The ancient city of Meroe: the capital of Kush (ca. 950 BC-350 CE)

Journal of African cities: chapter 15

Located in the desert sands near the Nile in modern Sudan is the ancient city of Meroe, which ranks among the world's oldest cities and is home to iconic Nubian pyramids.

Established as early as the 10th century BC, Meroe was the political and cultural center of the great African Kingdom of Kush until its collapse in the 4th century of the common era. The powerful rulers who resided at Meroe constructed massive palaces, temples, and monuments, and their subjects transformed the city into a major religious and industrial center, once referred to as the 'Birmingham of Africa'.

This article outlines the history and monuments of the ancient city of Meroe, utilizing images from the first excavations which uncovered the buildings more than 1,500 years after the ancient capital was abandoned.

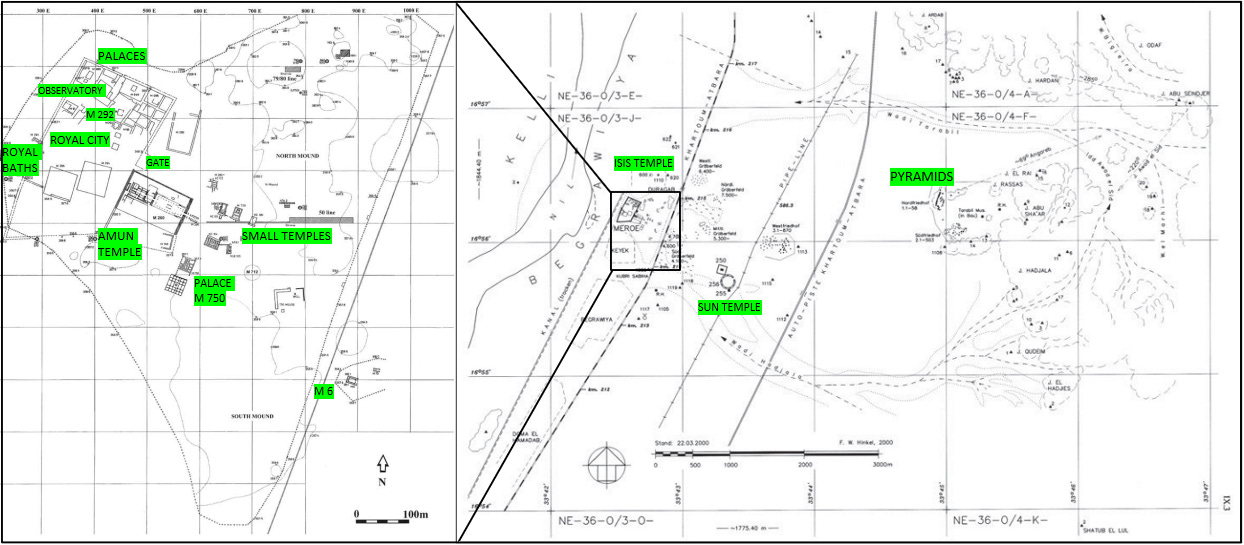

Map showing the location of Meroe.

Sudan’s heritage is currently threatened by the ongoing conflict. Please support Sudanese organizations working to alleviate the humanitarian crisis in the country by Donating to the ‘Khartoum Aid Kitchen’ gofundme page.

A brief background on the history of Meroe.

The city of Meroe first appears in the historical records on the inscription of King Amannote-erike who ruled Kush during the second half of the 5th century BC in the Napatan period (named after Kush’s old Royal city of Napata).

