The currencies and monetary systems of pre-colonial Africa

A bewildering variety of currencies circulated freely in the various states and societies of Africa during the pre-colonial period.

In his description of commercial life in 19th-century Timbuktu, the German traveler Heinrich Barth gives us a fascinating insight into the complexity of currency exchanges involving gold dust, cowries, cloth, and salt bars, which were all used as currencies in the city’s markets.

He mentions that a slab of salt, about 3.5ft long, was exchanged for between 3,000 to 6,000 cowrie shells depending on the season, while large quantities above 9 slabs were exchanged for six turkedi (dyed tunics manufactured in Kano, Nigeria), and 8 slabs could fetch six mithqāl of gold depending on the distance.1

Among the land documents of late 18th century Ethiopia are records of several transactions made by a noblewoman named Sanayt from Bagemder, who sold and bought land on multiple occasions. Among some of the three land purchases she made; two were measured in gold ounces, and one of them was measured in salt bars and the Thaler —silver coins of Queen Maria Theresa I of Austria. The manuscripts show that the exchange rates between these currencies were often measured against the Thaler.2

A similar situation prevailed in the kingdom of Kongo during the early 17th century, where the predominant currencies were nzimbu cowry-shells and luxury textiles, whose values were measured against each other and the Portuguese reis. The most expensive dyed cloth was valued at 640 reis a piece in eastern Kongo but most of it was bought with cowries, with 1,000 of these shells being exchanged for 16—20 Portuguese reis in Mbanza Kongo.3

‘Gold merchants' in Timbuktu, Mali, ca. 1896

12th-century painting of a financial transaction between two men, with one giving the other a handful of gold coins. Old Dongola, Sudan.

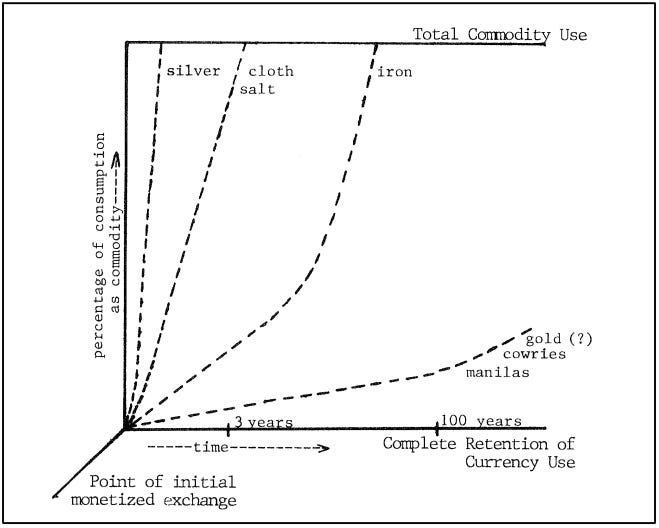

In most parts of the continent, trade in regional markets and other local transactions were mediated through many forms of money, including “classical” currencies such as coins, and commodity currencies like cowries, gold-dust, cloth, and salt which were standardized, could be stored, and were in high demand. Many of these types of exchanges were characterized by a variable rate of transactional money use and a degree of flexibility in currency substitution.4

The production of such monies and the management of what we would now refer to as “exchange rates” between the different currency systems was restrained by discretionary political considerations and was generally localized to particular frontiers at the interface of different economic and value systems.

For example, traders used a measured weight of gold dust called the mithqāl in the northern parts of western Africa, along with specific units of cowry shells and lengths of cloth, whose use extended into the forest regions and along the Atlantic coast, where all three currencies were used alongside other monies eg silver coins and manilla.5

Continuum of consumption of money in West Africa before 1800. image by James L.A. Webb

Changing value ratios of gold, silver, and cowries in the ‘western Soudan’. image by Philip Curtin

African states could, with varying degrees of success, control the circulation and use of currencies by imposing the payment of taxes in a specific currency, restricting the amount of currency in circulation using state treasuries, fixing prices of certain items, or issuing their own coinage.6

Examples of African societies that minted their own coins include the Aksumite empire at Aksum (Ethiopia), the Mahdiyya at Omdurman (Sudan), at least seven East African cities (Shanga, Pemba, Zanzibar, Kilwa, Mogadishu, Mombasa, Lamu)7, and the cities of Harar (Ethiopia), Nikki (Benin), Arawan (Mali),8 Tadmekka (Mali) and the medieval empire of Kanem (Chad).9

Gold coin of King Ebana of Aksum, found in Yemen, ca. 450-500. British Museum.

Gold coins from Kilwa Kisiwani, 14th century, Tanzania. image by Helen Brown.

Silver coins from Essouk-Tadmekka, Mali. image by Sam Nixon.

Gold Mahdi coin, late 19th century, Sudan. British Museum

In most of the societies where coins were minted (or circulated), the currencies were part of a complex monetary system characterized by the simultaneous circulation and acceptance of multiple currencies, including foreign coins —as was the case for most economies across the old world— and local commodity currencies.

