The empire of Samori Ture on the eve of colonialism (1870-1898)

a revolution with a contested legacy.

For many centuries, political systems in the societies of the west-African savannah were sustained by a delicate but stable relationship between the influencial merchant class and the ruling nobility. But in the last decades of the 19th century, a revolution among the merchant class overthrew the nobility and created one of the largest empires in the region.

The empire of Samori Ture, which at its height covered an area about the size of France, was the first of its kind in the region between eastern Guinea and northern Ghana. Unlike the old empires of west Africa, Samori's vast state was still in the ascendant when it battled with the colonial armies, and found itself constantly at war both within and outside its borders.

This article explores the history of Samori's Ture's empire from its emergence as a militant revolution to its collpase after the longest anti-colonial wars in French west-Africa.

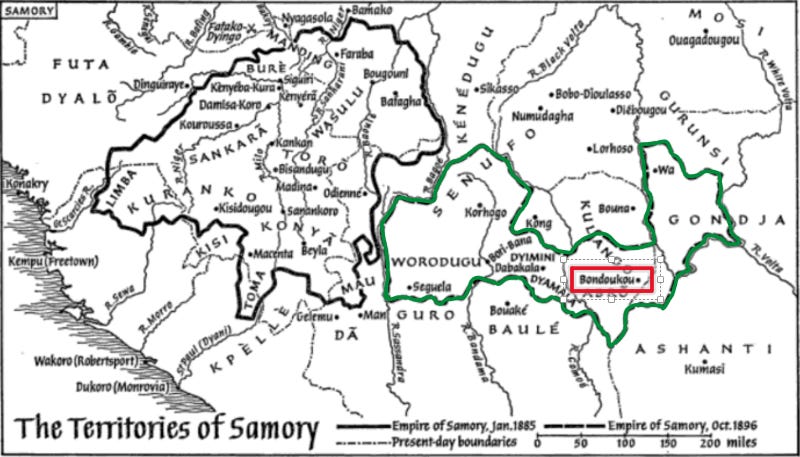

Map of west Africa in the 19th century highlighting the empire of Samori Ture

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Genesis of a merchant revolution.

At the time of Samory's birth in 1830, his Mande-speaking birthplace of Konya (in southern Guinea) was controlled by a symbiotic alliance between the Juula Muslim elites and the traditional nobility which was mostly non-Muslim. The relationship between the Juula families —to whom Samori belonged— and the nobility was symptomatic of the former’s Suwarian tradition, which placed emphasis on pacifist commitment, education and teaching as tools of proselytizing, but rejected conversion through warfare (jihad).1

The Juula of Konya, who were part of west Africa’s wangara diaspora, practiced an Islam that was no different from their co-religionists across west and north Africa: they built mosques for their community and established schools for their kinsmen, but they also advised the nobility in political matters and entered marital alliances with them.

dispersion of the wangara diaspora across west Africa.

But the emerging reform movements of 18th-19th century west Africa inspired new political ideologies which upended the established relationship between Muslim elites and the ruling nobility across the region. These reform movements and ideologies prompted sections of the Juula merchants to agitate for the formation of their own state independent of the traditional dynasties. The Juula reform movements thus produced their own local leaders such as the Juula family of Moli Ule Sise, which defeated the pre-existing dynasties and took over much of Konya by 1835.2

While Samori received some rudiments of Islam in his youth from other Juula teachers, his early career was mostly concerned with long-distance Kola trade, which the Juula merchants excelled at. This trade, often in kola-nut from the southern forest regions, gold from the Bure gold-fields, local cloth and other items, was carried on between the various cities such as Kankan and the Niger valley where horses were bought, and also the coast where firearms and other items were bought. The Juula were thus often pre-occupied with trade than with proselytization, while the political and military hegemony remained with the traditional aristocrats and later with their Sise suzerains.3

Samori initially fought with the Sise armies as a mercenary from 1853-1859, later fighting for a rival Juula dynasty of the Berete in 1861 until 1861 when they expelled him, forcing him to turn to his non-Muslim maternal family, the Kamara, from whom he raised an army that fought with the Sise to defeat the Berete in 1865. Samori later took on the aristocratic title of fama (sword bearer) rather than mansa (ruler) to symbolize his political ambitions independent of the Kamara who had given him his army. He then established his capital at Bisandugu in 1873 and begun a series of campaigns across the region, ostensibly aimed at opening trade routes, and relieving the Juula from the traditional aristocracy.4

Illustration of Samori made after his capture in 1898.

