Guns and Spears: a military history of the Zulu kingdom.

Popular history of Africa before the colonial era often divides the continent’s military systems into two broad categories —the relatively modern armies along the Atlantic coast which used firearms, versus the 'traditional' armies in the interior that fought with arrows and spears. And it was the latter in particular, whose chivalrous soldiers armed with antiquated weapons, are imagined to have quickly succumbed to colonial invasion.

Nowhere is this imagery more prevalent than in mainstream perceptions of the Anglo-Zulu war of 1879. Descriptions of Zulu armies armed with short spears and shields, bravely rushing over open ground in the face of heavy fire in an attempt to get to grips with the redcoats, has come to dominate our understanding of colonial warfare. It casts this 'traditional' African army as an atavistic warrior people in their twilight, whose supposed failure to innovate doomed them to their seemingly inevitable fall.

Like all simplified narratives, the popular division between traditional and modern military systems is more apparent than real. The guns of Queen Njinga’s army in Matamba (Angola) were just as effective at defeating the Portuguese colonial armies in the 17th century1, as the arrows of Chagamire Dombo were at crushing the colonialists forces in Mutapa (Zimbabwe).2 And as the the 19th century colonial expansionism intensified, the Zulu armies defeated the British in the field on no less than three occasions.

This article explores the history of Zulu military innovations within their local context in south-east Africa, and the overlooked role of firearms in Zulu warfare.

Map of southern Africa in the early 19th century showing the Zulu kingdom.

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more on African history and keep this blog free for all:

Genesis of the Zulu military system: Southern African armies and weapons from the 16th to the 18th century.

The Zulu kingdom emerged in the early 19th century, growing from a minor chiefdom in Mthethwa confederation, to become the most powerful state in south-east Africa. Expanding through conquest, diplomacy and patronage, the kingdom subsumed several smaller states over a large territory measuring about 156,000 sqkm.

The Zulu state owed much of its expansion to its formidable army during the reign of King Shaka (1812-1828), the kingdom's first independent ruler. The Zulu military developed during Shaka's reign utilized a distinctive form of organization, fighting formations and weapons, that were popularized in later literature about colonial warfare in Africa. Chief among these was the regiment system, and the short-spears known as assegai that were utilized in the famous cow-horn formation of close-combat fighting.3

Like most historical traditions which attribute important cultural innovations to the kingdom's founder, these innovations are thought to have been introduced by king Shaka. However, they all predate the reign of the famous Zulu king, and most of them were fairly common among the neighboring states of south-east Africa. Among such states was the Thuli chiefdom, which, during its expansion south of the Thukela River in the late 18th century, employed the short-spear in close combat. Another tradition relating the the Mtehthwa king Dingiswayo also attributes the use of short stabbing spears to his armies, replacing the throwing spear. The line of transmition then follows both of these innovations from Dingiswayo's son to a then prince Shaka, when the Zulu were still under Mtehthwa's suzerainty.4

The short spear often associated with king Shaka was itself a relatively ancient weapon among the polities of south-east Africa. The earliest descriptions of armies in the region from the mid 16th century include mentions of warriors armed with wooden pikes "and some assegais [spears] with iron points.” These descriptions came from shipwrecked Portuguese sailors whose desperation attimes drove them to cannibalism against the Africans who they found near the coast, and thus invited severe retaliation from the African armies. One such incident of cannibalism by the Portuguese crew near Delagoa bay5 (Maputo Bay) resulted in the shipwrecked crew being attacked by an African army “throwing so many assegais [azagayas, or spears] that the air was darkened by a cloud of them, though they seemed afterwards to be as well provided with them as before.” A similar attack is described by another shipwrecked crew in 1622 whose camp was showered with more than 530 assegais and countless wooden spears.6

The type of assegais used in the region where the Zulu kingdom would later emerge would have been fairly similar to the ones associated with Shaka. One account from 1799 mentions that the armies in Delagoa bay region were "armed with a small spear" which they "throw with great exactness thirty or forty yards". The account also describes their armies' war dress, their large shields and their form of organization with guard units for the King. These were all popularized in later accounts of the Zulu army but were doubtlessly part of the broader military systems of the region. 7

The above fragmentary accounts of military systems in south-east Africa indicate that traditions attributing the introduction/invention of the Zulu’s military formations and weapons to Shaka were attimes more symbolic than historical, although they would be greatly improved upon by the Zulu.

