The Knights of ancient Nubia: horsemen and charioteers from the kingdom of Kush (ca. 1600BC-400CE)

Among the groups of foreigners present in the Assyrian capital of Nimrud in 732 BC, was a community of horse experts from the kingdom of Kush led by an official who supplied horses to the armies of Tiglath-Pileser III.

These African expatriates, who were arguably the first diasporic community from beyond Egypt to travel outside their continent, underscore the importance of equestrianism in the history of the ancient kingdom of Kush.

Kushite charioteers and horsemen created one of the ancient world's largest land empires extending from the eastern Mediterranean to the central region of Sudan. The 25th dynasty Kushite Pharaohs cultivated an equestrian tradition that has attracted favourable comparisons with the chivalrous knights of medieval lore.

This article explores the history of the 'Knights' of the kingdom Kush, and the historical significance of horses in the ancient Nile valley.

Map of the Kushite empire during the 8th century BC.

Sudan’s heritage is currently threatened by the ongoing conflict. Please support Sudanese organizations working to alleviate the humanitarian crisis in the country by Donating to the ‘Khartoum Aid Kitchen’ gofundme page.

Historical Background

Horses were introduced into the Nile valley during the Hyksos dynasty of Egypt and were primarily used for pulling chariots. The sites of Tell el-Dab’a and Tell el-Dab’a in lower Egypt, dated between 1750 and 1500 BC, contain the earliest horse burials in the Nile valley.1

During this period, representations of horse-drawn chariots also appeared in lower Nubia, which was then controlled by the Kingdom of Kerma, which was known in Egyptian texts as the land of Kush. The rulers of Kerma were in close contact with the Hyksos against the Thebean kingdom of Egypt in their middle, and official couriers from both kingdoms traveled via the western desert route likely relying on horse-drawn chariots.2

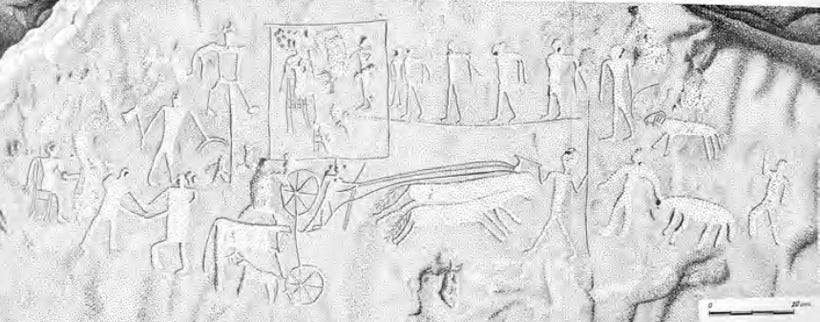

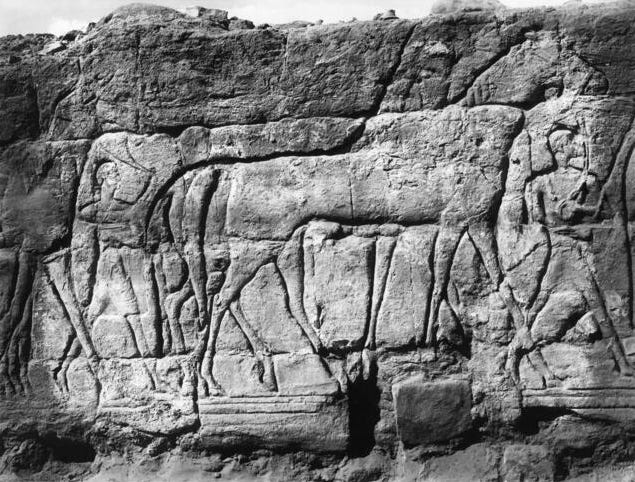

At least one of the several Nubian rock drawings in this region depicts a Kerma victory in the area of Nag Kolorodna in lower Nubia. The drawing, which is dated to the classic Kerma period, shows a male figure on a frame chariot, shown from above with both wheels and axle visible, has one foot on the axle and kneels on the tree between the horses. The Kushite wheeled vehicle is depicted with eight-spoke wheels (unlike earlier Egyptian and Aegean chariots which have four to six) combined with a unique axe held by the charioteer. The image indicates a probable separate development of a heavy chariot in Kush.3

A Kushite victory from Lower Nubia at Nag Kolorodna. image and caption by Bruce Williams.

