The intellectual history of East Africa (ca. 900-1950 CE): from the Swahili coast to Buganda to Eastern Congo.

The intellectual history of pre-colonial Africa is dominated by studies of the scholarly traditions of Ethiopia, West Africa, and Sudan, where a large corpus of extant manuscripts have been collected from the old scholarly centers of Timbuktu, Djenne, Gondar, and Harar.

However, recent discoveries of manuscript collections across East Africa have attracted significant interest in the region’s intellectual traditions, and the scholarly networks that produced these remarkable works of pre-colonial African literature, that extended from the Swahili coast to the interior kingdoms of Buganda and the eastern D.R.Congo.

This article explores the intellectual history of East Africa, focusing on the region’s education systems and scholarly networks during the pre-colonial and early colonial periods.

The intellectual history of the East African coast.

Map of the Swahili city-states

The intellectual history of East Africa began with the region’s gradual integration into the cultural and commercial exchanges of the Indian Ocean world that occurred in the cosmopolitan cities of the coast. In the Swahili-speaking populations of these urban communities, Islam was adopted and internalized into the cultural and political traditions of the coast, resulting in the creation of distinctively local practices and material culture.1

Inscribed coins and architectural fragments dated to between the 9th and 12th centuries appear at Shanga, Zanzibar, and Barawa, which were likely commissioned by local elites. Swahili names written in the Arabic script (ie; Ajami) appear as early as the 14th century on inscriptions recovered from the cities of Kilwa and Mombasa. Their stylistic similarities to later manuscript designs and calligraphy, provide early and continuous evidence for writing along the East African coast.2

Epitaph of Sayyida Aisha bint Mawlana Amir Ali b. Mawlana Sultan Sulayman, c. 1360, Kilwa, Epitaph of 'Mwana wa Bwana binti mwidani' , c. 1462, Kilindini, Mombasa.

According to the account of Ibn Battuta, who visited the region in 1331, the court entourage of the rulers of Mogadishu and Kilwa included qadis, wazirs, lawyers, secretaries, sharifs, shaikhs "and those who have made the pilgrimage". He adds that the ruler of Kilwa, who traveled to Mecca according to the 16th-century Kilwa chronicle, was known for his veneration of ‘holy men’ who frequented his court from as far away as the Hijaz and Iraq. Mogadishu achieved an early reputation as a center of learning, and Ibn Battuta reported that many "lawyers" resided there, where disputes were settled by qadis.3

It is likely that significant numbers of Swahili scholars were already traveling across the western Indian Ocean before the pilgrimage of the King of Kilwa, as evidenced by references to sailors and merchants from Kilwa, Barawa, and Mogadishu who traveled to the ports of Yemen during the 13th and 14th centuries. 4 The 15th-century Mamluk-Egyptian chronicler Al-Maqrizi for example, met with an unnamed qadi from the city of Lamu. According to al-Maqrizi, the qadi was “a man of great erudition in the law according to the Shafi i rite.” By the 14th-15th century, most Swahili scholars adhered to the Shafi'i school of Islamic jurisprudence.5

By the end of the Middle Ages, a vibrant intellectual tradition had emerged across many of the large Swahili cities and towns. Recent discoveries of old Qur'anic manuscripts from Lamu dated to the 15th century and the written correspondence between Swahili rulers and Portuguese interlopers in the 16th century, corroborate textual and archaeological evidence for the early emergence of the Swahili manuscript traditions, which were significantly older than the previously known manuscripts from the 17th century.6

A recently discovered Quran with a date of 1410 AD (813 A.H), from Pate, Lamu archipelago, private collection (image from Nation media)

letters written by Swahili rulers addressed to the Portuguese ruler Dom Manuel (r. 1495-1521), from; Sultan Ibrahim of Kilwa in 1505, Sultan Ali bin Ali of Malindi in 1520, Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, Lisbon

Beginning in the 17th century on the Lamu archipelago, an intellectual revolution across the East African coast resulted in the production of a significant volume of literature by local scholars. In particular, the city-state of Pate became a major scholarly center attracting scholarly diasporas such as the Alawi tariqa of the Hadhramaut. Swahili and other East African scholars created the oldest known documents during this period, most of which belonged to a unique genre of poetry known as Utendi/Utenzi.7

