Parliamentary systems and other pluralistic institutions in pre-colonial Africa

The political history of several African kingdoms included systems of governance that were variously referred to as national “assemblies”, “councils,” or “parliaments,” which limited the power of Kings.

In their description of the political structures in pre-colonial Asante, the British envoys Thomas Bowdich (1817) and John Dupuis (1820) provided reports on the operations of the kingdom’s “state council” and “palace council.” The former of which was a public assembly, while the latter consisted of powerful officials “composing the Privy council or Aristocracy, which checks the King.”1

Bowdich also explains the function of the Inner Council. It is they, he wrote,

“whom the king always consults on the creation or repeal of a law; whose interference in foreign politics or in questions of war or tribute amount to a veto on the king’s decision; whose chief, Amanquatea, like the ancient Mayors of the Palace, can alone sanction the accession even of the legitimate heir to the throne (who must await his presence however procrastinated), and whose power as an estate of the government always keeps alive the jealousy of the General Assembly [the Asantemanhyiamu].”2

According to the historians Ivor Wilks and Tom McCaskie, the Asante national assembly (Asantemanhyiamu) emerged in the early 18th century as a gathering of office holders who exercised a very broad oversight in fundamental matters of constitutional and state business.

By the late 18th century, power was centralised by the palace council/inner council at the capital Kumasi, which took over the executive and legislative functions of the kingdom. The function of the national assembly was confined to more fundamental constitutional and juridical issues, and debating measures that had originated in Kumasi.3

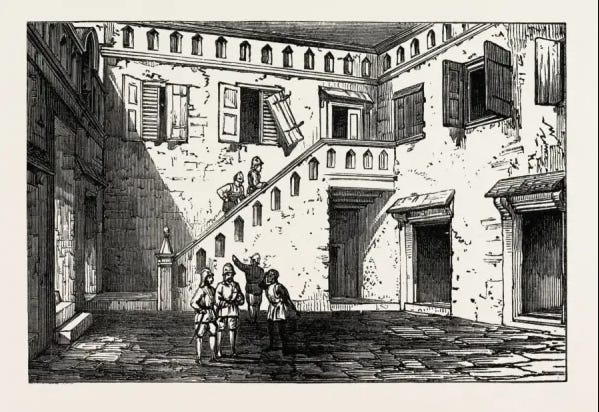

The ‘Aban’ stone palace of Kumasi, ca. 1874. image taken after the city’s capture by the British. According to the accounts of Bowdich and Dupuis, the palace was not used regularly as a royal residence, but had a semi-public function. The Asante king and his closest councilors at times met with foreign delegates in this structure and offered them a tour of their ‘museum’. [see my previous essay on Asante architecture ]

Similar institutions are documented across multiple African societies.

In the empire of Oyo (Nigeria), the power of the king (Aláàfin) was balanced by the òyómèsì, a seven-person state council comprised of the heads of prominent lineages in the capital. They met with the king in the palace to make all laws and take the highest decisions of government, including the election of a new king from a pool of royal candidates. When they were dissatisfied with the reigning king, they could order his deposition by instructing him to take his own life.

In the Hausa city-state of Kano (northern Nigeria), the 15th-century king Rumfa established the Kano state council of nine executives ( “Tara ta kano” ), which was partly modelled on the “council of twelve” of its suzerain, the empire of Bornu. This council functioned as a decision-making body on virtually all matters of foreign and domestic administration, but also acted as an electoral body that could appoint or depose kings.

