The indigenous versus foreign origins of West Africa’s pre-colonial architecture.

Architecture is an aspect of culture that mediates between man and his environment, and it has been one of the first of the arts to adopt new materials and techniques.

While previous research on West African architecture often stressed the foreign influences of its more complex forms, recent studies have shown that West African construction styles were products of endogenous developments and internal processes unique to the region.

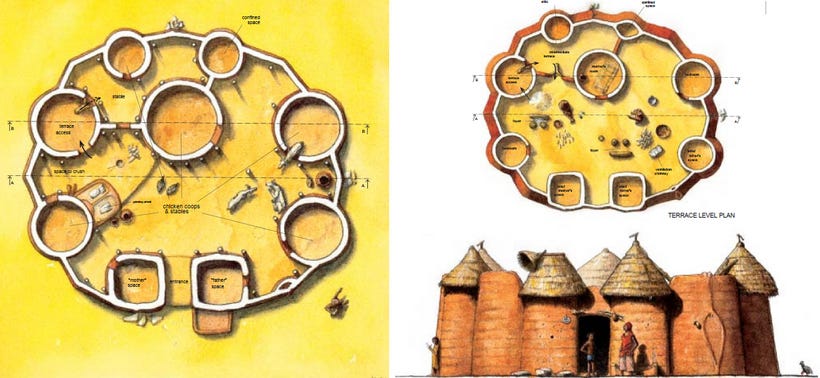

For example, the basic form of a compound found among Mande-speakers in the west African savannah, which consists of a large central courtyard and multiple interlocking houses surrounded by a high wall1, was developed in the Neolithic traditions of the Tichitt and Mema regions between the 2nd to 1st millennium BC.

According to the archaeologist Kevin MacDonald:

“The potential influence of pre-Islamic North African architectural forms on the Sahel has had a long currency. Prussin, for example, asserts a Roman origin for the Berber ‘courtyard house’ or fortified farms, seen as leading to subsequent allied Islamic forms in the Sahel. Indeed, were it not for the ample and early architecture of the Tichitt Tradition an argument could have been advanced for a primarily North African role in the creation of the West African compound.”2

In the early 1st millennium CE, the main material used in the architecture of the West African savannah was mudbricks of both curvilinear and rectangular form. Both types of bricks were found at the Malian sites of Dia-shoma (dated 9BC–67 CE), Akumbu (5th century CE), Mouyssam II (340-690 CE), Tongo Maaré Diabel (650-750 CE), and Gao-Saney (700CE).3

Bricks drying in the sun. ca. 1931, Djenne, Mali. Quai Branly.

While Shoichiro Takezawa, one of the excavators of Gao-Saney, asserts that rectangular mudbricks were unknown in the rest of medieval West Africa and could only have been introduced by North Africans4, the discovery of multiple pre-Islamic sites with such bricks led MacDonald to conclude that their early use in west African construction “disassociates Islamic trade from the first appearances of early Sahelian (loaf-shaped) mudbrick.”5

By the late Middle Ages, West African masons were able to construct large monuments using local materials and techniques, featuring all the hallmarks of the region's architecture, including storied structures with thick buttresses and flat roofs supported by massive pillars.

Palace of the Senufu king Gbon Coulibaly at Korhogo, Cote d'Ivoire, ca. 1926, Quai Branly.

Palace of the ruler of Palacca, north of Korhogo, Côte d'Ivoire. ca. 1927, ANOM.

In the Hausalands, a similar architectural tradition emerged based on mudbrick technology, whose defining features were its distinctive pinnacles on flat roofs, vaulted domes, and profusely decorated walls.

Interior and exterior of the 19th-century mosque of Zaria, Nigeria.

Many of these monuments had an orthogonal (rectangular) layout, which is often impressionistically attributed to the concurrent spread of Islam in medieval West Africa. However, past research had already shown that this claim is contradicted by the evidence from the architectural styles of non-Muslim West African societies.