These scholars include; Aydarus b. Uthman, who wrote the Utendi wa Hamziyya in 1749; his kinsman Sayyid Abd Allah (c. 1720–1820) who composed the philosophical work titled Al-Inkishafi in 1800; the 18th century Pate scholar Bwana Mwengo, who wrote the Utendi wa Herekali, his son Abubakar Mwengo, who wrote the Utendi wa Katirifu and Utendi wa Fatuma in the early 19th century, and the Siyu queen Mwana Kupona bint Msham (d.1860) who wrote the Utendi wa Mwana Kupona.8

Al-Inkishafi (MS 373), likely copied in the 19th century, images by SOAS library

Bwana Mwengo's Utendi wa Herekali, copied by Muhamadi Kijuma, images by SOAS London

While a few of these scholars also held political power, for most of Swahili history, scholars only served in advisory capacities while adjudication was left to the rulers. This changed when the East African coast gradually came under the control of the Oman Sultans; Sayyids Said (1832-56), Majid (1856-70), and Barghash (1870-88) who established their capital at Zanzibar. These sultans delegated adjudication to court-appointed qadis by appointing two official court qadis, one Ibadi, for their Omani subjects, and one Shafi'i, for the Swahili majority.9

During the 19th century, Zanzibar became the new focal point of intellectual life along the coast, partly fuelled by the rapid expansion of commodities trade with the mainland, especially ivory, whose prices rose as the frontier expanded inland. The city attracted some of the best scholars of Mombasa, Lamu, Comoros, and Barawe, who brought with them sufi tariqas (orders) such as the Qadiriyya and the Shadhiliyya. Unlike the established scholarly community of the Swahili coast which reserved education for elite families, the scholars trained by these orders came from across the entire society.10

The most noteworthy include; the Barawa scholar Shaykh Uways al-Qadiri, the Bagamoyo scholar Shaykh Yahya b. Abdallah, the Siyu scholar Sayyid 'Abdur-Rahman b. Ahmad al-Saqqaf, and the Lamu scholar Habib Salih b.Alawi Jamal al-Layl. Scholars like Shaykh Uways, through their efforts to spread the teachings of their tariqa, directly contributed to the emergence of several intellectual traditions on the East African mainland during the second half of the 19th century, which were brought by the ivory caravans and itinerant teachers to places as distant as Buganda and the Eastern D.R.Congo.11

The intellectual history of the kingdom of Buganda.

Map showing the kingdoms of East Africa’s Great Lakes region and the 19th century caravan routes.

Coastal traders reached the kingdom of Buganda near the end of the reign of its King (Kabaka) Suna (r. 1832-56), who reportedly held discussions with the caravan leader Ahmad bin Ibrahim (Medi Ibulaimu) on theology and law.12 Suna kept a small library that he gave to his successor, Kabaka Muteesa, which included a “voluminous Arab manuscript worn and discoloured by age” that was seen by later visitors to the kingdom in 187613. Later coastal traders who reached Buganda in 1867, such as the Swahili and Comorian merchants Choli and Idi served as teachers of Muteesa. The latter quickly learned Arabic and Swahili, translated sections of the Quran into Luganda, and encouraged the construction of mosques and schools throughout his kingdom.14

By the 1870s, Muteesa was able to send Ganda envoys who were literate in Arabic and Swahili, to Zanzibar, to the Khedive's government in Khartoum (Sudan), and to England. A visitor to Buganda in 1875 wrote of Mtesa’s court: “Nearly all the principal attendants at the court can write the Arabic letters. The Emperor and many of the chiefs both read and write that character with facility, and frequently employ it to send messages to another, or to strangers at a distance.”15