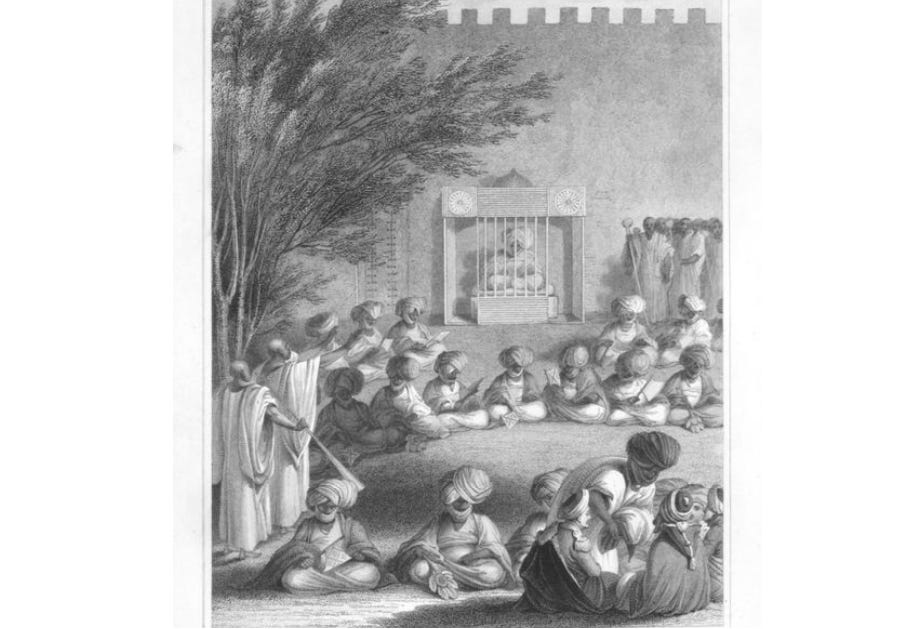

Reception of Dixon Denham at the court of the Shehu (Sheikh/Ruler) of Bornu. ca. 1822-4, Kukawa, Nigeria.

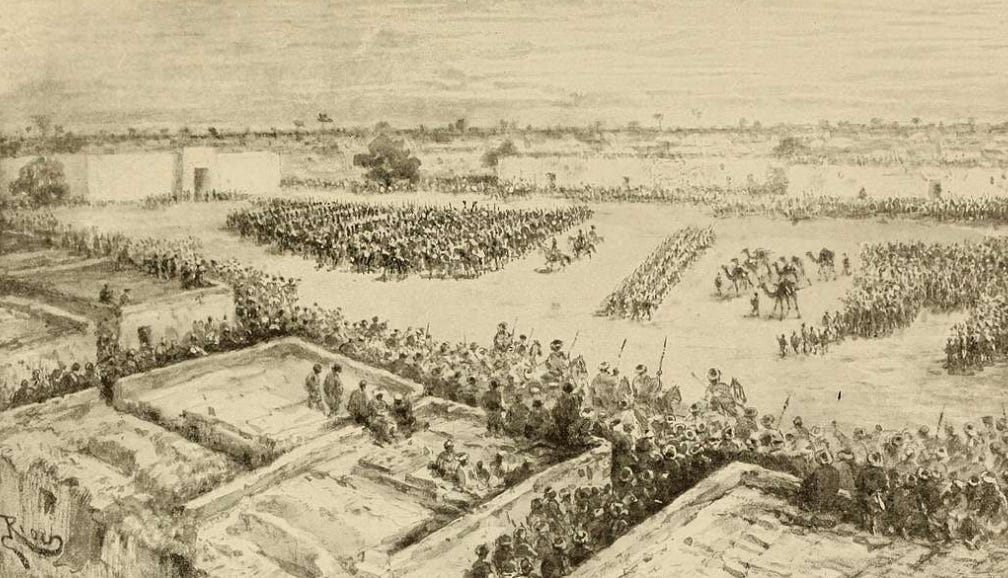

Reception of Monteil by Bornu’s courtiers, army, and spectators at Kukawa, Nigeria. ca. 1891. Monetil’s small party of less than a dozen was reportedly greeted by about 40,000 spectators, with a procession that led to the gate of the Sheikh’s palace (on the left), where his courtiers were waiting, while the Sheikh was observing the procession from an upper-story window. Monteil mentions that the Sheikh’s power had reduced considerably relative to that of his councilors, most notably, the Ghaladima, who “dealt with affairs not as a submissive vassal, but as an equal.”4