Four more drawings of chariots from lower Nubia come from the sites of Khor Malik, Kosha, and Geddi-Sabu. These are all simple representations that depict the chariot as viewed from above, two wheels with no spokes or 4 spokes, two animals, and a rider between or in front of them. Unlike the well-executed Nag Kolorodna drawing that can be dated on stylistic grounds given its similarity to Kerma art, these remain undated but were likely also made during the classic Kerma period (ca. 1650-1550BC) when the kingdom expanded into lower Nubia.4

After the fall of Kerma and the Hyksos to New Kingdom Egypt, the chariot continued to be prominently associated with Nubia, with the Egyptian viceroy of Kush often serving as the “driver of the king’s chariot.” Procession and tribute scenes of Nubians delivering tribute to the Egyptians and victory scenes of Egyptian campaigns into Nubia frequently include horses and royal figures riding chariots.5 Horses were also interred with their owners in a few of the elite burials in the New Kingdom period, eg at Sai, Buhen, and Thebes from around the 16th century BC. This was a continuation of a practice that began during the Hyksos era.6

Following the gradual withdraw of the New kingdom from Upper Nubia. Horses continued to feature in the mortuary practices of elite Nubians at the sites of Tombos, Hillat al-Arab, and el-Kurru, pointing to their continued cultural significance.

The exceptionally well-preserved horse burial at Tombos, dated to 1005–893 BC during the early Napatan period of Kush, was found with the remains of an iron bridle and a scarab within a larger pyramid burial. The combination of the burial context and grave goods, including what is arguably the first securely dated examples of iron in Nubia, suggests that horses had acquired symbolic meaning in the early Napatan state whose rulers would later incorporate horse burials into their pyramids at el-Kurru.7

The foundations of Siamun’s pyramid; one of ten in the elite Tombos cemetery.

Tombos horse and Iron cheekpiece. images by Sarah A. Schrader et. al.

The knights of Kush: chivalrous horsemen of the 25th dynasty.

In 727 BC, King Piankhi of Kush conquered an Egypt divided by rival kinglets. He founded the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty, which consolidated a vast territory that extended from the 5th cataract in central Sudan to the eastern shores of the Mediterranean in Palestine. The royal cemetery of the 25th dynasty was at the el-Kurru pyramid complex in Sudan, where Nubian elites had been buried since the 10th century BC, before the burial of Kashta (ca. 760–747 BC), the first known king of what would become the empire of Kush.

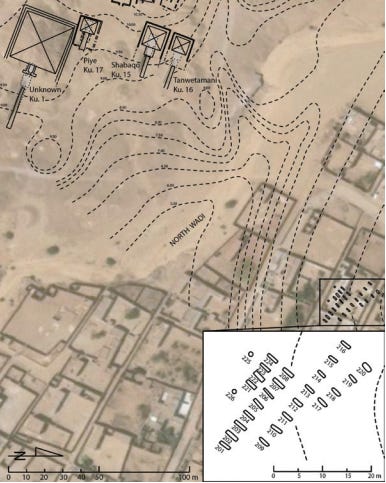

The remains of 24 horses in four graves were found at el-Kurru, with each group consisting of a team for a four-horse chariot. These horses were adorned with decorative and ornate trappings, such as silver plume holders, amulets, and multiple strands of beads. These horses were associated with the four Twenty-Fifth Dynasty Napatan kings: Piankhi (r. 743–712 BC), Shabaka (r. 712–698 BC), Shebitka (r.698–690 BC) and Tanwetamani (r.664–653 BC).8

Pyramids of el-Kurru, Sudan. Flickr image by Ka Wing C.

The northeastern part of the royal cemetery of el-Kurru with a close-up of the horse cemetery. image reproduced by Claudia Näser

Cartouche beads from horse trappings, el-Kurru, Horse grave 211.1919, reign of Shebitka ca. 712–698 B.C. Bead net for a horse, horse grave, Ku 201.1919, reign of Shabaka ca. 698–690 B.C. Plume holder for a horse's bridle, horse grave 219, reign of Piankhy ca. 743–712 B.C. images and captions from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts

According to the archaeologist Sándor Bökönyi, the horses buried at el-Kurru were quite large even by modern standards, with withers heights of 152.29 cm and 155.33 cm (about 15 hands). They were larger than other horses found in the ancient Nile valley, for example, an Egyptian horse from Saqara dated to about 1200BC measured 14 hands. Bökönyi thus argues that the horses of el-Kurru were too large for a light chariot and could be considered riding horses.9

The Historian Laszlo Torok argues that textual and iconographical evidence regarding the use of horses in Kushite warfare shows that the finest horses used in contemporary Egypt and Assyria were bred in, and exported from Nubia. He adds that the development of the large, high-quality horse breed began in Kush before the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty period, and was complimented by the introduction of a heavier chariot carrying three men, and the development of cavalry tactics — which he suggests contributed to Kush’s success in conquering Egypt.10

Piankhi's conquest of Egypt coincided with a shift in ancient warfare to the use of heavy chariots and mounted warrior units, which developed into a powerful weapon of war that was especially utilized by the neo-Assyrian empire as well as the armies of Kush.