The inscription mentions that Amannote-erike was “among the royal kinsmen” when his predecessor King Talakhamani died “in his palace of Meroë”. The city later appears in the inscription of his sucessor King Harsiyotef in reference to an Osiris procession, and on the 4th century BC inscription of King Nastasen who writes: “When I was the good youth in Meroë, Amun of Napata, my good father, summoned me, saying, ‘Come!’. I had the royal kinsmen who were throughout Meroë summoned…He will be a king who dwells successfully in Meroë…” 1

Meroe also appears as the capital of the ‘Aithiopians’ in Herodotus' account from the 5th century BC. Based on information he received while in Egypt, Herodotus provides a semi-legendary account of the city, mentioning the fountain of youth whose “thin” water supposedly enabled the “long-lived” aithiopians (Meroites of Kush, not to be confused with modern Ethiopia) to live up to 120 years. Herodotus also refers to a prison where the prisoners were bound in fetters of gold because copper was deemed more valuable, and to a building outside the city called “Table of the Sun.” where animal offerings were left.2

Meroe was later visited by travelers from Ptolemaic Egypt such as Simonides the Younger and Philon who wrote a now-lost account of the city and the kingdom in the 3rd century BC. These provided some of the information in the later accounts of Alexandrian geographer Eratosthenes of Cyrene (c. 246-194 BC) and the ethnographer Agatharchides of Cnidus (b. 200 BC). It’s from the latter that we get a semi-legendary account of King Ergamenes (Arkamaniqo), who is credited with establishing a new dynasty (often referred to as the ‘Meroitic’ dynasty) after overthrowing the Napatan dynasty by shifting the royal cemetery from Napata to Meroe.3

The original name of Meroe was likely written as either Bedewi or Medewi, which is preserved in the name of the modern village of Begrawiya located next to the ancient site. In the texts of Kush’s Napatan-period, the name of Meroe is rendered Brwt, while in the Ptolemaic texts, it is rendered as Mirw3i and in demotic inscriptions as Mrwt. The Greeks rendered the name as Μερόη, which was transliterated as Meroe in Latin and modern languages.4

Description of the monuments of Meroe

The ancient city of Meroe is situated on the east bank of the Nile on a slightly elevated ground between two small seasonal rivers which branched out during the rainy season, making Meroe a seasonal island. The ruins of the ancient site cover an area of approximately 10km2, and include; the royal section enclosed by a wall; the north and south mounds which included domestic quarters; the outlying temples of Apedemak, Isis, the ‘Temple of the Sun’; and the three pyramid complexes east of the city.5

A panoramic photograph of Meroë created from images taken from the north of the enclosure wall of the Royal City at the end of the excavation in 1914. University of Liverpool.

Reconstruction of the city of Meroë, taken from Rebecca J Bradley.6

The site of Meroe was settled as early as the 7th millennium BC as indicated by finds of early pottery belonging to the ‘Khartoum Mesolithic’ tradition. Other materials dated to 1730–1410 BC, 1400–1000 BC, and 1270–940 BC indicate a continued albeit semi-permanent human activity in the area. The foundation levels of the oldest structures found at the site, such as the palace M 750S and building M 292, provide dates ranging from 1010–800 BC to 961–841 BC. The distance between these structures and their construction in the 10th-9th century BC, suggests that the early town of Meroe was already occupying a substantial area by then.7

Meroe came under the political orbit of the Napatan kingdom of Kush early in its history, although the exact nature of Kush's control remains a subject of debate8. Excavations at the Palace M 750S revealed an older building with a large quantity of the Early Napatan pottery. The West Cemetery at Meroe contained graves of high officials and relatives of the early Kushite kings from Piankhy to Taharqo, dating to 750–664. Epigraphic evidence from within the city goes back to the 7th-century Bc rulers Senkamanisken and Anlamani, whose names were inscribed on objects found near Palace M 294 within the Royal City.9

Napatan-era calcite vessel in the form of an oryx, bound for sacrifice, found at Meroe. Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

The Napatan royals likely resided in Meroe long before the city explicitly appears in the internal documents of the 5th-century BC mentioned above. This is indicated by the construction of a palace or temple dated to the 7th century BC in what would later become the royal compound; as well as King Aspelta’s construction of temple M 250 in the 6th century BC and the burial of a King’s wife in the Begrawiya South cemetery. The references to Meroe in the stela of Irike-Amanote, Harsiyotef, and Aspelta in the context of internal strife and war likely indicate that the control of the city (or its hinterland), was likely contested even before King Arkamaniqo ultimately overthrew the Napatan dynasty around 275BC and moved the King’s burial site to the Begrawiya South cemetery.10

The appearance of the first burial of a King at the South Cemetery of Meroe also coincided with the creation of a separate royal district enclosed within a monumental wall.