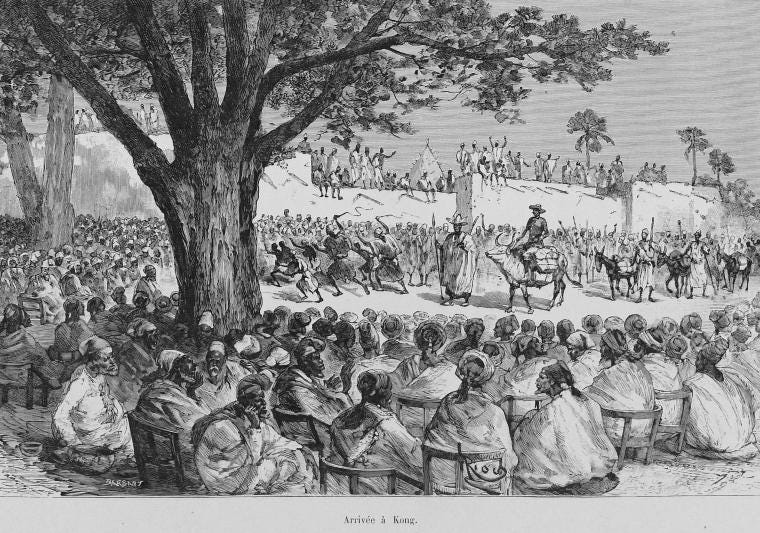

The two councils of Kong, receiving the French officer Louis Binger in 1892

According to Binger, the government of Kong (in Cote D’ivoire) consisted of two administrative bodies; one led by the Watarra royals and nobility, who were descended from the founder Sekou Watarra, and one led by the Dyuula scholars, whose leader was Karamoko Oule. Both councils and their leaders were present on his arrival in 1892: “Sékou left many descendants spread throughout the territory, and who all have a small command, which does not prevent them from recognizing the absolute authority of Karamokho-Oulé and the djemmâa (scholars) of Kong, a sort of council of elders of which Karąmokho-Oule is the president and the executive power.”5

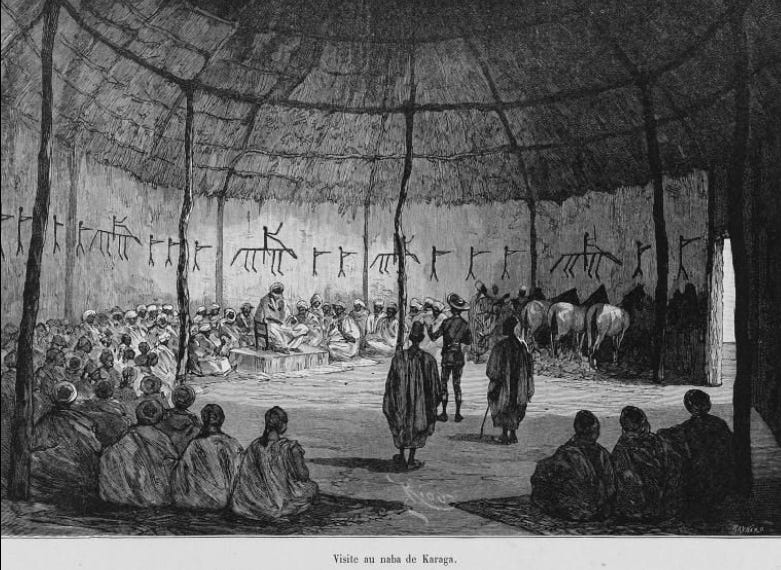

‘Visit to the Naba of Karaga’, ca. 1892, northern Ghana. Karaga chiefs meeting Louis-Gustave Binger inside a large thatched structure that served as a public hall.

