The ruined stone towns of medieval Somaliland and the empire of Adal (ca. 1415–1577)

At the end of the Middle Ages, a flourishing network of urban sites and stone settlements was integrated into the empire of Adal which covered large parts of western and central Somaliland.

Historical accounts of the Adal period, which describe the empire’s entanglement in the Portuguese-Ottoman wars of the 16th century in great detail, say little about the stone towns of Somaliland, whose ‘mysterious’ ruins first appear in the documentary record in the mid-19th century.

Recent archeological research across dozens of ruined towns has established that most were founded during the Adal period before they were gradually abandoned and transformed into pilgrimage sites.

This article explores the history of the ruined towns of Somaliland and their significance in the historiography of the medieval empires of the region.

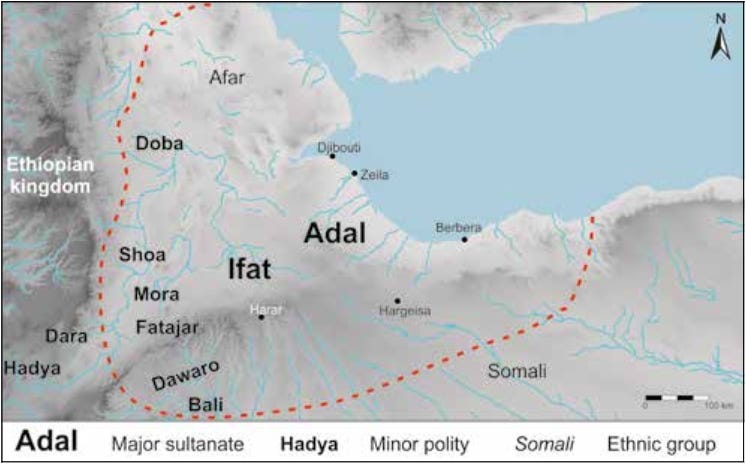

Map showing the medieval ruined towns of the northern Horn of Africa.1

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more on African history and keep this blog free for all:

A description of the stone towns of Somaliland.

Until recently, the history of the medieval sultanate of Adal has been reconstructed using a significant corpus of written sources, which are mostly concerned with the western half of the state in what is today Ethiopia.

Over the last two decades, new archaeological discoveries in Somaliland have uncovered the ruins of over 30 sites whose material remains shed more light on the eastern half of the Sultanate. Most ruined settlements share a remarkable spatial and architectural uniformity, regardless of their location or size, which points to a basic common identity shared by the medieval Muslim states of the Horn of Africa.

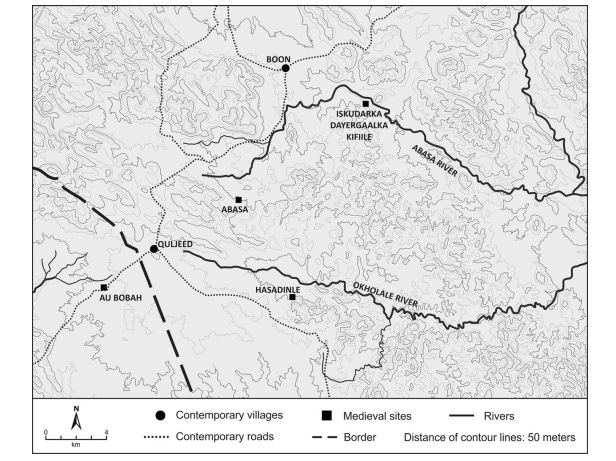

There are several clusters of ruined sites in the western and central regions of Somaliland, with a few isolated ruins in the east.2

Medieval sites of Somaliland. Map by Jorge de Torres Rodríguez

The largest among the western ruins is the 56ha site of Abasa, near the modern city of Boorama, close to the border with Ethiopia. It consists of the ruins of about 200 stone houses each measuring 20-40 m2, a large mosque measuring 18x17m and a small secondary mosque, two graveyards, and a palatial building measuring 31×8m with wide walls and a monumental entrance that could be interpreted as a stronghold. The vast majority of the site's material culture consisted of local pottery, with only a few imported wares from China and Yemen dating to the 15th and 16th centuries.3

