Stone towns on the Highveld of South Africa: an archaeological history of the Sotho-Tswana capitals (ca. 1450-1850)

The eastern plateau of South Africa, known as the Highveld, is dotted with the ruins of numerous stone towns founded at the end of the Middle Ages.

These pre-colonial capitals are some of the most visually striking built environments in southern Africa, and were, before their destruction, the largest urban settlements in the region, rivaling the colonial capital of Cape Town.

While Iron Age archaeology of southern Africa was initially concerned with the older and better-known ruins of Great Zimbabwe and Mapungubwe, a growing number of researchers have broadened their focus to take in sites farther south in the pre-colonial societies of the Sotho-Tswana speakers.

This article outlines the archeological history of the stone towns on the Highveld and explores the reasons for their abandonment in the early 19th century.

Map of South Africa showing some of the largest stone ruins in the HighVeld.1

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more on African history and keep this blog free for all:

The stone towns of the northern Highveld

The pre-colonial capitals of the various polities on the Highveld were described as large and densely populated when they first appeared in the documentary record during the early 19th century. Many of the first visitors who encountered these agglomerated settlements which were predominantly inhabited by speakers of the Sotho-Tswana languages, were often impressed by their scale and organization.

In 1820, the traveler John Campbell referred to Kaditshwene as a city2, while Robert Moffat in 1843 described a more northerly Tswana capital as a metropolis and was “greatly surprised on beholding the number of towns which lay scattered in the valleys.”3

Another account by Arbousset and Daumas in 1836, which describes the capital of the Tlokoa polity, notes that “Their capital, Merabing, is built on the summit of a mountain. this stronghold is approached by two openings on the western side, which are very appropriately called Likorobetloa, or the hewn gates. These are narrow passages defended on both sides by strong walls of stones in the form of ramparts. By this simple defence, added to the work of nature, the inhabitants of Merabing have been enabled to sustain many protracted sieges. In time of peace the town numbers thirteen or fourteen hundred inhabitants; but in time of war it affords protection to a far greater number, who flee thither from the neighbouring kraals.”4

Descriptions of these capitals leave little doubt that they correspond to the present ruins found all over the Highveld, some of which were already abandoned by the early 19th century.

Moffat's account mentions that he encountered “the ruins of innumerable towns, some of which were of amazing extent... The ruins of many towns showed signs of immense labour and perseverance; stone fences, averaging from four to seven feet high, raised apparently without mortar, hammer or line. The raising of the stone fences must have been a work of immense labour, for the materials had all to be brought on the shoulders of men, and the quarries where these materials were probably obtained were at a considerable distance.”5

Archeological research has shown that at the end of the 15th century, the Highveld region south of the Vaal River saw dense concentrations of agropastoralist settlements, with economies based on cereal cultivation (mainly sorghum and millet) and livestock transhumance. Initially, their building traditions featured wood-and-pole and dry-walled stone construction, but by the early 18th century dry-stone became the most prevalent architectural material in the region.6

It was during this period that agglomerated stone-built townscapes like Molokwane, Kaditshwene, and Bokoni* proliferated across the northern highveld. These massive, sprawling towns incorporated a wide variety of architectural spaces, including semiprivate courtyards and living areas, cattle kraals and passages running through the center of local activity, public courts, and areas used for crafts.7

[ *On the stone ruins of Bokoni, please read: ‘Egalitarian systems and agricultural technology in pre-colonial South Africa.’ ]

On the northern Highveld, agglomerated towns like Molokwane, Marothodi, and Kaditshwene represented the late 18th-century capitals of Kwena, Tlokwa, and Hurutshe states. The largest of these is Molokwane, covering an estimated 5km2. John Campbell, who visited Kaditshwene (Kurreechane) in 1820, reported a population of 16,000 to 20,000, apparently more than that of Cape Town at the time. A similarly sized capital was Pitsane of the Baralong, located further north in Botswana, it was said to have about 20,0000 inhabitants according to Robert Moffat.8

Molokwane ruins.

