The historic architecture of Ethiopia and Eritrea: a complete overview

The modern countries of Ethiopia and Eritrea are home to some of the best-known historic architectural monuments in Africa.

These ancient buildings, which are among the largest collections of stone structures on the continent, are a testament to the architectural ingenuity and cultural diversity of the societies which flourished in the northern Horn of Africa.

The architecture of Ethiopia and Eritrea has its roots in indigenous building traditions and broader stylistic currents from the Red Sea region, the Eastern Mediterranean, and the Indian Ocean world.

It encompasses a wide range of building typologies, including rock-hewn churches carved directly from volcanic rock, distinctive castle complexes, and an array of monumental constructions, such as cathedrals, monasteries, palaces, mosques, shrines, and temples.

This article outlines the architectural history of Ethiopia and Eritrea since the emergence of the earliest complex societies in the region, and provides a brief overview of many of the most notable monuments from the region.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by joining our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Origins of the earliest building traditions of Ethiopia and Eritrea: from the Neolithic Gash group to the pre-Aksumite cultures (ca. 3000-400 BC)

Beginning in the 3rd millennium BC, complex societies and states arose in the northern Horn of Africa, many of which influenced the development of the region’s architecture.

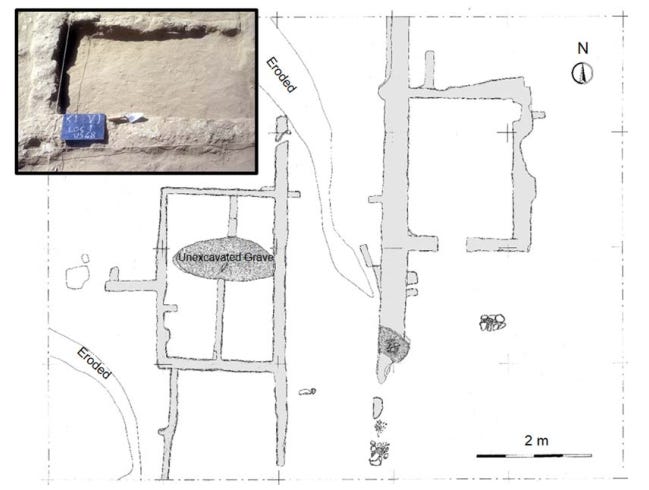

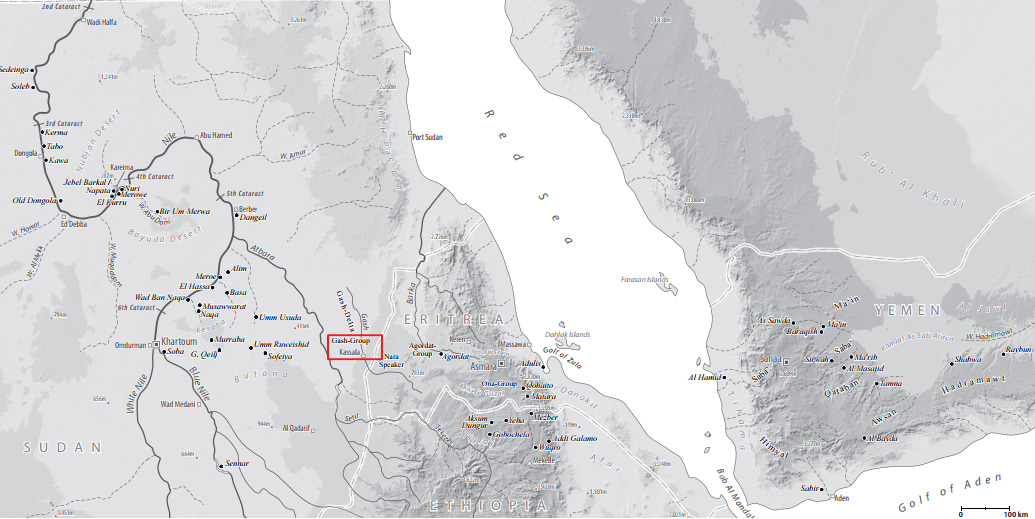

The oldest of these was the Gash group (c. 3000–1500/1400 BC), a Neolithic society centered around the site of Mahal Teglinos in Kassala, Sudan, but extending to parts of Eritrea and the Sudan/Ethiopia border region. Architectural remains found at this ancient capital consist of two large rectangular mud-brick buildings with storerooms dating to the late 3rd/early 2nd millennium BC, and an elite cemetery with funerary stelae comprised of flat slabs, pointed monoliths, and small pillars.1

The earlier of the two buildings was constructed on the eastern fringes of the central sector of the site, and is characterized by associated fireplaces. The latter structure is better preserved with a couple of small rectangular rooms and a larger elongated one in the central sector of the site. The two buildings represent the southernmost examples of such structures in Africa south of Nubia during the 3rd-2nd millennium BC.2

The material culture recovered from the site, which included imports of Nubian and Egyptian provenance, suggests it may have been the location of the enigmatic ‘Land of Punt’.

Early 2nd millennium bc mud brick structure at Mahal Teglinos, plan and detail. Image by A. Manzo

Mahal Teglinos (Kassala), Stele Field, Gash Group. image by R. Fattovich

Ancient archaeological sites in the northern Horn of Africa, Nubia, and Yemen. Map by Nicole Salamanek

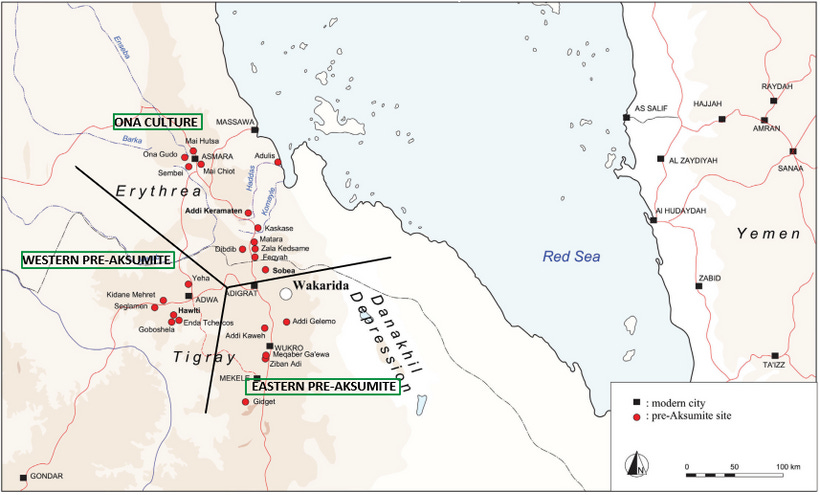

Elite structures and funeral monoliths reappear in the northern Horn region during the early 1st millennium BC at the pre-Aksumite sites between Tigray (in northern Ethiopia) and Eritrea.

The westernmost sites of Yeha, Hawlti, Malazo, etc, and others contain the remains of stone temples, palaces, cemeteries, and inscriptions. The northern and eastern sites of the greater Asmara area, as well as in Wakarida and Gulo Makeda region of Tigray, contain the remains of rectilinear stone buildings and cemeteries topped with stele, but with no public buildings or signs of hierarchy.3

These groups of sites represent the two main cultural influences discernible in the archaeological record. The more dominant of which was indigenous in origin (especially in the domestic architecture of the eastern and northern sites), but with a significant contribution from the contemporaneous south-Arabian polity of Saba, (especially in temple architecture). The material culture and the inscriptions found at the sites indicate that most of the occupants were speakers of the ‘Old Ethiopic’ or ‘Proto-Ge’ez’ language.4

A map showing the distribution of pre-Aksumite sites in Ethiopia. Map by Anfray & Anne Benoist et al. Labels by author.