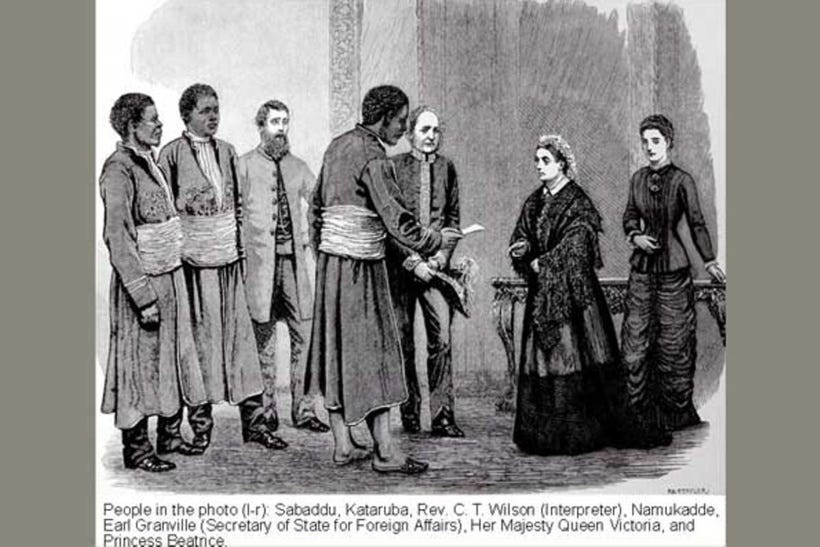

Buganda’s embassy to Queen Victoria in London, ca. 1880. Illustration taken from ‘The Church Missionary Gleaner, Volume II, 1880.’ The envoys presented a letter written by Muteesa.

While most of the coastal traders in Buganda were not interested in teaching, a significant learned community (Ulama) of baGanda Muslims had emerged by the end of Mtesa's reign and the early reign of his successor, Kabaka Mwanga (r. 1884-1888). The simultaneous emergence of baGanda Christian courtiers trained in mission schools, and Mwanga’s inability to control the centrifugal forces of the kingdom, led to his overthrow by both parties in September 1888. He was replaced by the short-lived kings; Kiweewa and Kalema, who ruled until Mwanga was restored by the Christian faction in 1889.16

Mwanga’s return led to the loss of influence of the kingdom's Ulama, and their emigration to neighboring areas such as the kingdom of Ankole. Mosques and schools were taken over by the Christian faction, and powerful courtiers like Ham Mukasa (1870-1956) and Stanislaus Mugwanya whose early education was in Swahili and Arabic, switched to writing in the Latin script,17 such as Ham Mukasa’s 1902 publication documenting his journey to England. While Muteesa and his courtiers were known to have composed letters in Swahili and Arabic, and kept Arabic manuscripts,18 none of the early writings by Buganda’s Ulama from the late 19th century have been recovered.

Many of the emigres became the first Ulama in those regions and some took up administrative positions during the early colonial period. However, their numbers remained small compared to Buganda, whose Ulama had recovered by early 20th century, and adopted East African-derived traditions such as the Maulid celebrations. Some scholars, such as Hajji Sekimwanyi, also undertook the pilgrimage to mecca, and published a travel account of his journey to the Hijaz in 1920.19

The oldest surviving documents written by Buganda’s Ulama were books published by local printing presses in the early 20th century.20 Many of the published accounts are concerned with historiography, they include; Sheikh Abdul Karim Nyanzi's ‘Ebyafayo Bye Ntalo Ze Ddini Mu Buganda’ (History of the Wars of Religion); Bakale Mukasa bin Mayanja’s ‘Akatabo k’Ebyafayo Ebyantalo’ in 1932, (An Introduction to the History of the Wars)21, Hajji Sekimwanyi's ‘Ebyafayo B'yobuisiramu mu Buganda’ in 1947 (History of Islam in Buganda). and several others, some of which are in manuscript form.22

A handful of external scholars also began to arrive in Buganda during the early 20th century. These include the Bornu* scholar Shaykh Hajji Muhammad Abdallah, who in the 1890s, traveled from Nigeria to Mecca, before traveling through Egypt, Ethiopia, Somaliland, and Kenya, after which he moved to Bombo, near Kampala, in 1905. He played a role in establishing a school and mosque at Bombo, and mostly stayed in Uganda until his death in 1943.23 Others include Khlafan Ibn Mubaraka and Abd al-Samad ibn Najimi who also trained many bawalimu (teachers) in Buganda.24

The Masjid Noor and the tombs of Shaykh Hajji Muhammad and others at Bombo, Luwero, Uganda. Image by Author. The original mosque was constructed in 192025 and expanded in the 1970s.

