Taming and domesticating the wild: the War-Elephants of ancient Aksum and Kush

In his 1668 description of the West African kingdom of Benin, the Dutch writer Olfert Dapper reported that “The king shows himself only once a year to his people, going out of his court on horseback, accompanied by three or four hundred noblemen on horseback.” He also mentions that “the king causes some tame leopards that he keeps for his pleasure to be led out in chains” a scene which Dapper includes in his famous engraving of Benin city.1

While Dapper’s description of Benin may initially appear to be a typical embellished account about a distant African kingdom that is intended to thrill armchair adventurers back in Europe, there is sufficient historical evidence for the taming of wild animals like leopards, lions, and elephants in several African societies, including in Benin, where tame leopards were kept alongside domesticated animals like horses, because they were considered to be symbols of the king’s authority.2

Detail of the 17th century engraving depicting the leopards of the king of Benin.

16th-century relief plaques depicting the Oba holding two leopards by the tail, and a leopard feeding her cubs. Af1898,0115.31 British Museum, III C 27486, Ethnologisches Museum Berlin.

Two centuries before Dapper's description of Benin, an embassy from Ethiopia reached the Italian city of Venice in 1402, where they cruised the city's canals accompanied by four live leopards.3 Later visitors to Ethiopia in 1515 and 1765 mention the presence of chained lions that accompanied the emperor's entourage,4 and that a number of the richer citizens of its capital, Gondar, were in “the habit of keeping tame lions which were on occasion taken out for walks in the streets.”5 By 1770, a lion's cage was constructed among the castellated palaces of the city that would house tame lions until 1965.6

‘Anbesa Bet’ (Lion cages) in Gondar, Ethiopia, image by H. Sinica.

The Ethiopian monarch Menelik II, and Ethiopian nobles with tame lions. Photos from the early 20th century.

While Africa's famous animals such as Zebras, Lions, and Rhinos were impossible to domesticate —something that geographic determinists have been wont to emphasize. This wasn't due to lack of trying by Africans [nor by European settlers in South Africa who also failed to domesticate them, declaring that “the zebra is said to be wholly beyond the government of man”.7] After all, Africans did successfully domesticate cattle and donkeys,8 alongside ‘foreign’ domesticates like horses, which were quickly adopted across the continent from West Africa to East and Southern Africa, where they diverged into multiple local breeds.

The African horses and donkeys which carried soldiers to battle, trade-goods to distant cities, and Kings in royal processions became veritable symbols of military and political power across multiple societies.

Contrary to the claims of Jared Diamond and his ilk, Africans didn't need “Rhino-mounted shock troops” to cut through the ranks of Roman horsemen, because the horse-mounted troops of Kush's Queen Amanirenas did just fine when they defeated the Roman invasion in 20BC, and even those that lacked horses, such as the kingdom of Ndongo, repeatedly defeated Portuguese horsemen in battle.

a rider rearing his horse in Dikwa, Nigeria. early 20th century Photo.

Besides these domesticates, Africans also tamed wild animals and included them in their iconographic corpus of royal artwork, representing the centrality of particular animals to their cosmological systems and concepts of political power.

