State, Society and Ethnicity in 19th century Adamawa

Most of the largest states in pre-colonial Africa were made up of culturally heterogeneous communities that were products of historical processes rather than ‘bounded tribes’ with fixed homelands.

The 19th-century kingdom of Adamawa represents one of the best case studies of a multi-ethnic polity in pre-colonial Africa, where centuries of interaction between different groups produced a veritable ethnic mosaic.

Established between the plains of the Benue River in eastern Nigeria and the highlands of Northern Cameroon, Adamawa was the largest state among the semi-autonomous provinces that made up the empire of Sokoto.

This article explores the social history of pre-colonial Adamawa through the interaction between the state and its multiple ethnic groups.

Map of 19th-century Adamawa and some of its main ethnic groups1

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Historical background: ethnogenesis and population movements in Fombina before the 19th century.

At the close of the 18th century, the region between Eastern Nigeria and Northern Cameroon was inhabited by multiple population groups living in small polities with varying scales of political organization. Some constituted themselves into chiefdoms that were territorially extensive, such as the Batta, Mbuom/Mbum, Tikar, Tchamba, and Kilba, while others were lineage-based societies such as the Vere/Pere, Marghi, and Mbula.2

The Benue River Valley was mostly settled by the Batta/Bwatiye, who formed some of the most powerful polities before the 19th century as far north as the borders of Bornu and Mandara. According to the German explorer Heinrich Barth, who visited Adamawa in 1851, “it is their language [Batta] that the river has received the name Be-noë , or Be-nuwe, meaning ‘the Mother of Waters.’”3

The Adamawa plateau was mostly settled by the Mbum, who were related to the Jukun and Tchamba of the Benue valley and the Tikar of central Cameroon. They developed a well-structured social hierarchy with divine rulers (Bellaka) and exercised some hegemony over neighbouring groups.4

According to the historian Eldridge Mohammadou, some of these groups were at one time members of the succession of Kwararafa confederations, which were potent enough to sack the Hausa cities of Kano, Katsina, and Zaria multiple times during the 16th and 17th centuries, and even besiege Ngazagarmu, the capital of the Bornu empire, before their forces were ultimately driven out of the region.5

In the majority of the chieftaincies, a number of factors, such as kinship relations, language, religion, land, and the need for security, bound together the heterogeneous populations. Most chiefs were the political and religious heads of their communities; their authority was supported by religious sanctions. The polities had predominantly farming and herding economies, with marginal trade in cloth and ivory through the northern kingdoms of Bornu and Mandara.6

The political situation of the region changed dramatically at the turn of the 19th century following the arrival of Fulbe groups. The region settled by these Fulbe groups came to be known as Fombina, a Fulfulde term meaning ‘the southlands’.7

These groups, which had been present in the Hausalands and the empire of Bornu since the late Middle Ages, began their southward expansion in the 18th century. They mostly consisted of the Wollarbe/Wolarbe, Yillaga’en, Kiri’en, and Mbororo’en clans, who were mostly nomadic herders and the majority of whom remained non-Muslim until the early 19th century.8

Some of these groups also established state structures over pre-existing societies that would later be incorporated into the emirate of Adamawa. The Wollarbe, for example, were divided into several groups, each of which followed their leaders, known as the Arɗo. In 1870, the group under Arɗo Tayrou founded the town of Garoua in 1780 around settlements populated by the Fali, while around the same time, another group moved to the southeast to establish Boundang-Touroua around the settlements of the Bata.9

However, most of the Fulbe were subordinated to the authority of the numerous chieftains of the Fombina region, since acknowledgement of the autochthonous rulers was necessary to obtain grazing rights and security. Their position in the local social hierarchies varied, with some becoming full subjects in some societies, such as among the Higi and Marghi, while others were less welcome in societies such as the Batta of the Benue valley and the dependencies of the Mandara kingdom in northern Cameroon.10

The Sokoto Empire and the founding of Adamawa.

