The forgotten ruins of Botswana: stone towns at the desert's edge.

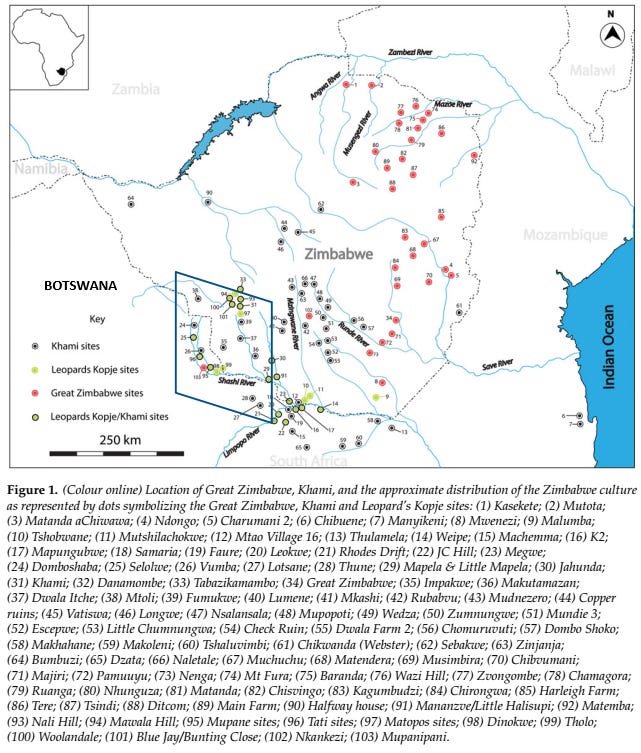

At its height in the 17th century, the stone towns of the ‘zimbabwe culture’ encompassed an area the size of France1. The hundreds of ruins spread across three countries in south-eastern Africa are among the continent’s best-preserved historical monuments and have been the subject of great scholarly and public interest.

While the ruins in Zimbabwe and South Africa have been extensively studied and partially restored, similar ruins in the north-eastern region of Botswana haven’t attracted much interest despite their importance in elucidating the history of the zimbabwe culture, especially concerning the enigmatic gold-trading kingdom of Butua, and why the towns were later abandoned.

This article explores the history of the stone ruins in northeastern Botswana, their relationship to similar monuments across south-eastern Africa, and why they later faded into obscurity.

Map of south-eastern Africa showing some of the largest known monuments of the ‘zimbabwe culture’2

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The emergence of complex societies in north-eastern Botswana and the kingdom of Butua.

Among the first complex societies to emerge in south-eastern Africa was a polity centered at the archeological site of Bosutswe at the edge of the Kalahari desert in north-eastern Botswana. The ‘cultural sequence’ at Bosutswe spans the period from 700-1700CE, and the settlement was one of several archeological sites in the region that flourished during the late 1st to early 2nd millennium CE. These sites, which include Toutswe (in Botswana), Mapela Hill (in Zimbabwe), ‘K2’, and Mapungubwe (in South Africa), among several others, are collectively associated with the incipient states/chiefdoms of Toutswe in Botswana and Leopard's Kopje in Zimbabwe&Botswana, named after their ceramic traditions and largest settlements.3

These early settlements often consisted of central cattle kraals surrounded by houses and grain storages and their material culture is associated with Shona-speaking groups, especially the Kalanga.4 The emergence of states in this region is thus associated with the growth of the internal agro-pastoral economy as well as regional and external trade in gold5, and ivory, the latter of which is represented by a 10th-century ivory cache found at the site of Mosu in northern Botswana.6

By the early second millennium, several states had emerged in southeast Africa, characterized by monumental walled capitals (dzimbabwes), the largest of which was at Great Zimbabwe. While the walled tradition of Great Zimbabwe is often thought to have begun at Mapungubwe and Mapela Hill, recent archeological studies have found equally suitable precursors in north-eastern Botswana, where several older sites with both free-standing walls and terraced platforms were discovered in the gold-producing-Tati river basin. These include the sites of Tholo, Dinonkwe, and Mupanini, which are dated to the late 12th and early 13th century.7

Many of the above settlements were gradually abandoned during the 14th century, coinciding with the decline of the polities of Mapungubwe and Toutswe during a period marked by a drier climate between 1290 and 1475. It is likely that part of the population moved to the wetter Zimbabwe plateau and contributed to the rise of Great Zimbabwe, as well as the Butua kingdom centered at Khami and the kingdom of Mutapa to the north, with the Butua kingdom having a significant influence on societies in north-eastern Botswana.8

Sketch of the political landscape in south-east Africa before the 15th century.