The intellectual history of the eastern D.R.Congo.

Map of the Democratic Republic of Congo, showing Maniema Province and the location of Kasongo, Nyangwe and Boyoma Falls. image by Noemie Arazi et al.

Coastal traders reached the region of Eastern D.R. Congo during the mid-19th century. While they were referred to as the 'Waungwana' (Swahili term for patrician), they were a diverse group that included Omani, Comorian and Swahili merchants.26 They were driven into the interior by the expanding ivory frontier and the commodities trade, establishing towns and trading stations such as Kasongo, Kabambare, and Nyangwe.27

A few of them, such as Tippo Tip (Ḥamad al-Murjabī), Rumaliza, and the Comorian merchant Kibonge, gradually acquired more power through their commercial networks and political alliances. The capitals of their new states became important centers of learning for the region's small but growing Muslim community. Schools were established at Kasongo and Nywangwe, scribes literate in both Swahili and Arabic were employed by most local rulers to correspond with each other (and later with the Belgian colonists), and the bawalimu (teachers/scholars) also wrote copies of Islamic works as well as amulets that were in high demand among neighboring groups.28

19th-century Swahili documents from the eastern D.R.Congo at the Africa Museum in Tervuren, Belgium. Images from Wikimedia Commons.

The earliest among the known Congolese documents in Arabic script, available in various museums and archives in Belgium, all date from the late 19th century and consist, among others, of Swahili treatises, astrological manuscripts, letters in Arabic and Swahili, prayer books, and inscribed objects. All were written by local scribes, the known authors of whom include; Shanzī bin Jum‘a, the Comorian clerk of Rashid bin Muhammed, who was Tippu Tip’s nephew; Sa‘īd bin ‘Īsa, a relative of Rumaliza, and Fundi Lubangi, a Swahili clerk who later worked for European officers.29

Like in Buganda, the significance of the scholarly communities of eastern D.R.Congo established during the pre-colonial era becomes evident during the colonial period, when they expanded and took on added importance. By the time of the First World War, the Ulama of East Africa existed in or near most colonial administrative centers. Most of these communities inherited the dominant attributes of Swahili intellectual and religious traditions (such as the Shafi'i school of law), and they came to exhibit common underlying characteristics derived from Swahili coastal culture, such as mosque architecture.30

Ruins of a mosque in Isangi, eastern D.R.Congo, ca. 1894. NMVW.

The education system and curriculum of pre-colonial East Africa.

The schools established on the East African coast and the mainland during the pre-colonial period offered basic education to anyone who desired it, and most Ulama offered advanced learning in some specialized science. The quality of advanced education also benefitted from itinerant scholars like Ali b. 'Abdallah Mazru'i and Sh. 'Abdallah Bakathir, who traveled to the Hijaz. The texts that were taught were mostly standard Shafi'i legal and theological works that formed part of the “Indian Ocean corpus,” some of which were composed by local scholars. For example; Muhyi ad-Din composed works on theology and morphology, as well as a commentary on Nawawi's Minhaj al-Talibin. while the writings of Abdul-Aziz b. Abdul-Ghani, dealt with a variety of subjects, including theology, grammar, and rhetoric.31

Like in West Africa, the education system of East Africa was centered around individual scholars rather than institutions. According to Mtoro Bakari’s detailed ethnographic account of the Swahili written in 1903, “Some sheikhs teach in their houses and some in the mosques,” a teacher (mwalimu) chooses which subject to teach their students and for how long, the student’s family pays the teacher while the student brings the materials such as writing boards and ink. Advanced learning (Elimu = Knowledge) begins around the age of 20 when students are taught; legal works such as the Min haj [ Min Haj at-Talibin, of An-Nawawt (d. 1277), a well-known textbook of Shafi'i law]; laws on commerce, marriage and divorce; works on grammar and commentaries.32

the Sharh tarbiyyat al-atfal (expounding on the Instruction for children) written in 1842 in Zanzibar by the Barawa-born scholar Muhyi al-Qahtani (ca. 1790-1869), Riyadha Mosque, Lamu, Kenya.