In the early 19th century, the political-religious movement of Uthman Dan Fodio, which preceded the establishment of the empire of Sokoto, and the expulsion of sections of the Fulbe from Bornu in 1807-1809 during the Sokoto-Bornu wars, resulted in an influx of Fulbe groups into Fombina. The latter then elected to send Modibo Adama, a scholar from the Yillaga lineage, to pledge their allegiance to the Sokoto Caliph/leader Uthman Fodio. In 1809, Modibo Adama returned with a standard from Uthman Fodio to establish what would become the largest emirate of the Sokoto Caliphate.11

Modibo Adama first established his capital at Gurin before moving it to Ribadou, Njoboli, and finally to Yola. As an appointed emir, he had defined duties and responsibilities over his officials, armed forces, tax collection, and obligations towards the Caliph, his political head and religious leader. His emirate, which was called Adamawa after its founder, eventually came to include over forty other units called lamidats (sub-emirates), each with its Lamido (chief) in his capital, and a group of officials similar to those in Yola.12

After initial resistance from established Fulbe groups, Modibo Adama managed to forge alliances with other forces, including among the non-Fulbe Batta and the Chamba. He raised a large force that engaged in a series of campaigns from 1811-1847 that managed to subsume the small polities of the region. The forces of Adamawa saw more success in the south against the chiefdoms of the Batta and the Tchamba in the Benue valley than in the north against the Kilba.13

In 1825, the Adamawa forces under Adama defeated the Mandara army and briefly captured the kingdom's capital, Dolo, but were less successful in their second battle in 1834. This demonstration of strength compelled more local rulers to submit to Adama's authority, which, together with further conquests against the Mbum in the south and east, created more sub-emirates and expanded the kingdom.14

In Cameroon, several Wollarɓe leaders received the permission of Modibo Adama to establish lamidats in the regions of Tibati (1829), Ngaoundéré (1830), and Banyo (1862). The majority of the subject population was made up of the Vouté/Wute, Mbum, and the Péré. Immigrant Kanuri scholars also made up part of the founding population of Ngaoundéré, besides the Fulbe elites. It was the Banyo cavalry that assisted the Bamum King Njoya in crushing a local rebellion.15

A group of lamidats was also established in the northernmost parts of Cameroon by another clan of Fulɓe, known as the Yillaga’en, who founded the lamidats of Bibèmi and Rey-Bouba, among others. The lamidat of Rey in particular is known for its strength and wealth, and for its opposition to incorporation into the emirate, resulting in two wars with the forces of Yola in 1836 and 1837.16

Entrance to the Palace at Rey, Cameroon. ca 1930-1940. Quai Branly.

Horsemen of Rey, Cameroon. ca. 1932. Quai Branly

‘Knights of the Lamido of Bibémi’ Cameroon, ca. 1933. Quai Branly.

an early 20th century illustration by a Bamum artist depicting the civil war of the late 19th century at Fumban and the alliance between Adamawa and Bamum to secure Njoya’s throne. (Musée d'ethnographie de Genève Inv. ETHAF 033558)

State and society in 19th-century Adamawa

By 1840, the dozens of sub-emirates had been established across the region. Modibbo Adama, as the man to whom command was delegated, played the role of the Shehu in the distribution of flags to his subordinates. While all the lamidats were constituent sub-states within the emirate of Adamawa, they were allowed a significant degree of local autonomy. Each ruler could declare war, arrange for peace, and enter into alliances with others without reference to Yola.17

Relations between Sokoto, Adamawa, and its sub-emirates began to take shape during the reign of Adama’s successor, Muhammad Lawal (r. 1847-1872). Contact with outside regions, which was hitherto limited, was followed by increased commerce with Bornu and Hausaland. Prospects for trade, settlement, and grazing attracted immigrant Fulbe, Hausa, and Kanuri traders into the emirate, further contributing to the region's dynamic social landscape.18

The borders of the Emirate were extended very considerably during the reign of Lawal, from the Lake Chad basin in the north, to Bouar in what is now the Central African Republic in the east, and as far west as the Hawal river. The emirate government of Fombina became more elaborate, and multiple offices were created in Yola to centralise its administration, with similar structures appearing in outlying sub-emirates.19

In many of the outlying sub-emirates, local allies acknowledged Adamawa’s suzerainity and thus retained their authority, such as in Tibati, Rey, Banyo, Marua, and Ngaoundéré. The local administration thus reflected the sub-emirate’s ethnic diversity, with two groups of councillors: one for the Fulbe and another for the autochthonous groups.20

