The Mali empire: A complete history (ca. 1250-1650)

At its height in the 14th century, the Mali empire was one of Africa's largest states, extending over an estimated 1.2 million square kilometers in West Africa. Encompassing at least five modern African states, the empire produced some of the continent's most renowned historical figures like Mansa Musa and enabled the growth and expansion of many of the region's oldest cities like Timbuktu.

From the 13th century to the 17th century, the rulers, armies, and scholars of Mali shaped the political and social history of West Africa, leaving an indelible mark on internal and external accounts about the region, and greatly influenced the emergence of successor states and dynasties which claimed its mantle.

This article outlines the history of Mali from its founding in the early 13th century to its decline in the late 17th century, highlighting key events and personalities who played important roles in the rise and demise of Mali.

Map of Imperial Mali in the 14th century.1

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Background to the emergence of Mali: west Africa during the early 2nd millennium and the Sudiata epic.

The region where the Mali empire would emerge appears in some of the earliest accounts about West Africa, which locate it along the southern fringes of the Ghana empire. The 11th-century account of Al-Bakri mentions the “great kingdom” of Daw/Do along the southern banks of the Niger River, and another kingdom further to its south named Malal. He adds that the king of Malal adopted Islam from a local teacher, took on the name of al-Muslimânî and renounced the beliefs of his subjects, who “remained polytheists”.2

This short account provides a brief background on the diverse social landscape in which Mali emerged, between the emerging Muslim communities in the cities such as Jenne, and the largely non-Muslim societies in its hinterland. Archeological discoveries of terracotta sculptures from Jenne-Jeno and textiles from the Bandiagara plateau dated to between the 11th-15th centuries, in an area dotted with mosques and inscribed stele, attest to the cultural diversity of the region3. The complementary and at times conflicting accounts about Mali's early history were shaped by the divergent world views of both communities and their role in the emergence of Mali.

Written accounts penned by local West African scribes (especially in Timbuktu) and external writers offer abundant information on the kingdom’s Muslim provinces in its north and east but ignore the largely non-Muslim regions. Conversely, the oral accounts preserved by the non-Muslim jeli (griots), who were the spokespersons for the heads of aristocratic lineages and transmitted their histories in a consistent form, have very little to say about Muslim society of Mali, but more to say about its southern provinces. Both accounts however emphasize their importance to the royal court and the Mansas, leaving little doubt about their equal roles in Mali's political life.4

Equestrian figures of elite horsemen from Jenne-Jeno, ca 12th-14th century, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Werner Forman, Reclining figure from Jenne-Jeno, ca. 12th–14th century, Musée National du Mali

Tunic and Textile fragments from the "Tellem", 11th-12th century, Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen, and Musée National du Mali, Bamako

The foundational epic of Mali as recounted by the griots mentions several popular characters and places in the traditions of Mande-speaking groups, with a special focus on Sudianta, who was born to a king of Manden (a region straddling the border between modern Mali and Guniea) and a woman from the state of Do (Daw) named Sogolon. The succession of a different son of the king forced Sogolon and Sudianta to move from Manden to the region of Mema (in the central region of modern Mali), just as Manden was conquered by a king named Sumanguru. Sudianta later travels back to Manden, allies with neighboring chieftains, defeats Sumanguru, and assumes the throne as the first Mansa ( Sultan/King ) of Mali. Sunjata and his allies then undertake a series of campaigns that expand the embryonic empire.5

The cultural landscape of the epic is indisputably that of traditional Mandinka society which, for seven centuries, has developed, worked on, and transmitted to the present day a story relating to events of the 13th century. Despite the authoritative estimates provided in many recent accounts about Mali's history, the dates associated with the events in Sudianta's epic are heavily disputed and are at best vaguely assigned to the first half of the 13th century. However, the association of Sudianta with the creation of the empire's institutions such as the ‘Grand council’ of allied lineage heads, represents a historical reality of early Mali’s political history.6