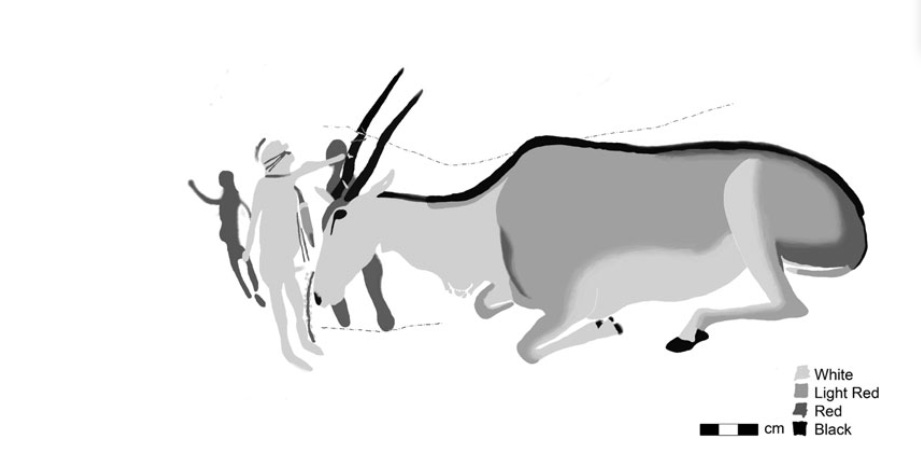

The eland, for example, is central to the cosmology of the San in southwest Africa and appears extensively in their rock art. Rock paintings of human figures stroking, leading, or enticing the animals with plant ‘charms,’ which were partly based on real actions of the San, all powerfully evoke superlative spiritual control of these creatures; while renditions of animals lying down or standing calmly among human figures strongly recall the ‘tamed’ state of resources influenced by ritual specialists.9

The taming of wild animals was also prevalent in the ideology of power in the East African kingdom of Buganda where animals such as the lion and buffalo were considered symbols of Kingly authority. In the 1850s for example, the Ganda King Ssuuna II (r. 1832-1856) kept a “menagerie of lions, elephants, leopards and similar beasts of disport” which were captured during royal hunts.10

Drawing of a cave-painting from the eastern Cape province in South Africa, depicting a human figure reaching out his hand toward a ‘calm’ eland.11

In many of these examples, tame animals were kept for symbolic functions, they weren’t ridden into battle like horses, nor did they carry trade goods like donkeys. Its from the ancient kingdoms of Aksum and Kush that we obtain documentary and artistic evidence for the taming and utilization of the elephant, which not only had a symbolic function but also carried warriors to battle.

Virtually all classical accounts give prominence to elephants from the kingdoms of Aksum and Kush, which supplied the famous war elephants of the Ptolemies during the 3rd century BC, and continued to feature in the military systems and artistic traditions of Kush and Aksum. War elephants appear extensively in the royal iconography of Kush, especially at the temple of Mussawarat, and in Aksum, where elephant corps were included in the regiments of King Ezana and were famously used by the Aksumite general Abraha during his campaigns in Arabia.

The history of the war elephants of Aksum and Kush is the subject of my latest Patreon article,

Please subscribe to read about it here:

Wall terminal in the shape of an elephant at Musawwarat es Sufra, Sudan.

Royal Art of Benin: The Perls Collection in the Metropolitan Museum of Art By Kate Ezra pg 117

Royal Art of Benin: The Perls Collection in the Metropolitan Museum of Art By Kate Ezra pg 156.

The African Prester John and the Birth of Ethiopian-European Relations By Matteo Salvadore pg 24-25

The Prester John of the Indies: A True Relation of the Lands of the Prester John, Being the Narrative of the Portuguese Embassy to Ethiopia in 1520 by Francisco Alvares pg 324, 337, 442)

History of Ethiopian Towns from the Middle Ages to the Early Nineteenth Century, Volume 1, Richard Pankhurst pg 170

(tame lions were also present in the Funj kingdom of Sennar according to James Bruce) Travels between the Years 1765 and 1773 by James Bruce pg 235, Ethiopia: History, Culture and Challenges edited by Siegbert Uhlig pg 325

Riding High: Horses, Humans and History in South Africa by Sandra Scott Swart pg 24-26, examples of Europeans taming, but not domesticating quaggas: The Life, Extinction, and Rebreeding of Quagga Zebras By Peter Heywood pg 68-79

Domesticating Animals in Africa: Implications of Genetic and Archaeological Findings by Diane Gifford-Gonzalez

Reconfiguring Hunting Magic: Southern Bushman (San) Perspectives on Taming and Their Implications for Understanding Rock Art, Rock paintings which may depict live eland being used in San rites by Pieter Jolly.

Political power in Pre-colonial Buganda by Richard J. Reid pg 55-57

Reconfiguring Hunting Magic: Southern Bushman (San) Perspectives on Taming and Their Implications for Understanding Rock Art 585.

It’s strange that Egypt is the primary African kingdom taught in western schools. Many of the kingdoms in Africa that you write about are equally as fascinating and grand. I did do a class project on Mali, in elementary school, as we all picked an African country to research.

However, that would be about the extent of it, as more focus was on South America, the Middle East, China, and obviously Europe. I wish I had learned much of this earlier.

Someone was challenging the use of Roman Cavalry during the invasion of Kush, said there isn't' any source for that, he's also skeptical of the use of horses by the folks of the central African states against the Portguese.