State building in pre-colonial Somalia: the Sultanate of Geledi (ca. 1750-1908)

For much of Somalia’s pre-colonial history, political organization was structured along clan and lineage divisions within largely acephalous societies. However, in some of these societies, powerful rulers emerged whose authority was consolidated through networks of alliances that united multiple clans into more cohesive polities.

Throughout the 19th century, the principal center of power in southern Somalia was the Kingdom of Geledi, whose sultans presided over a confederation of clans that controlled the rich agricultural hinterland between Mogadishu and Brava.

The sultans of Geledi were recognized as the rulers of an increasingly centralized and wealthy state that forged alliances with the East African coast. They also hosted European commercial envoys, whose accounts provide valuable insights into the extent of state formation and political organization before the onset of colonial rule.

This article examines the political history of the Geledi state in the nineteenth century.

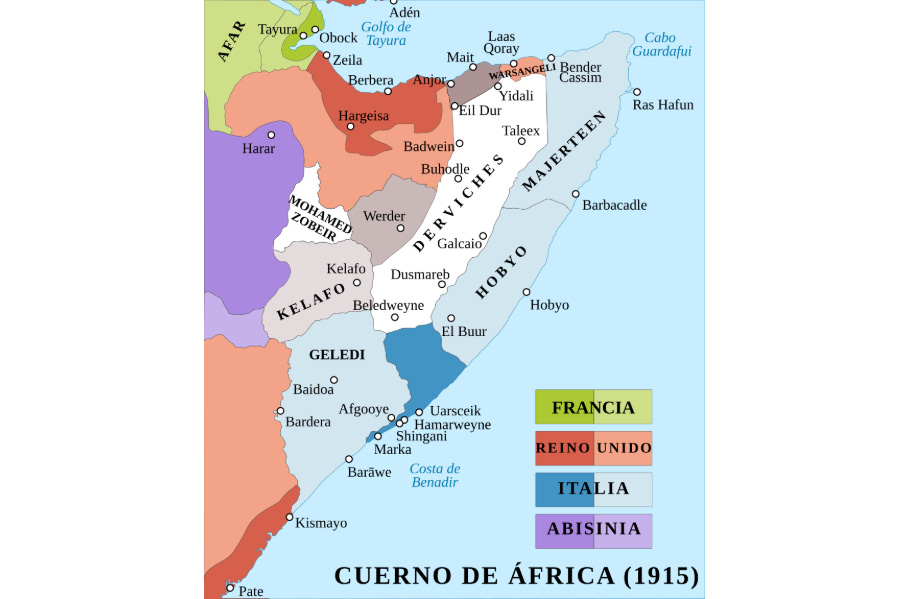

Map of Somalia in the early 20th century.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by joining our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Early history of Geledi.

Historical and oral sources indicate that by the close of the Middle Ages, the Ajuran (Ajuuraan) Empire exercised hegemony over much of southern Somalia; however, its political dominance gradually declined over the course of the 17th century.

In the region of the lower Shabeelle river, historical traditions about the end of the Ajuuraan hegemony refer to their deputies or successors as the Silcis. The latter were considered by their successors to have been unpopular rulers, whose sultan exacted tribute from the surrounding populations and taxed all livestock.1

In the 18th century, the Silcis sultans were ousted by the combined forces of the Geledi and Wacdaan, whose alliance began during the early part of the century. As in many parts of southern Somalia, memories of having defeated the Ajuuraan embellish a clan’s history, and long-standing alliances assume a sense of permanence by having begun in rebellion against a common oppressor.2

Map of Southern Somalia showing the approximate extent of Ajuran in the 16th century.

