The medieval Knights of Ethiopia: a history of the Horse in the northern Horn of Africa (1000-1900CE)

Pre-colonial Africa was home to some of the oldest and most diverse equestrian societies in the world. From the ancient horsemen of Kush to the medieval Knights of West Africa and the cavaliers of Southern Africa, horses have played a significant role in shaping the continent's political and social history.

In Ethiopia, the introduction of the horse during the Middle Ages profoundly influenced the structure of military systems in the societies of the northern Horn of Africa, resulting in the creation of some of Africa's largest and most powerful cavalries.

As distinctive symbols of social status, horses were central to the aristocratic image of rulers and elites in medieval Ethiopia, while as weapons of war, they changed the face of battle and the region’s social landscape. Today, the horse remains the most culturally respected and highly valued domestic animal in Ethiopia, and the country is home to Africa's largest horse population.

This article explores the history of the horse in the kingdoms and empires of Ethiopia since the Middle Ages, and the development of the country’s diverse equestrian traditions.

Map showing some of the societies in northeastern Africa at the end of the 16th century.1

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Historical background: horses and cavalries in Ethiopia until the 16th century

The first equids used by the ancient societies of north-east Africa were donkeys, which were domesticated in the region around 2500BC, while horses were introduced later by 1500BC.2

A few equid remains are represented in small numbers in the faunal assemblages of Aksum, but their exact identification remains problematic since none of the archaeozoological specimens has been precisely identified at the species level. According to the archaeologist David Phillipson, there is no convincing evidence that horses were exploited in the Aksumite kingdom.3

Horses first appear in Ethiopia's historical record in the late Middle Ages, during the Zagwe period (ca. 1150-1270CE). There are a handful of representations of horses on the western porch of Betä Maryam church of Lalibäla, consisting of sculptures in low relief showing horsemen hunting real and mythological animals.4 Envoys from the Egyptian Coptic patriarch during the reign of Lalibela mention that the Zagwe monarch had a large army, consisting of an estimated 60,000 mounted soldiers, not counting the numerous servants who followed them.5

In the area east and south of Lalibäla, three churches display on their walls paintings associated with Yǝkunno Amlak (r. 1270–1285), who overthrew the Zagwe rulers and founded the Solomonic dynasty of the Christian kingdom. One of the paintings in the vestibule of the rock-hewn church of Gännätä Maryam depicts a certain prince named Kwəleṣewon on a horse, in a style of royal iconography that would become common during later periods.6

(left) Horse tracks on the wall of Biete Giyorgis church, Lalibela, Ethiopia. Smithsonian National Museum of African Art. The church is dated to the 14th-15th century. (right) Mural depicting the Wise Virgins (upper register) and prince Kwəleṣewon with his mother Təhrəyännä Maryam (lower register), church of Gännätä Maryam ca. 1270–85. image by Claire Bosc-Tiessé.

A letter from Yǝkunno Amlak to the Mamluk Egyptian Sultan Baybars (r. 1260-77), mentions that the large army of the Ethiopian monarch included a hundred thousand Muslim cavaliers. The above estimates of the cavalries of king Lalibela and Yǝkunno Amlak were certainly exaggerated, but indicate that mounted soldiers were already part of the military systems of societies in the northern Horn of Africa by the 13th century.7

By the reign of ʿAmdä Ṣǝyon, the Solomonid monarchs of Ethiopia had built up a large cavalry force, mostly raised from the provinces of Goǧǧam and Damot. The King's chronicle mentions that in response to a rebellion in 1332, “He sent other contingents called Damot, Seqelt, Gonder, and Hadya (consisting of) mounted soldiers and footmen and well trained in warfare...”8

Mamluk records from the early 15th century, which describe the activities of the Persian merchant called al-Tabrīzī, mention horses and arms among the trade items exported from Egypt to Ethiopia through the Muslim kingdoms of the region.9

The account of Ibn Fadl Allah, written between 1342 and 1349, lists the armed forces of Ethiopia’s Muslim sultanates: Hadya, ‘the most powerful of all’, had 40,000 horsemen and ‘an immense number of infantry’. Ifat and Dawaro had each about 15,000 horsemen and 20,000 foot soldiers, Bali 18,000 horsemen and a mass of footmen, Arababni nearly 10,000 cavalry and ‘very numerous’ infantry, Sharkha 3,000 horsemen and at least twice that number of infantry, and Dara, the weakest province, 2,000 horse and as many in the infantry.10

However, these figures were likely inflated since internal accounts and accounts by later visitors to the region provide much lower estimates, especially for the cavalries of the Adal empire, which united these various Muslim polities in the 15th century and imported horses from Yemen and Arabia.