Some of the archeological zones of the west African ‘sudan’ between the mid-3rd millennium BC and mid 2nd millennium AD.7

Map of early Mali in the 13th century

Mali in the 14th century: from Sudiata to Mansa Musa

That the founding and history of Mâli were remembered in what became its southwestern province of Manden was likely due to the province’s close relationship with the ruling dynasty, both in its early rise and its later demise. Outside the core of Manden, the ruler of Mâli was recognized as an overlord/suzerain of diverse societies that were incorporated into the empire but retained some of their pre-existing power. These traditional rulers found their authority closely checked by Mali officers called farba/farma/fari (governors), who regulated trade, security, and taxation. Because sovereignty was exercised at multiple scales, Mali is best described as an empire, with core regions such as Mande and Mema, and outlying provinces that included the former Ghana empire.8

It was from the region of the former Ghana empire that a scholar named Shaykh Uthman, who was on a pilgrimage to Cairo, met with and provided a detailed account of the Mansas to the historian Ibn Khaldun about a century and a half later. Uthman’s account credits the founding of the empire to Mârî Djâta, who, according to the description of his reign and his name, is to be identified with Sundiata.9

Sudianta was succeeded by Mansa Walī (Ali), who is described as "one of the greatest of their Kings", as he made the pilgrimage during the time of al-Zâhir Baybars (r. 1260-1277). Mansa Walī was later succeeded by his brothers Wâtî and Khalîfa, but the latter was deposed and succeeded by their nephew Mansa Abû Bakr. After him came Mansa Sakura, a freed slave who seized power and greatly extended the empire's borders from the ocean to the city of Gao. He also embarked on a pilgrimage between 1299-1309 but died on his way back. He was succeeded by Mansa Qû who was in turn succeeded by his son Mansa Muhammad b. Qû, before the throne was assumed by Mansa Musa (r. 1312–37), whose reign is better documented as a result of his famous pilgrimage to Mecca.10

Detail of the Catalan Atlas ca. 1375, showing King Mûsâ of Mâli represented in majesty carrying a golden ball in his hand. The legend in Catalan describes him as “the richest and noblest lord of all these regions”.

The royal pilgrimage has always been considered a vector of integration and legitimization of power in the Islamic world, fulfilling multiple objectives for both the pilgrims and their hosts. In West Africa, it was simultaneously a tool of internal and external legitimation as well as a tool for expanding commercial and intellectual links with the rest of the Muslim world. In Mali, the royal pilgrimage had its ascendants in the pre-existing traditions of legitimation and the creation of political alliances through traveling across a ‘sacred geography’.11

The famous account of Mansa Musa's predecessor failing at his own expedition across the Atlantic is to be contrasted with Mansa Musa's successful expedition to Mecca which was equally extravagant but was also deemed pious. More importantly, Mansa Musa's story of his predecessor's demise explains a major dynastic change that allowed his 'house' —descended from Sudianta's brother Abû Bakr— to take the throne.12

Mansa Musa returned to Mali through the city of Gao which had been conquered by Mali during Mansa Sakura’s reign, but is nonetheless presented in later internal sources as having submitted peacefully. Mansa Musa constructed the Jingereber mosque of Timbuktu as well as a palace at the still unidentified capital of the empire. His entourage included scholars and merchants from Egypt and the Hejaz who settled in the intellectual capitals of Mali.13 Some of the Malian companions of Musa on his pilgrimage returned to occupy important offices in Mali, and at least four prominent ‘Hajjs’ were met by the globe-trotter Ibn Battuta during his visit to Mali about 30 years later .14