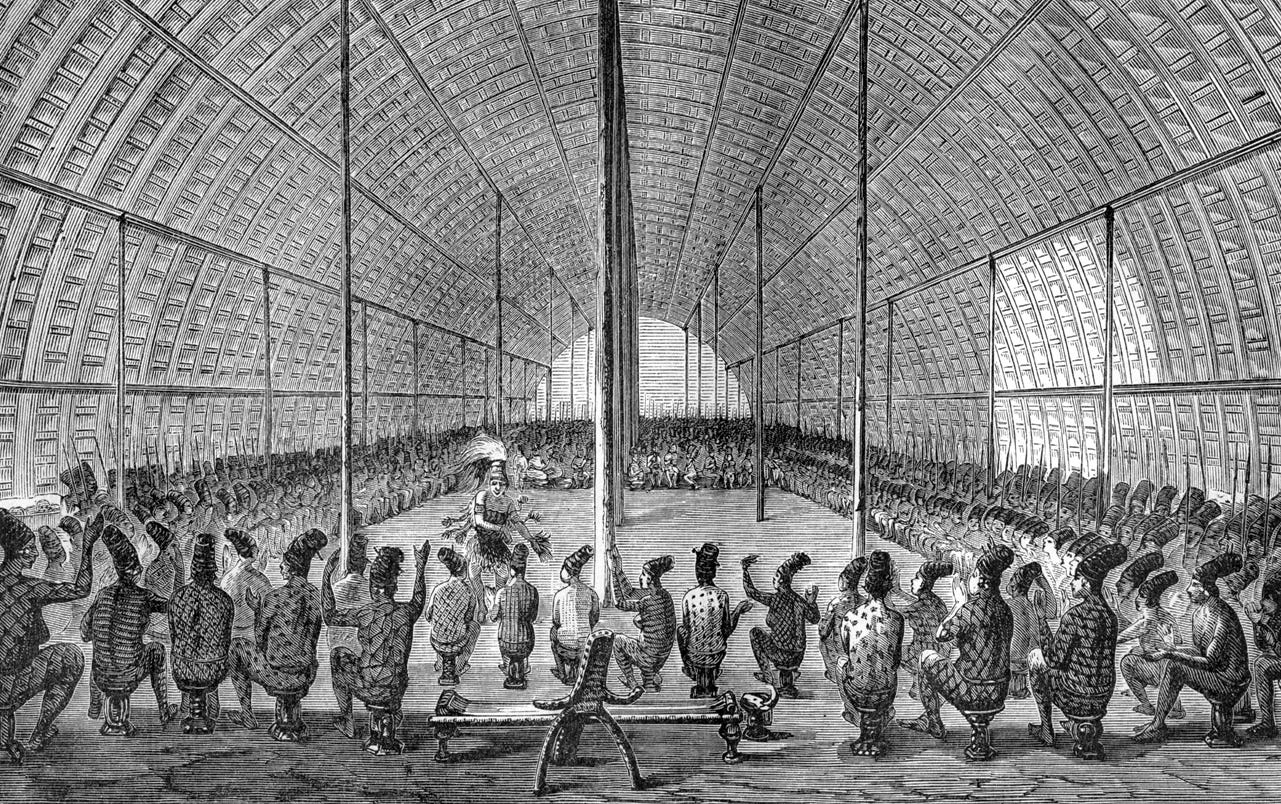

Public hall of the Mangbetu kingdom, north-eastern D.R.Congo. ca. 1870, illustration by Georg Schweinfurth.

In the kingdom of Kongo (northern Angola), a royal council was in charge of electing the monarch and the general administration of the kingdom. While mostly drawn from the nobility, the structure of the council could change, and its power fluctuated greatly. wars could not be declared, officials named or deprived, roads opened or closed without the consent of the council.