During the Adal invasion of Ethiopia in 1529, at the decisive battle of ShemberaKure, the Adal general Imam Ahmad Gran had an army of 560 horsemen and 12,000-foot soldiers, while the Ethiopian army was made up of 16,000 horsemen and more than 200,000 infantry; according to the Muslim chronicler of the wars. Ethiopian accounts, on the other hand, put the invading forces at 300 horsemen and very few infantry, and their own forces at over 3,000 horsemen and ‘innumerable’ foot-men.11

(left) Abyssinian Warriors ca. 1930. Mary Evans Picture Library. (right) Horseman from Harar. ca. 1920, Smithsonian National Museum of African Art

As for the cavalries forces of the southern regions, the 1592 account of Abba Baḥrǝy notes that the Oromo ruler luba mesele (Michelle Gada, r. 1554-1562) “began the custom of riding horses and mules, which the [Oromo] had not done previously.” However, it’s likely that the Oromo began using horses much earlier than this, but hadn't deployed them in battle since their early campaigns mostly consisted of nighttime guerrilla attacks, which made horses less important.12

Oromo moieties of the Borana and Barentu quickly formed cavalry units, which enabled them to rapidly expand their areas of influence over much of the horse-rich southern half of the territories controlled by the Gondarine kingdom of Ethiopia as well as parts of the Muslim kingdom of Adal.13 According to Pedro Páez, after the Oromo attacked Gojjam, Sarsa Dengel thought it best to excuse the tribute of 3,000 so that the inhabitants of Gojjam could use the horses to defend themselves.14

By the close of the 16th century, most of the armies of the northern horn of Africa had large cavalry units.

St George slaying dragon next to the Madonna and Child, Fresco from the 18th-century church of Debre Birhan Selassie Church, Gondar, Amhara, Ethiopia.

Horse trade and breeding in Ethiopia from the Middle Ages to the 19th century

Historical evidence indicates that Ethiopia was both an exporter and importer of horses since the middle ages.

A Ge'ez medieval work describing the 14th century period, mentions that Ethiopian Muslim merchants “did business in India, Egypt, and among the people of Greece with the money of the King. He gave them ivory, and excellent horses from Shewa... and these Muslims...went to Egypt, Greece, and Rome and exchanged them for very rich damasks adorned with green and scarlet stones and with the leaves of red gold, which they brought to the king.”15

The coastal towns of Zeila and Berbera in Somaliland, which served as the main outlet of Ethiopian trade during the Middle Ages, were also renowned for their horse exports. In his 14th-century account, Ibn Said described Zeila as an export center for captives and horses from Abyssinia, while Barbosa in the 16th century describes Zeila as ‘a well-built place’ with ‘many horses.’16

Similarly, the port of Berbera was renowned also for its horses which enjoyed a great reputation among the Arabs; the Arab writer Imrolkais emphasizes the quality of the local horses in telling the imaginary story of a noble steed from there that journeyed from the Roman Empire to Arabia. The account of the portuguese Tome Pires, which describes the period from 1512 to 1515, mentions that “The principal Abyssinian merchandise were gold, ivory, horses, slaves, and foodstuffs” exported through Zeila and Berbera.17

Horses were part of the tribute levied on some Ethiopian provinces, especially those in the southwest such as Gojjam. One of the Amharic royal songs in honor of the Emperor Yǝsḥaq (r. 1414–29) lists the southern provinces with their tribute in kind: gold, horses, cotton, etc. Portuguese accounts from the 16th century also mention that the tribute from Gojjam amounted to 3000 mules, 3000 horses, and 3000 large cotton garments.18

The same accounts also mention that horses were received as tribute from Tigray, but many of these appear to have been imported from Egypt and Arabia and were said to be larger than those from Gojjam, implying that the latter were local breeds. The chronicle of Emperor Sartsa Dengel (r. 1563-1597), also notes that the tribute of the Bahr Negash (governor of the coastal region) was composed of large numbers of imported silks and cloth, china ware, and excellent horses.19

Ethiopian rider, illustration by Charles-Xavier Rochet d'Héricourt, ca. 1841.

The 16th-century Portuguese traveler Francesco Alvares also mentions that “many lords breed horses from the mares they get from Egypt in their stables.”20 17th-century Portuguese accounts mention that the best of the imported breeds were bought in the hundreds from the kingdom of Dequin, located between Ethiopia and the Funj kingdom of Sennar: these were the famous Dongola horses that were exported across west Africa. (James Bruce mentions that Dongola horses were about 16.5 hands tall). Later accounts from the 17th century note that these breeds were crossed with horses from Tigray and Serae (in Eritrea) to supply the Emperor's stables.21

Pedro Páez 1622 account mentions that large horses imported from Dequin (in Sudan) didn’t last long in Ethiopia “because they develop sores on their feet, from which they die. The other horses in the empire are commonly small but strong and run fast” and that disputes between the two kingdoms often threatened the lucrative horse trade.22 It is thus likely that the crossbreeding mentioned above was in response to this challenge. Additionally, the breakdown of trade between Ethiopia and the Funj kingdom (which was the suzerain of Dequin) in the 18th century forced the Ethiopians to breed their own horses in the less-than-ideal conditions of the highlands.23