According to an account provided to al-‘Umarī by a merchant who lived in Mali during the reign of Mansa Musa and his successors, the empire was organized into fourteen provinces that included Ghana, Zafun (Diafunu), Kawkaw (Gao), Dia (Diakha), Kābara, and Mali among others. Adding that in the northern provinces of Mali “are tribes of ‘white’ Berbers under the rule of its sultan, namely: the Yantaṣar, Tīn Gharās, Madūsa, and Lamtūna” and that “The province of Mali is where the king’s capital, ‘Byty’, is situated. All these provinces are subordinate to it and the same name Mālī, that of the chief province of this kingdom, is given to them collectively.15” Later internal accounts from Timbuktu corroborate this account, describing provinces and towns as the basis of Mali's administration under the control of different officers, with a particular focus on cities such as Walata, Jenne, Timbuktu, and Gao.16

The Djinguereber Mosque in Timbuktu, the original structure was commissioned by Mansa Musa in 132517

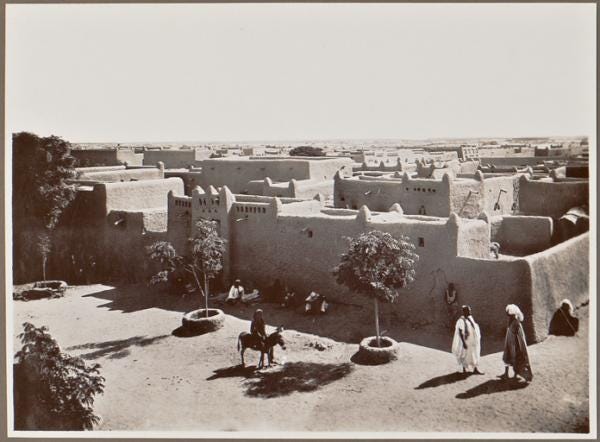

The city of Gao, ca. 1920, archives nationales d'outre mer.

Mali under Mansa Musa and Mansa Sulayman

It’s from Gao that another Malian informant of Ibn Khaldun named Abû AbdAllah, a qadi of the city, provided an account of the 14th-century rulers of Mali that ended with the 'restoration' of the old house and the deposition of Abu Bakr's house. The rivalry between the two dynastic houses may explain the relative 'silence' in oral accounts regarding the reigns of the Abu Bakr house, especially Mansa Musa and his later successor Mansa Sulayman (r. 1341–60), who was visited by Ibn Battuta in 1352.18

Ibn Battuta’s account includes a description of Mansa Sulayman's court and an outline of the administrative structure of the empire, mentioning offices and institutions that appear in the later Timbuktu chronicles about Mali's successor, the Songhai empire. He mentions the role of the Queen, who is ranked equal to the emperor, the nâ'ib, who is a deputy of the emperor, a royal guard that included mamluks (slaves bought from Egypt), the griots who recounted the history of his predecessors, the farba (governors), the farâriyya, a term for both civil administrators and military officers, as well as a litany of offices such as the qadis (judges), the mushrif/manshājū who regulated markets, and the faqihs (juriconsult) who represented the different constituencies.19

Ibn Battuta's account also highlights the duality of Mali's social-political structure when the King who had earlier been celebrating the Eid festival as both a political and religious event in the presence of his Muslim subjects and courtiers, but was later a central figure of another important festival by Mali's non-Muslim griots and other subjects, the former of whom wore facemasks in honor of the ancestral kings and their associated histories. The seemingly contradictory facets of Mali's political spaces were in fact complementary.20

Mansa Musa initiated diplomatic relations with the Marinid sultanate of Fez (Morocco) during the reign of Abū ’l-Ḥasan (r. 1331–1348) that would be continued by his successors. During Mansa Musa’s reign, “high ranking statesmen of the two kingdoms were exchanged as ambassadors”. and Abū ‘l-Ḥasan sent back “novelties of his kingdom as people spoke of for long after”. The latter’s embassy was received by Mansa Sulayman, who reciprocated by sending a delegation in 1349, shortly before Ibn Battuta departed from Fez to arrive at his court in 1852.21

Ibn Battuta remarked about an internal conflict between Sulaymân and his wife, Queen Qâsâ, who attempted to depose Sulayman and install a rival named Djâtil, who unlike Mansa Musa and Sulayman, was a direct descendant of Sudianta. The Queen's plot may have failed to depose the house of Abu Bakr whose candidates remained on the throne until 1390, but this dynastic conflict prefigured the succession crises that would plague later rulers.22