Unlike the extensive documentation of the Mutapa state, there were relatively few contemporary records of the Butua kingdom at Khami to its south. An account from 1512 by the Portuguese merchant Antonio Fernandez who had traveled extensively on the mainland to Mutapa mentions that: "between the country of Monomotapa and Sofala, all the kings obey Monomotapa, but further to the interior was another king, who had rebelled and with whom he was at war, the king of Butua. The latter was as powerful as the Monomotapa, and his country contained much gold."9

However, since the Portuguese activities in Mutapa’s south were restricted by anti-Portuguese rebellions, there were only a few references to Butua society between the 1512 account above, and the sack of the kingdom’s capital in 1644, in which one of the rival claimants to the throne utilized the services of a Portuguese mercenary named Sisnando Dias Bayao.10

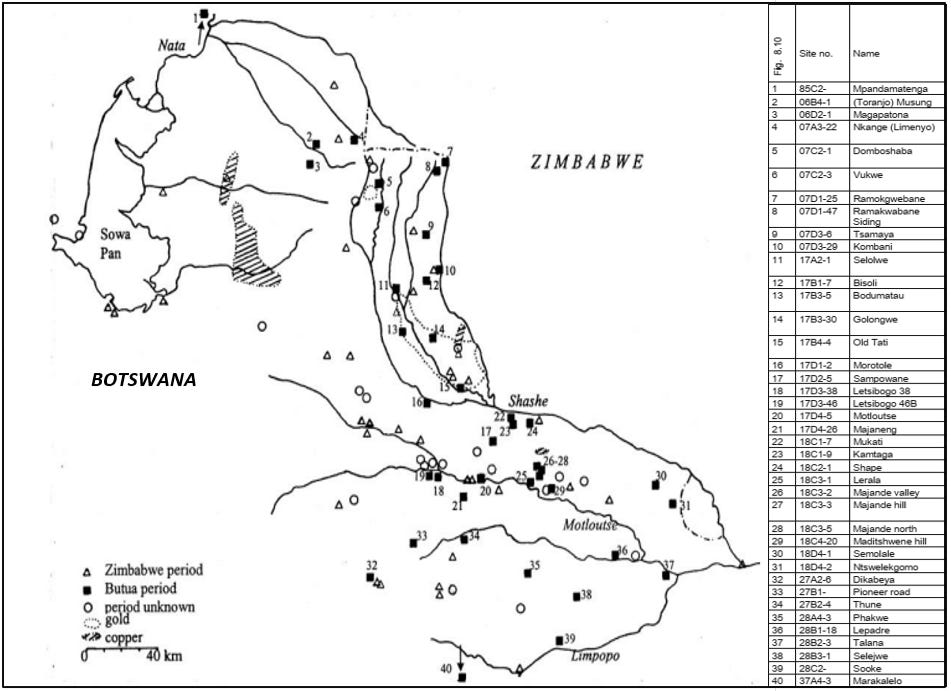

On the other hand, there’s extensive archeological evidence for the construction of Khami-style ruins dated to the ‘Butua period’ in the 15th-17th century with over 80 known sites in Zimbabwe and over 40 in Botswana.11 As well as secondary evidence for gold trade from Butua that was exported to the Swahili coastal town of Angoche, which was described in 16th-century documents as bypassing the Portuguese-controlled Sofala.12

the hill complex at Khami in Zimbabwe, capital of the Butua kingdom.

The Butua period in north-eastern Botswana: 15th-17th century.

The largest of these Butua-period sites in Botswana that have been studied include the ruins of; Sampowane, Vukwe, Domboshaba, Motloutse, Sojwane, Thune, Shape, and Majande, Lotsane whose free-standing walls are still preserved to the height of at least two meters.