The early state of Geledi was a confederation comprised of a system of alliances between multiple lineage groups headed by the Geledi clan, and the allied clans of Wacdaan and Murusade, who considered it to be an alliance between equal entities. Support from other clans, such as the Hintire, Tunni, Begeda, Jambeluul, and Jiddu, and others depended on the perceived success of the rulers.3

In the second half of the 18th century, a family known as the Gobroon, who were regarded as saints in Islamic tradition, became the dominant force among the lineages that made up the Geledi clan, with their sheikh becoming the religious and political head or ‘suldaan’/Sultan.4

The sultan was elected by an assembly of the heads of the main lineages, who selected and installed the most suitable candidate from the Gobroon elites. The first of these sultans was Ibraahim Adeer, the grandfather of Yuusuf Maxamuud (d. 1848), whose reign is better documented.5

Sultan Yuusuf hosted William Christopher of the British East India Company, who visited “Giredi, the capital of Sheikh Sultan Yusuf bin Mohammed” in 1843:

“Here the government is mild… this great Somali chief could bring 20,000 spearmen into the field, perhaps 50,000, if he made large promises to and flattered the more republican-spirited districts, which nominally own his authority.”

William’s arrival coincided with preparations for a major campaign by the Geledi sultan against the ‘Barderh’ (Bardheere). The latter was a militant reformist movement in the interior, whose members reportedly ‘stigmatized’ Geledi as less orthodox in their religious practices.6

He adds that the ‘sultan of Bardeh’ had recently attacked the coastal town of Brava/Baraawe around 1840. Brava had to submit to the rigours imposed by the Bardera reformers: tobacco and popular dancing were forbidden, restrictions were imposed on women’s clothing, and the ivory trade ceased. In response, the Geledi sultan restored his suzerainty over the town, revived the old practices, and resolved to defeat the Bardheere movement.7

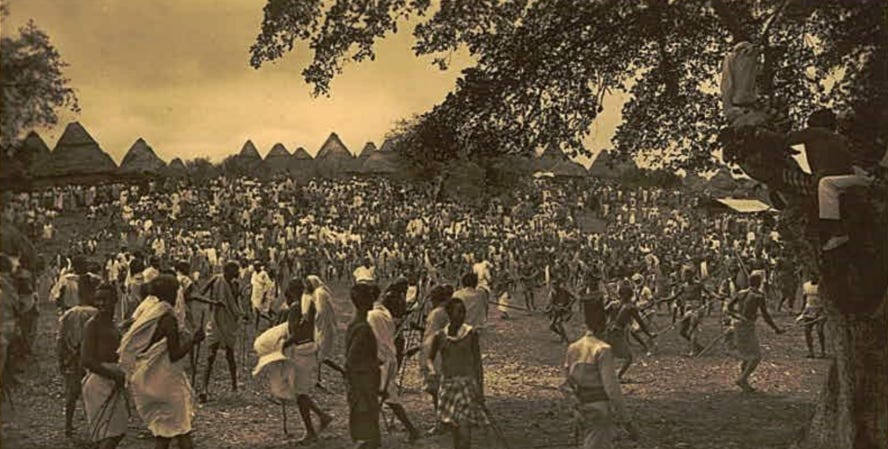

In 1843, Sultan Yuusuf set out from his capital with a large army comprised of many allied clans and camped before the walls of the Baardheere capital. After a siege that lasted several days, Yuusuf’s forces stormed the town and sacked it.

This account was recounted to the French captain, Charles Guillain, who visited ‘Gueledi’ in 1847-8 to explore the commercial possibilities of East Africa. He left a fairly detailed description of the capital and the sultanate, but never managed to meet with the sultan ‘Youceuf-ben-Mahhmoud.’8

While at the capital, he mentions a ‘document which I collected myself,’ that was a genealogy of the sultan tracing his descent back 14 generations to ‘Guebron’ (Gobroon), the supposed founder of the ruling dynasty of the Geledi. He and other visitors also mention written correspondence and other documents that were used and read by the Sultan and his officials, and were exchanged with coastal scholars.9

One such letter, written by Hajji Ali of Majeerteen to his allies in Brava, mentions that the author was part of the forces that battled against the Sultan of Geledi around 1847, with the hope of restoring the Bardheere movement. He cautions his allies that “if you follow the sectarian crowd of the unbeliever Yusuf [of Geledi], there will no longer be bonds of family between us.” His forces were defeated by Geledi’s army.10

The latter advice was likely ignored, along with plans to restore the movement, and the town of Brava remained loyal to the Geledi sultan, although it retained its internal autonomy.