After his death in 1360, Sulayman was briefly succeeded by Qāsā b. Sulaymān, who was possibly the king's son or the queen herself acting as a regent. Qasa was succeeded by Mārī Jāṭā b. Mansā Maghā (r. 1360-1373), who sent an embassy to the Marinid sultan in 1360 with gifts that included a “huge creature which provoked astonishment in the Magrib, known as the giraffe”23. He reportedly ruined the empire before his son and successor Mansa Mūsā II (r. 1373-1387) restored it. Musa II’s wazir (high-ranking minister) named Mārī Jāṭā campaigned extensively in the eastern regions of Gao and Takedda. After he died in 1387, Mūsā II was briefly succeeded by Mansā Maghā before the latter was deposed by his wazir named Sandakī. The latter was later deposed by Mansa Maḥmūd who restored the house of Sudiata with support from Mali’s non-Muslim provinces in the south.24

The intellectual landscape of Mali.

Regarding the early 15th century, most accounts about Mali focus on the activities of its merchants and scholars across Mali's territories, especially the Juula/Dyuula who'd remain prominent in West Africa's intellectual traditions

The Mali empire had emerged within an already established intellectual network evidenced by the inscribed stele found across the region from Ghana's capital Kumbi Saleh to the city of Gao beginning in the 12th century. Mali's elites and subjects could produce written documents, some of which were preserved in the region's private libraries, such as Djenne's oldest manuscript dated to 1394.25 Additionally, the Juula/Jakhanke/Wangara scholars whose intellectual centers of Diakha and Kabara were located within the Mali empire’s heartland spread their scholarly traditions to Timbuktu, producing prominent scholars like Modibo Muḥammad al-Kābarī, whose oldest work is dated to 145026.

While writing wasn’t extensively used in administrative correspondence within Mali, the rulers of Mali were familiar with the standard practices of written correspondence between royals which required a chancery with a secretary. For example, al-‘Umarī mentions a letter from Mansa Mūsā to the Mamluk ruler of Cairo, that was “written in the Maghribī style… it follows its own rules of composition although observing the demands of propriety”. It was written by the hand of one of his courtiers who had come of the pilgrimage. Its contents comprised of greetings and a recommendation for the bearer,” and a gift of five thousand mithqāls of gold.27

About a century later, another ruler of Mali sent an ambassador to Cairo in order to inform the latter’s ruler of his intention to travel to Mecca via Egypt. After the ambassador had completed his pilgrimage, he returned to Cairo in July 1440 to receive a written response from the Mamluk sultan. The Mamluk letter to Mali, which has recently been studied, indicates that the sultan granted Mansa Yusuf's requests, writing: "For all his requests, we have responded to his Excellency and we have issued him a noble decree for this purpose."According to the manual of al-Saḥmāwī, who wrote in 1442, the ruler of Mali at the time was Mansa Yūsuf b. Mūsā b. ʿAlī b. Ibrahim.28

'Garden of Excellences and Benefits in the Science of Medicine and Secrets' by Modibbo Muhammad al-Kābarī, ca. 1450, Timbuktu, Northwestern University

An empire in decline: Mali during the rise of Songhai in the 16th century.

It’s unclear whether Mansa Yusuf succeeded in undertaking the pilgrimage since the last of the royal pilgrimages from Takrur (either Mali or Bornu) during the 15th century occurred in 143129. Mali had lost control of Timbuktu to the Maghsharan Tuareg around 1433 according to Ta’rīkh as-sūdān, a 17th century Timbuktu chronicle. Most local authorities from the Mali era were nevertheless retained such as the qadis and imams. The Tuareg control of Timbuktu ended with the expansion of the Songhai empire under Sunni Ali (r. 1464-1492), who rapidly conquered the eastern and northern provinces of Mali, including Gao, Timbuktu, Jenne, and Walata.30

