Early industrialization and modernization in 19th century Africa

During their first encounter at the end of the Middle Ages, the political and social structures of European and African kingdoms were broadly similar, and as I explored in this critique of Acemoglu in Kongo, African economies could not be significantly influenced by the actions of European merchants.1

Militarily, the Portuguese empire, which suffered stunning defeats along the western coast of the Mali empire and in South Africa against the Khoi-San, briefly managed to carve out a large colonial empire over parts of Angola, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and the East African coast during the early 1600s, before losing most of it to resurgent African rulers like King Changamire and Queen Njinga.

But by the 19th century, the industrial and political revolutions conferred significant advantages to a handful of states in western Europe that would become more evident as the century wore on, even though powerful African kingdoms like Asante could maintain their military advantage over invading European armies.

Throughout the 19th century, African envoys and travelers, who had been visiting Western Europe since the 1600s, began sending back reports on these rapid changes and recognized the need to modernize quickly if they were to retain their autonomy.

In the kingdom of Imerina (Madagascar), for example, King Radma I (r. 1810-1828) undertook an ambitious program of modernisation. Schools in the capital adopted a British and French-style syllabus, with some students being sent abroad for instruction in engineering, military training, and factory textile production. Foreign industrialists set up factories that were jointly owned by the state, which specialised in the production of textiles, refined sugar, military equipment and ammunition, glassware, and construction material.

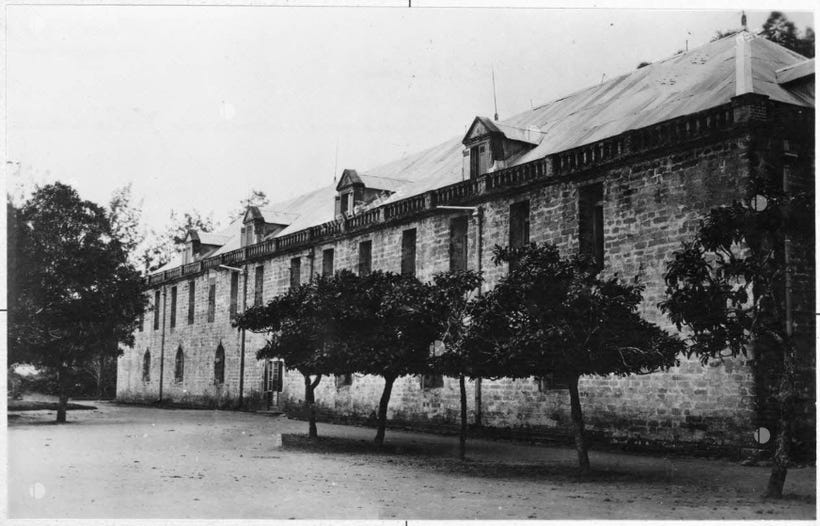

19th century Factory building Mantasoa, Madagascar, ca. 1900, imagesdefense.

Mantasoa glass oven, ca. 1914, imagesdefense. Both structures were part of the industrial complex at Mantasoa, comprising five factories, which were jointly owned by the Merina state and the entrepreneur Jean Laborde.

