Matriarchs of the East African coast: Power, Property and the changing status of Women in the Swahili world (1300-1900 CE)

Historical traditions of several pre-colonial African societies are awash with stories of titled women who played prominent roles in the continent’s political history, such as the Candaces of ancient Kush and Queen Nzinga’s dynasty in Angola.

On the East African coast, internal accounts and European sources indicate that women wielded greater social and economic power than was possible later. They held political office, owned and inherited property, and oversaw important events concerning their kin groups.

Many coastal societies followed matrilineal principles of descent and inheritance, and nearly all of them followed a matrilocal residence rule where husbands moved into the homes of their wives.

In the later centuries, the expansion of Omani and European hegemony saw a consolidation of gender distinctions, resulting in the demotion of women from the sphere of politics, as public spaces became overwhelmingly male.

These shifting power dynamics, which were well documented in the modern period, were erroneously projected into the earlier centuries by colonial ethnographers. Contrary to the Western ‘orientalist’ images of secluded Muslim women, historical scholarship shows that the women of the Swahili world possessed significant social and economic agency, prompting a more nuanced understanding of their status.

This article examines the changing status of women on the East African coast from the late Middle Ages to the end of the 19th century.

Map of the Swahili world

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by joining our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Political authority and Queen regnants on the East African coast

The existence of women sovereigns, bearing the titles of Mwana or sultana, was common from the medieval period to the end of the 19th century on the Swahili coast and in the Comoros, attested as much by local chronicles as in European sources.

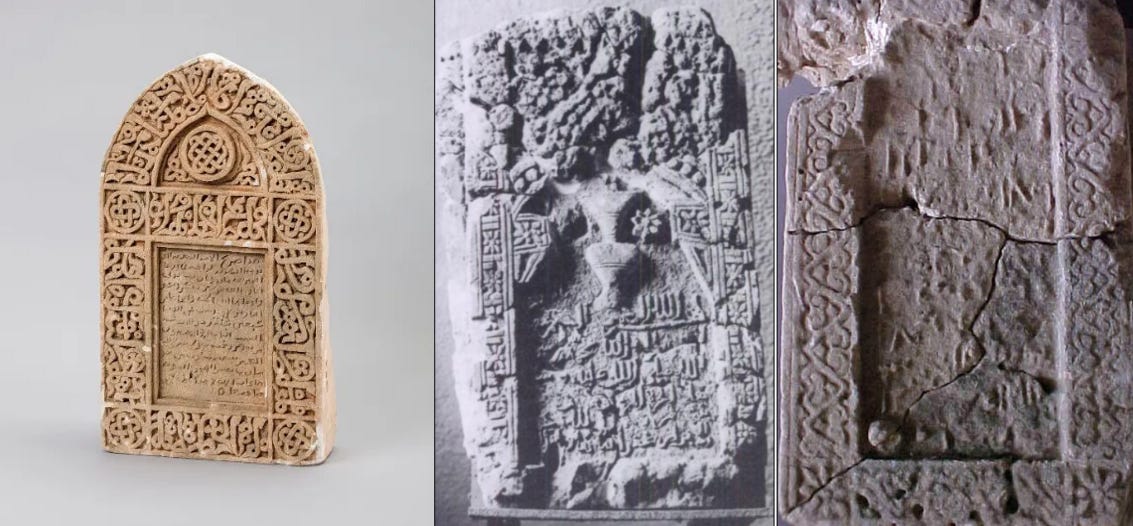

Sources document female leaders in Mombasa, Lamu, Pate, Siyu, Ngumi, Luziwa, and Kitau in Kenya, on Pemba, Tumbatu, Mafia, Zanzibar, and Kua in Tanzania, and at Mikindani near the border with Mozambique. The ubiquity of these references strongly suggests that women in positions of authority were not isolated occurrences. A considerable number of epitaphs dated to the late Middle Ages also commemorate titled women, some of whom had made the hajj.1

It is relevant to note that given the political organization of the Swahili cities, which were dominated by a Yumbe council/assembly of wazee elders/patricians, these queens (and Kings) were elected dignitaries presiding over a plurality of authorities in a parliamentary system similar to that found on the African mainland.2

The earliest records of titled females on the Swahili coast identify the pre-Islamic Queen Mwana Mkisi as the first ruler of Mombasa. The chronicle of Mombasa and other historical traditions of the city hold that she (or her dynasty) subsequently transferred authority to a male muslim ‘shirazi’ ruler, Shehe Mvita. These traditions encapsulate a rich and complex history of intermarriages, competition, and dynastic conflict that was common along the East African coast.3

Portuguese accounts mention that the ruler of Lamu in the mid-16th century was a woman. She reportedly became their ally during the Ottoman Portuguese wars and protected the Portuguese present in the town during the invasion of Ottoman corsairs in Lamu in 1546. The Ottomans sacked the town and captured the sovereign, but she managed to escape by swimming ashore.