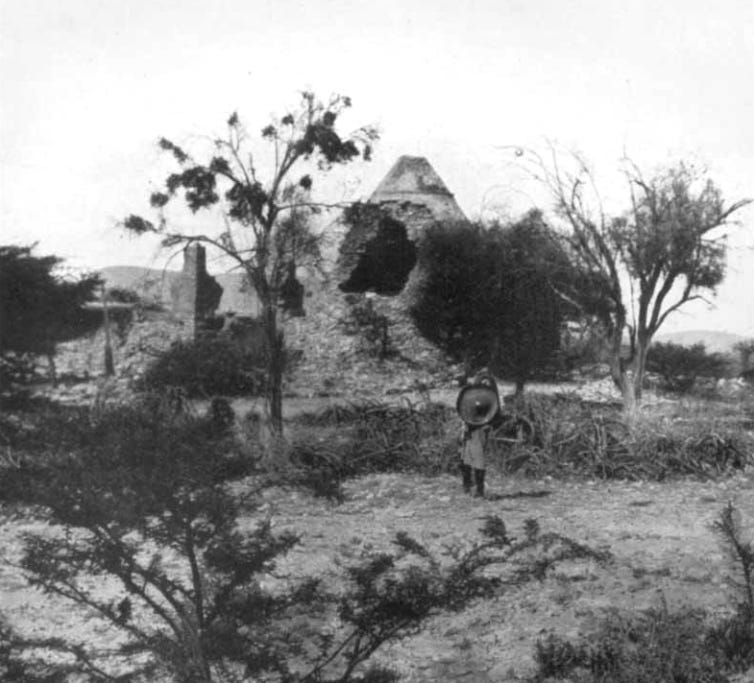

The mosque at Abasa looking towards the Mihrab, image by R.H.Taylor, reproduced by A.T.Curle, ca. 1934-1937

"Abassa. View of "temple" from East End." ca. 1880-1950, Somaliland. British Museum Af,B53.17

‘Abassa. Part of S. wall of "Temple" ca. 1880-1950. Somaliland. British Museum.

current state of the mosque at Abasa. image by Jorge de Torres Rodríguez

Monumental entrance to the monumental building at Abasa, image by Jorge de Torres Rodríguez

There are several sites within the vicinity of Abasa such as Hasandile, an 11ha site consisting of a mosque and about 60 stone houses, the largest of which measures 14x9m. The site lacks any imported wares. agricultural vocation of the site is supported by the wide alluvial plain in front of the houses, where cultivated parcels are still visible, and by the number of querns found throughout the site. The material culture collected in Hasadinle is almost completely of local origin and very similar to that found at Aabsa, with only a few imported wares that were originally made in northern Ethiopia.4

Not far from Abasa is the archaeological site of Amud, whose ruins extend over an area of about 10ha. The structures include over 200 houses, all well-built of stone, with interior niches in the walls and rectangular windows with stone lintels. The mosque is found in the southern half of the town, which is also constructed with dry stone and features pillars that support the flat roof. The graves of Amud resemble those found at Abasa, and so too does that material culture which consists of mostly local pottery and a few imported wares similar to those found at Amud.5

The ruined town of Amud. image by A.T.Curle, ca. 1934-1937

“Amud. Principal building, looking towards Buramo” ca. 1880-1950, Somaliland. British Museum Af,B53.19.

