Acemoglu in Kongo: a critique of 'Why Nations Fail' and its wilful ignorance of African history.

There aren’t many Africans on the list of Nobel laureates, nor does research on African societies show up in the selection committees of Stockholm. It was therefore a refreshing change when the trio of American economists; Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson, whose work includes research on pre-colonial and modern African societies, won the 2024 Nobel Prize in economics.

The trio has published several articles which argue that the type of institutions established by European colonialists resulted in the poorer parts of the world before the 1500s becoming some of the richest economies of today; while transforming some of the more prosperous parts of the non-European world of the 1500s into the poorest economies today. Their central argument is that colonies with “inclusive institutions” protected the property rights of European settlers while those with “extractive institutions” prevented investment and the adoption of technology while extracting rents from the indigenous populations.1

While their work was mostly concerned with explaining why the wealthier regions of pre-Columbian America and South Asia became poorer than adjacent regions in North America and Australia after European colonialism,2 two of the authors; Acemoglu and Robinson, would later include research on pre-colonial and modern African societies in their 2012 book titled: 'How Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty', using the kingdom of Kongo as their primary case study for how pre-existing extractive institutions were reinforced by European colonialism.

Acemoglu and Robinson have faced heavy criticism from scholars who believe their work oversimplifies complex historical and economic processes.

A 2008 article by the historian Gareth Austin for example points out that their data wasn't dependent on the inclusion of African countries, suggesting that the evidence from Africa contradicts their general hypothesis and is inapplicable to the continent. He questioned the quality of the evidence they used which was often anecdotal rather than qualitative, he challenged their exaggeration of the influence of Europeans in pre-colonial African history which is unsupported by modern African historiography and minimizes African agency. He concludes with a compelling critique that Acemoglu and Robinson ‘compress history’ in their attempt to create an all-embracing theory3.

One of the most widely shared critiques of Acemoglu and Robinson’s book is a recent opinion piece in the Financial Times by the columnist Brendan Greeley, who noted that while Acemoglu and Robinson are right to see the importance of institutions, they are unable to understand the political and cultural forces that drive institutions. "Acemoglu and Robinson read a book called American Slavery, American Freedom, used the bits about American freedom and tossed the bits about American slavery. The new economic institutionalists treat work on institutions by a celebrated historian not as a coherent argument, but as a source of anecdotes." Brendan advises young economists to stop by the history department, grab a book, and "read the whole thing"4.

This essay examines Acemoglu and Robinson's analysis of pre-colonial African societies, with a particular focus on the kingdom of Kongo, showing how the two authors only studied Kongo's history to extract evidence that supported their pre-conceived hypothesis but disregarded and misrepresented all evidence which contradicted it.

Map showing the 17th century kingdoms of Africa’s Atlantic coast including the kingdom of Kongo.5

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Contradictions in the sources?

In ‘Why Nations Fail’, Acemoglu and Robinson begin their analysis of pre-colonial African societies by claiming that none of them had developed writing (except Ethiopia and Somalia), the plow, or the wheel, despite contacts with European and Asian merchants. They explain Africans’ refusal to adopt these technologies using the example of the kingdom of Kongo, arguing that the Portuguese introduced these three technologies to Kongo but they were rejected, except firearms.

Acemoglu and Robinson argue that the people of Kongo rejected these technologies because state taxes were high and arbitrary; that the people’s very existence was threatened by slavery so they moved away from markets; and that the kings, whose power was absolutist, had no incentive to adopt the plow because exporting slaves was more profitable.6

The book’s footnotes reveal the sources of these claims to be Anne Hilton's 'The Kingdom of Kongo' (published in 1985) and John Thornton's 'The Kingdom of Kongo: Civil War and Transition, 1641–1718' (published in 1983). Hilton and Thornton are both specialists on the history of the kingdom of Kongo, especially the latter who has published eight books and over twenty articles about the history of Kongo, Africa, and the Atlantic world.7

John Thornton's works, such as the well-cited and aptly titled 'Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World', often explore themes that highlight African agency in its people's interactions with Europeans. Using the exceptionally plentiful documentary record about the kingdom of Kongo,8 Thornton's work has dispelled myths about the supposed weakness of the pre-colonial African states and economies.9 He is also a vocal critic of 'dependency theorists' who argue that European merchants had an overwhelming influence on pre-colonial African societies, all of which makes him a rather surprising choice for Acemoglu and Robinson, whose entire argument rests on this exact premise.10