Aerial view of the main settlement unit at Marothodi. image by J.C.A Boeyens.9

Aerial view of Kaditshwene Hill. image by Gernot Langwieder10

The layouts of these settlements demonstrated different attitudes toward the control of space and resources. Molokwane’s and Marothodi’s layouts emphasized the location of cattle in a central, communal area, while Kaditshwene’s cattle were more spatially segregated from communal life. Marothodi featured evidence of significant metalworking of copper and iron, some of which was likely exported to Molokwane, which yielded finds of worked metal but no evidence of metalworking.11

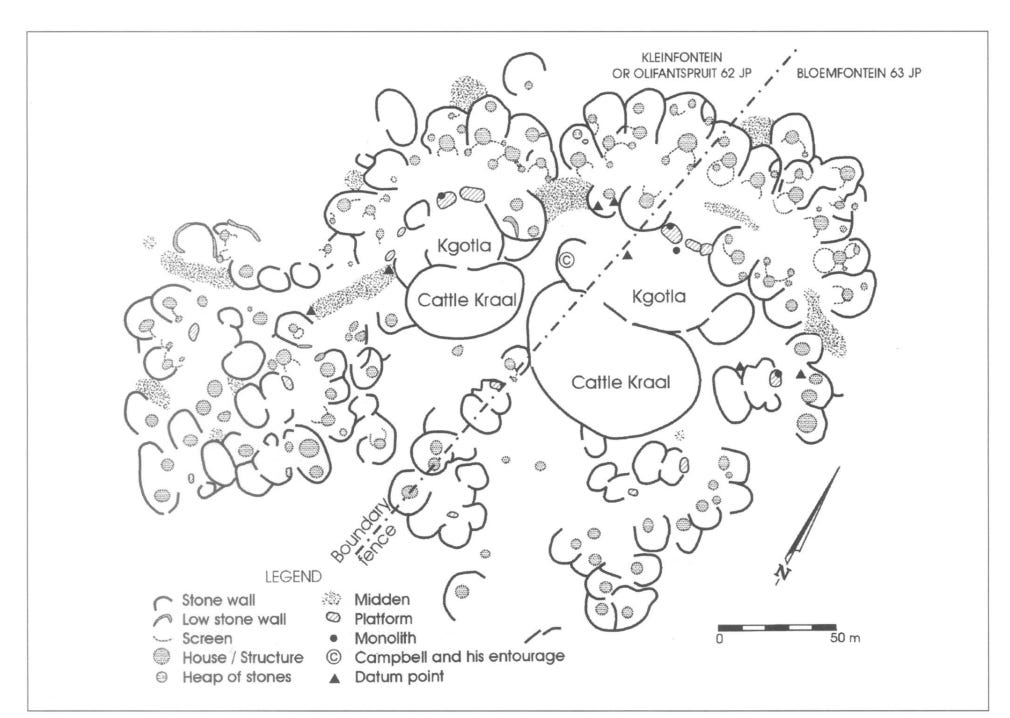

Site plan of the main ward (kgoro) in the kgosing of Kaditshwene. image by J.C.A Boeyens

The inhabitants of these capitals were ruled by sovereign kings (dikgosi). Their capitals contained wards administered by appointed headmen, these wards were comprised of several dwellings, a cattle pen, and a court (kgotla); the primary, formal forum where judicial, political, and administrative affairs were debated. These features of Tswana society, which are first mentioned in the early 19th century accounts by various visitors to the region, were better described in early 20th century accounts of Tswana communities in the region.12

Among the most distinctive features of the ruined capitals of the northern Highveld was the kgotla, next to this was the homestead of the chief and the central kraal complex. These were surrounded by a maze of wards and homesteads (kgoro) of the commoners, along with their kraals, all of which were bisected by stone walled lanes leading to different sections of the site which served various functions.13

Some pre-colonial Tswana capitals were divided into three geographical zones the kgosing in the centre (fa gare), and an upper (ntlha ya godimo or kwa godimo), and a lower division (ntlha ya tlase or kwa tlase) on either side. Each division consisted of a number of wards (dikgoro), comprising a number of lineages (masika). Besides wards of the royals (dikgosana), the kgosing in the center comprised wards of the kgosi's retainers . The inhabitants of the other two divisions consisted of persons not specially bound to the kgosi and included royals as well as commoners and immigrants.14

Ruins of Kaditshwene, image by J. C.A. Boeyens.

