A complete history of the Sudano-Sahelian architecture of west Africa: from antiquity to the 20th century

The westernmost region of Africa which forms the watershed of the great rivers of the Senegal, the Volta and the Niger, is home to one of the world's oldest surviving building traditions, called the ‘Sudano-Sahelian’ architecture.

Characterised by the use of bricks and timber, the Sudano-Sahelian architecture encompasses a wide range of building typologies. It features the use of buttressing, pinnacles and attached pillars, with a distinctive façade that is punctuated by wooden spikes and is often heavily ornamented with intricate carvings.

Many of the monuments constructed in this style, including Palaces, Mosques, and Fortresses, are vibrant works of art with their own distinct aesthetics. These structures captured the imagination of visitors to the region during the pre-colonial period, and became the hallmark of west-African architecture during the colonial and post-independence periods.

This article outlines the history of Sudano-Sahelian architecture from its foundations in antiquity, and includes many examples of some of the most notable historical monuments of west Africa.

Map showing the empires of pre-colonial west Africa

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more on African history and to keep this blog free for all:

The earliest west African building traditions: from Neolithic Tichitt to Jenne-jeno.

The earliest forms of West African architecture are to be found in the sandstone escarpments of Tichitt-Oualata in southeastern Mauritania, where a neolithic tradition emerged around 2200BC, marked by proto-urban drystone masonry settlements associated with burial monuments. During the classic Tichitt period, sites expanded westwards towards Dhar Tagant, southwards towards the Méma region of Mali, and further east to the Lakes region of Mali, where compounds constructed of drystone masonry and funeral pillars dating from this period have also been documented.1

In the core of the Tichitt Tradition monumental funerary landscapes, the site of Dakhlet el Atrouss I (80 ha) became the main regional center of a multi-tiered settlement hierarchy. This proto-urban settlement is centered around two massive funerary monuments and features 540 stone-walled compounds with stone pillars, several homes, and cattle enclosures separated by pathways and massive walls. It is arranged in 26 compound clusters, perhaps relating to lineage quarters, with some large outlying walled areas. Its material culture indicates that it was occupied by proto-Soninke speakers.2

Walled compounds of Akreijit, a Tichitt regional center in Mauritania.

Views of three parts of the agglomeration of Dakhlet el Atrouss I. image by R. Vernet.

One of the two funerary monuments of Dakhlet el Atrouss 1, east of Akreijit. Image by R. Vernet.

Around 900 BC, a broad settlement transformation took place in the Mema region of Mali, as the pre-existing ephemeral camps were displaced by more permanent settlements with cereal agriculture.

These settlements begun at 10 ha site of Kolima Sud-Est, the 18ha site of Dia Shoma between 900-400BC, and the later site of Jenne-Jeno in the 3rd century BC. They all contain Tichitt-style pottery (called the Faıta Facies) in their earliest settlement phases, indicating a direct transfer/expansion of the Tichitt population to Mema. However, these settlements feature earthen architecture rather than dry-stone*, since the Mema region was (and remains) a floodplain, without native stone resources comparable to those of the Tichitt escarpment.3

(*dry-stone architecture continued in southern Mauritania during the medieval period)

This earthen architecture became especially prevalent during the Jenné-jeno Phase III (400–900 CE), when houses were built with distinctive cylindrical sundried mud-bricks called djeney-ferey, as well as its city wall. A recently discovered site of Tongo Maaré Diabal in Mali, a small nucleated settlement first occupied around 500CE and located about 250km northeast of Jenne-Jeno, contained the remains of curvilinear and rectilinear mud-brick structures built with ‘loaf-shaped’ rectangular bricks in its Horizon 2 phase (650-750CE).4

Rectilinear structures with drain pipes indicating a flat roof, possibly with an upper story, were constructed by the 11th century at both Jenne-jeno Phase IV (900-1400 CE) and Dia Horizon IV (1000 -1600 CE) where a city wall also appears during this period. Rectangular fired bricks used for reinforcement or for decorative effects appear in this phase at Jenne-jeno, while rectangular sun-dried bricks also appear at Dia during the same period.5

Houses from both Jenne-Jeno and Dia during this period also include bedrests, attached ovens, as well as indoor bathing areas and latrines drained by long ceramic pipes. These houses at Jenne-jeno in particular contained many of Djenne’s iconic terracotta statuettes in wall niches, floors and shrines; the latter of which had pottery with serpentine imagery. More presence of domestic activity is indicated by spindle whorls and other material culture from earlier phases such as pottery and iron objects.6

Excavated house at Unit C, Dia-Shoma (Horizon IV), showing rectilinear rooms and loaf shaped mud bricks visible in the wall section. image by N. Arazi.

(Left) Mudbrick walls and drainage pipe at Unit C, Dia-Shoma, (Horizon IV), (right) Narrow streets of Dia flanked by compound walls and rectilinear mudbrick houses associated with drainage pipes. images by N. Arazi

Multiple pathways to west Africa’s architectural history.

While the evolution of West African architecture from Tichitt to Jenne-Jeno and Dia can be traced with some certainty, the emergence of several nucleated settlements across West Africa from similarly old neolithic traditions complicates this seemingly linear sequence, as the example of Tongo Maaré Diabal shows. This singular chronological trajectory presupposes an exhaustive census of all the archeological sites and architectural monuments of the region in order to relate their various construction styles and inscribe each monument in time and space. However, such theoretical formulations are contradicted by other archeological discoveries.

For example, the Neolithic tradition that emerged near the Bandiagra cliffs of Mali at the site of Ounjougou, was also based on the cultivation of pearl millet like Tichitt and contains the ruins of walled compounds of drystone masonry dated 1900-1800 BC.7 Similary, the remains of rectangular houses measuring 7x3m and constructed with stone and daub, were discovered at multiple sites of the Kintampo neolithic culture (ca. 1900-1200BC) in northern Ghana, at the sites of Ntereso, Boyasi, Bonoase, and Mumute.8

These two traditions are both contemporary with Tichitt and thus point to multiple origins of West Africa's architectural styles from vastly different ecological zones.

By the early 2nd millennium CE, mud-brick architecture is attested at several sites in the Bandiagara escarpments and surrounding valley during the so-called ‘Tellem period’, alongside much older structures made with coiled clay, some of which had orthogonal layouts and flat roofs and were part of an agglomerated compound.9 To the east of the Bandiagara cliffs, the recent excavations in the Niger Bend region at Kissi, Gao and Oursi, have also revealed a distinctive cultural tradition that was only tangentially linked to the sites of Jenne and Dia, with elite monuments that slightly predated those found at the latter sites.

‘Tellem’ constructions of coiled clay and stone at Yougo Dogorou, Bandiagara, Mali.

Dogon constructions in the escarpment and surrounding plains of Bandiagara.