An account from 1909 describing the books taught in the schools of Kisangani in eastern D.R.Congo, notes that “all the written customs, specific to the Banguana, are called Uaguana and are divided in four books: the Morahabahti, the Shamtilimanfi, the Kitabutchanusai and the Kazel Kule. They write them in the Swahili language with the help of the Arabic letters.” adding that there are also works of juridical nature, refered to as “copies of successive Kanuni” and that “The only way to get to know them is to have gained the absolute confidence of a learned leader”33

Like in most parts of the Islamic world, students in East Africa were instructed from the personal libraries of individual teachers and after completing their studies, were elevated to the status of ‘Shaykh’ and issued an ijazah (whether oral or written) authorizing them to teach a given subject. This system is attested in Buganda34 and in Eastern D.R.Congo.

According to the 1909 description of schools in eastern D.R. Congo: “In Kisangani, the ‘village arabisé’ of Stanleyville, lives a great mwalimu. This mwalimu is […] the one who’s in charge of teaching the children how to write. He is accompanied by a man almost as learned as he is […]. The two men are assisted by 18 teachers who depend on them and follow their instructions […]. They write them in the Swahili language with the Arabic alphabet.”35

While the shaykhs of elite coastal families only offered advanced learning to other elites, students who received their education from the tariqas such as those who were taught by the Barawa Shaykh Uways and his students managed to get some degree of advanced education. A description of the extent of writing in Kisangani from the 1909 account notes that, “We can affirm that all the Africans who follow the [mwalimu’s] teaching and have adopted Islam are able to write and read Swahili, often very purely”36

the Alfyya [The One Thousand, verse of 1000 lines] copied in Lamu by Shārū al-Sūmālī in 1858, Riyadha Mosque, Lamu, Kenya.37

Trans-regional intellectual networks in East Africa: the biography of Uways al-Barawi. (1847-1909)

Uways b. Mohamed, better known as Sheikh/Shaykh Uways al-Qādirī was born in the old town of Barawa in 1847. Unlike most established scholars of the old city, he belonged to a family of humble origins of the Goigal lineage who were clients of the Tunni-Somali clan, and the family earned their livelihood primarily as weavers.38

Shaykh Uways’s first teachers were the local scholars in Barawa such as Shaykh Muḥammad Jannah al-Bahlūlī, Shaykh Aḥmad Jabhad, and Shaykh Muḥammad Ṭaʾyīnī, the latter of whom encouraged Uways to join the Qādiriyyah order and travel abroad to learn under its scholars in Iraq. In 1870 Shaykh Uways travelled to Baghdad where he studied under Sayyid al-Kilānī, a descendant of Shaykh ʿAbdulqādir al-Jīlānī, the founder of the Qādiriyyah, and eventually obtained his full authorization (ijāzah) to teach. He also performed his first pilgrimage to Mecca in 1873 and later traveled back to Baghdad, only returning to Barawa in 1882, where he attracted a large following.39

Shaykh Uways mainly led a peripatetic life, moving with his entourage from Somalia to Arabia to Zanzibar; where the sultans; Bargash, Khalifa and Hamid offered him financial assistance and residencies for his followers.40 He composed several didactic poems in Somali, Arabic and in Chimiini-Swahili, thus spreading his branch of the Qadiriyyah (called the Qadiriyyah Uwaysiyyah) across Somalia; Zanzibar; Comoros; Tanzania; eastern D.R.Congo, and as far as Yemen and Java.41

According to a hagiography of him written by the Barawa scholar Qassim al-Barawī’ in 1917, Shaykh Uways had more than 150 deputies (khalīfas) of many different backgrounds including the Zanzibar sultans Barghash and Khalīfa. Unlike his coastal peers, Uways and his followers taught everyone; "men, women, and children, slave and free."42

A poem by Shaykh Uways, image from banadirwiki.