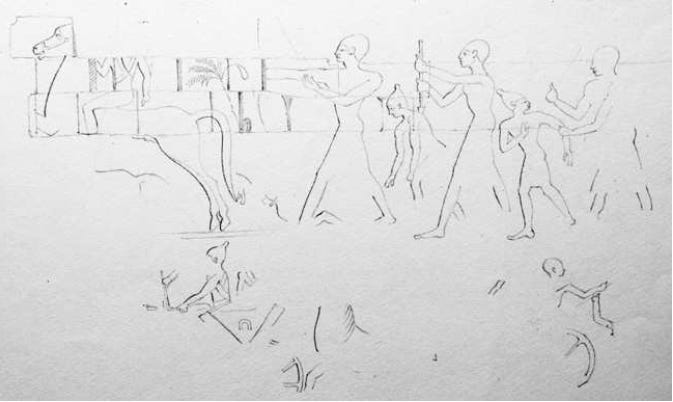

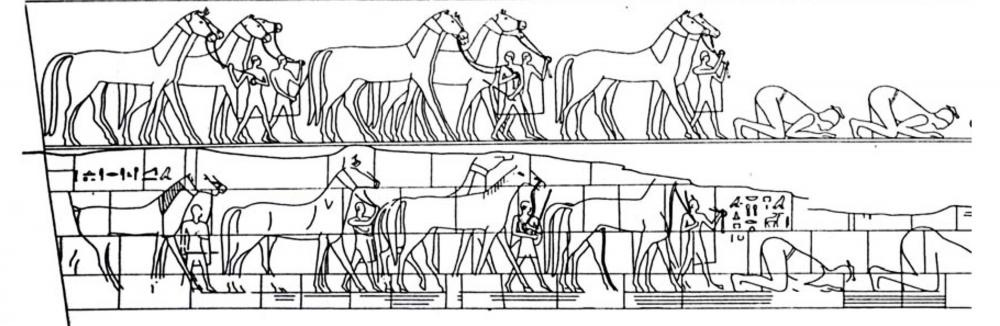

Victory scenes from Piankhi's temple of Amun at Gebel Barkal in Sudan include several depictions of equestrian figures as well as two-man chariots pulled by horses. These scenes include depictions of a warrior wearing a chest band and riding a large horse without a saddle, and two men in chariots who are wearing chest bands. At least one of the charioteers is wearing a helmet, but most are wearing caps, while two of the enemies who are being pierced with arrows are wearing Assyrian-type knobbed helmets.11

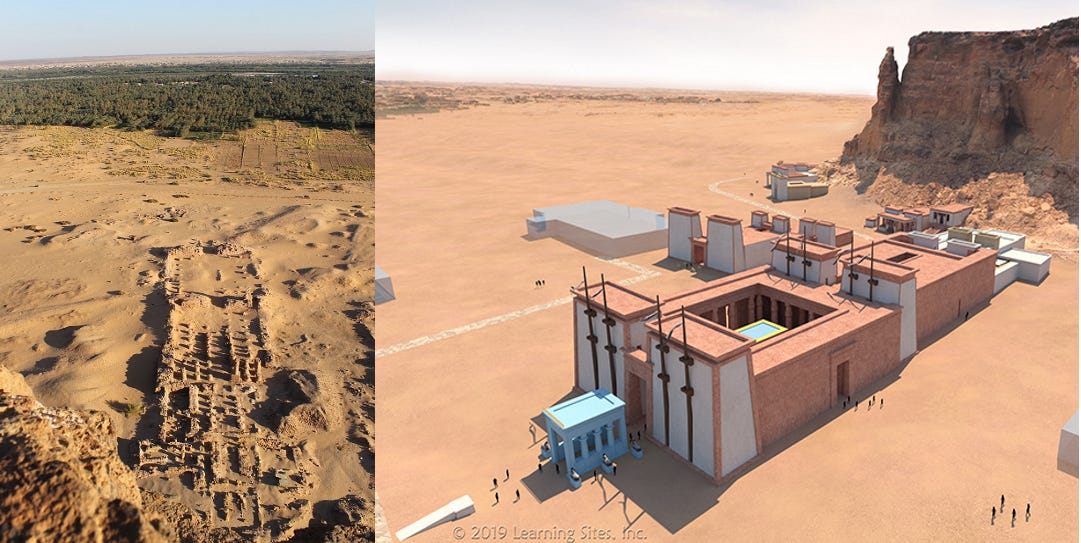

Ruins of the Amun temple at Gebel Barkal, Sudan.

battle scene on the Great Temple of Amun at Gebel Barkal dated to Piankhi’s reign. drawing by W.J.Bankes, ca. 1822.