In the city of Ngaoundéré, for example, the governing council (faada) was comprised of three bodies for each major community: the Kambari faada, for Hausa and Kanuri notables, the Fulani faada for Fulbe, and the Matchoube faada for the Mbum chiefs. The Mbum chiefs had established matrimonial alliances with the Fulbe and were allowed significant autonomy, especially in regions beyond the capital. Chieftains from other groups, such as the Gbaya and the Dìì, were also given command of the periphery provinces and armies, or appointed as officials to act as buffers between rivaling Fulbe aristocrats.21

Writing on the composition of the Yola government in the mid-19th century, the German explorer Heinrich Barth indicated that there was a Qadi, Modibbo Hassan, a ‘secretary of state’, Modibbo Abdullahi, and a commander of troops, Ardo Ghamawa. Other officials included the Kaigama, Sarkin Gobir, Magaji Adar, and Mai Konama. Despite the expansion of central authority, some of the more powerful local rulers retained their authority, especially the chiefs of Banyo, Koncha, Tibati, and Rey, but continued to pay tribute to the emir at Yola.22

Additionally, many of the powerful autochthons that had accepted the suzerainty of Adamawa and were allowed to retain internal autonomy resisted Lawal’s attempts at reducing them to vassalage. The Batta chieftains, including some of those living near the capital itself, took advantage of the mountainous terrain to repel the cavalry of the Fuble and even assert ownership of the surrounding plains. These and other rebellions compelled Lawal to establish ribats (fortified settlements) with garrisoned soldiers to protect the conquered territories.23

As Heinrich Barth observed while in Adamawa: “The Fúlbe certainly are always making steps towards subjugating the country, but they have still a great deal to do before they can regard themselves as the undisturbed possessors of the soil.” adding that “the territory is as yet far from being entirely subjected to the Mohammedan conquerors, who in general are only in possesion of detached settlements, while the intermediate country, particulary the more mountainous tracts, are still in the hands of the pagans.”24

This constant tension between the rulers at Yola, the semi-independent sub-emirates, the autochthonous chieftains, and the independent kingdoms at nearly all frontiers of Adamawa, meant that war was not uncommon in the emirate. Such conflicts, which were often driven by political concerns, ended with defeated groups being reduced to slavery or payment of tribute. Like in Sokoto, the slaves were employed in various roles, from powerful officials and soldiers to simple craftsmen and cultivators on estates (which Barth called ‘rumde’), where they worked along with other client groups and dependents.25

The influx of Hausa, Fulbe, and Kanuri merchant-scholars gradually altered the cultural practices of the societies in Fombina. The Hausa in particular earned the reputation of being the most travelled and versatile merchants in Adamawa. They are first mentioned in Barth's description of Adamawa but likely arrived in the region before the 19th century for various reasons. Some were mercenaries, others were malams (teachers), and others were traders.26

Writing board and dyed-cotton robe, 19th century, Adamawa, Cameroon. Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

The rulers at Yola encouraged scholars to migrate from the western provinces of Sokoto. Some served in the emirate's administration, while others founded towns that were populated with their students, eg, the town of Dinawo, which was founded in 1861 by the Tijanniya scholar and Mahdi claimant Modibbo Raji. The founding of mosques and schools meant that Islam and some of the cultural markers of Hausaland were adopted among some of the autochthons and even neighbouring kingdoms like Bamum, but most of the subject population retained their traditional belief systems.27

The diversity of the social makeup of Adamawa was invariably reflected in its hybridised architectural style, which displays multiple influences from different groups, and is the most enduring legacy of the kingdom.

The presence of walled towns, especially in northern Cameroon, is mentioned by Heinrich Barth, who notes that Rey-Bouba, alongside Tibati, was “the only walled town which the Fulbe found in the country; and it took them three months of continual fighting to get possession of it.”28 Walled towns were present in the southern end of the Lake Chad basin since the Neolithic period, and became a feature of urban architecture across the region from the Kotoko towns in northern Cameroon to the Hausa city states in northern Nigeria.