Domestic architecture of the pre-Aksumite period is well preserved in the sites of the Greater Asmara area (such as Sembel, Mai Hutsa, Ona Gudo) and the site of Wakarida in Tigray. In these sites, house walls were made of closely fitted fieldstones held together with clay mortar and built on top of platforms with associated terraces and cisterns. Material from the sites indicates that they were constructed in the 8th-5th century BC, and showed no links to the Sabean polities of South Arabia.5

Pre-Aksumite structure at Alakile Daga, Wakarida, Tigray, Ethiopia. Image by Anne Benoist et al.

The Stone Walls found at the pre-Aksumite site of Sembel, Eritrea.

At Yeha, the temple and palace were constructed between the 8th to 6th centuries BC. They were both built on a podium and featured monumental staircases, high roofs supported by square pillars. The temple’s walls were built using well-dressed limestone blocks that were set without mortar, while the palace walls were built with undressed stone set in clay mortar. Similar, albeit smaller, temples were built at other sites, and they contain small altars resembling the temple at Yeha, which was in turn based on Sabean temples of Almaqah, but with inscriptions mentioning names of local rulers. The site’s material culture consisted mostly of local handmade pottery common in other pre-Aksumite sites.6

The Great Temple in Yeha, Tigray, Ethiopia. Image by Pawel Wolf et al.

Temple of Meqaber Ga‘ewa near the town of Wukro, Tigray, Ethiopia. Image by Pawel Wolf et al.

Interior of the Grat Be’al Gebri palace at Yeha, Ethiopia.

Aksumite architecture (ca. 100BC-700CE)

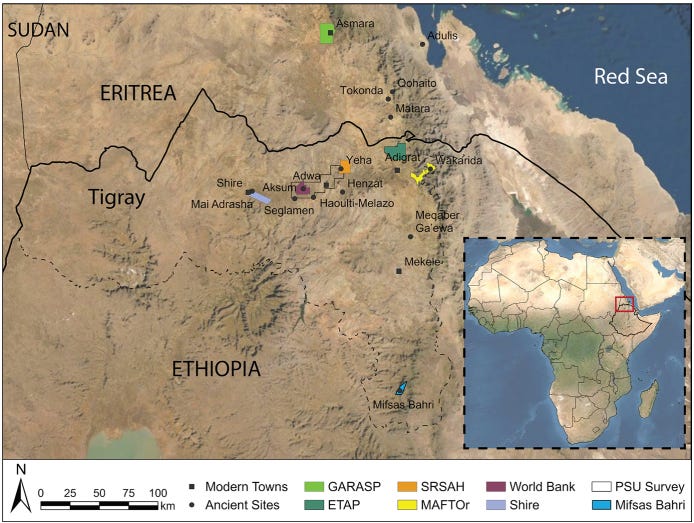

The domestic and elite architecture of the early 1st millennium BC formed the prototype of the construction styles used in the Aksumite period. This process was gradual, beginning around 400 BC with the ‘proto-Aksumite’ capital at Bieta Giyorgis hill (1 km north of Aksum), and later shifting to the site of Aksum by the late 1st century CE.

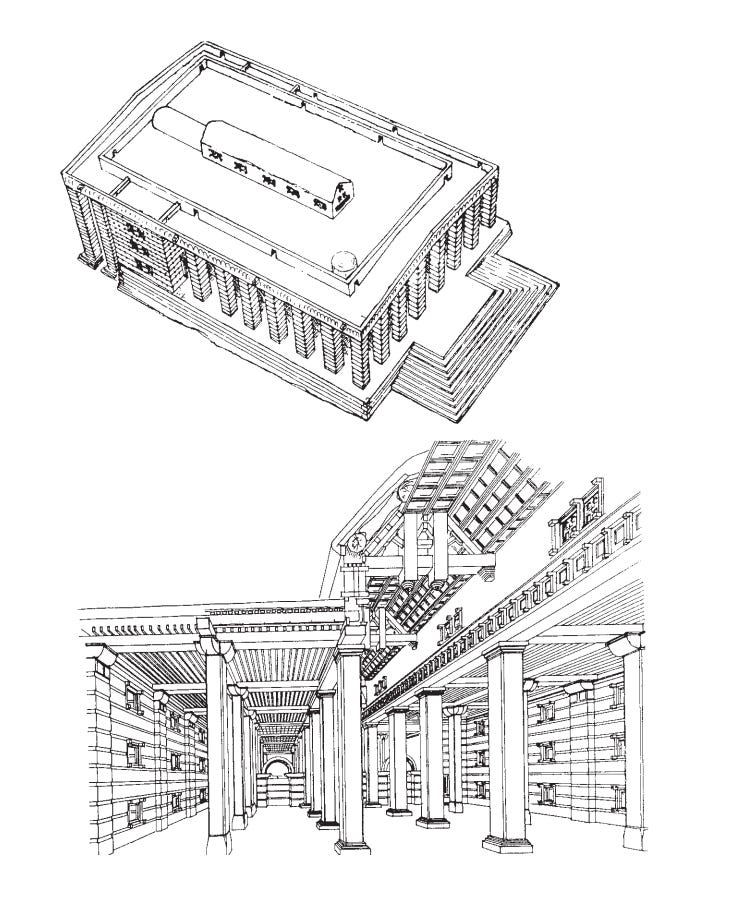

Walls were mostly built of rough stone masonry set in clay-mortar (rarely with lime mortar), strengthened at the corners by massive ashlar blocks. The walls incorporated horizontal beams held together by transverse beams whose rounded ends that extended outside the façade were called ‘monkey-heads’. Flat roofs were supported by stone pillars with stepped bases, arches were made of fired bricks, and floors were made of stone paving.7

Elite structures/villas comprised a central building set on a high foundation or plinth with stepped sides. The central structure was set in an open court, surrounded by ranges of rooms. Domestic structures consisted of densely-packed houses with narrow rooms surrounding open courtyards. The walls were built with undressed stone set in clay mortar, and the houses had both flat and gable roofs. Examples of both elite and domestic structures can be found at Aksum, Matara, Wakarida, among other sites.8

The Dungur ‘Palace’ at Aksum.

Aksumite villa at Wakarida, Tigray, Ethiopia. Image by X. Peixoto, reproduced by Anne Benoist et al.

Domestic architecture at Aksum

Stele field and Mausoleum of Aksum

Some of the main Aksumite settlements. Map by Michael J. Harrower et al.

Aksumite elites initially recognized many religions before their adoption of Christianity around 333 and 340 CE. However, no remains of non-Christian structures are known from the period after the collapse of the pre-Aksumite societies. Churches were thus the main type of religious architecture from the Aksumite period, especially basilica churches, which were found at Aksum and the port-town of Adulis.

Besides the 4th-century cathedral of Maryam Tsion, which was reconstructed much later, the oldest among the early Aksumite basilicas are the two churches found at Adulis, one of which is a large cathedral dated to 400-532 CE, and a small domed church dated to 480-625 CE.9

Cathedral of Adulis, Eritrea. image by S. Bertoldi and G. Castiglia

Ruins of the Cathedral of Adulis, Eritrea.