While part of the story was embellished, this episode earned the queen the full consideration of the Portuguese crown: in the name of the king, who had promised that she would be amply thanked for this act of bravery. Francisco Barreto, the viceroy of Goa (India), gave her military honors and issued her navigation permits, offering great freedom of movement for her vessels.4

Thirty years later, in 1570, the Portuguese assisted the Queen of Lamu to retake her throne from the usurper Bwana Bashira, who was allied to the Ottomans. This Queen was the widow of the previous sovereign, who was also a Portuguese ally, and she had ascended to the throne upon his death. The Portuguese restored her with the consent of the wazee (“regedores”) of Lamu and other political leaders on the island.5

Mombasa, ca. 1572 by Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg

Mombasa, Kenya, ca. 1890

(left) 1462 epitaph of ‘Mwana wa Bwana binti mwidani’, from the Tuaca town in Mombasa, Kenya, Fort Jesus Museum. (right) Tombstone of an unnamed “free-born woman” from Kingany, Mozambique. Dated to the 14th-16th centuries. Image by Chantal Radimilahy

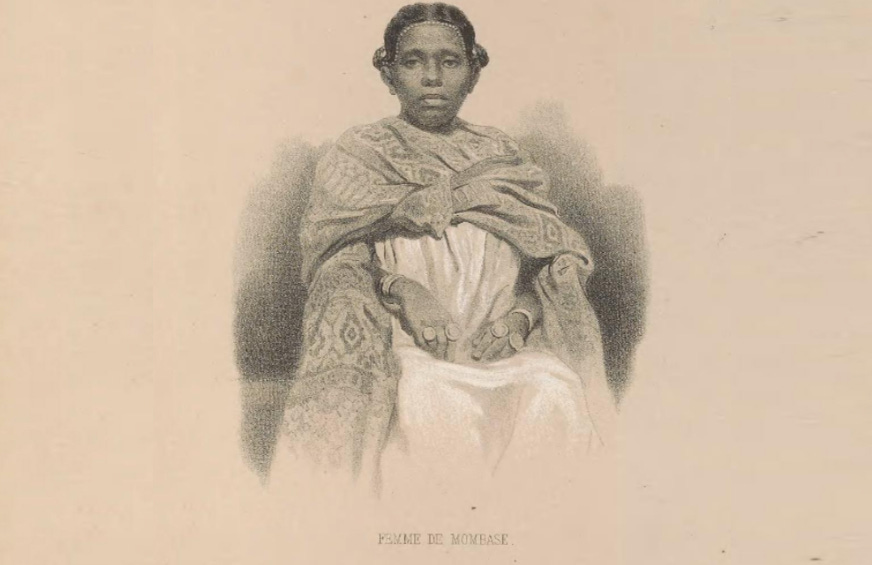

Woman of Mombasa. ca. 1856. Image by Charles Guillain.

Historical traditions and contemporary accounts of the late 16th to mid-17th century period mention several matrimonial alliances between the elite lineages of the main coastal cities and Sharifs of Hadrami origins who had been resident in the city of Pate in the Lamu archipelago. While most of these unions involved local ‘princesses’ from the dominant lineages, a few of them involved ruling Queens, especially on the island of Nzwani.

In the late 16th century, the ‘shirazi’ Sultan of Nzwani, Muhammad Mshindra, was succeeded by his daughter Halima, who was married to a Sharif from Pate. The earliest European accounts of Nzwani ( Anjouan/ Johanna) in 1599 mention that the island was ruled by a queen at Domoni, but unlike her peers in Kilwa and Zanzibar, she was secluded:

“We anchored at Ansuame [Ajouan], before a City named Demos [Domoni]: which hath beene a strong place, as by the ruines appeare. Their houses are built with free hewed stone and lime... This Queene used us exceeding friendly; but she would not be seene. The Inhabitants are Negroes, in Religion Mahometists, their weapons are Swords, Targets, Bowes and Arrowes... Here we found Merchants of Arabia and India.”6

In 1614, English voyagers found the aged Queen still on the throne of ‘Juanny’ (Anjouan), although her sons effectively ruled the island at Domoni and Mutsamudu. She’s referred to as “an ould woeman Sultanness of them all, to whom they repayre for Justice both in ciuill and criminall causes.” She installed her daughter and two of her sons on the neighbouring island of Moheli (Molalia), to ‘govern several parts of the island.’7

Around 1702, another Queen named Halima II was in power when the island’s second capital of Mutsamudu became a major port of call for English ships visiting the Indian Ocean. She was also married to a Sharif from Pate, and their sons succeeded to the throne by virtue of their membership of Halima’s matrilineage.8

Like in the Swahili cities, women frequently held positions of power in the Comoro archipelago either as Queen regnant with full authority or as regents.

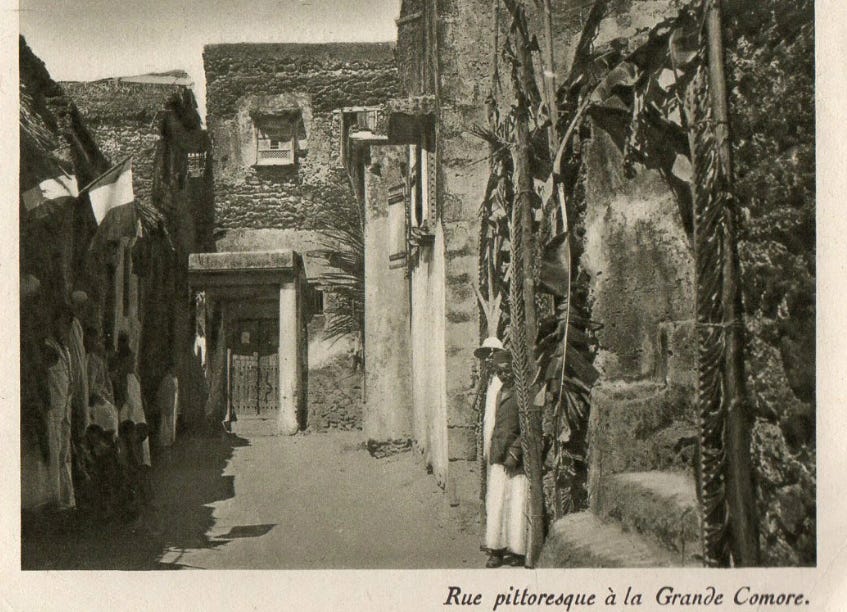

The repeated (and sometimes conflicting) reports of Nzwani being ruled by kings and queens would seem to reflect a struggle to impose different principles of succession on the island—the pre-existing matrilineal system and a patrilineal system brought by the Sharifs. The matrilineal system was fully retained in the larger island of Ngazidja (Grande Comore), where several Queens are also mentioned in the historical record.9

