Historic industries of pre-colonial Africa and the glassworkers of ancient Nubia

Significant strides have been made over the last decades in the study of the pre-colonial industries of Africa, especially regarding their emergence and the scale of production.

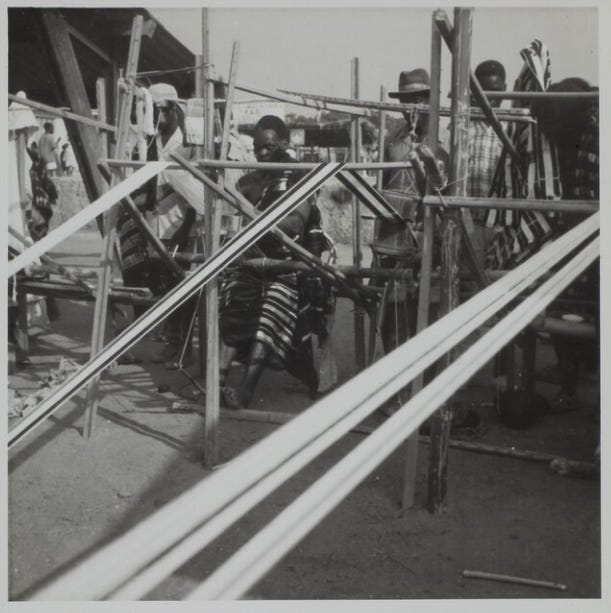

The ubiquitous finds of spindle whorls in virtually all major archaeological sites across the continent are often considered direct evidence of the thriving textile industries which are extensively described in historical accounts. Pre-colonial societies developed a diverse range of looms and sophisticated weaving techniques using cotton, raffia, and other natural fibers to manufacture large quantities of cloth, some of which are found in museum collections worldwide.

African cloth exports to European coastal traders during the early 17th century indicate that domestic textile production was large enough to supply the regional markets. An estimated 38,000 meters of cloth was purchased by Dutch traders in the city of Benin in 1644-46, while Portuguese traders bought about 100,000 meters of cloth in 1611 from the kingdom of Kongo.

By the 19th century, cloth production in the city of Kano reached proto-industrial levels, employing an estimated 20,000 dyers in a city of 100,000. The city's wealthiest merchants created complex manufacturing enterprises dealing with the import and export trade across long distances by controlling much of the production process.

weavers at work on traditional double-heddle looms with pulley wheels and foot peddles ca. 1930-1950, Côte d'Ivoire. Quai Branly

dyeing textiles with indigo in Kano, ca. 1938. Quai Branly.

Embroidered Cotton and silk tunic. Ethiopia, ca. 1877, British Museum.

Besides textiles, the working of iron, copper, and gold is arguably the best known and studied among pre-colonial Africa's industries and pyro technologies. From the earliest evidence of the processing of iron in the furnaces of Oboui and Gbatoro in Cameroon and Central Africa around c. 2200–1965 BCE, African societies have exploited the three metals simultaneously, using a wide variety of furnaces to fashion many luxury and utilitarian metal artifacts

Recent estimates of the quantities of iron slag and the number of furnaces found at some of these sites give some indication of the scale of this production. Specialist centers of iron production have been recorded in the Fiko region of Mali (300,000 m3 of slag), at Bassar in Togo (82,000 m3), and at Korsimoro, Burkina Faso (60,000 metric tonnes), and the Cameroon Grasslands (137,000 tonnes). In the middle Senegal River Valley, 41,325 single-use furnace bases were counted in an 80-km section alone.1

Such production was often expanded during wartime. In the 1880s, the Wasulu ruler Samori Ture had entire villages of blacksmiths who manufactured modern rifles, musketballs and gunpowder. An estimated 300-400 smiths worked full-time to make about 200-300 rounds of ammunition a day and 12 rifles a week using local sources of metal. By 1893, Samori had amassed over 6,000 rifles, which he used in his battles with the French until 1898.2

The French commander Louis Archinard, who wrote an informative article about the Mande blacksmiths of Samory, examined some of Samory's guns and found them to have very accurate breech mechanisms. In the 20th century, Mande smiths were still able to make rifles, pistols, and ammunition entirely using local ores and methods of metalworking.3

Natural draft furnaces in the Seno plain below Segue, Burkina Faso, 1957, Quai Branly. Earthen smelting furnaces in Ouahigouya, near the capital of Yatenga kingdom, Burkina Faso, 1911, Quai Branly.

Iron smelting at Oumalokho near the border of Mali & Cote d’ivoire, illustration by Louis Binger, ca. 1892.

Flintlock pistol from Dahomey, Benin, ca. 1892, Quai Branly. Rifle from Bornu, Nigeria, ca. 1905. American Museum of Natural History

Other industries that have been the subject of significant study include construction (such as the mason guilds of Hausaland and Djenne); Shipbuilding (especially on the East African coast); intensive agriculture (such as in the Bendair region of Somalia), and glassworking in the medieval city of Ile-Ife.

Glassworking was one of the most sophisticated technologies invented in the pre-industrial world, and glass objects were some of the most valuable trade items of the ancient world. While previous studies of glass in Africa focused on its trade and consumption, the discovery of a primary glass production site of Igbo Olukun, an industrial quarter of Ile-Ife, provided the first direct evidence for an independent invention of glass in Africa.