J. G. Wilkinson’s drawing of the same scene at the Great Temple of Amun at Gebel Barkal. images reproduced by Jeremy Pope

The historian Anthony Spalinger argues that the military scenes and textural evidence reveal an evolution in the art of war in the Nile valley, evidenced by the adoption of the heavy war chariot (of 8 spokes to a wheel), and separate units of cavalry, archery, and chariotry, among other innovations. The absence of heavy armour that was more commonly found among their Assyrian rivals such as helmets and plates, indicates that the armies of the 25th Dynasty were focused principally upon quickly moving units better able to harass and geared to a swift victory rather than to a prolonged battle wherein a large deployment of troops was required.12

Kush's cavalry and chariots mostly fought against foes who shared with them the principles and techniques of a chivalrous, "medieval", warfare, with the accents laid on the validity of the individual warrior in close combat.13

Literary memory of the 25th dynasty period warfare is preserved in the ‘Pedubast Cycle’, a collection of tales that contain “remarkable reminiscences of (roughly Nubian period) historical personages.” They describe exploits of a personal nature, which medievalists would call the heroic deeds of noble knights. And like their chivalrous medieval counterparts, the warriors in the Pedubast cycle rode their horses and chariots to battle but mostly fought while dismounted; their battles were announced beforehand, their arenas were clearly defined, and both sides regarded themselves with respect as equals.14

The link between the 25th dynasty King's love for horses and their chivalry in battle appears in Piankhi’s royal stela in which he admonishes a defeated kinglet for mistreating his horses, as well as in his instructions to his army:

“If he (the enemy) says (to you): ‘Wait for the infantry and the chariotry of another town,’ may you sit (idle) until his army will come. You will fight when he says…

Harness the best horses of your stable, form your battle line, (but) know! Amun is the god who sends us.”15

This link is also evidenced by the stela erected around Year 6 of Taharqo’s reign (ca. 685 BC) on the desert road leading from Memphis that was used for military exercises, which presents a report on the order the ruler gave his army to carry out daily training in long-distance running. According to the inscription, Taharqo followed the race of the soldiers on horseback by running the course of some 50 kilometers in five hours.16

The Assyrians, who shared with the Kushites a love for horses, also wrote about the superiority of the Kushite horse handlers/equestrian experts (musarkisu) and horses (kūsaya) as early as 732 during the reign of Tiglath-pileser III. One of the Neo Assyrian texts mentions a Kushite holding the high military office of “chariot driver of the Prefect of the Land.” Assyrian kings would continue to import large numbers of Kushite horses along with their handlers as late as the reign of Esarhaddon (r. 681 BC-669 BC), even after his armies had prevailed over the Kushite army in Egypt.17

Approximate extent of the Kushite and Assyrian empires. map by Lewis Peake18

[note that since the saddle with the stirrup hadn’t been invented, both Assyrian and Kushite charioteers and horsemen fought primarily with spears and arrows.19]

While the lightly-armoured horsemen of Kush were successful at halting the Assyrian advance outside Jerusalem in their initial encounter around 701BC20, they couldn't withstand the heavy cavalry and siege tactics of the Assyrians whose lengthy invasion of Egypt from 673 to 663 BC ultimately compelled the former to withdraw to Kush. Despite this setback, the prominence of mounted warriors in Kush continued during the late Napatan and Meroitic periods, which were especially important for expanding the kingdom’s sphere of influence.

The stela of King Harsiyotef (ca. 406-369 BC) mentions three campaigns in which he sent his “army and cavalry” against the Metete in Kush's eastern desert region, well beyond the kingdom's heartland in the Nile valley.21 According to his royal chronicle, the Napatan King Nastasen (r. 335-315 BC) “mounted a Great Horse” to take him from his residence in Meroe to the Amun temple at Gebel Barkal for his coronation. This journey was covered in two days through the Bayuda desert, indicating Meroitic control of its western desert region.22

Stele of King Nastasen, ca. 327 BC. Neues Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin Berlin, Germany.

