On the Enduring Role of Forts and Fortifications in Pre-Colonial African Military history.

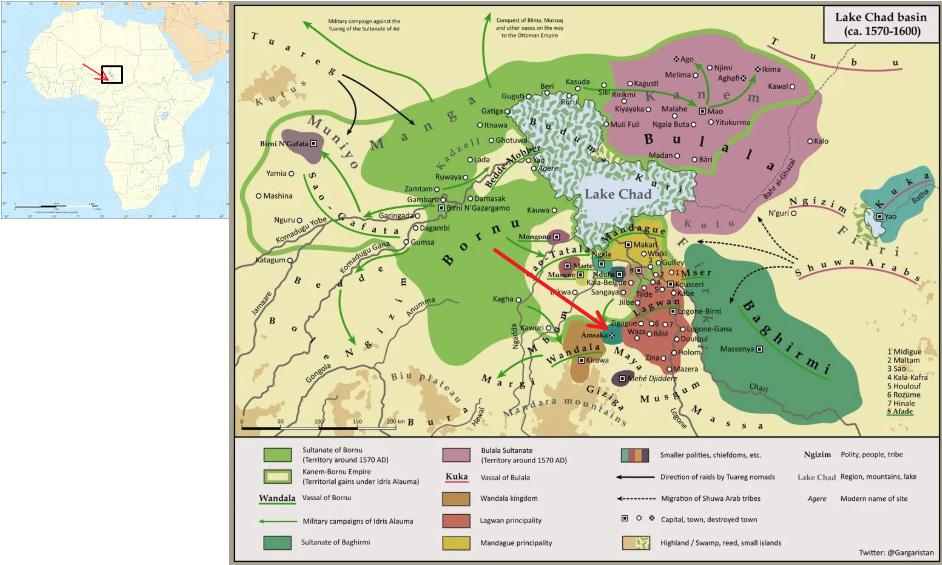

In November 1575, the army of Bornu encamped before the walled town of Amsaka, initiating what would become one of the best-documented episodes of siege warfare in pre-colonial West Africa.

Amsaka, which today would lie along the Cameroon/Nigeria border, was the largest in the string of fortified settlements in the Lake Chad basin, which had long defied Bornu’s suzerainty.

According to the Bornu chronicler Ibn Furṭū, the defenders of Amsaka were confident in the strength of their town’s high walls and deep moat surrounding their town, fortifications that predated the capital of Bornu itself. They taunted their besiegers, saying: “The inside of our fortifications (shawkiyya) and stronghold (Ḥiṣn) will not be seen except by the birds.”1

On the second day of the siege, the defenders mounted the walls and “fired arrows and darts like heavy rain,” forcing the attackers to withdraw. The besieging forces then spent several days attempting to fill the town’s surrounding moat with corn stalks, but the defenders kept coming out at night to remove the stalks. The attackers later shifted their camp to a weaker side of the wall and succeeded in breaching it; however, the opening was swiftly repaired by the defenders. For several days, the defenders threw everything at their attackers, including poisoned arrows, short spears, burning roof materials, and “pots of boiling ordure.”2

To break the stalemate, the Bornu ruler ordered the construction of three [Seige] platforms “so that the musketeers could mount upon them and shoot in the easiest and most advantageous manner at the enemy in the bends of the stronghold (ḥiṣn).” The army also filled the moat with earth until it became flat, and began to batter the town walls, while the gunmen maintained sustained fire against the defenders until they exhausted their supply of arrows. Amsaka was eventually defeated, and its walls were levelled on 4th December 1575.3

Location of Amsaka.