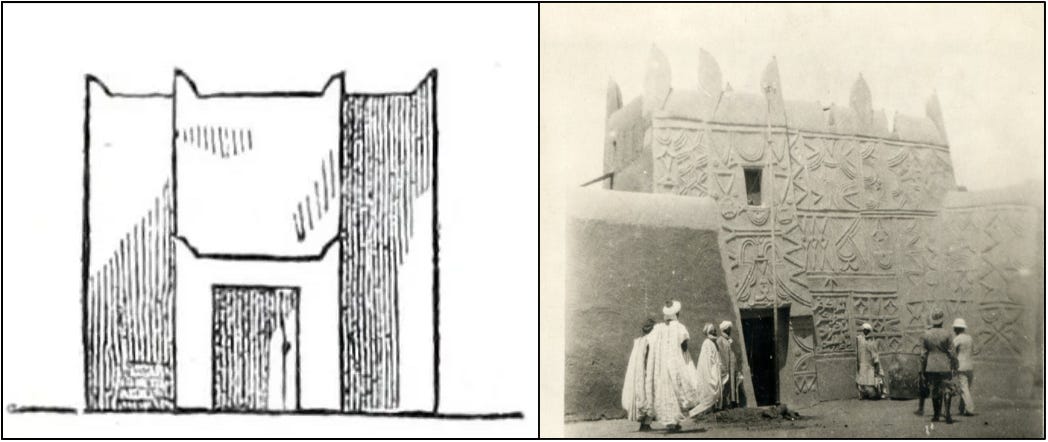

(left) Illustration of Lamido Muhammad Lawal’s palace at Yola by Heinrich Barth. (right) decorated facade of one of the entrances to the palace of Kano, Nigeria.

Barth’s account contains one of the earliest descriptions and drawings of the emir’s palace at Yola, and includes some of the distinctive features that are common across the region’s palatial architecture: “It has a stately, castle-like appearance, while inside, the hall was rather encroached upon by quadrangular pillars two feet in diameter, which supported the roof, about sixteen feet high, and consisting of a rather heavy entablature of poles in order to withstand the violence of the rains.”29

The historian Mark DeLancey’s study of the palace architecture of Adamawa’s subemirates in Cameroon shows how the different features of elite buildings in the region reflected not just Fulbe construction elements, but also influences from the building styles of the autochtonous Mbum, Dìì, and Péré communities, which were inturn adopted from Hausa and Kanuri architectural forms.30

The distinctive style of architecture found in the Hausa city states, which was adopted by the Fulbe elites of Sokoto and spread across the empire, had been present in Fomboni among some non-Fulbe groups, such as the Dìì and Mbum of the Adamawa plateau, as well as among early Fulbe arrivals before the establishment of Adamawa. 31

A particularly notable feature in Fomboni’s palatial architecture was the sooro —a Hausa/Kanuri word for “a rectangular clay-built house, whether with flat or vaulted roof.” These palaces are typically walled or fenced and have monumental entrances, opening into a series of interior courtyards, halls, and rooms. The ceiling of the sooro is usually supported from within by earthen pillars with a series of arches or wooden beams, and the interior is often adorned with relief sculptures.32

(left) Vaulting in the palace throne room, built in the early 1920s by Mohamadou Maiguini at Banyo, Cameroon. Image by Virginia H. DeLancey. (right) Vaulted ceiling of the palace at Kano, Nigeria.

construction of Hausa vaults in Tahoua, Niger, ca. 1928. ANOM

Vestibule (sifakaré) of the Lamido’s palace at Garoua, Cameroon. ca 1932. Quai Branly museum.

Palace entrance in Kontcha, Cameroon. Image by Eldridge Mohammadou, ca. 1972

Entrance to the Sultan's Palace at Rey, Cameroon, ca. 1955. Quai Branly

(left) Gate within the palace at Rey, Cameroon. ca. 1932. Quai Branly. (right) interior of the palace at Garoua, Cameroon. ca. 1932. Quai Branly.

(left) Interior of Jawleeru Yonnde at Ngaoundéré, Cameroon, ca. 1897–1901. National Museum of African Art, Washington, D.C. (right) Plan and interior of the palace entrance at Tignère, Cameroon, ca. 1920s–1930s.

