The empire of Kong (ca. 1710-1915): a cultural legacy of medieval Mali.

At the close of the 18th century, the West African hosts of the Scottish traveler Mungo Park informed him of a range of mountains situated in "a large and powerful kingdom called Kong".

These legendary mountains of Kong subsequently appeared on maps of Africa and became the subject of all kinds of fanciful stories that wouldn't be disproved until a century later when another traveler reached Kong, only to find bustling cities instead of snow-covered ranges1. The mythical land of Kong would later be relocated to Indonesia for the setting of the story of the famous fictional character King Kong2.

The history of the real kingdom of Kong is no less fascinating than the story of its legendary mountains. For most of the 18th and 19th centuries, the city of Kong was the capital of a vast inland empire populated by the cultural heirs of medieval Mali, who introduced a unique architectural and scholarly tradition in the regions between modern Cote D'Ivoire and Burkina Faso.

This article explores the history of the Kong empire, focusing on the social groups that contributed to its distinctive cultural heritage.

approximate extent of the ‘Kong empire’ in 1740.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The early history of Kong and Dyula expansion from medieval Mali.

The region around Kong was at the crossroads of long-distance routes established by the Dyula/Juula traders who were part of the Wangara commercial diaspora associated with medieval Mali during the late Middle Ages. These trade routes, which connected the old city of Jenne and Begho to later cities like Kong, Bobo-Dioulasso, and Bonduku, were conduits for lucrative commerce in gold, textiles, salt, and kola for societies between the river basins of the Niger and the Volta (see map above).3

The hinterland of Kong was predominantly settled by speakers of the Senufu languages who likely established a small kingdom centered on what would later become the town of Kong. According to later accounts, there were several small Senufu polities in the region extending from Kong to Korhogo in the west, and northward to Bobo-Dioulasso, between the Bandama and Volta rivers. These polities interacted closely, and some, such as the chiefdom of Korohogo, would continue to flourish despite the profound cultural changes of the later periods.4

These non-Muslim agriculturalists welcomed the Mande-speaking Dyula traders primarily because of the latter's access to external trade items like textiles (mostly used as burial shrouds) and acculturated the Dyula as ritual specialists (Muslim teachers) who made protective amulets. It was in this context that the city of Kong emerged as a large cosmopolitan center attracting warrior groups such as the Mande-speaking Sonongui, and diverse groups of craftsmen including the Hausa, who joined the pre-existing Senufu and Dyula population.5

Throughout the 16th century, the growing influence of external trade and internal competition between different social groups among the warrior classes greatly shaped political developments in Kong. By 1710, a wealthy Sonongui merchant named Seku Umar who bore the Mande patronymic of "Watara" took power in Kong with support from the Dyula, and would reign until 1744. Seku Umar Watara’s new state came to be known as Kpon or K'pon in internal accounts, which would later be rendered as “Kong” in Western literature. After pacifying the hinterland of Kong, Seku's forces campaigned along the route to Bobo-Dioulassao, whose local Dyula merchants welcomed his rule.6

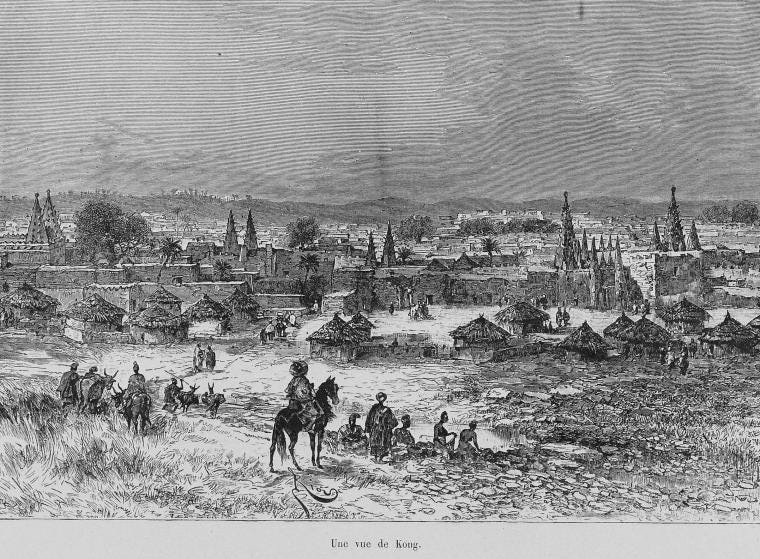

view of Kong, ca. 1892, by Louis Binger.

a section of Kong, ca. 1889, Binger & Molteni.

