The invention of Agriculture in Africa: plant domestication and the spread of African crops to Asia and the Americas.

The shift from hunting and gathering to agriculture and herding was among the most profound economic changes that occurred in human history.

During the African Neolithic, at least five independent regions of domestication emerged across the continent, resulting in the cultivation of around sixty different crops that were native to the continent, creating a wealth of indigenous forms of food production.

Africa contributed many crops to the global cornucopia, beginning with the transfer of African cereals to Asia during the 2nd millennium BC, and continuing into the Columbian exchange in the 16th century, when several African crops spread across the Americas, Europe, and S. East Asia.

The agricultural revolution in Africa gave rise to food surpluses, which led to the emergence of social hierarchies, increased trade, population movements, and early urbanism, which laid the foundations for the development of complex societies.

This article outlines the history of Plant domestication in Africa and the spread of African crops to the Old and New World.

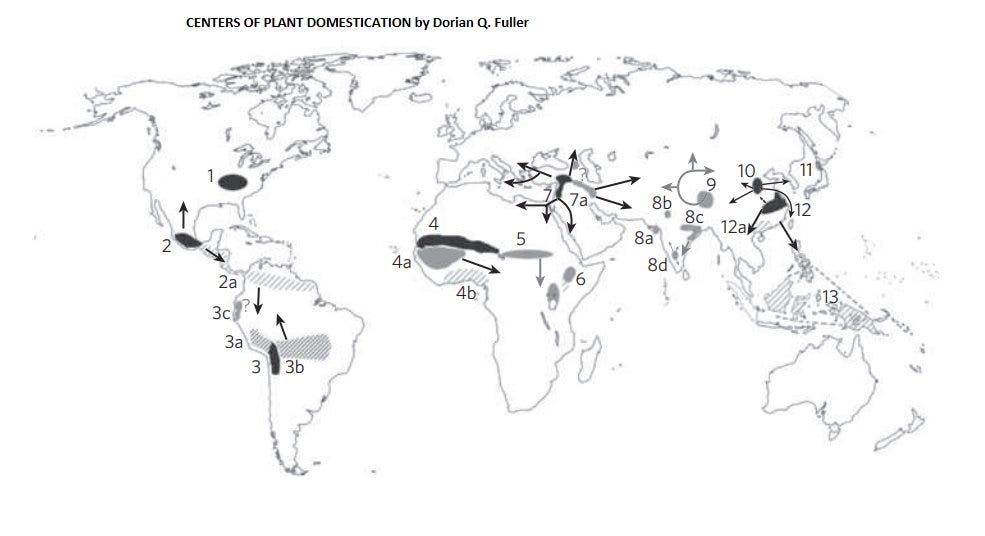

Map showing the Centres of plant domestication. Accepted primary domestication centres are shown in black, and potentially important secondary domestication centres are shown in grey.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Background on the history of the Agricultural Revolution

Humans were initially foragers and for a long time ate wild cereals, seeds, and nuts. But beginning around 11,000 years ago, foraging gave way to the cultivation of a few plant species. The transition from hunting and gathering to farming, which is known as the ‘Agricultural revolution’, was not a single event, but a complex, multi-stage phenomenon encompassing many discrete changes in human behaviour, plant morphology, and ecological structure.1

Domestication refers to the genetic and morphological changes that occur in a plant population in response to the selective pressures imposed by cultivation, while Agriculture is the form of land use that results from cultivation and/or domestication. Archaeological evidence suggests that hunter-gatherer groups independently began cultivating food plants in 24 regions around the world, at least 5 of which were in Africa.2

In Africa, different parts of the continent with their distinct environments, local resources, and cultures, witnessed different narratives in which people began managing certain plants closely and started processes of change that ultimately transformed subsistence economies, social structures, and landscapes.

While hard archaeological evidence for these processes is beginning to accumulate, reconstructing the antiquity of the full range of plant use in Africa using archaeobotanical remains challenging, as there is a strong bias toward food plants that survive in charred condition, such as cereals, rendering invisible those that easily decompose, such as tubers and leafy plants.3

Investigations of early crops and agriculture in Africa primarily rely on two data sources: modern botanical and ethnobotanical studies, and archaeological finds of ancient plant remains. Key aspects of archaeobotanical studies of plant domestication include: morphological assessment of a specimen’s wild vs domestic status; direct dating of ancient domesticates; and understanding the social, economic, and environmental contexts of early crop use.4

In Africa, many of the closest wild relatives of its domesticated plants have been identified as native to the continent. Knowledge of their modern geographic distributions, refined by genetic, systematic, and palaeoenvironmental studies, has resulted in the identification of at least five regions of initial cultivation.

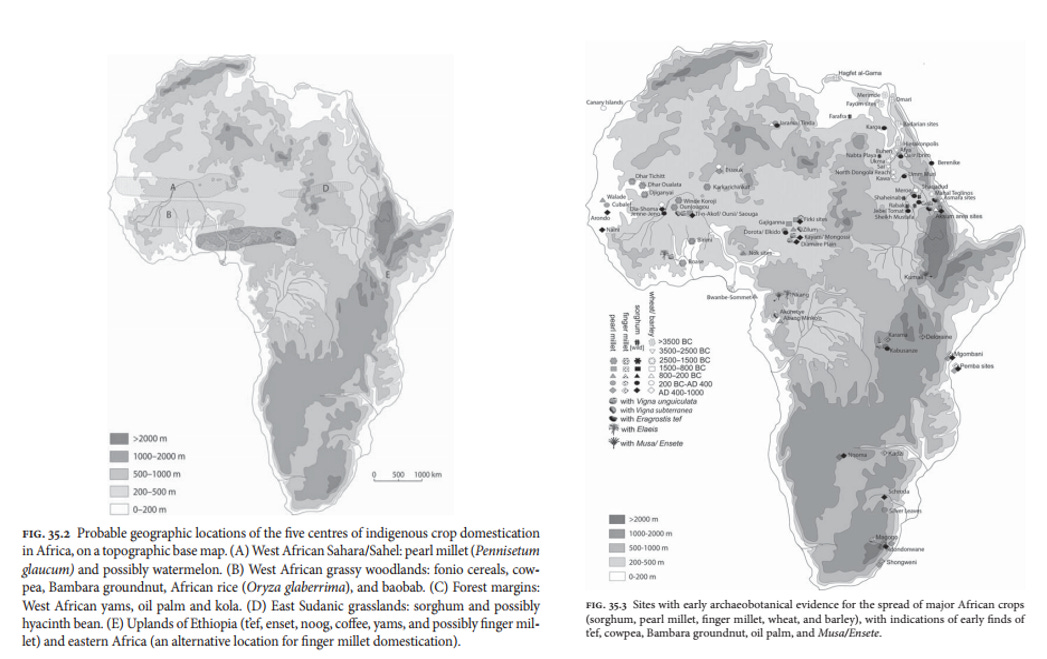

These centres of plant domestication in Africa include: the West African Sahel, the West African Savannah, the West African Forest, the East Sudanic Grasslands, and the Ethiopian highlands.