The masonry wall is about 5m thick, it originally stood several meters high and formed an irregular rectangle of 200x400m. Its construction is dated to between the early to mid 3rd century BC and encloses an area considered to be the “Royal City,” because of the numerous monumental buildings within it. It likely had no defensive function but rather served a monumental function separating the elite section of the city. The wall is pierced by five gates, whose asymmetrical location may reflect the position of the most important structures located in the city prior to its erection, and the course of the Nile channel.11

Aerial view of the Amun temple M 260 and and the enclosure wall, photo by B. Żurawski.

Meroe City, “Royal Enclosure”, west wall behind the late Amun temple. image by L. Torok.

The Amun Temple at Meroe, also known as M 260, is the second-largest Kushite temple after the Napatan temple B 500 at Jebel Barkal.

It consists of; a courtyard with 3.8 m tall pylons (now collapsed) and a Kiosk containing Meroitic inscriptions of King Natakamani and Queen Amanitore; a hypostyle forecourt that had a unique embedded stone basin and many Meroitic inscriptions eg the stela of Amanishaketo; and a Temple core with a series of hypostyle halls and side rooms, some with Meroitic inscriptions such as the stela of Amanikhabale, others with decorated and painted scenes with figures of royals and deities, and one with stone throne base measuring 1.93 x 1.8m .

The temple was constructed in two main phases, with the first phase completed in the 1st century BC, which is corroborated by the dating of the material found at the site, while the second phase saw the addition of other structures between the 1st and 3rd century CE by various rulers.12

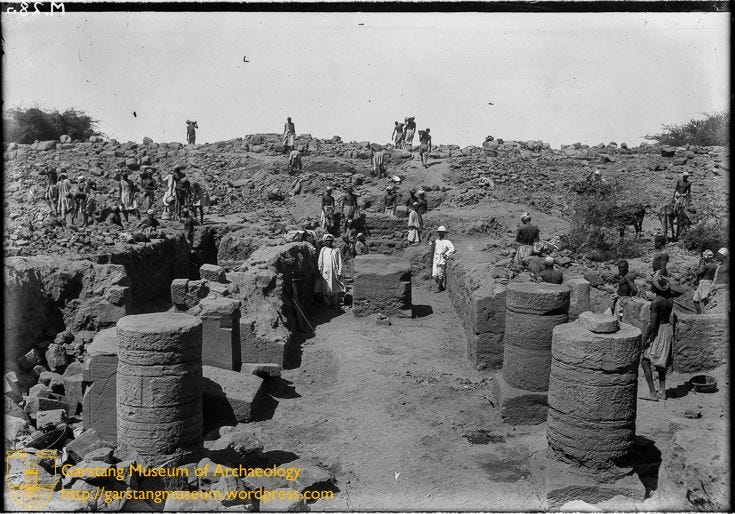

The Amun Temple (M260) after excavation, looking east from the enclosure wall across the centre of the temple. ca. 1912, University of Liverpool.

Temple of Amun M 260, Meroë Royal City, Flickr photo by TobeyTravels

The interior of the Amun temple at Meroë, looking west. The central sanctuary containing the high altar can be seen in the background. The enclosure wall of the royal city can be seen in the far background.