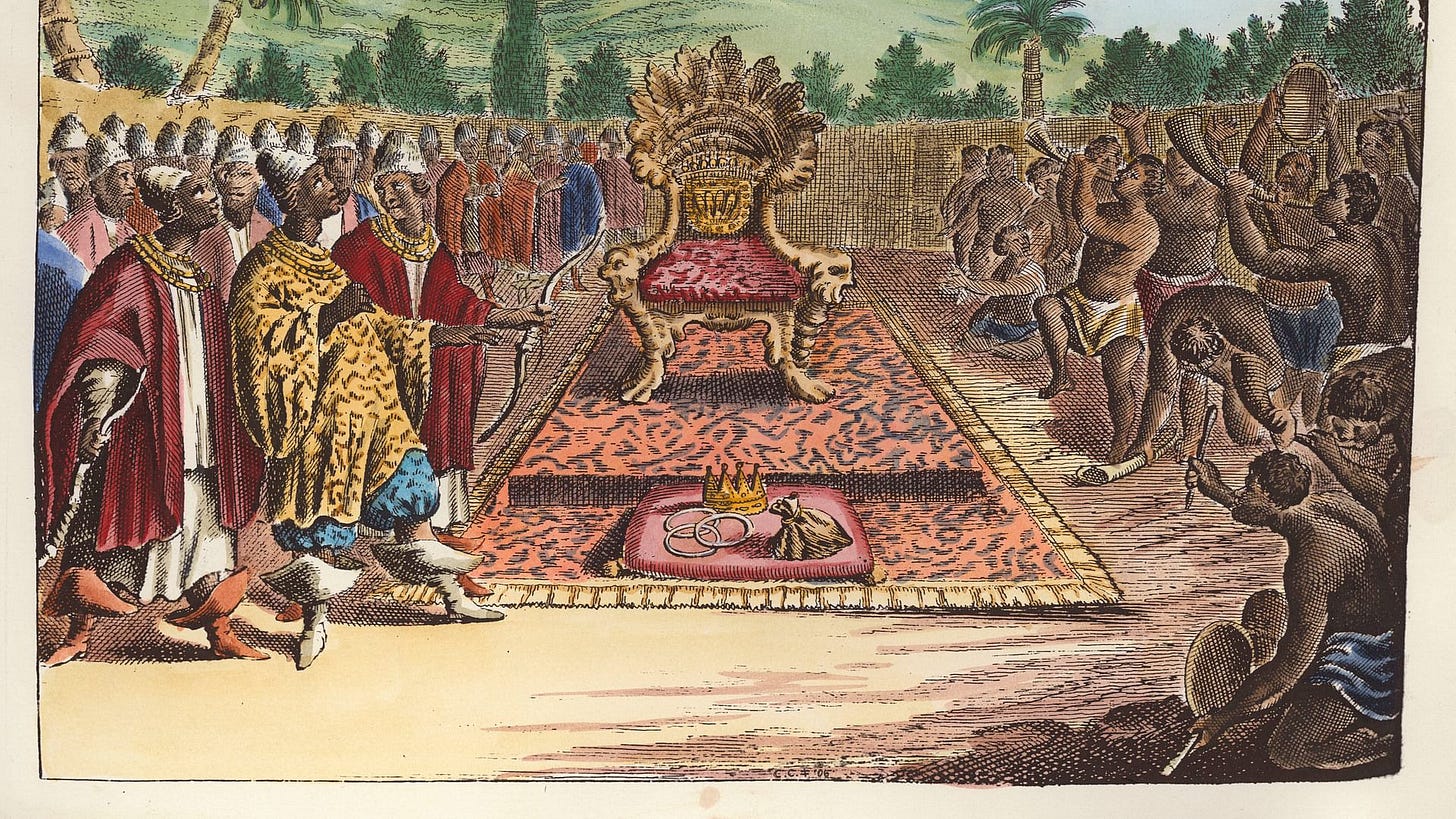

Engraving in Olfer Dapper’s description of Africa, 1668, showing a Dutch delegation at the court of the King of Kongo, in 1641. This was the cover for Thornton’s ‘Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World’. The context of this engraving is about how Kongo exploited Portuguese and Dutch rivalries during the 30-years war.

Rivaling Europe: Agriculture and Textile production in pre-colonial Kongo.

Thornton is one of the few Africanists who have focused on the question of technology and industry in pre-colonial Africa, which Acemoglu and Robinson are preoccupied with. He warns his peers against "using a simple piece of technology like the presence or absence of the hoe, as a proxy measure for productivity". He prefers to rely on contemporary accounts, such as those written by European visitors to; Kongo (Giovanni Francesco da Roma in 1645); the Gold Coast (Pieter de Marees and Wilhelm Johann Mulle in 1668); Senegal (Alvise da Mosto in 1455), and several others who observed that African farmers were more productive than European farmers of that period where those authors came from.11

For the kingdom of Kongo in particular, Giovanni Francesco da Roma observed that "They do not plow, but only scratch up the soil with a little hoe to cover the seed. In return for this little effort, they reap most abundantly"12. Quantitative records for yields per hectare from colonial Angola corroborate these observations. Agricultural yields in Angola’s central highlands declined drastically after the imposition of the colonial government; from 1,600 kg/ha in 1887 to just 400 kg/ha in the 1920s, ironically, AFTER the plow was introduced by the Portuguese.13