*Since the list of African plant domesticates contains as many as 60 crops, only a handful of the best-studied crops will be outlined in this essay.

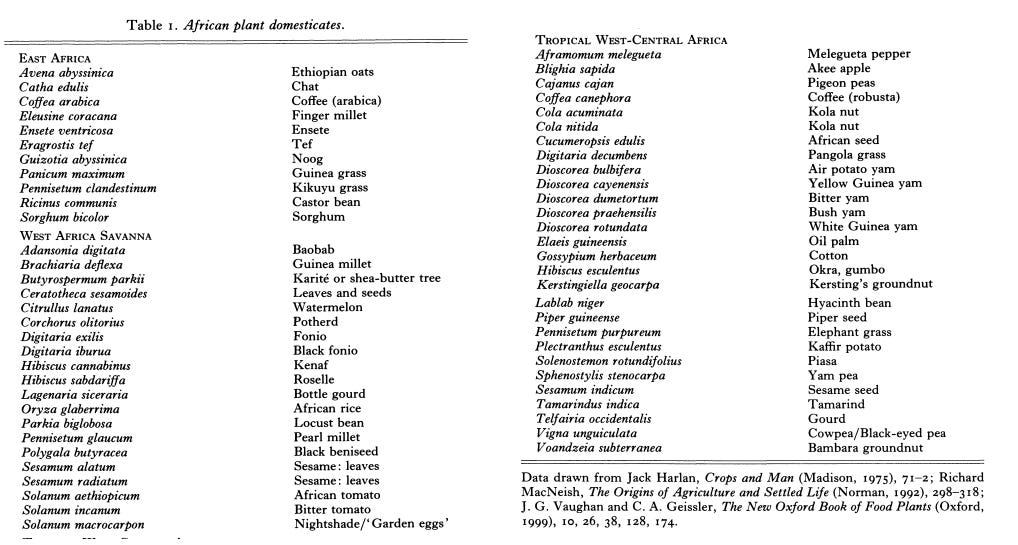

List of African plant domesticates by Judith A. Carney5

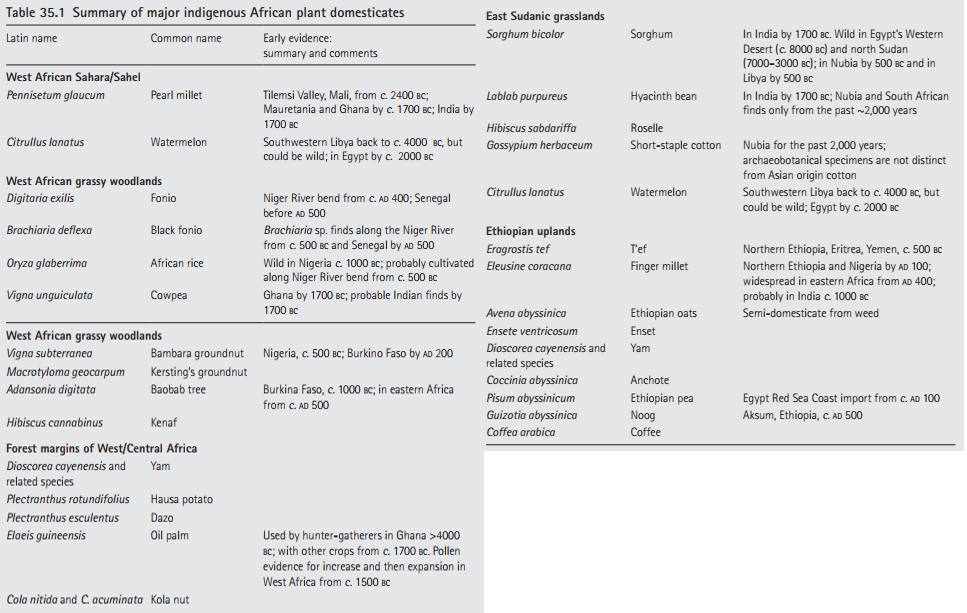

List of African plant domesticates by Dorian Fuller.6

The five centers of plant domestication in Africa and some of the sites with early archaeobotanical evidence for the spread of major African crops. Map by Dorian Fuller7

The West African centers of domestication

The main crop originating from the West African Sahel/Saharan regions was pearl millet, whose long process of domestication began during the 5th millennium BC, and was completed by 2400BC at the end of the Green Sahara period. Among African cereals, pearl millet has the most robust assemblages and datasets for tracking morphological changes during its domestication in Mali's Tilemsi Valley, before it was spread across many early Neolithic cultures in Africa and beyond the continent.

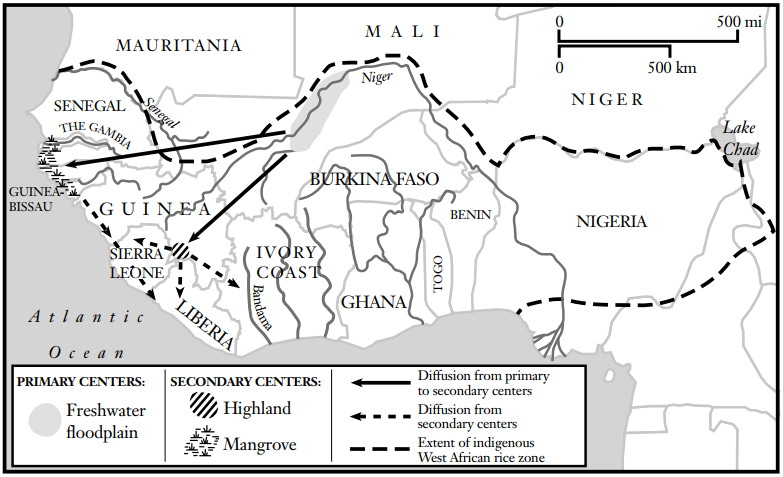

South of this region were the West African grassy woodlands, which were the origin of African rice (Oryza glaberrima), the fonio cereals, cowpea, the Bambara groundnut, and Guinea millet (Urochloa deflexa), among other crops.