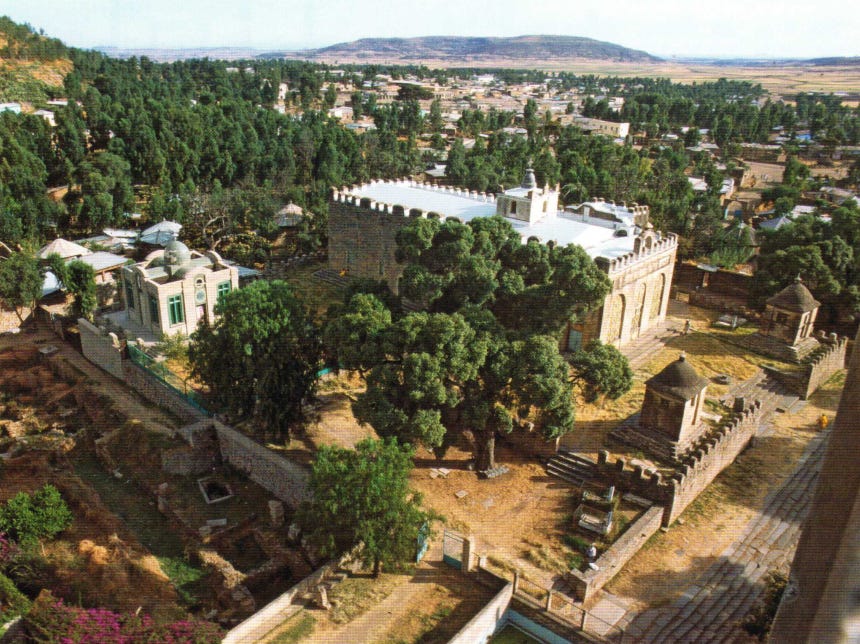

The 17th-century church of Maryam Tsion, standing on the much larger podium of the 4th-century Aksumite cathedral. Image by David W. Phillipson.

reconstructions of the original Maryam Tsion Cathedral at Aksum by Buxton & Matthews

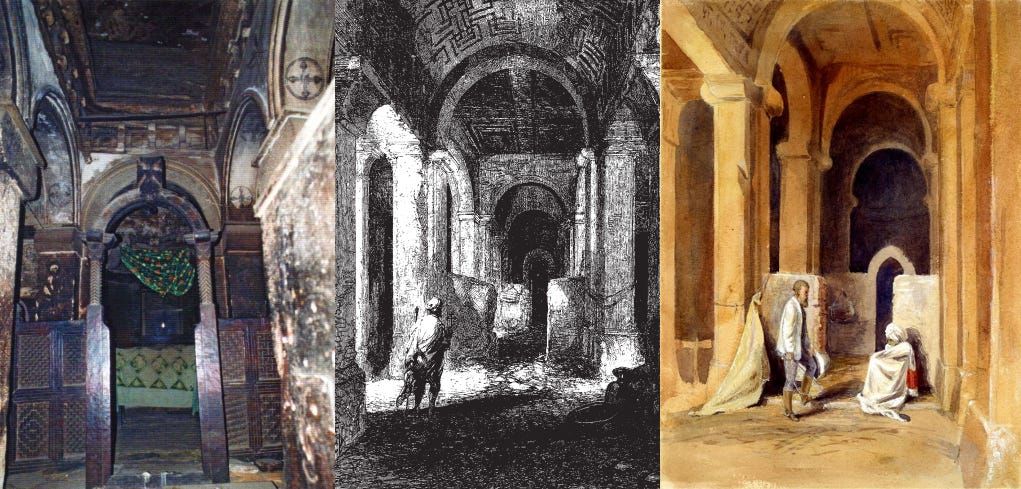

Like most Aksumite churches, these were stone-and-timber constructions built on a large platform with indented, stepped-back walls, and with a single aisle on either side of a central nave. Others were funerary churches built over subterranean rock-cut tombs. Some possessed rock-cut cisterns that supplied water to the monastic communities. These early churches can be found at Asmara, Debre Libanos-Ham, Toconda, and Matara (Eritrea), at Debre Damo, Edaga Hamus, Agula, and Mika’el Debra Selam (Tigray). These are mostly dated to the late Aksumite period.10

Debre Damo, main church and tower. Image by David W. Phillipson.

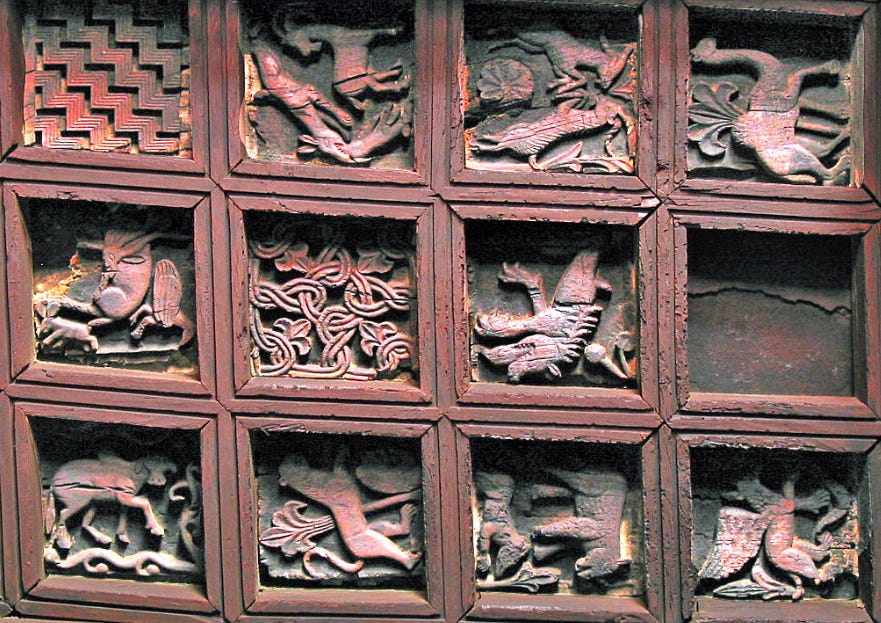

Walls of the church and details of its vestibule ceiling. Image by Jan Tromp.

Ruins of an Aksumite church at Toconda, Eritrea, ca. 1905. Archivio fotografico, Societa geografica, Italy.

Interior of the Churches of Mika’el Debra Selam, Tcherqos Wukro, and Dongolo, near Adigrat. Tigray, Ethiopia.

Ethiopian architecture during the Middle Ages: Rock-cut churches, stone tumuli and mosques.

Between the late Aksumite period (7th-11th century) and the Zagwe era (11th-13th century), the construction of rock-cut churches proliferated across the region, extending from Eastern Tigray and adjacent regions in Eritrea, to the northern parts of Ahmara, including the famous churches of Lalibela.

Most were basilican churches built in Aksumite style with flat or vaulted ceilings, decorative wooden beams and monkey-heads, arched windows and doors, and colonades. Extensive mural paintings survive in the interior of most churches, as well as finely carved relief scenes and stone screens. Some of the churches of Lalibela were initially carved by a pre-Christian population as defensive structures, before they were later transformed into religious structures.11

The church of Yemrehanna Krestos, Ahmara, Ethiopia.

The church of Beta Giyorgis, Lalibela, Amhara, Ethiopia.

Pre-Christian relief sculptures on the walls of the Washa Mika’el church, south of Lalibela. Image by A. Garric (Lalibela Mission 2017), Marie‐Laure Derat et al.

The Zagwe rulers and the Solomonic monarchs who succeeded them in 1270 did not maintain a fixed capital until the founding of Gondar in the 17th century. The old monastic structures, like the rock-churches of Lalibela and Tigray, and the round churches with square sanctuaries in the southern provinces (whose construction began around the 16th century), remained the only fixed socio-economic and religious centers in the landscape.12

The Christian kingdom was flanked by non-Christian (pagan) societies and a few Muslim polities to its north, which also produced a diverse range of architectural traditions.

Burial monuments were built and used between the 8th and 12th centuries in the Chercher Mountains south of Harar, the Shay Culture of Shewa, and in south-east Wallo, at sites such as Tätär Gur. These include tumuli, chamber tombs, and dolmen graves, which contained imported materials and artefacts, indicating trade links with the coastal regions.13

The tumulus of Tätär Gur, a passage grave built for an elite of the Shay culture during the mid-10th century. South-east Wallo, Ahmara, Ethiopia. image by François-Xavier Fauvelle-Aymar

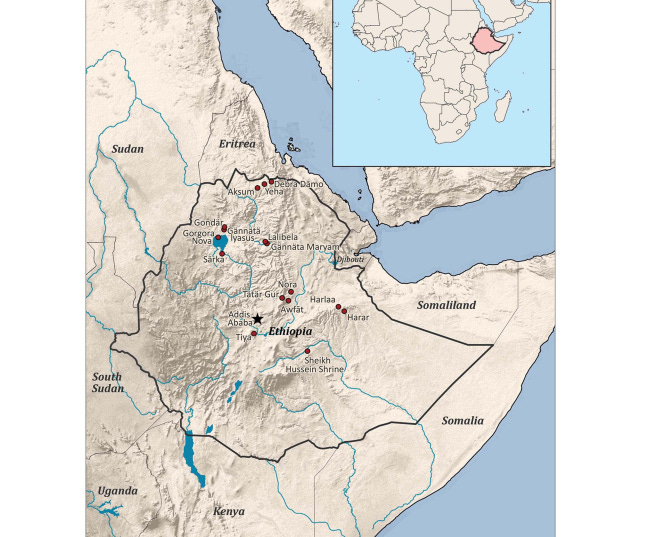

Some of the medieval sites mentioned in this section. Map by N. Khalaf, reproduced by T. Insoll.