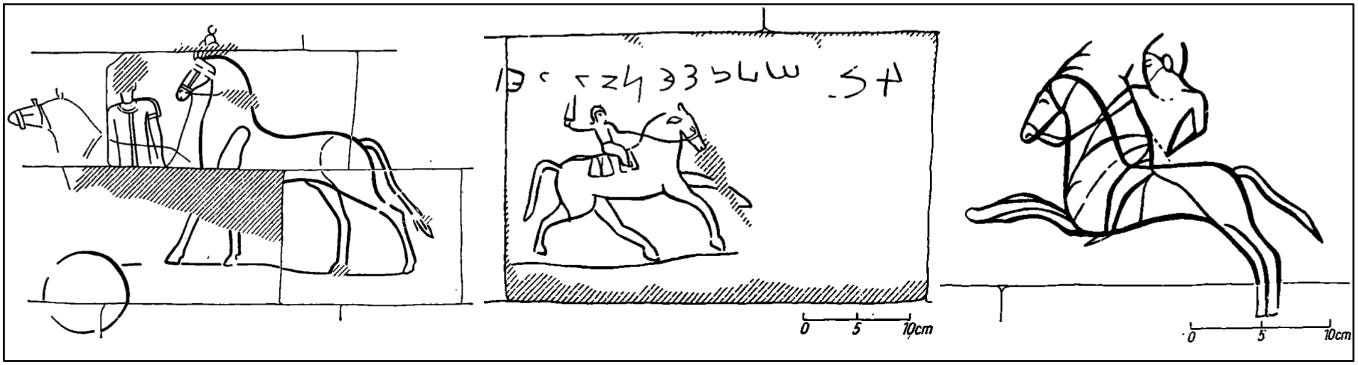

Iconographic evidence of cavalrymen during the Meroitic period comes from Temple 250 at Meroe, which contains various war scenes that include depictions of a harness chariot with 8-spoked wheels, as well as a scene with galloping horsemen and running soldiers. The galloping horses were modeled on Twenty-Fifth Dynasty war scenes: they are messengers bringing the news of a victory, while the soldiers running towards the station chapel and celebrating their victory stand for the returning army.23

Temple 250 was built in the 1st century BC by Prince Akinidad on top of the remains of an earlier building erected by the Napatan King Aspelta. The decoration of its facade had a ‘historically’ formulated triumphal aspect and represents Kush's victory over groups of enemies faced by the Meroitic kingdom. It is also arguably the last depiction of horsemen in battle in the territory of Meroitic Kush, until the inscription of Noubadian King Silko in the 5th century, and its accompanying illustration.24

Temple M250 at Meroe, Sudan. University of Liverpool. ca. 1911.

colourised.

image from Temple M250, Meroe, Sudan, depicting a battle scene showing marching figures and a chariot pulled by a horse. University of Liverpool, ca. 1911.

‘Chariots from Nubia and the Sudan. 3: Meroe, temple of the Sun.’ drawing and caption by L, Allard-Huard.

Colourised

Image from Temple M250, depicting a kiosk with four columns with figures on foot and horses moving towards it. University of Liverpool ca. 1911.

Meroe, Sun temple, Relief on lower podium, Western side. Third quarter of the 1st century BC. drawn by M. Baldi.25

Colourised

The cultural significance of the horse in Kush

As a powerful instrument of warfare on the one hand and a symbol of victory and prestige on the other, horses and their riders feature prominently in the art of Kush.

Horses are a prominent feature of Piankhi’s victory stela, and decorate the walls of his temple at Gebel Barkal; some of the horses are depicted with mounted cavalry, which were only rarely shown in the New Kingdom. At the top of the stela is the submissive king of Hermopolis, Nimlot, who is depicted approaching Piye leading a horse with his left hand and carrying a sistrum in his right hand. In this context, the sistrum was probably destined to calm the fury of His Majesty.26

Relief decorations in the Amun Temple at Jebel Barkal, which depict Piankhi’s military campaign against Egypt, focus on representations of horses, including a scene in which the victorious king receives a tribute of horses, rather than prisoners of the Egyptian iconographic tradition.27

Detail of King Piankhi’s stela at the Cairo Museum, showing Nimlot bringing his horse to the Kushite ruler (center). Image from Alamy.

Close-up of Piankhi’s stela showing the submission of the Egyptian kinglets.

Relief from the Amun temple at Gebel Barkal showing men leading horses to King Piankhy. image from Alamy

Relief decoration in the courtyard of the Amun Temple at Jebel Barkal showing defeated Egyptian rulers in prostrate positions and a procession of horses led towards Piankhi. Image by Tim Kendall

