The Intellectual Foundations of African Proto-Nationalism and the “invention” of Nations in the 19th Century

“What led to this production was not a burning desire of the author to appear in print, but a purely patriotic motive, that the history of our fatherland might not be lost in oblivion.”1

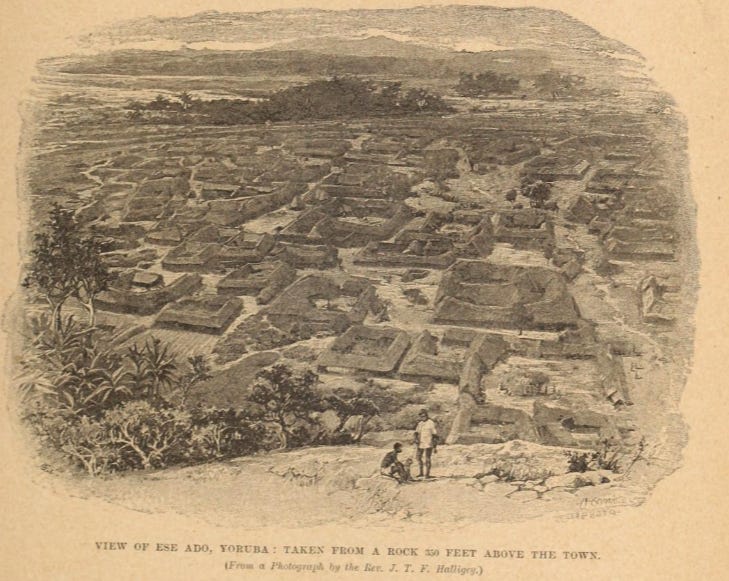

Samuel Johnson’s ‘History of the Yorubas’ (1899) is a seminal work in modern African historiography. It chronicles the social and political transformations of 19th-century Yorubaland (S.W. Nigeria), a period marked by the emergence of multiple city-states as well as the simultaneous spread of Islam, Christianity, and colonialism.

Johnson is often regarded as part of the first generation of African nationalists, “who were able to work within the paradigms of the precolonial nations while also imagining an African modernity.”

These were the first African intellectuals whose experiences in the Atlantic world induced them to develop a national consciousness and to cultivate new and larger social identities/ethnicities, such as the ‘Yoruba,’ whose shared history, language, and culture became ‘ethnographic units’ of study by later academic historians.2

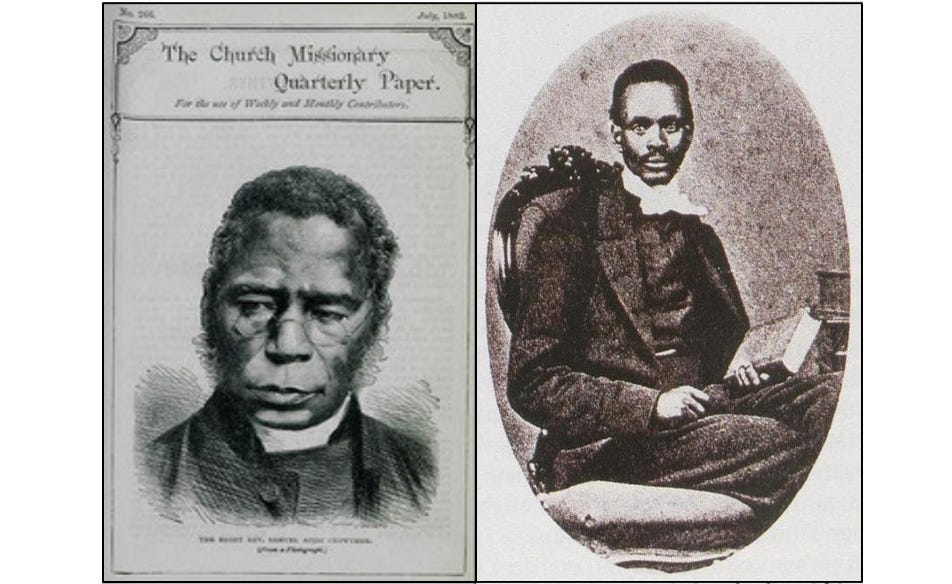

The historian Samuel Johnson, along with the famous Bishop and linguist Ajayi Crowther, are at times considered the first ‘proto-Yoruba’; in the sense of being among the earliest to identify collectively as Yoruba and, through their writings, to consolidate the diverse sub-groups that had previously constituted this heterogeneous social group, such as the Oyo, Ijesha, Egba, Ijebu, Ekiti, and Ondo.3