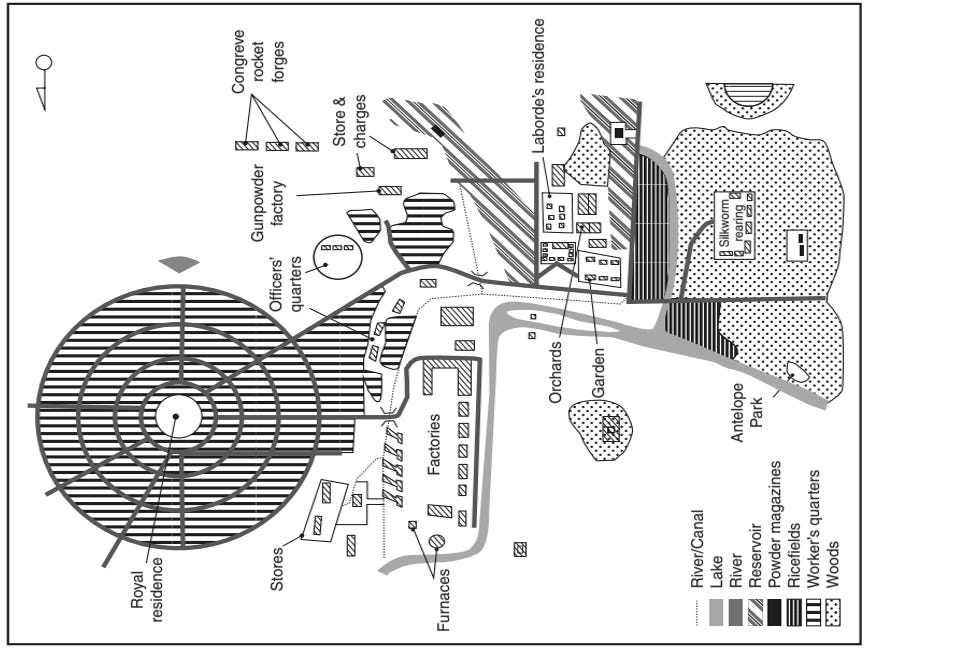

Mantasoa industrial complex in the early 19th century. Illustration by G. Campbell

Similar programmes of modernisation were undertaken to a greater extent by the Pashas of Egypt, especially Muhammad Ali (r. 1805-48), and to a lesser extent in Ethiopia during the reign of Tewodros II (r. 1855-68) and in the Zanzibar sultanate during the reign of Barghash (r. 1870-88).

In these societies, the transfer of modern technology was attempted through the direct recruitment of foreign personnel (Tewodros went as far as to forcefully detain them), and supplemented by sending students abroad to quickly replace foreign with indigenous expertise.2

Zanzibar seafront, ca. 1890, showing the clock tower, the Sultan’s palace (center), a public water cistern in the shape of a ship’s hull, streetlights, and old cannons.

In kingdoms like Asante, where contacts with the industrialized West were relatively less direct, the modernization process was undertaken by envoys and students who were educated in the West and later appointed to local administration. The most notable of these were Owusu Ansa and his son John Ansa.

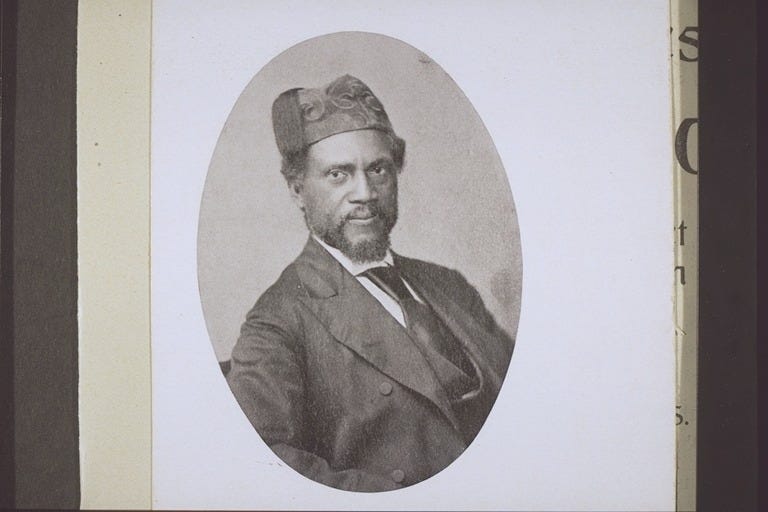

Owusu Ansa, who was born in Asante’s capital, Kumasi, in 1823, was educated in England from 1836-1841, and served a succession of Asante kings. He later became a senior advisor to King Mensa Bonsu (r. 1874-83), whom he influenced to reform the kingdom’s civil service, modernise its military, and recruit European entrepreneurs with the intention of constructing factories in Asante. However, their ambitious plans were cut short by Mensa Bonsu's overthrow in 1883 and Owusu’s death in 1884.3

His son, John Ansa, was born in Kumasi in 1851 and educated in the British Cape Coast Castle before later becoming an advisor to King Agyeman Prempeh (r. 1888-96) as an official envoy to the British colony of the Gold Coast.

Continuing his father's plan to develop Asante's economy through the participation of European capital, he influenced Prempeh’s decision to set up a company with Dr. J. W. Herivel in 1892, which would finance and manage the construction of railroads and the development of industry in Asante.