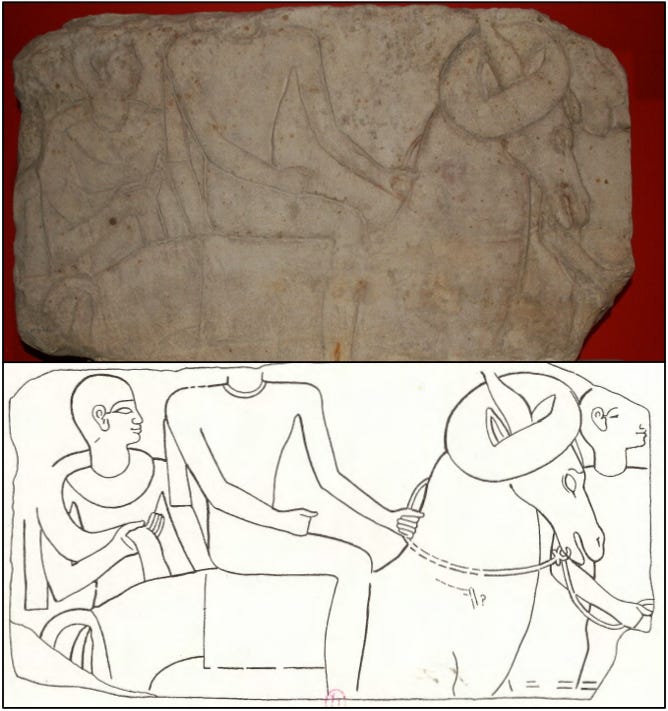

This equestrian iconography of victory can also be seen at the Amun Temple of Taharqo in Sanam and at Kawa, where a relief block depicts a rider on a horse wearing a sun-hat. The excavator of the site of Sanam speculated that a series of rooms comprising the so-called “Treasury” could have been stalls for the stabling of horses.28 Victory scenes from Taharqa's at Sanam and Kawa depict one-man chariots pulled by both horses and mules, and processions of mounted cavalrymen each carrying a short spear and lightly armored. They are seated on cloths displaying rosettes which, seem to support high pommels of saddles in profile.29

Tarhaqa’s temple at Sanam, Sudan.

Sandstone block showing a rider and a horse with a hat. Kawa, Reign of Tahraqa, 7th century BC. Top image from the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, bottom illustration by Macadam 1955, pg Plate Ib.

Top left: ‘Sudanese Nubia. Reliefs from the temple of Sanam. Mounted mules. Top right: ‘Reliefs from the temple of Sanam. Vehicles drawn by mules.’ Bottom: ‘Chariots from Nubia and the Sudan. 1. relief from Sanam.’ images and captions by L. Allard-Huard.30

King Piankhy seems to have had a great admiration for horses. According to the victory stela from Napata when Piankhy entered Hermopolis in triumph and inspected both the palace of Namlot and his stables, where the condition of the horses appalled the king. When he saw that they had suffered hunger, he (Piankhy) said, “...it is more grievous in my heart that my horses have suffered hunger than any evil deed thou has done.”31

Besides this most famous passage, the text of the stela speaks repeatedly about horses: the King mentions the yoking of war horses, “the best of the stable,” in his instructions to his army. Horses are mentioned in connection with the submission of the Egyptian and Libyan kinglets who concluded a peace treaty with the Kushite King. After the ratification of the oath, the chiefs are dismissed in order, as they say, to “open our treasuries, that we may choose as much as thy (i.e. Piankhi’s) heart desires, that we may bring to thee the best of our stables, the first of our horses.”32

The remarkable burials of the royal chariot horses in standing position, occasionally wearing their plumed head decoration, covered with bead nets, and provided with funerary amulets are testimonies to the Kushite love of horses.33

This tradition of rich horse burials continued during the Meroitic and post-Meroitic periods. In Meroitic royal burials, horses also wore bells decorated with images of vanquished enemies. In the post-Meroitic period, the tombs at Ballana, Qustul, and al-Hobaji included the burials of the owners’ horses, complete with trappings and rich grave goods.34

There are a number of artworks dating to the Meroitic period that demonstrate the continued cultural importance of the horse in Kush. These include several locally manufactured horse trappings and plumes, as well as an imported oil lamp with a horse-shaped handle.35 Graffito from the temple of Mussawarat also includes depictions of horses and their riders. Stylistically, the images date to the transition between the Meroitic and post-Meroitic eras between the 3rd to 5th century CE.36

Fragment of a Meroitic-era bowl depicting a horseman, Liverpool World Museum. Image by L. Torok.

Bronze plume holder in the form of papyrus flower surmounted by a falcon wearing the double crown, Pyramid Beg. W. 24, Meroe. Silver horse trappings in the form of a lion's head representing Apedemak, Pyramid Beg. N. 16, Meroe. Silver horse trappings in the form of a charging lion, reign of Aryesbokhe, ca. 215–225. All images from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Lamp with a handle in the form of a horse, Pyramid N 18, Meroe. 1st century CE. Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Temple of Musawwarat es-Sufra, Sudan.