The Yoruba town of Ese Ado, Nigeria, ca. 1892

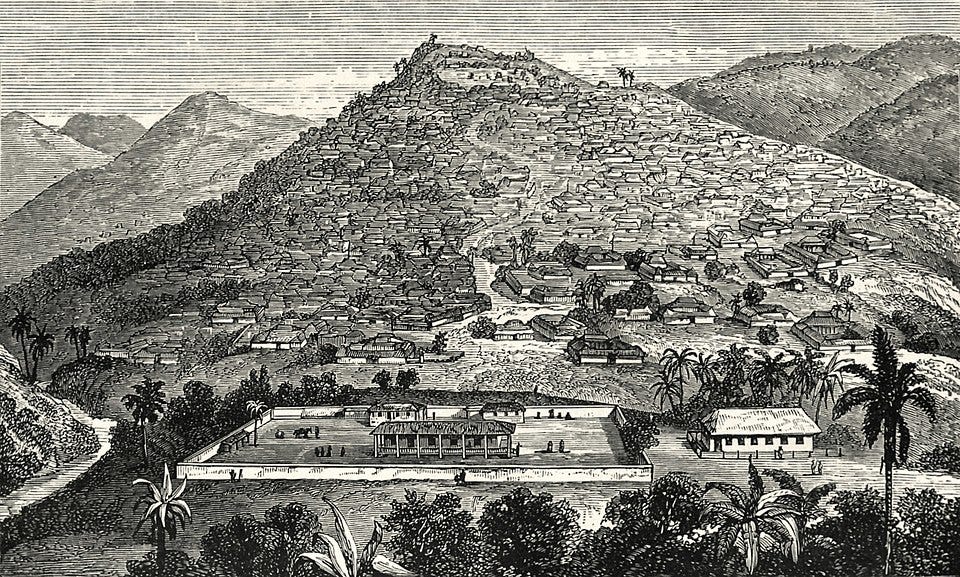

Engraving depicting Ibadan in 1854. Samuel Johnson spent most of his career in Ibadan

Oyo and its neighbours in the late 19th century. Map by P. Lovejoy.

Johnson did not “invent” the term Yoruba, which first appears in the 17th-century writings of the Timbuktu scholar Ahmad Baba as an exonym associated with the kingdom of Oyo. The term was then transmitted to the Fodiyawa scholars of Hausaland in the 19th century, whose writings provide some of the sources cited in Johnson’s account.4

Despite his Christian background, in which mission education often discouraged engagement with African cultural history, Johnson called for its preservation.

He used traditional accounts to reconstruct the more recent history of the Yoruba, which forms the bulk of his book, and Muslim accounts for its ancient history, including the story of the dispersion of Noah’s descendants and Nimrod, the grandson of Ham. He also posits an ancient connection with the Coptic Church, in part to situate his own Christian identity within the broader trajectory of Yoruba history.5

Johnson was among the transitional figures in African history who stood at the confluence or collision point of two worlds, one African and the other Western. While these figures engaged with foreign ideas and technologies, they did not do so uncritically, but used them to assert their African identity.

They were cultural translators and ‘modernizers’ who bridged the two worlds, but seemingly belonged to neither. Some, like Johnson, whose career was shaped by the internecine wars of late 19th-century Yorubaland, sought to negotiate their relationship with the colonial power, while others openly opposed imperial expansion.

It is this distinct historical context alone that differentiates the writings of the proto-nationalists of the late 19th century from those of later African nationalists such as Kwame Nkrumah and Julius Nyerere, whose political thought was forged under colonial domination and informed by active anti-colonial struggle.

In a previous essay on Early industrialization and modernization in 19th-century Africa, I examined the role of modernizers such as the Ansa family of Asante (Ghana) who sought to develop their kingdom while maintaining local sovereignty. They drafted plans for railroads, reformed the civil service, and procured modern rifles for the army.

While the Ansas were integrated into the administrative apparatus of the Asante kingdom and could utilize state resources to achieve their objectives, figures like Samuel Johnson remained in the intermediary zone between the pre-colonial and colonial societies. For such individuals, the pen became a crucial instrument for contesting hegemonic narratives that marginalised African history.