A similar observation of the efficiency of Africa's "simple" technology was demonstrated in the textile industry of Kongo, whose eastern province of Momboares exported 100,000 meters of cloth in 1611 to Luanda, according to a Portuguese customs official. Using fixed looms and village-based subsistence labour, Momboares, which was only a small part of central Africa's great ‘textile belt', had a production capacity that rivaled that of Holland's province of Leiden, which was one of Europe's leading cloth producers.14

The quality of Kongo's luxury cloth was also frequently compared to Italian luxury cloth —itself the best in Europe — including by Italian visitors like Antonio Zucchelli in 1705. The cloth produced by Kongo’s textile industry served as currency (called mabongo/ libongo), it was used in burial shrouds and as wall hangings, making it the main store of wealth for the peasants. Most of the exported cloth was sold along the coast by European traders whose profits from the cloth trade were four times greater than from the slave trade according to figures provided by Hilton.15 Some of the Kongo textiles were also exported to Europe to make cushion covers, and the surviving examples leave little doubt regarding their high quality.

Kongo luxury cloth: cushion cover, 17th-18th century, Polo Museale del Lazio, Museo Preistorico Etnografico Luigi Pigorini Roma.

18th century engraving showing the funeral process of Andris Poucouta, a Mafouk of Cabinda on the Loango coast, made by Louis de Grandpre. The coffin that carried him was at least 20 feet long by 14 feet high and 8 feet thick, the whole was transported by a wheeled wagon pulled by at least 500 people over a road built for the purpose.

Kongo's textile production was also not exceptional, similar quantities of cloth export are noted by 17th-century Dutch traders in the neighboring kingdom of Loango, which exported about 80,000 meters of cloth.16 The West African kingdom of Benin was also a major textile producer whose quality of cloth was also compared to that found in Leiden and Harlem by the Dutch traders, who purchased 38,000 meters of it in 1644-46, which they mentioned was less than what the English had bought from Benin.17 17th-century Portuguese traders on the East African coast praised the quality of cloth produced on the island of Pate (in Kenya), which they used in their ivory trade with the mainland, routinely seized in battle, and some settlers bought it for themselves.18

The relatively high productivity of African agriculture and cloth production contradicts the dependency theories proposed by Acemoglu and Robinson, which are mostly based on conjecture rather than historical evidence. It also strengthens the argument that Africans dictated the terms of their exchanges with coastal merchants. Thornton thus cautions against relying on simple theoretical arguments rather than available documentary sources, observing that "all too often comparisons between Africa and Europe in this time period both understate the strength of the African economy and overstate the modernity and productivity of the European economy."19

Misrepresenting pre-colonial Africa’s political systems: Acemoglu and Robinson’s myth of absolutism in Kongo.

The above outline is relevant in examining Acemoglu and Robinson’s erroneous description of Kongo's political organization as absolutist.

Neither Hilton nor Thornton claim that the King of Kongo had unconstrained power, they instead emphasize that a council of officials elected him, and they in fact frequently refer to the king's enthronement as an 'election'. According to Hilton and Thornton, these electors were part of an elite who constituted a corporate group that 'owned' the state's land, with the King only filling a representative role and acting as a senior executive whose office could appoint officials and collect income on their behalf, but was expected to redistribute this income.

As stated by Hilton; "wars could not be declared, officials named or deprived, roads opened or closed without the consent of the council." She also describes "several institutions" that "balance the power of the king at the centre", while Thornton provides other examples of similar councils in other parts of Africa which demonstrate that Kongo's political structure wasn't unique20.

Acemoglu and Robinson's description of the absolutist authority of the king of Kongo is therefore contradicted by their own sources.

This is also evident in their claim that Kongo's taxes were arbitrary and heavy, which was apparently taken from Thornton's account of the kingdom during the mid-17th century in the years preceding the Civil War. Thornton was describing the kingdom of Kongo during its ‘late period’ when its kings were centralizing their power at the expense of the council, and one of the many ways they did this was to expand their sources of income, especially in the capital.

However, Thornton also notes that "The head tax of two mabongo in Nsoyo was in any case not a crushing burden ; it is safe to say that even poor families would have been able to raise it, since they would have needed anywhere from 80 to 120 mabongo to marry." [this 80 to 120 mabongo cloth-currency was given to the priest who officiated the wedding, not to the state]. Thornton adds that during this period, many peasants were engaged in specialized labour like textile production because of taxes, among other reasons, which contradicts Acemoglu and Robinson's claims that taxes forced the peasants to flee from the markets and curtailed production.21

Slavery in Africa and early-modern Europe.

Having wilfully misrepresented their sources on Kongo's political structure and taxation, it’s unsurprising that Acemoglu and Robinson misunderstand the nature and dynamics of slavery and slave trade in the kingdom of Kongo. While they claim that Kongo's subjects were at risk of enslavement by their Kings, both Hilton and Thornton repeatedly stress that for most of the kingdom’s history, slaves exported from Kongo were often bought from further inland or acquired as war captives.22

Thornton's other articles on the Kongo-Portugal wars, also highlight two major episodes during the 1580s and the 1620s where Kongo's kings demanded that Portugal repatriate its illegally enslaved citizens from Brazil, with more than a thousand baKongo being successfully tracked down and returned to Kongo after these requests.23 This, and other evidence such as the numerous letters of King Afonso Nzinga (r. 1509-1542) concerning the regulation of slavery in Kongo, prove that there were laws against the enslavement of 'free-born' citizens in the kingdom and that these laws were strictly enforced,24 contrary to Acemoglu and Robinson's claims.