In the 18th century, the regions of Damot and Gojjam were still an important source of horses and horsemen for the Christian kingdom. Internal markets for horses emerged in several trading settlements such as Makina in Lasta, Sanka in Yeju, Cäcaho in Bagémder, Yefag in Dembya, Gui in Gojam, and Bollo-Worké in Shewa.24

During this period, horses were included among both the exports and imports to the Muslim kingdoms of Sudan, especially through the border town of Matemma. This was because the Sudanese region of Barca, east Sennar, and Dongola produced fine horses much sought after in Ethiopia for breeding purposes, while the Ethiopian horses were much cheaper than those of the Sudan and were hence in considerable demand across the frontier.25

Abyssinian troops in the field. image from "Voyage en Abyssinie", 1839-1843, by Charlemagne Theophile Lefebvre, Ethiopia.

Ethiopian horses were also exported to the Red Sea region, ultimately destined for markets in the western Indian Ocean. An estimated 150 to 200 horses were sold in the market of Galabat, which were then exported through the Red Sea port of Suakin. Merchants from the city of Gondar also traveled to the port town of Berbera in Somaliland, to export horses, ivory, and captives, which were exchanged for cotton cloths and Indian goods.26

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the region of Wallo and Agaw Meder in Gojjam were major centers of horse breeding. The region of Agaw Meder in Gojjam was also noted for its production of pack animals. The inhabitants of Agaw Meder bred mare horses and donkey stallions, producing plenty of excellent mules and ponies. In the early 20th century horses of Agaw Meder were in high demand by government officials in the British Sudan, who used them to patrol the frontier.27

Today, there are eight different breeds of horses in Ethiopia: Abyssinian, Bale, Boran, Horro, Kafa, Ogaden/Wilwal, Selale, and the Kundido feral horse, with a probable ninth breed known as the Gesha horse. Ethiopian horses have a mean height of 12-13 hands, making them smaller than those in Lesotho and West Africa (13-14 hands), and Sudan (14-17 hands). The tallest Ethiopian breed is the Selale horse —also known as the Oromo horse, which is used as a riding horse. The rest of the breeds serve multiple functions, typically in agricultural work and rural transport.28

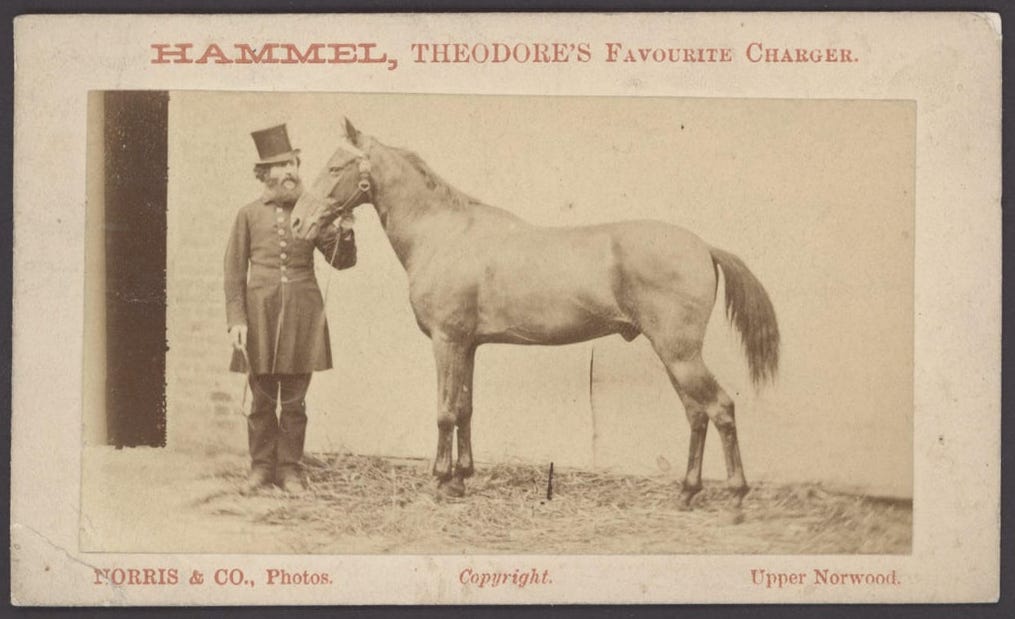

Hammel; the horse of emperor Tewodros II that was captured by the British after the battle of Magdala in 1868

Cavalry warfare in medieval and early modern Ethiopia

The core of Ethiopia's army, as in medieval Europe, was composed of horsemen.