The sooro quickly became an architectural signifier of political power and a prominent mark of power, and as such was the prerogative of only the caliph and the emirs. The construction of a large and majestic sooro at the entrance to the palace at Rey, for example, preceded the establishment of the Sokoto Caliphate by 5 years and declared Bouba Ndjidda’s independent status in that land on the eastern periphery of the Fulɓe world.33

While many of the palaces were destroyed during the colonial invasion, the region’s unique architectural style remained popular among local elites well into the colonial period.

Decline, collapse, and the effects of colonialism in Adamawa.

Lawal was succeeded by the Lamido Umaru Sanda (r. 1872-1890), during whose relatively weak reign rebellions by the sub-emirates continued unabated, and some non-Fulbe peoples seized the opportunity to become independent. In the Benue valley, some of the more powerful chiefs among the Batta and Tengelen threw off their allegiance and began to attack ivory caravans. An expedition sent against the Tengelen in 1885 was defeated, underscoring the weakness of the Adamawa forces at the time, which often deserted during battle.34

The expansion of European commercial interests on the Benue during the late 1880s was initially checked by Sanda, who often banned their ivory trade despite directives from Sokoto to open up the region for trade. Sanda ultimately allowed the establishment of two trading posts of The Royal Niger Company at Ribago and Garua, but none were allowed at the capital Yola.35

Sanda was succeeded by the Lamido Zubairu (r. 1890-1903,) who inherited all the challenges of his predecessor, including internal rebellions —the largest of which was in 1892, led by the Mahdist claimant Hayat, who was allied with the warlord Rabih. Zubairu's forces were equally less successful against the non-Fulbe subjects, who also rebelled against Yola, and his forces failed to reconquer the Mundang and Margi of the Bazza area on the Nigeria/Cameroon border region.36

In the 1890s, Yola became the focus of colonial rivalry between the British, French, and Germans during the colonial scramble as each sought to partition the empire of Sokoto before formally occupying it.37

Zubairu initially played off each side in order to acquire firearms, but the aggressive expansion of the Germans in Kamerun forced the southern emirates to adopt a more hostile stance towards the Germans, who promptly sacked Tibati and Ngaoundéré in 1899 and took control of the eastern sub-emirates.38

While the defeat of Rabih by the French in 1900 removed Zubairu's main rival, it left him as the only African ruler surrounded by the three colonial powers. Lord Lugard, who took over the activities of the Royal Niger company that same year, sent an expedition to Yola in 1901 which captured the capital and burned its main buildings despite stiff resistance from Zubairu’s riflemen. Zubairu fled the capital and briefly led a guerrilla campaign against the colonialists but ultimately died in 1903, after which the emirate was formally partitioned between colonial Nigeria and Cameroon.39

‘The final assault and capture of the palace and mosque at Yola.’ Lithograph by Henry Charles Seppings Wright, ca. 1901.

After the demarcation of the Anglo-German boundary, 7/8th of the Adamawa emirate fell on the German side of the colonial boundary in what is today Cameroon. The boundary line between the British and German possessions did not follow the boundaries of the sub-emirates, some of which were also divided. In some extreme cases, such as the metropolis of Yola itself, only the capitals remained under their rulers while the towns and villages were separated from their farmlands and grazing grounds.40

While it’s often asserted that the colonial partition of Africa separated communities that were previously bound by their ethnic identity, the case of Adamawa and similar pre-colonial states shows that such partition was between heterogeneous communities with a shared political history. This separation profoundly altered the political and social interactions between the various sub-emirates and would play a significant role in shaping the history of modern Cameroon.41

North Cameroon, Ngaounderé Horsemen of the Sultan of Rey Bouba. mid-20th century.

My latest Patreon article explores the history of the Sanussiya order of the Central Sahara, which developed into a vast pan-african anti-colonial resistance that sustained the independence of this region until the end of the First World War.

Please subscribe to read more about it here.