The earliest archaeological remains of African rice have been obtained from the Inland Niger Delta region of Mali, where domesticated rice grains were found in the earliest occupation levels of Dia in the 8th century BC, and at Jenné-jeno in the 3rd century BC. The ancient grains show little change in size through time, indicating that rice was already domesticated by the time Dia was settled, suggesting that the process occurred much earlier.8

Centers of origin and diffusion of African rice. Map by Judith Carney

Ivory Coast, Aerial view of African rice paddies

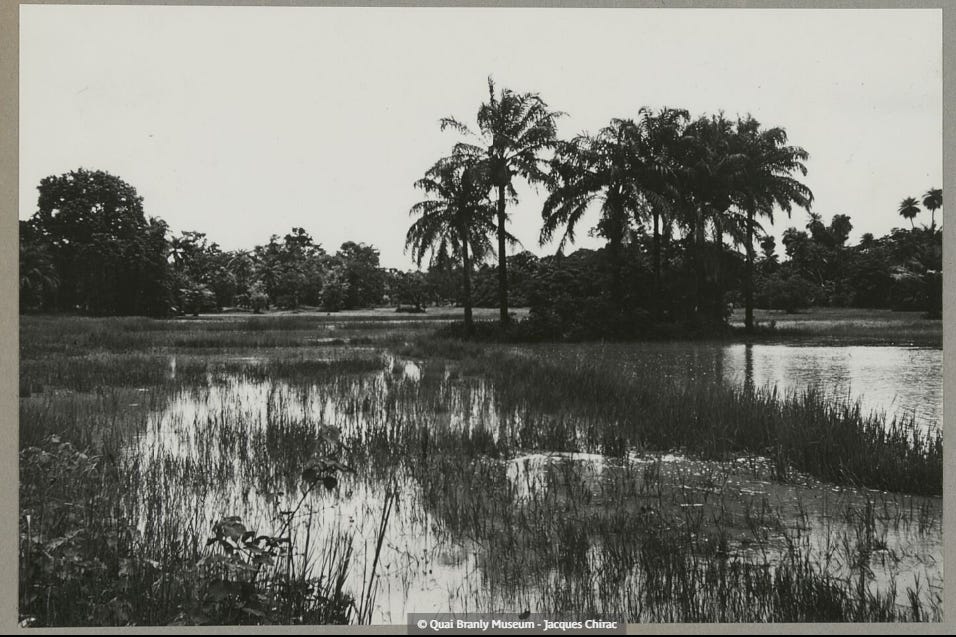

Flooded rice fields, Senegal, Quai Branly Museum

Rice Harvest in Guinea-Conakry, ca. 1901. Quai Branly Museum

The ‘White’ and ‘Black’ Fonio millets (Digitaria exilis Stapf, D. iburua Stapf) were domesticated independently of each other. White fonio, which is the more widespread of the species, was likely domesticated in the Inland Delta region of Mali. Its earliest known remains come from a late Tichitt site in the Mema region, dated to 850 BC. Black fonio is almost exclusively cultivated in the Nigerian highlands, where it was most likely domesticated.9

In the Forest region of West Africa, the beginnings of domestication are mostly known through historical linguistics since only a few of them left traces in the archaeological record.

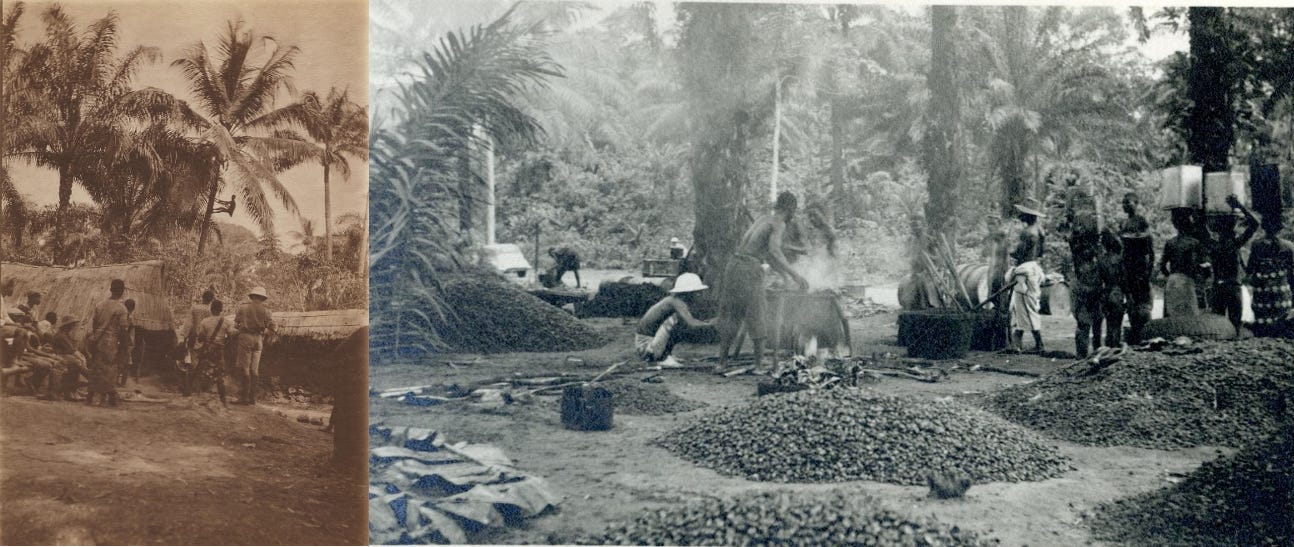

The main crops originally cultivated in this region include yams, oil palm, robusta coffee, Kola nut, African potatoes (Coleus rotundifolius and Coleus esculentus), and dozens of other crops. These trees and tubers have a deep antiquity among Niger-Congo speaking groups, at least as far back as Proto-Benue-Congo, which is several proto-language grades before the emergence of proto-Bantu, and are thus inferred to go back to around 2000-3000 BC.10

Excavations from the Neolithic site of Bosumpra in Ghana recovered Botanical samples of various domesticates, including endocarps of oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) from the 6th millennium BC, incense tree (Canarium schweinfurthii) from the 4th millennium BC, as well as Pearl millet and cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) from the 3rd millennium BC. Pearl millet and Cowpea also appear at the Kitampo sites in Ghana in the early 2nd millennium BC.11

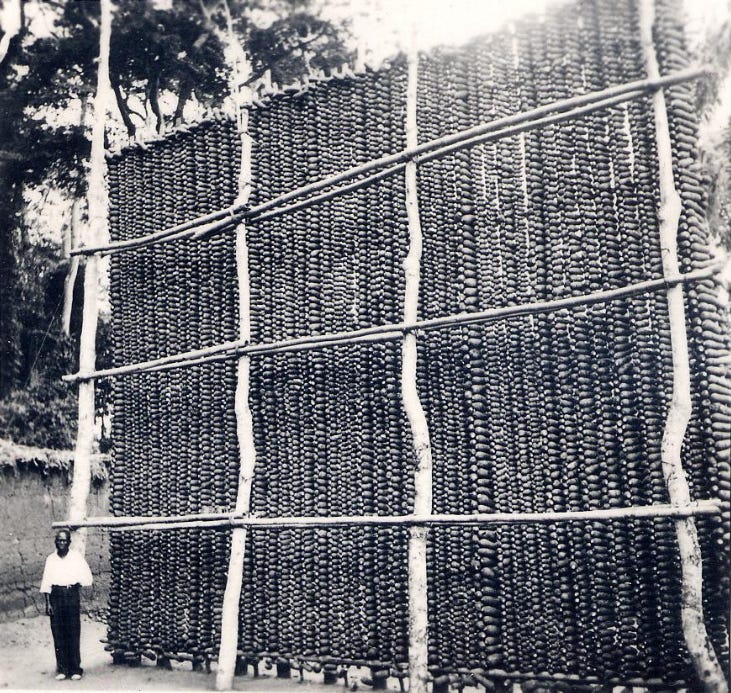

Stacks of yam tied in an Igbo yam barn, Nigeria. ca. 1880-1939. British Museum

(left) Harvesting oil palm in Nigeria. ca. 1916 (right) Scene of palm oil production in Côte d'Ivoire, ca. 1936. British Museum