Fighting was for the most part conducted with considerable chivalry. Descriptions of Ethiopian battles in the early 19th century (*between culturally similar regions) mention that exchanges of civilities would constantly take place between hostile camps, messengers were respected, and prisoners were “generally well treated, if of any rank, even with courtesy.” During the actual combat, “the horsemen would charge in large or small numbers when and where they thought fit.” Battles were decided within a few hours, and the victors often took loot which included the enemy's horses.29

A separate cavalry tradition was developed by the Oromo who organized cavalry formations and cultivated vital skills through frequent drilling. Young men grew up practicing throwing spears as well as riding horses in order to become formidable horsemen. Unlike the armies of the Solomonids, however, the Oromo cavalries were highly mobile and relied on guerrilla tactics in combat. According to a 17th-century Portuguese account:

“As soon as the [Oromo] perceive an enemy comes on with a powerful army they retire to the farther parts of the country, with all their cattle, the Abyssinians must of necessity either turn back or perish. This is an odd way of making war wherein by flying they overcome the conquerors; and without drawing sword oblige them to encounter with hunger, which is an invincible enemy.”30

‘Cavalry going into battle, with spears and shields’ ca. 1721-c1730. From the ‘Nagara Maryam’ manuscript. Heritage Images

‘Fit Aurari Zogo attacking a foot soldier.’ Tigray, Ethiopia. ca. 1809. Engraving by Henry Salt.

Emperor Susenyos (r. 1607-1632), who had been raised among the Oromo, quickly adopted their mode of fighting and used it to great effect against internal enemies and the Oromo cavalries, some of whom he allied with and integrated into his own forces. Susenyos and his successors were however unable to gain a decisive advantage over the Oromo cavalries, who in the 18th century, managed to establish strong polities in regions like Wallo that were defended by powerful armies with up to 50,000 horsemen.31

The horse-riding Awi Agaw groups, who lived in the Gojjam region, also raised large armies of horsemen who battled with the Gondarine monarchs of the Christian Kingdom and the Oromo cavalries during the 16th and 17th centuries. The Scottish traveler James Bruce mentions lineages of the ‘Agows’ such as the “Zeegam and Quaquera, the first of which, from its power arising from the populous state of the country, and the number of horses it breeds, seems to have no reason to fear the irregular invasions of [the Oromo]”32

In the mid-16th century, Galawdewos’ army consisted of only 20,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry, but by the 17th century, Emperor Susneyos could field “30,000 to 40,000 soldiers, 4,000 or 5,000 on horseback and the rest on foot. Of the horses up to 1,500 may be jennets of quality, some of them very handsome and strong, the rest jades and nags. Of these horsemen as many as 700 or 800 wear coats of mail and helmets.”33

During the 18th century, the main Ethiopian army consisted of four regiments which were named after “houses” of about 2,000 men each, of which 500 were horsemen. The royal cavalry consisted of Sanqella, from the west of the capital. They wore coats-of-mail, and the faces of their horses were protected with plates of brass with sharp iron spikes, and the horses were covered with quilted cotton armor. The stirrups were of the Turkish type which held the whole foot, rather than only one or toes as was common in Ethiopia. Each rider was armed with a 14ft long lance and equipped with a small axe and a helmet made of copper or tin.34

(left) St Fasilidas on a horse covered with quilted cotton armour. Mural from the church of Selassie Chelekot near Mekele, Tigray, Ethiopia. image by María-José Friedlander35 Quilted horse armour used by Mahdists of Sudan. 19th century. British Museum.

Horse equipment was mostly made by local craftsmen since the middle ages. The 14th-century monarch ʿAmdä Ṣǝyon is said to have formally organized in his court fifteen ‘houses’ each of which had its special responsibility. At least three of them looked after his defensive armor, his various other weapons of war, and the fittings of the horses.36

In the 16th century, Emperor Lebna Dengel employed several Muslim tailors at the royal capital of Barara in Shewa, where they made coverings for the royal horses. Later accounts from the 19th century indicate that all the horse equipment and paraphernalia used in the region were made by local craftsmen.37

A notable feature of Ethiopia's equestrian culture is the traditional stirrup which was thin and narrow, riders thus grasped the iron ring of the saddle with their big and index toe.38 During military parades when everyone displayed their horsemanship, warriors showed off their horse's maneuverability in galloping (gilbiya) and in parading (somsoma). Managing horse, shield, and spear while charging and retreating as necessary during a fight was admired.39

St. Fasiladas (left) and St. George (right), showing the two different types of stirrups known in Gondar in this period: one holding two toes, the other the whole foot. From an 18th century Miracles of Mary, in the Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris, Ethiopien d'Abbadie 222

By the 19th century, Ethiopian infantry and cavalry were primarily armed with spears and shields, while firearms and swords were also carried by persons of note. The largest number of horses were found in the southern pastoral lands of the Oromo. Possession of a steed was a sign of distinction, implying that its owner was a nobleman or man of substance, or else that he had distinguished himself in war, and had received one as a gift from his chief. A soldier's horse, mule, and weapons, however acquired, were invariably considered as his personal property.40

