaces.

The largest houses and palaces contained sunken courtyards, internal toilets and bathrooms with carefully constructed drains that emptied into deep latrines, wall niches and platforms for holding ceramic pots and porcelain, and multiple rooms identified as kitchens, storerooms, sleeping areas, and inner courts.26

Construction of these complex houses would have involved cooperation and joint planning, implying strong family or social bonds between residents.

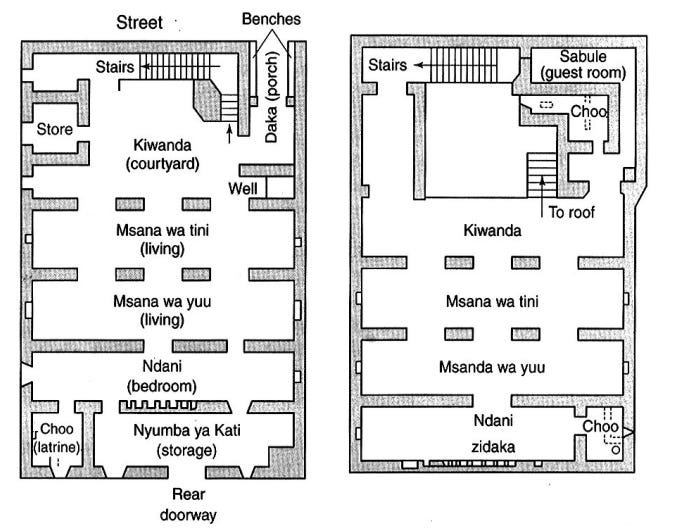

Ethnographic research from later periods suggests that, as in other parts of the Islamic world, Swahili houses followed an intimacy gradient that led from public male-centred spaces to more private female-centred spaces. The houses were entered through a porch (daka) with built-in stone benches (baraza) flanking the entryway. The interior courtyard (kiwanda) was accessed via a carved wooden door. This in turn led to a series of interior passages, vestibules (tekani), a reception room (sabule), the first gallery (msana wa tini), the second gallery (msana wa yuu), and the innermost room (ndani).27

(left) Excavated house block at Gede showing interlocking plans of individual houses. (right) Idealised layout of the Swahili stonehouse, by L. Donley-Reid

Plan of a typical two-storey Swahili stone house in Lamu. The ground floor was built in the 18th century, and the second storey in the 19th century. images by E. Pollard

exterior and interior of the ‘Swahili house museum’ an 18th-century Waungwana-type residence in Lamu that was restored recently.

Except for the elite structures at Kilwa, the Jumbes of Nzwani (Anjouan), and the palaces of Ngazidja (Grande Comore), most of the structures dubbed palaces at Swahili sites tend to be more complex versions of the surrounding architecture. They are usually massive two-storey structures with multiple rooms and highly decorated interiors. They can be found in many of the largest settlements, most notably at Songo Mnara, Gedi, Pate, and Kua.

Kavhiridjewo palace ruins in Iconi, dated to the 16th-17th century. Image by Charles Viaut et al

Ruins of the Husuni Kubwa Palace of the 14th-century ruler of Kilwa Ḥasan bin Sulaymān. image by National Geographic

Aerial view of the Makutani Palace in Kilwa Kisiwani, Tanzania. Image by E. Ichumbaki

Stepped court in the ‘Palace’ at Songo Mnara. Image by S. Wynne-Jones

The ‘audience court’ at Husuni Kubwa, Kilwa Kisiwani, Tanzania. Image by S. Wynne-Jones

‘Palace’ at Kua, Tanzania.

The Mosques:

The early mosques in the Swahili world differ from mosque architecture in the central Islamic lands, where courtyard mosques are widely found. Their north-west orientation and elaborate mihrabs with kufic inscriptions indicate affinities with contemporary mosques in Yemen, Oman, and Siraf.28

All the early mosques were hall-like structures, and it seems that the form, created for timber mosques made of earth-fast upright timbers, was translated into stone buildings. The mihrab was normally deeply recessed and decorated as found at Shanga, Kizimkazi, and Tumbatu. Where ‘Swahili style’ early mosques have been found in the Middle East at Siraf and Sharma, they may have been built to serve the resident African Muslim population in the diaspora, which seems to be indicated from finds of East African ceramics at these sites.29

Mosque of Kizimkazi in Zanzibar, Tanzania. An inscription decorating the qiblah wall of the mosque was dated to 1107.