Acemoglu and Robinson's reductive analysis of the dynamics of slavery and 'free labour' in Kongo is also demonstrated in other sections of the book, where they argue that the rise of feudalism and serfdom in medieval Europe led to the decline of slavery, and that similar processes occurred in medieval Ethiopia with the gult system of land tenure extracting the agricultural surpluses produced by serfs rather than slaves, which the authors claim was exceptional in sub-Saharan Africa where only slave institutions prevailed.25

However, this binary between slave labour and free labour (serfs and wage labourers) was very uncommon in world history and was mostly confined to a handful of countries in Western Europe and the Americas specifically during the early modern period. Scholars of internal slavery in late medieval Europe such as Hannah Barker, argue that no such binary existed in the Latin world, where more than nine different social and legal groups of ‘unfreedom’ existed, which were all translated as ‘slaves’ in English literature.26

She discusses the varying theories proposed by different groups of scholars for the apparent decline of slavery in post-Roman Europe, which she says is contradicted by the prevalence and importance of slave trade to the societies of the wealthy cities of southern Europe such as Venice and Genoa where thousands of slaves from northern, eastern and central Europe were sold to Ottoman merchants during the late middle ages.27

Figures for European slavery in the succeeding period from 1500-1700 are provided by the historian Dariusz Kołodziejczyk, who writes that the "slave population imported into Ottoman lands from Poland-Lithuania, Muscovy and Circassia, amounted to over 10,000 a year in the period 1500-1650." He estimates that total slave exports from this region alone amounted to about 2,000,000 between 1500-1700, compared to 1,800,000 for the Atlantic slave trade from the entire coastline of West Africa and Central Africa*.28 [*Note that Kongo's main coastal port of Mpinda exported a total of just under 3,100 slaves for the entire period between 1526–1641 according to David Eltis29]

The dynamics of slavery and slave trade across most of Europe were therefore not too different from those in Africa, at least, as far as feudalism is thought to have led to their decline. It’s for this reason that some forms of slavery persisted in medieval and early modern Ethiopia despite its gult system of land tenure, just as slavery persisted in those European regions that captured and sold European slaves to the Ottomans. Slavery was after all, not incompatible with feudalism as Acemoglu and Robinson believe.

Breaking the myth of Ethiopian exceptionalism: Land tenure and Literacy in pre-colonial Sub-Saharan Africa.

The theme of Ethiopia's supposed exceptionalism in "sub-Saharan" Africa that is touted by Acemoglu and Robinson and many Western writers, has little basis in African historiography. In truth, the gult system that allowed land to be alienated, inherited or sold by private owners wasn't only found in Ethiopia but was similar to the land tenure of systems of medieval Nubia, the Sudanic kingdoms of Darfur and Funj, the west African empires of Bornu, Sokoto and Masina, as well as in the city of Brava30 on the southern coast of Somalia.

There are many written accounts about land tenure from at least four of these societies (Nubia, Darfur, Sokoto, Bornu) concerning the state's administration of land tenure and rent, land sale documents, and land grants, some of which have been studied by historians such as Donald Crummey in his 2005 book; ‘Land, Literacy and the State in Sudanic Africa’. According to the land documents of the pre-colonial kingdom of Darfur analyzed by the historian R. S. O'Fahey, a comprehensive listing of a grantees’ rights in his estate is given on one of the documents as such: “...as an allodial estate, with full rights of possession and his confirmed property... namely rights of cultivation, causing to be cultivated, sale, donation, purchase, demolition and clearance.”31

land charter of Nur al-Din, a nobleman from the zaghawa group originally issued by Darfur king Abd al-Rahman in 1801 and renewed in 1803.32

Acemoglu and Robinson’s claims on the apparent rarity of writing in Kongo and in sub-Saharan Africa also reveal their unfamiliarity with the history of writing in Africa, and in world history. The claim that Africans didn’t develop writing (save for Ethiopia and Somalia) is contradicted by the overwhelming evidence of manuscript cultures across the continent, the studies of which were laboriously cataloged for the ‘Arabic Literature of Africa’ project, led by the historian John Hunwick, which now boasts five volumes.

Any serious scholar of African history is expected to at least have basic knowledge of the inscriptions of ancient Kush and medieval Nubia, and the manuscript collections of Timbuktu and Bornu, Sokoto and the East African coast, because its these documents which provide the primary sources for reconstructing the history of Africa. They should also be familiar with the scholarly traditions of the Wangara of medieval Mali and Songhai who are credited with establishing numerous intellectual centers across West Africa, the Fulbe scholars who played a central role in the revolution movements of 19th-century west-Africa, and the Jabarti scholarly diaspora from Zeila in northern Somalia which appears in the biographies of Mamluk Egypt.