Graffiti depicting a lone horse at the temple of Musawwarat, the horse is wearing a halter and is sadled. Image by Cornelia Kleinitz. Man Riding Horse and rider at the temple of Musawwarat. image by Eric Lafforgue

Horses and Horsemen at Mussawarat, Images by Ursula Hintze

A 4th-century Roman account describing the arrival of envoys from Kush, alongside the Blemmyes and the Aksumites, mentions horses among the list of gifts brought to the emperor Constantine (r. 306-337). These envoys also brought with them “shields and long spears and arrows and bows, indicating thereby that they offered their service and alliance to the Emperor if he saw fit.”37

In the middle of the 4th century, the region of lower Nubia, whose control had been divided between Meroitic Kush and the Blemmyan chiefdom, gradually passed into the hands of the Noubadian rulers after Aksum’s invasion of Meroe.38 Some of the horsemen of Nubia eventually allied with the Eastern Roman Empire. The 5th-century illustration of the Noubadian King Silko depicts him wearing a Roman military garb consisting of a short mail tunic and a cape, while riding a caparisoned horse.39

5th-century inscription of King Silko and his depiction on the Mandulis temple at Kalabsha.

The centrality of horses in the middle Nile valley region would continue long after the fall of ancient Kush, with the rise of the medieval Christian Nubia and the Muslim sultanate of Darfur. The region would become one of the main horse-breeding centers in Africa, supplying the cavalries of West Africa and northeast Africa for the rest of the pre-colonial period, creating one of the longest-enduring equestrian cultures on the continent.

Nubian Horseman at the Gallop, Alfred Dedreux (d. 1860)

African history is awash with stories of powerful women like Queen Amanirenas of Kush, who is briefly referenced in the New Testament book of Acts which mentions the eunuch of the ‘Candance’ traveling in a chariot to meet Philip the evangelist.

My latest Patreon article chronicles the history of another equally famous African Queen; Eleni of Ethiopia, from her obscure origins as a Muslim princess to her rise as one of Africa's most powerful women.

Please subscribe to read about it here:

Of Kings and Horses: Two New Horse Skeletons from the Royal Cemetery at el-Kurru, Sudan by Claudia Näser and Giulia Mazzetti pg 124

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia edited by Geoff Emberling, Bruce Williams pg 186

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia edited by Geoff Emberling, Bruce Williams pg 191, 196 n.41)

Nile-Sahara: Dialogue of the Rocks. III. Innovative Peoples: The Horse, Iron and the Camel by Allard-Huard, L. pg 29-32)

Between Two Worlds: The Frontier Region Between Ancient Nubia and Egypt By László Török pg 173-179, The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia edited by Geoff Emberling, Bruce Williams pg 333, 378, Nile-Sahara: Dialogue of the Rocks. III. Innovative Peoples: The Horse, Iron and the Camel by Allard-Huard, L. pg 25-26,

Of Kings and Horses: Two New Horse Skeletons from the Royal Cemetery at el-Kurru, Sudan by Claudia Näser and Giulia Mazzetti pg 124, Symbolic equids and Kushite state formation: a horse burial at Tombos by Sarah A. Schrader pg 386, 388)

Symbolic equids and Kushite state formation: a horse burial at Tombos by Sarah A. Schrader pg 386-395

Symbolic equids and Kushite state formation: a horse burial at Tombos by Sarah A. Schrader pg 387

Of Kings and Horses: Two New Horse Skeletons from the Royal Cemetery at el-Kurru, Sudan by Claudia Näser and Giulia Mazzetti pg 128, on the size of New Kingdom Egyptian horses, see: Nile-Sahara: Dialogue of the Rocks. III. Innovative Peoples: The Horse, Iron and the Camel by Allard-Huard, L. pg 13

The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization By László Török pg 158

Notes on the Military in Egypt during the XXVth Dynasty by A.J. Spalinger pg 46-52,

Notes on the Military in Egypt during the XXVth Dynasty by A.J. Spalinger pg 53-57

The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization By László Török pg 158-159)

Notes on the Military in Egypt during the XXVth Dynasty by A.J. Spalinger pg 58, Beyond the Broken Reed: Kushite intervention and the limits of l'histoire événementielle by J. Pope pg 113 Legends of Iny and “les brumes d’une chronologie qu’il est prudent de savoir flottante” by Jeremy Goldberg pg 6,

“The word chivalry is cognate with the French words cheval (horse) and chevalier (horseman), and while a horse elevated a warrior socially as well as physically, actual fighting by Knights in this period was often conducted on foot… On battlefields of the twelfth century, decisive mass cavalry charges were unusual, and in set-peice battles of the period Knights habitually fought dismounted.” Medieval Warhorse: Equestrian Landscapes, Material Culture and Zooarchaeology in Britain, AD 800–1550 By Oliver H. Creighton, Pg 25-27