The walled settlements of the Butua period were built to be monumental rather than defensive, often in places with granite outcrops from which the stone blocks used in construction were obtained. The interior of the stone settlements often contained elevated platforms and terraces, both natural and artificial, that exposed rather than concealed the leader, in contrast to the screening walls of the Great Zimbabwe sites. And like many stone settlements in southeast Africa, the different settlement sizes often corresponded to different levels in the state hierarchy, and the amount of walling was often a reflection of the number of vassals who provided labor for their construction.13

Archeologists identified four size categories for the Butua period settlements, representing a five-tiered settlement hierarchy. level 1, consists of unwalled commoner sites, level 2 sites consist of a stone wall with a platform for at least one elite house, level 3 sites (like Vukwe) have longer larger platforms for several elite houses as well as multiple tiers and entrances, level 4 sites (like Motloutse, Majande, Domboshaba, etc) have large platforms and long walling, this is where the highest of the Botswana sites fall. Levels 5 and 6, have all of these features on a monumental scale and are found in Zimbabwe (eg Khami and Zinjanja).14

Butua-period walled settlements in Zimbabwe, Map and Table by Catharina Van Waarden

Starting from the north, the largest among the best-preserved ruins is at Domboshaba, which consists of two complexes, with an almost fully enclosed hilltop ruin, and a lower section that is partially walled. Both complexes enclose platforms for elite houses, and their walls have rounded entrances and check designs in the upper courses. The site was radio-carbon dated to between the 15th-18th century making it contemporaneous with the Butua capital of Khami, with which it shares some architectural similarities, as well as a material culture like coiled gold wire and the bronze wire worn by the elites. To its south was the ruin of Vukwe which comprised a series of walled platforms, enclosing an elite complex in which iron tools and bronze jewelry were found.15

collapsed perimeter walls of the Domboshaba ruin.16

Vukwe ruin, photo at Quai Branly

South of the Domboshaba and Vukwe cluster are the ruins at Shape, which consist of several terrace platforms as well as a free-standing wall that bears a broken monolith and blocked doorway. Near these are the ruins of Majande which comprise two settlements known as Upper and Lower Majande. The two ruins have profusely decorated front walls with stone monoliths and raised platforms for elite houses. A short distance northwest of Majande is the Sampowane ruin, which comprises a complex of platforms and free-standing walls profusely decorated with herringbone, cord and check designs, and is likely contemporaneous with Majande.17

Majande ruin. photo by Mabuse Heritage Group

Sampowane ruin, photo by T. Huffman

To the south of these is the ruin of Motloutse, which consist of a double-tiered platform complex with walls of check decoration built on and around a small granite kopje, which overlooks a walled enclosure that lies below the hill. Near this is the ruin of Sojwane, which consists of free-standing walls erected between the natural boulders of the granite batholith. Its small size and lack of occupation indicate that it was likely a burial place of the senior leaders in the Motloutse valley.18

Motloutse ruin, photo by C. Van Waarden

Sojwane Ruin, photo by T. Huffman

South of these settlements is the ruin of Thune, which consists of a double enclosure with several terraced platforms surrounding the summit, and a curved wall about 14 m long.19 Much further south are the ruins of Lotsane, which were one of the earliest dzimbabwes to be described. They comprise two sets of settlement complexes, both of which have a long curved wall with rounded ends and doorways.20

sections of the Lotsane ruins21

The transition period between the Butua and Rozvi kingdoms in North-eastern Botswana: late 17th-early 18th century.

The use of check designs, and the presence of retaining walls that formed house platforms similar to the Khami-style sites of Danangombe and Naletale, indicates that Majande, Lotsane and Sampowane were occupied during the later Khami period. This is further confirmed by radiocarbon dates from Majande that estimate its occupation period to be between 1644 and 1681, making it a much later site than Domboshaba.22

The significance of the architectural similarities with other Khami settlements is connected with political developments associated with the fall of the Butua kingdom. After the sack of the Butua capital of Khami during the dynastic conflict of 1644, the victor likely moved his capital to Zinjanja, where a large settlement was built with walls covered in elaborate designs expressing various aspects of sacred leadership.