From 1875-1879, Samori's armies had advanced as far as the upper Niger valley (southern Mali) from where he extended his control over Futa Jallon to the west, the Bure goldfields to the north, and the Wasulu region to the east. He then launched two major campaigns that defeated the Sise suzerains of Konya as well as the Kaba dynasty of Kankan between 1880 and 1881. Samori had arrived at the borders of the declining Tukulor empire of Umar Tal's successors which was being taken over by the French forces.5

In February of 1882, the French ordered Samori to withdraw his armies from the trading town of Kenyeran where one of Samori’s defeated foes was hiding, but Samori refused and sacked the town. This led to a surprise attack on his army by a French force which was however forced to retreat after Samori defeated it. Samori's brother, Kémé-Brema, then advanced against the French at Wenyako near Bamako in April, winning a major battle on 2 April, before he lost another in 12 April.

After Samori took control of Falaba in Sierra Leone in 1884, he dispatched emissaries to British-controlled Freetown in the following year, to propose to the governor that he place his country under British protection inorder to stave off the French advance. This initiative failed however, as the French seized Bure in 1885, prompting Samory raise a massive army led by himself, as well as his brothers Kémé-Brema and Masara-Mamadi. Samori's formidable forces forced the French to withdraw from Bure, but later concluded a treaty with them in March 1886. The two parties later signed another treaty in March 1887 that laid down the border between the French colonies and his empire.6

Map of Samori’s first empire in 1885

State and society in Samory’s first empire.

Having come from a non-royal background, Samori's legitimacy initially rested on his military success and personal qualities, before he claimed to be a divinely elected ruler charged with brining order to the region. Lacking the traditional prerogatives of a ruler, Samori chose to institute a theocratic regime led by himself as the Almamy (imam), a title he took on in 1884 after years of study.

The state was administered by a council from the capital (Bisandugu) consisting of top military leaders, and pre-existing chiefs, but later included muslim elites from Kankan. This largely military adminsitration was adopted across the territories from 1879, but differed significantly from place to place as traditional customary law as well as Juula and Islamic law were applied dissimilarly.7

The empire was divided into ten districts under civilian governors, while the two in the center and the capital itself being under Samory's control. The latter were home to the army’s elite corps of about 500 soldiers, which served as the source of most of the officers for the rest of the army. This army was divided into the infantry wing (sofa) which by 1887 of about 30,000 and a cavalry wing of 3,000 in the 1880s. During peacetime, the soldiers and other workers were engaged on plantations, especially around the capital, with some farms reportedly as large as 200sqkm.8

An annual tax was levied on all subjects, following a traditional practice utilized by his predecessors. Samori also instructed his subjects to pay their local Shaykhs an annual stipend, enabling him to establish teachers in each community as auxiliaries to his political agents. The latter exercised surveillance over the population while the former provided primary education for children in Koranic schools. Internal trade rested on the usual commodities of gold, kola, ivory, agricultural produce, and captives, used to purchase horses from the Upper Niger valley region and guns from British sierra leone.9

However, Samori’s experimentation with a theocratic government did not last long, as it ran counter to his Juula subject's symbiotic partnership with their non-Muslim allies. Samori thus faced a major internal conflict when his own father (who had since become non-Muslim) and traditional nobility of the Kamara expressed their opposition to Samori's plans of removing the customary law, and making Islam the state religion. These plans involved the end of the traditional nobility’s festivals (from which they drew their social power) and the designation of Samori's sons as his sucessors instead of his brothers. A comprise was later found where some non-Muslim festivals would continue as long as the nobility joined Samori and his peers in Friday prayers, but tensions would remain and be further exacerbated as Samori recruited more men for his seige of Sikasso.10

the tata (fortification) of Sikasso before and after the two-week French artillery barrage breached it.

ruins of the Fortified residence of Tieba and his sucessor Babemba, in Sikasso, ca. 1897, archives nationales d'outre mer

Fall of Samori’s first empire and the move to the east.