Gerezani Citadel, Itsandra, Grande Comore. images from MuzdalifaHouse. The structure was built by Itsandra Sultan Fumnau (r. 1743-1800), who was the grandson and successor of Queen Wabedja (ca. 1700-1743).

In the 17th century, a plethora of references identify female rulers along nearly the entire coast.

A number of queens ruled in Pemba during the 17th century, according to Portuguese sources and historical traditions. These include: Mwana Mize binti Muaba, Mwana Fatuma binti Darhash, Mwana Hadiya, and Mwana Aisha. Additionally, in the Lamu archipelago, there was Mwana Inali of Kitao (on Manda Island), who resisted the rulers of Pate, and Asha binti Muhammad, ruler of Ngumi, whose authority extended as far north as Port Durnford (Bir Gao) at the southernmost end of Somalia.10

In the second half of the 17th century, Stone Town in Zanzibar was ruled by Queen Mwana Mwema, who participated in revolts against Portuguese authority along the Swahili coast, instigated by an alliance with the Yaʿrubī dynasty of Oman.

In 1651, Mwana Mwema invited a Ya’rubid fleet, which killed and captured 50-60 Portuguese residents on the island, and she called for further reinforcements by sending two of her ships. However, the reinforcements didn’t arrive, and the elites of Kaole —stone-town’s rival city on the mainland— would ally with the Portuguese to force the Queen out of Zanzibar by 1652.11

Zanzibar later became an ally of the Portuguese, because a few decades later, another Queen of Stone Town named Fatuma binti Hasan, a granddaughter of Mwana Mwema, lived next door to the Portuguese church on the island at the time of the siege of Mombasa by the Omanis in 1698 CE. The southern city-state of Kilwa was also ruled by a Queen who was allied to the Portuguese, having welcomed fleeing Portuguese and helped them reach Cape Delgado in northern Mozambique.12

Aerial view of the Makutani Palace in Kilwa Kisiwani, Tanzania. Image by E. Ichumbaki. The Queen of Kilwa mentioned above restored the old ‘shirazi’ dynasty of the city that had been deposed by the ‘Mahdali’ dynasty in the 13th century. This palace was constructed around the time of her reign in the early 18th century.

In the early 18th century, the Queens of Zanzibar and Kilwa led a powerful coalition of Swahili rulers who sought Portuguese assistance to expel the Omanis.

Three years after the capture of Mombasa, the queen of Zanzibar fought the occupiers, and her daughter, Mwana Mtoto, who succeeded her after her death, also remained allied to the Portuguese. A letter she sent to Mozambique was intercepted by the Omanis, and her son, Mfalme Hasan, and two other “princes” were imprisoned by the Omanis in Muscat.13

Official letters written by the queen of Kilwa, Sultani Fatima binti Sultáni Mfalme Mohammed, to the Portuguese governor of Goa (India) show that the unrest between the inhabitants of Kilwa and the Omanis was particularly violent, and it is in these documents that the ‘Swahili’ ethnonym was first adopted by the coastal populations to assert their identity against the Arab interlopers.

The letters also reveal a deep anti-Omani sentiment. According to Sultáni Fatima and her supporters, the Omanis were hated all along the coast, and the rulers of Zanzibar, Pemba, Vumba, Tanga, Utondwe, Pambuji, Kendwa, and others were awaiting Portuguese support. In one letter, the Queen wrote: “Today the Arabs are hated, because everyone is disgusted by them.” In another letter, her daughter, Mwana Nakisa, described the Omani soldiers deployed in 1711 as “scabs, striplings, and weaklings.”14

letters written by Mfalme Fatima (queen of Kilwa), her daughter Mwana Nakisa, and Fatima’s brothers Muhammad Yusuf & Ibrahim Yusuf. ca. 1711. Goa archive, SOAS London.

The weakening of Oman after 1719 favored the brief re-conquest of the coast by the Portuguese in 1728, before the latter were ultimately expelled by the Swahili in 1729.

Omani authority wouldn’t be re-established until the 1840s, after they had been resident on Zanzibar for nearly half a century. Brava (Barawa), Lamu, Pate, Mombasa, Kilwa, and the Comoro islands would remain under local rule for most of the first half of the 19th century.

Power was retained by the established lineages and only rarely shared with the immigrant Sharifian and Omani families, eg, in Mombasa. In some cities, such as Kilwa, the old Shirazi lineages regained their authority. A letter from the Kilwa sultan to the French King in 1819 still shows the same hostility towards the Arabs (Omanis) as in the 1711 letter written by his ancestor, Queen Fatima.15

In 18th century Pate, a Queen named Mwana Khadija ruled from 1764 to 1773, and Mwana Darini, though not a ruler, played a significant role in Pate politics. Historical traditions indicate that the ruler of Kua was Queen Mwanzuani, who had succeeded her mother. Other scattered traditions refer to women sovereigns such as Mwana Masuru of Siyu, Queen Maryamu of Yumbwa, and an unnamed queen of Luziwa of uncertain date.