Palace of the Senufu king Gbon Coulibaly at Korhogo, ca. 1920, Quia Branly. Despite the Dyula presence in Korhogo and the town’s proximity to Kong, it was outside the latter’s direct control.

The states of Kong during the 18th century and the houses of Watara.

Seku Watara expanded his power rapidly across the region, thanks to his powerful army made up of local allies serving under Sonongui officers. Seku Watara and his commanders, such as his brother Famagan, his son Kere-Moi, and his general Bamba, conquered the regions between the Bandama and Volta rivers (northern Cote d’Ivoire) in the south, to Minyaka and Macina (southern Mali) in the north. They even got as far as the hinterland of Jenne in November 1739 according to a local chronicle. Sections of the army under Seku Umar and Kere Moi then campaigned west to the Bambara capital of Segu and the region of Sikasso (also in southern Mali), before retiring to Kong while Famagan settled near Bobo.7

The expansion of the Kong empire was partly driven by the need to protect trade routes, but no centralized administration was installed in conquered territories despite Famagan and Kere Moi recognizing Seku Umar as the head of the state. After the deaths of Seku (1744) and Famagan (1749) the breach between the two collateral branches issuing from each royal house grew deeper, resulting in the formation of semi-autonomous kingdoms primarily at Kong and Bobo-Dioulasso (originally known as Sya), but also in many smaller towns like Nzan, all of which had rulers with the title of Fagama.8

The empire of Kong, which is more accurately referred to as “the states of Kong”, consisted of a collection of polities centered in walled capitals that were ruled by dynastic ‘war houses’ which had overlapping zones of influence. These houses consisted of their Fagama's kin and dependents, who controlled a labyrinthine patchwork of allied settlements and towns from whom they received tribute and men for their armies.9 The heads of different houses at times recognized a paramount ruler, but remained mostly independent, each conducting their campaigns and preserving their own dynastic histories.10

In this complex social mosaic, many elites adopted the Watara patronymic through descent, alliance, or dependency, and there were thus numerous “Watara houses” scattered across the entire region between the northern Ivory Coast, southern Mali, and western Burkina Faso. At least four houses in the core regions of Kong claimed descent from Seku Umar; there were several houses in the Mouhoun plateau (western Burkina Faso) that claimed descent from both Famagan and Kere Moi. Other houses were located in the region of Bobo-Dioulasso, in Tiefo near the North-western border of Ghana, and as far east as the old town of Loropeni in southern Burkina Faso.11

Friday Mosque of Kong, ca. 1920, Quai Branly. The mosque was built in the late 18th century.

Street scene in the Marabassou quarter of Kong, ca. 1892, ANOM.

Bobo Dioulasso’s Friday Mosque, ca. 1904, Quai Branly. The mosque was built in the late 19th century.

section of Bobo-Dioulasso, ca. 1904, Quai Branly.

The influence of Dyula on architecture and scholarship in the states of Kong.