In 1887, Samori mustered all his forces to attack Sikasso, the capital of king Tieba's Kenedugu kingdom. Failing to force Tieba's army out of the fortified city for open battle, Samori besieged the city for over a year. The walls of Sikasso, like most fortified cities across west Africa, enclosed a lot of farmland, which allowed the defenders to withstand a siege much longer than the lightly provisioned attackers could sustain it. So when local rebellions broke out in Wasulu, Samori lifted the siege, and the ensuing wars forced him to end his theocratic experiment.

Samori had afterall recruited non-Muslims in his armies who he used against Muslim strongholds such as Kankan, and in 1883 he defended the non-Muslim Bambara of Bana against the Tukulor armies. So following the mass rebellions of 1888, and Samori's observation of the Muslims' betrayal, he abandoned his northward push to Sikasso, and reverted to his more pragmatic policies for his eastern expansion into the predominatly Muslim societies of Gyaman and Gonja.11

‘Alhabari Samuri daga Mutanen wa’ (the story of samori and the people of wa), an account of Samori’s eastern conquests written by the Wa scholar Ishaq b Uthman in 1922.12

Samori reorganized the army, concluded a treaty with the British in May 1890 which enabled him to buy modern weapons. In April 1891, the French forces attacked Kankan and sacked Bisandugu, but were defeated by Samory at the battle of Dabadugu on 3 September 1891. The French invaded the core regions of Wasulu and managed to defeat Samory in January 1892 and capture Bisandugu, gradually forcing Samory to move his empire eastwards.13

In the last decade of the 19th century, Samory's forces campaigned over a vast swathe of territory extending upto to the upper Volta basin of Ghana.

Samori's eastern advance begun with the establishment of a forward base in the Jimini region of north-eastern Ivory Coast. After protracted negotiations, Samori obtained the support of the kingdom of Kong in April 1895. He then thus turned his attention to the Juula town of Bunduku in the kingdom of Gyaman. However, the Gyaman ruler rejected Samori's calls for alliance, beginning a series of battles that ended with the fall of Gyaman's army and the abandonment of Bunduku. But once Samori assured the Juula of Bonduku of his wish for peace, they returned and surrender to him in July 1895.14

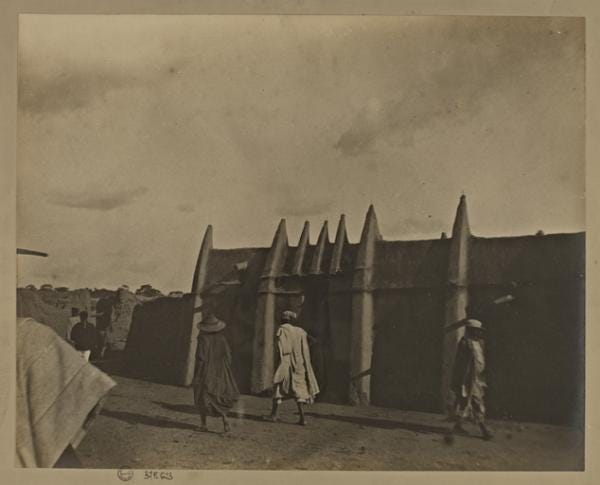

Marabout (Islamic teacher) in Bonduku, 1892, archives nationales d'outre mer

Shortly after his occupation of Bonduku, Samori dispatched envoys to the Asante king Prempeh to explain that he invaded Gyaman because of its ruler's refusal to allow him to open a trade path in that territory, and offered to assist the Asante king to pacify his fragmented kingdom. The Asante king sent a large embassy to Samory in Bonduku in October 1895, with 300 officials and gifts of gold inorder to negotiate a mutual defense pact. Alarmed by the possible resurgence of Asante power, the British hastened plans to invade Asante, and duly informed Samori to not intervene. After their occupation of Asante's capital Kumase, Samori sent an assuring message to the British that he only wished for peaceful trade, but the British remained wary of his intentions and French expansion from the north.15