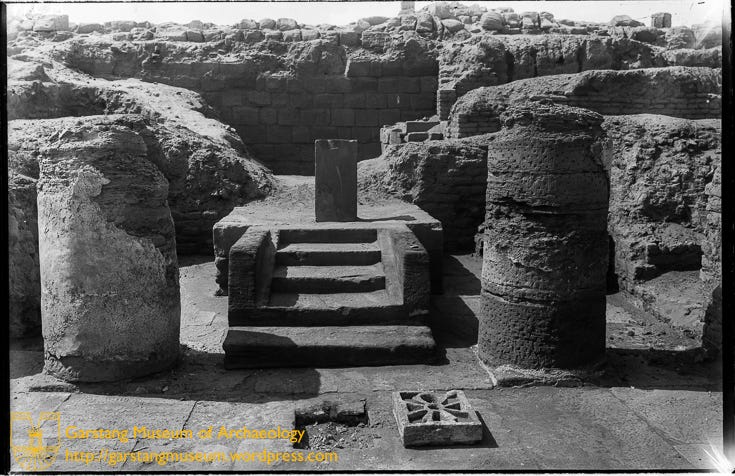

The main altar in the temple of Amun at Meroë, after clearing. The altar is decorated with images of the Egyptian Nile god Hapi.

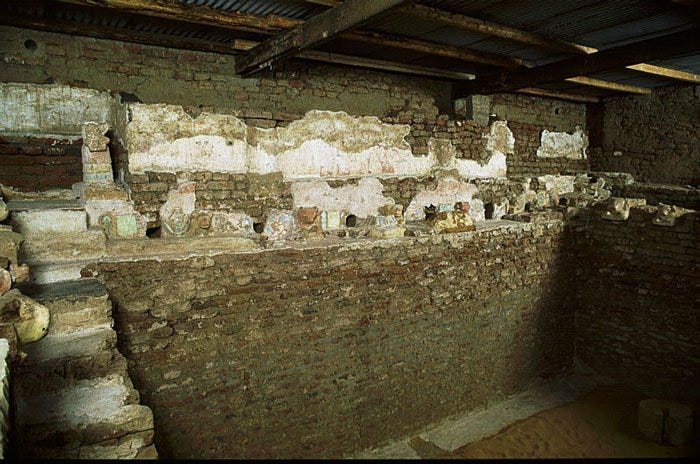

Remains of one of the hypostyle halls of the Amun temple in Meroë.

Stairs leading up to an altar at the Amun temple at Meroë. A small offering table can be seen in the foreground

Among the most unique buildings in the Royal compound is one of the oldest structures in the city called M 292. This was an important religious building, likely a chapel of a deity, that was continually rebuilt from the 10th century BC to the very end of the kingdom. It consists of two superimposed buildings, the lower one of whose columns (seen below) served as the bases for columns of a secondary structure. Its walls were extensively painted and decorated with victory scenes including Roman captives taken after Queen Amanirenas’ defeat of a Roman invasion, and it was here that the famous head of emperor Augustus was found.13

Section of building M 292 after excavation showing remains of a peristyle and columns. ca. 1911, University of Liverpool.

watercolor illustrations of captive paintings found in building 292 at Meroe, depicting bound Roman and Egyptian soldiers on the footstool of a Queen and a Meroitic deity. The originals on the right show the detail of the right footstool (top) and left footstool (bottom), and the larger painting of the left footstool. ca. 1911, University of Liverpool.

There are several monumental structures within the Royal compound identified as palaces, including, M 950, M 990, and M 998, dating to between the 2nd century BC and the 2nd century CE.14

Besides these is an old palace M 750, located outside the Royal city, south-east of the Amun temple. It consisted of two structures separated by a garden, and its interior contained inscribed and decorated blocks depicting procession scenes, as well as material dated to between the 8th century BC to 3rd century CE. Its construction method was similar to other Meroitic monuments: the stone foundations supported a plastered redbrick building covered with a brick roof resting on wood and palm fronds. Finds of pottery sherds lined on the west side of the palace indicate that some of the streets were paved to form a hard surface.15

Comparative floor plans and elevation of some of the Meroitic palaces at Muweis, Wad Ben Naqa, Napata and Meroë (M251-253). Illustrations by Marc Maillot16

Meroë palace M 750, ca. 1911, University of Liverpool.