In response to the defeat of the Bardheere, the genealogical and religious unity symbolized by the Geledi sultan assumed the reality of a military alliance. Some of the outlying clans, which had previously shown nothing more than a distant respect for the religious powers of the Gobroon, accepted the status of raia (subjects) to ensure Yuusuf’s protection.11

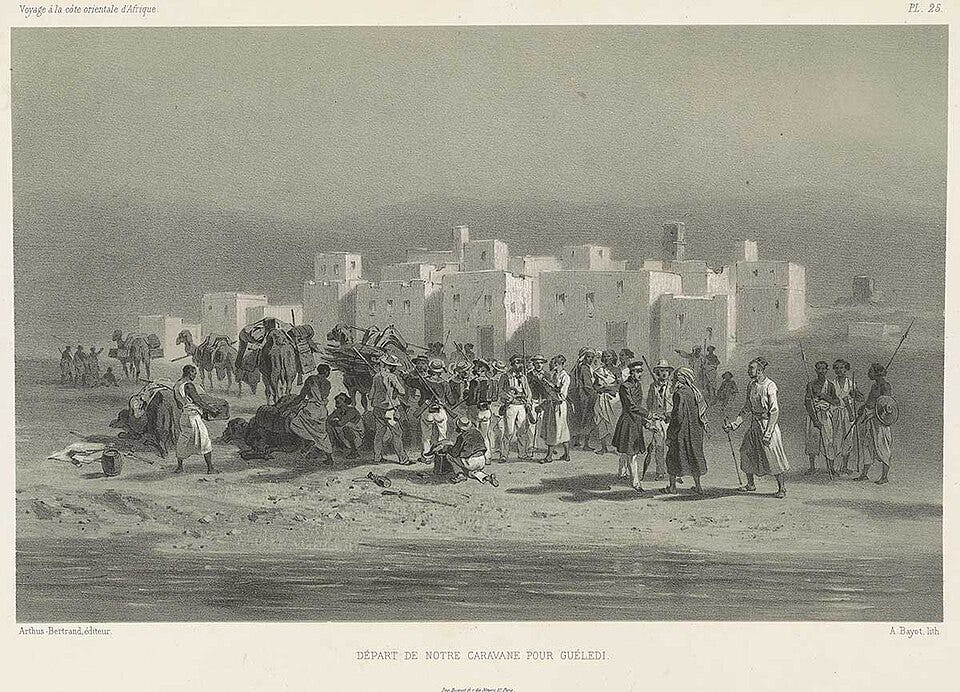

Departure of Guillain’s caravan for Gueledi, from Mogadishu. ca. 1856

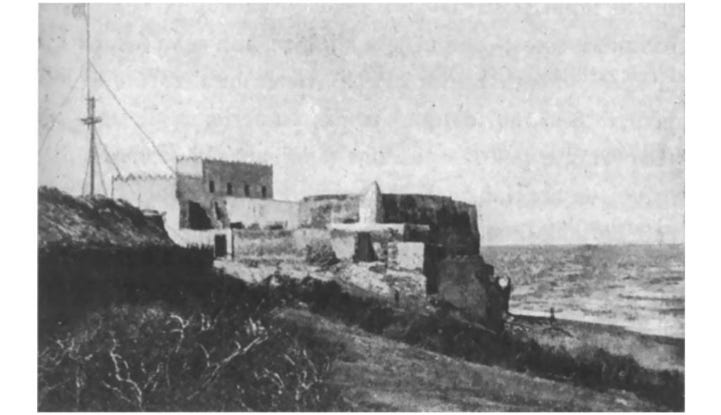

The Jami mosque and the wali’s house in Brava. ca. 1899

State and society in 19th-century Geledi

The sultan of Geledi was at the head of an elaborate system of government with ranked office holders (ul-hay), who acted as a link between the sultan and the rest of the clan. They constituted a council of representatives for each lineage group, and convened a general assembly (kulun) where political matters and decisions were made.