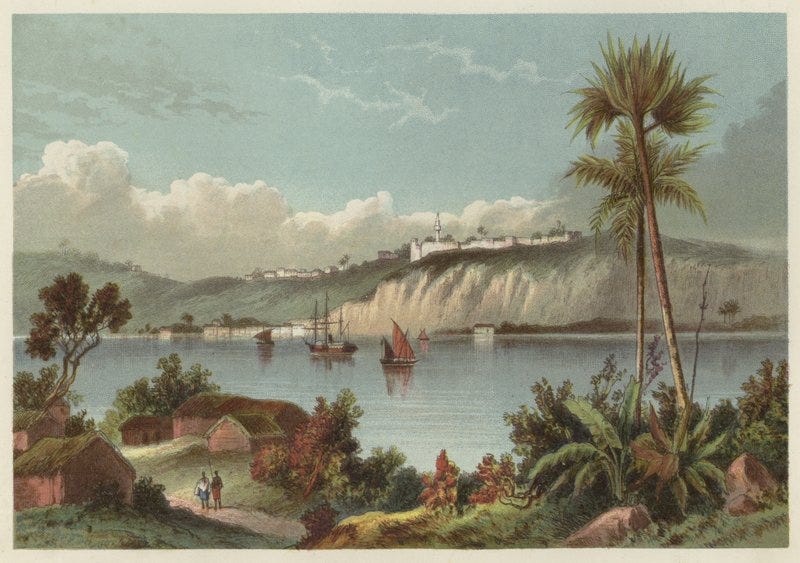

In Angola, the writings of the mestiço journalist José de Fontes Pereira exemplified a more radical strain of African proto-nationalism. In a now-famous 1882 article, he sharply criticized the Portuguese authorities for excluding qualified Africans from participation in local administration:

“How has Angola benefited under Portuguese rule? The darkest slavery, scorn and the most complete ignorance! And even the Government [in Luanda] has done its utmost to the extent of humiliating and vilifying the sons of this land who do possess the necessary qualifications for advancement.

. . . What a civilizer, and how Portuguese!”6

St. Paul de Loanda, ca. 1854. Illustration by David Livingstone.

In South Africa, during the 1880s, the Xhosa poet Isaac Citashe represented the more moderate brand of African proto-nationalism. Writing after the century-long colonial wars had devastated Xhosaland from 1779-1879 and further entrenched racially discriminatory laws, Citashe urged for the continuation of the struggle for African rights, not with weapons of war but with pen and ink:

“Your rights are plundered!

Grab a pen,

Load it with ink;

Fire with your pen.”7

Through their writings, these early nationalists placed African consciousness and identity within a larger framework of modern history, while affirming the value of their particular nationalities.

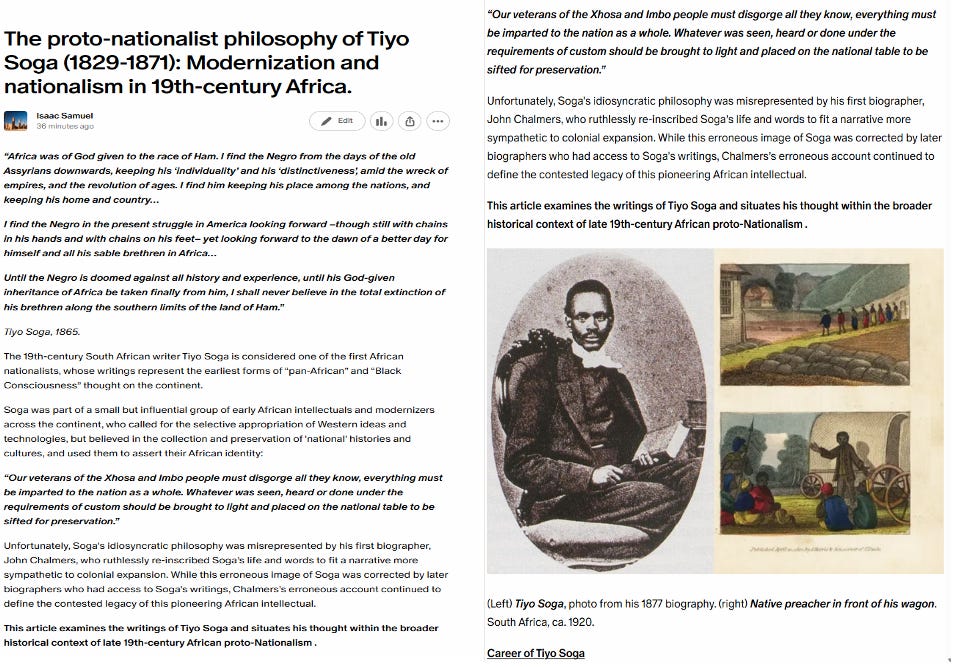

This form of proto-Nationalism is best exemplified by the Xhosa writer Tiyo Soga (1829-1871), a towering figure in the history of southern Africa who was one of the most prolific African intellectuals of the 19th century.