[On the history of Kaditshwene, please read: Revolution and Upheaval in pre-colonial Southern Africa. ]

The ruined stone towns of the central and southern Highveld

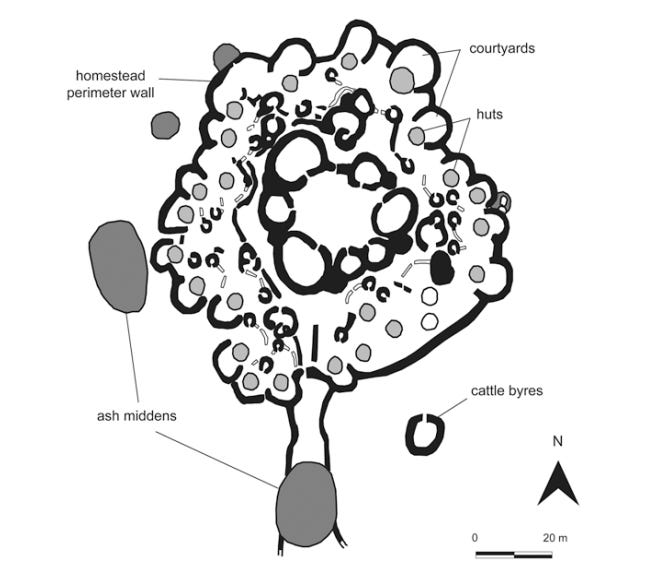

In this region of the Highveld, regional settlement proceeded at a more modest scale from the 15th century. While early architectural trends featured walling made of reeds, stone became the main building material from the 17th century at sites like Makgwareng and Kweneng. The typical household unit here featured a bilobial layout that linked three circular enclosures separating various domestic functions, and the material culture found within these units provided evidence for craft specialization and exchange.15

Plan of a Molokwane-type homestead on the Highveld showing ‘scalloped’ perimeter walls, cattle track, cattle byres, and placement of ash. Image by Rachel King

Outline of the ruins of a stone dwelling with a bilobial layout, at OXF 1; known as Matloang. image by Tim Maggs

Makgwareng represented one of a number of settlement layouts observable on the southern Highveld, many of which featured large perimeter walls encircling rondavels whose architectural compositions included elements like corbelling, paved courtyards, and multiple ‘lobes’ in a single dwelling. The archaeologist Tim Maggs has identified several other similar sites across the southern Highveld using aerial photographs taken in the 1960s, and categorized them into four settlement types; N, V, Z, and R. The ruins at Makgwareng belong to type V, whose most distinctive feature is the corbelled stone dwellings and is thus the most archeologically visible of the four settlement types.16

Stone-walled structures at Makgwareng, Free State, South Africa. Image by Tim Maggs

Excavations at the site of Makgwareng (known by its Sotho name of lekgwara —stony hill/the place of stones) revealed multiple episodes of building across various zones beginning in 1520-1660. Material culture recovered from the site included local pottery, faunal remains, copper and iron objects, and a few trade items such as glass beads. In its later occupation phase, the number of stock pens decreased as human habitation increased. Finds of valuable material left in situ indicate that the site was hurriedly abandoned around the early 19th century, possibly due to the conflict between Hlubi and the Tlokoa just 60km away.17

North of Makgwareng is the ruined capital of Kweneng, which is made up of three sectors of clustered districts, each comprising several clusters of compounds, the largest of which contained over forty houses. Within each compound, circular stone-walled enclosures demarcated spaces for various functions, and a few compounds contained stone towers of unknown function. Unlike many of its peers, few of the stone-walled enclosures at Kweneng served as stock pens, save for two large enclosures near the central sector. There are a number of narrow passageways lined with stone that were likely used as roads and cattle drives. The settlement was constructed in multiple phases and is dated to between the 15th and 18th centuries.18

Examples of architectural styles at Kweneng. A) Type N; B-C) Klipriviersberg style; D-G) Molokwane style; H) Group IV. image by Karim Sadr

Some examples of stone towers at Kweneng. Top row (A–C) shows images from Kweneng Central while the bottom row (D–F) is from Kweneng South. The middle image (E) in the bottom row shows the monumental tower: note the folded umbrella for scale, as well as the standing section of the tower. image and caption by Karim Sadr.19

According to the archaeologist Karim Sadr, Kweneng is considerably larger than the other known ancient Sotho-Tswana capitals in South Africa, such as Molokwane and Kaditshwene. While Kaditshwene measures 4.5 km long and 1 km wide, and Molokwane is about 2.7 km long and about 750 m wide, the portion of Kweneng surveyed by LiDAR is 10 km long and 2 km wide. However, as with Molokwane and Kaditshwene, it is not clear whether all of Kweneng was occupied concurrently or its three sectors represent three consecutive capitals, especially since Tswana capitals were often abandoned and rebuilt elsewhere.20