Coins minted at Aksum, Harar, the Swahili coast, and Tadmekka were used alongside foreign coins from the Roman and Islamic world, with both local and foreign coins often found in the same hoards.

collection of gold jewelry, including 14 Roman coins of the Antonine era, crosses, and three chains. ca. 6th-7th century CE. late Aksumite period. Matara, Eritrea. image by Kebbedé Bogalé.10

The Mtambwe Mkuu hoard of silver coins, Pemba Island, Tanzania. image by Stephanie Wynne-Jones.11 Most of these coins were minted in Kilwa while others were from Fatimid Egypt.

The silver coins minted in Mombasa and Lamu during the 18th and 19th centuries were pegged to a fixed measure of grain and were used alongside the thaler which was also used as a unit of account.12

Additionally, in Ethiopia, Bornu, Sokoto, and the Senegambia region where thalers circulated, the silver coins were later melted down to make jewelry and other silver objects, further blurring the divide between so-called classical and commodity currencies.13

silver jewelry with rosette-shaped bezels and red stones. late 19th-early 20th century, Harar, Ethiopia. Quai Branly.

Most states therefore chose not to impose a uniform pattern of currency use over an extended period, preferring instead, a more flexible monetary system for their economies, which left traders with a free hand. The maintenance of a single type of currency for a wide range of transactions is thus only attested in a handful of pre-colonial African societies and was relatively uncommon in world history, hence the need for ‘money changers’ in many cities.

Among the most notable exceptions was the west African kingdom of Asante in modern Ghana whose rulers created a monetary system based on gold-dust. Located in one of the richest gold-producing regions in the world, the economy of pre-colonial Asante and its political hierarchy were strongly linked to the precious metal.

The circulation of gold was centrally controlled by the treasury in Kumasi, where a great chest holding about 400,000 oz of gold valued at £1.44 million in 1875 ( £156m today) was kept in the palace complex. The mining of gold was strictly regulated, the values of transactions and loans were all based on a fixed measure of gold called the peredwan, and most wealth was stored in gold-dust. Some of the wealthiest residents of Kumasi left treasures containing over 45,000 oz of gold-dust valued at £176,000 in 1824 ( £24.6 m today).14

The gold standard of pre-colonial Asante and the kingdom's monetary system are the subject of my latest Patreon article:

Please subscribe to read about it here:

Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa: Being a Journal of an Expedition Undertaken Under the Auspices of H. B. M.'s Government, in the Years 1849-1855, Volume 3 By Heinrich Barth, pg 361-2

Land and Society in the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia: From the Thirteenth to the Twentieth Century by Donald Crummey pg 195, 179.

The Mbundu and Neighbouring Peoples of Central Angola under the Influence of Portuguese Trade and Conquest by D Birmingham pg 146-147, The Kingdom of Kongo by Anne Hilton pg 106

Toward the Comparative Study of Money: A Reconsideration of West African Currencies and Neoclassical Monetary Concepts by James L. A. Webb, Jr pg 459

Credit, Currencies, and Culture: African Financial Institutions in Historical Perspective by Endre Stiansen, Jane I. Guyer pg 45-47

Credit, Currencies, and Culture: African Financial Institutions in Historical Perspective by Endre Stiansen, Jane I. Guyer pg 36-38, 85-86, 96)

The Swahili World edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria Jean LaViolette pg 448-450)

Credit, Currencies, and Culture: African Financial Institutions in Historical Perspective by Endre Stiansen, Jane I. Guyer pg 92-93)

Essouk - Tadmekka: An Early Islamic Trans-Saharan Market Town by Sam Nixon, pg 207

Matara: the Archaeological Investigation of a City of Ancient Eritrea by Francis Anfray

A Material Culture: Consumption and Materiality on the Coast of Precolonial East Africa by Stephanie Wynne-Jones

The Swahili World edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria Jean LaViolette pg 453-455

A Social History of Ethiopia by R. Pankhurst pg 235-238, Credit, Currencies, and Culture: African Financial Institutions in Historical Perspective by Endre Stiansen, Jane I. Guyer pg 46, 58, 66, Africa and the wider monetary world, 1250-1850 by Philip. D. Curtin in ‘Precious Metals in the Later Medieval and Early Modern Worlds by J. F. Richards, John F. Richards’

State and Society in pre-colonial Asante by T. C. McCaskie pg 62-64

This reminded me of my reading last year in a history of Colonial America, when the Iroquois Confederation established regular access to trade goods from the new colonists one this increased the availability of small glass beads that were included in the wampum the tribe made. This increased availability to the beads and related goods led to the manufacture of an increased amount of wealth - in effect the Iroquois 'printed more currency' - with expected effect of generating inflation as the native American economy responded.

Asante Professor.