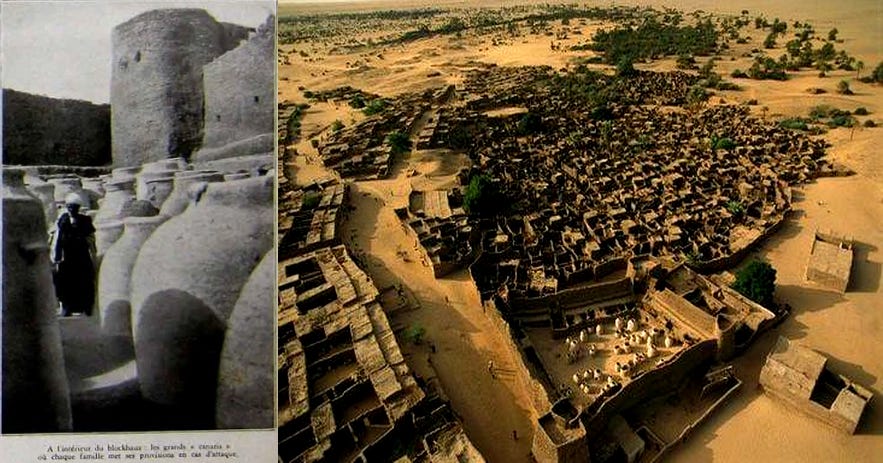

Storage vessels for provisions inside the old fort at Fachi, Kawar, Niger. ca. 1934

walled town on the banks of the Logone river. ca. 1936. Quai Branly

Town wall and moat, Nigeria, circa 1899. Royal Geographical Society

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The history of warfare and military systems in pre-colonial Africa is incredibly complex and quite unlike the spontaneous and short-lived affairs often found in anthropological literature or Hollywood depictions (which are inaccurate even for most European military history4).

The widespread presence of fortifications and other forms of defensive architecture across the continent provides compelling evidence of this complexity, which has until recently been overlooked in African historiography.

While pre-colonial African states often deployed large armies to engage in open-field battles, they also invested in the construction of fortifications and maintained garrisons to defend key towns and settlements.

Particular focus has been given to West African fortifications in historical literature. According to the military historian Robert Smith, “The widespread and numerous remains of fortifications are a recurring and sometimes conspicuous feature in the West African landscape.”5

The earliest of these fortifications, known as a tata, was constructed around the medieval city of Djenné in the 8th century. It played a crucial role in preserving the city’s autonomy throughout much of the Middle Ages, until the Songhay army of Sunni Ali ultimately captured it following a protracted siege in 1480.6

Continued advancements in military technology and siege tactics led to the evolution of defensive systems: walls were constructed thicker and taller, observation towers were added, and galleries or platforms to provide gunmen with elevated positions from which to engage attacking forces.7

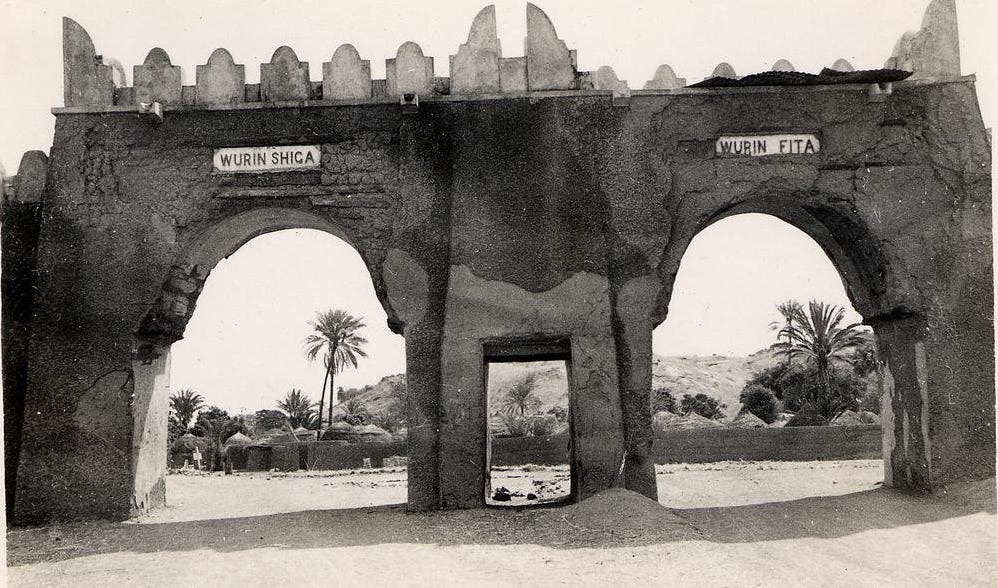

Remains of a double-arched gate of a city wall, with a platform for archers. ca. 1880-1950. Bauchi, Nigeria. British Museum