(left) “Amud. Principal building. Inside view of a room.” ca. 1880-1950, Somaliland. British Museum Af,B53.16 (right) Triangular headed niches in the wall of a house at Amud. image by R.H.Taylor, reproduced by A.T.Curle, ca. 1934-1937

The ruins found in the central region south of the coastal city of Berbera include the caravan station and fort of Qalcadda, whose ruins include a rectangular enclosure (55×90 m) with thick walls of dressed stone and corners defended by round bastions. To the south of this fort is a square building with an inner courtyard resembling a caravanserai. Neighbouring sites include the 6ha site of Bagan whose ruins consist of about 85 stone houses; and Gidheys, a 2ha site located on the route to Fardowsa, which features remains of stone buildings and graves.6

The caravan station of Qalcadda. 1 Satellite image of the site (Google Earth), 2 Detail of the several plaster floors of the excavated area, 3 Plan of the east nave and the test pit, 4 Test pit, 5 Comparison between Qalcadda and a Persian caravanserai. images and captions by Jorge de Torres Rodríguez

"Eik. 40 miles S. of Burao. General view of ruins" ca. 1880-1950, Somaliland. British Museum Af,B53.23.

Excavations at the site of Fardowsa uncovered several rectangular stone buildings, the largest of which measured 14mx7.4m, surrounded by a fence, open spaces, and graves. The material culture of the site included local pottery and metal, imported wares from China and Yemen, as well as glass vessels, and cowries. Radiocarbon samples collected from one of the houses yielded dates between 1327–1351 CE and 1595–1618 CE, which fall within the period of the Sultanate of Adal (1415–1577), with a final, sporadic occupation between 1499–1600 CE.7

The size and spatial organization of Fardowsa, its strategic location along the trade route from the city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia to the coastal city of Berbera, and the relatively large amount of imported pottery found at the site compared to the sites of Amud (10% vs 1%), indicate that it was part of the rich urban network that flourished during the period of Adal.8

Excavation areas at Fardowsa. image by Jorge de Torres Rodríguez et. al.

General view of the site: with C-3000 to the left, C-4000 to the bottom right, and C-6000 (courtyard) to the right front. image and captions by Jorge de Torres Rodríguez et. al.

General view of C-3000. image by Jorge de Torres Rodríguez et. al

The largest of the easternmost ruins is the site of Maduuna near the modern town of el Afwyen. The ruins consist of a large rectilinear mosque without columns that was built with drystone. Its walls were originally rendered with lime plaster and are currently the best preserved among the ruined towns of Somaliland, standing at a height of about 3m. The rest of the ruins include a smaller mosque and several curvilinear structures of drystone masonry. Material culture from the site consists mostly of local pottery and a few imported wares from Aden dated to the 17th century.9

Three other towns have been identified further east of Maduuna in Puntland, showing that inland permanent settlements existed in the easternmost parts of the Horn of Africa during the medieval period. Images and descriptions of these three sites show architectural similarities with the constructions at Maduuna, featuring round houses grouped in clusters, which suggests the influence of nomadic architecture in this region, in contrast to the sites found in the western and central regions.10

Ruined mosque of Maduna, Somaliland. Alamy images.

Miḥrāb and niches of the Maduuna congregational mosque. image by StateHorn

Ruined houses in Maduuna. image by Abdiqaadir Abdilaahi Yusuf

Most of the ruined towns possess a mosque built using the same construction technique as the rest of the buildings with square mihrabs and in some cases perimeter walls surrounding the building. In the bigger mosques such as those in Abasa and Hasadinle, circular or square pillars were used to support a flat roof. Unlike the mosques of Zeila, none found in the interior sites have minarets or minbars, pointing to the development of a unique architectural tradition in the interior.11

Excavations in the coastal region around the port town of Berbera point to an expansion of trade during the 15th-16th century period, from sites like Siyaara and Farhad. Imports from Yemen diminished, while the number of East Asian wares especially from China, grew significantly, which reflects similar changes in the western Indian Ocean. The abundance of imported wares at these coastal sites relative to the interior sites indicates that the Indian Ocean trade went through Somaliland, but the commodities didn't remain in Somaliland.12