Soga advocated for cultural adaptation to modernization, but was the first to identify himself and the multiple African polities of the Eastern Cape as a part of a distinct ‘Xhosa’ nation, with a shared history and culture:

“Our veterans of the Xhosa and Imbo people must disgorge all they know, everything must be imparted to the nation as a whole. Fables must be retold; what was history or legend must be recounted.

Whatever was seen, heard or done under the requirements of custom should be brought to light and placed on the national table to be sifted for preservation. Let us resurrect our ancestral fore-bears who bequeathed to us a rich heritage.”

He called for the selective appropriation of modern ideas and technologies, but opposed the more unsavory vices of capitalism, whose “laws are as unchangeable as those of the Medes and Persians”. He condemned racial discrimination and advocated for the respect of African rulers whose authority was undermined by encroaching settlers, whom he referred to as “the outlaws and refuse” of the mother country.

He repeatedly challenged his colleagues (who had dismissed the Xhosa as destined for extinction under colonial expansion) by placing Xhosaland in the universal history of Africa and the African diaspora:

“Africa was of God given to the race of Ham. I find the Negro from the days of the old Assyrians downwards, keeping his ‘individuality’ and his ‘distinctiveness’, amid the wreck of empires, and the revolution of ages. I find him keeping his place among the nations, and keeping his home and country…

I find the Negro in the present struggle in America looking forward – though still with chains in his hands and with chains on his feet – yet looking forward to the dawn of a better day for himself and all his sable brethren in Africa…

Until the Negro is doomed against all history and experience until his God-given inheritance of Africa be taken finally from him, I shall never believe in the total extinction of his brethren along the southern limits of the land of Ham.”

The proto-Nationalist philosophy of Tiyo Soga is the subject of my latest Patreon article. Please subscribe to read more about it here, and support this newsletter:

(left) Portrait of Samuel Ajayi Crowther. The Church Missionary Quarterly Paper, July 1882. (right) Tiyo Soga, photo from his 1877 biography.

The History of the Yorubas From the Earliest Times to the Beginning of the British Protectorate By Samuel Johnson, pg vii.

Nigeria, Nationalism, and Writing History By Toyin Falola, Saheed Aderinto, pg 16-20

Religious Encounter and the Making of the Yoruba By John David Yeadon Peel, J. D. Y. Peel, pg 278-281, The Cultural Work of Yoruba Ethnogenesis by J. D. Y. Peel, pg 201-206, in History and Ethnicity edited by E. Tonkin, M. O. McDonald, and M. Chapman

Slaves and Slavery in Africa: Volume One: Islam and the Ideology of Enslavement by John Ralph Willis, pg 137, Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Sa’di’s Ta’rikh al-Sudan down to 1613, and other contemporary documents / [translated and edited] by John O. Hunwick pg xxvii, Lii, n. 104

The Cultural Work of Yoruba Ethnogenesis by J. D. Y. Peel, pg 206-9, History of the Yorubas, by Samuel Johnson, CMS, Lagos, Nigeria, pg 7

”Angola Is Whose House?” Early Stirrings of Angolan Nationalism and Protest, 1822-1910 by Douglas L. Wheeler, pg 1

Africans and Britons in the Age of Empires, 1660-1980. By Myles Osborne, Susan Kingsley Kent, pg 55

Agreed. Becoming acquainted with the author Isaac Samuel's work, writings have restored my hope that an equitable sharing of our (Negro) historical life, times and role in civilization is possible, and advancing.

African nationalism was not to any significant level behind that of the Eurasian world. Not saying the article says this, saying this because alot of people like to make this argument.

Many scholar dispute the very idea of old national and at times, even ethnic identities anywhere in the world and up to the last of the balkan wars, people's ethnic identities in the Balkans shifted with which nationalist state controlled them.