Its unfortunate that the authors of such a popular book on pre-colonial Africa overlooked this crucial information and refused to do their homework, despite dedicating entire sections providing seemingly authoritative explanations on why Africans apparently lacked writing or didn't use it even when they had access to it.

Acemoglu and Robinson’s wilful ignorance of basic information on African history was doubtlessly influenced by their need to buttress the claim that Kongo's “extractive institutions” militated against the spread of writing despite Kongo's elites adopting the Latin script.

Acemoglu and Robinson expound on this apparent rarity of African writing in another section of the book about Somalia's lack of centralized polities, which they surmised was because its clan institutions rejected technologies such as writing. They explain Somalia’s apparent lack of writing using the example of the kingdom of Taqali, a small polity in Sudan, where writing in Arabic was apparently only used by royals because the rest of the subjects feared it would be used to control their land and impose heavy taxes on them.33

[Its a strange choice to use this relatively obscure kingdom in a country like Sudan that boasts over 4,000 years of recorded history]

However, none of Acemoglu and Robinson’s speculations regarding writing in pre-colonial Somalia and Kongo are supported by historical evidence. Their claim that the "king of Kongo made no attempt to spread literacy to the great mass of the population" is contradicted by evidence presented by Hilton and Thornton that spreading literacy across the kingdom was exactly what King Nzinga Afonso strove to accomplish with the establishment of schools not just in the capital but also in the provinces, with later kings continuing in this tradition, such that literacy became central to administration and to Kongo's international diplomacy.34

Writing was not confined to the elites but was also spread to the rest of the population who held literacy in high regard, especially in the religious sphere where it was considered necessary by the lay members of Kongo's church. As one 17th-century account describing Kongo's Christian commoners noted: “Nearly all of them learn how to read so as to know how to recite the Divine Office; they would sell all they have to buy a manuscript or a book.” Another account from the 1650s, which also describes Kongo’s commoners also mentions that they “have a great desire to learn and they are very ambitious to appear literate; in the processions those who have learnt all the letters of the alphabet stick a piece of paper in the form of a card on their forehead so as to be recognized as a student.”35

These positive descriptions of Kongo’s literacy by European visitors of the 17th century should be placed in the context of early-modern Europe, whose literacy rates were relatively low compared to the present day, just like in every region of the world before the Industrial Revolution. A mere 30% of English men* were able to read and write in the 1640s —which was the highest literacy rate in Europe— compared to countries like Spain where as recently as 1841, only 17% of adult men* could read and write36. [*note that these figures are drastically reduced if women and children are included]

Its therefore unsurprising that descriptions of Kongo's literary culture by European visitors in the 16th and 17th century were mostly positive because literacy rates in Kongo were not too dissimilar to literacy rates in their home countries.

European descriptions of literacy rates in other parts of pre-colonial Africa also indicate that they considered the African societies which they encountered to be just as if not more literate than those in their home countries.

For example, Baron Roger, the governor of St. Louis, wrote that there were in Senegal “more negroes who could read and write in Arabic in 1828 than French peasants who could read and write French.” The English trader Francis Moore who also visited the Sene-gambia region in 1730-1735 wrote that in “every Kingdom and Country on each side of the River of Gambia,” Pulaar-speakers were “generally more learned in the Arabick, than the people of Europe are in Latin." The explorer René Caillié, who visited Timbuktu in 1828, also observed that “all the negroes of Timbuktu are able to read the Qur’an and even know it by heart.”37

The spread of literacy in Africa followed several different trajectories. While literacy in Kongo was a top to down affair which spread from the royals to the nobility and commoners (similar to Kush, medieval Nubia, Aksum, the kingdom of Bamum, and the Vai of Liberia), literacy in the rest of Africa was spread by itinerant merchant scholars who created education networks that connected different centers of learning, and spearheaded reform movements that challenged the authority of the rulers. Most of these scholars weren't dependent on royal patronage, as the scholars of Timbuktu, Djenne, Ngazargamu, and Salaga were quite eager to prove by challenging Mansa Musa's Arab expatriates,38 the repression of Askiya Ishaq (r. 1539-1549),39 and the injustices caused by the rulers of Bornu and Gonja.40

A similar dynamic between the scholarly communities and the political elite existed in Somalia. Contrary to the claims of Acemoglu and Robinson, Somalia was home to several states including the empires of Adal and Ajuran, the sultanates of Mogadishu, Geledi, Majerteen, all of which are amply described in the same sources that Acemoglu and Robinson included in their footnotes, such as I. M. Lewis' ‘A Modern History of the Somali’. (4th ed, 2002, pgs 45-54).