Below them were officials (gogle or sagaale) in charge of collecting taxes and acted as the sultan’s messengers. Besides these were the holders of individual offices, such as the two military leaders, the malaakh and the garaad, who led the core of the army.12

The capital, originally called Geledi but later known as Afgooye after one of its quarters, was a fairly large settlement, with an estimated population of 6-7,000 at the time of Guillain in the 1840s. This estimate compares favorably with the population of the coastal towns at the time, like Mogadishu at 5,000, Marka at 3,500, and Brava/Baraawe at 5,000. Geledi was composed of three settlements, containing walled compounds of roundavels, intersected by wide, winding streets.13

‘View of Gueledi’ (Afgooye), by C. Guillian. ca. 1856.

Throughout the lower Shabeelle region, there existed numerous communities of farmers of different origins who were incorporated as dependents and clients of the pastoral clans. They included pre-existing farming groups, mixed agro-pastoral groups, and captives that had been brought from the East African coast and Ethiopia.14

Like other client groups, they provided warriors for the army; received a portion of the spoils of war; and participated in some of the religious ceremonies of the larger confederation. They typically enjoyed uncontested rights to the land they worked, but the clans were the ultimate guarantor of the land. A client lineage typically inhabited and worked the land of a particular bilis (”noble”) lineage, whose elders in turn represented their clients in the councils.15

The common unit of measurement of agricultural land was a darab, four of which comprised an alguud, which is roughly equal to a hectare. Farm sizes ranged from 7-29 hectares, and land could be rented out to clients, but was rarely sold. The mixed agro-pastoral economy of Geledi produced a large surplus of grain, sesame, and cotton, some of which was exported to the southern coast of Arabia.16

Most of the major trade routes from the interior to Mogadishu converged at the capital, where, according to Guillain, the sultans collected transit fees and gifts from caravan traders travelling to the coast.

At Mogadishu in 1873, the traveller John Kirk ‘was much struck with the number of large dhows at anchor. . . We found twenty vessels from 50 to 200 tons, all filled with or taking in native grain, which I learnt is largely grown on the river behind, near Geledi.’17

By the mid-19th century, the sultans were actively involved in coastal trade.

The sultan Yuusuf Maxamuud had close ties with Bwana Mataka, the deposed Swahili ruler of Siyu (in Kenya), with whom he was allied since the early 19th century against the Baardheere movement. The two maintained a network of alliances along the Jubba river that consisted of mixed communities of Oromo-speakers and freed slaves (watoro) who controlled the ivory route to the coast that had been blocked by the Baardheere leaders.18

One of Yuusuf Maxamuud’s first measures as he sought to restore tranquility to the area after his assault on Baardheere was the revitalization of the ivory trade to Brava. In the 1860s, His successor, Axmed Yuusuf, was reported to be receiving some 3,000 thalers annually from the heads of that town.19

The agricultural boom of the 19th century strengthened the economic position of the riverine clans vis-à-vis their coastal counterparts. Control over the supply of commodities enabled the Geledi rulers to exercise a certain leverage over politics in the coastal towns.

A succession dispute in Mogadishu between the leaders of the two quarters of Shangani and HamarWeyne in 1843 was briefly resolved by the Geledi sultan, who had close ties with the latter, and compelled one of the rival candidates to move inland.20

‘The fort (Garessa) of Mogadishu, with Fakr ad-Din Mosque and HamarWeyne on the left and Shangani on the right.’ image and caption by ‘Mogadishu: Images from the Past’

Consolidation and decline.

In 1848, the Sultan Yuusuf Muhammad died in a battle against the Biimaal outside the coastal town of Marka. The Biimaal was one of the few southern clans that hadn’t joined Yuusuf’s original alliance. Yuusuf’s son and successor, Axmed, succeeded in regaining the allegiance of the core groups in the confederation, and stationed his brother Abukar in the frontier region to repel Biimaal attacks.21

During the 30 years of Axmed’s reign, Geledi remained a major force in the politics of the region, retaining considerable influence on the coastal towns.