The typical mosques of the 11th-13th century period feature a rectangular prayer hall built of Porites coral, with four or six columns (sometimes in stone, but more often in timber), side doorways, often arched with apex nicks, and side and corner pilasters that supported a thatched roof. They featured both plain and elaborate mihrabs with dated inscriptions. By the 14th century, Porites coral was replaced with coral rag and lime construction, and many of the older mosques were greatly expanded.30

Great mosque of Kilwa. Image by 360Cities.

Main mosque of Takwa, Kenya. Image by National Museums of Kenya.

Mihrab of the South Mosque at Manda. Image by Thomas H. Wilson

Vaulting first appears in the construction of the mosque of Fakhr ad Din in Mogadishu (ca. 1272) and later spread southwards, particularly at Kilwa Kisiwani, where it was first used at the palace of Husuni Kubwa and then for the extension to the Great Mosque in the 14th century. It was thereafter used at multiple sites in both mosque and tomb architecture, dated to the 15th century. Cylindrical tower minarets also appear early in the mosques of Mogadishu and Barawa, while those that taper upwards were built at Shela, Mombasa Old Town and Mbaraki, and Zanzibar between the 15th and 18th centuries.31

The 13th century Masjid Fakhr al-Din, ca. 1927-1929. Image by Khalid Mao Abdulkadir et al. ‘The twin ogival and pyramidal vaulted roof is its distinctive feature.’

Domed mosque at Mwana, Kenya, dated to the 13th-14th century. Image by Thomas H. Wilson

Domed mosque of Diani, Kenya.

The Basheikh Mosque and Minaret, ca. 1910, The Mbaraki Pillar, ca. 1909-1921, Mary Evans Picture Library.

The Jami’ mosque in Mogadishu, Giama Square, ca. 1923. Archivio fotografico Società Geografica Italiana

The Tombs:

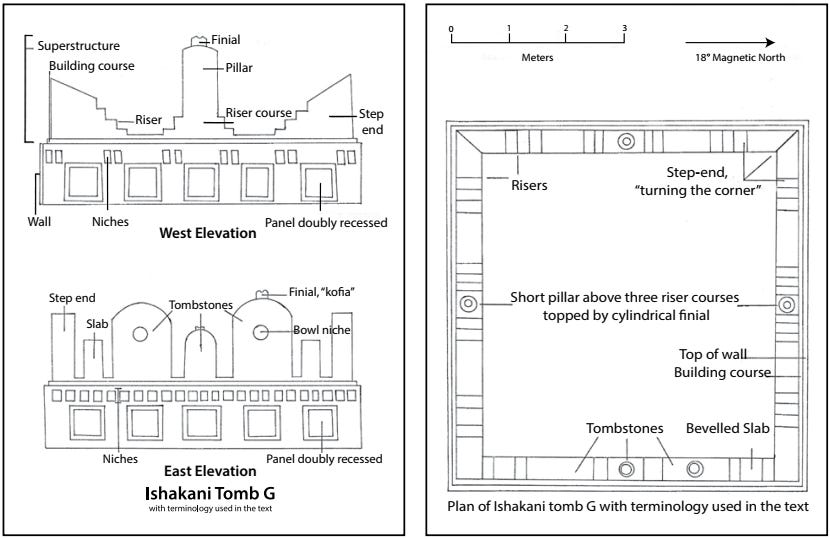

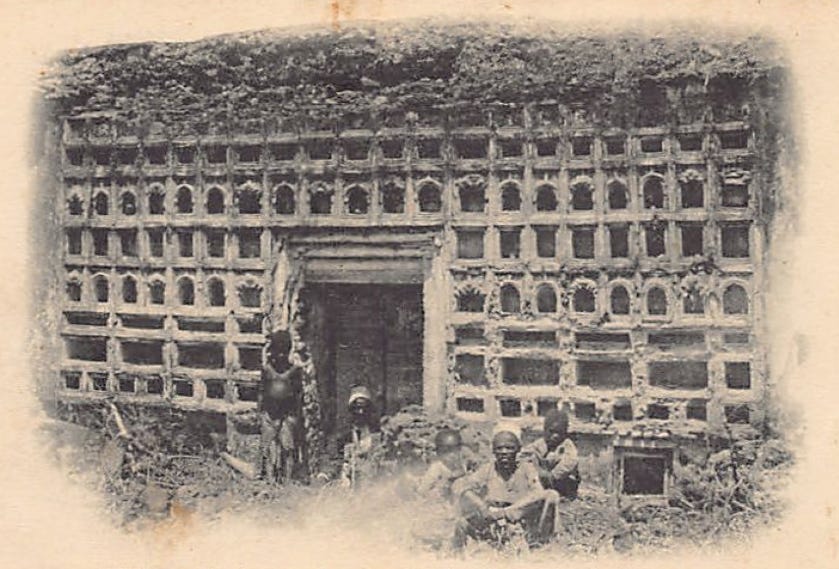

Archaeological evidence suggests that there were two early forms of tomb. The first was the platform tomb, a stepped stone plinth that rested over the grave pit. At the top is a triangular ridge covered in plaster with Koranic verses scratched into the surface. This type is found at Shanga, Manda, and Kilwa, dated to between the 11th and 13th centuries. The second is a simple enclosure, built up from the ground level, marking out the grave pit. Some have doorways and may be more like family plots with multiple burials. Both types featured inscribed tombstones and inset bowls.32

Shanga cemetery. Image by Thomas H. Wilson

Pillar tombs first appear in the 13th century in the Lamu archipelago, before spreading to multiple coastal sites by the 14th and 15th centuries. Pillar tombs could contain inscriptions, porcelain bowls, rectangular niches, and carvings on the pillar itself, which could be round, square, polygonal, or fluted. Alongside these were domed tombs contemporary with the introduction of vaulted mosques in the 15th century. Swahili tomb architecture declined during the 16th century, but was later revived in the late 18th century as part of a wider reassertion of local identity in the face of Omani expansionism.33

Step-end tomb, Kiunga, Kenya. Image by Neville Chittick

Tombs at Ishakani, Kenya. Images by Thomas H. Wilson

Elevation and plan of a tomb at Ishakani, Kenya. Image by Thomas H. Wilson

Domed tomb at Ungwana, Kenya. Image by Thomas H. Wilson.

Cemetery near Mombasa, Kenya, ca. 1907. MAA, Cambridge

Tombs in Kunduchi, Tanzania.

Swahili architecture in the medieval period

The classical style of Swahili architecture remained in vogue long after the end of the Middle Ages, and throughout the Portuguese irruption as new Swahili centres emerged at Pate, Lamu, and Nzwani during the 17th to 18th centuries, and Zanzibar in the 19th century. Remains of houses in Pate and Nzwani dating to the 18th century display many of the standard architectural features of the classical era.34

interior of a ruined house in Nzwani (Anjouan), Comoros.

Flat-bottomed and decorative blind niches, in the palace of Mutsamudu, Nzwani. Image by S. Pradines and Olivier Onezime

Vidaka (wall niches) in the House in Eastern Pate. Image by Thomas H. Wilson

Many of the oldest surviving Swahili coast merchant houses were built during this period, especially in the 18th and 19th centuries, and would later form the prototype of modern Swahili architecture, which dominates the cityscape in the old towns of Lamu, Mombasa, and Zanzibar.

While some modern Swahili houses incorporate or attempt to mimic pre-colonial construction styles, complete with internal courtyards, narrow passageways, and carved doors, the majority of the structures utilize modern building materials and styles, with wider windows, verandahs on upper floors, and more angular forms which point to their colonial influences.35

An 1884 photograph of the Hinawy House (as it is known today) in Mombasa before it was reconstructed by Tharia Toban (see below) with a verandah and balcony added in the 1890s. Image and caption by Prita Meier

(left) Toban House (the Hinawy House) with an intricate cast-iron verandah on the second floor, circa 1880s. Mombasa (right) The store of a textile merchant with an elaborate second-floor verandah. ca. 1908, Mombasa. Image and caption by Prita Meier

Today, the old architecture of the East African waterfront is a symbol of past glories, when the Swahili coast people actively participated in complex networks of exchange across vast distances.

The Swahili merchant house, having lost its function as a symbol of patrician identity, has acquired new significance as an important tourist attraction, enabling the preservation of this unique pre-colonial African architectural style that once dominated the built environment of the East African coastline.

Sections of Old Town Mombasa and other streets, ca. 1927-1940, Mary Evans Picture Library.

Zanzibar, Tanzania. ca. 1936 -Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek

The beachfront of Modern Lamu, Kenya.

Between 1853 and 1895, at least seven kingdoms in southern Africa sent embassies to the court of Queen Victoria, five of which successfully met with the monarch and were treated as official envoys of what were then independent states.