The monumental architecture of the pre-Islamic west Africa:

Gao

The settlement at Gao emerged during the second half of the 1st millennium CE, with occupation at the largest sites at Gao-Saney and Gao Ancien dated to 700-1050CE.10Like at jenne-jeno and Dia, the main building material at Gao were mud-bricks, but most were rectangular* unlike those at the former sites. Gao Ancien contains the remains of numerous building constructions (foundations, columns and floors) built in dry-stone walling, mud brick and fired brick from the 9th-13th cent, with rectlinear houses from around 700CE.11

(*Gao isn’t the oldest site with rectangular mudbricks or rectilinear structures, but Tongo Maaré Diabal)

Its at Gao Saney that we find two of the earliest identifiable Palaces in west Africa. These two structures, refered to as the 'Long House' and the 'Pillar House' were constructed around 900CE century and abandoned by 1100CE, based on radiocarbon dates obtained from both sites. The Long house is built in laterite and schist dry stone-walling, fired brick and mud brick, it has long narrow rectangular paved rooms and a monumental decorative gateway, indicating that it was an elite residence. The Pillar house was constructed using the same material, it features a central room with eight circular stone pillars, and its house floor was painted in red ochre and white lime powder.12

The material culture of Gao indicates that it was occupied by a mostly local population of sedentary farmers, and all dated material indicates that it was abandoned by 1050CE, well before the appearence of the first Muslim ruler whose name is inscribed on the stele found in the cemetary of Gao-saney ca. 1088 CE. The polychrome pottery found at Gao is associated with the Songhai-speaking populations of the Niger Bend extending from Timbuktu to Bentiya. The pottery of the 1st millenium CE site of Oursi in particular, presents clear possibilities for regional antecedants of the Gao Saney assemblage.13

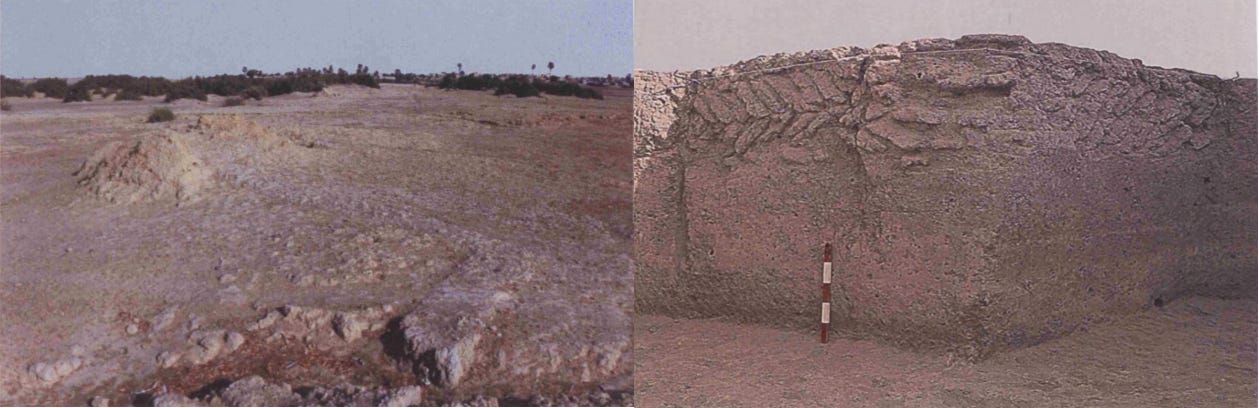

Ruins of the ‘Pillar House’ and the ‘Long House’ at Gao Ancien, constructed around 900 CE. Images by M. Cisse.

Bathroom of the small building in the pillar house at Gao-saney. image by Takezawa and Cisse

Plan of the buildings at Gao-Ancien. Takezawa and Cisse.

Oursi

The archaeological site of Oursi in north-eastern Burkina Faso is one of several pre-Islamic sites in the Niger-Bend region that contains early evidence for nucleated settlements in west Africa, with permanent occupation dating back to the late 1st millenium BC.14

The site is dominated by the remains of a massive house complex called Oursi Hu-Beero, which was constructed between 1020 and 1070CE, according to dated material recovered from its interior. The house complex consists of 28 clustered rooms constructed in four phases with sun-dried rectangular mudbricks with a building size about 300m2. The units are not free-standing but are built adjacent to one another, sharing enclosing walls and separated by intermediate walls, and include both curvilinear and rectangular rooms.15

The ruins of Oursi Hu-beero and the shelter built to protect them.

the massive square pillars of room 18, measuring about 1m on each side. images by Lucas Pieter Petit et al.

Layout of the Oursi House showing the walls and pillars (red) and the rooms (black). Room 20 is rectangular, its delimited by a wall (16) and three pillars (51, 52, 53).

The house had an upper storey supported by seventeen rectangular mudbrick pillars, sitting ontop of a roof made of wooden timbers. The upper floor was covered by a clay roof, and it was used for most domestic activities as indicated by the roof debris, which included weapons, copper bracelets, beads, and other jewellery, and grinding stones. The building complex and surrounding sites made up a village that was occupied by a few hundred people, estimates vary from 200 to 800 persons.13

Reconstruction of Oursi Hu-beero by Lucas Pieter Petit et al.

Loropeni and the Lobi ruins.

As mentioned above, the region of northern Ghana was for long home to multiple sedentary societies with nucleated settlements and distinctive architectural styles since the 2nd millenium BC, many of which included the remains of rectangular houses of stone and daub.

Much larger elite monuments with orthogonal (rectangular) layouts have also been at discovered in the 'Lobi ruins'; a 120-mile-by-60-mile cultural landscape spanning lands that cross the modern borders of Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Ghana. It contains hundreds of sites, the largest of which are about a dozen walled settlements, mostly in Burkina Faso such as Loropeni, Obire, Karankasso, and Lakar. Their walls and the houses they enclosed were built with laterite stone and earth, with the earliest dates ranging from; 1040-1420CE.16

(left) Plans of enclosures at same approximate scale. Loropéni, Karankasso, 1km west of Obiré, Obiré village, Obiré ouest, Lakar, Olongo, Yérifoula and Loghi. Image by Henry Hurst. (right) Aerial view of Loropeni, east side.

Partial view of a structure (Lor-sat 27) of Loropéni exposed in its northern and southern parts. Image by H. Farma.

Old Buipe.

Excavations at the 15th century site of Old Buipe in northern Ghana, have uncovered the ruins of several large multiroomed courtyard houses with an orthogonal design, and flat roofs —some of which had an upper storey. The largest structures were located in Fields; A, C and D, with a complex plan of juxtaposed rectangular rooms and courtyards, plastered cob walls (these are built with hardened silt, clay and gravel rather than brick), laterite floors, and a flat terrace-roof.17

These finds indicate that the site was relatively large urban settlement of significant political importance prior to the emergence of the kingdom of Gonja, which was purpotedly founded by immigrants from Mali around 1550, ie: more than a century after these buildings were constructed.

Partially excavated ruins of a 15th century building complex at Field A, Old Buipe, Ghana (photo by Denis Genequand, drawing Marion Berti)

ruins of a 15th century building complex at Field C, Old Buipe, Ghana (photo by Denis Genequand)

The Palaces of the Sudano-Sahelian style.

Documentary evidence indicates that several palaces were constructed by the rulers of Medieval Mali and Songhai in the sudano-sahelian architectural tradition, although archaeologists have yet to identify their location, save for a large banco structure at Niani (Mali) dated to the 14th century, that may have been an elite residence or a mosque.18

The rulers of Mali resided in a large, walled palace complex at the capital, described by Ibn Batutta in 1352, and the Askiyas of Songhai constructed their palaces in Gao as described by Leo Africanus in 1526. The 17th century Timbuktu chronicles also mention that the Sultan Kunburu, the ruler of Djenne in the 13th century (the medieval city near Jenne-Jeno), pulled down his old palace to build the large mosque of Djenne. He then constructed his new palace next to the mosque.19

The rulers of Mali and Songhay also had palaces in outlying towns like Diala, and Mansa constructed a palace in Timbuktu after his return from pilgrimage in 1324. Descriptions by Ibn Battuta and Leo Africanus indicate that these palaces were walled complexes, with large courtyards, audience chambers and multiple rooms, enough to house the royals, their attendants, palace guards, and many palace officials (secretaries, counsellors, captains, and stewards).20

Tomb and mosque of Askiya Muhammad of Songhai (r. 1493–1528), Gao, Mali, ca. 1920. ANOM.

Gao, Mali. ca. 1935, ANOM.

Similar, albeit smaller palaces from the later periods are better preserved much further south in northern Ghana, such as the Palace of the Wa-Na, which was built in the 19th century, following the distinctive architectural tradition that emerged in the region during the late middle ages, as seen in the elite houses of Buipe and the mosque of Larabanga.