In 1868-70, the liwali (governor) of Lamu (in Kenya) extended his influence to the port town of Kismayo (in southern Somalia), where he assisted the Majeerteen Somali to drive off Brava-nese and Oromo merchants that wanted to control its ivory trade. The latter thus called on their suzerain, Axmed Yuusuf, prompting the liwali of Lamu to reinforce the garrison at Kismayo. This resulted in a stalemate that only ended with Axmed's demise nearly a decade later.22

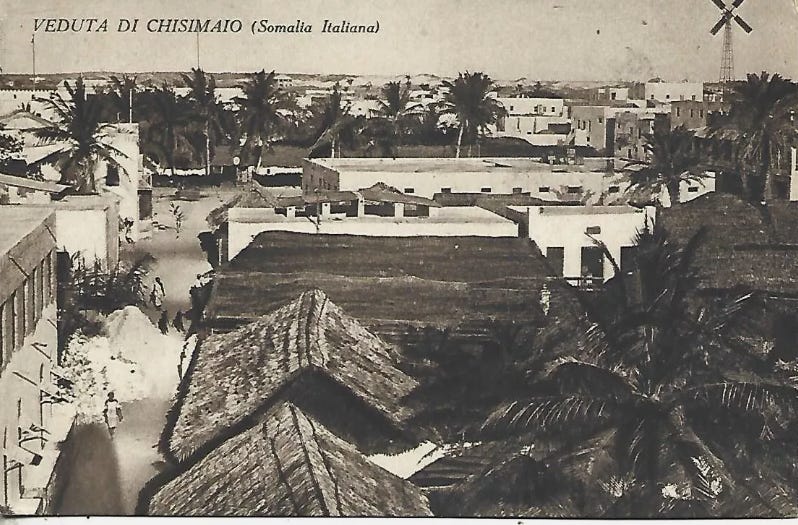

Kisimayo, Somalia. ca. 1935.

Axmed briefly forged an alliance of convenience with the Sultan Bargash of Zanzibar in the 1870s over the commercial and political affairs of Mogadishu, at the expense of the Shangani quarter.

When the leader of Shangani refused to let Sultan Seyyid Barghash build a garrison in Mogadishu, his intransigence was overcome by Sultan Axmed’s threat to impose a boycott on the Shangani market and by the agreement of the sultan of Zanzibar not to send his officials inland as a price for the sultan of Geledi’s support. The Shangani leadership soon saw the merit of Axmed’s position, and the garrison was built.23

In the interior, a series of indecisive skirmishes between the army of Geledi and the Biimaal culminated in a major encounter in 1878, which ended with the defeat of Sultan Axmed. His successors split the state between themselves, forming rival power bases, and many of the confederation’s former allies began to assert their independence from Geledi leadership.24

Geledi influence along the caravan routes had also declined, as many caravans diverted their routes through Awdheegle to Marka, in Biimaal territory. The leader at the capital was Sultan Cusmaan, who hosted the French traveler Georges Revoil in 1882. Revoil reported that the sultan had great difficulty controlling his old allies, and his tribute had diminished considerably.25

On numerous occasions, foreign merchants were discouraged from visiting the Shabeelle Valley because of reported Somali fears that their land would be coveted and eventually seized by outsiders. These fears turned out to be well-founded, as the region’s productive potential attracted the interest of Italian colonial officials during the 1890s, after the Sultan of Zanzibar, Sayid ‘Ali, had, in 1892, granted the Banaadir ports to Italy for a period of 25 years.26

In November 1896, the Italian colonial official Antonio Cecchi set out with a small force to meet with Sultan Cusmaan at his capital. His expedition was besieged and destroyed at Lafoole, along the road from Mogadishu, by a section of warriors from the Wacdaan, the former allies of Geledi. The Sultan, who was the head of a large community of divergent interests, is thought to have restrained his followers from taking part in the attack.27

Some among the Geledi, especially wealthy landowners and merchants, favored a policy of accommodation with the Italians, and continued to correspond with the Italian authorities from 1896 to 1907.

The Sultan, on the other hand, mistrusted the Italians, despite visiting Mogadishu in 1902 and signing a treaty of protection against the dervishes of the ‘Mad mullah’ (Sayyid Maxamed Cabdulle Xasan). The latter was waging an anti-colonial war against the British and Ethiopians, when his forces attacked the Geledi region, ostensibly, in response to their alliance with the Italians.28

In the first decade of the 20th century, the authority of the sultan was reduced to the capital and its immediate hinterland. Former allies such as the Hintire had broken away from the confederation and had inflicted a humiliating defeat on his forces in 1903-4, forcing him to seek protection from the Italians.