Lewis' book was mostly concerned with the mainland of southern Somalia and thus made little mention of the scholarly communities of the coastal cities like Barawa and Zeila where a vibrant literary tradition flourished since the middle ages and spread into the interior41. He nevertheless published a ground-breaking study of the religious communities of pre-colonial Somalia titled 'Saints and Somalis: Popular Islam in a Clan-based Society' (1998), in which he explores the significance of influential sufi orders among whom were prominent scholars like Sheikh Abdirahman Ahmad az-Zayla'i (d. 1882) from Zeila whose was influential across northern Somalia, and Sheikh Uways al-Barawi (d. 1909), a prolific author from Barawa whose influence extended across East Africa.

Acemoglu and Robinson's section on Somali history is unusually fixated on the Osmanya alphabet ('Somali script') that was invented by Osman Yusuf Kenadid well into the colonial period in 1920, despite it not being the writing system of pre-colonial Somalia, nor an exceptional invention.

There are many other scripts from ‘sub-saharan’ Africa from the pre-colonial era besides the Ge'ez script of Ethiopia and Eritrea, these include the Meroitic script (ca. 150 BC), the Nsibidi script (11th-18th century), the Vai script (ca. 1830), and Njoya's script (1897). Dozens of scripts were also invented during the colonial and post-independence periods, with at least twenty-two being identified in West Africa alone.

West African script invention, ca. 1832-2011. Map by Piers Kelly42.

With a few exceptions, most of the colonial-era scripts were invented for nationalist reasons, but their spread was restricted because pre-existing scripts like Arabic and Ajami were well suited for the literary traditions of Africa, in the same way that the English and most Europeans didn't need to invent a new script after they had adopted the Latin script.

Acemoglu and Robinson were either unaware that writing was fairly widespread in pre-colonial Africa, or more likely, they considered the Ge'ez and Osmanya scripts as the only legitimate forms of African writing systems while dismissing the Arabic and Ajami scripts possibly because they were adopted. However, this raises important questions regarding England's lack of an independently invented script, and whether Acemoglu and Robinson think this aided the emergence of the country's supposedly “inclusive institutions” compared to Italy —where the Latin script and its related writing traditions originated.

The ‘effeminate machine’: On the absence of wheeled transportation in Africa and Europe.

The deficiencies in Acemoglu and Robinson’s comparative analysis of African and European history are best illustrated by their claim that the "Kongolese learned about the wheel" from the Portuguese but refused to adopt it. This is demonstrably false, as neither Hilton nor Thornton mention anything about wheeled technology being introduced to Kongo by the Portuguese. Hilton specifically mentions that the Portuguese introduced hammocks (basically just fancy beds lifted by people), during the 16th century.43

Method of travel in the Kingdom of Kongo, taken from Giulio Ferrario's ‘Il costume antico e moderno’ (1843)

The fact that Europeans introduced this curious ‘technology’ instead of wheeled vehicles, should come as no surprise to any reader familiar with the history of wheeled transportation in Europe and the rest of the old world. The historian Richard W. Bulliet published two of the most cited books on this topic; ‘The Camel and the Wheel’ (1975) and ‘The Wheel: Inventions and Reinventions’ (2016).

Bulliet argues that wheeled vehicles were widely adopted across the ancient world, mostly in the form of war chariots, before they were gradually displaced by the mounted warrior in battle around the 8th century BC, and by the camel in trade in the early centuries of the common era, leaving only limited use of wagons in farmwork for short hauls.44

The wheel thus disappeared across much of the old world during the Middle Ages, including in Europe, where royals, nobles, and ordinary merchants used pack animals, and where "Kings and knights considered all kinds of carriages as effeminate machines, and scorned to be seen within them . . . As late as the reign of Francis I [r. 1515–1547], there were only three coaches in Paris."45

However, cultural attitudes towards wheeled carriages and coaches eventually shifted during the 16th to 17th century. This wasn't because coaches were suddenly considered a more functional means of travel than the horse, but simply because they were later seen as more prestigious [and they dropped the ‘effeminate’ label]. The use of coaches remained restricted to the royals and elites, mostly for ceremonial functions, because ordinary transport using such vehicles was heavily constrained by the poor quality of the roads which were only improved in the 18th and 19th centuries just as rail transport was being invented.46

Bulliet also provides other examples across the rest of the world, such as from Persia, where an English visitor in 1883 noted “the roads then becoming impracticable to wheelcarriages, we were obliged to perform the rest of the journey on horseback in Persian saddles. . . . I saw no wheel-carriages of any kind in Persia” and Japan in 1870s, where two European visitors noted; "Everything is transported from and into the interior by horses and bullocks. I have seen no wheeled vehicles except the [hand-pulled] jinrikisha and there are very few of these."47

Bulliet’s analysis of the wheel in world history is generally supported by other scholars of medieval and early-modern travel in Europe including; Julian Munby on the transition from carriages used by royal women in the late Middle Ages to coaches of elite men in the early modern period,48 Erik Eckermann on the disappearance of wheeled carriages in post-Roman Europe until the 16th century,49 And Peter Roger Edwards's on the coach's re-introduction in mid-16th century England and its slow spread among the nobility because it was considered “effeminate”.50

Despite the modern obsession with wheeled transport, the wheel’s insignificance in the early-modern period had long been recognized by professional economic historians like William T. Jackman as early as 1916, in his book ‘The Development of Transportation in Modern England, where he notes that in the 18th century England, “Contemporary evidence points very strongly to the conclusion that by far the larger proportion of the carrying was done by pack-horse. Long trains of these faithful animals, furnished with a great variety of equipment … wended their way along the narrow roads of the time, and provided the chief means by which the exchange of commodities could be carried on.”51

Its relevant to note that both road building and wheel technology were attested in a number of African societies during antiquity and the early modern period. Wheel technology appears extensively in the military, transport, and irrigation systems of ancient Kush, while ceremonial carriages and wagons for mobile field pieces also appear in ceremonial and military contexts in the kingdoms of Dahomey and Loango.