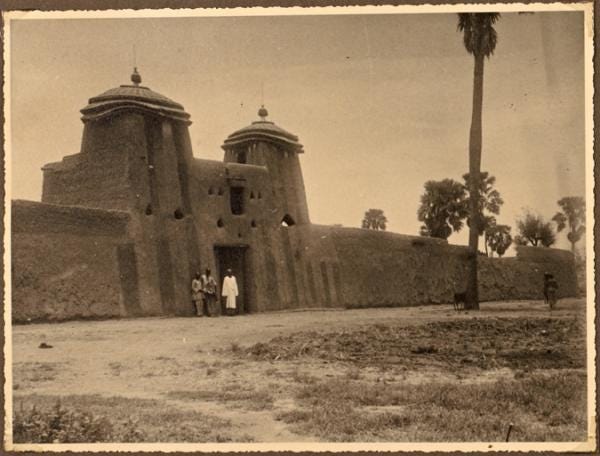

Gate in the city walls of Logone-Birni, ca. 1930, Cameroon. ANOM

Tata of Tiong-i, Mali. ca. 1892. illustration by L. Binger. “Tiong or Tiong-i has the appearance of a city: its large clay walls of ash gray clay with coarse flanking towers spaced 25 to 30 meters apart”

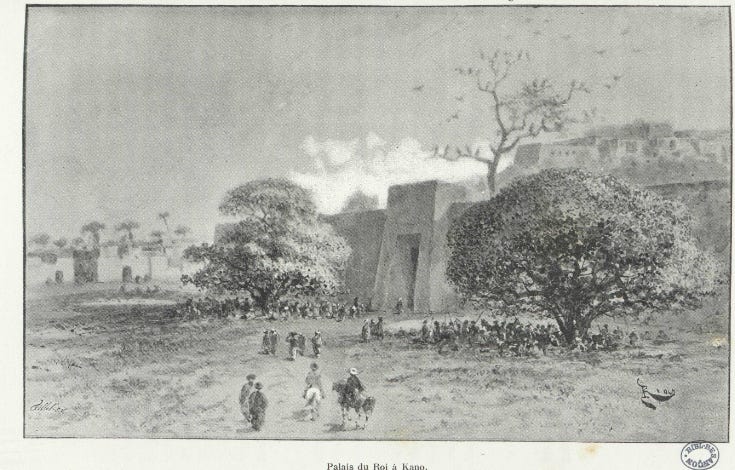

Entrance to the palace of the emir of Kano, Nigeria, ca. 1891

The French traveler Mungo Park documented several fortifications in the Upper Niger region (present-day Mali) built of stone and clay, many of which were loopholed and constructed for fighting with gunpowder weapons. His account also describes counterworks used to attack a fortified place, e.g., during the Segu invasion of the town of Sai in 1782, when the former constructed a complex network of trenches complete with square towers at regular intervals, some 200 metres from the town walls.8