Palace (M 750) ,Meroë Royal City, Flickr Photo by TobeyTravels.

An astronomical observatory, M 964, was found within, and below, Palace M 950. Its function was determined by the graffiti incised on the wall showing two individuals with a wheeled astronomical instrument observing the sky and making calculations that were then inscribed on the wall in cursive meroitic. Added to this was the square and triangular stone pillars in the entrance, graffiti of instruments on the walls, and the stone basin in the subterranean room 954 for measuring Nile water, all of which were used by local priests to time specific Meroitic festivals.

Image of graffiti on the wall of site 964, showing an astronomer using an instrument, and astronomical observations of equations written in cursive Meroitic. University of Liverpool.

Meroë site 964: 'observing' stones and steps to tank, Meroë site 954: 'Bath in observatory buildings'. University of Liverpool.

« Read more about the Meroe observatory here:

Another unique structure of the later period is the so-called Royal Bath complex, M 194-5 is a 30x70m structure from the 3rd century BC, located on the western edge of the Royal City between the Enclosure Wall and Palace M 295.

Its main feature is a brick-lined and plaster-covered pool 7.25 ×7.15 m and 2.50 m deep, surrounded by an ambulatory filled with locally made statuary, and supplied with water which flowed through water inlets cleverly concealed by the painted wall. A pipe fitted into a column stood in the center of the pool so that the water would flow into the basin from the spouts in the south wall and sprinkle fountain-like in the center. This fountain feature recalls Herodotus’s observation of the “fountain of youth” at Meroe, which secured the longevity of the Meroites, an interpretation that is further complemented by paintings associated with the cults of Dionysus and Apedemak, who are linked with re-birth, well-being, and fertility.17

Image of site 195 ('Royal Baths'), from the east, showing the tank and nearby chambers during excavation. Image of the excavation of the tank at site 195 ('Royal Baths'). ca. 1911, University of Liverpool

Image of site 194 ('Royal Baths') during excavation, showing what Garstang believed was a tepidarium, with seats decorated with griffins and various pieces of sculpture. University of Liverpool.

Detail of the interior of the tank in the Royal baths.

Image of an aqueduct or water channel discovered at site 194/195 'Royal Baths', south west corner of the tank discovered at site 195 ('Royal Baths'), with decorative carvings, sculptures and pipes. University of Liverpool.

statute of a reclining figure and a reclining couple discovered in the tank at site 195 ('Royal Baths'), 3rd century BC. Glyptothek Museum, University of Liverpool. On the right is a statue of Aphrodite, Münich ÄS 1334.

Palace M295 next to the ‘Royal baths’, showing an aqueduct and water tank. ca. 1911, University of Liverpool.

Most of the buildings excavated in the northeast part of the Royal City seem to be domestic quarters, magazines, and storage houses. East of the main Amun temple M260 were a series of small temples on both sides of a wide, open avenue that formed the processional way. These small, multi-roomed temples show quite a diversity of layouts: including a simple three-roomed edifice (M720), a building erected on a high podium (KC 101), and a double temple (KC 104).18

The formal Processional Way to the Amun Temple separated two domestic areas known as the North Mound and the South Mound. The North mound excavations revealed extensive domestic occupations, iron furnaces along with heaps of iron slag, pottery kilns, and a large temple dedicated to Isis. Excavations in the south Mound revealed other important buildings besides the palace M 750, these included domestic remains such as; M 712, which contained a bakery; and the structure at SM 100 whose material was dated to between the 8th and 4th century BC.19

To the east of the city is building M 6, identified as the 'Lion Temple' of the Meroitic god Apedemak. It consists of two small rooms within an enclosing stone wall which is decorated with reliefs. It contained statues of lions, an inscribed stela with the name of the Lion-headed deity Apedemak, and inscriptions belonging to the 3rd century CE Kings; Teqorideamani and Yesebokheamani.20

Remains of columns and a Lion statue at the temple M6 in Meroe, ca. 1911, University of Liverpool.