Archaeological excavations conducted at Igbo Olokun recovered more than 20,000 glass beads, glass waste, and glass-encrusted crucibles dated to the 11th-15th centuries. Glass manufactured at Ife has been found in multiple sites across West Africa; as far as Kumbi Saleh, the capital of medieval Ghana in Mauritania, and Tie, the capital of medieval Kanem in Chad.4

Glass studs in metal surround from Iwinrin Grove, and a glass sculpture of a snail. Ile-Ife, Nigeria. ca. 11th-15th century. images by Suzanne Blier

Besides Ife, some of the most significant evidence for an African glass industry has been found in the cities of ancient and medieval Nubia, with discoveries of glass workshops and glass waste in the sites of Hamadab, Meroe, Debeira, and Old Dongola.

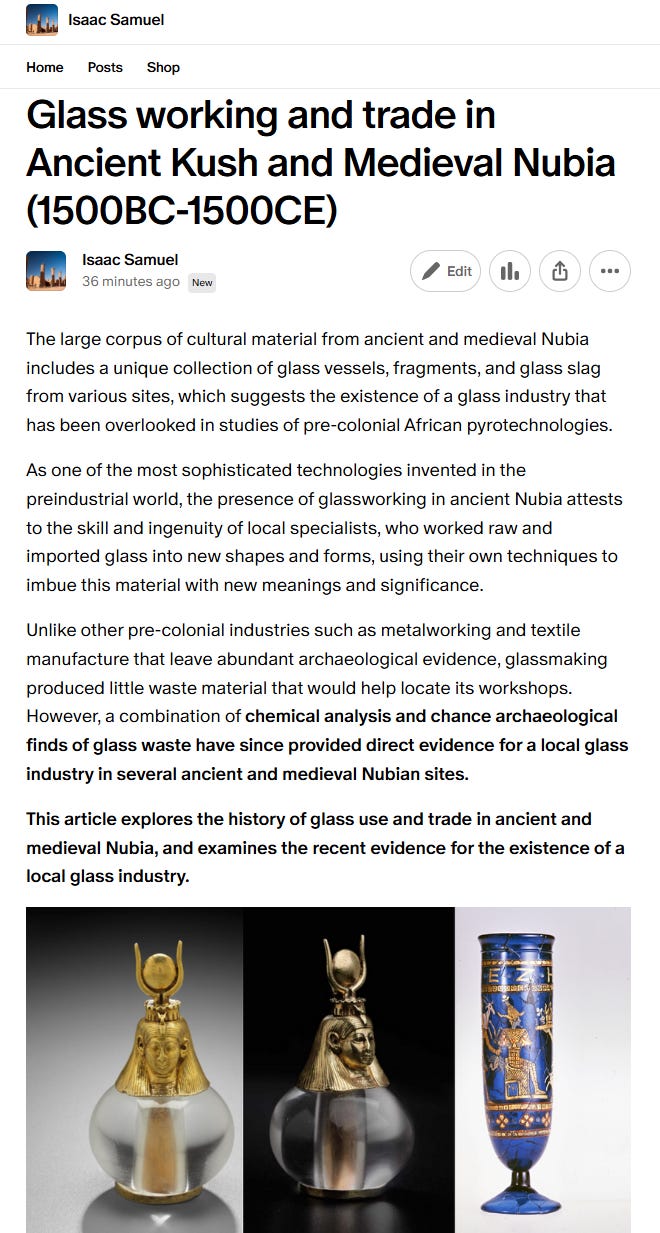

Glass was considered a luxury material in Nubia and appears extensively in the archaeological record of elite settlement sites and grave goods across the region. Its use was largely decorative, for jewelry, as a surface adornment of walls, furniture, and windows, and for a wide variety of vessels that were used as containers for wine, perfumes, and other precious liquids.

While the glass objects found in ancient and medieval Nubia were initially assumed to have been imports, new research shows that some were made by local craftsmen, whose skill and ingenuity were well attested in other mediums like gold, faience, bronze, and iron.

The history of glassworking and trade in ancient and medieval Nubia is the subject of my latest Patreon article,

Please subscribe to read more about it here:

Opaque green glass. Hieroglyphic inscription on one face; relief eye on other. Napatan Period, reign of Piankhy (Piye) 743–712 B.C. el-Kurru, Ku. 51 (tomb of an unidentified queen of Piankhy). Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

A Global Perspective on the Pyrotechnologies of Sub-Saharan Africa by D Killick pg 72)

Wars of Imperial Conquest in Africa by Bruce Vandervort pg 132-133, UNESCO General History of Africa, Volume VII pg 123

The Mande Blacksmiths: Knowledge, Power, and Art in West Africa By Patrick R. McNaughton pg 35-37

The Ile-Ife glass bead series: classification, chaîne opératoire and the ‘glass bead roads’ in West African archaeology by Abidemi Babatunde Babalola, Chemical analysis of glass beads from Igbo Olokun by AB Babalola, Ile-Ife, and Igbo Olokun in the history of glass in West Africa by AB Babalola et. al

This is amazing!!! I had no idea we manufactured pistols and gunpowder! Thank you for your work in decolonizing and enlightening us on our continent.

Wow thank you so much for shutting down the myth that pre-Colonial Africans produced nothing. This is incredible information!