Modified by author based on the map of the Sokoto caliphate by Paul. E. Lovejoy and a map of Adamawa’s principal districts and tribes by MZ Njeuma

The Rise and Fall of Fulani Rule in Adamawa, 1809-1901 by MZ Njeuma, pg 37-38

The Rise and Fall of Fulani Rule in Adamawa, 1809-1901 by MZ Njeuma, pg 34-36, Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa, Volume 1 by Heinrich Barth, pg 473

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 1, 5-20, Fulani Hegemony in Yola (Old Adamawa) 1809-1902 By M. Z. Njeuma, pg 25

Conquest and Construction: Palace Architecture in Northern Cameroon By Mark DeLancey, pg 17

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 20-23

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg pg 5

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 30-32, 36-39, on Islam among the Adamawa Fulani: The Rise and Fall of Fulani Rule in Adamawa, 1809-1901 by MZ Njeuma, pg 55-57

Conquest and Construction: Palace Architecture in Northern Cameroon By Mark DeLancey, pg 11

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 39-42, The Rise and Fall of Fulani Rule in Adamawa, 1809-1901 by MZ Njeuma, pg 40-43

Fulani Hegemony in Yola (Old Adamawa) 1809-1902 By M. Z. Njeuma, pg 5-12, The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 43-49

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 2-3, 50-51

Fulani Hegemony in Yola (Old Adamawa) 1809-1902 By M. Z. Njeuma, pg 14-15, The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 56-62)

Fulani Hegemony in Yola (Old Adamawa) 1809-1902 By M. Z. Njeuma, pg 19- 24, The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 64-69

Conquest and Construction: Palace Architecture in Northern Cameroon By Mark DeLancey pg 13-14, Fulani Hegemony in Yola (Old Adamawa) 1809-1902 By M. Z. Njeuma, pg 36-38, War, Power and Society in the Fulanese “Lamidats” of Northern Cameroon: the case of Ngaoundéré in the 19th century by Theodore Takou pg 93-106

Fulani Hegemony in Yola (Old Adamawa) 1809-1902 By M. Z. Njeuma, pg 58

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 75-79

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 90-95

The Rise and Fall of Fulani Rule in Adamawa, 1809-1901 by MZ Njeuma, pg 157-240

The Rise and Fall of Fulani Rule in Adamawa, 1809-1901 by MZ Njeuma, pg 243-244

War, Power and Society in the Fulanese “Lamidats” of Northern Cameroon: the case of Ngaoundéré in the 19th century by Theodore Takou pg 93-106

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 96-100

Fulani Hegemony in Yola (Old Adamawa) 1809-1902 By M. Z. Njeuma pg 37-41,

Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa, Volume 1 By Heinrich Barth, pg 430, 469

Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa, Volume 1 By Heinrich Barth, pg 458, 469

The Rise and Fall of Fulani Rule in Adamawa, 1809-1901 by MZ Njeuma, pg 306-309)

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 105-109

Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa, Volume 1 by Heinrich Barth, pg 472

Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa, Volume 1 by Heinrich Barth, pg 463

Conquest and Construction: Palace Architecture in Northern Cameroon By Mark DeLancey 19-20, 34-64

Conquest and Construction: Palace Architecture in Northern Cameroon By Mark DeLancey pg 72

Conquest and Construction: Palace Architecture in Northern Cameroon By Mark DeLancey, pg 66-91)

Conquest and Construction: Palace Architecture in Northern Cameroon By Mark DeLancey, pg 75

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 124-126

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 134-135

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 135-138

The Rise and Fall of Fulani Rule in Adamawa, 1809-1901 by MZ Njeuma, pg 317-320

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 139-144, The Rise and Fall of Fulani Rule in Adamawa, 1809-1901 by MZ Njeuma, pg 321-423

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 145-148, The Rise and Fall of Fulani Rule in Adamawa, 1809-1901 by MZ Njeuma, pg 424-460

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 154

Conquest and Construction: Palace Architecture in Northern Cameroon By Mark DeLancey, pg 79-100, Regional Balance and National Integration in Cameroon: Lessons Learned and the Uncertain Future by Paul Nchoji Nkwi, Francis B. Nyamnjoh

A very interesting perspective. Thank you for this article!

I’m a Cameroonian diasporan and my research about my tribe has led me to this article. Thank you for taking up the burden of such great tasks as this. 🙏🏾