A visitor to Wa in 1894 mentions that the “flat roofed buildings and date palms present it with an eastern appearance,” and another in 1895 notes the presence of the palace, described as a “rambling flat-roofed building.”21 The present structure is 'veritable labyrinth of courtyards' enclosed within white washed walls reinforced by thick buttresses with pinnacled tops and triangular perfolations.22

The palace of Wa in northern Ghana

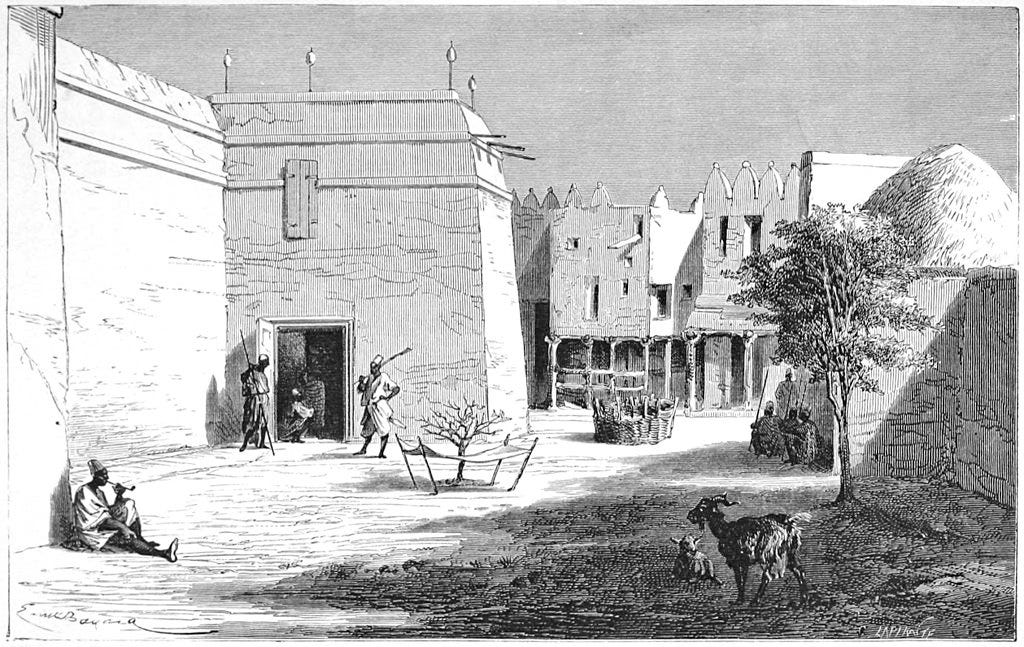

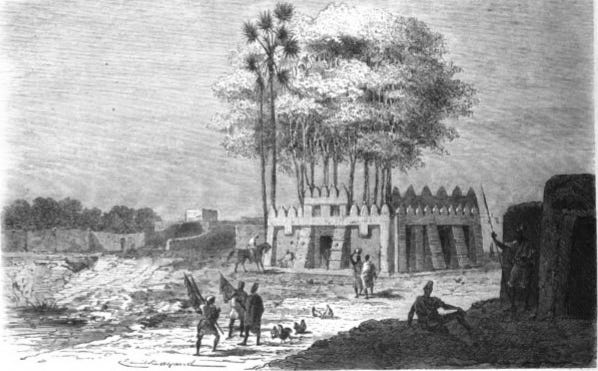

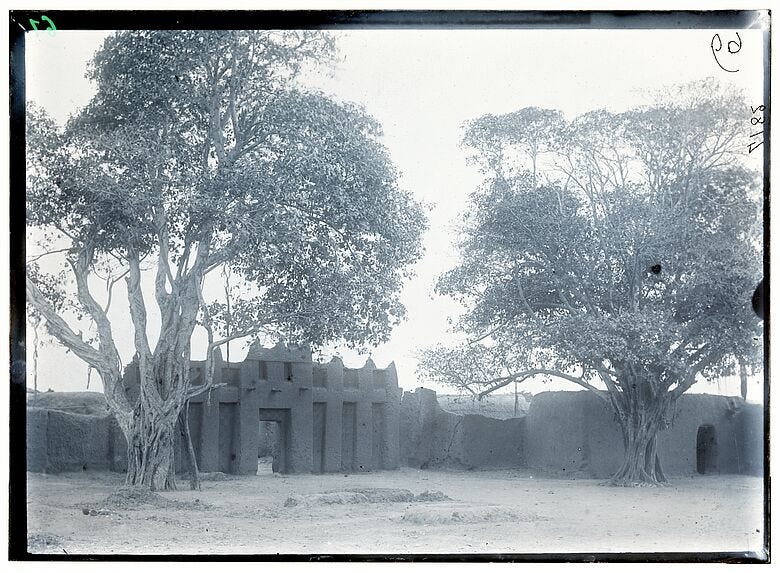

There are also multiple descriptions and images of the old palaces of Segou in Mali, which were constructed by the rulers of the Bambara empire and their sucessors —the rulers of the Tukulor empire.

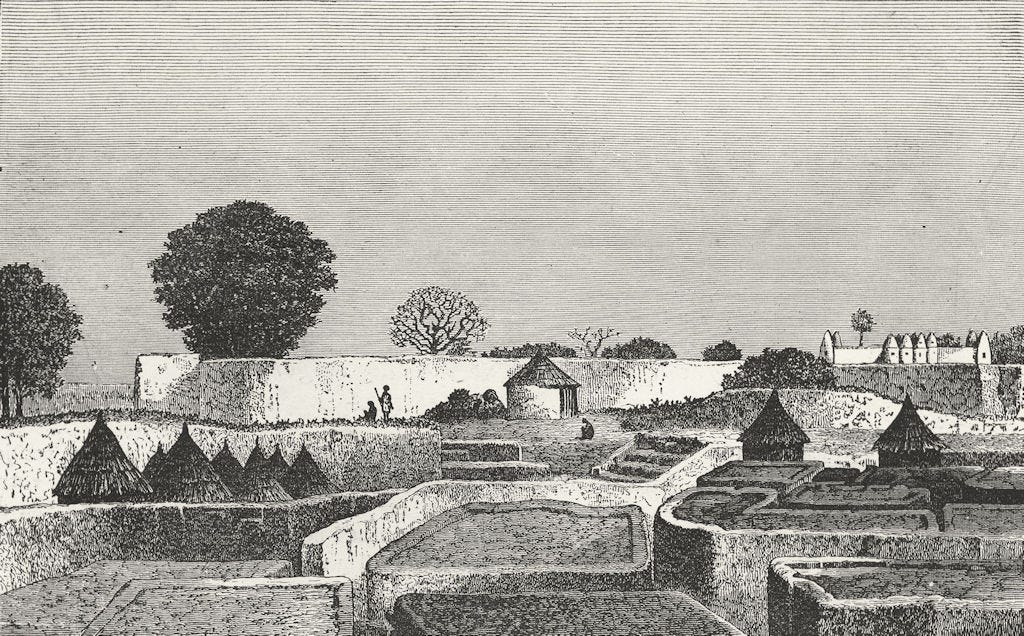

The account of Mungo Park, who visited the city around 1796 but wasn't allowed to meet the King, describes its general architecture as such: “Sego, the capital of Bambarra, consists of four distinct towns ; two on the northern bank of the Niger, called Sego Korro, and Sego Boo ; and two on the southern bank, called Sego Soo Korro, and Sego See Korro. They are all surrounded with high mud walls ; the houses are built of clay, of a square form, with flat roofs ; some of them have two stories, and many of them are white-washed. Besides these buildings, Moorish mosques are Seen in every quarter ; and the streets, though narrow, are broad enough for every useful purpose.”23

The account of the French traveler Eugene Mage, who visited Segou around 1866 when it was ruled by the Tukulor leader Ahmadou Tal, contains a description of his palace, which he described as an “ornate house” enclosed within “a real fortification six meters high, with towers at the corners and fronts in the middle, and in which two thousand defenders can be confined.” He also visited Ségou-Koro (old Ségou), and described “the remains of a highly ornamented earthen palace, the ruined facades of which are still standing, first strike the eye amidst the half-collapsed and deserted walls”.24

While these monuments didn’t survive long enough to be photographed, there are a number of images of the palace of Mademba Sèye, who was the fama (ruler) of Sansanding (in Mali) who took control of the town after the collapse of Ahmadou Tal’s empire to the French in 1890. The palace of Mademba, called the Diomfutu, was a fortified residence composed of a series of grand courtyards which are divided by numerous buildings, all of which were enclosed by walls that were decorated with pilasters, sculptures and ornaments. The whole measured 150 by 100 meters and its walls were five meters high. It was constructed around 1891 by local masons recruited by Mademba, who also rebuilt the walls of the town.25

The palace’s external appearence resembles the houses in the illustrations made by Eugene Mage, it also looks like the walled entrances to the compounds of elite houses in Nyamina and Segou, as well as the surviving buildings constructed by the Tukulor ruler Ahmadou (r. 1864-1893) at Segou such as the fortress and the ‘house of the sofas’, which were abandoned after the French invasion, and were photographed during the late 19th century.

entrance to Ahmadou’s Palace in Segou. ca. 1868, illustration by Eugene Mage.