However, Dr. Herivel’s plans to apply for a charter in London were blocked by the colonial authorities of the Gold Coast in 1893, who “viewed the project with considerable alarm, and deemed it expedient to deter Herivel from pressing forward with a scheme which might greatly have strengthened the Asante economy.”4

Not to be outdone by the increasingly hostile Gold Coast governor, John Ansa travelled to London in late 1895, and begun the process of forming a chartered company with an even broader range of responsibilities than Herivel’s: “for the purposes of railway construction and other public works, to employ skilled and other labour, to build manufactories, lay out townships, construct waterworks, and waterways … to establish schools for elementary, technical, and scientific education, to publish newspapers, to aid in the organisation of the military forces of the Kingdom, and to assist the King in his Government…” This would have won Asante diplomatic recognition from the crown and allowed the kingdom to retain its autonomy while modernising its economy.5

But the Gold Coast authorities, who were already opposed to Asante’s resurgence under Prempeh and feared that the king would seek French protection to counteract the British, invaded the kingdom in January 1896 and deposed Prempeh.

Owusu Ansa in 1872, Basel Mission archives

In the case of Asante and similar kingdoms along Africa’s Atlantic coast, the modernisation effort was attempted by Africans who, despite their Western training and acculturation, advocated strongly for the continued independence of their homelands.

Their limited success, just like their peers in Egypt, Imerina, Ethiopia, and Zanzibar, can be attributed to a combination of European interference (ie, the colonial invasion itself), labour constraints, persistently high cost of capital, as well as internal resistance from traditionalists, whose motivations were equally complex.

In other regions, such as Central Africa, these western-educated Africans were instead shut out of local administration and were thus very critical of both the Portuguese colonial authorities in Luanda and African kingdoms like Kongo for their slow adoption of modernization.

As one visitor to the region in 1856 remarked:

“At that time, certain utopian ideas of independence were brewing in Luanda, with which some exalted sons of the country sought to free the motherland, as they called it, from Portuguese rule. There was talk of a republic, of an option for Brazilian nationality, and there were even those who considered making a gift from their beloved homeland to the Republic of the United States of America.”

Another traveller who visited the kingdom of Kongo in the same year met a ‘black gentleman’ who, despite elevating himself above his peers because of his western education in Luanda, was a “furious patriot.” The gentleman “railed against the Portuguese, who had ruined Kongo, against the whites who pushed their way into foreign lands, and declared that Africa would not improve until the last Portuguese had been thrown out.”

The most remarkable among the early modernisers of central Africa was Prince Nicolau (1830-1860), who was educated in Lisbon and later returned to Kongo, where he became the most vocal critic of the Portuguese colonialists in Luanda and of their ally, the Kongo king Pedro V (r. 1859-91), for signing a treaty of vassalage to the former.

Nicolau, who has been championed as one of Africa’s earliest nationalists in contrast to King Pedro, whom he derided as a dupe, represents the competing visions of modernisers and traditionalists which characterised the political debates of 19th-century Africa at the dawn of colonialism.

The competing ideologies of these 19th-century personalities in Kongo and their significance in the colonization of Africa, are the subject of my latest Patreon article.

Please subscribe to read more about it here, and support this newsletter:

On early European-African contacts during the age of mutual discovery, see: Europeans and Africans: Mutual Discoveries and First Encounters by Michał Tymowski. Africa's Discovery of Europe: 1450-1850 by David Northrup. On comparisons between an African and European kingdom in the 15th century, see the examples in the article cited and: Early Kongo-Portuguese Relations: A New Interpretation by John Thornton

For a good summary of early industrialization in Egypt, Imerina, and Ethiopia, see; Chapt. 10 of ‘Africa and the Indian Ocean World from Early Times to Circa 1900’ by Gwyn Campbell. on Ethiopia, see; “Tewodros as an Innovator” by R. Pahnkhurst, in, Kasa and Kasa: Papers on the Lives, Times and Images of Téwodros II and Yohannes IV (1855-1889), edited by Taddese Beyene, Richard Pankhurst, Shiferaw Bekele. on Egypt, see; Egypt in the Reign of Muhammad Ali by Afaf Lutfi Sayyid-Marsot. on Zanzibar, see; Chapt. 4 of ‘Domesticating the World: African Consumerism and the Genealogies of Globalization’ by Jeremy Prestholdt

Prince Owusu-Ansa of Asante, 1823-1884 by K Owusu-Mensa, pg 23-44, Asante in the Nineteenth Century: The Structure and Evolution of a Political Order by Ivor Wilks, pg 596-631,

Asante in the Nineteenth Century: The Structure and Evolution of a Political Order by Ivor Wilks, pg 632-636

Asante in the Nineteenth Century: The Structure and Evolution of a Political Order by Ivor Wilks, pg 651-652

This is great, thanks.

Thanks for sharing ..