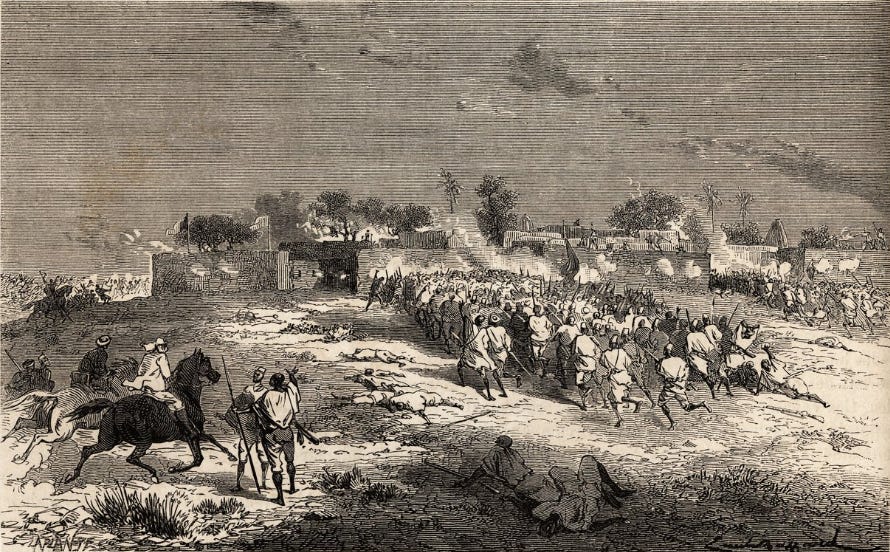

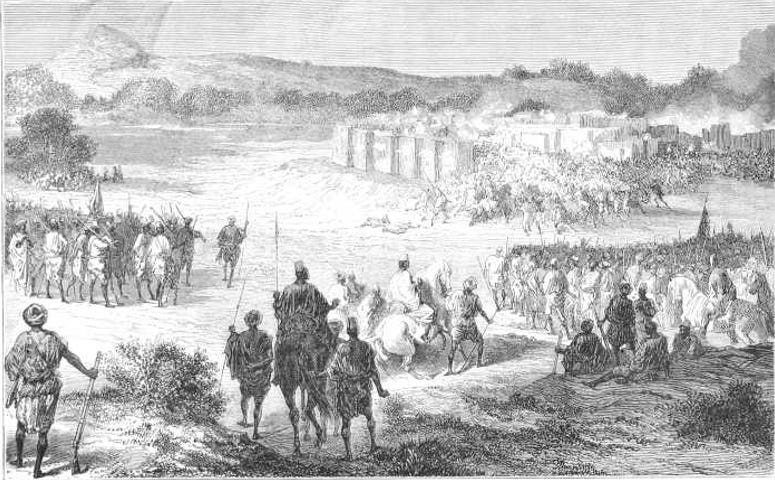

During his conquest of Segu, the Tukulor ruler Umar Tal deployed artillery against the walled town of Woitala in December 1860. Initially, the defenders “poured a withering fire on the advancing columns,” and only a single artillery round was fired before the wheels of the carriages collapsed. Umar subsequently assigned his blacksmiths to repair the cannon and their carriages. After several days, his forces bombarded the fortifications with artillery, scaled the walls using ladders, and ultimately captured the city.9

Similar assaults against the fortified towns of Sansanding and Dina were later undertaken in 1865 by the Tukulor armies, all of which involved lengthy sieges supported by artillery fire from bronze howitzers, copper pierriers, and iron mortars captured from the French.10

‘Attaque de la pointe des Somonos à Sansandig’. Engraving by Eugène Mage, ca. 1868

‘Assaut de Dina.’ Engraving by Eugène Mage, ca. 1868

Umar Tal constructed several fortifications capable of withstanding contemporary military technology, the most notable of which were the stone forts at Koundian, Nioro, Farabugu, and Koniakary, built in 1857.11