The Qādiriyya thus quickly spread through the khalīfas appointed by him, beginning with his fellow Brawa-born scholars in Zanzibar such as ShaykhʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Amawī (1838–1896) and Sayyid ʿUmar Qullatayn (d. 1926), to Comorians like Mkelle b. Adam (b. 1855) and ʿĪsā b. Aḥmad al-Injazījī who spread it to Mozambique, and then to mainlanders like Shaykh Mjana kheri (b. 1870) who spread it across Tanzania, Malawi, and even Congo. These scholars all established zawiyas (sufi institutions) and schools for educational purposes, they awarded ijazahs (certificates), whose isnads (chains of transmission) went back directly to Shaykh Uways.43

Historians argue that Shaykh Uways’ unlikely collaboration with the Zanzibar Sultan Bargash (who was a strict Ibadi) was primarily political; as both wanted to expel the Europeans from the East African mainland by leveraging their extensive scholarly network in the interior. This is evidenced by the active participation of the Zanzibar scholar Sulayman bin Zahir al-Jabir al-Barawi in the overthrow of the Buganda king Mwanga in 1888. Sulayman al-Barawi was a close fried and likely emissary of Sultan Bargash. He was also a leading member of the Qadiriyya in Buganda and aided the ascendancy of Buganda’s Ulama in the kingdom’s court politics until his departure in late 1888.44

In the succeeding decades, the Qadiriyya of East Africa was at the forefront of the anti-colonial movement in many societies opposed to the German presence in Tanzania. This movement culminated in the rebellions of 1905-1908 when various anti-colonial letters authored by Qadiriyya Khalifas like Zahir al-Barawi in Tabora and Rumaliza in Zanzibar (after moving from eastern D.R.congo), were spread across southern and central Tanzania, urging the Ulama and their followers to rise up against the Germans. Occurring shortly after the Maji Maji uprising, this rebellion alarmed the Germans who moved swiftly against it, arresting several of its leaders and forcing some into exile.45

Despite his political sympathies for this anti-colonial movement, Shaykh Uways never clashed directly with colonial authorities in Zanzibar or Somalia, unlike his later opponent; Muḥammad ibn Abdallah Ḥasan of Somalia (Mad Mullah), who waged a 20-year-long anti-colonial war against the British, Italians and Ethiopians. Affiliated with the Wahhabis of Arabia, Sayyid Muḥammad was opposed to the Qādirīyyah order of Shaykh Uways. After a series of virulent exchanges in verse between the heads of the two movements, the dispute escalated to actual fighting, ending with the assassination of Shaykh Uways in 1909 by a group of Sayyid Muḥammad’s followers at Biolay, 150 miles north of Barawa.46

The old town of Barawa, Somalia. in the mid-20th century.

Shaykh Uways’ popularity increased after his death, both in the colonial and post-independence periods. In Rwanda and Burundi, and throughout the Congo-Tanzanian border region, the Qadiriyya is referred to as the 'Mulidi' or 'Muridi'. In Kisangani, it was introduced by the Comorian scholar Ḥabīb bin Aḥmad who reached the town in 1904, while in Burundi, it was introduced by ‘Abd al-Raḥman at the lake-shore town of Rumonge, albeit relatively late in the 1950s. The connections of these Qadiriyya scholars to Uways are indicated by their chains of transmission, attesting to the extended reach of the intellectual traditions of East Africa.47

While studies of the intellectual history of East Africa are still in their infancy, the available research on the scholarly traditions of the Swahili coast, and the mainland regions of Buganda and eastern D.R.Congo attest to the rapid spread of writing across the region during the late 19th century. The scholars who composed these little-known manuscripts played a significant role in the historical developments of the region and can greatly expand our understanding of Africa’s rich but often overlooked intellectual history.

19th-century Astronomical manuscript from Lamu, Kenya.48

The Swahili scholar Mtoro Bakari (1869-1927) who is cited in the above essay was one of the founders of African Studies in Europe, and one of the first Africans to publish their academic research on African societies. Unfortunately, Mtoro’s groundbreaking research was overshadowed by his peers in Germany, where he taught as a lecturer at the universities of Berlin and Hamburg from 1900-1913.

Read more about the fascinating life and works of Mtoro Bakari in my latest Patreon article here:

The History of Islam in Africa edited by Nehemia Levtzion, Randall L. Pouwels pg 254-256

Writing in Swahili on Stone and on Paper by Ann Biersteker pg 15-25

The East African Coast: Select Documents from the First to the Earlier Nineteenth Century. by Greville S. P. Freeman-Grenville pg 29-32, 38-39

13th century Persian sources: A Traveller in Thirteenth-century Arabia: Ibn Al-Mujāwir's Tārīkh Al-mustabṣir by Yūsuf ibn Yaʻqūb Ibn al-Mujāwir pg 151, 165. 14th century Rasulid-Yemen sources: L’Arabie marchande, : État et commerce sous les sultans rasūlides du Yémen (626-858/1229-1454) by Éric Vallet, Chapter9, par. 29-31.