The late medieval cities of the Muslim polities of Šawah (Shewa), Ifat, Harar, in the north-eastern region of Amhara, and other sites in the Oromia and Somali regions of the south-east14 contained several architectural monuments, including civic buildings, city walls, mosques, shrines, workshops, houses, and cemeteries dated to the 12th-17th century.

The construction style of these societies was fairly homogenous; the mosques were often square or rectangular structures built with massive stones mortared with clay. The mihrabs are usually plain, but a few were made with dressed stone. The roofs were flat, made of stone slabs, and supported by rows of timber or stone pillars.15

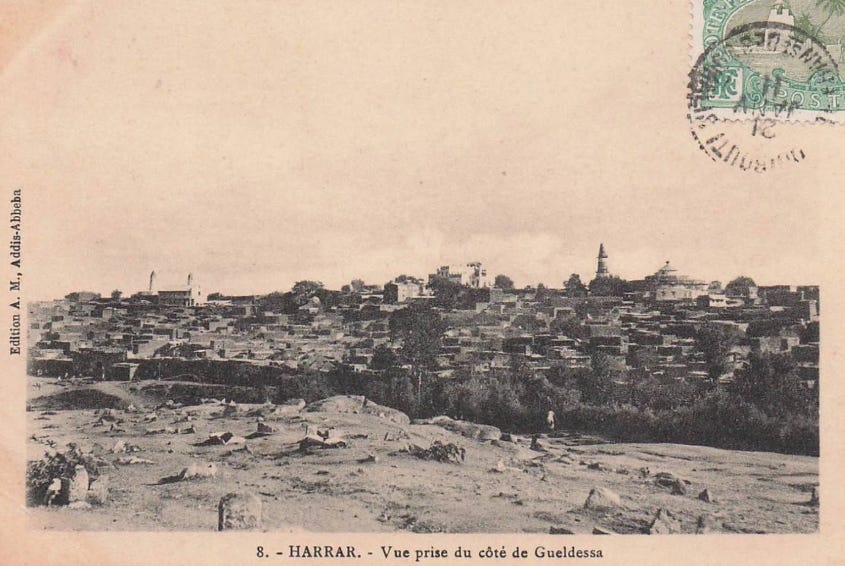

Domestic architecture consisted of square-plan habitats whose masonry walls contained small niches and were lime-plastered, similar to the extant houses of Harar. Some of these medieval structures had two storeys, similar to Richard Burton’s description of Harari houses in the mid-19th century. These were likely surrounded by more simple conical thatched structures for the poorer classes.16

Interior of the mosque at Nora. Image by T. Insoll

The main mosque of Asbari. Image from the Nora/Gendebelo Program 2009

The remnants of Balla mosque, south of Sheikh Hussein, Bale Zone of the Oromia Region. image by Terje Østebø

Square house with a wall niche at the site of Nora

Mosque of Derbi Belanbel, Somali region, Ethiopia. image by Wagaw Bogale

Castle houses near Harar, Ethiopia. images by Meftuh S. Abubaker.

Harar, Ethiopia. ca. 1884.

Gondarine Architecture and its precedents (1500-1800 CE)

Between the 15th and early 17th century, a distinct architectural tradition emerged in the Christian kingdom that combined pre-existing building styles with imported styles brought by foreign craftsmen.

Initially, these consisted of prestigious royal monasteries built from ashlar blocks ornamented with rich relief carving. Their walls were embellished with gold plating, rich fabrics, and painted murals; they had high ceilings and several courtyards. Most of these churches, such as Däy Giyorgis, Mäkanä Śǝllase, Atronsä Maryam, Märṭulä Maryam, were destroyed during the Adal invasion between 1525-1542.17

Their geographic distribution ranges from eastern Shewa in Oromia to Lake Ṭana in Ahmara and the northern region of Tigray.

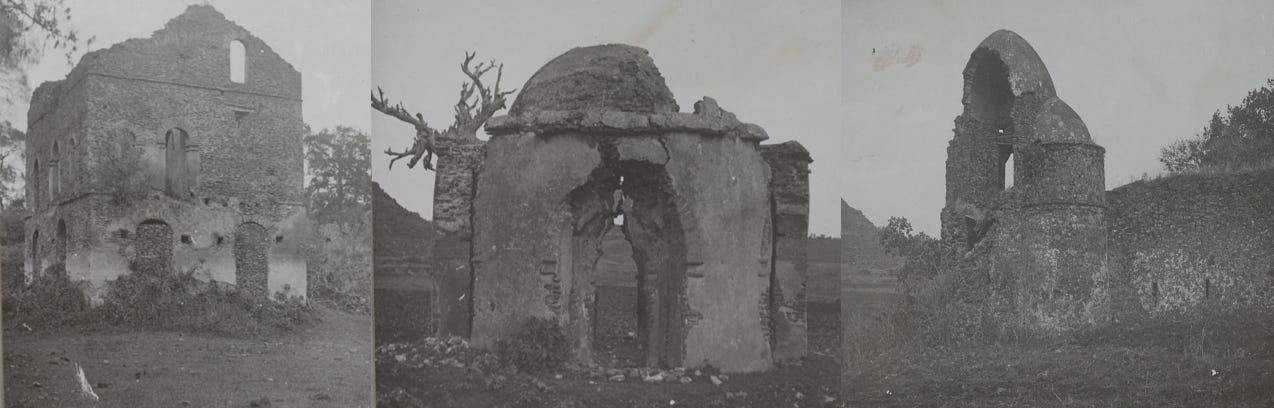

Ruins of Däy Giyorgis. image by S Chojnacki

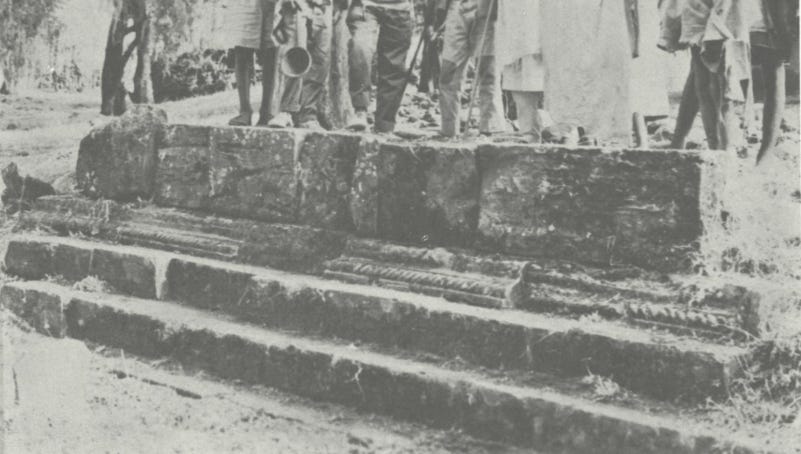

Upper view of the Ǝleni chapel pedestal. image by Victor M. Fernández et al.

Carved stones from various 15th-16th century Ethiopian churches. images by Marie-Laure Derat

After the restoration of the kingdom by Gälawdewos in the mid-16th century, Ethiopian monarchs rebuilt some of the ruined monasteries. They also invited a Jesuit mission (1557 to 1632), whose diverse group of masons (Indian, Portuguese, Ethiopian) constructed a handful of churches, residences and forts at Fǝremona (in Tigray) and Gorgora (in Amhara), which used flat stones laid horizontally in clay mortar, or in chunambo (an Indian word for lime mortar), as well as ashlar blocks and carved reliefs.18

“fortress” walls of Fǝremona, the 17th-century Jesuit residence in Tigray, Ethiopia. image by Victor M. Fernández et al.