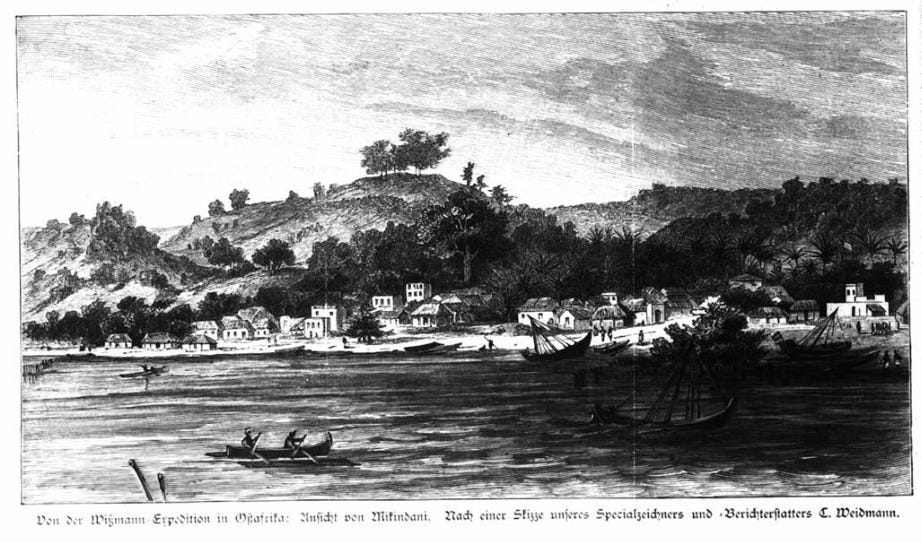

There were also a few titled women in the 19th century, eg, Fatuma binti Ali and Mwana Kazijabinti Ngwali, who ruled Tumbatu island (Zanzibar archipelago) in the early 19th century. Among the last known queens was Sabani binti Ngumi, a woman of mixed Swahili and Makonde descent who, in 1886, was recognised as “the chieftainess of Mikindani and her daughter was recognised as her successor.”16

View of Mikindani, Tanzania. ca. 1890. Koloniales Bildarchiv, Universitätsbibliothek Frankfurt am Main

Property and inheritance in the Swahili world

Ethnographic research from the 20th century indicates that kinship, succession, and inheritance in coastal communities were fluid, exhibiting aspects of patrilineal and bilateral systems. Most societies were characterized by the matrilocal/Uxorilocal rule of marital residence, where the husband comes to live in his wife’s house or near the wife’s family. According to the pioneering ethnographic work on the Swahili of Bagamoyo (Tanzania) during the 1890s by Mtoro Bakari, “free birth is matrilineal.”17

In Nzwani, since the husband was married into a house that was not his, he could build or renovate a house for his daughter to demonstrate his economic capacity and social status.

In Ngazidja, built plots and undivided agricultural land were called manyahuli and, like all property, were inherited by women. The use of public land in the hinterland (comprised of forests and uncultivated land) was allocated by village assemblies to men who do not have manyahuli land.18

‘Picturesque street in Grande Comore’ ca. 1930

In the 20th century, the basic plan of East African coastal houses is made up of two gendered spaces, following an “intimacy gradient” that led from public male-centered spaces to more private female-centred spaces.

Excavations in the back rooms of 18th- to 19th-century Swahili houses in Lamu and Pate found artefacts associated with the social roles and practices of Swahili women, suggesting that differential access to the various spaces of Swahili homes may be considerably old.19

However, excavations from late medieval sites like Songo Mnara display a different house plan with stepped courts surrounded by interior rooms, whose occupants weren’t secluded. The material remains found in these rooms suggest significant movement of both women and men through all these spaces.20

stepped courtyard in Songo Mnara, Tanzania.

The less ‘gendered’ layout of medieval Swahili homes was likely altered after the 16th century, following the influx of the Sharifs and Omanis along the coast, although this process is more visible in some cities than others and may have been very gradual.

In his very detailed description of the Nzwani capital, Mutsamudu in 1704, the English trader John Pike provides a house plan and a facade drawing that help explain the layout of the spaces, with a predominantly male reception area and courtyard, leading to the inner apartments of the woman and her entourage. The house extended from east to west with an airy courtyard lined with trees that served as an audience hall, while the women’s rooms were in the back.21

In other post-medieval Swahili cities, the basic layout of houses in both urban and rural settlements was broadly similar, although the materials used in construction were different. [See my previous article on Swahili architecture.] The innermost rooms were mostly reserved for women and were entered through a more public room leading to the exterior. Larger houses contained internal courtyards, multiple rooms with decorated niches (zidaka), and an upper terrace.22

Upper terraces lead to interconnected roofs, allowing women to move from house to house without having to go into the streets. At times, second-storey rooms would be connected to adjacent houses through doorways or rooms bridging over the streets, connecting members of the same family and allowing upper-class women to travel without having to venture into the male-dominated public spaces of the city.23