Archeological evidence indicates that settlement at Zinjanja was shortlived, as the ascendancy of the Rozvi state (1680-1840) with its capital at Danangombe and Naletale eclipsed the former's power by the turn of the 17th century. Several of the ruins in N.E Botswana were built during this Interregnum Phase (AD 1650–1680) between the fall of Butua and the rise of the Rozvi, a period marked by dynastic competition, unchecked by the relatively weak rulers at Zinjanja. The striking wall decorations at Sampowane and Majande ruins are similar to those used by the rulers of Zinjanja, rather than the Butua rulers of Khami. They predominantly feature herring board and cord designs, rather than the profuse check designs seen at Khami and later at Danangombe.23

check designs at the ruins of Danangombe in Zimbabwe, photo at Quai Branly

detail of a collapsed wall of the Zinjaja ruin in Zimbabwe, showing herringbone designs

herringbone designs on the Majande ruin in Botswana, photos by T. Huffman

Origins of the golden trade of the Butua kingdom

The majority of the ruined settlements in north-eastern Botswana were established near gold and copper mines. There are over 45 goldmines in north-eastern Botswana between the Vumba and Tati Greenstone Belts, each consisting of a number of prehistoric and historic mine shafts and trenches, flanked by milling sites containing cup-shaped depressions where the gold was extracted from the ore.

Evidence for Copper mining and smithing is even more abundant, including mines, smelting furnaces, crucibles, tuyeres, and slag, that were found near several ruined towns including Vukwe, Matsitama, Majande, Shape. While most gold mines were found near level 1 (commoner) sites, some of the larger ruins such as Vukwe, Domboshaba, and Nyangani were all located near the edge of the gold belt. In this predominantly agro-pastoral economy, mining would have been carried out on a seasonal basis, just as it was documented in Mutapa.24

Ivory and Ironworking, as well as the manufacture of cotton textiles, are all attested at several sites based on the presence of ivory artifacts, numerous iron furnaces and material, spindle whirls used in weaving cotton, and documentation of the use and trade of ivory, iron and local cloth, exchanged for imported glass and cloth. The lack of elite control over these specialist activities like ironworking and prestige/trading items like copper, gold, and ivory, suggests that power was obtained through a combination of religious authority, accumulating wealth and followers, as well as the construction of monumental palaces.25

The political structure of societies in north-eastern Botswana thus resembled that in the Butua kingdom of Khami, which combined interpolity heterarchies and intra-polity hierarchies.26 Additionally, the organization of trade, whether in domestic markets for agro-pastoral products or to external markets for commodities like gold and copper, would not have been centrally controlled but undertaken by independent traders, like those documented in 17th century Mutapa.

Map of the gold-producing regions in north-eastern Botswana, and the rest of southeast Africa.27

Collapse of the stone towns of north-eastern Botswana.

By the early 19th century, political and social transformations associated with the so-called mfecane profoundly altered the cultural landscape of north-eastern Botswana. Rozvi traditions describe the decline of the Changamire state due to dynastic conflicts, which exacerbated its collapse after it was overrun by several groups including the Tswana-speaking Ngwato, and several Nguni-speaking groups like the Ndebele and Ngoni, all of whom subsumed the Kalanga-speaking societies.28

The period of Ndebele ascendancy in North-Eastern Botswana in the mid-19th century was especially disruptive to the local polities. As recounted in Ndebele traditions and contemporary documents, some of the defeated Kalanga leaders often fled with their followers to hilltop fortresses, or outside the reach of the Ndebele to regions controlled by the Ngwato, while some were retained as vassals. The region remained a disputed frontier zone caught between two powerful states, many of the old towns were abandoned, and the authority of those who remained was greatly diminished.29

There's documentary and archeological evidence for the rapid abandonment of these ruins, and the later re-occupation of a few of them. An account from 1870 mentions the abandonment of the Vukwe ruin by its Kalanga ruler following a Ndebele campaign into the region, and there’s archeological evidence for the partial re-settlement of Domboshaba during the mid-19th century, with the new settlement being established in a more elevated and defensible region of the hill, where further walling was added.30