Jesuit residence at Gorgora Nova, Amhara, Ethiopia.

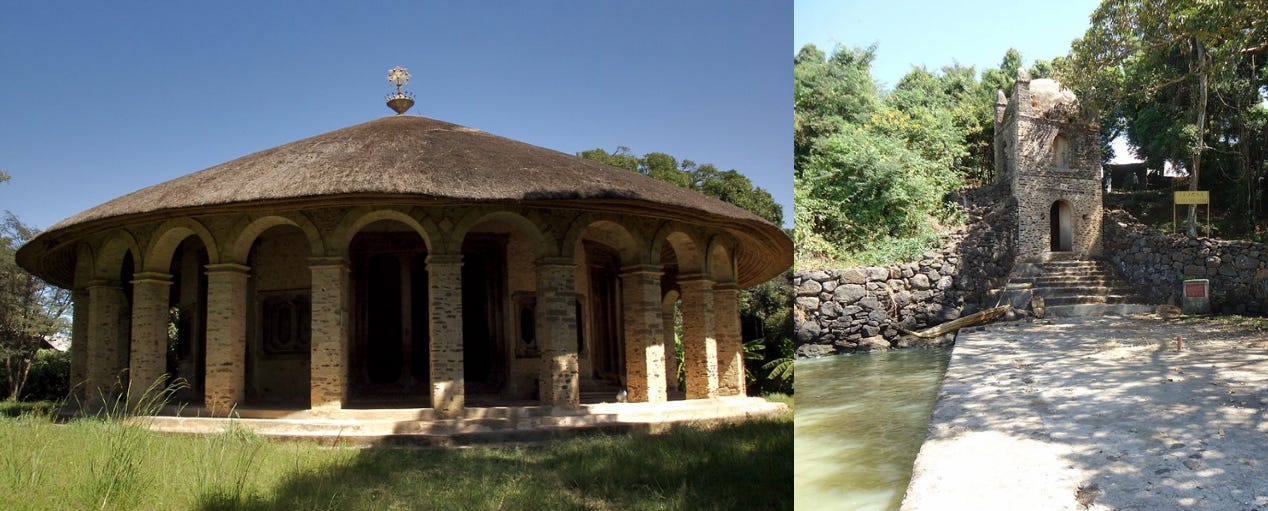

The Jesuit mission was expelled by Fasilädäs, who founded the royal capital of Gondar in 1636. Fasiladas commissioned the construction of several churches and bridges in Gondar, as well as a city wall and a large castle at the capital, a smaller castle at Guzara, a royal bath at Qaha, and a reconstruction of the ancient cathedral at Aksum.

Fasiladas’ palace at Gondar, Ethiopia.

The Guzara castle of Fasilidas at Ǝnfraz. image by Victor M. Fernández et al.

Fasilädäs’s 17th-century reconstruction of the Māryām Şĕyon church at Aksum.

Some of the churches built around Gondar by Fasilidas. ca. 1932, Quai Branly Museum.

The bridge over the River Garno, between Däbsan and Guzara, dated to the reign of Fasilidas. Image by image by Victor M. Fernández et al.

These structures were typically constructed with rough stones set in lime mortar, creating a distinct style of masonry that was different from that used by the Jesuit mission. While they were derived from defensive architecture, the castles had no military function, but were instead designed to celebrate the identity and achievements of each of the kings who built them and to enhance the image of Solomonic kingship.19

The castles featured round corner-towers with domes, battlemented parapets, square towers that rise high above terraced roofs, monumental entrance staircases, doors and windows in full, decorated arches resting on double-bracket capitals, string courses, wooden balconies, and barrel-vaulting. Churches, both round and rectangular, were encircled by stone walls with battlemented towers and monumental entrance gates.20

The Gondarine monarchs built several more churches and castles across the kingdom, which enabled the development of a local class of craftsmen. The Ethiopian mason Wáldá Giyorgis oversaw the construction of the castles of Yohannes I and his son Iyasu I, while Bajerond Issayas constructed the palaces of Empress Mentewab.21

The craftsmen of Gondar and its environs also included a sizeable number of Betä Ésraýel/Falasa (Ethiopian Jews) whom the Scottish traveler James Bruce later described, doubtless with his customary exaggeration, as “the only potters and masons” in the country. They constructed the split-cane ceiling of the palace of Emperor Iyasu II (1730-1755)22

Chancery and Library of Yohannes

Iyasu’s Palace.

Iyasu II’s church of Debre Berhan Selassie near Gondar.

Empress Mentewab’s Banqueting Hall of the Dabra Sahay Qwesqwam complex, outside Gondar

Empress Mentewab’s Narga Selassie monastery in Lake Tana. The round church with a square tower entrance.