In the 1930s, a few coins were recovered from surface finds at the sites of Derbi Adad in the region of Amud and the site of Eik, which is further south of the site of Fardowsa. The coins from Derbi Adad belong to sultan Kait Bey of Egypt (r. 1467-1495), while those from Eik were gold coins issued by sultan Selim II (r. 1566-1574).13 One coin was also recovered from the site of Fardowsa, and dated to between the 13th and 17th centuries.14 The use of imported coins in the Muslim cities of the northern Horn is also mentioned in 15th-century Portuguese accounts regarding the kingdom of Ifat.15

In the interior, only the largest sites, such as Fardowsa, Abasa, and Amud can be considered cities or towns, while the rest are likely to have been hamlets or religious centers. Although it has generally been assumed that these settlements were involved in trade, the low percentages of imported materials and the more abundant evidence for agricultural activity suggest that the economy of many of these settlements was based on agriculture.16

The local pottery of most interior sites shows a high standardization in terms of technique, shapes, and decorations, and was different from those found in contemporaneous sites like Harar and Shewa. This suggests a shared social identity across the sites regardless of the region or the characteristics of the site. At the close of the 16th century, imports suffered a dramatic decline throughout Somaliland, materials from the 17th century are very scarce and concentrated in few places along the coast.17

By this time, many of the interior towns were abandoned and a few were transformed into pilgrimage sites.

The ruined towns of Somaliland and the empire of Adal.

“The scene was still and dreary as the grave; for a mile and a half in length all was ruins—ruins—ruins.”

Richard F. Burton at Abasa in 1854.

The history of the medieval empire of Adal, known in internal sources as the sultanate of Barr Sa'd al-Din, is represented by a complex mosaic of written sources from both internal and external accounts. Much of western and central Somaliland fell under the control of the Walasma sultans of Barr Saʿd al-Dīn, whose forces were progressively involved in a series of conflicts with the Solomonic monarchs of Christian Abyssinia/Ethiopia.

Distribution of the main polities and ethnicities during the Middle Ages in the Horn of Africa. Map by Ulrich Braukämper, reproduced by Jorge de Torres Rodriguez

The northern Horn of Africa during the early 16th century. Map by Matteo Salvadore

The polity of Barr Saʿd al-Dīn (“Land of Saʿd al-Dīn”) was ruled by the Walasma dynasty that had been displaced from Ifat by the Christian Ethiopian kingdom in the early 15th century. Following its re-establishment, the new state grew rapidly and expanded towards the east, while conducting an aggressive policy against the Ethiopian kingdom to its west, which culminated in the invasion of the latter by the forces of Barr Saʿd al-Dīn under Imām Aḥmad Gragn in the 1520s.

The empire established by Imām Aḥmad lasted until his death in battle with the Ethiopian forces in 1543, after which it was reduced to a rump state on the outskirts of Harar by the close of the century.

Archaeologists suggest that the western ruins of Abasa and Amud were likely included in the territory directly controlled by the sultanate of Adal despite their absence in contemporary accounts. In central Somaliland, the presence of a caravan station and a major trade hub at Fardowsa points to the influence, but not control, of the state of Adal. Farther to the east, the region around Maduuna lay in nomadic territory, with minimal influence of the Adal sultans. Prostelyzation in the easternmost sites was likely directed by scholars/holymen who are frequently mentioned in the traditional histories of the region.18

Regardless of their function, location, and size, all the known inland settlements disappeared by the end of the 16th century during the political upheavals of the period, which coincided with the arrival of the Portuguese and Ottomans in the western Indian Ocean, who profoundly altered pre-existing patterns of exchanges and conflict.