In the eastern regions between Harar and Somaliland, large cavalries disappeared after the fall of the Adal empire, and the number of warhorses fell. According to the account of Richard Burton who visited Harar in 1855, the city had just 30 warhorses, which were small but well suited for the mountainous region. He mentions that the neighboring Somali horses were of the same size, about 13 hands tall, and were also used in fighting, but none of the societies in western Somaliland during the 19th century were large enough to command a sizeable cavalry force, since most lived in nomadic communities.41

In the second half of the 19th century, the Ethiopian cavalry proved decisive against the Egyptians at the battle of Gura in 1876 as observed by the Egyptian contract officer Max von Thurneyssen who noted the superiority of Emperor Yohannes IV’s Oromo cavalry over their Egyptian counterparts. However, while Yohannes’ successor Menelik II was also able to field 40,000 horsemen in 1882, he was able to raise no more than 8,000 in 1896 due to the rinderpest epidemic.

Despite such losses, Menelik’s army of the 1890s was mainly armed with modern rifles, allowing it to prevail over the Italian colonial army at the famous battle Adwa, with the cavalry delivering shock attacks on the retreating enemy.42

Detail of a mural depicting Ethiopians going into battle against the Egyptians from the church of Abreha Atsbeha, Tigray, Ethiopia. (top register; left to right) in the top at the center is the crowned Emperor Yohannes IV on a horse, the next mounted figure is the Etege, and in front of the Etege is the mounted Abuna Atnatewos (1870-6), holding a hand-cross in his right hand, he died in battle. (bottom register: left to right) three mounted figures; the Nebura’ed Tedla, who was one of the commanders. In front of him is Emperor Yohannes IV, galloping into action, and, on the right is Emperor Yohannes IV’s brother, Dejazmach Maru, who occasionally commanded one of his armies.43

Abyssinian horse-soldier. Illustration for ‘The World Its Cities and Peoples by Robert Brown’. ca. 1885

The cultural significance of the horse in Ethiopia

The Ethiopian custom of calling royals and other elites after the names of the horses they rode, is arguably the most characteristic feature of the region's equestrian tradition.

The custom is attested in both the Oromo polities and the Christian kingdom, and likely originated from the former, who gained influence at the Gondarine court during the 18th century. Emperor Iyasu II (r. 1755-1768) is said to have erected a mausoleum for his horse called Qälbi, which is suggested to be the Afan Oromo word qälbi, for a ‘Cautious One.’ The late 18th-century Scottish traveler James Bruce also mentioned the use of horse names by Ethiopian noblemen and mentioned that he was treated with great respect by the local inhabitants because he was riding a gift horse given to him by the Oromo governor of Gojjam.44

By the 19th century, the custom of horse names had spread across the entire region. In Tigray during the early 19th century, the English traveler Nathaniel Pearce mentions that several of the most important chiefs had epithets “taken from the first horse which they ride on to war in their youth.” In his 1842 account, John Krapft observed that “it is customary in Abyssinia, particularly among the Oromo, to call a chieftain according to the name of his horse.” Horse names were common among the elites of Wallo, Shewa, Bagemder, Samen, Lasta, and Gojjam, as well as the southern polities of Hirmata-Abba Jifar, and Limmu-Enarya.45

Ethiopian artwork was also influenced by its equestrian tradition, especially in the representation of warrior saints and royals as mounted knights. The iconography of equestrian saints, which developed in the Byzantine Empire based on antique triumphal imagery, was adapted to Ethiopia’s cultural environment during the Middle Ages with slight modifications.46

The paintings often depict religious scenes with known figures such as St. George, St. St Mercurius, St. Téwodros (Theodore), St. Gelawdewos (Claudius), St. Fikitor (Victor), St. Qeddus Fasilidas (Basilides), St Filotewos (Philoteus), St Aboli, St Fasilidas, Susenyos, St. Gabra Krestos and others. These are usually shown accompanying kings, queens, and other notables on horseback.47

from left to right: Mercurius, with, in a small frame above his horse's head, St Basil and St Gregory; Eusebius (son of St Basilides the Martyr); Claudius (Gelawdewos) killing the seba’at; Theodore the Oriental (Banadlewos); and George as King of Martyrs. Mural from the north wall of the church of Debre Berhan Selassie at Gondar, likely dated to the early 19th century.48

Equestrian figures: St Victor riding a light tan horse; St Aboli riding a black horse; St Theodore the Oriental (Masraqawi, aka Banadlewos) riding a brown horse, killing the King of Quz and his people; and St George, riding a white horse. Below the horse is the donor, Arnet-Selassie, together with her family, celebrating the completion of the paintings with the priests of the church. Mural from the north wall of the Narthex of the church of the church of Abreha Atsbeha, Tigray, Ethiopia.49

The most common depictions fall into three broad genres; images of saints holding the reigns of their horses; images of saints spearing the enemy; and images of saints in narrative scenes. The choice of the dress and ornamentation of the horsemen, their weapons, the toe or foot inserted into the stirrup, the colorful saddle cloth, and rich horse trappings, typically mirror the way of life of an Ethiopian nobleman in a given period.50

St Mercurius on a black horse defeating Julian the Apostate, in front of him are the brothers; St Basil and St Gregory. Mural from the church of Agamna Giyorgis (Gojjam), Ethiopia.51 note the distinctive toe stirrup and the round church.