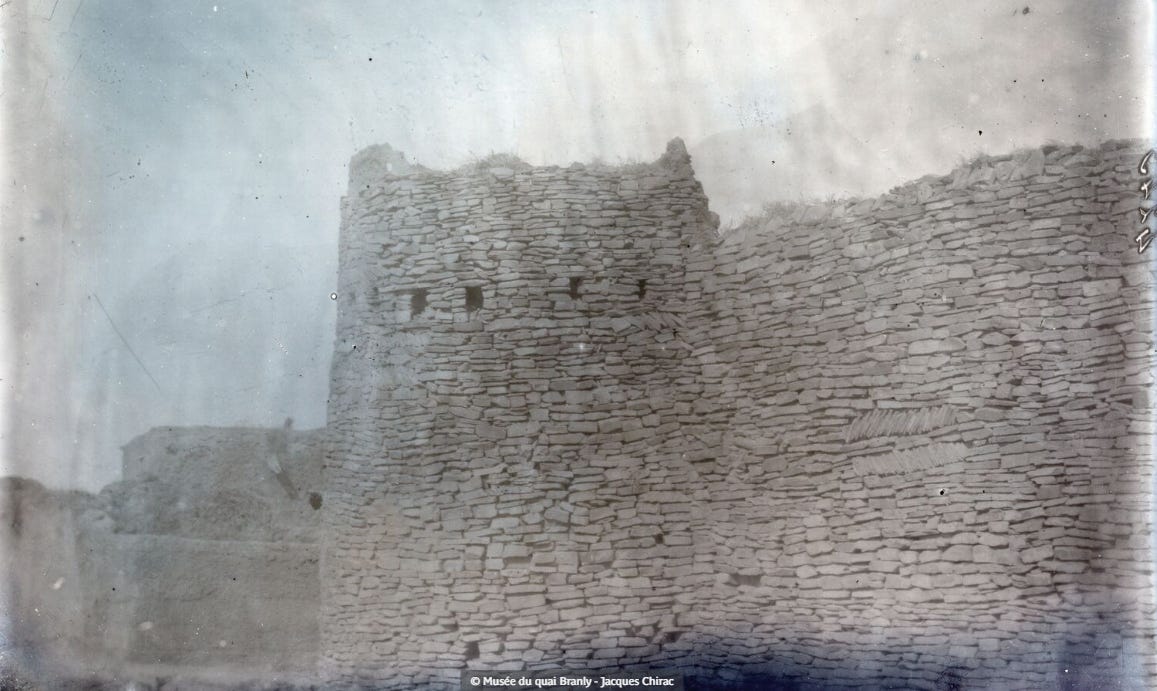

The fort at Nioro was described by the French traveler Eugène Mage: “This fortress is a vast square measuring 250 feet each side built regularly in stones faced with earth, the walls are 2.5 m thick; on the four corners there are round towers and the whole is between 10 and 12 meters high... It is absolutely impenetrable without artillery.”12

During the French invasion of Tukulor in 1889-93, tactical miscalculations by the Tukulor ruler Ahmadu, whose armies met the colonial armies of Louis Archinard in the open, left the fortresses of Koniakary and Nioro undefended.

Nevertheless, the small contingents left to defend other strongholds, such as the 300-man garrison at Koundian, mounted significant resistance. The fortress’s double walls of masonry stood up well to the fire of Archinard’s 80 mm mountain guns, and the defenders stood firm under bombardment until a breach was made through the walls after 8hours of uninterrupted artillery barrage.13

Breach at Koundian, Dry stone construction partially collapsed. ca. 1880-1889. Quai Branly

A tower of the Nioro fort. ca. 1889-1894. ANOM

The entry of the cannon pieces into the Nioro fort. Mali. ca. 1889-1894. ANOM

Nioro fort. Mali. ca. 1889-1894. Quai Branly.

‘Tata de Koniakary’, Mali.

The slow and uneven spread of gunpowder weapons meant that these fortifications remained the most effective means of defensive warfare in Africa until the close of the 19th century, when more modern weaponry used by colonial armies proved decisive against both the fortifications and their defenders.

Examples of fortifications that forced colonial armies to rely on heavy artillery include the walled cities of Yorubaland (e.g., at Bida in 1897) and the Bukusu forts of Kenya (e.g., at Chetambe in 1895). As late as 1902, the heavily fortified zawiya (Sufi lodge) of Bir Alali in Kanem (present-day Chad) served as a major military stronghold for local resistance against the French, with operations supported and coordinated by the Sanusiyya movement.