House of the daughter of Mansong Diarra (ruler of the Bambara Empire 1795 to 1808) in Yamina, Mali. ca. 1868, Engraving by Eugene Mage.

The common house of the somonos of Ségou. ca. 1868, Engraving by Eugene Mage. the Somonos were part of the Bambara.

walled entrance to the palace of Mademba, Sansanding, Mali ca. 1900, BnF, Paris

House of the griot Soukoutou, in Ségou. ca. 1868, ilustration by M. Mage.

Photo of a house in Segou, ca. 1880-1889. Quai Branly. (this could be the same house with a slightly altered facade)

walled gate to a house in Nyamina, Mali. ca. 1880-1889, Quai branly

Segou, the house of the Sofas (warriors). ca. 1880-1889. Quai Branly

View of Ahmadou's Tata (fort) in Segou. ca. 1880-1889. Quai Branly. (this structure maybe the same as the one above)

View of Ségou, taken from a terrace. ca. 1868, illustration by M. Mage.

Segou was invaded by the French in April of 1890, who converted the former palace of Ahmadou into a colonial station/residence. The extent to which this later structure retained the architectural style of the old building is a subject of debate, because its colonial residents were involved in its reconstruction, unlike the other contemporaneous monuments (like the Djenne mosque and Aguibu's palace at Bandiagara) where local masons were in charge of the entire construction.26

French station at Segou, Mali. ca. 1880-1889. Quai Branly

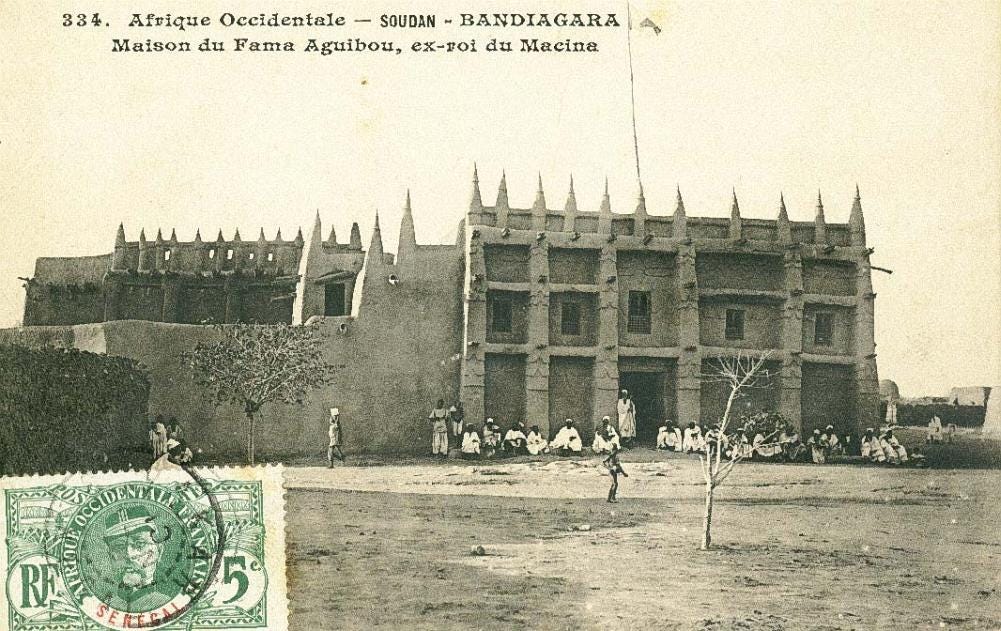

The palace at Bandiagara was constructed around 1893 by the ‘renowned masons from Djenne’ for the Tukulor ruler Agibou Tal according to a near-contemporary account by Henri Gaden. The three story structure, whose facade is topped by serrated pointed columns, was built in the traditional style, respecting local methods of construction.27 A slightly similar, but smaller palace was also constructed in the same region and appears in a few photographs from the early 20th century.

The Djenne masons are credited with the construction of a number of elite structures such as the palace of the Kélétigui Kourouma in Sikasso (Mali), while their southern counterparts, the Dyula, constructed several monuments in the region, especially at Bondoukou and Bouna (in Cote d‘ivoire), as well as the palace of the Senoufu King Gbon Coulibaly (1860-1963) at Korhogo during the early 20th century.28

Agibu’s palace at Bandiagara, Mali. image by Edmond Fortier, ca. 1906.

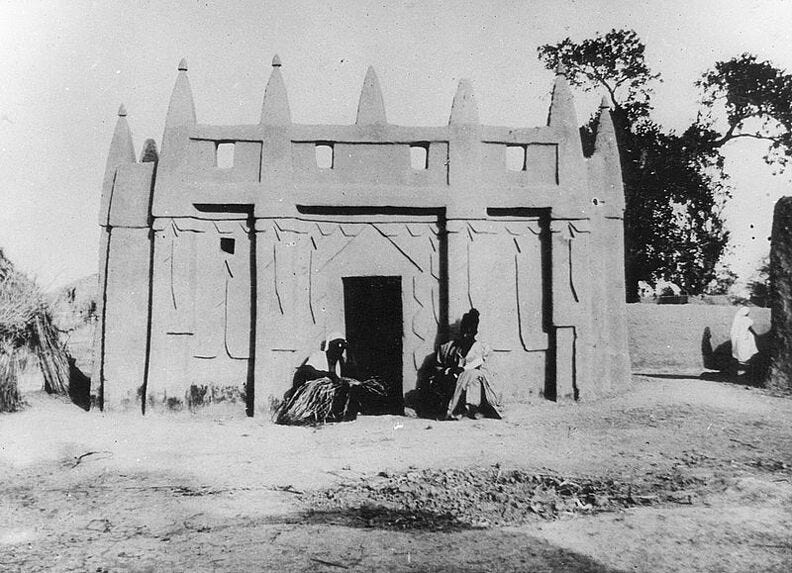

Chief’s house, Bandiagara, Mali. ca. 1911. Ethnological Museum of Berlin.

Palace of the Senufu king Gbon Coulibaly at Korhogo, Cote d‘ivoire, ca. 1926, Quai Branly. The roof of the palace had been destroyed by the time this photo was taken, Gbon told a later visitor in 1932 that the cause of this destruction was a storm.29

Some of the architects of the Sudano-Sahelian style

The specialist guild of masons of the medieval city of Djenne are renowned for constructing some of the most iconic palaces and mosques in the region. The mason guild was reportedly constituted during the heyday of imperial Mali and Songhai.