Samori retuned to Jimini at the end of the year, leaving the newly conquered regions of Gyaman under the care of his son Sarankye Mori who later established himself at Buna. Sarankye Mori entrusted the invasion of Gonja to his subordinate, Fanyinama of Korhogo. The state of Gonja was a confederation of rivaring chiefdoms, one of these was the chiefdom of Kong whose ruler requested Kanyinama's support to defeat its rival, the chiefdom of Bole. Fanyinama's forces quickly occupied Bole by early 1896, and entered a complex pattern of relationships with neighboring states such as the kingdom of Wa which briefly recognized Samori's suzeranity.16

section of Bonduku near one of samory’s residences, photo from the early 1900s

View of Bonduku with one of its mosques.

residence of the ruler of Wa in northern Ghana

State and society in Samory’s second empire until its collapse in 1898.

Like in Wasulu, Samori's new empire in the Upper Volta was mostly administered by a military government and derived its strength from its formidable army. Samori's armies were reputed to be the most disciplined, the best trained and the best armed in west Africa. Samori was able to equip his army with repeating rifles and ammunition.

His officers were armed with Kropatschek rifles (in use by the French army in 1878) and other Gras rifles, (in use by the French army in 1874) while the bulk of the army carried breechloaders, some of which were manufactured locally. The gunsmiths of Samori manufactured single-shot breechloading rifles from scratch at a rate of about a dozen per week. The demand for locally made weapons became more acute as Samori was cut off from Sierra leone. The only other African armies that manufactured guns locally were the Merina kingdom and Tewodros' Ethiopia, although both utilised foreign craftsmen while Samori used local smiths who had worked undercover in St. Louis. Samori’s gunsmiths also made gunpowder, cartridges and spare parts.17

Samori's strength lay not simply in his efficient military but also in his intention to use it as an instrument of radical social reform. Mosques and schools were opened even in small villages where Islamic law introduced, and new converts were recruited into the army. Its also likely that Samory intended to reform agricultural production, replacing the old system of lineage farming with large plantations. But these reforms were poorly received by Samori’s Juula subjects, who rebelled against his rule, prompting him to sack Buna in 1896, executing both its non-Muslim ruler and his Muslim allies.18

Map of Samori’s second empire

Samori's new state also embroiled itself in the internal rivaries of the region's various kingdoms, which inevitably attracted the attention of the French in the north and the British in the south.

Central to this rivary were fears on Samori's side that the ruler of Wa was attempting to form an alliance with the French against him, only for the ruler of Wa to host the British in January 1897. Added to this were rebellions by the Juula of Kong who rejected Samori's legitimacy and were allying with the French. In March 1897 Sarankye Mori defeated a British column under the command of Henderson at Dokita, near Wa, and the threat of Samory's retribution forced Wa to turn to the British. At the same time, Samori sacked the city of Kong in May 1897, executed its senior Ulama, and pushed on to Bobo-Dioulasso where he encountered a French column and retreated.19

Caught between the French and the British, and having vainly attempted to sow discord between the British and the French by returning to the latter the territory of Buna coveted by the former, Samori fled to his allies in Liberia. On the way, he was captured in a surprise attack by the French on 29 September 1898 and deported to Gabon where he died in 1900.20