Not far from Kweneng are the ruined settlements called Boschoek and Sun Shadow. The sites are part of a cluster of stone-walled ruins built in the Molokwane style, featuring a scalloped perimeter wall, with a few openings into the residential zone which surrounded the central livestock pens. their ceramics belong to the Buispoort facies found in neighbouring sites and are associated with Tswana-speaking groups. The material remains found at both sites indicate that the settlements were abandoned relatively quickly.21

Other important sites include; Nstuanatsatsi, whose ruins are mentioned in the account of Arbusset and Dauma 1846 in the origin of the Sotho. The site features Type-N settlement patterns, which are the oldest building style, and Type-V patterns, which indicate continued occupation. Dated samples from the site yielded a range of 1330-1440 CE, making it the oldest settlement on the Highveld. Another site is OXF1, which is known by the Sotho name of Matloang. The ruins extend over an area of about 1.2 x 0.5 km and are comprised of densely concentrated units characteristic of Type-Z settlements, some with multi-lobial houses and a few cobbled roundavels similar to Makgwareng.22

Air photograph of part of the Nstuanatsatsi settlement showing Type N settlement units. Image by Tim Maggs.

Section of the type-Z site ruins at OXF 1; known as Matloang, with walling built of thin flat slabs. image by Tim Maggs

Sedentarism, Mobility, and Warfare: why the ruined towns of the Highveld were abandoned.

“Many an hour have I walked, pensively, among the scenes of desolation —casting my thoughts back to the period when these now ruined habitations teemed with life and revelry. Nothing now remained but dilapidated walls, heaps of stones, and rubbish, mingled with human skulls, which, to a contemplative mind, told their ghastly tale.”

Travelers in the early 19th century who encountered these towns often attributed their abandonment to the regional warfare of the so-called mfecane wars —a prolonged period of regional warfare in southern Africa. Robert Moffat’s account, which is quoted in the above paragraph, attributes the sack of some of these towns to the armies of the Ndebele king Mzilikazi.23

This interpretation has been partially corroborated by the archaeological research at some of the sites described above. While many of the accounts had certainly been exaggerated by the biases of these external observers, the conflicts of the period were evidently disruptive. Yet despite the devastation, several polities survived this upheaval and were encountered by the same authors, indicating that its effects were varied.24

Additionally, recent archaeological work on several sites across the plateau undermines this singular interpretation and has shown that the mobility of agro-pastoralist communities in this region was fairly commonplace well before the 19th century. This indicates that the abandonment of some of these capitals was unrelated to the mfecane, but was likely tied to more localized factors.25

At the site of Kweneng for example, only one of the sampled houses in one of the two tested compounds shows evidence of a violent end and hasty abandonment. The other eight sampled lobes in the two compounds showed no evidence of burnt and hastily abandoned houses. This indicates that Kweneng may have been largely abandoned before the arrival of the Ndebele armies in the region during the late 1820s.26

Despite the seemingly permanent nature of the settlements, residents of some of the towns migrated semi-regularly within the vicinity of the town and beyond. Their populations often fluctuated significantly after the installation of new rulers as the latter reorganized the capital in order to accommodate changing social relations. Oral traditions of the Hurutshe for example, identify the following as their capitals in chronological order; Tswenyane, Powe, Rabogadi, Mmutlagae, Mmakgame, Kaditshwene, and Mosega.27

These internal shifts are also mentioned in 19th-century accounts of the capitals. The town of Litakun/Litakoo/Lattakoo., which was the capital of the Batlaping polity, moved three times in 20 years, and its population fluctuated significantly. When Samuel Daniell visited the place in 1801, the population was estimated at between 10,000 and 15,000 inhabitants. However, William Burchell reported 5,000 inhabitants in 1812. 28This was a full decade before the Battle of Dithakong in 1823, which is considered part of the mfecane, which points to internal processes for this decline.

The stone settlements of the Highveld were the product of multiple internal and regional processes such as the centralization of political power by rulers the accumulation of cattle wealth, competition between chiefdoms, population growth, and ecological stress. While stone architecture may be relatively permanent, its production and maintenance were firmly located within peoples’ changing relationships with the surrounding landscape and resources.29

Both internal processes and regional upheaval influenced the settlement patterns of Sotho-Tswana capitals, as well as the abandonment and establishment of new towns. The ruined stone-towns of the Highveld are thus the cumulative legacy of social complexity in southern Africa, preserving fragments of its dynamic social, economic, and political history as it evolved from the end of the Middle Ages to the dawn of the colonial era.