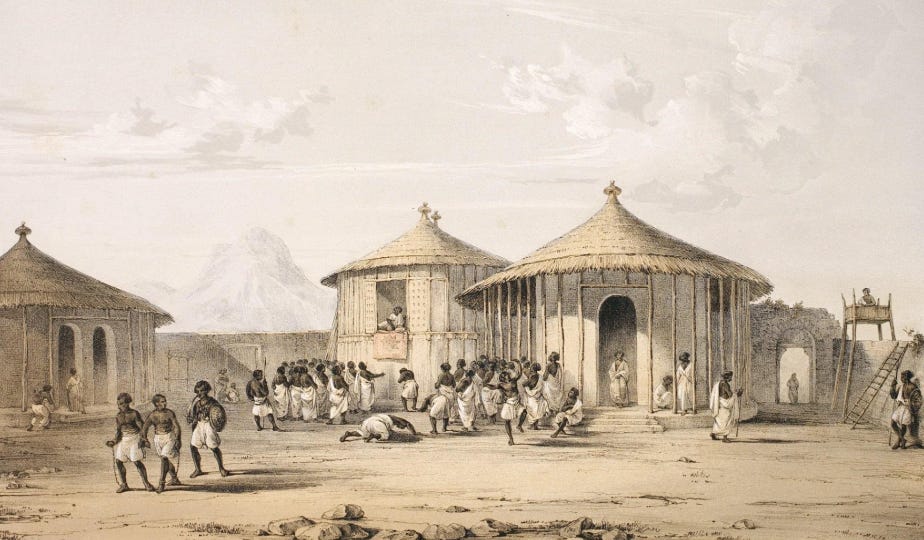

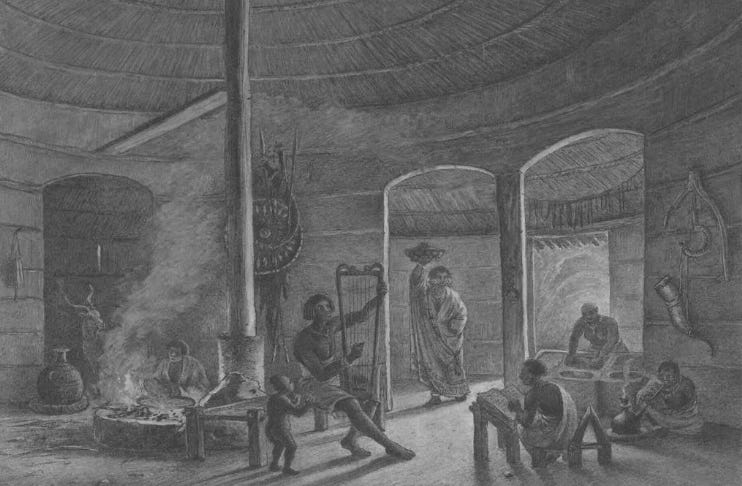

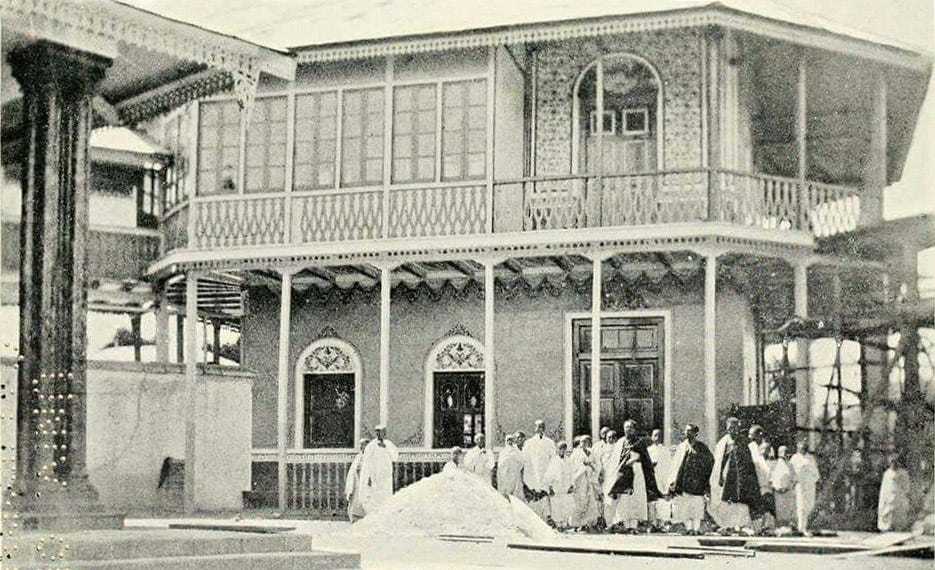

Domestic architecture of the 16th century is described by the Portuguese envoy Francisco Alvares, who saw “good large houses of one storey, with flat roofs” in Débarwa and Massawa (Eritrea), and houses with “good walls and flat roofs” at Yéha and Aksum that were better than anywhere else in Ethiopia. Later accounts from the 18th and 19th centuries indicate that, beyond the northern and eastern regions, most of the homes, including those belonging to titled persons, were round structures with conical roofs that varied in size depending on the wealth of the owner.23

The banquet hall in King Sahle Sellase’s palace, ca. 1852, at Ankober, Shewa, Amhara, Ethiopia. Illustration by Johannes Martin Bernatz

Part of the Royal Court, the king Sahla Sellase, sitting in judgement. Illustration by Johannes Martin Bernatz

Interior of a dwelling at Ankober, Amhara, Ethiopia. Illustration by Johannes Martin Bernatz

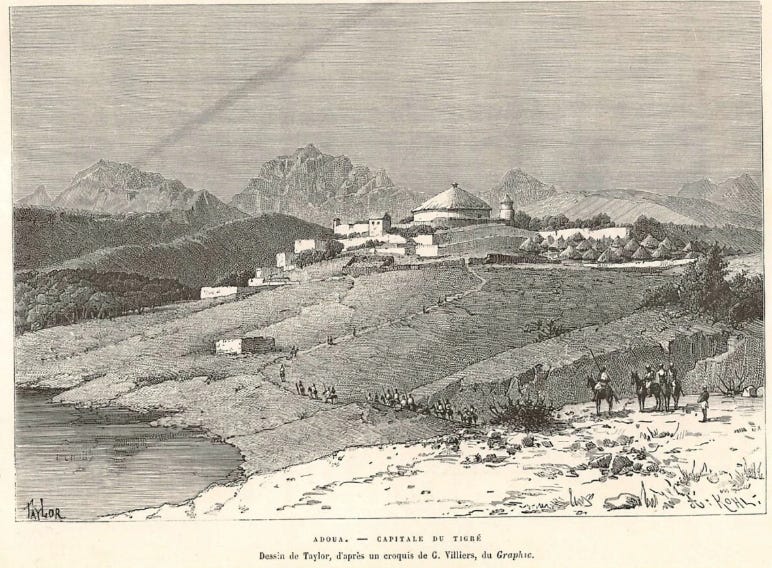

Adoua (Adwa) ‘capital of Tigre’ early 19th-century engraving.

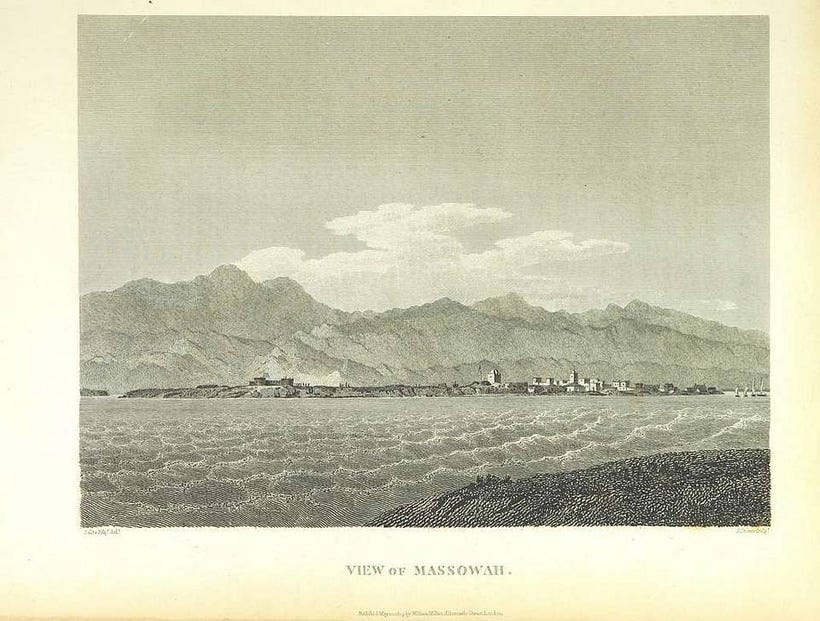

Massawa, Eritrea, in 1809. Illustration by Henry Salt

In the eastern and southern regions, the expansion of Muslim intellectual and commercial networks, especially from Harar, resulted in the proliferation of shrine and mosque construction in the polities of Wallo and Bale.

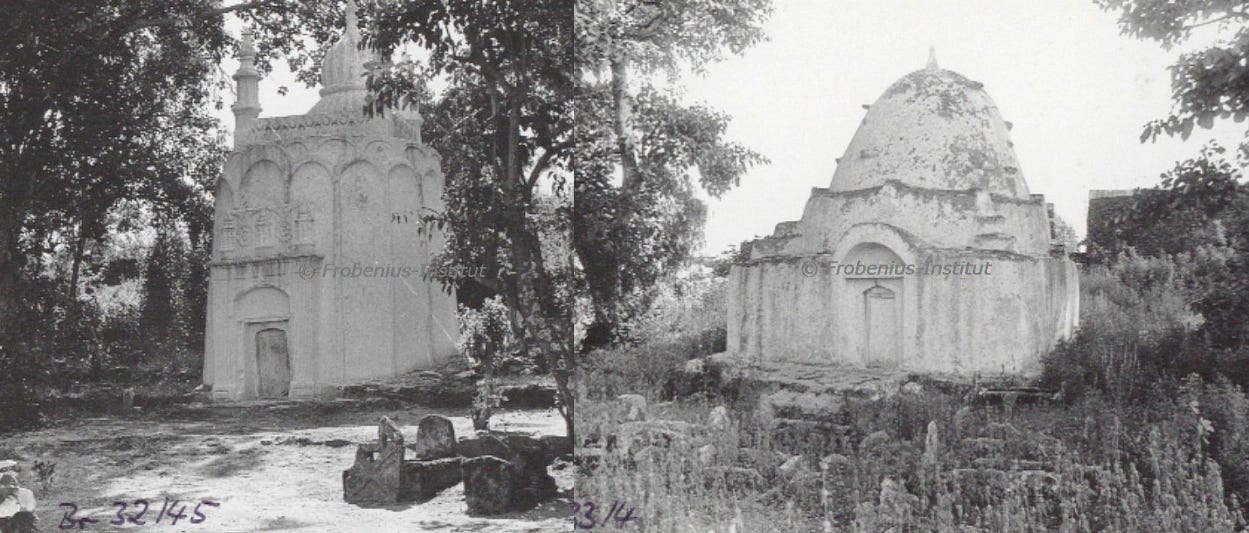

These structures were similar to the more numerous shrines of Harar and central Eritrea, which are typically domed structures of wood and stone of multiple sizes that were often plastered with lime and protected by a perimeter wall of stone. In Bale, the most important of these is the shrine of Shaykh Ḥusayn, while in Wallo, the main pilgrimage site was the shrine of Jama Negus to the south of Kombolcha in Ahmara.24