street scene in Kong, 1892, archives nationales d'outre mer

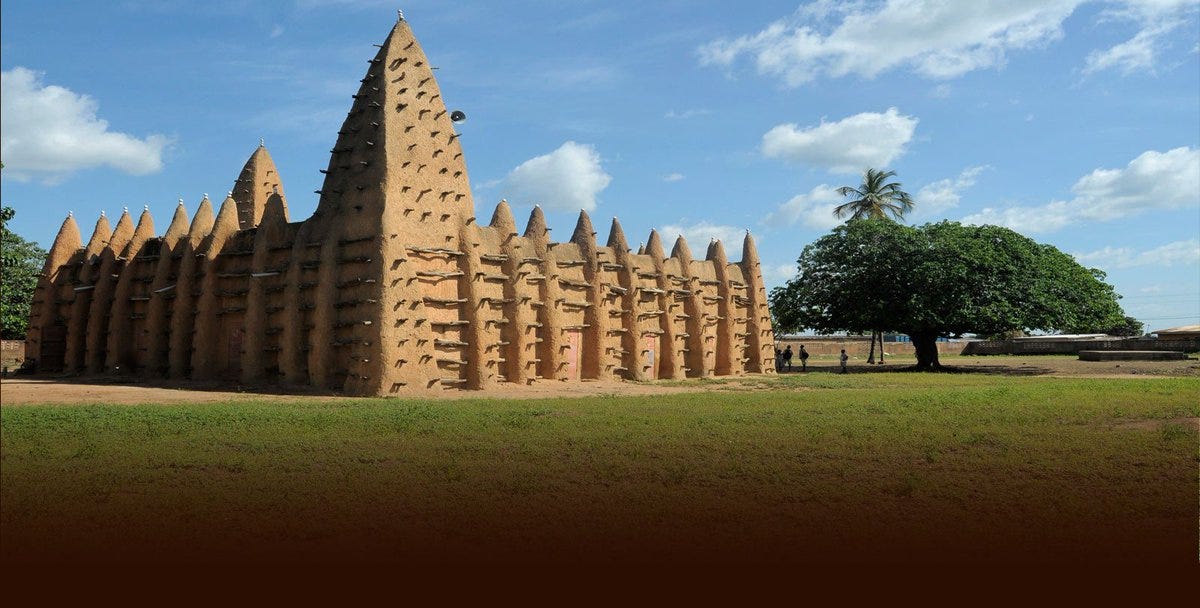

the 18th century mosque of Kong

Samori’s legacy: a struggle for legitimacy.

After the collapse of Samory's state, several dissonant narratives emerged which attempted to characterize its nature, Some of his French foes considered him a 'black Napoleon,' and the archetypal enemy of their "civilizing mission", while the subjects of the formally independent kingdoms he conquered recalled his punitive campaigns in the upper Volta as a period of calamity.

However, none of these perspectives bring us any closer to the internal nature of the state Samori had built. Samori had no sucessors and left no chroniclers or griots to disseminate his propaganda, all that remained after his army was broken were the Juula merchants he was supposedly fighting for, who were at best ambivalent towards his low standing as a scholar and at worst opposed to his use of arms.

It is very difficult to characterize the organization of Samori's state since its structure was in continuous modification. What initially begun as a bourgeoisie revolution evolved into a theocratic empire that later became an anti-colonial state. The common thread uniting these distinctions appears to have been Samori’s struggle for legitimacy.

Despite being a great military strategist, Samori’s rule was never fully accepted as legitimate, unlike the nobility he deposed, he thus found himself constantly at war not just with the colonialists but also with his own subjects, leaving behind a contested legacy of triumph and tragedy.