The dispersed Watara houses often competed for political and commercial influence, relying on external mediators such as the Dyula traders to negotiate alliances12. Although nominally Muslim, the Watara elites stood in contrast to the Dyula, as the former were known to have retained many pre-Islamic practices. They nevertheless acknowledged the importance of Dyula clerics as providers of protective amulets, integrated them into the kingdom's administration, and invited them to construct mosques and schools.13

The cities of Kong and Bobo became major centers of scholarship whose influence extended as far as the upper Volta to the Mande heartlands in the upper Niger region. The movement of students and teachers between towns created a scholarship 'network' that corresponded in large part to their trading network.14

Influential Dyula lineages such as the Saganogo (or Saganugu) acquired a far-ranging reputation for scholarship by the late 18th century. They introduced the distinctive style of architecture found in the region15, and are credited with constructing the main mosque at Kong in 1785, as well as in cities not under direct Watara control such as at Buna in 1795, at Bonduku in 1797, and at Wa in 1801. Their members were imams of Kong, Bobo-Dioulasso, and many surrounding towns. The Dyula shunned warfare and lived in urban settlements away from the warrior elite’s capitals, but provided horses, textiles, and amulets to the latter in exchange for protecting trade routes.16

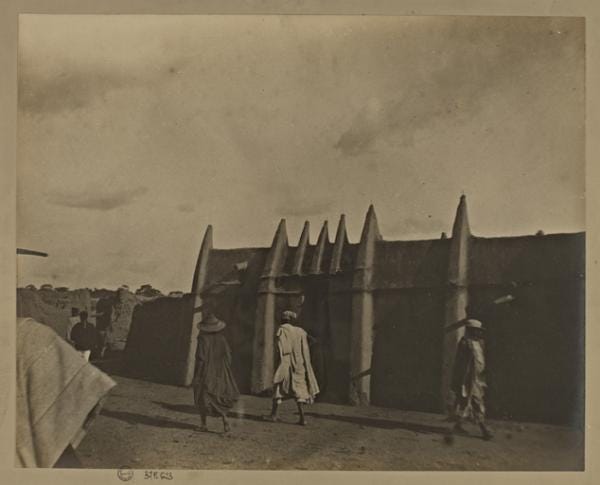

mosque in Kong, by Louis Binger, ca. 1892.

The Saganogo scholars of Kong (also known as karamokos : men of knowledge) are among the most renowned figures in the region’s intellectual history, being part of a chain of learning that extends back to the famous 15th-century scholar al-Hajj Salim Suware of medieval Mali.17

The most prominent of these was Mustafa Saganogo (d. 1776) and his son Abbas b. Muhammad al-Mustafa (d. 1801), who appear in the autobiographies of virtually all the region’s scholars18. The former promoted historical writing, and, in 1765, built a mosque bearing his name, which attracted many students. His son became the imam of Kong and, according to later accounts, "brought his brothers to stay there, and then the 'ulama gathered around him to learn from him, and the news spread to other places, and the people of Bonduku and Wala came to him, and the people of the land of Ghayagha and also Banda came to study with him."19

Descendants of Mustafa Saganogo, who included Seydou and Ibrahim Saganogo, were invited to Bobo-Dioulasso by its Watara rulers to serve as advisors. They arrived in 1764 and established themselves in the oldest quarters of the city where they constructed mosques, of which they were the first imams. Around 1840, a section of scholars from Bobo-Dioulasso led by Bassaraba Saganogo, the grandson of the abovementioned brothers, established another town 15 km south at Darsalamy (Dār as-Salām).20

The Saganogo teachers were also associated with several well-connected merchant-scholars with the patronymic of Watara who gained prominence across the region, between the cities of Kong, Bonduku, and Buna.21

Among these were the gold-trading family of five brothers, including; Karamo Sa Watara, who was the eldest of the brothers and did business in the Hausaland and Bornu; Abd aI-Rahman, who was married to the daughter of Soma Ali Watara of Nzan; Idris, who lived at Ja in Massina; Mahmud who lived in Buna and was married to a local ruler. Karamo's son, Abu Bakr al-Siddiq, who provided a record of his family’s activities, later became a prominent scholar in Buna where he studied with his cousin Kotoko Watara who later became ruler of Nzan. The head of the Buna school was Abdallah b. al-Hajj Muhammad Watara, himself a student of Mustafa Saganogo. Buna was a renowned center of learning attracting students from as far as Futa Jallon (in modern Guinea), and the explorer Heinrich Barth heard of it as "a place of great celebrity for its learning and its schools."22

An important marabout (teacher/scholar) in Kong, ca. 1920, Quai Branly. Neighborhood mosque in Kong, ca. 1892, ANOM.