In the neighbouring kingdom of Loango (Rep. of Congo) during the 17th century, the king could not “do anything without the Council of four primates of his court.” These constituted an electoral council which determined the succession, as “they could raise one [king] up and replace him with another at their pleasure.”6

By the 18th century, the Loango council became so influential that when the King died in 1787, they were reluctant to elect another King, choosing instead to take over the administration of the kingdom for nearly a century.

Historical accounts of the Swahili cities such as Mombasa (Kenya), Lamu (Kenya), and Brava (Somalia) in the 16th century describe them as ‘republics’ that were governed by a council (Yumbe) of elders (wazee) or patricians (waungwana). Later accounts at times mentioned ‘Kings’ and ‘Queens,’ who were more accurately known as the ‘mwenye mui’ in Lamu or the tamim (spokesman) in Mombasa, and were chosen by a council of elders.

The state councils of the Swahili cities were in charge of the town’s administration; they adjudicated legal rows, provided political leadership, called town meetings, and supervised religious events.7

In the Comoros archipelago, the choice of the sultan was elective, with candidates being drawn from the ruling matrilineage. The sultan was assisted by a council comprised of heads of lineages and other patricians, which restricted his powers through assemblies. These assemblies convened in a public square known as a bangwe, with monumental gates (mnara) and benches (upando) where customary activities took place and public meetings were held.

View of Moroni, Grande Comore. ca. 1900, ANOM. with the ‘Bangwe’ in the middle ground

Gate and benches of the Bangwe Funi Haziri, Iconi, Grande Comore.

The development of political centralization and collective decision-making institutions was thus fairly common in pre-colonial African societies, with varying degrees of pluralism.

This is most evident among the kingdoms of the Tswana-speakers in southern Africa, whose pre-existing institutions of parliamentary democracy, known as the Kgotla/Pitso, contributed to the exceptional performance of the democratic institutions in modern Botswana.

Visitors in the 1820s were struck by the civic order of the Tswana capitals, and the freedom of speech allowed in the Kgotla, which they refer to as a ‘parliament’:

“The King’s power, though very great, is nevertheless controlled by the minor chiefs, who in their pichos or pitshos, their parliament, use the greatest plainness of speech in exposing what they consider culpable or lax in his government. These assemblies keep up a tolerable equilibrium of power between the chiefs and their king…

Such is the freedom of speech at those public meetings, that some of the captains have said of the King, that he stupifies his mind by smoking tobacco, and is not fit to rule over them.”

While some scholars, such as Acemoglu and Robinson, describe these institutions as exclusive to Botswana and claim that they were preserved in pristine form into the modern period, historians have highlighted the presence of similar institutions across the region, as well as the transformation of the Kgotla in Botswana from the pre-colonial period to the modern era.

The parliamentary democracies of pre-colonial Tswana kingdoms and their evolution are the subject of my latest Patreon article. Please subscribe to read about it here, and support this newsletter:

Journal of a Residence in Ashantee. By Joseph Dupuis, Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee by Thomas Edward Bowdich

Essay on the Superstitions, Customs, and Arts Common to the Ancient Egyptians, Abyssinians, and Ashantees by Thomas Edward Bowdich

State and society in pre-colonial Asante By T. C. McCaskie, pg 146, Asante- in the Nineteenth Century: The Structure and Evolution of a Political Order by Ivor Wilks, pg 387-395)

De Saint-Louis a Tripoli par le Lac Tchad : voyage au travers du Soudan et du Sahara accompli pendant les années 1890-91-92 by P. L. Monteil

Du Niger au Golfe de Guinée par le pays de Kong et le Mossi. by: Binger, Louis Gustave

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. Thornton, pg 178

Horn and Crescent: Cultural Change and Traditional Islam on the East African coast, 800-1900 by Randall L. Pouwels, Pg 83-85

Excellent essay. I'm also writing an article on royal councils in Africa based on Cheikh Anta Diop's book "Pre-colonial Black Africa". I'd love to send you a draft of this piece

Botswana had KGOTLA system