The Sudanic and Ethiopian domesticates

The region extending from the Nubian Nile Valley to the Ethiopian highlands was the origin of several domesticates, including cereals such as Sorghum and t’ef, as well as cotton, watermelon, the oilseed noog, a local pea (Pisum abyssinicum), and the Ethiopian banana (Ensete ventricosum), among others. Early cultivation of eastern African yams, the anchote tuber crop, and Coffea arabica took place at lower elevations.12

Sorghum has long been recognized as originating from wild populations in Africa, with remains being recovered in the early Holocene site of Nabta Playa (S. Egypt), dated to 7500 BC. Firm evidence for domesticated sorghum remains has been recovered from the Neolithic sites of the Butana culture in eastern Sudan, dated to ca. 3600-3100 BC.13

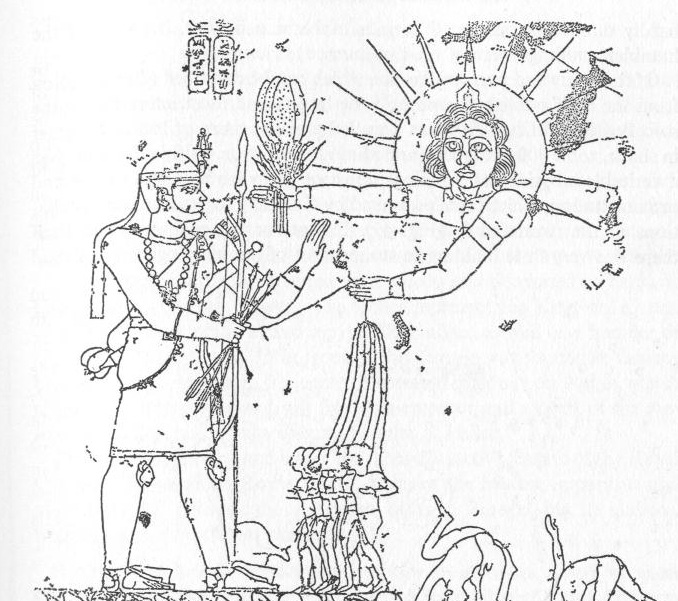

Meroitic rock drawing from Jebel Qeili, Sudan, depicting Prince Shorakaror receiving a bundle of Sorghum and defeated foes from a solar deity. The sorghum and defeated enemies represent prosperity/fertility and victory. The prince was part of the ruling trio with King Natakamani and Queen Amanitore, who ruled the kingdom of Kush 1st century CE. The rock drawing was found 92 miles east of Khartoum on the road to Kassala, not far from the Butana neolithic sites, where Sorghum was first domesticated.14

Painted Meroitic pottery depicting Sorghum plants.15

Wild cotton is native to Sudan, and was initially thought to be native to the West African Sahel as well, since cotton cultivation from both regions is sufficiently documented during the Middle Ages. So far, the only archaeological remains of early domesticated cotton have come from Qasr Ibrim in Lower Nubia, dated ca. 25 BCE–100 CE, and the Meroitic sites of Muweis and Hamadab. A recent archaeogenomic study has shown that Qasr Ibrim cotton belongs to the Gossypium herbaceum variety, native to Africa, and was therefore the result of an indigenous domestication process in Sudan.16

(left) Tapestry band showing a frieze a meanders and rectangular boxes filled with ankh crosses, made of light, dark blue, and natural cotton threads. Karanog, lower Nubia, Meroitic period. Penn Museum. (right) Tapestry fragment showing a frieze of deities, made of a linen warp and a cotton weft. Qasr Ibrim, Lower Nubia, Meroitic period. British Museum. images reproduced by Elsa Yvanez