Development and innovation of the Zulu military system from Shaka to Dingane: Assegais and Firearms.

According to the Zulu traditions recorded in the late 19th century, Shaka trained his warriors to advance rapidly in tight formations and engage hand-to-hand, battering the enemy with larger war-shields, then skewering their foes with the short spear. Shaka's favorite attack formation was an encircling movement known as the impondo zankomo (beast's horns), in which the the isifuba, or chest, advanced towards the enemy’s front, while two flanking parties, called izimpondo, or horns, surrounded either side.8

There were many types of assegais in 19th century Zululand, including the isijula, the larger iklwa and unhlekwane, the izinhlendhla (barbed assegais), and the unhlekwana (broad-bladed assegai) among others. Assegais were manufactured by a number of specialized smiths, who enjoyed a position of some status, and were made on the orders of, and delivered to, the king, who would distribute them as he saw fit. The assegai transcended its narrow military applications as it epitomized political power and social unity of the state. It also played an important part in wedding and doctoring ceremonies, as well as in hunting. It acquired an outsized position in Zulu warfare and concepts of honor that emphasized close combat battle.9

The Zulu army originally formed during the reign of Shaka's predecessor, Senzangakhona (d. 1812), was an age-based regimental force that developed out of pre-existing region-based forces called amaButho. These regiments were instructed to build a regional barracks (Ikhanda) where they would undergo training. The barracks served as a locus for royal authority as temporary residences of the King and a means to centralize power. Shaka greatly expanded this regimental system, enrolling about 15 regiments, with the estimated size of his army being around 14,000 in the early 19th century, which he sent on campaigns/expeditions (impi) across the region.10

Zulu Soldiers of King Panda's Army, 1847. Library of Congress.

‘Zulu Braves’ in ceremonial battle dress, National Archives UK, late 19th/early 20th century.

the Zulu in ceremonial war dress, early 20th century photo, smithsonian museum

The exact size of the regiment, the location of their barracks and the number of regiments varied under sucessive rulers. When a new regiment was formed, the king appointed officers, or izinduna to command it. These were part of the state officials, specifically chosen by the king to fulfil particular roles within the administrative system. Regiments consisted of companies (amaviyo) under the command of appointed officers, which together formed larger divisions (izigaba) also commanded by appointed officers, who were in turn under the senior commanders of the Zulu army.11

The creation of the different regiments was largely determined by the King, while the military training of the cadets who joined them was mostly an informal process. Some of the regiments dating back to Shaka's time were still present at the time of the Anglo-Zulu war, others had been created during the intervening period, while others were absorbed. The regiments were distinguished by their war dress and shields, although these two changed with time. These regiments were armed with both the short spear and large shield, but they also carried guns —an often overlooked weapon in Zulu historiography. One particular regiment associated with this weapon in the Anglo-Zulu war were the abaQulusi, a group which eventually came to consider themselves to be directly responsible to the King.12

The Zulu had been exposed to firearms early during kingdom's creation in the 1820s. Shaka was keenly intrested in the guns carried by the first European visitors to his court and acquired musketry contigents to bolster his army.13 He also sent Zulu spies to the cape colony and intended to send envoys to England inorder to learn how to manufacture guns locally. His sucessors, Dingane (r. 1828-1840) and Mpande (r. 1840-1872), acquired several guns from the European traders as a form of tribute in exchange for allowing them to operate within the kingdom.14

<<the journey from Zululand to England wouldn't have been an unusual undertaking, since African explorers —including from southern Africa— had been travelling to western Europe since the 17th century. >>