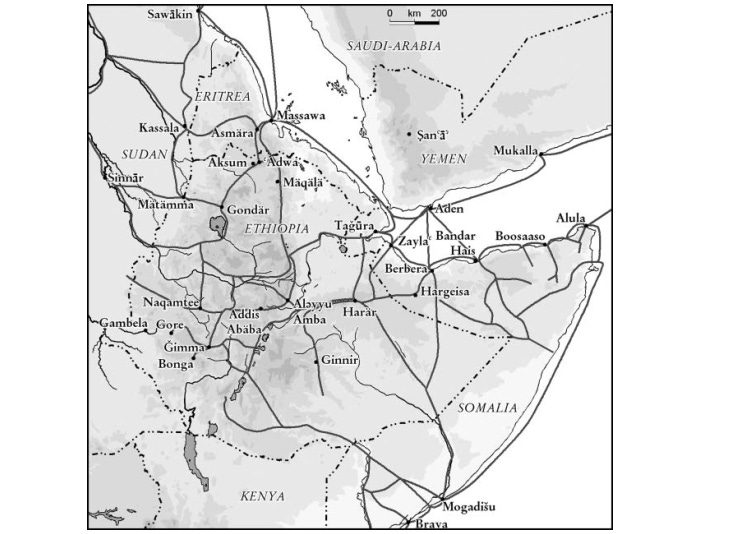

Trade routes in the Middle and Early Modern Ages. Map by R. Pankhurst

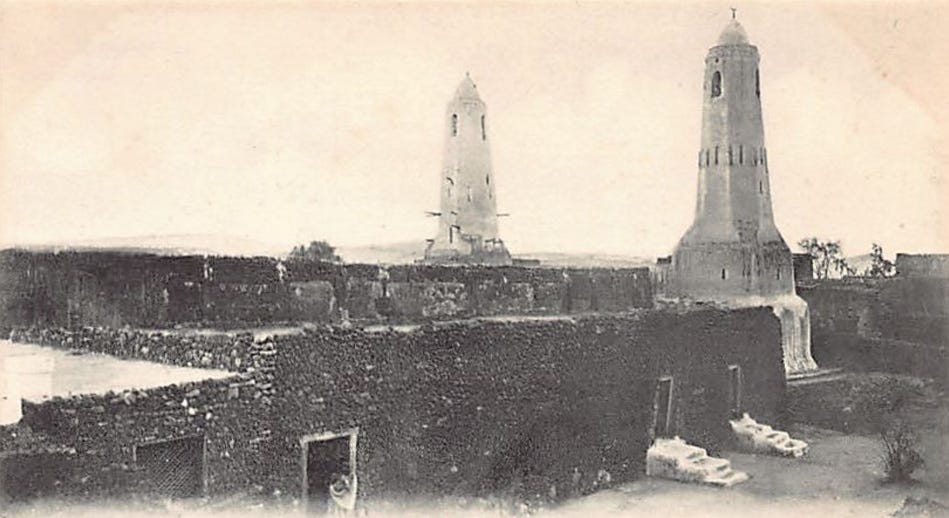

The Jami mosque of Harar in the late 19th century, before its renovation

Saints’ shrines in Harar, Ethiopia, ca. 1972. Frobenius institute

Old tombs in the vicinity of Keren, Eritrea. ca. 1943. Bristol archives

Old buildings in Massawa, Eritrea. ca. 1918. Archiviofotografico, societageografica, Italy. The structure on the left may be the shrine below.

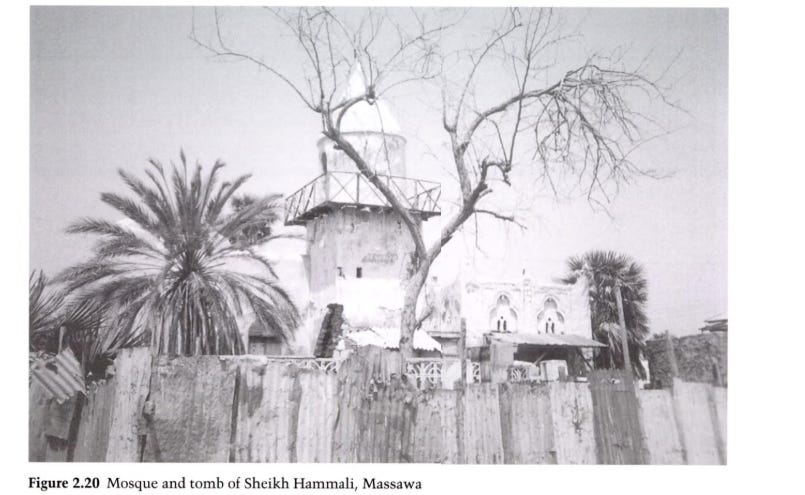

Mosque and tomb of Sheikh Hammali, Massawa, Eritrea. Image by T. Insoll. The structure was built in the second half of the 16th century.

The Shrine of Shaykh Ḥusayn. Gololcha, Bale, Oromia region, Ethiopia. Image by Terje Østebø.

Architecture in 19th-century Ethiopia: The contributions of local and foreign masons

The city of Gondar became a point of diffusion for its unique style of architecture across other parts of the country. The Betä Ésraýel played a major role in the spread of this architectural style, emerging as a professional class of masons.

Their chief employment, according to the early 19th-century visitor Henry Salt, consisted in “building and thatching houses,” and their skill in these fields was “most to be admired.” Betä Ésraýel house-builders worked, according to William Coffin, for one Maria Theresa thaler per six-day week, while a thatcher would complete a roof for a piece-rate of four thalers. The extent of Betä Ésraýel building activity was also emphasised by subsequent observers, such as Walter Plowden, who termed them “the best masons in the country,” and Henry Dufton, who later went so far as to affirm that “all the builders and artisans” were Betä Ésraýel.25

The combined use of foreign and local artisans was revived in the late 19th century by Yohannes IV and Menelik II. The former commissioned the construction of a castle at Mekelle, which was built in the 1880s by a local team of masons supervised by an Italian carpenter. It is a two-storey structure containing multiple rooms, a banqueting hall with rows of pillars, as well as castellated turrets and parapets.26

Menelik employed Indian masons in the construction of the church of Ragu’el at Entoto, built in 1883, and the church of Maryam at Addis Alam, built in 1902. He later used Italian workmen captured from the defeat at Adwa of 1896 to build several structures, including St. George’s Cathedral in Addis Ababa, and Ras Makonnen’s Palace in Harar. In the 1870s, the Oromo king Abba Jifar II had also erected a large palace at his capital of Jimma, in the Oromia region, whose construction was supervised by an Indian mason.27

Besides these few monuments, most structures would have been built by local masons. Internal accounts mention how craftsmen from Gondar were so well regarded that King Sahla Sellase of Shewa, when erecting the church of Madhane ‘Alam at Ankober, sent for carpenters from the old city. Half a century later, a master carpenter from the city was sent to Shewa with nine assistants who were employed by Menelik in constructing his palace at Entoto.28

The chronicles of Ethiopia include the names of several of these Ethiopian ‘master carpenters’ since the 17th century, whose position was analogous to that of a ‘head mason’ or ‘architect’. Menelik and Taytu commissioned the construction of several churches and royal residences using local masons, especially in the city of Addis Ababa, which was founded in 1887.29

The city became the country’s capital in 1889, and quickly attracted a diverse population that included artisans, merchants, and foreign visitors, whose diverse architectural styles laid the foundation for some of the modern styles of construction seen across the country today.