Additionally, many of the ruined settlements have blocked doorways that were sealed with stone monoliths, especially at Majande and Shape, which was a common practice attested at many dzimbabwes across the region (eg at Matendere in Zimbabwe). These blocked doorways denied access to sacred spaces, especially when rulers moved their capital upon their installation, marking the end of the enclosed palace’s administrative use, and the abandonment of part or all of the site.31

It is important to note that the construction of stone settlements in the region had mostly ended by the early 18th century, since no new settlements post-date this period, representing a cultural shift that was likely caused by internal processes. Nevertheless, the connection between the stone towns and their former occupants was largely severed. With the exception of Domboshaba, few of the Kalanga traditions collected in the 20th century could directly link the sites to specific lineages and rulers, as most of their counts were instead focused on the upheavals of the 19th century.32

Unlike the monumental capitals in Zimbabwe where such traditions were preserved, memories of the stone towns of north-eastern Botswana were forgotten, as their ruins were gradually engulfed by the surrounding desert-shrub.

section of the Lotsane ruin when it was first photographed in 1891.33

While there are few written accounts for pre-colonial south-east Africa, the expansion of trade contacts between south-central Africa and the Swahili coast led to the production of detailed documentation of the region's societies by other Africans.

subscribe to Patreon to read about the account of one of these visitors who traveled to Congo and Zambia in 1891:

taken from the introduction of “Zimbabwe Ruins in Botswana: Settlement Hierarchies, Political Boundaries and Symbolic Statements” by Thomas N. Huffman & Mike Main

Map by Shadreck Chirikure et al, from “No Big Brother Here: Heterarchy, Shona Political Succession and the Relationship between Great Zimbabwe and Khami, Southern Africa.”

Archaeological excavations at Bosutswe, Botswana: cultural chronology, paleo-ecology and economy by James Denbow et al., The Iron Age sequence around a Limpopo River floodplain on Basinghall Farm, Tuli Block, Botswana, during the second millennium AD by Biemond Wim Moritz pg 6-7, 65, 234)

The Iron Age sequence around a Limpopo River floodplain by Biemond Wim Moritz pg 66, 125, 152, 162, Butua and the End of an Era: The Effect of the Collapse of the Kalanga State on Ordinary Citizens by Catrien Van Waarden pg 25-27

Butua and the End of an Era: The Effect of the Collapse of the Kalanga State on Ordinary Citizens by Catrien Van Waarden pg 32-33,

An ivory cache from Botswana by Andrew Reid and Alinah K Segobye

The Origin of the Zimbabwe Tradition walling by Catrien Van Waarden pg 59-69)

Butua and the End of an Era: The Effect of the Collapse of the Kalanga State on Ordinary Citizens by Catrien Van Waarden pg 50, 356

Butua and the End of an Era: The Effect of the Collapse of the Kalanga State on Ordinary Citizens by Catrien Van Waarden pg 49)

An archaeological study of the zimbabwe culture capital of khami by T. Mukwende pg 15

Butua and the End of an Era: The Effect of the Collapse of the Kalanga State on Ordinary Citizens by Catrien Van Waarden pg 79-81)

A History of Mozambique By M. D. D. Newitt pg 10-12, 22 An archaeological study of the zimbabwe culture capital of khami by T. Mukwende pg 38

Butua and the End of an Era: The Effect of the Collapse of the Kalanga State on Ordinary Citizens by Catrien Van Waarden pg 82, 179-180)

Butua and the End of an Era: The Effect of the Collapse of the Kalanga State on Ordinary Citizens by Catrien Van Waarden pg 84)

Recent Research at Domboshaba Ruin, North East District, Botswana by Nick Walker, Butua and the End of an Era: The Effect of the Collapse of the Kalanga State on Ordinary Citizens by Catrien Van Waarden pg 91, 231)

Facebook photo

Zimbabwe Ruins in Botswana: Settlement Hierarchies, Political Boundaries and Symbolic Statements by Thomas N. Huffman & Mike Main pg 372, Butua and the End of an Era: The Effect of the Collapse of the Kalanga State on Ordinary Citizens by Catrien Van Waarden pg 90)