While firearms acquired by the Zulu during Dingane’s reign were not extensively used in battle before the war between the Boers and the Zulu between 1837-1840, they quickly became part of the diverse array of weaponry used by his army. The Zulu had innovated their fighting since Shaka’s day, bringing back the javelin (isiJula) for throwing at longer distances, as well as knobkerries (a type of mace or club). Dingane also armed some of his soldiers with firearms, the majority of which seem to have been captured from the Boers after some Zulu victories. The Zulu army of Dingane also rarely fought using the cow-horn formation but frequently took advantage of the terrain to create more dispersed formations, often seeking to surprise the enemy and prevent them from making any effective defense.15

The Zulu developed an extensive vocabulary reflecting their familiarity with the new technology, with atleast 10 different words for types of firearm, each with its own history and origin, as well as a description of its use. These included a five-foot long gun called the ibala, a large barreled gun known as the imbobiyana, a double barreled shotgun known as the umakalana which was reserved for the elite, two other shotguns known as isinqwana and ifili (the first of which was used in close range fighting), and the "elephant gun" known as the idhelebe which unlike the rest of the other guns was acquired from the Boers rather than the Portuguese. Other guns include the iginanda, umhlabakude, igodhla, and isiBamu.16

The bulk of firearms in the kingdom arrived from the British colony of Natal and the Portuguese station at Delagoa Bay, especially during the reign of Cetshwayo (r. 1872-1879/1884). The king utilized the services of a European trader named John Dunn whose agents transshipped the weapons from the Cape and Natal to Delagoa Bay and into Zululand. In the 1860s and 70s, the exchange price of a good quality double-barrel muzzle loader dropped from 4 cows or £20 to just one, while an Enfield rifle that was standard issue for the British military in the 1850s cost even less. This trade was often prohibited by the British in the Cape and Natal who feared the growing strength of the Zulu, but the "illegal" sales of guns carried on until the Portuguese were eventually forced to prohibit the trade in 1878.17

Portuguese accounts indicate that between 1875 and 1877, 20,000 guns, including 500 breech-loaders, and 10,000 barrels of gunpowder were imported annually, the greater proportion of which went to the Zulu kingdom. This indicates a total estimate of 45,000 guns including 1,125 breech loaders and 22,500 barrels of gun powder. Another account from 1878 mentions the arrival of 400 Zulu traders at Delagoa who purchased 2,000 breech loaders. Zulu smiths learned how to make gunpowder under the supervision of the king's armorer, Somopho kaZikhala with one cache containing about 1,100 lb of gunpowder in 178 barrels.18

Flintlock Brown Bess musket bearing the Tower mark, typical of the firearms carried by the Zulu in 1879, Zululand Historical Museum, Ondini

(left) illustration of a Zulu attack formation at Isandlwana, with shields, guns and short spears . (right) 'Followers of the Zulu king, Cetshwayo, including his brother, Dabulamanzi, all carrying long rifles. photo taken in 1879 after the war, National Army Museum

Firearms and Assegais in the Zulu victory over the British.

By the time of the Anglo-Zulu war in 1878, the majority of Zulu fighters were equipped with firearms, although they were unevenly distributed, with some of the military elites purchasing the best guns while the rest of the army had older models or hardly any. King Cetshwayo became aware of this when a routine inspection of members of one of the regiments revealed that they had few guns, and he ordered them to purchase guns from John Dunn. While the number of guns was fairly adequate, ammunition and training presented a challenge as they often had to use improvised bullets, and not many of them were drilled in good marksmanship.19

From the Zulu army's perspective however, the kingdom was at its strongest despite some of the constraints. The British estimated King Cetshwayo’s army at a maximum strength of 34 regiments of which 7 weren't active service, thus giving an estimate of 41,900, although this was likely an over-stated. The force gathered at the start of the Anglo-Zulu War, which probably numbered about 25,000 men, was the largest concentration of troops in Zulu history.20 With about as many guns as the Asante army (in Ghana) when they faced off with the British in 1874.