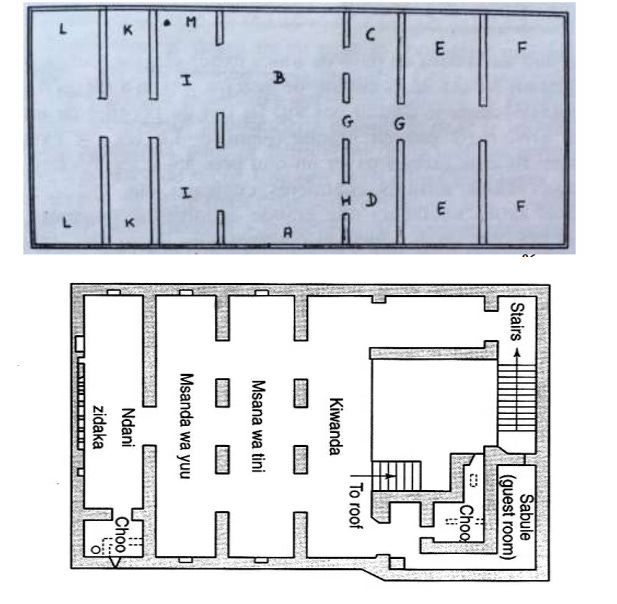

(top) Plan of a House in Nzwani by John Pike, ca. 1701. (bottom) first floor of a 19th-century house in Lamu, Kenya, by E. Pollard

Historical records from the late 19th century indicate that Women owned and rented out their houses when necessary, but also testify to the difficulties of female property ownership. Property ownership provided income for wealthier women, but property had to be managed and protected, and secluded women were ill-fitted for these tasks.

Records of land office transactions from 1891 to 1919 and other historical data from Mombasa and Malindi show that women owned property. These were often inherited from their maternal ancestors, but were at times managed by their male relatives when the women were still young. Other examples from the early 20th century indicate that women of all classes, both free and enslaved, owned real estate, including stone houses, furniture, and agricultural estates.24

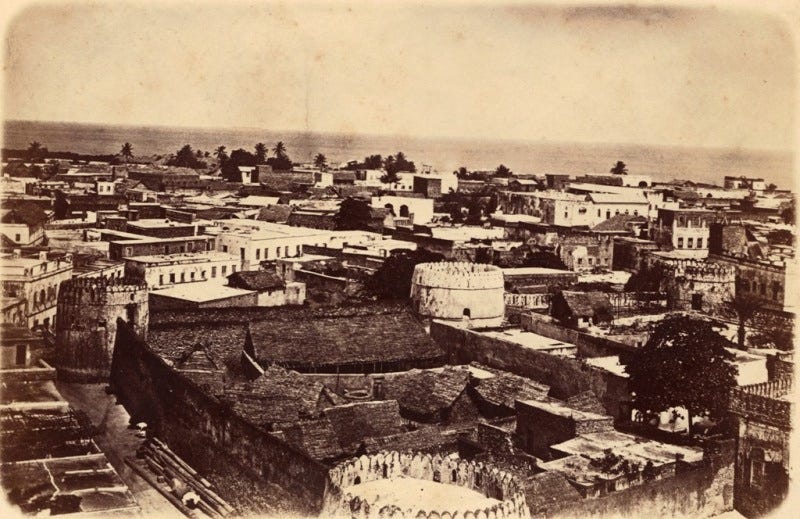

Zanzibar rooftops, ca. 1875

Changing status of women: inheritance, veiling, and women’s roles in Swahili literature

The declining position of women in coastal politics and their seclusion from public life was the result of a growing restriction on female roles during the Omani period and the early colonial era from the 18th century to the early 20th century:

Describing ownership of ‘Kiambo land’ (family building sites and estates) in the northern parts of the Zanzibar island during the 1950s, the anthropologist A. H. J. Prins noted:

“Women also belong to this category of owners , and in case a man contracts for some reason an uxorilocal marriage he , as a husband , has rights of usage and building . In some areas, though the husband cannot inherit , children can through their mother, thus making a breach in an alleged patriline of succession to land rights . Where the influence of the Sharia [Islamic Law] as against customary law has been strong, a husband too becomes heir to his deceased wife.”25

He adds that these lands, which are under the traditional custom where widowers couldn’t inherit from their deceased wives, “are in a minority nowadays,” especially when compared to the ‘more developed’ western parts of the island, where the Omani rulers were based, and Islamic law prevailed.

Besides the shifts in land ownership, historical evidence indicates a trend of lower-class women adopting the purdah (veil) to enhance their respectability, in imitation of upper-class women, who were increasingly secluded from public life.

Early descriptions of the fashion of coastal women in Portuguese accounts make numerous references to their jewellery and silk or cotton garments, but don’t mention the use of the veil or other head coverings.26

In Nzwani, multiple visitors from the 17th to 19th centuries reported the excessive “jealousy” of the islanders (keeping women indoors), which the visitors attributed to their religion, since the elites had adopted the more orthodox Sharifian practices. However, seclusion and the wearing of the veil were expressions of a class relationship that distinguished the elites and the rest of the subjects. Non-elite women remained active in public spaces, including markets and farms.27

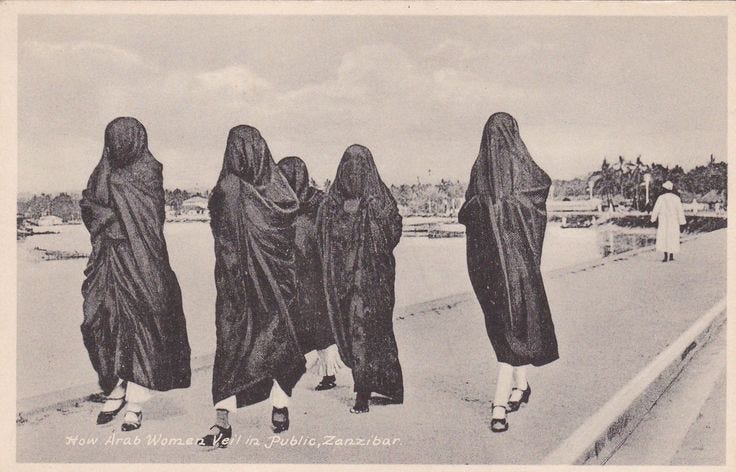

Mombasa women in the 1840s were more casual than Zanzibaris regarding the purdah, claimed one observer, because of the smaller number of Arabs in Mombasa, although upper-class women travelled in the streets covered under a cloth known as the ramba in Mombasa and the shiraa in Lamu. Even in Zanzibar during the 1850s, where Arab women wore a black Omani veil, freeborn Swahili women “mostly [went] abroad unveiled,” but wore a long indigo covering called the ukaya.