View of Makgwareng, Free State, South Africa, from the northeast after excavation. Image by Timm Maggs.30

My latest Patreon article is about the gold standard of pre-colonial Asante in West Africa, whose economy and political hierarchy were strongly linked to the use of the precious metal as currency.

Please subscribe to read about it here:

Map by Karim Sadr, modified by author

A Journey to Lattakoo, in South Africa. Abridged from the Author [from His "Travels in South Africa"]. [With a Map.] by John Campbell

Missionary Labours and Scenes in Southern Africa By Robert Moffat pg 394

Outlaws, Anxiety, and Disorder in Southern Africa: Material Histories of the Maloti-Drakensberg by Rachel King pg 109-110

Missionary Labours and Scenes in Southern Africa By Robert Moffat pg 523-524

Outlaws, Anxiety, and Disorder in Southern Africa: Material Histories of the Maloti-Drakensberg by Rachel King pg 114, The Late Iron Age Sequence in the Marico and Early Tswana History by Jan C. A. Boeyens pg 75

Outlaws, Anxiety, and Disorder in Southern Africa: Material Histories of the Maloti-Drakensberg by Rachel King pg 115

The spatial patterns of Tswana stone-walled towns in perspective Gerald Steyn pg 110-118, 122, 101

The Entangled Past: Integrating Archaeology, Oral Tradition and History in the South African Interior by JCA Boeye

A tale of two Tswana towns: In quest of Tswenyane and the twin capital of the Hurutshe in the Marico by Jan C.A. Boeyens

Outlaws, Anxiety, and Disorder in Southern Africa: Material Histories of the Maloti-Drakensberg by Rachel King pg 123

Kweneng: A Newly Discovered Pre-Colonial Capital Near Johannesburg Karim Sadr pg 1-2

The spatial patterns of Tswana stone-walled towns in perspective by Gerald Steyn pg 115-118

The Late Iron Age Sequence in the Marico and Early Tswana History by Jan C. A. Boeyens pg 71

Iron Age Communities of the Southern Highveld by Tim Maggs pg 3-6, 130, 238-244)

Iron Age Patterns and Sotho history on the southern Highveld: South Africa by T Maggs pg 320-325 Iron Age Communities of the Southern Highveld by Tim Maggs pg 28-48

Iron Age Communities of the Southern Highveld by Tim Maggs pg 48, 129-137

Kweneng: A Newly Discovered Pre-Colonial Capital Near Johannesburg Karim Sadr pg 4-16

The stone towers of Kweneng in Gauteng Province by Karim Sadr

Kweneng how to lose a precolonial city by Karim Sadr

Diving into the collections: Analysing two excavated Sotho-Tswana compounds in the Suikerbosrand, Gauteng Province. By Christopher Hodgson and Karim Sadr

Iron Age Communities of the Southern Highveld by Tim Maggs pg 140-159, 230-235

Missionary Labours and Scenes in Southern Africa By Robert Moffat pg 345-348

Iron Age Communities of the Southern Highveld by Tim Maggs pg 310-311

Re-constructing Tswana Townscapes: Toward a Critical Historical Archaeology by Paul Lane, The Late Iron Age Sequence in the Marico and Early Tswana History by Jan C. A. Boeyens

Report on the test pit excavations at two stone-walled compounds in Kweneng North by Karim Sadr & Christopher Hodgson 9-10, Kweneng: A Newly Discovered Pre-Colonial Capital Near Johannesburg Karim Sadr pg 3)

The Late Iron Age Sequence in the Marico and Early Tswana History by Jan C. A. Boeyens pg 68-69

The spatial patterns of Tswana stone-walled towns in perspective by Gerald Steyn pg 105

The Late Iron Age Sequence in the Marico and Early Tswana History by Jan C. A. Boeyens pg 70-71, Outlaws, Anxiety, and Disorder in Southern Africa: Material Histories of the Maloti-Drakensberg by Rachel King pg 118-119

The Archaeology of Southern Africa By Peter Mitchell pg 369

First off thank you for another banger of an article.

So question, were these walls include the beehave homes eg Zulus, or were the living spaces stone dwellings as well, or were there were two distinct traditions, in the same regions involving distinct populations.