Ethiopian princes often underwent a period of training in the art of warfare and horsemanship, especially during royal hunts, which were a notable feature of courtly life since the late Middle Ages. The chronicle of Yohannes (r. 1667-1682), mentions the existence of a stable (Beta Afras) in which the ruler resided at the time of his coronation and states that he had learned to ride while still little more than a child.52

Horse stables were part of the Ethiopian royal complex since the 16th century and are frequently mentioned in later accounts.53 The palace at Dabra Tabor of Ras Ali Alula contained three recesses for the chief's steeds, transforming the royal residence into a stable for “the grandest personages of Abyssinia,” who “feel extreme pleasure to see near them their animals which they passionately love.” Similarly, at King Sahla Sellase's palace at Angolala, the monarch was often seen in the company of his “favourite war steeds” which had managers in close proximity to the royal couch.54

Horses were also given as tribute, gifts, and tithes to important churches and monasteries such as Abba Garima, and Debre Bizen, which often owned large tracts of land. However, horse-riding in the vicinity of churches and other religious sites was discouraged, and everyone was usually required to dismount when approaching a monastery or in the presence of important priests.55

Horse riding remains an important activity among the diverse Equestrian societies of Ethiopia. Horses are involved in social-cultural events such as weddings and ceremonies, they are used in processions during religious and public festivals, in sporting events, and in horse shows such as the Agaw horse riding festival in Amhara and the gugsi horse festival in the Oromia region.56

Today, Ethiopia is reported to possess 2.1 million horses57; which constitutes more than half of Africa’s horse population, and is the legacy of one of the continent’s most enduring equestrian traditions.

Traditional marriage, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, ca. 1930. Smithsonian National Museum of African Art

‘Race of Abyssinian horsemen’ engraving by Eduardo Ximenes from L'Illustrazione Italiana No 7, February 13, 1887

Horseman at a festival in Sandafa Bakkee. image by VisitOromia. A horseman in a lion-mane cape pounds after a foe in a traditional warrior’s game in the Afar region, ca. 1970, Smithsonian National Museum of African Art.

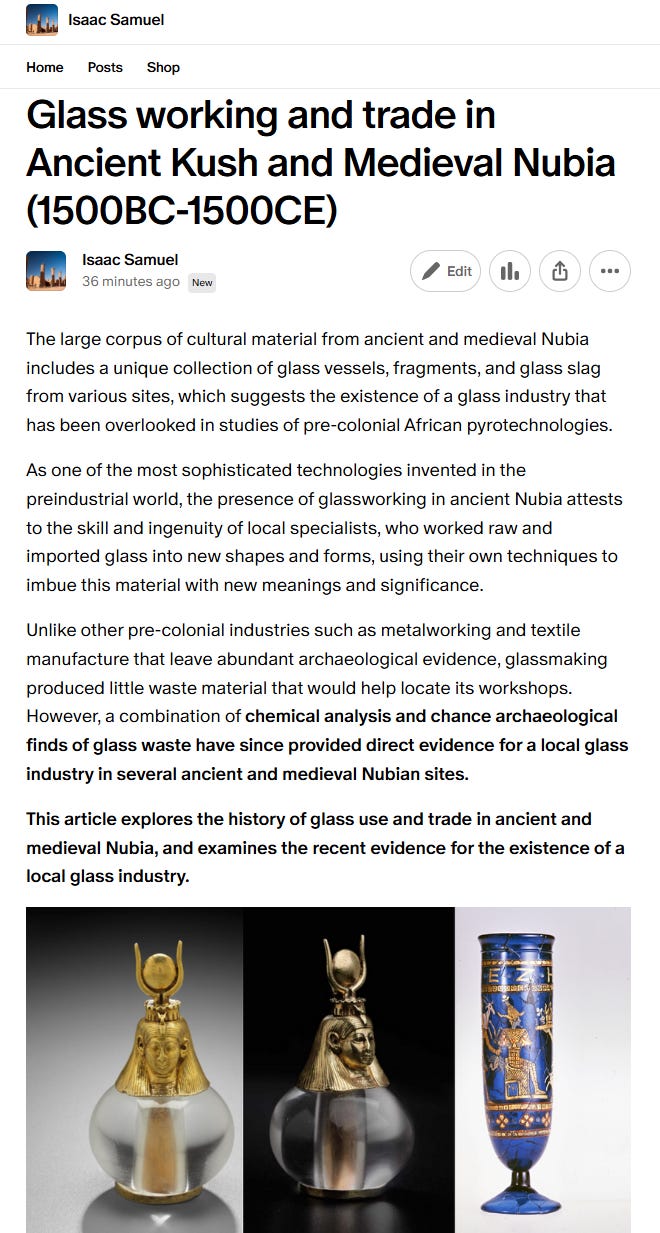

Glass objects were some of the products manufactured by the craftsmen of pre-colonial Africa in the ancient kingdom of Kush and medieval Nubia. The history of glassworking and trade in ancient and medieval Nubia is the subject of my latest Patreon article,