When the Italians finally decided to occupy the Geledi capital in 1908, the Sultan welcomed them because they had pacified the Hintire and Biimaal. Most of his remaining subjects in Geledi followed him, while the rest defected to join the groups still opposed to colonial rule.

With the full establishment of Italian control after 1910, the Geledi confederation was split up into four administrative units. The colonial administrators initially allowed the sultan Cusmaan to retain some authority, but this ended with his death in 1920.29

The regional alliances that had enabled the confederation to flourish, and were in decline at the end of the century, splintered further due to divergent responses to the imposition of colonial rule, and would remain fragmented for most of the 20th century.

ceremonial ‘stick-fight’ in Afgoi, ca. 1920.

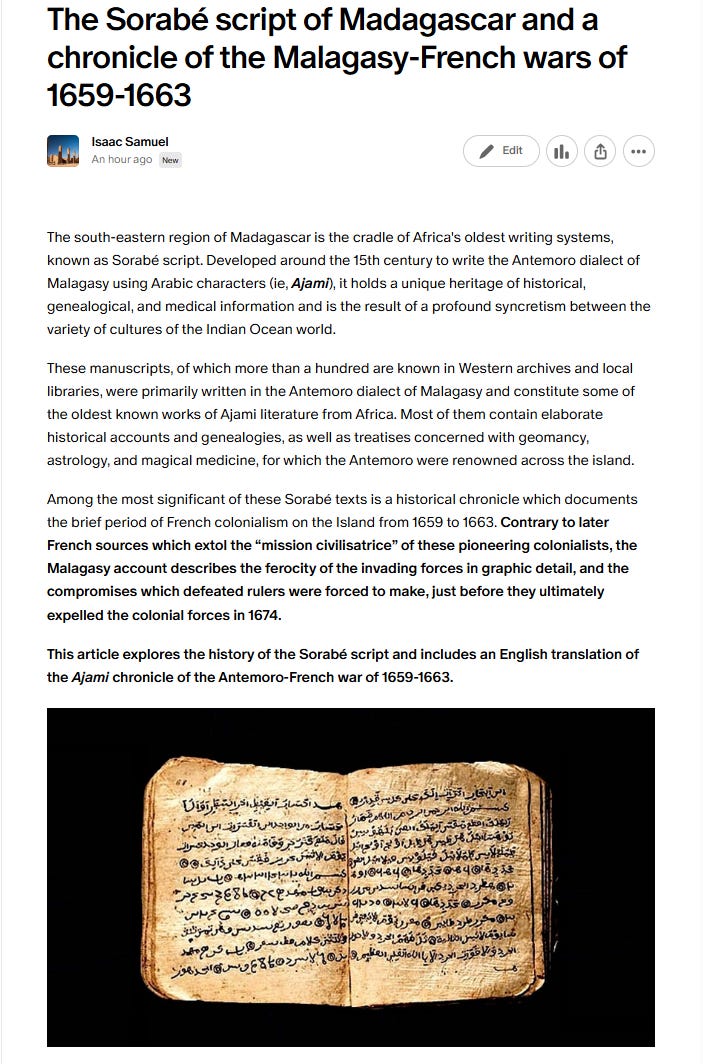

Before the introduction of the Latin alphabet during the colonial period, the most widely used writing system in pre-colonial Africa was the ʿAjamī script

The rich archival collections of Ajami literature represent an untapped mine of information for a comprehensive reconstruction of Africa’s past.

My latest Patreon article explores the history of Sorabé, an Ajami script used in Madagascar since the 15th century.