The states of Kong during the 19th century

In the later period, the Dyula scholars would come to play an even more central political role in both Kong and Bobo, at the expense of the warrior elites.

When the traveler Louis Binger visited Kong in 1888, he noted that the ‘king’ of the city was Soukoulou Mori, but that real power lay with Karamoko Oule, a prominent merchant-scholar, as well as the imam Mustafa Saganogo, who he likened to a minister of public education because he managed many schools. He estimated the city’s population at around 15,000, and referred to its inhabitants’ religious tolerance —characteristic of the Dyula— especially highlighting their "instinctive horror of war, which they consider dishonorable unless in defense of their territorial integrity." He described how merchant scholars proselytized by forming alliances with local rulers after which they'd open schools and invite students to study.23

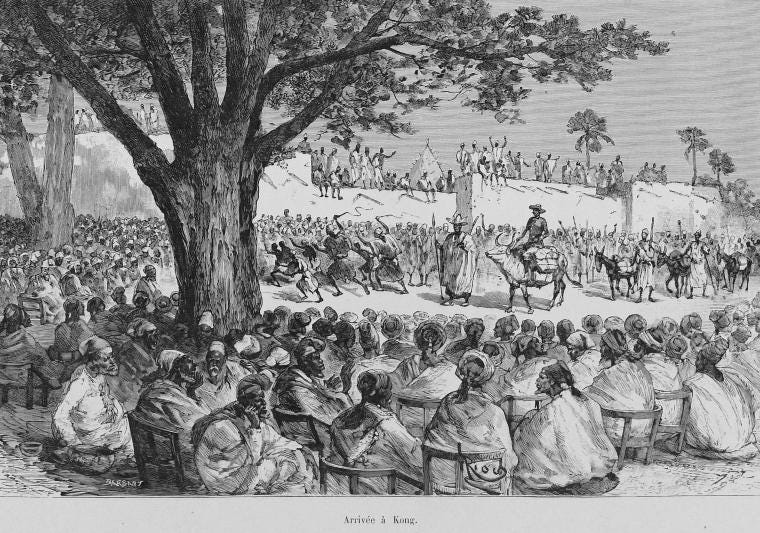

Arrival in Kong by Louis-Gustave Binger, ca. 1892

copy of the safe conduct issued to Binger by the notables of Kong, ca. 1892, British Library.

The main Watara houses largely kept to themselves, but would occasionally form alliances which later broke up during periods of extended conflict. The most dramatic instance of the shattering of old alliances occurred in the last decade of the 19th century when the expansion of Samori Ture’s empire coincided with the advance of the French colonial forces.24 Samori Ture reached this region in 1885 and was initially welcomed by the Dyula of Kong who also sent letters to their peers in Buna and Bonduku, informing them that Samori didn't wish to attack them. However, relations between the Dyula and Samori later deteriorated and he sacked Buna in late 1896.25

In May of 1897, the armies of Samori marched against Kong, which he suspected of entering into collusion with his enemy; Babemba of Sikasso, by supplying the latter with horses and trade goods. Samori sacked Kong and pursued its rulers upto Bobo, with many of Kong's inhabitants fleeing to the town of Kotedugu whose Watara ruler was Pentyeba.

Hoping to stall Samori's advance, Pentyeba allied with the French, who then seized Bobo from one of Samori's garrisons. They later occupied Kong in 1898, and after briefly restoring the Watara rulers, they ultimately abolished the kingdom by 1915, marking the end of its history.26

The historical legacy of Kong is preserved in the distinctive architectural style and intellectual traditions of modern Burkina Faso and Cote d'Ivoire, whose diverse communities of Watara elites and Dyula merchants represent the southernmost cultural expansion of Medieval Mali.

Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso.

The kingdom of Bamum created West Africa’s largest corpus of Graphics Art during the early 20th century, which included detailed maps of the kingdom and capital, drawings of historical events and fables, images of the kingdom's architecture, and illustrations depicting artisans, royals, and daily life in the kingdom.