Please subscribe to read more about it here:

Map taken from: The Oromo and the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia: 1300-1700 By Mohammed Hassen pg 335

The Archaeology of Africa: Food, Metals and Towns edited by Bassey Andah, Alex Okpoko, Thurstan Shaw, Paul Sinclair pg 65

Foundations of an African Civilisation: Aksum and the Northern Horn By D. W. Phillipson pg 114

A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly pg 336

Church and State in Ethiopia, 1270-1527 by Taddesse Tamrat pg 114, n.3

A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly pg 344-345

Church and State in Ethiopia, 1270-1527 by Taddesse Tamrat pg 240-241

A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly pg 70-71, Church and State in Ethiopia, 1270-1527 by Taddesse Tamrat pg 375

Medieval Ethiopian Kingship, Craft, and Diplomacy with Latin Europe By Verena Krebs pg 64

Economic History of Ethiopia, 1800-1935 by Richard Pankhurst pg 159

Economic History of Ethiopia, 1800-1935 by Richard Pankhurst pg 161-163

The Oromo and the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia: 1300-1700 By Mohammed Hassen pg 173, A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly pg 476, n. 81

The Oromo and the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia: 1300-1700 By Mohammed Hassen pg 173-174

The Oromo and the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia: 1300-1700 By Mohammed Hassen pg 173-174, 203

Church and State in Ethiopia, 1270-1527 by Taddesse Tamrat pg 167

Economic History of Ethiopia, 1800-1935 by Richard Pankhurst pg 347, 348

Economic History of Ethiopia, 1800-1935 by Richard Pankhurst pg 350, 358

A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly pg 422

Economic History of Ethiopia, 1800-1935 by Richard Pankhurst pg 182-187

Narrative of the Portuguese Embassy to Abyssinia During the Years 1520-1527 by Francisco Alvarez, eds Henry E. Stanley of Alderley, pg 412

Economic History of Ethiopia, 1800-1935 by Richard Pankhurst pg 218-219, 352-354, on the identification of Dequin, see; The Fung Kingdom of Sennar: With a Geographical Account of the Middle Nile Region by Osbert Guy Stanhope Crawford pg 114-115, “The horse was then lean, as he stood about sixteen and a half hands high, of the breed of Dongola.” : Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile by James Bruce

Pedro Páez's History of Ethiopia, 1622, Volume 1, eds Isabel Boavida, Hervé Pennec, Manuel João Ramo, pg 227, 254, 189

Ethiopia's Economic and Cultural Ties with the Sudan from the Middle Ages to the Mid-nineteenth Century by Richard Pankhurst pg 85

The Royal Chronicle of Abyssinia, 1769-1840 by Herbert Weld Blundell pg 382, 386, The Trade of Northern Ethiopia in the Nineteenth and early Twentieth Centuries by Richard Pankhurst pg 55, 66)

The Trade of Northern Ethiopia in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries by Richard Pankhurst pg 70-71, The Royal Chronicle of Abyssinia, 1769-1840 by Herbert Weld Blundell pg 262

The Trade of Northern Ethiopia in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries by Richard Pankhurst pg 72, 80

The Oromo and the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia: 1300-1700 By Mohammed Hassen pg 343, A short history of Awi Agew horse culture, Northwestern Ethiopia by Alemu Alene Kebede pg 5

Morphological diversities and ecozones of Ethiopian horse populations by E. Kefena et al., Phenotypic characterization of Gesha horses in southwestern Ethiopia by Amine Mustefa et al., Kundudo feral horse: Trends, status and threats and implication for conservation by Abdurazak Sufiyan

A Social History of Ethiopia: The Northern and Central Highlands from Early Medieval Times to the Rise of Emperor Téwodros II by Richard Pankhurst pg 156-157, The Royal Chronicle of Abyssinia, 1769-1840 by Herbert Weld Blundell pg 239, 319, 325, 427

The Oromo and the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia: 1300-1700 By Mohammed Hassen pg 173, 195-196

The Oromo and the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia: 1300-1700 By Mohammed Hassen pg 278-343, Islam in Nineteenth-Century Wallo, Ethiopia: Revival, Reform and Reaction By Hussein Ahmed pg 110-120, 164

A Short History of Awi Agew Horse Culture, Northwestern Ethiopia by Alemu Alene Kebede pg 4-5