According to Prussin:

“The Sudanese style [of architecture], exemplified by its towering , rhythmic , buttress-like pillars and rectangular forms, has always been associated with the introduction of Islam. But upon closer scrutiny it has been found that many Islamized peoples have, in fact, adopted neither rectangular forms nor Sudanese style. Again, the rectangular terrace style exists among peoples where Islam has made absolutely no inroads , and finally, among many peoples one finds the circle and the square interspersed not only in the same village but in the same compound.”6

Circular and rectangular structures in the Royal Court of Tiébélé, a non-Muslim society in Burkina Faso.

Circular and rectangular structures in the ‘castle’ houses of northern Benin and Togo.

The presence of rectangular monuments among non-Muslim West African societies is indeed fairly common and is of significant antiquity. The ruined sites of Loropeni, Obire, Karankasso, and Lakar on the border region of Ghana/Burkina-Faso, which are dated to the early 2nd millennium CE, feature multiple types of rectilinear stone structures and walls, but contain little Islamic material.

Partial view of a structure (Lor-sat 27) of Loropéni exposed in its northern and southern parts. Image by H. Farma.

MacDonald also identified a number of rectilinear structures at a much older site of T150 in the Tagant section of the Tichitt Neolithic tradition, which emerged during its late phase, dated to between (c.150 BC–70 CE).7 He suggests that the development of this form was linked to the concurrent appearance of rectilinear structures at the Garamantian site of Fewet in southern Libya, despite the two regions being separated by more than 2,000 miles and little evidence for long-distance contacts at any of the Tichitt sites.

ruined structure with an orthogonal layout in the agglomeration of Dakhlet el Atrouss I. Image by R. Vernet

A stronger argument could be made for the independent development of rectilinear constructions in West Africa based on the presence of such structures in the Kintampo Neolithic tradition of Ghana (ca. 1900-1200BC). In this region, houses with square and rectangular layouts were built with wattle and daub, coated with plaster, and lined with stones.

Many of the earliest accounts of the architecture of Ghana describe houses that were still built in this ancient style, featuring rectilinear structures with plastered walls of wattle-and-daub construction.

This form of construction was especially common in the Asante kingdom, whose distinctive style of ornamented architecture is one of the most celebrated among the non-Muslim societies of West Africa

My latest Patreon article explores the history of Asante's architecture, outlining its origins and its development from the 17th to the 20th centuries.

n

Mande Studies, Volume 2, African Studies Program, University of Wisconsin, 2000, pg 118, Architecture, Islam, and Identity in West Africa: Lessons from Larabanga By Michelle Apotsos, pg 80

Urbanisation and State Formation in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond edited by Martin Sterry, David J. Mattingly pg 500

Urbanisation and State Formation in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond edited by Martin Sterry, David J. Mattingly pg 505-506

Discovery of the earliest royal palace in Gao and its implications for the history of West Africa by Shoichiro Takezawa and Mamadou Cisse, pg 7-8, 11, 24, n10 25 n16

Takezawa interprets the site as a North-African colony, contradicting his co-author's publication on the same (see; Archaeological Investigations of Early Trade and Urbanism at Gao Saney by M. Cisse). The main evidence he provides for this is the shape of the bricks and the imported material at the site. For the rectangular-shaped bricks, he cites Prussin’s argument that these bricks had Arabic names, and only mentions the west African sites of Djenne-Jenno, Tegdaoust, and Kumbi Saleh, but was apparently unaware of the pre-Islamic sites listed by MacDonald.

Urbanisation and State Formation in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond edited by Martin Sterry, David J. Mattingly pg 509-510

African Arts: Arts D'Afrique, Volume 3, Issue 4, African Studies Center, University of California, Los Angeles, 1970, pg 13.

Urbanisation and State Formation in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond edited by Martin Sterry, David J. Mattingly pg 503-504

Hi Isaac I have question regarding the image of the Palace of the ruler of Palacca. What is Palacca? Since it says it is in Korhogo and the town already had Gbon Coulibaly as ruler im a bit confused. Did they have two rulers or maybe Palacca is another town and Korgohogo is the province?