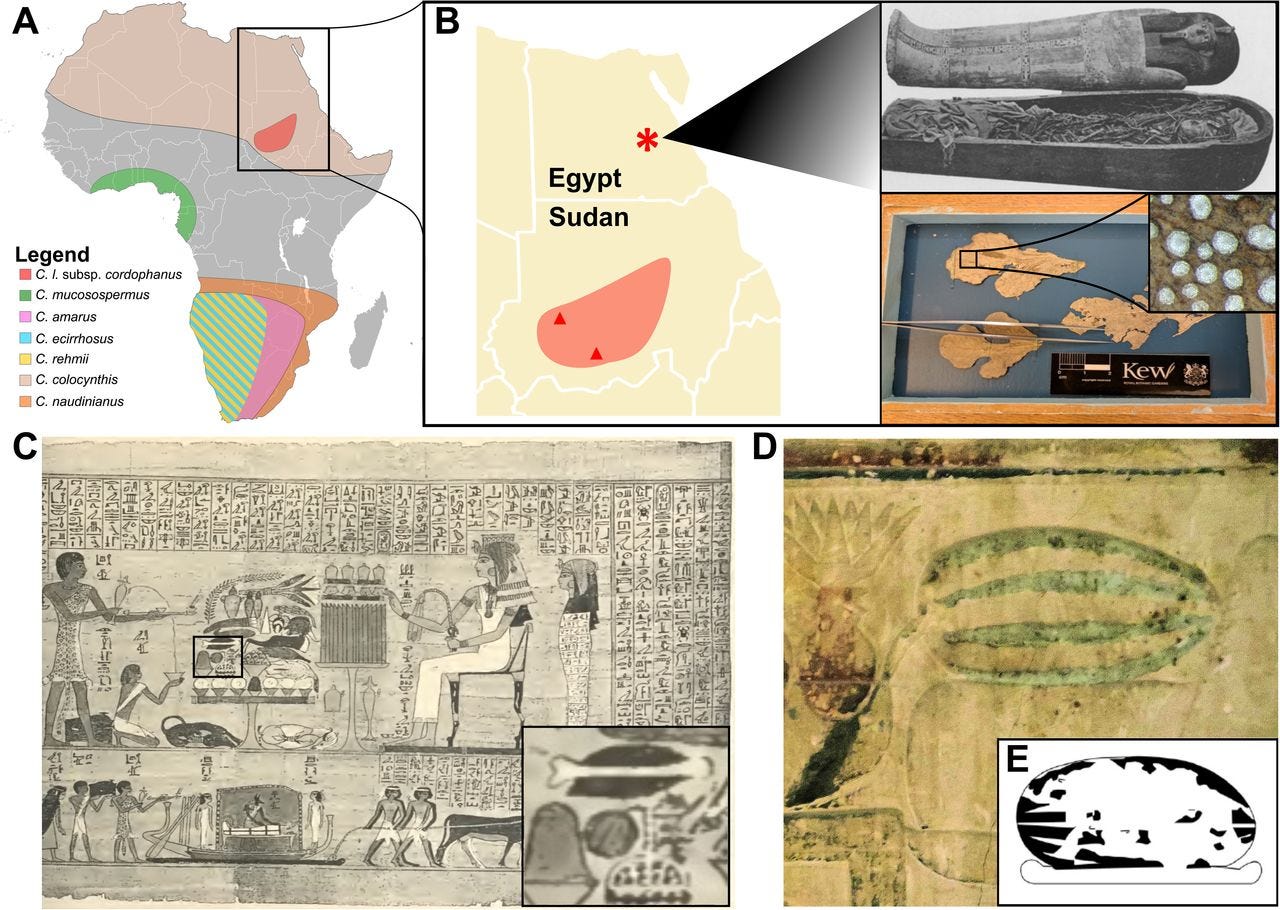

While earlier scholarship suggested that domesticated watermelons (Citrullus lanatus) originated in the West African Sahel, more recent hypotheses favour the Sudanese grasslands.

Genomic data from 6,000-year-old watermelon seeds from Libya and Sudan indicate affinities with the “egusi-type” watermelon of West Africa, which has edible seeds but a bitter white pulp. Genomic data from a 3500-year-old leaf from a Pharaonic sarcophagus shows that the red-fleshed watermelons of New Kingdom Egypt are instead more closely related to sweet, white-fleshed melons of Kordofan (Sudan) and Southern Sudan, where they were likely domesticated.17

Distribution of Citrullus species, archaeological samples and illustrations of watermelon in Ancient Egypt. Image by Susanne S. Renner et al

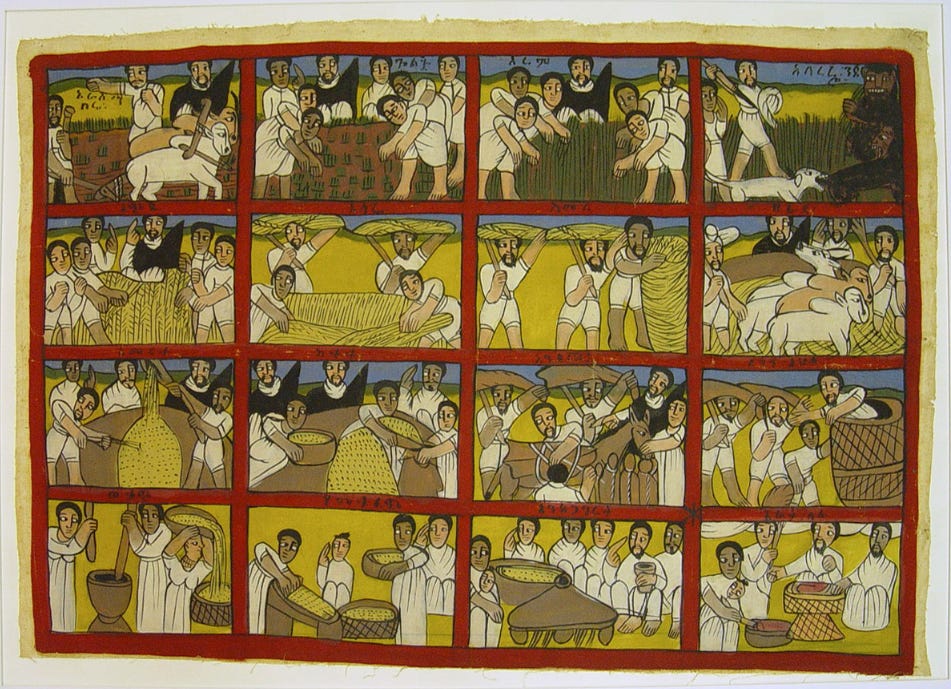

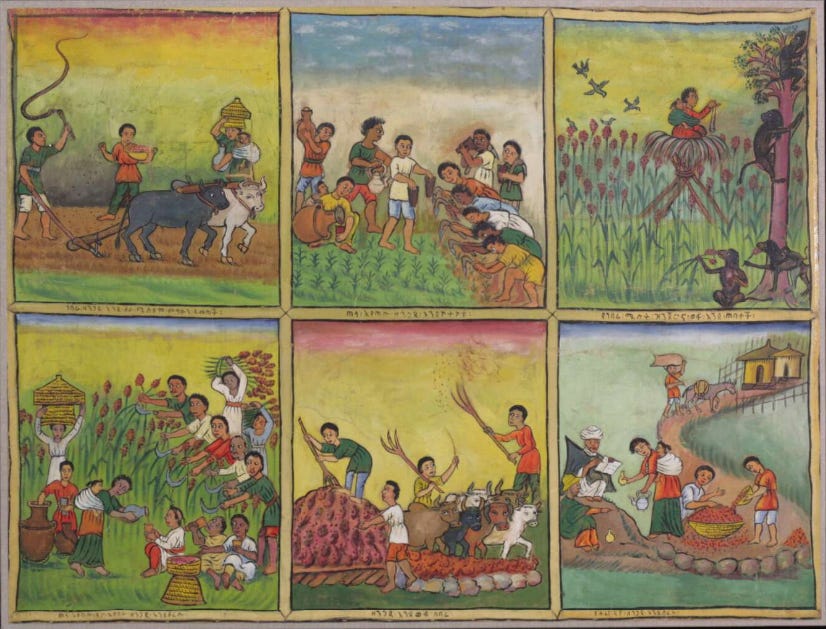

Archaeological evidence for Eragrostis tef, a cereal domesticated in the Ethiopian highlands and exclusively consumed in that region, is relatively sparse. The earliest known remains come from a number of locations dated to the late 1st millennium BC, including the Ancient Ona sites, as well as the pre-Aksumite sites of Beta Giyorgis and Kidane Mehret. Firmer evidence for both teff and noog cultivation comes from the Aksumite period in the early centuries of the common era, along with other African cereals like Sorghum and millet.18

Painting depicting farming in Ethiopia, early 20th century, British Museum.

Oil painting depicting agricultural scenes in Ethiopia, early 20th century. British Museum

The Spread of African domesticates within the continent and across the Indian Ocean world.