Inscribed stela and a wooden sundial in the shape of the ‘Sun Temple’ discovered at temple M6 (Lion Temple). ca. 1911, University of Liverpool.

Votive Plaque of a King Found in the lion temple at Meroë. Walters Art Museum.

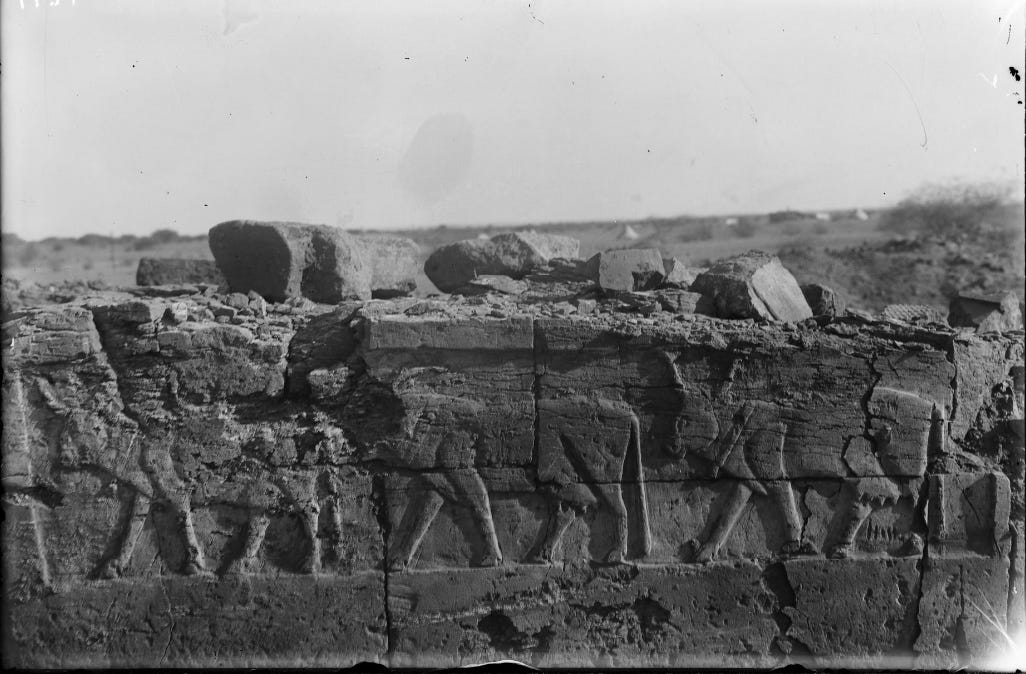

Further east of the ‘Lion Temple’ is building M 250, which is often wrongly called ‘Sun Temple’ after Herodotus’ fanciful account (there’s little evidence of sun worship at the temple). It was built in the 1st century BC by Prince Akinidad ontop of the remains of an earlier building erected by the Napatan King Aspelta. The edifice consists of a cella standing on a podium placed in the center of a peristyle court on top of a large artificial terrace approached by a ramp. It features highly decorated walls with relief registers depicting victory scenes.21

General view of building M250 from the northeast after excavation showing the temple entrance, ca. 1911, University of Liverpool.

center of the south front of the building M250. Victory scenes on the south side of site 250, University of Liverpool.

Reconstruction of building M 250.

Victory scenes on the south side of the lower podium of building M250, University of Liverpool.