The account of the Genoese traveler Antonio Malfante who was in Tuwat (southern Algeria) around 1447 indicates that Gao, Timbuktu, and Jenne were separate polities from Mali which was “said to have nine towns.” A Portuguese account from 1455-56 indicates that the “Emperor of Melli” still controlled parts of the region along the Atlantic coast, but mentions reports of war in Mali's eastern provinces involving the rulers of Gao and Jenne.31

Mali in the 16th century

Between 1481 and 1495, King John II of Portugal sent embassies to the king of Timbuktu (presumably Songhai), and the king of Takrur (Mali). The first embassy departed from the Gambia region but failed to reach Timbuktu, with only one among the 8-member team surviving the journey. A second embassy was sent from the Portuguese fort at El-Mina (in modern Ghana), destined for Mali, after the gold exports from Mali’s Juula traders at El-mina had alerted the Portuguese to the empire’s importance.

The sovereign who received the Portuguese delegation was Mansa Maḥmūd b. Walī b. Mūsā, the grandson of the Mansa Musa II (r. I373/4 to I387). According to the Portuguese account; "This Moorish king, in reply to our King's message, amazed at this novelty [of the embassy] said that none of the four thousand four hundred and four kings from whom he descended, had received a message or had seen a messenger of a Christian king, nor had he heard of more powerful kings than these four: the King of Alimaem [Yemen], the King of Baldac [Baghdad], the King of Cairo, and the King of Tucurol [Takrur, ie; Mali itself]"32

While no account of the envoys' negotiations at the capital of Mali was recorded, it seems that later Malian rulers weren’t too receptive to the overtures of the Portuguese, as no further delegations were sent by the crown, but instead, one embassy was sent by the El-mina captain Joao Da Barros in 1534 to the grandson of the abovementioned Mansa. By then, the gold trade of the Juula to el-Mina had declined from 22,500 ounces a year in 1494, to 6,000 ounces a year by 1550, as much of it was redirected northwards.33

Between the late 15th and mid 16th century, the emergence of independent dynasties such as the Askiya of Songhai and the Tengella of Futa Toro challenged Mali's control of its northern provinces, and several battles were fought in the region between the three powers. Between 1501 and 1507, Mali lost its northern provinces of Baghana, Dialan, and Kalanbut to Songhai, just as the regions of Masina and Futa Toro in the northwest fell to the Tengella rulers and other local potentates.34

Mali became a refuge for rebellious Songhai royals such as Askiya Muḥammad Bonkana Kirya who was deposed in 1537. He moved to Mali’s domains where his son was later married. But the deposed Aksiya and his family were reportedly treated poorly in Mali, forcing some of his companions to depart for Walata (which was under Songhai control) while the Bonkana himself remained within Mali’s confines in the region of Kala, west of Jenne35. It’s shortly after this that in 1534 Mansa Mahmud III received a mission from the Elmina captain Joâo de Barros, to negotiate with the Mali ruler on various questions concerning trade on the River Gambia.36

Mali remained a major threat to Songhai and often undertook campaigns against it in the region west of Jenne. In 1544 the Songhai general (and later Askiya) Dawud, led an expedition against Mali but found the capital deserted, so his armies occupied it for a week. Dawud's armies would clash with Mali's forces repeatedly in 1558 and 1570, resulting in a significant weakening of Mali and ending its threat to Songhai. The ruler of Mali married off his princess to the Askiya in acknowledgment of Songhai’s suzerainty over Mali37

Jenne street scene, ca. 1906.

From empire to kingdom: the fall of Mali in the 17th century.