Yohannes’ castle at Mekelle, Tigray, Ethiopia. ca. 1935.

Menelik’s palace. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Aba Jifar’s palace at Jimma. Oromia region, Ethiopia.

Mariam church on Entoto mountain, Ethiopia, ca. 1928-1929. USCL

Modern architecture in the city of Dire Dawa, Ethiopia. ca. 1934

Equestrian statue of Menelik II, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 1931.

The renovated palace of Menelik II.

During the late Middle Ages, a network of cities and towns dotted the central regions of Eritrea, which linked the western Indian Ocean world to the mainland region of Ethiopia.

The history of the medieval cities and towns of Eritrea is the subject of my latest Patreon article. Please subscribe to read more about it here and support this newsletter:

The Development of Ancient States in the Northern Horn of Africa, c. 3000 BC–AD 1000: An Archaeological Outline by Rodolfo Fattovich, pg 154-156, Tallies, Tokens & Counters: An Introduction by Anna Maria D’Onofrio, pg 51-52

Eastern Sudan in its Setting: The archaeology of a region far from the Nile Valley by Andrea Manzo, pg 38-39

Changing Settlement Patterns in the Aksum-Yeha Region of Ethiopia: 700 BC - AD 850 by Joseph W. Michels, What was the South Arabian Impact on the Development of Ethiopian Margins in Antiquity by Anne Benoist et al.

Remarks on the pre-Aksumite period in Northern Ethiopia by Rodolfo Fattovich, The First Millennium BC in the Highlands of Northern Ethiopia and South-Central Eritrea: A Reassessment of Cultural and Political Development by David W. Phillipson

Urban Precursors in the Horn: Early 1st-millennium BC communities in Eritrea by P. Schmidt and M. Curtis, Relating the Ancient Ona Culture to the Wider Northern Horn: Discerning Patterns and Problems in the Archaeology of the First Millennium BC by Matthew C. Curtis

Ancient Churches of Ethiopia: Fourth to Fourteenth Centuries by D. W. Phillipson, pg 32-35, Changing Settlement Patterns in the Aksum-Yeha Region of Ethiopia: 700 BC - AD 850 by Joseph W. Michels, pg 69-72, The First Millennium BC in the Highlands of Northern Ethiopia and South-Central Eritrea: A Reassessment of Cultural and Political Development by David W. Phillipson, pg 265-266. The Almaqah temple of Wukro in Tigrai/Ethiopia by Pawel Wolf et. al

Encyclopedia Aethiopica, Vol. 1, edited by Siegbert Uhlig, pg 323, Foundations of an African Civilisation by D. W Phillipson, pg 121-123

What was the South Arabian Impact on the Development of Ethiopian Margins in Antiquity by Anne Benoist et al. Foundations of an African Civilisation by D. W Phillipson, pg 125

An archaeology of conversion? Evidence from Adulis for early Christianity and religious transition in the Horn of Africa by Gabriele Castiglia. Ancient Churches of Ethiopia: Fourth to Fourteenth Centuries by D. W. Phillipson, pg 37-45

Ancient Churches of Ethiopia: Fourth to Fourteenth Centuries by D. W. Phillipson, 46-74

Foundations of an African Civilisation: Aksum and the Northern Horn by D. W Phillipson, pg 212-223, 229-242, Rock-cut stratigraphy: sequencing the Lalibela churches by Francois-Xavier Fauvelle-Aymar, The rock-cut churches of Lalibela and the cave church of Washa Mika’el by Marie-Laure Derat

Encyclopedia Aethiopica, Vol. 3, edited by Siegbert Uhlig, pg 765-767

La culture Shay d’Éthiopie (Xe-XIVe siècles) by François-Xavier Fauvelle-Aymar, The archaeology of complexity and cosmopolitanism in medieval Ethiopia by Timothy Insoll, pg 461

Localising Salafism: Religious Change among Oromo Muslims in Bale, Ethiopia By Terje Østebø, pg 45-58. A History of Derbé Belanbel Historical and Cultural Site by Wagaw Bogale. Megalithic heritage sites of Ethiopia: the case of Derbi Belanbel Steles in the Somali region by Tesfamichael Teshale

The Oxford Handbook of Islamic Archaeology edited by Bethany J. Walker, Timothy Insoll, Corisande Fenwick, pg 423-435. Le sultanat de l’Awfāt, sa capitale et la nécropole des Walasma by François-Xavier Fauvelle, Notes on the survey of Islamic Archaeological sites in South-Eastern Wallo (Ethiopia). Historic Mosques in Sub-Saharan Africa: From Timbuktu to Zanzibar By Stéphane Pradines, pg 116-129

“The habitations are mostly long, flat-roofed shes, double storied, with doors composed of a single plank, and holes for windows pierced high above the ground. the poorest classes inhabit Gambisa the thatched cottages of the hill cultivators.”

First Footsteps in East Africa, Or: An Exploration of Harar, by Richard Francis Burton

Medieval Ethiopian Kingship, Craft, and Diplomacy with Latin Europe By Verena Krebs, pg 193-214. Day Giyorgis by S. Chojnacki. Enselalé, avec d’autres sites du Choa, de l’Arssi, et un îlot du lac Tana by Francis Anfray

The Archaeology of the Jesuit Missions in Ethiopia (1557–1632) by Víctor Manuel Fernández. A Social History of Ethiopia: The Northern and Central Highlands from Early Medieval Times to the Rise of Emperor Téwodros II by Richard Pankhurst, pg 105

The Archaeology of the Jesuit Missions in Ethiopia (1557–1632) by Víctor Manuel Fernández, pg 75, 135, Encyclopedia Aethiopica, Vol. 2, edited by Siegbert Uhlig, pg 845

Encyclopedia Aethiopica, Vol. 2, edited by Siegbert Uhlig, pg 843-844

A Social History of Ethiopia: The Northern and Central Highlands from Early Medieval Times to the Rise of Emperor Téwodros II by Richard Pankhurst, pg 106. The Ethiopian Royal Chronicles by Richard Pankhurst, pg 124

A Social History of Ethiopia: The Northern and Central Highlands from Early Medieval Times to the Rise of Emperor Téwodros II by Richard Pankhurst, pg 105-109

Encyclopedia Aethiopica, Vol. 1, edited by Siegbert Uhlig, pg 325-326

Localising Salafism: Religious Change among Oromo Muslims in Bale, Ethiopia by Terje Østebø, pg 66-77. Islam in Nineteenth-Century Wallo, Ethiopia: Revival, Reform and Reaction by Hussein Ahmed, pg 83-91. Islamic History and Culture in Southern Ethiopia: Collected Essays by Ulrich Braukämper, pg 113-123

A Social History of Ethiopia: The Northern and Central Highlands from Early Medieval Times to the Rise of Emperor Téwodros II by Richard Pankhurst pg 233)

Historical orientation of Yohannes IV Palace in Mekelle, Tigray State, Ethiopia, from the aspects of planning and building techniques by Nobuhiro Shimizu and Alula Tesfay Asfha

The Role of Indian Craftsmen in Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth-Century Ethiopian Palace, Church and Other Buildings by Richard Pankhurst, pg 11-20. Heritages and their conservation in the Gibe region (Southwest Ethiopia): a history, ca. 1800-1980 by Nejib Raya, pg 73-77

A Social History of Ethiopia: The Northern and Central Highlands from Early Medieval Times to the Rise of Emperor Téwodros II by Richard Pankhurst pg 232)

The Ethiopian Royal Chronicles by Richard Pankhurst, pg 168-171, Menelik and the Utilisation of Foreign Skills in Ethiopia by Richard Pankhurst

Fascinating...

Amazing compilation tbh. Only thing I noticed is the Tartar Gur tumulus is actually in Menz/Shewa rather than South Wollo. But there is shay Tumuli in both regions though