The Portuguese raided the coast of Yemen and the Hejaz, and later attacked the port cities of Zeila in 1517 and Berbera in 1518. The disturbance caused by the Portuguese military campaigns on the Red Sea shores affected one of the main economic activities in central Somaliland. The concurrent expansion of the armies of the Adal sultanate into the Ethiopian highlands and their later defeat marked a period of social upheaval that ended with the expansion of Oromo-speaking herders from the south.19

None of the ruined settlements of Somaliland were walled, except the fortress and caravanserai at Qalcadda. This lack of defenses is surprising considering the permanent state of war between the empires of Adal and Ethiopia described in the written sources, and is perhaps explained by the more distant position of the Somaliland sites from the border with the Christian kingdom. Fortresses and fortified settlements are more common in sites such as Harar, which are closer to the Ethiopian highlands.20

Additionally, none of the ruined sites have shown evidence of destruction, and the good state of preservation of many of the buildings even in the early 20th century points to a peaceful, progressive abandonment once the political and economic structures that sustained them disappeared. At that time, the nomadic lifestyle likely proved far more efficient than ever-hazardous agriculture in a semidesert region such as Somaliland.21

Traditions collected in the 19th and early 20th centuries often associate the ruined sites with Muslim saints who battled with and later displaced the pre-Islamic rulers. They also indicate that the sites were gradually transformed into places of pilgrimage by local visitors long after the collapse of the Adal sultanate.

The 19th-century British traveler Richard Burton visited the site of Abasa and passed by the site of Amud in December 1854. He described the ruins of Abasa in detail as well as a local tradition from his Somali informants, who mention that the town was ruled by an Oromo queen known as Darbiyah Kola.22

For Amud, he referred to the visitation places of three celebrated saints, Amud, Sau, and Sharlagamadi in the neighborhood. Later travelers recounted that a number of ruined settlements in the region were also named after a local saint or holy man, prefixed by Au or Aw (meaning “holy men,” in Somali). It occurs in two cases where there are ruins, at Au Bare and Au Buba/ Aw Boba, the latter of which is on the Ethiopian side of the border. A son of a Sheik Boba is mentioned as being one of the Muslim commanders with Somalis under him in the Adal invasion of 1529.23

Location of the site of Aw Boba/ Au Buba in relation to Abasa. Map by Jorge de Torres Rodríguez

The tomb of sheikh Au Boba. image by A.T.Curle, ca. 1934-1937

Burton relates a story in which the town of Saint Aw Boba was the bitterest enemy of Queen Kola who ruled the town of Abasa. The saint was reportedly a revered holy man whose descendants fought alongside Imam Ahmad Gragn in the first half of the 16th century, thus directly linking the town’s history to the Adal sultanate period.

"It is said that this city [Abasa] and its neighbor Aububah fought like certain cats in Kilkenny till both were ‘eaten up:’ the Gudabirsi fixed the event at the period when their forefathers still inhabited Bulhar on the coast,—about 300 years ago. [ie 1550 CE]"24

One such ruined settlement associated with religious figures is the site of Dameraqad, just north of Amud, which consists of about 15 stone structures linked together by walls defining courtyards. At least three of the buildings are squared mosques, the bigger one with two pillars and three rooms attached occupied by well-built tombs. The site is dated to the end of the Middle Ages and was in continued use long after the fall of Adal, thus resembling other sites associated with holy men such as Aw Bare, Aw Boba, and Aw Barkhadle.25

Ruined Mosques in Dameraqad. image by Jorge de Torres Rodríguez

The site of Aw-Barkhadle is an important pilgrimage center that includes several archaeological remains and a mausoleum of Saint Aw-Barkhadle (a.k.a Sharif Yusuf Al-Kawnayn) who is said to have reached the region about 850 years ago.