The perspectives of these South African explorers and the consequences of their diplomatic negotiations are the subject of my latest Patreon article:

Please subscribe to read more about it here and support this newsletter:

maps by Edward Pollard

The Archaeology of Tanzanian Coastal Landscapes in the 6th to 15th Centuries AD: The Middle Iron Age of the Region by Edward John David Pollard pg 43-45, Ceramics and the Early Swahili: Deconstructing the Early Tana Tradition by Jeffrey Fleisher and Stephanie Wynne-Jones

Unguja Ukwu on Zanzibar by A. Juma, pg 16

Further Archaeological Research on Mafia Island by Felix Chami, pg 212-213

Unguja Ukwu on Zanzibar by A. Juma, pg 148, The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones and Adria LaViolette, pg 169-172

Urban Chronology at a Human Scale on the Coast of East Africa in the 1st Millennium a.d by Stephanie Wynne-Jones et al

Unguja Ukwu on Zanzibar by A. Juma, pg 82-83

The Social Landscape of a Mercantile Society by Mark Horton, John Middleton pg 48-71, Early Swahili Mosques: The Role of Ibadi and Ismaili Communities, Ninth to Twelfth Centuries by Stephane Pradines pg 216-218.

The Swahili: The Social Landscape of a Mercantile Society by Mark Horton, John Middleton pg 47, 177

Unguja Ukwu on Zanzibar by A. Juma, pg 152-153

The early Swahili trade village of Tumbe, Pemba Island, Tanzania, AD 600–950 by Jeffrey Fleisher & Adria LaViolette

The Archaeology of Tanzanian Coastal Landscapes in the 6th to 15th Centuries AD: The Middle Iron Age of the Region by Edward John David Pollard pg 65-66

The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones and Adria LaViolette, pg 215

The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones and Adria LaViolette, pg 216, Primitive Islam and architecture in East Africa by M Horton, pg 110

Primitive Islam and architecture in East Africa by M Horton, pg 105-108, The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones and Adria LaViolette, pg 217-218,

Early Swahili Mosques: The Role of Ibadi and Ismaili Communities, Ninth to Twelfth Centuries by Stephane Pradines, pg 222-223

The Archaeology of Tanzanian Coastal Landscapes in the 6th to 15th Centuries AD: The Middle Iron Age of the Region by Edward John David Pollard, pg 50-51

Coral architectures and Indian ocean Maritime resources by Stephane Pradines, Early Swahili Mosques: The Role of Ibadi and Ismaili Communities, Ninth to Twelfth Centuries by Stephane Pradines, pg 223-225, 234. Shanga: The Archaeology of a Muslim Trading Community on the Coast of East Africa by Mark Chatwin Horton, pg 417-418

Early Swahili Mosques: The Role of Ibadi and Ismaili Communities, Ninth to Twelfth Centuries by Stephane Pradines, pg 219-221

The Swahili: The Social Landscape of a Mercantile Society by Mark Horton, John Middleton pg 49-50. The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones and Adria LaViolette, pg 233)

The Chronology of Kilwa Kisiwani, AD 800–1500 by Mark Horton et al.

The Chronology of Kilwa Kisiwani, AD 800–1500 by Mark Horton et al., pg 21-22, The Swahili: The Social Landscape of a Mercantile Society by Mark Horton, John Middleton pg 62-64

A Material Culture: Consumption and Materiality on the Coast of Precolonial East Africa, by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, pg 69

The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones and Adria LaViolette, pg 510-511, The Archaeology of Tanzanian Coastal Landscapes in the 6th to 15th Centuries AD: The Middle Iron Age of the Region by Edward John David Pollard, pg 66

The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones and Adria LaViolette, pg pg 501

The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones and Adria LaViolette, pg 502-506

Eighteenth century Lamu weddings by L Donley Reid, pg 1-5, The public life of the Swahili stonehouse, 14th–15th centuries AD by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, pg 761-763

Early Swahili Mosques: The Role of Ibadi and Ismaili Communities, Ninth to Twelfth Centuries by Stephane Pradines, pg 223, 236-237

The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones and Adria LaViolette, pg 489, In the Name of Shirāz: The stone mosques of the East African coast reconsidered

The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones and Adria LaViolette, pg 490-491, 493-495

The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones and Adria LaViolette, 492, 495-496)

The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones and Adria LaViolette, pg 496

The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones and Adria LaViolette, pg 497-498, Pillar Tombs and the City: Creating a Sense of Shared Identity in Swahili Urban Space by Monika Baumanova

The Ujumbe of Mutsamudu, an Eighteenth-Century Swahili Stone House in the Comoros Stéphane Pradines and Olivier Onezime

Swahili Port cities: The Architecture of Elsewhere by Prita Meier, pg 57-62

Outstanding work as always. Kudos!!

Thanks for excellent article filled with details and pictures! I have been to the ruins on Mafia Island, which I thought were very impressive, but I didn't know about the ruins further south. Thank you so much for the pictures!