The East African Coast: Select Documents from the First to the Earlier Nineteenth Century. by Greville S. P. Freeman-Grenville pg 33)

Writing in Swahili on Stone and on Paper by Ann Biersteker pg 13-14)

Swahili Literature and History in the Post-Structuralist Era by Randall L. Pouwels pg 272-283, On the poetics of the Utendi by Clarissa Vierke pg 19-21

Sufis and scholars of the sea by Anne K. Bang pg 30-31,Islam and the Heroic Image by John Renard pg 246-247, Epic Poetry in Swahili by Jan Knappert pg 51-52, On the Poetics of the Utendi by Clarissa Vierke pg 440

The History of Islam in Africa edited by Nehemia Levtzion, Randall L. Pouwels pg 262)

Muslim Brotherhoods in Nineteenth-Century Africa By B. G. Martin pg 152-177, The History of Islam in Africa edited by Nehemia Levtzion, Randall L. Pouwels pg 263)

The History of Islam in Africa edited by Nehemia Levtzion, Randall L. Pouwels pg 264-265)

The History of Islam in Africa edited by Nehemia Levtzion, Randall L. Pouwels pg 291-292) Colonial Buganda and the End of Empire: Political Thought and Historical Imagination in Africa by Jonathon L. Earle pg 143

Central Africa: Naked Truths of Naked People: An Account of Expeditions to the Lake Victoria Nyanza and the Makraka Niam-Niam, West of the Bahr-el-Abiad (White Nile). by Charles Chaillé-Long, pg 121

The Arab and Islamic Impact on Buganda during the Reign of Kabaka Mutesa by Oded Arye pg 119-223

The Arab and Islamic Impact on Buganda during the Reign of Kabaka Mutesa by Oded Arye pg 220, 224, Through the Dark Continent, Or, The Sources of the Nile Around the Great Lakes of Equatorial Africa and Down the Livingstone River to the Atlantic Ocean, Volume 1 by Henry Morton Stanley 322

Fabrication of Empire by Anthony Low pg 52-53, 65-66

Ham Mukasa’s autobiography; The Wonderful Story of Uganda by Joseph Dennis Mullins, Ham Mukasa pg 176-178, 182-183, The Uganda Journal, Volumes 33-35: Luganda Historical writing by John Lowe 1893-1969, pg 19

Colonial Buganda and the End of Empire: Political Thought and Historical Imagination in Africa by Jonathon L. Earle pg 144-146

The Spread of Islam in Uganda by A. B. K. Kasozi pg 152, 175-178, 187-227, 241-251, 254, The Sudanese Muslim Factor in Uganda by Ibrahim El-Zein Soghayroun pg 49

All early surviving writings from Buganda by local scholars are printed books since field surveys for collecting old manuscripts have yet to be conducted. Besides written autobiographies from the late 19th century published by the missionary societies, Ham Mukasa and Apolo Kagwa brought back a printing press after their visit to England in 1902, which they immediately put to good use, and more private presses were acquired by Christian Ganda elites in the succeeding decades. Although publications by Muslim elites appeared relatively late in the 1930s and used the Latin script, some were based on older hand-written manuscripts written with the Arabic and Ajami scripts such as the 1920 travel account of Hajj Sekimwanyi. see: The Uganda Journal, Volumes 33-35: Luganda Historical writing by John Lowe 1893-1969, pg 19-25.

Colonial Buganda and the End of Empire: Political Thought and Historical Imagination in Africa by Jonathon L. Earle pg 155

Luganda Historical writing by John Lowe 1893-1969, Uganda Journal Vol. 33, pg 25-26)

*A. B. K. Kasozi writes that the Muslims at Bombo identify his home country as “Burunon”. This may be a Luganda translation of Bornu/Borno. The Spread of Islam in Uganda by A. B. K. Kasozi pg 252-254, The Sudanese Muslim Factor in Uganda by Ibrahim El-Zein Soghayroun pg 47

The Arab and Islamic Impact on Buganda during the Reign of Kabaka Mutesa by Oded Arye pg 217)

Country by Country Outline Survey of Muslim Minorities of the World, by Islamic Congress, Published 1977, pg 46.