The perception of the Zulu army by their British enemies often changed depending on prevailing imperial objectives and the little information about the Zulu which their frontier spies had collected. One dispatch in November 1878 noted that the “introduction of firearms” wrought “great changes, both in movements and dress”, upon the “ordinary customs of the Zulu army”. Another dispatch by a British officer in January 1879 observed that Zulu armies “are neither more bloodthirsty in disposition nor more powerful in frame than the other tribes of the Coast region”. The slew of seemingly contradictory dispatches increased close to the eve of the battle, with another officer noting that the Zulu army's "method of marching, attack formation, remains the same as before the introduction of fire arms.".21

The above assessments, and the other first-hand accounts provided below must all be treated with caution given the context in which they were made and the audience for which they were intended.

Throughout January 1879, a low-intensity war raged in the northwestern marches of the kingdom, culminating with a major clash at Hlobane. One account of the first battle of Hlobane on 21st January details the abaQulusi regiment's careful charges to minimize losses and their extensive use of firearms. The officer noted that his force was "engaged with about 1,000 Zulus, the larger proportion of whom had guns, many very good ones; they appeared under regular command, and in fixed bodies. The most noticeable part of their tactics is that every man after firing a shot drops as if dead, and remains motionless for nearly a minute. In case of a night attack an interval of time should be allowed before a return shot is fired at a flash". He also noted that they fired guns when the British advanced but utilized the assegai when the enemy was in retreat.22

While the first engagement at Hlobane ended in a British victory, this minor defeat for the Zulu was reversed the next day once they engaged with the bulk of the colonial forces at Isandlwana. Instead of a wild charge down the hill and across the wide plain, the Zulu regiments filed down the gullies of the escarpment and made a series of short dashes from one ridge to another toward the British position, only rising up to charge at the enemy once they were within a very short distance of the camp. The battle of Isandlwana, on 22 January 1879, was an imperial catastrophe, and a monumental victory for the Zulu, resulting in the loss of over 1,300 soldiers, including 52 officers and 739 Colonial and British men, 67 white non-commissioned officers and more than 471 of the Natal Native Contingent.23

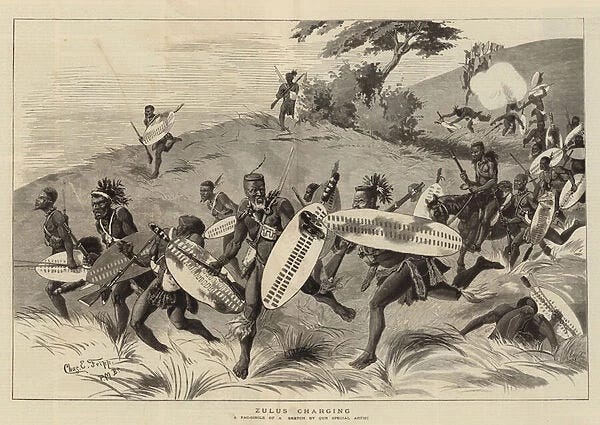

a fairly accurate Illustration of a Zulu charge, made by Charles E. Fripp in 1879, showing the complete array of weapons.

Firearms in Zulu military strategy.

The role of firearms in the Zulu victory was understated in later accounts for reasons related to the changing purposes to which depictions of the Zulu were put by the British over the course of the war. The dispatch by the colonial commissioner who had ordered the invasion, Henry Frere, suggested that the defeat resulted from the British having faced “10 or even 20 times their own force, and [having been] exposed to the rush of such enormous bodies of active athletes, perfectly reckless of their own losses, and armed with the short stabbing assegai". Another dispatch noted that "every Zulu is a soldier, and as a nation they are brave, fond of fighting, and full of confidence in themselves … There can be no doubt of the warlike character of the Zulu race. Their present military organization would also show that they are capable of submitting to a severe discipline." 24