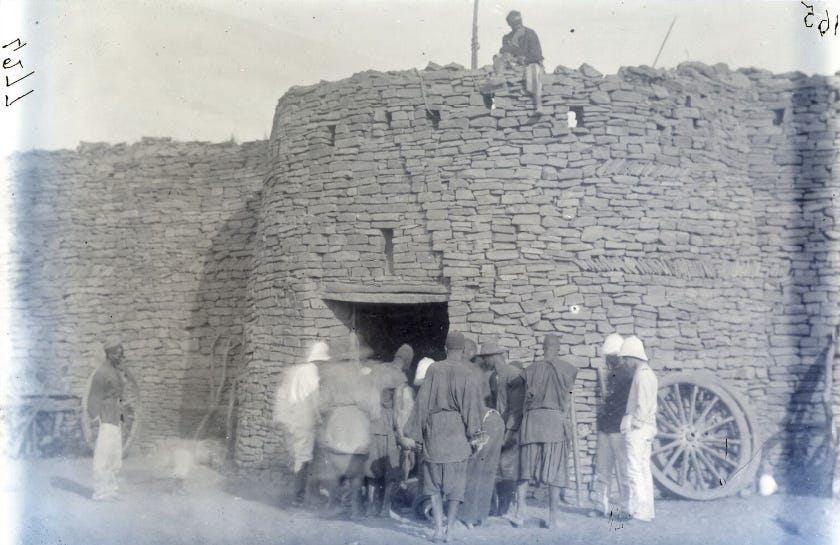

One of the clearest demonstrations of the enduring strategic value of such fortifications is provided by the Dervish movement of Muḥammad ʿAbdille Ḥasan in present-day Somaliland, which held out against British incursions from 1899 to 1920.

During the opening years of the 20th century, the dervishes, who were hemmed in by the British, Italians, and the Ethiopians, transformed their military systems from guerrilla warfare to a more static form of defensive warfare by constructing several massive stone fortresses with 12-14 ft thick walls rising 35-50ft above the barren landscape.

From these formidable strongholds, Hassan’s dervishes repelled several British assaults and carved out a state in the interior. It was only after the invention of warplanes and the use of aerial bombardment at the close of the First World War that colonial forces were able to subdue the Dervishes and dislodge them from their forts.

This history of the stone forts of Somaliland is the subject of my latest Patreon Article. Please subscribe to read more about it here and support this newsletter:

Taleh, Somaliland, ca. 1997.

A Sudanic Chronicle: The Borno Expeditions of Idris Alauma (1564-1576) By Aḥmad Ibn Furṭū, Dierk Lange, pg 60

History of the First Twelve Years of the Reign of Mai Idris Alooma of Bornu (1571-1533) By Aḥmad Ibn Furṭū, Richmond Palmer 60-61)

A Sudanic Chronicle: The Borno Expeditions of Idris Alauma (1564-1576) By Aḥmad Ibn Furṭū, Dierk Lange, pg 61-63

for a great introduction on the historical inaccuracies in modern films, read: Past Imperfect: History According to the Movies by Mark C. Carnes

Warfare & Diplomacy in Pre-colonial West Africa By Robert Sydney Smith pg 127

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 20-22

Warfare & Diplomacy in Pre-colonial West Africa By Robert Sydney Smith pg 129-153

Warfare in Atlantic Africa, 1500-1800 By John Kelly Thornton pg 30

The Holy War of Umar Tal: The Western Sudan in the Mid-nineteenth Century By David Robinson ·pg 260-261

The Holy War of Umar Tal: The Western Sudan in the Mid-nineteenth Century By David Robinson ·pg 250. on Ahmadou’s assault on Sansanding and Dina, see: Voyage dans le Soudan occidental (Sénégambie-Niger) by E. Mage

UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. VI Africa in the Nineteenth Century Until the 1880s, pg 626

Making and Remaking Mosques in Senegal By Cleo Cantone, pg 66-67

West African Resistance: The Military Response to Colonial Occupation By Michael Crowder