“It is therefore not surprising to find that the full-scale cavalry charge was not used as extensively as might be expected.” Armies and Warfare in the Middle Ages: The English Experience by Michael Prestwich pg 311-326

Piankhy’s Instructions to his Army in Kush and their Execution by Dan’el Kahn Pg 125-126)

Daily Life of the Nubians by Robert Steven Bianchi pg 168, The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization By László Török pg 173-174)

The Horses of Kush by Lisa A. Heidorn pg 107-110, Beyond the Broken Reed: Kushite Intervention and the Limits of l’histoire événementielle by Jeremy Pope pg 155-156)

The invisible superpower. Review of the geopolitical status of Kushite (Twenty-fifth Dynasty) Egypt at the height of its power and a historiographic analysis of the regime’s legacy by Lewis Peake pg 451

The Rescue of Jerusalem: The Alliance Between Hebrews and Africans in 701 BC by Henry T. Aubin pg 53, Notes on the Military in Egypt during the XXVth Dynasty by A.J. Spalinger pg 49

The Rescue of Jerusalem: The Alliance Between Hebrews and Africans in 701 BC by Henry T. Aubin, Jerusalem's Survival, Sennacherib's Departure, and the Kushite Role in 701 BCE: An Examination of Henry Aubin's Rescue of Jerusalem by Alice Bellis

Fontes Historiae Nubiorum: From the mid-fifth to the first century BC by Tormod Eide pg 449, 451, 602, Aksum and Nubia: Warfare, Commerce, and Political Fictions in Ancient Northeast Africa by George Hatke pg 81-82

From Food to Furniture: animals in Ancient Nubia by Salima Ikram pg 214, Enemy brothers. Kinship and relationship between Meroites and Nubians (Noba)" by Claude Rilly pg 215

Nile-Sahara: Dialogue of the Rocks. III. Innovative Peoples: The Horse, Iron and the Camel by Allard-Huard, L. pg 29, The Image of the Ordered World in Ancient Nubian Art By László Török pg 221, 233

The Image of the Ordered World in Ancient Nubian Art By László Török pg 212-215, 222

The king Amanikhareqerem and the Meroitic world: an account after the last discoveries by M. Baldi, pg 159

Symbolic equids and Kushite state formation: a horse burial at Tombos by Sarah A. Schrader pg 387, Meroe: Six Studies on the Cultural Identity of an Ancient African State by László Török pg 196

Of Kings and Horses: Two New Horse Skeletons from the Royal Cemetery at el-Kurru, Sudan by Claudia Näser and Giulia Mazzetti pg 130

The Horses of Kush by Lisa A. Heidorn pg 106

Nile-Sahara: Dialogue of the Rocks. III. Innovative Peoples: The Horse, Iron and the Camel by Allard-Huard, L. pg 21, 28-29.

Nile-Sahara: Dialogue of the Rocks. III. Innovative Peoples: The Horse, Iron and the Camel by Allard-Huard, L. pg 20, 28, 29.

Daily Life of the Nubians by Robert Steven Bianchi pg 160

Meroe: Six Studies on the Cultural Identity of an Ancient African State by László Török pg 195-196)

The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization By László Török pg 158)

From Food to Furniture: animals in Ancient Nubia by Salima Ikram pg 215, The Nubian Past: An Archaeology of the Sudan by David N. Edwards pg 191, 194, 207)

The Origins of Three Meroitic Bronze Oil Lamps in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston by Stephanie Joan Sakoutis pg 66, 69

Proceedings of the 14th International Conference for Nubian Studies, edited by Marie Millet, Frederic Payraudeau, Vincent Rondot, Pierre Tallet pg 986-987, Africa in Antiquity. The Arts of Ancient Nubia and the Sudan Proceedings of the Symposium Held in Conjunction with the Exhibition, Brooklyn, September 29 – October 1, 1978, Illustrated by Fritz Hintze pg 140-143

Fontes Historiae Nubiorum. Textual Sources for the History of the Middle Nile Region Between the Eighth Century BC and the Sixth Century AD Vol III pg 1081

Aksum and Nubia: Warfare, Commerce, and Political Fictions in Ancient Northeast Africa by George Hatke

Africa in Antiquity: The Arts of Ancient Nubia and the Sudan Vol. I by Steffen Wenig pg 117

Have been working through the past few articles this week and really enjoying all of the fantastic work you put out. Thank you Isaac for the always insightful and fascinating pieces of history that should be better known!