In Kongo, the army of its province of Soyo deployed four field pieces mounted on wagons to annihilate the Portuguese army at the battle of Kitombo in 167052 which successfully expelled them from the kingdom for the next two centuries before they would return in 1914 to depose the last king of Kongo, Manuel III.

conclusion: Why Theories Fail.

The historical evidence outlined above undermines Acemoglu and Robinson's central argument on pre-colonial African institutions and their presumptions regarding pre-colonial Africa's apparent lack of efficient technologies. Their theories are inapplicable to Africa primarily because Acemoglu and Robinson fundamentally misunderstand basic aspects of pre-colonial African history, and they at times wilfully misrepresent their own sources in order to support their pre-conceived hypothesis.

Ironically, the authors dedicate a few paragraphs in their book to discrediting Jared Diamond's theories of geographic determinism, only to fall into the same trap of relying on deficient theoretical formulations.

Acemogulu and Robinson therefore follow in the long tradition of Hegelian writers of Africa, whose wilful ignorance of Africa didn’t stop them from writing authoritatively about the continent. It’s very unfortunate that for most readers of this best-selling book, its erroneous description of Kongo and Somalia will be their first and only encounter with pre-colonial African history.

The throne of Kongo. Olfert Dapper, 1668.

The kingdom of Benin was one of the first African societies to adopt the use of firearms in 1514, However, guns contributed very little to Benin’s military systems during the kingdom’s early history before the 18th century. My latest patreon article explores the cultural and military functions of firearms in the kingdom of Benin

please subscribe to read about it here:

Reversal of Fortune: Geography and Institutions in the Making of the Modern World Income Distribution by Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, James A. Robinson, pg 1265-1269.

The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation, by Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, James A. Robinson, Reply to the Revised (May 2006) version of David Albouy’s “The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Investigation of the Settler Mortality Data.” by Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson.

The ‘Reversal of Fortune’ Thesis and the Compression of History: Perspectives from African and Comparative Economic History by Gareth Austin.

Map by J.K.Thornton, taken from; Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400-1800.

Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty By Daron Acemoglu, James A. Robinson pg 58-59, 87-90

Besides the already listed book, Thornton has also published the following;

-Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800 (1998)

-The Kongolese Saint Anthony: Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian Movement, 1684-1706 (1998)

-Warfare in Atlantic Africa, 1500-1800 (1999)

-Central Africans, Atlantic Creoles, and the Foundation of the Americas, 1585-1660 by Linda M. Heywood, John K. Thornton (2007)

-A Cultural History of the Atlantic World, 1250–1820 (2012)

-A History of West Central Africa to 1850 (2020)

-Afonso I Mvemba a Nzinga, King of Kongo: His Life and Correspondence (2023)

The correspondence of the Kongo kings, 1614-35 : problems of internal written evidence on a Central African kingdom by JK Thornton, New Light on Cavazzi's Seventeenth-Century Description of Kongo by John K. Thornton, The Origins and Early History of the Kingdom of Kongo, c. 1350-1550 by John Thornton.

Early Kongo-Portuguese Relations: A New Interpretation by John Thornton, The Art of War in Angola, 1575-1680 by John K. Thornton, A Re-Interpretation of the Kongo-Portuguese War of 1622 According to New Documentary Evidence by John K. Thornton

Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800 By John Thornton pg 3-6

Precolonial African Industry and the Atlantic Trade, 1500-1800 by John Thornton, pg 6-7 The Historian and the Precolonial African Economy: John Thornton Responds, by John Thornton pg 45-49.

Precolonial African Industry and the Atlantic Trade, 1500-1800 by John Thornton pg 7,

The Growth and Decline of African Agriculture in Central Angola, 1890-1950 by Linda M. Heywood pg 359-366.

Precolonial African Industry and the Atlantic Trade, 1500-1800 by John Thornton pg 11-14.

The Kingdom of Kongo by Anne Hilton pg 77

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 By John K. Thornton pg 13

Benin and the Europeans, 1485-1897 by Alan Frederick Charles Ryder pg 93-98, 129-143.

As Artistry Permits and Custom May Ordain: The Social Fabric of Material Consumption in the Swahili World, Circa 1450-1600 by Jeremy G. Prestholdt pg 12-16

The Historian and the Precolonial African Economy: John Thornton Responds, by John Thornton pg 50

The Kingdom of Kongo by Anne Hilton pg 35-40, The Kingdom of Kongo: Civil War and Transition, 1641-1718 by John Kelly Thornton, pg xi-xii, 43-45, 92, Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800 By John Thornton pg 82-83.