The ukaya would later fall out of fashion among the Zanzibari Swahili in the 1870s, but was adopted by formerly enslaved women to increase their respectability. It was replaced by the wearing of a buibui, brought by immigrants from Hadramawt, which consisted of a black cotton or silk wrapper that covered the entire body. However, this new fashion took a long time to catch on, as upper-class women were still unveiled in most photographs from the early 20th century.28

The autobiography of a Zanzibari-Arab princess in 1888 indicates that Women and Men enjoyed the same rights, but notes that religious rules on female seclusion during the late 19th century applied more strictly to upper-class women than their lower-class peers:

“Ladies of higher rank often envy their poorer sisters on account of their advantages.”29

Additionally, other social practices like dances, weddings, initiation ceremonies, and spirit possession cults were frequented by all classes of women, and offered one of the very few opportunities for upper-class women to engage in public life. Mtoro Bakari’s account also shows that both men and women participated in these dances, contrary to contemporary practice, where the dances are reserved for women.30

‘How Arab women veil in Public’ Zanzibar, Tanzania.

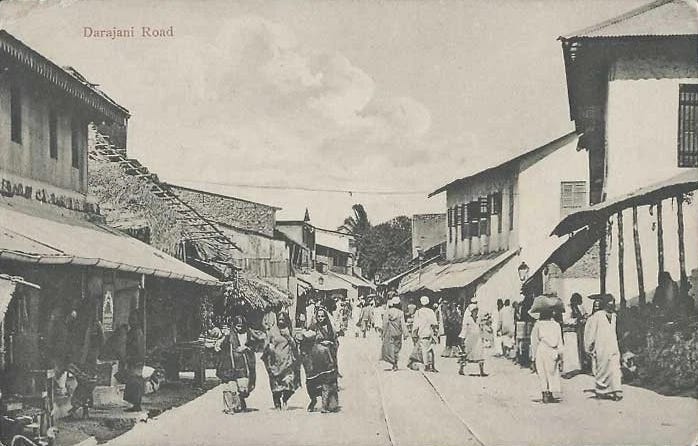

Women and men in the street, Zanzibar, Tanzania. early 20th century

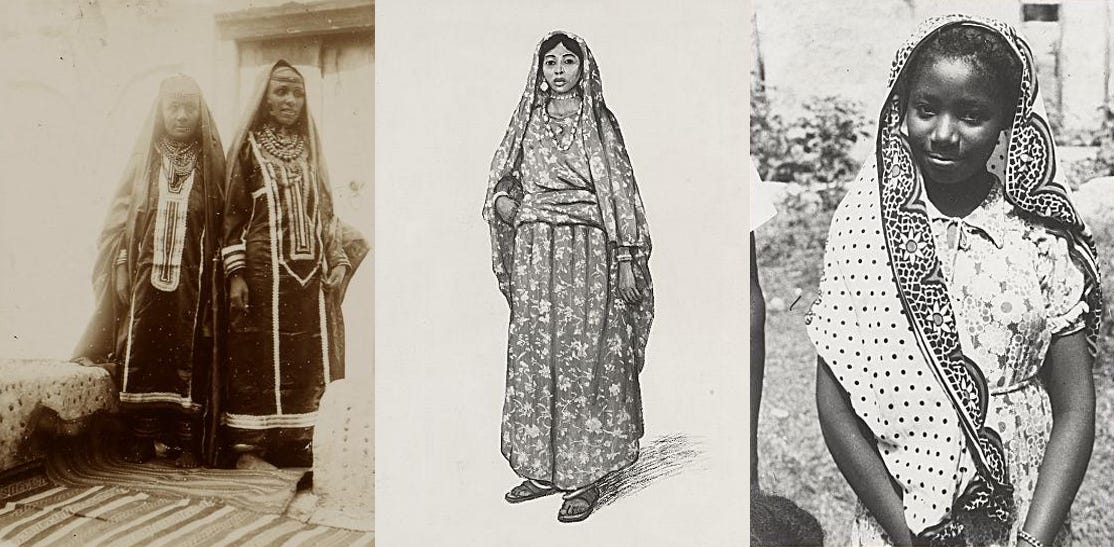

Comorian princesses, ca. 1890-1896, Painting of a Comorian woman by Lucien Lièvre, ca. 1900, Comorian girl from Mayotte. ca. 1952. ANOM

‘Native Women picking rice.’ Zanzibar, Tanzania. early 20th century.