In Africa:

Crop species underwent range expansions after domestication, through a combination of human migrations and long-distance trade, which in many cases spread domesticated plants far from their centres of origin.

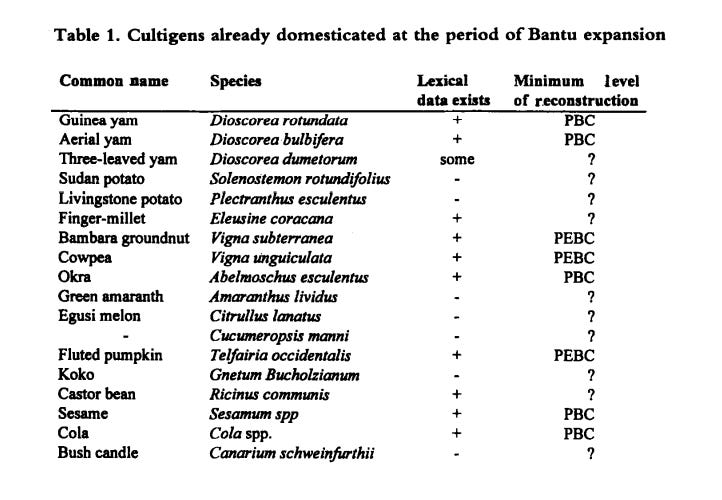

In the southern half of the continent, the spread of African domesticates and related farming techniques is often associated with the expansion of Bantu-speaking communities during the 2nd to 1st millennium BC. However, the paucity of early archaeobotanical evidence has continued to force archaeologists to privilege linguistics in developing more nuanced farming dispersal models for this region, especially for the three major African cereals, pearl millet, sorghum, and finger millet, and the legume cowpea and the Bambara groundnut.19

Map showing the main centers of crop origins and hypothesized routes of Bantu dispersal from Nigeria-Cameroon to eastern and southern Africa. Map by Alison Crowther et al

Outline of African plant domesticates available at the time of the Bantu expansion. Table by Roger Blench.20

Early evidence for pearl millet comes from several sites in southern Cameroon and the D.R.C., which are all dated to the late 1st millennium BC. The southern spread of pearl millet is rather intriguing, given that the humid forest was not an ideal place for its cultivation, suggesting different farming conditions in the 1st millennium BC than those in the modern era.21

Remains of Cowpeas dated to the 3rd century BC were recovered at the Neolithic Urewe site of Kakapel in Kenya, which also contains Sorghum and millet by the late 1st millennium CE. In South-Central Africa, the first record of cultivated cow peas is in Central Zambia, where seeds have been recorded from the 2nd century CE.22

By the mid-1st millennium CE, the three main African cereals (Pearl millet, Sorghum, and Finger millet) appear in numerous early Iron Age sites associated with Bantu-speaking communities extending from the East African coast to Southern Africa and West Central Africa.

Drystone terraces and settlement ruins of Bokoni, South Africa. Crops planted here included sorghum, pearl millet, finger millet, gourds, squash, melons, beans, and groundnuts.

Transport of sorghum and potatoes with terraced hills in the background. Rwanda, ca. 1965. Quai Branly Museum

Finger millet, which is thought to have been domesticated somewhere between Ethiopia and the East African Great Lakes, remains the only African cereal whose earliest archaeological evidence comes from outside the continent—in the Harappan sites of India.23

African crops in prehistoric Asia: the Harappan connection

Until the recent archaeological confirmation of the domestication of Pearl millet in Mali and Sorghum in Sudan, the limited archaeobotanical research on Africa meant that some of the continent’s most widespread domesticates were first discovered in India.

Agriculture in both Arabia and India today includes major contributions from African domesticates. In the dry-cropping regions of India, sorghum, pearl millet, and finger millet are traditionally the most productive grains, alongside cowpeas and hyacinth beans. All five of these species have their wild progenitors in different parts of sub-Saharan Africa. These finds testify to the importance of ancient long-distance contacts in the Indian Ocean world.24

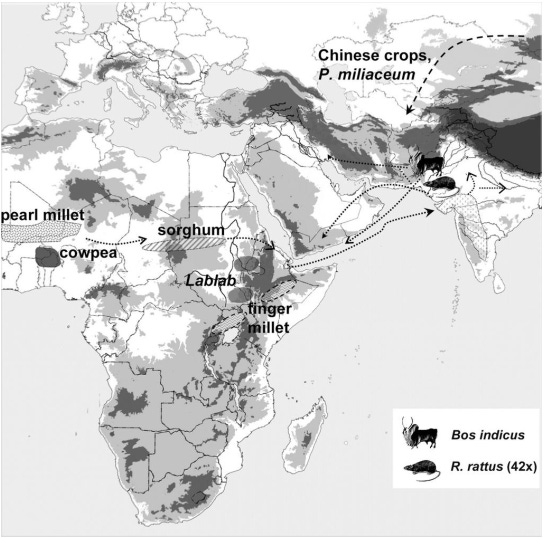

Transfers of domesticates between Africa and Asia during the prehistoric period. Map by Dorian Q. Fuller

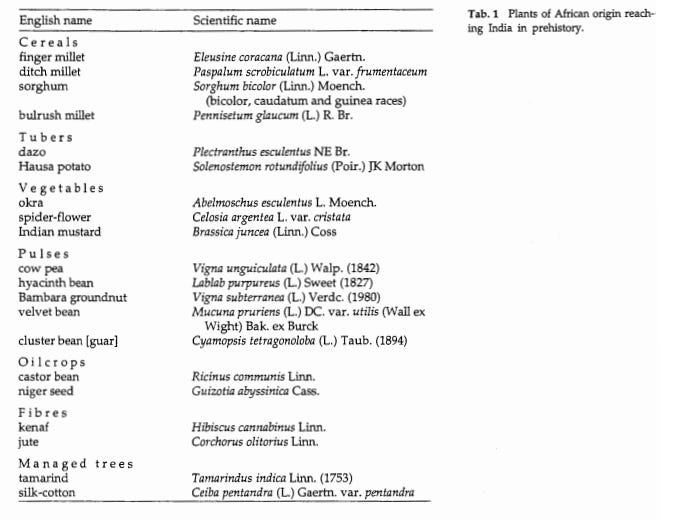

Plants of African origin reaching India in Prehistory. Table by Roger Blench.25

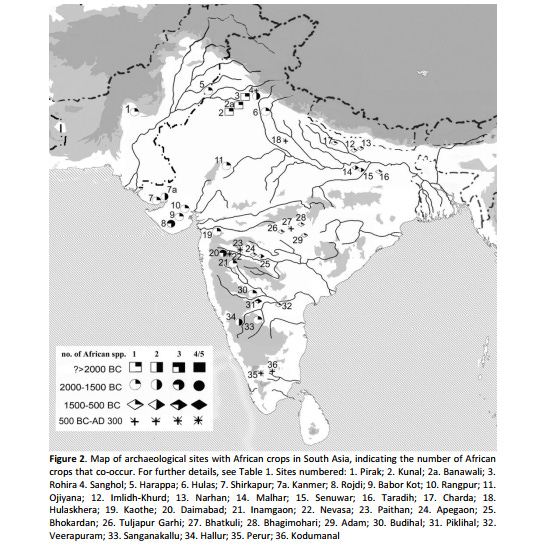

Southern India has firm evidence for pearl millet and hyacinth bean by 1600–1500 BC, sorghum by 1400 BC, and finger millet by 1000 BC. Some 33 archaeological sites in South Asia, dating from the Middle Bronze Age (ca. 2000 BCE) through the Iron Age (to ca. 300 BCE), have evidence for crops of African origin.26