The Comorian Presence in Precolonial and Early Colonial Congo by Xavier Luffin pg 6-9

Arabic and Swahili Documents from the Pre-Colonial Congo and the EIC (Congo Free State, 1885–1908): Who were the Scribes? by Xavier Luffin pg 281-283, History, archaeology and memory of the Swahili-Arab in the Maniema, Democratic Republic of Congo by Noemie Arazi et. al.

Arabic and Swahili Documents from the Pre-Colonial Congo and the EIC (Congo Free State, 1885–1908): Who were the Scribes? by Xavier Luffin pg 287-293,

On the Swahili documents in Arabic script from the Congo by Xavier Luffin, pg 21-22.

The History of Islam in Africa edited by Nehemia Levtzion, Randall L. Pouwels pg 295-296.

The History of Islam in Africa edited by Nehemia Levtzion, Randall L. Pouwels pg 264)

The Customs of the Swahili People by Mtoro bin Mwinyi Bakari (Trans. By J. W. T. Allen) pg 27-34.

À Stanleyville by A. Detry Published by La Meuse 1912, pg 7.

The Spread of Islam in Uganda by A. B. K. Kasozi pg 256-257)

À Stanleyville by A. Detry Published by La Meuse 1912, pg 8

À Stanleyville by A. Detry Published by La Meuse 1912, pg 9

For studies of the Riyadah Mosque manuscripts of Lamu, see Localising Islamic knowledge by Anne K. Bang, in ‘From Dust to Digital: Ten Years of the Endangered Archives Programme’ edited by Maja Kominko

Renewers of the Age: Holy Men and Social Discourse in Colonial Benaadir By Scott Reese pg 71-72, 145, 158-161, Stringing Coral Beads': The Religious Poetry of Brava (c. 1890-1975): A Source Publication of Chimiini Texts and English Translations pg 87.

Renewers of the Age: Holy Men and Social Discourse in Colonial Benaadir By Scott Reese pg 112-113, Muslim Brotherhoods in Nineteenth-Century Africa By B. G. Martin pg 160-161

Muslim Brotherhoods in Nineteenth-Century Africa By B. G. Martin pg 164-165

Muslim Politics and Resistance to Colonial Rule: Shaykh Uways B. Muhammad Al-Barawi and the Qadiriya Brotherhood in East Africa by B. G. Martin pg 473

Renewers of the Age: Holy Men and Social Discourse in Colonial Benaadir By Scott Reese p 121, 223-228, Muslim Brotherhoods in Nineteenth-Century Africa By B. G. Martin pg 163)

Islamic Sufi Networks in the Western Indian Ocean (c.1880-1940) By Anne K. Bang pg 34-35, 50-66)

Muslim Politics and Resistance to Colonial Rule: Shaykh Uways B. Muhammad Al-Barawi and the Qadiriya Brotherhood in East Africa by B. G. Martin pg 475-476, The Spread of Islam in Uganda by A. B. K. Kasozi pg 43

Muslim Politics and Resistance to Colonial Rule: Shaykh Uways B. Muhammad Al-Barawi and the Qadiriya Brotherhood in East Africa by B. G. Martin pg 477-485)

Muslim Politics and Resistance to Colonial Rule: Shaykh Uways B. Muhammad Al-Barawi and the Qadiriya Brotherhood in East Africa by B. G. Martin pg 472, Stringing Coral Beads': The Religious Poetry of Brava (c. 1890-1975): A Source Publication of Chimiini Texts and English Translations pg 88)

The Comorian Presence in Precolonial and Early Colonial Congo by Xavier Luffin pg 11-12, Muslim Politics and Resistance to Colonial Rule: Shaykh Uways B. Muhammad Al-Barawi and the Qadiriya Brotherhood in East Africa by B. G. Martin pg 485)

I'm accustomed to thinking of Swahili as referring to the language, how did it apply to a community?

What was the content of a lot of this learning? Was it really specific to shariah and general theological discourse, or did it bleed into what we could call philosophy?