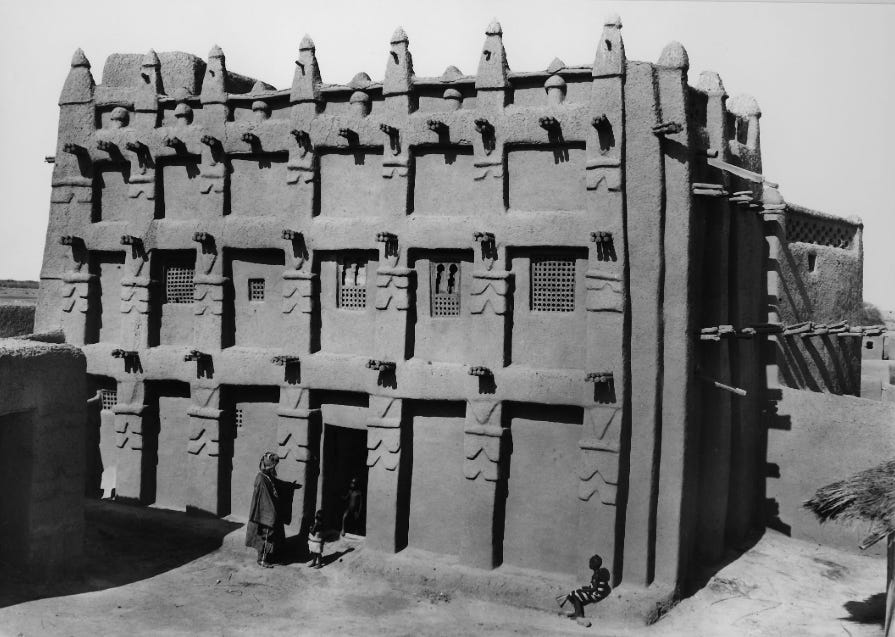

The 16th century Askiyas of Songhai employed 500 masons from Djenne at their provincial capital of Tendirma, the rulers of 19th century rulers of Segu and Massina employed masons from Djenne to construct their palaces and houses, long before they built the palace at Bandiagara and the iconic mosque of Djenne. The architectural style of Djenne city is characterized by tall, double or multi-story, terraced buildings, with massive pilasters flanking portals that rise vertically along the height of the façade.30

Their style of construction is best demonstrated at the Maiga House of Djenne, which was the residence of the chief of the songhay quarter, an office in the Massina empire that was held by Hasseye Amadou Maïga in the 19th century and would continue under his descendants during the tukolor empire.31 The large structure includes the typical features of Djenne architecture including thick buttresses (sarafa), conical pinnacles decorated with projecting beams (toron), and the so-called Façade Toucouleur (identified by its sheltered portal in contrast to the open portal of the more recent Façade Marocaine).32

the ‘Maiga House’ of Djenne.

An elite residence at Djenne with the Façade Toucouleur, ca. 1906. image by Edmond Fortier.

street scene showing terraced houses with the Façade Toucouleur, Djenne, Mali. ca. 1906, image by Edmond Fortier.

The Djenne masons are drawn from multiple groups in the city’s cosmopolitan population, that includes not just the Muslim population (Soninke, Songhay, Fulani) but also predominatly non-Muslim groups like the Bozo and Bambara. The architecture of the Bambara for example, also features buttresses and panel facades that are decorated with deep niches and low reliefs. The parapet of the flat roof is capped by pinnacles. In Bozo architecture, the ubiquitous saho were community houses for the youth, built with elements typical of the region's architecture including buttresses, pinnacles, corner pillars, portruding stakes (toron). All of these features can be seen at the Great Mosque of Djenne and other monuments.33

Types of Bambara houses, ca. 1892, illustration by Louis Binger.

decorated facade of a 'Saho' (youth house) ca. 1907-1908, Nohou, Mopti, Mali. Quai Branly

decorated facade of a 'Saho' (youth house) ca. 1907-1908, Diafarabé, Mopti, Mali. Quai Branly

Also related to these is the Dogon architecture of the Bandiagara region, which incorporates multiple regional styles, and also preserved some of the regions' oldest structures as mentioned above. Its distinctive façades are often composed of niches with checkerboard patterns, the walls buttressed by pilasters leading upto flat roofs surmounted by multiple rounded pinnacles.

The elder of an extended family lives in a large house (ginna) that is surrounded by the house of family members. The ginna is a two storied building with a façade showing rows of superimposed niches, while the ancestor altar (Wagem) is in a sheltered structure that leads onto the roof terrace surmounted by ritual bowls.34

House of the Hogon of Arou, Bandiagara, Mali.

Façade of different ginna houses in Sanga, Bandiagara, Mali.

Another important community associated with the a distinctive regional architectural style are the Dyula/Juula. These were a diasporic community of traders and scholars associated with the old cities of Djenne and Dia, who expanded southwards into the regions of Burkina Faso, northern Ghana and Cote D'ivoire in the 14th and 15th centuries.

The Juula are associated with the founding of the old towns of Begho, Bouna and Bondoukou during the late middle ages. Later waves of Juula migrants such as the Saganogo clan, are credited with the construction of the distinctive style of mosque architecture found throughout the region especially at Kong and Bouna, which also influenced later palace architecture as seen at the Palace of Wa mentioned above. Their ordinary houses consisted of rectangular flat-roofed houses organised around an open, internal courtyard.35

section of Bondoukou near one of samory’s residences, photo from the early 1900s

View of the Dyula town of Bondoukuo with one of its mosques.

Street scene in the Marabassou quarter of Kong, ca. 1892, ANOM.

The Mosque architecture

The Great Mosque of Djenne is easily the most recognisable architectural monument of the Sudano-Sahelian style.

The original mosque was a colonnaded structure constructed in the 13th century by sultan Konboro according to documentary accounts, and remained in use until the conquest of the city by the Massina empire in 1819 and 1821. The Massina founder Seku Ahmadu ordered its destruction because he considered its “excessive height” to be an example of the “blameworthy practices” of Djenne's scholary community mentioned in his polemical treatise Kitab al-Idtirar.36