The site appears to be of significant antiquity, with evidence of pre-Islamic burial mounds and phallic gravestones, as well as Christian and Jewish graves marked with Coptic crosses and a star of David. The ruins of the site cover about 4sqkm, and include the foundations of house structures, a mosque, a town wall about 3km long, and surrounding graves. The mausoleum of the Saint, which was completed in the 19th century, is surrounded by dozens of white-washed tombs belonging to various figures who lived between the 13th century and the 19th century.26

Site plan of Aw-Barkhadle. image by Sada Mire

The Mausoleum of Saint Aw-Barkhadle

(left) A Coptic Christian cross marked gravestone in situ at Aw-Barkhadle. (right) A gravestone marked with the Star of David, found in Dhubato area. images and captions by Sada Mire

According to the archaeologist Sada Mire who has surveyed the site and its related historical documents, the saint Aw-Barkhadle appears in some of the kinglists of the Walasma dynasty of Ifat and Adal. A chronicle from Harar, The Tarikh al-Mujahidin, discusses the death of Garaad Jibril who revolted against the city’s ruler sultan ‘Uthman’ (d.1569) and mentions ‘the place of the great saint known as Aw Barkhadle’, as Jibril’s burial place. A later account by Philipp Paulitschke in 1888, which identifies the capital of Adal as ‘AwBerkele’ indicates that the walled settlement may have functioned as the capital of Ifat and Adal at the end of the Middle Ages.27

Alternatively, the town of ‘Abaxa’ [presumably Abasa] is briefly mentioned in a Portuguese account from 1710 as the “capital city of the kingdom of Adel, adjoyning to Ethiopia, whose emperors were once masters of it”. However, most historians and archeologists suggest that the capital of Adal, which was changed frequently between the 15th and 16th centuries, may have been located in the vicinity of Harar, with the city itself briefly serving as the main political center of the Sultanate.28

Harar, Ethiopia, ca. 1944. Quai Branly.

Conclusion: New perspectives on the empire of Adal.

Despite the silence of historical records regarding the eastern half of the empire of Adal, the archeological evidence from the ruined sites of Somaliland provides evidence for the emergence of trade hubs and nucleated settlements across the region between Harar and the coast which flourished at the height of Adal period.

The general lack of defenses at the sites, their gradual abandonment, and their continued veneration by pilgrims as the homes of important saints suggest a more stable political and economic environment in the eastern regions of Adal, in contrast to the near-constant state of war in the frontier regions bordering the territories of the Solomonids.

The archaeological data presented above shows that while the study of the medieval Muslim states of the Horn of Africa is often framed by their confrontation with the Christian kingdom of Ethiopia, this dichotomy simplifies the complex world of the northern Horn of Africa at the end of the Middle Ages.

Maduna, Somaliland. Alamy images.

The southwestern region of Kenya is dotted with the ruins of over 138 stone-walled sites containing 521 structures, the largest of which is the UNESCO World Heritage site of Thimlich Ohinga whose walls stand at a height of over 4 meters. The historical record of this region describes over 500 walled settlements known as forts, some of which were besieged during the colonial invasion.

The stone ruins of Thimlich Ohinga and the forts of western Kenya are the subject of my latest Patreon article.

Please subscribe to read more about it here:

Map by StateHorn

for a more detailed Map of the historical sites in Somaliland, see: Mapping the Archaeology of Somaliland: Religion, Art, Script, Time, Urbanism, Trade and Empire by Sada Mire

Kola’s Kingdom: The Territory of Abasa (Western Somaliland) during the Medieval Period by Jorge de Torres Rodríguez pg 549-562

Kola’s Kingdom: The Territory of Abasa (Western Somaliland) during the Medieval Period by Jorge de Torres Rodríguez pg 563-566

The town of Amud, Somalia by G.W.B. Huntingford

Exploring long distance trade in Somaliland (AD 1000–1900): preliminary results from the 2015–2016 field seasons by Alfredo González-Ruibal pg 149-152, 154-156)

The 2020 field season at the medieval settlement of Fardowsa (Somaliland) by Jorge de Torres Rodríguez et. al, City of Traders: Urbanization, Social Change, and Territorial Control in Medieval Fardowsa (Central Somaliland) by Jorge de Torres Rodríguez pg 88-98

City of Traders: Urbanization, Social Change, and Territorial Control in Medieval Fardowsa (Central Somaliland) by Jorge de Torres Rodríguez pg 99, 108)