To the north of the city is M 600, identified as the temple of Isis, which was later reused in the medieval period as a church. It consisted of two columned halls leading to a shrine, where the altar stood on a floor of faience tiles. It contains a stela of King Teriteqas, two large columnar statues of the gods Sebiumeker and Arensnuphis protecting its entrance, and two figures of the goddess Isis.22

chambers discovered at Meroe temple M600 (Isis Temple)., University of Liverpool.

statue of Sebiumeker and Arensnuphis, 1st century BC, discovered at temple M600 (Isis Temple), now at Carlsberg Glyptotek museum, National Museum of Scotland.

Life in the ancient city of Meroe

An estimated 9,000 inhabitants lived in the royal city, including members of the Royal family and ordinary people. The bulk of the latter population lived in the smaller houses of mud-brick walls found across the archeological site, and were engaged in a variety of crafts industries, from iron working, to gold smelting, textile manufacture, pottery making, the construction of monumental palaces, temples, and tombs found in the city, and the various sculptures and artworks that decorated their interior.

Section of building M 296 showing a complete ‘Taharqa’ style column and column bases, and a decorated doorway. ca. 1911, University of Liverpool.

Meroë site 98: Bath in a private house, Meroë site 621: Tank. ca. 1911, University of Liverpool.

According to Strabo’s description of Kush;

“They live on millet and barley, from which they also make a beverage. Butter and suet serve as their olive oil. Nor do they have fruit trees except for a few date palms in the royal gardens. . . . They make use of meat, blood, milk, and cheese. . . . Their greatest royal seat is Meroe, the city with the same name as the island”. He adds that the land was populated by nomads, hunters, and farmers and that the Meroites were mining copper, gold, iron, and precious minerals.23

Discoveries of massive slag heaps, kilns, and forges in the outskirts of Meroe and the neighboring town of Hamadab, along with the remains of iron and copper tools, and gold and bronze jewelry, attest to the city’s importance as an important center of local industries (the iron-slag mounds in particular earned it its nickname of the ‘Birmingham of Africa’). Commodities such as salt, gold, and other minerals, along with ebony, ivory, and other exotica were major trade items exported from Meroe to the Mediterranean world.24

Images of site 298, showing kiln-like structures that Garstang believed were coppersmith's hearths. University of Liverpool.

kilns discovered at site 620 after excavation. University of Liverpool.

Large iron slag mound at Meroe, Sudan. photo by Jane Humpris.

Napatan and Meroitic gold jewelry. (mostly at the Boston Museum)

Painted pottery from Meroe, ca. 1st century BC- 1st century CE , SMB Berlin & Louvre

Meroe is located within the monsoon rain belt region of Central Sudan in a savannah environment dotted with acacia trees, making it suitable for agro-pastoralism which was the basis of Kush's economy in antiquity. The cultivation of cereals like sorghum was sustained by seasonal rains and the construction of water storages known as Hafirs. Finds of cattle bones and other animals (sheep, goats, pigs) in archaeological contexts corroborate written accounts about the importance of herding in Meroe.25

Image of a wall relief depicting a procession of oxen found at site 70 (Ox shrine). University of Liverpool.

The end of Meroe

Meroe remained a powerful capital well into the middle of the third century when the kingdom had to face serious political and economic difficulties, including the decline of Roman Egypt, the appearance of nomadic groups called the Blemmyes and the ‘Noba’ in its northern and eastern margins, and the rise of the Aksumite empire in the northern highlands of Ethiopia.26

The last inscription among the known Meroitic rulers, Talakhideamani, was found within the Amun Temple complex as well as in the Meroitic chamber at Philae (in Roman Egypt) where his envoys also left an inscription that contained the king's name, and at the temple of Musawwarat. His reign in the late 3rd century indicates that the kingdom, its capital and its main temple were still flourishing just decades before the Kush was invaded by the Aksumite kingdom.27

Talakhideamani's inscription on the south side of M 276, Amun temple, photo by K. Grzymski