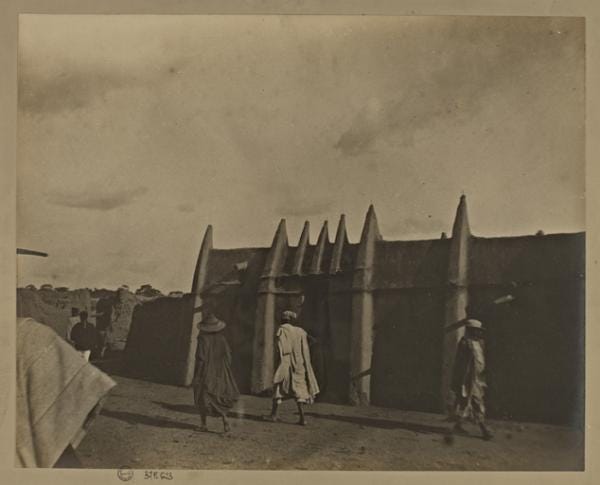

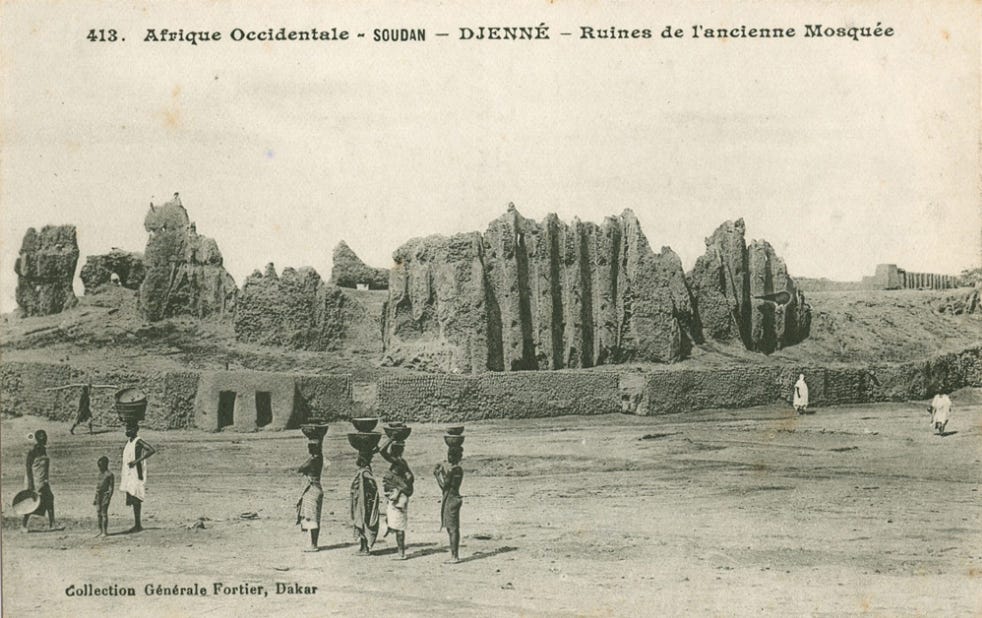

The Old mosque of Djenne, ca. 1895. image by A. Lainé, Quai Branly

By the time the French traveller Rene Caillie visited it in 1828, the mosque had spent more than a decade without being plastered and its mudbrick walls had been melted by the rain, leaving “a large structure” with “two massive towers.” Later photographs from the 1890s and 1900s showed that its walls had been eroded, but the outline of the original structure and parts of the colonnaded structure can still be seen. Another traveller, Felix Dubois, who visited Djenne in 1897, made a sketch of the mosque, consisting of a square enclosure punctuated by buttresses. In 1907, the Djenne masons guild, led by Ismaila Traoré, reconstructed the mosque in traditional style, with large buttresses (sarafa) and pinnacles that were typical of Djenne's elite houses of the 18th and 19th centuries.37

Ruins of the old Mosque of Djenne, ca. 1906, image by Edmond Fortier.

East elevation and floor plan of the Djenné Mosque by Pierre Maas and Geert Mommersteeg.

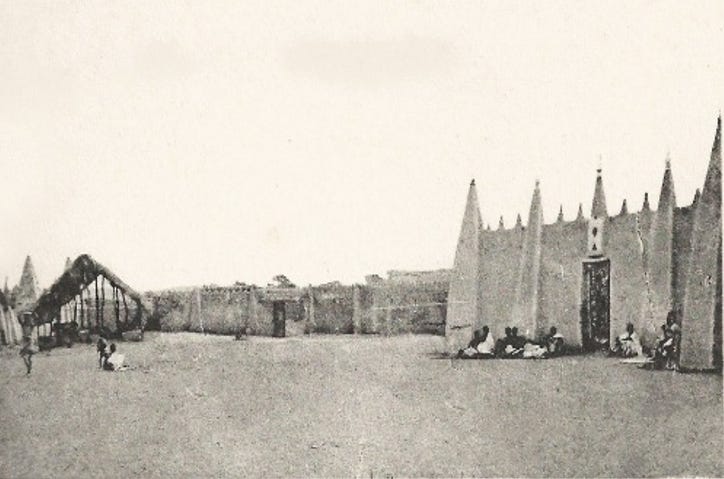

Related to these are two mosques in the Bandiagara region at Nando and Makou that are traditionally dated to the 14th century, and more recent mosques such as the one at kani kombole, which is dated to the late 19th and early 20th century.38 Similar, abeit low lying mosques from the 19th century are known from the cities and towns of Segou and Sansanding, that were built in the late 19th century. Their curtain walls are marked by buttressing, similar to the Djenne mosque but their mihrab tower is pyramidal in shape, similar to the Timbuktu mosques.39

The Dogon mosque of Nando, Mali.

The Dogon mosque of kani kombole, near Mopti, Mali.

Sansanding mosque, Mali, ca. 1907. Frobenius Institute

Mosque of Segou, Mali. ca. 1906. Edmond Fortier.

The second oldest extant mosque is the Jingereber mosque of Timbuktu which was built by Mansa Musa in 1325, a date that has recently been corroborated by radio-carbon dated material from the site. Archaeological excavations near the mosque and subsequent surveys of its architecture have shown that its building material and construction features were all characteristic ‘sudano-sahelian’ style of architecture of Djenne and other older sites, ruling out the purported influence of the Andalusian poet Abu Ishaq Es-Saheli.40

The original structure was later reconstructed in the 1560s during the Songhay period, extending to its current size of 70m by 40m, with a flat roof replacing the original vaulted roof. Two mudbrick mosques were added to the city in the first half of the 15th century; the Sankore mosque and the Sidi Yahya mosque, while the mosque next to Askiya's tomb at Gao was built in the 16th century.41

The Jingereber mosque of timbuktu, mosque plan by Bertrand Poissonnier.

The Sankore Mosque.

Sidi yahya mosque

Another iconic mosque built in the sudano-sahelian style is the great mosque of Agadez, which was originally constructed in the second half of the 15th century, and has gone through multiple reconstructions. The original mosque was built without its 28-meter tall minaret, which was only added ca 1515-1530, with additional reconstructions occurring in 1844 or 1847.42

Much further south, a number of old mosques were constructed in the 17th century at Larabanga (Ghana), in 1785 at Kong (Burkina Faso), in 1795 at Buna (Cote D'ivoire), in 1797 at Bondoukou (Cote D’Ivoire), in 1801 at Wa (Ghana) and in the late 19th century at Banda Nkwata (Ghana) and Bobo-Dioulasso (Burkina Faso).43

Friday Mosque of Kong, ca. 1920, Quai Branly.

Bobo Dioulasso’s Friday Mosque, ca. 1904, Quai Branly.

Most of these mosques share a number of common elements and architectural features identified with the 'Dyula' style of Sudano-Sahelian architecture such as façades that are structured by thick buttresses surmounted by pinnacles and linked together by horizontal wooden poles, a pillared prayer hall, a conical mihrab tower pierced by stakes and a roof terrace. The thick walls ensure the stability of the structure in the region's wetter climate, while the wooden poles serve as scaffolding and decoration. Larabanga mosque was built with cob (like other elite structures of Gonja's capital, Old Buipe) while the rest were built with clay and mud-brick.44

Larabanga mosque

Wa central mosque, early 20th century. image by I. Wilks.

Forts and city walls in the Sudano-Sahelian style.

The city walls and fortresses of the Sudano-Sahelian tradition are arguably the least studied of its monuments.

The oldest known city wall in the region was a 4m thick wall built around jenne-jeno during the 8th century, but this was likely constructed to hold back the floodwaters of the surrounding rivers. Similar enclosure walls surrounding the royal cities of Ghana and Mali are mentioned in accounts from the 11th and 13th centuries. The earliest defensive city wall was uncovered at the old city of Dia, where a crenellated wall built with mud-bricks was dated to the 14th century during the epoch of the Empire of Mali.45

(left) view of Dia-Shoma’s zigzag shaped city wall before excavation. (right) Shoma’s city wall after excavations, showing zigzag shaped wall with loaf-shaped mud bricks. images by N. Arazi.