Zimbabwe Ruins in Botswana: Settlement Hierarchies, Political Boundaries and Symbolic Statements by Thomas N. Huffman & Mike Main pg 373-4)

Zimbabwe Ruins in Botswana: Settlement Hierarchies, Political Boundaries and Symbolic Statements by Thomas N. Huffman & Mike Main pg 373, Butua and the End of an Era: The Effect of the Collapse of the Kalanga State on Ordinary Citizens by Catrien Van Waarden pg 89

The Archaeology of the Metolong Dam, Lesotho, by Peter Mitchell, pg 15-18, Settlement Hierarchies in the Northern Transvaal : Zimbabwe Ruins and Venda History by T. Huffman pg 8-10

Reddit photo by /u/Hannor7 and Facebook photo by Mike Techet

Zimbabwe Ruins in Botswana: Settlement Hierarchies, Political Boundaries and Symbolic Statements by Thomas N. Huffman & Mike Main pg 371-372, 376)

Zimbabwe Ruins in Botswana: Settlement Hierarchies, Political Boundaries and Symbolic Statements by Thomas N. Huffman & Mike Main pg 379-384, Butua and the End of an Era: The Effect of the Collapse of the Kalanga State on Ordinary Citizens by Catrien Van Waarden pg 252)

Butua and the End of an Era: The Effect of the Collapse of the Kalanga State on Ordinary Citizens by Catrien Van Waarden pg 230)

Butua and the End of an Era: The Effect of the Collapse of the Kalanga State on Ordinary Citizens by Catrien Van Waarden pg 234-235

No Big Brother Here: Heterarchy, Shona Political Succession and the Relationship between Great Zimbabwe and Khami, Southern Africa by Shadreck Chirikure et. al.

Maps by Catrien van Waarden, and Shadreck Chirikure

Butua and the End of an Era: The Effect of the Collapse of the Kalanga State on Ordinary Citizens by Catrien Van Waarden pg 243-245, 353-354)

Butua and the End of an Era: The Effect of the Collapse of the Kalanga State on Ordinary Citizens by Catrien Van Waarden pg 251-267)

Butua and the End of an Era: The Effect of the Collapse of the Kalanga State on Ordinary Citizens by Catrien Van Waarden pg 267, 277-281, 334-335, 341)

Zimbabwe Ruins in Botswana: Settlement Hierarchies, Political Boundaries and Symbolic Statements by Thomas N. Huffman & Mike Main pg 376-377)

Butua and the End of an Era: The Effect of the Collapse of the Kalanga State on Ordinary Citizens by Catrien Van Waarden pg 354, 357

‘Ruins at junction of Lotsina with Crocodile River’ by William Ellerton Fry, reproduced by Rob S Burrett and Mark Berry

![https://www.quaibranly.fr/en/explore-collections/base/Work/action/list/mode/thumb?orderby=null&order=desc&category=oeuvres&tx_mqbcollection_explorer%5Bquery%5D%5Btype%5D=&tx_mqbcollection_explorer%5Bquery%5D%5Bclassification%5D=&tx_mqbcollection_explorer%5Bquery%5D%5Bexemplaire%5D=&filters[]=Jacqueline%20Roumegu%C3%A8re-Eberhardt%7C1%7C&filters[]=vukwe%7C2&refreshFilters=true&refreshModePreview=true https://www.quaibranly.fr/en/explore-collections/base/Work/action/list/mode/thumb?orderby=null&order=desc&category=oeuvres&tx_mqbcollection_explorer%5Bquery%5D%5Btype%5D=&tx_mqbcollection_explorer%5Bquery%5D%5Bclassification%5D=&tx_mqbcollection_explorer%5Bquery%5D%5Bexemplaire%5D=&filters[]=Jacqueline%20Roumegu%C3%A8re-Eberhardt%7C1%7C&filters[]=vukwe%7C2&refreshFilters=true&refreshModePreview=true](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!shcq!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F85cc08da-4479-4690-9362-911b8dcc6e36_839x573.png)

Enlightening read! Thank you!

Incredible work. Do keep it up. This armchair historian will keep reading