Yet there are reports of the same battle which accurately describe the Zulu advance using firearms, before the last charge with assegais. One officer notes that the Zulu army advanced carefully, noting that "it was a matter of much difficulty to do really good execution among the ranks of the enemy, owing to the fact that with marvelous ingenuity they kept themselves scattered as they came along", another observed that "From rock and bush on the heights above started scores of men; some with rifles, others with shields and assegais. Gradually their main body; an immense column opened out in splendid order upon each rank and firmly encircled the camp”.25 This contradicts the notion that the Zulu were simply throwing hordes of spearmen into the battle, something that would've been extremely costly given the kingdom's relatively low population (of just 100-150,000 subjects26) and very limited manpower compared to what the British could muster from the neighboring colonies.

This tactic was also witnessed at a later battle at Gingindlovu, on 2 April. The officer observed that once the Zulu were within 800 yards of the British camp, "they began to open fire. In spite of the excitement of the moment we could not but admire the perfect manner in which these Zulus skirmished. A knot of five or six would rise and dart through the long grass, dodging from side to side with heads down, rifles and shields kept low and out of sight. They would then suddenly sink into the long grass, and nothing but puffs of curling smoke would show their whereabouts."27

A later interview with Zulu war veterans in 1882 summarizes their preferred tactics as thus; "They went through various manoeuvres for my entertainment, showing me how they made the charges which proved so fatal to our troops. They would rush forward about fifty yards, and imitating the sound of a volley, drop flat amidst the grass; then when firing was supposed to have slackened, up they sprung, and assegai and shield in hand charged like lightning upon the imaginary foe, shouting ‘Usutu’." Its likely that Henry Frere's account of charging athletes with assegais was an oversimplification of this final advance, when the initial slow advance with firearms gave way to a swift charge with assegais.28

The choice to utilize both firearms and assegais was influenced as much by cultural significance of the assegai as it was by the relatively low quality of the firearms and marksmanship. Zulu guns were of diverse origins, including German, British and American muskets, but some were old models having been made in 1835, in contrast to the British's Martini-Henry which was made just 8 years before the war. While these Zulu guns had been relatively effective in the earlier wars, they constrained the range at which Zulu marksmen could accurately fire their weapons and increase enemy causalities. The Zulu captured 1000 Martini-Henrys and 500,000 rounds of ammunition at Isandlwana which they put to good use in later battle of Hlobane which they won on 28th March 1879 and as well as the defeat at Khambula the next day. As one British officer at Khambula observed, the Zulu he encountered were "good shots" who "understood the use of the Martini-Henry rifles taken at Isandlwana". However, the captured weapons weren't sufficient for the whole army to use in later engagements and were distributed asymmetrically among the soldiers.29

King Cetshwayo had hoped his victory at Isandlwana would persuade the British to reconsider their policies, but it only provoked a bitter backlash, as more British reinforcements poured into the region. Isandlwana had been a costly victory, a type of fighting which the Zulu army had not before experienced, and the terrible consequences of the horrific casualties they suffered became more apparent with each new battle, with the successive defeats at Gingindlovu and Ulundi eventually breaking the army.30

The King Cetshwayo in exile, London, 1882.

Conclusion.

The Zulu army was a product of centuries in developments in the military systems of south-east Africa. The Zulu’s amaButho system and fighting formations were well-adapted to the South African environment in which they emerged, and were continuously innovated in the face of new enemy forces and with the introduction of new weapons, including guns.

While the Zulu did not kill most of their enemy with firearms, references to the Zulu’s mode of attack suggest that their tactical integration of firearms reflected a greater familiarity and skill in their use than is often acknowledged. The Zulu frequently demonstrated adaptive skills in their tactical deployment of a diverse array of weapons and fighting styles that defy simplistic notions of traditional military organization.