Economic History of Ethiopia, 1800-1935 by Richard Pankhurst pg 165

A Social History of Ethiopia: The Northern and Central Highlands from Early Medieval Times to the Rise of Emperor Téwodros II by Richard Pankhurst pg 82

Hidden Treasures of Ethiopia: A Guide to the Remote Churches of an Ancient Land by María-José Friedlander, Bob Friedlander pg 29

Church and State in Ethiopia, 1270-1527 by Taddesse Tamrat pg 199-200

A Social History of Ethiopia: The Northern and Central Highlands from Early Medieval Times to the Rise of Emperor Téwodros II by Richard Pankhurst pg 62, 232, 239

A Social History of Ethiopia: The Northern and Central Highlands from Early Medieval Times to the Rise of Emperor Téwodros II by Richard Pankhurst pg 83,

Ethiopian Warriorhood: Defence, Land, and Society 1800-1941 By Tsehai Berhane-Selassie 155

A Social History of Ethiopia: The Northern and Central Highlands from Early Medieval Times to the Rise of Emperor Téwodros II by Richard Pankhurst pg 152

First Footsteps in East Africa: Or, An Explanation of Harar By Sir Richard Francis Burton pg 220-221, 336-337

For God, Emperor, and Country!' The Evolution of Ethiopia's Nineteenth-Century Army by John Dunn 289-299

Hidden Treasures of Ethiopia: A Guide to the Remote Churches of an Ancient Land by María-José Friedlander, Bob Friedlander pg 159-160

The Early History of Ethiopian Horse-Names by Richard Pankhurst pg 198-199

The Early History of Ethiopian Horse-Names by Richard Pankhurst pg 200-205

A Note on the Customs in 15th and Early 16th-century Paintings: Portraits of the Nobles and Their Relation to the Images of Saints on Horseback by Stanislaw Chojnacki in ‘Ethiopian Studies Dedicated to Wolf Leslau’

Hidden Treasures of Ethiopia: A Guide to the Remote Churches of an Ancient Land by María-José Friedlander, Bob Friedlander pg 26-34

Hidden Treasures of Ethiopia: A Guide to the Remote Churches of an Ancient Land by María-José Friedlander, Bob Friedlander pg 185

Hidden Treasures of Ethiopia: A Guide to the Remote Churches of an Ancient Land by María-José Friedlander, Bob Friedlander pg 143-144

Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, Vol. 2: D-Ha 2, A Note on the Customs in 15th and Early 16th-century Paintings: Portraits of the Nobles and Their Relation to the Images of Saints on Horseback by Stanislaw Chojnacki

Hidden Treasures of Ethiopia: A Guide to the Remote Churches of an Ancient Land by María-José Friedlander, Bob Friedlander pg 33

Church and State in Ethiopia, 1270-1527 by Taddesse Tamrat pg 544, The Early History of Ethiopian Horse-Names by Richard Pankhurst pg 198

Pedro Páez's History of Ethiopia, 1622, Volume 1, eds Isabel Boavida, Hervé Pennec, Manuel João Ramo, pg 48, 101,104

The History of Däbrä Tabor (Ethiopia) by Richard Pankhurst pg 237, 240, The Early History of Ethiopian Horse-Names by Richard Pankhurst pg 199-200

A Social History of Ethiopia: The Northern and Central Highlands from Early Medieval Times to the Rise of Emperor Téwodros II by Richard Pankhurst pg 33, 37, 183, Economic History of Ethiopia, 1800-1935 by Richard Pankhurst pg 195-196

A Social History of Ethiopia: The Northern and Central Highlands from Early Medieval Times to the Rise of Emperor Téwodros II by Richard Pankhurst pg 46, Morphological diversities and ecozones of Ethiopian horse populations by E. Kefena et al., Phenotypic characterization of Gesha horses in southwestern Ethiopia by Amine Mustefa et al. pg 9, A short history of Awi Agew horse culture, Northwestern Ethiopia by Alemu Alene Kebede pg 8-14

Phenotypic characterization of Gesha horses in southwestern Ethiopia by Amine Mustefa pg 36, Kundudo feral horse: Trends, status and threats and implication for conservation by Abdurazak Sufiyan pg 9

Good article, however, there is scant evidence of Horses existing during the Aksumite Empire. For example, in the Arabic version of the Martyrdom of Arethas (Alessandro Gori: Tradizioni orientali del «Martirio di Areta», pg 33), it mentions that Emperor Kaleb had "Armed Horses", which were stationed in Himyar after his conquest.

"...Allasbās, king of Abyssinia, after defeating the accursed one, returned to the land of his kingdom. He placed armed horses and a commander among them in the land of Saba."

A very thorough overview of the history of the horse in Ethiopia!

I wrote a short memoir, A Gallop in Ethiopia, centred mostly on the contemporary but also touching on the history of equines in the country. One remarkable feature in Ethiopia was the importance of mules as well.

Yves-Marie Stranger