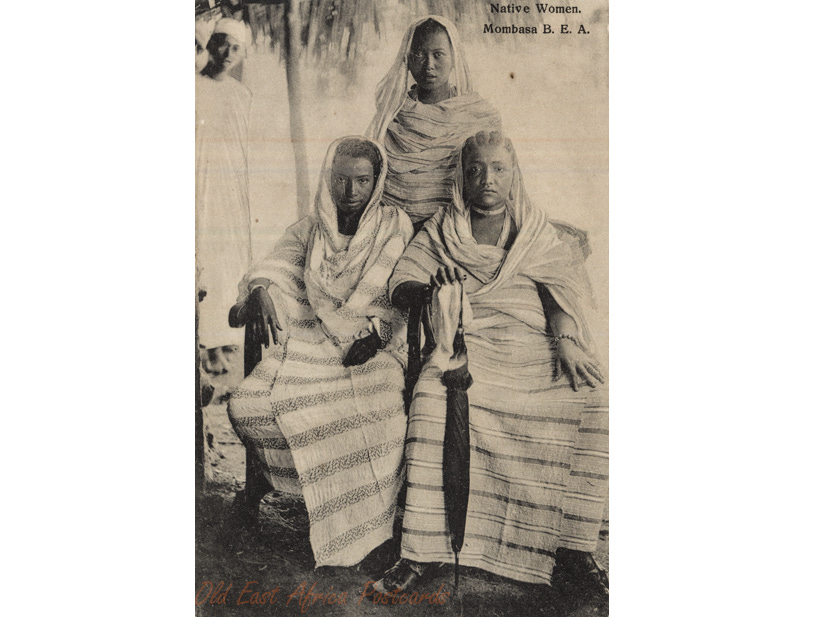

“native women Mombasa B.E.A.” ca. 1908.

According to Prita Meier, this rare postcard of three elite Mombasan women contrasts sharply with the more popular studio portraits of ‘Swahili women’ from Zanzibar, which often featured staged scenes. It was likely commissioned by the women rather than by the photographer, but was later turned into a postcard. The women’s clothing and sandals mark them out as freeborn, and their poses reflect patrician codes of decorum and respectability.31 (the same pose can be seen below)

Patricians (Waungwana) sitting in state in a richly decorated reception room in Lamu Town, Kenya. ca. 1884, National Library of Scotland

Representations of women in Swahili literature, especially in classical poetry from the 17th to 20th century, are complex and multidimensional. Like in many muslim societies, most written works from the East African coast are concerned with religious topics. These include works by women authors such as “Siri al-asari” (The secret of the secrets), composed in 1663 by Mwana Mwarabu bint Shekhe, the utenzi of “Mwana Fatuma” (The Epic of Princess Fatuma), composed in 1807 by Mwana Said Amini, and many others from the 20th century.32

A particularly exceptional work composed in the 19th century was the “Utendi wa Mwana Kupona” (Mwana Kupona’s poem), which was written by Mwana Kupon bint Msham (b. 1810- d.1860) in Siyu, Kenya. It’s a didactic poem dedicated to her daughter, principally to offer her advice on relationships between wives and husbands. The poem has inspired widely divergent interpretations, but it mostly reflects the prevailing values among upper-class coastal Muslims in the 19th century that placed women in a subordinate position to men.33

Mwana Kupona’s swahili poem; “Utendi wa Mwana Kupona.” Berlin state Library

Its important to note that Mwana Kupona’s portrait of an ideal home contrasts sharply with the reality of family life at the coast that’s described in other sources, which suggests that women were less constrained by such orthodoxies, especially the non-elites who comprised the majority of the population.

Reports by multiple visitors and later colonial officials indicate that the ownership of their homes offered women security and weakened the reality of male dominance. Among the Swahili in the late 1860s, the missionary Edward Steere observed that:

“It is the rule on the Swahili coast that the bride’s father or family should find her a house, and that the husband should go to live with her, not she with him... Among poor people many have only one wife, and her house is their home.”34

Describing the marriage customs of the lower classes and slaves in Zanzibar during the 1870s, the traveler Charles New observed that:

“The woman provides house and furniture. In her house she is queen. Should her husband dare to offend her, she at once reminds him that she is mistress, that the house and furniture are hers; and that if he is not satisfied with the treatment he receives, he can leave and make room for someone else. The insulted and Indignant man seizes his stick, or his sword, and flees from the termagant to seek a home elsewhere.”35

While the latter description was embellished and intended to shock his Victorian audience (apparently, to frighten those advocating for women’s rights in Britain by showing them what women would do with those rights), accounts by colonial officials about the relative freedom of Swahili women in domestic contexts suggest that the more rigidly dictated gender roles and wifely obedience were more apparent than real.36

Women’s status underwent further transformation during the colonial and post-colonial period, as a consequence of social dislocation and ideological conflicts between the mostly Christian government and the Muslim authorities, which are beyond the scope of this article.

The above analysis shows that the position of women in the social hierarchy of the Swahili world changed over the centuries, highlighting how their status varied considerably between different classes and social groups.

The historical evidence also reveals the contradictions between social-religious ideals/laws and cultural practices, which ultimately influenced the dynamics of gender relations in pre-colonial African societies in ways similar to other parts of the world.

My latest Patreon article explores the parliamentary democracies of pre-colonial Tswana kingdoms in southern Africa, which are among the most enduring forms of indigenous African democratic institutions.