Please subscribe to read about the Art of Bamum in this article where I explore more than 30 drawings preserved in various museums and private collections.

'From the Best Authorities': The Mountains of Kong in the Cartography of West Africa by Thomas J. Bassett, Philip W. Porter

The character's creator read many European travel accounts of Africa, traveled to the region around Gabon, was fascinated with African wildlife, and drew on 19th-century Western images of Africa and colonial-era films set in Belgian Congo to create the character. Biographers suggest that the name 'Kong' may have been derived from the kingdom of Kongo, although it is more likely that the legendary mountains of Kong which were arguably better known, and were said to have snow-covered peaks, forested slopes, and gold-rich valleys, provide a better allegory for King Kong's 'skull island' than the low lying coastal kingdom of Kongo.

Rural and Urban Islam in West Africa by Nehemia Levtzion, Humphrey J. Fisher pg 98-99, Islam on both Sides: Religion and Locality in Western Burkina Faso by Katja Werthmann pg 129)

Les états de Kong (Côte d'Ivoire) By Louis Tauxier, Edmond Bernus pg 23-27)

Rural and Urban Islam in West Africa by Nehemia Levtzion, Humphrey J. Fisher pg 104-106, The War Houses of the Watara in West Africa by Mahir Şaul pg 545)

Les états de Kong (Côte d'Ivoire) By Louis Tauxier, Edmond Bernus pg22, 39-41)

Unesco general history of Africa vol 5 pg 358, The War Houses of the Watara in West Africa by Mahir Şaul pg 549-551)

The War Houses of the Watara in West Africa by Mahir Şaul pg 550-551

The War Houses of the Watara in West Africa by Mahir Şaul pg 557-561, 566)

Les états de Kong (Côte d'Ivoire) By Louis Tauxier, Edmond Bernus pg 64-69)

The War Houses of the Watara in West Africa by Mahir Şaul pg 562-564)

The War Houses of the Watara in West Africa by Mahir Şaul pg 565)

Rural and Urban Islam in West Africa by Nehemia Levtzion, Humphrey J. Fisher pg 106-8)

Arabic Literature of Africa: The writings of Western Sudanic Africa, Volume 4; by John O.. Hunwick pg 539-541

Architecture, Islam, and Identity in West Africa: Lessons from Larabanga By Michelle Apotsos pg 75-78

Rural and Urban Islam in West Africa by Nehemia Levtzion, Humphrey J. Fisher pg 109-115, The History of Islam in Africa edited by Nehemia Levtzion, Randall L. Pouwels pg 101)

Arabic Literature of Africa: The writings of Western Sudanic Africa, Volume 4; by John O.. Hunwick pg 550-551.

Wa and the Wala: Islam and Polity in Northwestern Ghana by Ivor Wilks pg 97-100.

The History of Islam in Africa edited by Nehemia Levtzion, Randall L. Pouwels pg 102)

Islam on both Sides: Religion and Locality in Western Burkina Faso by Katja Werthmann pg 128-136

Arabic Literature of Africa: The writings of Western Sudanic Africa, Volume 4; by John O.. Hunwick pg 570-571

The History of Islam in Africa edited by Nehemia Levtzion, Randall L. Pouwels pg 103-104)

Literacy in Traditional Societies edited by Jack Goody pg 190-193, The History of Islam in Africa edited by Nehemia Levtzion, Randall L. Pouwels pg 107)

The War Houses of the Watara in West Africa by Mahir Şaul pg 564)

The History of Islam in Africa edited by Nehemia Levtzion, Randall L. Pouwels pg 107-108, Les états de Kong (Côte d'Ivoire) By Louis Tauxier, Edmond Bernus pg 73-74)

Les états de Kong (Côte d'Ivoire) By Louis Tauxier, Edmond Bernus pg 75-83, The War Houses of the Watara in West Africa by Mahir Şaul pg 569-570)

Another great one, thank you so much.

Is Watara a clan among the Dyula?