Please subscribe to read more about it here and support this newsletter:

Somali Sultanate: The Geledi City-state Over 150 Years by Virginia Luling, pg 17-19, 274-276

The Shaping of Somali Society: Reconstructing the History of a Pastoral People, 16-19 by Lee V. Cassanelli, pg 111

Somali Sultanate: The Geledi City-state Over 150 Years by Virginia Luling, pp. 180- 183, 207- 209

The Shaping of Somali Society: Reconstructing the History of a Pastoral People, 16-19 by Lee V. Cassanelli, pg 131-132)

Somali Sultanate: The Geledi City-state Over 150 Years by Virginia Luling, pg 20-21, 176-178)

The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society: JRGS, Volume 14 By Royal Geographical Society pg 89-90, Renewers of the Age: Holy Men and Social Discourse in Colonial Benaadir, By Scott Steven Reese, pg 55-56

The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society: JRGS, Volume 14 By Royal Geographical Society, pg 92-93

The Shaping of Somali Society: Reconstructing the History of a Pastoral People, 16-19 by Lee V. Cassanelli, pg 138, Documents sur l’histoire, la géographie et le commerce de l’Afrique orientale, Part 2, Volume 2 by Charles Guillain, (Paris : Arthus Bertrand , 1856) Pg 17-44

Tradition to text: writing local somali history in the travel narrative of Charles Guillain (1846–48) by Lee V. Cassanelli, pg 64-66

Patricians of the Benaadir: Islamic Learning, Commerce and Somali Urban Identity in the Nineteenth Century by Scott Steven Reese, pg 54. Tradition to text: writing local somali history in the travel narrative of Charles Guillain (1846–48) by Lee V. Cassanelli, pg 66-68,

The Benaadir Past: Essays in Southern Somali History by Lee V. Cassanelli, pg 103

Somali Sultanate: The Geledi City-state Over 150 Years by Virginia Luling, pg 174-176

Somali Sultanate: The Geledi City-state Over 150 Years by Virginia Luling, pg 41-42

Somali Sultanate: The Geledi City-state Over 150 Years by Virginia Luling, pg 115-121, The Bantu-Jareer Somalis: Unearthing Apartheid in the Horn of Africa by Mohamed A. Eno, pg 81-88.

The Shaping of Somali Society: Reconstructing the History of a Pastoral People, by Lee V. Cassanelli, pg 164-165

Somali Sultanate: The Geledi City-state Over 150 Years by Virginia Luling, 144-149

Muqdisho in the Nineteenth Century: A Regional Perspective by EA Alpers, pg 449, Somali Sultanate: The Geledi City-state Over 150 Years by Virginia Luling, pg 164-166

The Ivory Trade in the Lamu Area, 1600-1870 by Marguerite Ylvisaker, pg 225, 229, The Origins and Development of the Witu Sultanate pg 672-673

The Shaping of Somali Society: Reconstructing the History of a Pastoral People, by Lee V. Cassanelli, pg 140, Somali Sultanate: The Geledi City-state Over 150 Years by Virginia Luling, pg 178

Muqdisho in the Nineteenth Century: A Regional Perspective by EA Alpers, pg 445-447

Somali Sultanate: The Geledi City-state Over 150 Years by Virginia Luling, pg 24-25

Lamu in the Nineteenth Century: Land, Trade, and Politics by Marguerite Ylvisaker, pg 99-100, 120.

Muqdisho in the Nineteenth Century: A Regional Perspective by EA Alpers, pg 453

M. Revoil’s Journey into the South Somali Country, Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society and Monthly Record of Geography, New Monthly Series, Vol. 5, No. 12 (Dec., 1883), pg 717-718. The Shaping of Somali Society: Reconstructing the History of a Pastoral People, by Lee V. Cassanelli, pg 188, 208-209, Somali Sultanate: The Geledi City-state Over 150 Years by Virginia Luling, pg 26-28

The Shaping of Somali Society: Reconstructing the History of a Pastoral People, by Lee V. Cassanelli, pg 189

The Shaping of Somali Society: Reconstructing the History of a Pastoral People, by Lee V. Cassanelli, pg 176

The Shaping of Somali Society: Reconstructing the History of a Pastoral People, by Lee V. Cassanelli, pg 203-204, 209-210)

Somali Sultanate: The Geledi City-state Over 150 Years by Virginia Luling, pg 210-213, The Shaping of Somali Society: Reconstructing the History of a Pastoral People, by Lee V. Cassanelli, pg 30-31

Somali Sultanate: The Geledi City-state Over 150 Years by Virginia Luling, pg 31-34, 191-194).

Very interesting