Songhai’s brief suzerainty over Mali ended after the collapse of Songhai in 1591, to the Moroccan forces of al-Mansur. The latter attempted to pacify Jenne and its hinterland, but their attacks were repelled by the rulers of Kala (a Bambara state) and Massina, who had thrown off Mali’s suzerainty. The Mali ruler Mahmud IV invaded Jenne in 1599 with a coalition that included the rulers of Masina and Kala, but Mali's forces were driven back by a coalition of forces led by the Arma and the Jenne-koi as well as a ruler of Kala, the last of whom betrayed Mahmud but spared his life..38

While Mali had long held onto its western provinces along the Gambia River, the emergence of the growth of the kingdom of Salum as a semi-autonomous polity in the 16th century eroded Mali's control over the region and led to the emergence of other independent polities. By 1620, a visiting merchant reported that the Malian province had been replaced by the kingdoms of Salum, Wuli, and Cayor.39

Over the course of the early 17th century, Mali lost its suzerainty over the remaining provinces and was reduced to a small kingdom made up of five provinces that were largely autonomous. Mali’s power was eventually eclipsed by the Bambara empire of Segu which subsumed the region of Manden in the late 17th century, marking the end of the empire.40

The Palace of Amadu Tal in Segou, late 19th century illustration after it was taken by the French

In the Hausaland region (east of Mali) two ambitious Hausa travelers explored Western Europe from 1852-1856, journeying through Malta, France, England, and Prussia (Germany). Read about their fascinating account of European society here

Map by Michael Gomez

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 18-19

Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara by Alisa LaGamma pg 48-78

The imperial capital of Mâli François-Xavier Fauvelle prg 7, Les masques et la mosquée - L'empire du Mâli by François-Xavier Fauvelle pg 53

In Search of Sunjata: The Mande Oral Epic as History, Literature and Performance edited by Ralph A. Austen

African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa By Michael A. Gomez pg 62-63, Les masques et la mosquée - L'empire du Mâli by François-Xavier Fauvelle pg *51, *30-34

Map by Roderick McIntosh

The imperial capital of Mâli François-Xavier Fauvelle prg 8)

African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa By Michael A. Gomez pg 69, 82, 84, 87. In Search of Sunjata: The Mande Oral Epic as History, Literature and Performance edited by Ralph A. Austen pg 48

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 93-94 African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa By Michael A. Gomez pg 96-99)

Le Mali et la mer (XIVe siècle) by François-Xavier Fauvelle

Les masques et la mosquée - L'empire du Mâli by François-Xavier Fauvelle pg *64-65, African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa By Michael A. Gomez pg 124-125)

Travels of Ibn Battuta Vol4 pg 951-952, 956, 967, 970-971

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 53-54

African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa By Michael A. Gomez pg 126-129

The great mosque of Timbuktu by Bertrand Poissonnier pg 31-34

Les masques et la mosquée - L'empire du Mâli by François-Xavier Fauvelle pg *140-145)

Les masques et la mosquée - L'empire du Mâli by François-Xavier Fauvelle pg *145-156, African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa By Michael A. Gomez pg 139-141)

Les masques et la mosquée - L'empire du Mâli by François-Xavier Fauvelle pp. 211-225)

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 95, 100

African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa By Michael A. Gomez pg 148-149)

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 96

African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa By Michael A. Gomez pg 150-151, Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 97-98

From Dust to Digital: Ten Years of the Endangered Archives Programme, 2015, pg 173-188

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 63-64

Ressusciter l’archive. Reconstruction et histoire d’une lettre mamelouke pour le sultan du Takrūr (1440) by Rémi Dewière

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 118

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 30-31, African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa By Michael A. Gomez pg 183-185)

African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa By Michael A. Gomez pg 151-153.)

Wangara, Akan and Portuguese I by Ivor Wilks pg 338-339, D’ Asia by João de Barros pg 260-261.

Wangara, Akan and Portuguese II by Ivor Wilks, pg 465-6

General History of Africa Volume IV by UNESCO pg 180-182, Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 108-110, 113

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 134-135

African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa By Michael A. Gomez, pg 207

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 140, 148, 153-154,

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 234-236)

General History of Africa Volume IV by UNESCO pg 183-184)

General History of Africa Volume IV by UNESCO pg 184, The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 4 pg 171-174

(* are not the exact page numbers)