Purely defensive fortifications proliferated across the region during the 18th and 19th centuries and are mentioned in multiple contemporary accounts. These fortifications commonly known as 'Tata', were not built with mudbrick like at Dia, but were instead mostly made of rammed earth (sana) that was piled into courses and tempered with lateritic gravel stones. Larger towns such as Ton Masala were enclosed by three concentric crenellated walls upto 4m thick and 5m tall, mostly for ideological reasons, while smaller towns and even villages were surrounded by walls over 2m tall, mostly for defense.46

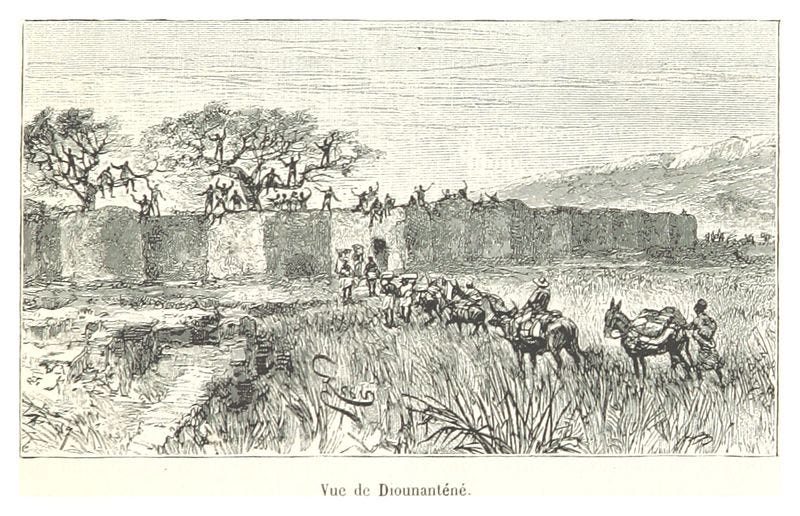

Illustrations of these are contained in the travel accounts of several explorers, notably Louis Gustave Binger, who travelled from Senegal, to southern Mali and northern Ivory coast, and noted the presence of multiple walled settlements such as at Tiongui, Dioumaténé and Sikasso in Mali.

Tata of Tiong-i, Mali. ca. 1892. illustration by L. Binger. “Tiong or Tiong-i has the appearance of a city: its large clay walls of ash gray clay with coarse flanking towers spaced 25 to 30 meters apart”

The Tata of Sikasso, Mali. ca. 1892, illustration by Louis-Gustave Binger. The walls of sikasso enclosed the entire town, with a diameter of 9km, width of 6 m at the base, and a height of over 6 meters.

View of Diounanténé, ca. 1892, Mali. illustration by L. Binger.

The walled town of Douabougou, Mali. ca. 1885, Mali. NYPL.

Much larger fortresses of stone and rammed earth, were built under the Tukulor ruler Umar Tal by his famed architect, Samba N’Diaye at Segu, Bakel, Nioro, and Koundian, etc. Eugune Mage's account from 1866, describes the fort at Nioro as a “vast square, measuring 250 feet each side built regularly in stones daced with earth... The walls are about 2.5m thick, on the four corners there are round towers and the whole is between 10 and 12 meters high... It is absolutely impenetrable without artillery.” 47

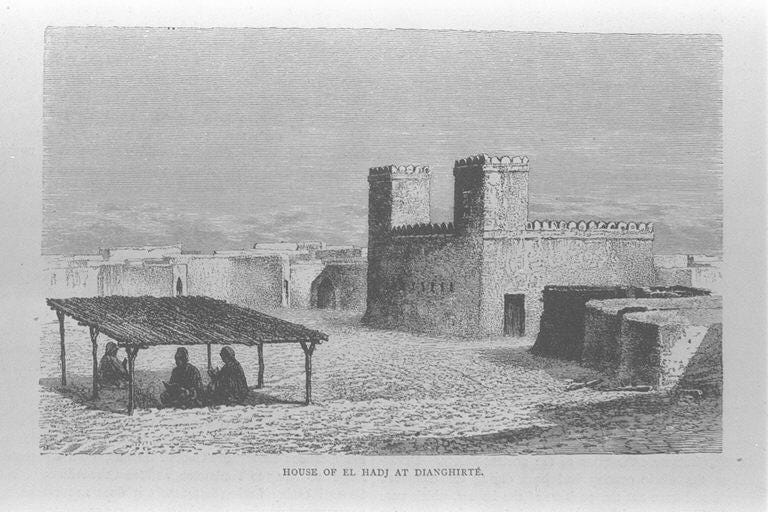

House of El Hadj, in Dianghirté. ca. 1868, Illustration by Eugène Mage. the latter described it as a “tata or palace of El Hadj. built with rammed earth like the other buildings in the village, and decorated with two square towers in good condition, and crowned like other parts, with a serrated or festooned ornament in the Moorish style.”

Umar Tal’s Stone fortress of Koniakari shortly after it was breached. ca 1890, Quai Branly.

Tata of Umar Tal between Nioro and Segou, Mali. ca. 1898, ANOM.

Similar monumental walls surrounded the Massina capital Hamdallaye during the mid 19th century, and the Senufo city of Sikasso in the late 19th century. The Sikasso walls enclose the 90 ha capital entirely, they were crenellated in form and measured 6 m in height with a thickness of between 1.5 and 2 m at its base. Other walled towns can be found across southern Burkina Faso near Kong and Say.48

the tata (fortification) of Sikasso after the two-week French artillery barrage breached it. ca. 1898, ANOM.

There are also multiple descriptions of walled towns and fortifications in the senegambia region during the 18th and 19th centuries, which were also built with rammed earth.

A description of Bulebane, the capital of Bundu (Senegal) by British traveler, William Gray in 1825, mentions that: “The town is surrounded by a strong clay wall, ten feet high and eighteen inches thick; this is pierced with loopholes, and is so constructed that, at short intervals, projecting angles are thrown out, which enable the besieged to defend the front of the wall by a flanking fire.” a later description of the same town in 1846 notes that its walls were “interrupted quite frequently by square or round towers and bastions and it is closed by several solid doors.”49

Mosque and Fortress at Podor, Senegal. ca. 1917. images reproduced by Cleo Cantone.

Studies of the region’s architectural history reveal that these fortifications influenced the palace and mosque architecture of the Senegambia. The 19th century descriptions of the town of Guede for example, mention the presence of; a tall bastioned enclosure whose interior is divided into compartments by different walls; the king's audience hall which was a square building of 10 meters that was about 7meters tall; as well as a mosque and ordinary homes.50

Mosque of guede in Senegal. images by Cleo Cantone. First constructed in the late 17th century, it was renovated in the 18th and 19th centuries in the sudano-sahelian style with tapering pillars.51

Sudano-Sahelian architecture during the colonial and post-independence period.

As mentioned above, the construction of monuments in the Sudano-Sahelian style continued during the colonial period, some of which retained their older aesthetics while some evolved in the new social and cultural milieu.

Throughout the early 20th century, a series of public buildings were constructed which combined Sudano-Sahelian, Hausa and colonial architecture. This neo-Sudanese style is described by one ethnographer as a “monumental style [that] has even been adopted with gratitude by the French entrepreneurs in the French Sudan and employed with certain alterations on public buildings, under the name neo-Sudanese Style.” It was especially common in market buildings and a few colonial residences.52

Market in Bamako, Mali. early 20th century.

Numerous mosques and palaces were also constructed across west Africa, often by wealthy Africans, such as the mosque at San and Mopti.

The Sudano-Sahelian architectural style continued during the post-colonial period, as seen at the Bani mosques of Burkina Faso (built in 1978), and the iconic BCEAO Tower in Mali, (built in 1985). This style of construction is today considered one of Africa’s Indigenous Architectural styles, and has spread beyond its heartland to other parts of the continent and the world.

Mosque in Bani, Burkina Faso, the biggest of the seven mosques that were built by Mohamed el Hajj. interestingly, none are directed toward mecca, they instead face the largest mosque at the center.

The BCEAO Tower, Bamako, Mali.

African Museum in Jeju Island, South Korea

West Africa’s architectural tradition predates the arrival of Islam, as i have shown in the above essay. My latest Patreon Article explores the three pre-Islamic sites of Loropeni, Oursi, and Kissi in greater detail. These large nucleated settlements featured massive stone walls enclosing elite houses, a double-storey building complex, and an elite cemetery with grave goods imported from the Roman provinces of North Africa and Spain.

please subscribe to read about them here

Spatial Organization and Socio-Economic Differentiation at the Dhar Tichitt Center of Dakhlet el Atrouss I (Southeastern Mauritania) by Gonzalo J. Linares-Matás, The Tichitt Culture and the Malian Lakes Region by Robert Vernet et al.