An Archaeological Reconnaissance in the Horn: The British-Somali Expedition, 1975 by Neville Chittick 1975 pg 129-130)

Urban mosques in the Horn of Africa during the medieval period by Carolina Cornax-Gómez et Jorge de Torres Rodríguez p. 37-64, prg 31

Built on diversity: Statehood in Medieval Somaliland (12th-16th centuries AD) by Jorge de Torres Rodriguez pg 173-174, Kola’s Kingdom: The Territory of Abasa (Western Somaliland) during the Medieval Period by Jorge de Torres Rodríguez pg 572)

Asia in the Horn. The Indian Ocean trade in Somaliland by Alfredo Gonzalez-Ruibal et. al.

The Ruined Towns of Somaliland by A. T. Curle pg 322

City of Traders: Urbanization, Social Change, and Territorial Control in Medieval Fardowsa (Central Somaliland) by Jorge de Torres Rodríguez pg 87

In Search of Gendabelo, the Ethiopian “Market of the World” of the 15th and 16th Centuries by Amélie Chekroun, Ahmed Hassen Omer and Bertrand Hirsch

Kola’s Kingdom: The Territory of Abasa (Western Somaliland) during the Medieval Period by Jorge de Torres Rodríguez pg 563, 572.

Built on diversity: Statehood in Medieval Somaliland (12th-16th centuries AD) by Jorge de Torres Rodriguez pg, 176, 179).

The Spanish Archaeological Mission in Somaliland by Jorge de Torres pg 59, Urban mosques in the Horn of Africa during the medieval period by Carolina Cornax-Gómez et Jorge de Torres Rodríguez p. 37-64, prg 34

Islam in Ethiopia. By J. Spencer Trimingham pg 77, 91-95

Built on diversity: Statehood in Medieval Somaliland (12th-16th centuries AD) by Jorge de Torres Rodriguez pg 172, The Ruined Towns of Somaliland by A. T. Curle pg 319

Kola’s Kingdom: The Territory of Abasa (Western Somaliland) during the Medieval Period by Jorge de Torres Rodríguez pg 573

Kola’s Kingdom: The Territory of Abasa (Western Somaliland) during the Medieval Period by Jorge de Torres Rodríguez pg 549,

The town of Amud, Somalia by G.W.B. Huntingford pg 182, 184, The Ruined Towns of Somaliland pg 319, n.4

First Footsteps in East Africa By Richard Francis Burton pg 146

Built on diversity: Statehood in Medieval Somaliland (12th-16th centuries AD) by Jorge de Torres Rodriguez pg 185-187

Divine Fertility: The Continuity in Transformation of an Ideology of Sacred Kinship in Northeast Africa by Sada Mire pg 20-35, 52-63)

Divine Fertility: The Continuity in Transformation of an Ideology of Sacred Kinship in Northeast Africa by Sada Mire pg 64-68)

Islam in Ethiopia By J. Spencer Trimingham pg 85-97, Dakar, capitale du sultanat éthiopien du Barr Sa‘d addīn by Amélie Chekroun, A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly 108, Harar as the capital city of the Barr Saʿd ad-Dıˉn by Amélie Chekroun pg 27-28.

"According to Sheikh Abi-Bakr Ali Alawi, a medieval Harari historian, in his writings, Yusuf bin Ahmad al-Kawneyn—an individual of the Dir tribe—was the progenitor and founder of the Walashma Dynasty. The Dir tribe, recognized as one of the ancient noble Somali tribes, continues to have a significant presence in Zeila to this day. Sheikh Abi-Bakr Alawi affirms this connection in his book, stating that Yusuf bin Ahmad al-Kawneyn hailed from the local Dir clan and was instrumental in establishing the Walashma Dynasty."

(Source: Quath, Faati. Islam Walbaasha Cabra Taarikh [Islam and Abyssinia Throughout History], 1957)

Thank you for this solid work.