The Kingdom of Kongo: Civil War and Transition, 1641-1718 by John Kelly Thornton, pg 24-25, Acemoglu and Robin’s fixation of the “miserable poverty” of Kongo is actually taken from the description of the villages, and even there, Thornton notes that “this appearance of poverty was an illusion.” (pg 35-36) reflecting different cultural values rather than the sort of economic metrics we use to measure poverty today.

The Kingdom of Kongo by Anne Hilton pg 55, 57-66, 70-73, The Kingdom of Kongo: Civil War and Transition, 1641-1718 by John Kelly Thornton, pg 19-20

A reinterpretation of the Kongo-Portuguese war of 1622 according to new documentary evidence by J.K.Thornton, pg 241-243

Slavery and its Transformation in the Kingdom of Kongo by L.M.Heywood, A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. K. Thornton pg 54-55.

Why Nations Fail : The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson pg 175-178.

That Most Precious Merchandise: The Mediterranean Trade in Black Sea Slaves, 1260-1500 by Hannah Barker pg 14-15. Note that even historians of the early middle ages argue that the terminology for slavery in Europe was very diverse, see; Slavery After Rome, 500-1100 By Alice Rio.

That Most Precious Merchandise: The Mediterranean Trade in Black Sea Slaves, 1260-1500 by Hannah Barker.

Slave hunting and slave redemption as a business enterprise by Dariusz Kołodziejczyk. pg 151-152.

Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade by David Eltis pg 137-138.

Servants of the Sharia: The Civil Register of the Qadis' Court of Brava 1893-1900, Volume I by Alessandra Vianello, Mohamed M. Kassim, pg 32-43, 56-65, 99-151.

Land in Dar Fur: Charters and Related Documents from the Dar Fur Sultanate edited by R. S. O'Fahey, M. I. Abu Salim pg 19.

Land in Dar Fur: Charters and Related Documents from the Dar Fur Sultanate edited by R. S. O'Fahey, M. I. Abu Salim pg 83.

Why Nations Fail : The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson pg 238-243.

The Kingdom of Kongo by Anne Hilton pg 64-65, 79-84, The Kingdom of Kongo: Civil War and Transition, 1641-1718 by John Kelly Thornton, 65-67.

The Kongo Kingdom: The Origins, Dynamics and Cosmopolitan Culture of an African Polity by Koen Bostoen, Inge Brinkman pg 218-224.

Literacy and Education in England 1640-1900 by L Stone pg 100-101, The History of Literacy in Spain by Antonio Viñao Frago pg 578.

Beyond Timbuktu: An Intellectual History of Muslim West Africa By Ousmane Kane pg 7-8.

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Saʿdi's Taʾrīkh Al-Sūdān Down to 1613, and Other Contemporary Documents by John O. Hunwick pg 73-74

African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa By Michael A. Gomez pg 274-275.

examples include the Kunta scholar’s challenge of the Massina state, the village Fuble scholars whose reform movements overthrew the pre-existing kingdoms of Hausaland, Masina and Futa Jallon, and other scholarly communities whose influence on statecraft in precolonial Africa is explored in Nehemia Levtzion and Randall L. Pouwels’ book; ‘The History of Islam in Africa’ (2000).

The scholarly traditions of Barawa have been extensively researched by the historian Alessandra Vianello in his 2018 book; 'Stringing Coral Beads': The Religious Poetry of Brava (c. 1890-1975).

The Invention, Transmission and Evolution of Writing: Insights from the New Scripts of West Africa by Piers Kelly.

The Kingdom of Kongo by Anne Hilton pg 84

The Wheel: inventions and reinventions by Richard W. Bulliet pg 113-132, The camel and the wheel by Richard W. Bulliet pg 16-21

The Wheel: inventions and reinventions by Richard W. Bulliet pg 148

The wheel: inventions and reinventions by Richard W. Bulliet pg 24-25, 96-110, 127- 160

The wheel: inventions and reinventions by Richard W. Bulliet 43-48

The Art, Science, and Technology of Medieval Travel edited by Robert Odell Bork, Andrea Kann, pg 41-53

World History of the Automobile by Erik Eckermann pg 7-10

Horses and the Aristocratic Lifestyle in Early Modern England pg 5,

The Development of Transportation in Modern England, Volume 1 By William T. Jackman, pg 141.

The Art of War in Angola, 1575-1680 by John K. Thornton pg 375, on other examples of field artillery in Kongo, see; Warfare in Atlantic Africa, 1500-1800 By John K. Thornton pg 109-110.

Damn. This is so good. I feel like clapping for you.

I'd be curious what value, if any, there is in their Nobel prize winning research. Everyone is attacking it from every angle lol. Apparently India and China (the two largest countries in the world) are outliers in their plot of "democratic institutions" vs level of development.