In almost all instances, these crops co-occur with native Indian millets and pulses, and as such can be seen as additions to an existing system of summer monsoon agriculture. However, in several parts of the Indian subcontinent, the availability of African millets has marginalized indigenous small millets, much like the late introduction of Asian rice in West Africa would displace local rice crops during the 20th century.27

Archaeological sites in India with African crops. Map by Dorian Q. Fuller28

Several other African crops were also transferred to India during the prehistoric and historic periods, including cow pea, okra, ditch millet, castor, and the Hausa potato, among others, the last of which can be found as far as south-east Asia.29

It’s been suggested that the region between Eastern Sudan and the northern Horn of Africa was the main dispersion point of African cereals like pearl millet, finger millet, and Sorghum to the Arabian Peninsula and the Indian Subcontinent.30

The discovery of Broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum), of ultimately Chinese origin, at the Classic Kerma site of Ukma, Nubia, by ca. 1700 BC provides some support for this ancient Afro-Asian exchange route. Broomcorn millet arrived in Yemen by 2000 BC but is absent from contemporaneous sites in Mesopotamia and Egypt, indicating its arrival across the Arabian Peninsula.31

However, early evidence for the cultivation of African crops in Arabia during this period has yet to be discovered. Sorghum, pearl millet, and finger millet appear in Yemen and other parts of the Arabian peninsula during the common era (ie, in the historic period), around the same time that Asian domesticates like Oryza sativa (Asian rice) were introduced along the east African coast.32

According to the archaeologist Dorian Fuller, the prehistoric transfer of African crops to India took place at the end of the Harappan era and was likely indirect, given the lack of any other material evidence for Harappan contacts with the Red Sea region before 2000 BC.33

African crops in the Americas

The decades following Columbus’s arrival in the Caribbean launched an unparalleled exchange of crops between the Old and New Worlds in what has become known as the Columbian exchange. While studies of the Columbian exchange are often focused on the spread of Amerindian and Asian crops to Europe and Africa, relatively little attention has been directed to the African plant domesticates that were transported to the Americas and Asia during this period.

During the Trans antlantic slave trade, West African foods were key sources of sustenance for the enslaved Africans and later became important crops cultivated in the American plantations. These tropical crops were well-suited to agriculture in colonial America and Southeast Asia, and the African diaspora brought knowledge of the practices for their cultivation.34

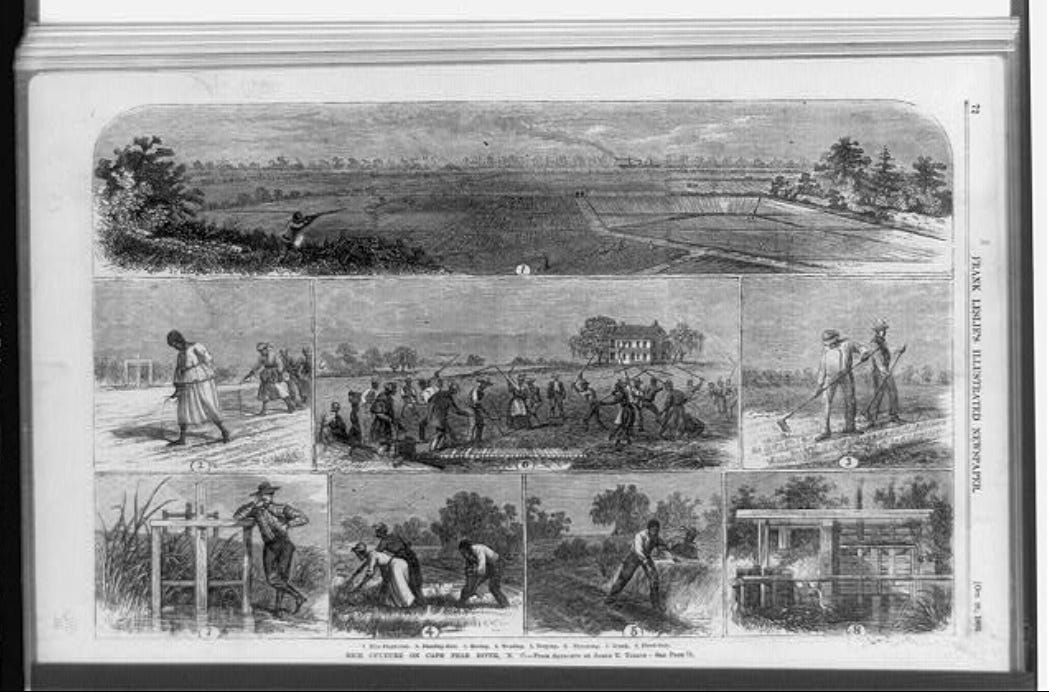

West African rice and rice-growing technology, which involved diking, transplanting, and other “intensive” practices, is first mentioned in medieval Muslim sources by al-Umari and Ibn Batutta, but is described in greater detail by the earliest Portuguese accounts, especially from the 15th and 16th centuries.35

Both African Rice and its rice-growing technology were introduced to the Americas (and Portugal*) by enslaved Africans, beginning in Brazil, Mexico, and the Caribbean during the 16th century, and later in South Carolina and other North American colonies by the 17th century.36

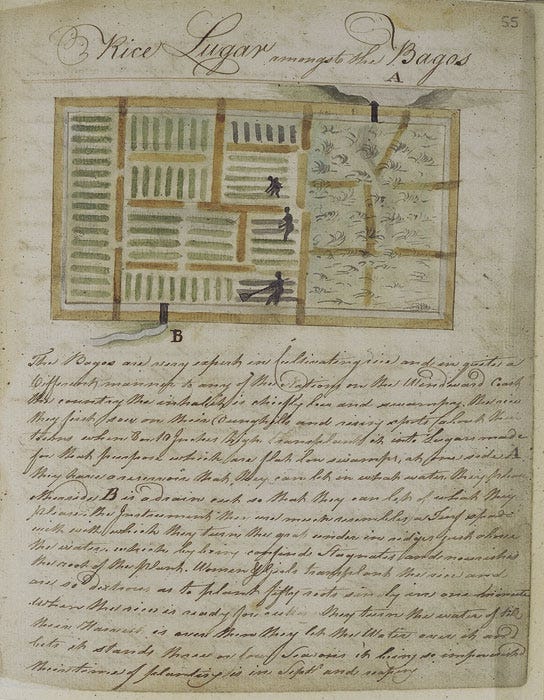

Depiction of Baga rice cultivation in Guinea Cornaky, ca. 1793 by Samuel Gamble. National Maritime Museum, London. image reproduced by Judith Carney

Rice culture on Cape Fear River, North Carolina, United States. ca. 1866 by James E. Taylor. Library of Congress. Eight illustrations showing a panorama of a plantation with a black man shooting at birds in the foreground, and other black farmers planting rice, hoeing, weeding, reaping, threshing, and a trunk and flood gate.