The Tichitt tradition in the West African Sahel by K.C. MacDonald, late neolithic cultural landscape, Late Neolithic Cultural landscape in southeastern Mauritania: An Essay in spatiometry by Augustin Ferdinand Charles Holl, Tichitt-Walata and the Middle Niger: Evidence for Cultural Contact in the Second Millennium BC by K.C. MacDonald

Betwixt Tichitt and the IND: the pottery of the Faïta Facies, Tichitt Tradition by K.C. MacDonald pg 58-67

On the Margins of Ghana and Kawkaw: Four Seasons of Excavation at Tongo Maaré Diabal (AD 500-1150), Mali by Nikolas Gestrich, Kevin C. MacDonald pg 7-8.

Excavations at Jenné-Jeno, Hambarketolo, and Kaniana, edited by Susan Keech McIntosh, pg 64-65, 215-216, Tracing history in Dia, in the Inland Niger Delta of Mali : archaeology, oral traditions and written sources by N. Arazi, pg 125-126

Excavations at Jenné-Jeno, Hambarketolo, and Kaniana, edited by Susan Keech McIntosh, pg 44-45, 48, 51-53, 433-447, 367-369, Tracing history in Dia, in the Inland Niger Delta of Mali : archaeology, oral traditions and written sources by N. Arazi pg 135-146

Une chronologie pour le peuplement et le climat du pays dogon by Sylvain Ozainne et al. pg 42)

The Archaeology of Africa: Food, Metals and Towns edited by Bassey Andah, Alex Okpoko, Thurstan Shaw, Paul Sinclair pg 256-257, The Kintampo Complex: The Late Holocene on the Gambaga Escarpment, Northern Ghana by Joanna Casey pg 119-121.

Agricultural diversification in West Africa by Louis Champion et al pg 15-16, Early social complexity in the Dogon Country by Anne Mayor, Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara by Alisa LaGamma pg 162)

Excavations at Gao Saney: New Evidence for Settlement Growth, Trade, and Interaction on the Niger Bend in the First Millennium CE by M Cissé pg 25, 30)

Archaeological Investigations of Early Trade and Urbanism at Gao Saney by M. Cisse 123, 133, 256-268.

Archaeological Investigations of Early Trade and Urbanism at Gao Saney by M. Cisse pg 269-270, Discovery of the earliest royal palace in Gao and its implications for the history of West Africa by Shoichiro Takezawa pg 10-11, 15-16.

Excavations at Gao Saney: New Evidence for Settlement Growth, Trade, and Interaction on the Niger Bend in the First Millennium CE by M Cissé pg 30-31)

Oursi Hu-beero: A Medieval House Complex in Burkina Faso, West Africa edited by Lucas Pieter Petit, Maya von Czerniewicz, Christoph Pelzer pg 39-41

Oursi Hu-beero: A Medieval House Complex in Burkina Faso, West Africa edited by Lucas Pieter Petit, Maya von Czerniewicz, Christoph Pelzer pg 43-76.

Les Ruines de Loropéni au Burkina Faso by Lassina Simporé pg 260, Fouilles archéologiques dans le compartiment by Lassina Kote pg 97-98, 102-103, 109

Preliminary Report on the 2019 Season of the Gonja Project, Ghana by Denis Genequand et al. pg 287, Excavations in Old Buipe and Study of the Mosque of Bole (Ghana, Northern Region) by Denis Genequand et al. pg 26

Landscapes, Sources and Intellectual Projects of the West African Past ... Pg 53-56, Le complexe du palais royal du Mali by W. Filipowiak

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Saʿdi's Taʾrīkh Al-Sūdān Down to 1613, and Other Contemporary Documents by John Hunwick pg 10, 19.

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Saʿdi's Taʾrīkh Al-Sūdān Down to 1613, and Other Contemporary Documents by John Hunwick pg 109, 283)

Wa and the Wala: Islam and Polity in Northwestern Ghana By Ivor Wilks pg 6-7

The Conservation of Smaller Historic Towns in Africa South of the Sahara. With Case Studies of Two Ghanaian Examples, Elmina and Wa",by M. A.D.C. Hyland.

Travels in the interior districts of Africa by Mungo Park

Le tour du monde: nouveau journal des voyages, Volumes 17-18 edited by Edouard Charton, pg 71-73

Conflicts of Colonialism: The Rule of Law, French Soudan, and Faama Mademba Sèye By Richard L. Roberts 89, 97, 99, 103, 130-131

Double Impact: France and Africa in the Age of Imperialism by G. Wesley Johnson pg 226)

Nearly Native, Barely Civilized: Henri Gaden’s Journey through Colonial French West Africa (1894-1939) By Roy Dilley pg 50-51,

Gbon was his Dyula name, his senufu name was Peleforo Soro, although the influence of the Dyula was such that he was mostly known for his Dyula name. see: State Formation and Political Legitimacy edited by Ronald Cohen, Judith D. Toland pg 46-47.Political Topographies of the African State By Catherine Boone pg 247-261

L'Enfer des noirs. Cannibalisme et fétichisme dans la brousse ; Author, Jean Perrigault pg 122

Historic mosques in Sub saharan by Stéphane Pradines pg 101, Butabu: Adobe Architecture of West Africa By James Morris, Suzanne Preston Blier pg 194-196, Making and Remaking Mosques in Senegal By Cleo Cantonepg 68

African Arts, Volume 30, University of California, pg 93

Historic mosques in Sub saharan by Stéphane Pradines pg 101, The Masons of Djenné by Trevor Hugh James Marchand pg 88

Historic Mosques in Sub-Saharan Africa: From Timbuktu to Zanzibar By Stéphane Pradines pg 104.

L'architecture dogon: Constructions enterre au Mali, edited by Wolfgang Lauber, Dogon: Images & Traditions by Huib Blom pg 228-238

The History of Islam in Africa by Nehemia Levtzion pg 101, Making and Remaking pg 41-45, 47

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 137-141

The History of the Great Mosques of Djenné by Jean-Louis Bourgeois, Making and remaking msoques pg 184

Dogon: Images & Traditions by Huib Blom pg 282, 286, 291, Historic Mosques in Sub-Saharan Africa: From Timbuktu to Zanzibar by Stéphane Pradines pg 102-103

Making and Remaking Mosques in Senegal By Cleo Cantone pg 40)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire edited by John O. Hunwick pg 30 n.8, The great mosque of timbuktu by Bertrand Poissonnier pg 26-34, 69)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire edited by John O. Hunwick pg 30 n.8, The great mosque of timbuktu by Bertrand Poissonnier pg 81-82,

La grande mosquée d'Agadez : Architecture et histoire by Patrice Cressier & Suzanne Bernus.

The History of Islam in Africa edited by Nehemia Levtzion, Randall L. Pouwels pg 101)

Making and remaking pg 40-41, Preliminary Report on the 2016 Season of the Gonja Project by Denis Genequand pg 96-108

The least of their inhabited villages are fortified”: the walled settlements of Segou by Kevin C. MacDonald pg 365-366)

The least of their inhabited villages are fortified”: the walled settlements of Segou by Kevin C. MacDonald pg 347-348, 356-360)

Making and Remaking Mosques in Senegal By Cleo Cantone pg 65-67

The least of their inhabited villages are fortified”: the walled settlements of Segou by Kevin C. MacDonald pg 345

Making and Remaking Mosques in Senegal By Cleo Cantone pg 55-57)

Making and Remaking Mosques in Senegal By Cleo Cantone pg 59-62, Voyage à Ségou, 1878-1879 by Paul Soleillet pg 38.

The Rural Mosques of Futa Toro by Jean-Paul Bourdier

Making and Remaking Mosques in Senegal By Cleo Cantone pg 186-187)

Still making my way through this but, amazing work so far! Thanks for capturing such important and fascinating roots of our ancestry.

When I opened my mail and saw the title, I just knew this was gonna be a banger and I was not disappointed.. Thanks .