Please subscribe to read about it here, and support this newsletter:

Female Circles and Male Lines: Gender Dynamics along the Swahili Coast by Kelly M. Askew, pg 81-82, History of East Africa, Vol. 1, ed. by Roland Oliver and Gervase Mathew, pg 167, Writing in Swahili on Stone and on Paper by Ann Biersteker

Les cités-États swahili de l’archipel de Lamu, 1585-1810: dynamiques endogènes, dynamiques exogènes by Thomas Vernet pg 103-104

Oral Historiography and the Shirazi of the East African Coast by Randall L. Pouwels pg 252-253, The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria LaViolette pg 52

Les cités-États swahili de l’archipel de Lamu, 1585-1810: dynamiques endogènes, dynamiques exogènes by Thomas Vernet pg 91

Les cités-États swahili de l’archipel de Lamu, 1585-1810: dynamiques endogènes, dynamiques exogènes by Thomas Vernet pg 105, 117

The Voyage of Captaine John Davis to the Easterne India, Pilot in a Dutch Ship, written by himself, edited by Albert Hastings Markham, pg 138

The Embassy of Sir Thomas Roe to the Court of the Great Mogul, 1615–1619, As Narrated in His Journal and Correspondence, Issue 1 by Sir Thomas Roe

Islands in a Cosmopolitan Sea: A History of the Comoros by Iain Bruce Walker, pg 60, 67

Islands in a Cosmopolitan Sea: A History of the Comoros by Iain Bruce Walker, pg 67-68)

Female Circles and Male Lines: Gender Dynamics along the Swahili Coast by Kelly M. Askew, pg 83

Les cités-États swahili et la puissance omanaise, 1650-1720 by Thomas Vernet pg 92, Les cités - États swahili de l’archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 301-302, Excavations at the Old Fort of Stone Town, Zanzibar by Timothy power and Mark Horton, pg 281

The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria LaViolette, pg 243, 530, Les cités-États swahili et la puissance omanaise, 1650-1720 by Thomas Vernet pg 101

Ivory and Slaves in East Central Africa: Changing Pattern of International Trade in East Central Africa to the Later Nineteenth Century by Edward A. Alpers pg 72

Les cités-États swahili et la puissance omanaise, 1650-1720 by Thomas Vernet pg 104-106, Ivory and Slaves in East Central Africa: Changing Pattern of International Trade in East Central Africa to the Later Nineteenth Century by Edward A. Alpers pg 73

Un projet d’alliance entre Kilwa et la France contre l’expansionnisme omanais, étude d’une lettre en arabe de mfalme Sulaymān b. Ḥasan à Louis XVIII by Abdelhakim Belhacel and Fu’ad Al-Qaisi

Female Circles and Male Lines: Gender Dynamics along the Swahili Coast by Kelly M. Askew, pg 84

The World of the Swahili: An African Mercantile Civilization by John Middleton pg 99-101, 135-136, La maison urbaine, cadre de production du statut et du genre à Anjouan (Comores), XVIIe-XIXe siècles by Sophie Blanchy pg 2, Female Circles and Male Lines: Gender Dynamics along the Swahili Coast by Kelly M. Askew pg 85-88

La maison urbaine, cadre de production du statut et du genre à Anjouan (Comores), XVIIe-XIXe siècles by Sophie Blanchy pg 6. Cités, citoyenneté et territorialité dans l’île de Ngazidja (Comores) by Sophie Blanchy Prg 41

The public life of the Swahili stonehouse, 14th–15th centuries AD by Stephanie Wynne-Jones

A Material Culture: Consumption and Materiality on the Coast of Precolonial East Africa by Stephanie Wynne-Jones 165-166

La maison urbaine, cadre de production du statut et du genre à Anjouan (Comores), XVIIe-XIXe siècles by Sophie Blanchy pg 12-13

La maison urbaine, cadre de production du statut et du genre à Anjouan (Comores), XVIIe-XIXe siècles by Sophie Blanchy pg 7-12, The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria LaViolette pg 511)

The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria LaViolette pg 510

Muslim Women in Mombasa, 1890-1975 by Margaret Strobel Pg 58-73, La maison urbaine, cadre de production du statut et du genre à Anjouan (Comores), XVIIe-XIXe siècles by Sophie Blanchy pg 35-36.

The Swahili-Speaking Peoples of Zanzibar and the East African Coast (Arabs, Shirazi and Swahili) East Central Africa Part XII by A. H. J. PRINS

The East African Coast. Select Documents from the First to the Earlier Nineteenth Century by G.S.P. Freeman-Grenville

La maison urbaine, cadre de production du statut et du genre à Anjouan (Comores), XVIIe-XIXe siècles by Sophie Blanchy pg 24-28

Muslim Women in Mombasa, 1890-1975 by Margaret Strobel pg 74-75

Memoirs of an Arabian Princess, an Autobiography By Emilie Ruete

Female Circles and Male Lines: Gender Dynamics along the Swahili Coast by Kelly M. Askew, pg 67-69, Entre l’Afrique et l’Arabie : les esprits de possession sawahili et leurs frontières by Maho Sebiane)

The Surface of Things: A History of Photography from the Swahili Coast By Prita Meier pg 94

The Swahili Novels of Tanzanian Women: Agency, Tradition, and Change By Izabela Romańczuk

Muslim Women in Mombasa, 1890-1975 by Margaret Strobel, pg 84-90

Swahili Tales, as told by natives of Zanzibar. With an English translation by Edward Steere

Life, Wanderings and Labours in Eastern Africa: With an Account of the First Successful Ascent of the Equatorial Snow Mountain, Kilima Njaro, and Remarks Upon East African Slavery by Charles New

Muslim Women in Mombasa, 1890-1975 by Margaret Strobel, pg 91-94, Three Swahili Women: Life Histories from Mombasa, Kenya edited by Sarah Mirza, Margaret Strobel

Illuminating, as always. Grateful for the work you do, work that enlightens us. 🙏🏽

Great content as usual