The gun-wielding regiments that quietly crept behind the hill of Isandlawana, with their shields concealed behind the bushes, were nothing like the charging hordes of imperial adventure that blindly rushed into open fields to be mowed down by bullets. The Zulu army was a highly innovative force, acutely aware of the advantages of modern weaponry, the need for tactical flexibility in warfare, and the limits of the kingdom’s resources. In this regard, the Zulu were a modern pre-colonial African army par excellence.

Isandlwana and graves of the fallen of 1879.

In the 16th century, Africans arrived on the shores of Japan, many of them originally came from south-east Africa and eastern Africa, and had been living in India. read more about this African discovery of Japan here:

nn

The Creation of the Zulu Kingdom, 1815–1828 By Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 76

The Creation of the Zulu Kingdom, 1815–1828 By Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 27, 31, 61-62)

post-publication correction, this encounter actually took place 65 miles northeast of the Mthatha River, which is 450 miles south of Maputo Bay.

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 62, 81)

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 145-146)

The Anatomy of the Zulu Army by Ian Knight pg 32, 192-209)

A Cultural History of Firearms in the Age of Empire pg 144, 147)

The Creation of the Zulu Kingdom, 1815–1828 By Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 35-41, The Anatomy of the Zulu Army by Ian Knight pg 33-34, 51-54)

The Anatomy of the Zulu Army by Ian Knight pg 60, 64, 82)

The Anatomy of the Zulu Army by Ian Knight pg 61, 84, 105-107, A Cultural History of Firearms in the Age of Empire by Karen Jones pg 146,)

A Note on Firearms in the Zulu Kingdom with Special Reference to the Anglo-Zulu War, by J. J. Guy pg 557-558

The Creation of the Zulu Kingdom, 1815–1828 By Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 152, 166, 243, 256, Companion to the Anglo-Zulu War By Ian Knight pg 183)

The Zulu-Boer War 1837–1840 By Michał Leśniewski pg 97-100

The James Stuart Archive of Recorded Oral Evidence Relating to the History of the Zulu and Neighbouring Peoples pg 63, Zulu–English Dictionary Alfred T. Bryant pg 20

Kingdom in crisis By John Laband pg 62-63, A Note on Firearms in the Zulu Kingdom with Special Reference to the Anglo-Zulu War, by J. J. Guy pg 560

A Cultural History of Firearms in the Age of Empire by Karen Jones pg 131, Kingdom in crisis By John Laband pg 63)

Companion to the Anglo-Zulu War By Ian Knight pg 184

The Anatomy of the Zulu Army by Ian Knight pg 35)

A Cultural History of Firearms in the Age of Empire by by Karen Jones pg 132)

A Cultural History of Firearms in the Age of Empire by by Karen Jones pg 136-137, The Anatomy of the Zulu Army by Ian Knight pg 210)

Companion to the Anglo-Zulu War By Ian Knight pg 118

A Cultural History of Firearms in the Age of Empire by by Karen Jones pg 132)

Witnesses at Isandlwana by Neil Thornton, Michael Denigan, A Cultural History of Firearms in the Age of Empire by by Karen Jones pg 139)

The Zulu-Boer War 1837–1840 By Michał Leśniewski pg 97

The Anatomy of the Zulu Army by Ian Knight pg 212)

The Anatomy of the Zulu Army by Ian Knight pg 213)

Kingdom in crisis By John Laband pg 64-65, Companion to the Anglo-Zulu War By Ian Knight pg 185)

The Anatomy of the Zulu Army by Ian Knight pg pg 42)

I'm really happy to have found your substack. Thank you. Talking of the use of firearms ... I think the book by one of my great (n) grandfathers might be an interesting read. "My adventures in Swaziland" by Owen Roe O'Neil. It's very much written in the times by someone who describes himself as a Boer (he was of Irish origin) but his proximity to Queen Labotsibeni and her son Bhuno (spelt Buno in his book). My own understanding is that he (my ancestor) was basically gun-running. He was also able to write about the experience through his eyes and at close quarters. If you are interested, the book is in the library of congress here - https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/gdc/gdclccn/21/01/86/06/21018606/21018606.pdf

Excellent article.