The royal city was sacked by the Aksumite armies in the early 4th century CE, evidenced by two Greek inscriptions found on the site, belonging to King Ousanas. They bear the typical Aksumite title of; "King of the Aksumites and Himyarites …" and they describe his capture of Kush's royal families, the erection of a throne and bronze statue, and the subjection of tribute on Kush. Ousanas’ campaign was later followed by his successor Ezana in 360 CE, who directed his armies against the Noba that were by then occupying much of Kush’s territory.28

Emperor Ousanas’ victory inscriptions at Meroe. Sudan national museum

The very end of habitation at Meroe City is represented by squatter occupation in the abandoned temples and by poor burials cut into the walls of deserted palatial buildings and in the inner rooms of the late Amun temple, as well as the complete disappearance of wheel-turned pottery. The Meroitic dynasty likely ended with Queen Amanipilade, buried in Beg. N. 25, although the kingdom itself continued in some form until around 420 CE when the royals of the first medieval Nubian kingdom established their royal necropolis at Ballana, formally marking the end of ancient Kush and its historic capital.29

Meroë (Bagrawiyah) Pyramids North Cemetery, Flickr Photo by Bruce Allardice.

Please support Sudanese organizations working to alleviate the humanitarian crisis in the country by Donating to the ‘Khartoum Aid Kitchen’ gofundme page.

Centuries before the rise of Aksum, the northern Horn of Africa was home to several complex societies referred to as the 'Pre-Aksumite' civilization.

Please subscribe to read about it here;

The Double Kingdom Under Taharqo: Studies in the History of Kush and Egypt, c. 690 – 664 BC by Jeremy W. Pope pg 12-13.

Herodotus in Nubia By László Török

The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization By László Török pg pg 72-73, Hellenizing Art in Ancient Nubia 300 B.C. - AD 250 and Its Egyptian Models: A Study in "Acculturation" by László Török, Laszlo Torok pg 13-19.

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 545

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 456, 549.

A number of images in this essay were taken from the WildfireGames Forum article by ‘Sundiata’ titled: The Kingdom of Kush: A proper introduction [Illustrated].

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 551-552

‘Meroë as a Problem of Twenty-Fifth Dynasty History’ in The Double Kingdom Under Taharqo: Studies in the History of Kush and Egypt, c. 690 – 664 BC by Jeremy W. Pope.

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 551-552, Meroe, the capital of Kush, old problems and new discoveries, by Krzysztof Grzymski pg 56-58

The Double Kingdom Under Taharqo: Studies in the History of Kush and Egypt, c. 690 – 664 BC by Jeremy W. Pope pg 31-33

The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization By László Török pg 516-517.

The Amun Temple at Meroe Revisited by Krzysztof Grzymski pg 142

Meroe: A Civilization of the Sudan by P. L. Shinnie pg 78-79, The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 553

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 554)

Meroe, the capital of Kush, old problems and new discoveries, by Krzysztof Grzymski pg 52-54, The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 556.

The Meroitic Palace and Royal City by Marc Maillot

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 554, Hellenizing Art in Ancient Nubia 300 B.C. - AD 250 and Its Egyptian Models: A Study in "Acculturation" by László Török pg 139-188.

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 556)

Meroe, the capital of Kush, old problems and new discoveries, by Krzysztof Grzymski pg 47-51, The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 557

Meroe: A Civilization of the Sudan by P. L. Shinnie pg 83-84, The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization By László Török pg 477-479

The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization By László Török 367-270, 458, 520)

Meroe: A Civilization of the Sudan by P. L. Shinnie pg 84.

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 547, 557

Meroe: A Civilization of the Sudan by P. L. Shinnie pg 160-165, The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 547

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 456, 557)

The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization By László Török pg 476-478.

‘Appendix: New Light on the Royal Lineage in the Last Decades of the Meroitic Kingdom’ in : The Amun Temple at Meroe Revisited by Krzysztof Grzymski pg 144-146

Aksum and nubia by G. Hatke pg 67-80, 95-121, 135.

The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization By László Török pg 481-484

Always interesting to read your histories.