Samory Ture in Saint Louis, Senegal, January 1899, Edmond Fortier

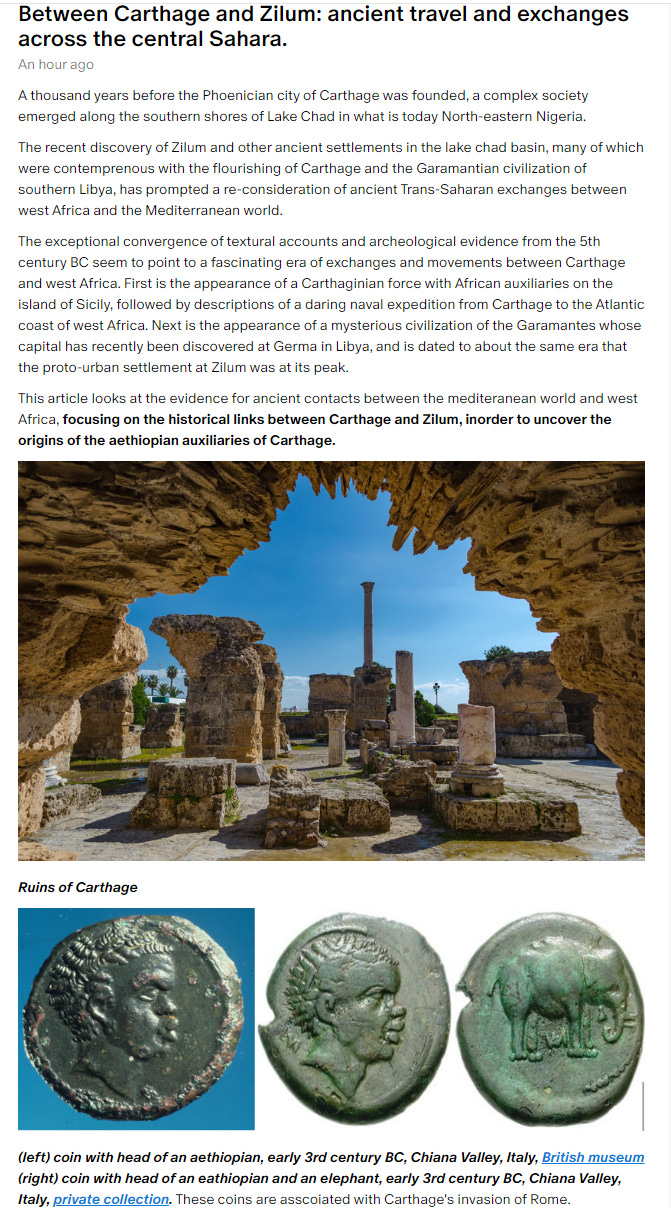

In the 5th century BC, the armies of Carthage invaded the Italian island of Sicily with an army that included aethiopian contigents, around the same time that a proto-urban settlement was flourishing in northern Nigeria, and the Garamantian civilization in the central Sahara.

Read more about the probable links between these three societies and the origins of Carthage’s ‘black African’ armies, on our Patreon:

Traders and the Center in Massina, Kong, and Samori's State by Victor Azarya pg 427-428, Studies in West African Islamic History: Volume 1 By John Ralph Willis pg 263-264)

Studies in West African Islamic History: Volume 1 By John Ralph Willis pg 262-263, 265)

Studies in West African Islamic History: Volume 1 By John Ralph Willis pg 265-266, Traders and the Center in Massina, Kong, and Samori's State by Victor Azarya pg 436-437)

Studies in West African Islamic History: Volume 1 By John Ralph Willis pg 266)

UNESCO General History of Africa, Volume VII pg 125)

Studies in West African Islamic History: Volume 1 By John Ralph Willis pg 268-271)

UNESCO General History of Africa, Volume VII pg 123, Wars of imperial conquest in Africa by Bruce Vandervort pg 130

Studies in West African Islamic History: Volume 1 By John Ralph Willis pg 268, 270-271, UNESCO General History of Africa, Volume VII pg 124)

Traders and the Center in Massina, Kong, and Samori's State by Victor Azarya 438-439, Studies in West African Islamic History: Volume 1 By John Ralph Willis pg 272)

Studies in West African Islamic History: Volume 1 By John Ralph Willis pg 269, 273)

Wa and the Wala: Islam and Polity in Northwestern Ghana By Ivor Wilks pg 121

UNESCO General History of Africa, Volume VII pg 126)

Wa and the Wala: Islam and Polity in Northwestern Ghana By Ivor Wilks pg 120)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 302-304, Making History in Banda: Anthropological Visions of Africa's Past By Ann Brower Stahl pg 98)

Wa and the Wala: Islam and Polity in Northwestern Ghana pg 121-122)

Wars of imperial conquest in Africa by Bruce Vandervort pg 132-133, UNESCO General History of Africa, Volume VII pg 123)

History Of Islam In Africa by N Levtzion pg 107-108)

Wa and the Wala: Islam and Polity in Northwestern Ghana pg 128-140, History Of Islam In Africa by N Levtzion pg 108, West African Challenge to Empire By Mahir Şaul pg 71-72

UNESCO General History of Africa, Volume VII pg 127)

Thank you for this. I'm a historian by inclination, and know more about African history than most Westerners, but I knew none of this and I love learning more about it.

West Africa is starting to come into its own now. I have no chance of understanding what is going on now without understanding where its people came from. Great piece, and nice photos, too.

Damn. This was mindblowing. Samore Toure defeated the Europeans in multiple battles. Not just once, or twice.

That is quite impressive.