Other African crops transferred during the Columbian exchange include Cowpeas/Black-eyed peas, Castor Bean (Ricinus communis), Bambara Groundnut, and pigeon peas (Cajanus cajan), which are important plant protein sources in the Caribbean and southern United States. Additionally, grains such as Sorghum, starchy tubers like Yam, and other plants such as the Kola nut, Okra, Akee (Blighia sapida), and Oil Palm are present in parts of North and South America.37

Sorghum farm in Texas, U.S. image by AltaSeeds.

In the modern period, many of the African plant domesticates mentioned above remain staples of their original regions, especially pearl millet, yams, and teff, while other African crops have gained particular importance in commercial Agriculture outside the continent.

For example, the United States is the world's largest producer of Sorghum, followed not far behind by Ethiopia, while Brazil is the leading producer of coffee. Conversely, Côte d’Ivoire and Nigeria are the largest producers of Cocoa and Cassava, both of which are Amerindian crops.

Agriculture remains the single most important economic activity on the continent, employing about two-thirds of the population and serving as a primary driver of economic growth.

Coffee farm in Oromia, Ethiopia. image by FMC

During the mid-19th and early 20th centuries, two East African globe-trotters left behind a rich documentary record of their journeys between India, Oman, Yemen, France, Britain, and the United States. Their travel accounts and contrasting experiences are the subject of my latest Patreon article:

Please subscribe to read more about it here and support this newsletter:

The nature of selection during plant domestication by Michael D. Purugganan & Dorian Q. Fuller, pg 843

The Oxford Handbook of African Archaeology, edited by Peter Mitchell, Paul Lane, pg 509. The nature of selection during plant domestication by Michael D. Purugganan & Dorian Q. Fuller, pg 843)

Making the invisible visible: tracing the origins of plants in West African cuisine through archaeobotanical and organic residue analysis by Julie Dunne et al.

The Oxford Handbook of African Archaeology, edited by Peter Mitchell, Paul Lane, pg 510

African Rice in the Columbian Exchange by Judith A. Carney

The Oxford Handbook of African Archaeology, edited by Peter Mitchell, Paul Lane, pg 511-512

The Oxford Handbook of African Archaeology, edited by Peter Mitchell, Paul Lane, pg 513-514

The rise of African rice farming and the economic use of plants in the upper Middle Niger Delta (Mali) by S.S. Murray. Identifying African rice domestication in the middle Niger delta (Mali) by S.S. Murray In ‘Fields of Change: Progress in African Archaeobotany’ edited by René T. J. Cappers. The Rise and Fall of African Rice Cultivation Revealed by Analysis of 246 New Genomes by Philippe Cubry et al

Independent domestication and cultivation histories of two West African indigenous fonio millet crops by Thomas Kaczmarek et al. Mema in the History of West Africa: Economic Bases of Ancient Ghana and Mali by Shoichiro Takezawa and Mamadou Cisse. Vernacular names for African millets and other minor cereals and their significance for agricultural History by Roger Blench

Archaeology, Language, and the African Past by R. Blench, Wild trees in the subsistence economy of early Bantu speech communities: a historical-linguistic approach by K Bostoen

Bosumpra revisited: 12,500 years on the Kwahu Plateau, Ghana, as viewed from ‘On top of the hill’, by Derek J. Watson. Early domesticated cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) from Central Ghana by AC D'Andrea. Reconnecting the Forest, Savanna, and Sahel in West Africa: The Sociopolitical Implications of a Long‑Networked Past, by Stephen Dueppen. The Archaeology of Africa: Food, Metals and Towns edited by Bassey Andah, pg 250.

The Oxford Handbook of African Archaeology, edited by Peter Mitchell, Paul Lane, pg 513-514

Evidence for Sorghum Domestication in Fourth Millennium BC Eastern Sudan Spikelet Morphology from Ceramic Impressions of the Butana Group By Frank Winchell)

Introducing Meroitic Jebel Qeili: Shorakaror’s Victory Monument in context By Pavel Onderka, The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization By László Török g 466

Sorghum Paintings from the Meroitic Cemetery of Berber and Possible Implications for the Dispersal of the Plant across the Red Sea by Alemseged Beldados and Mahmoud S. Bashir, in ‘Stories of Globalisation: The Red Sea and the Persian Gulf from Late Prehistory to Early Modernity’ by Alemseged Beldados and Mahmoud S. Bashir

Cotton in ancient Sudan and Nubia: Archaeological sources and historical implications by Elsa Yvanez and Magdalena M. Wozniak. Cotton and post-Neolithic investment agriculture in tropical Asia and Africa, with two routes to West Africa by Dorian Q Fuller et al. Archaeogenomic evidence of punctuated genome evolution in Gossypium by Sarah A Palmer et al.

A chromosome-level genome of a Kordofan melon illuminates the origin of domesticated watermelons, by Susanne S Renner et al. A 3500-year-old leaf from a Pharaonic tomb reveals that New Kingdom Egyptians, by Susanne S Renner et al. Genome Sequencing of up to 6,000-Year-Old Citrullus Seeds Reveals Use of a Bitter-Fleshed Species Prior to Watermelon Domestication, by Oscar A. Pérez-Escobar et al

T'ef (Eragrostis tef) in Ancient Agricultural Systems of Highland Ethiopia by A. C. D'Andrea. The Agricultural Foundation of the Aksumite Empire, Ethiopia: An Interim Report by Sheila Boardman, in ‘The Exploitation of Plant Resources in Ancient Africa’ edited by Marijke Veen

Subsistence mosaics, forager-farmer interactions, and the transition to food production in eastern Africa by Alison Crowther et al. The Bantu Expansion: Some facts and fiction by Koen Bostoen

Linguistic evidence for cultivated plants in the Bantu borderland by Roger Blench

Pearl Millet and Other Plant Remains from the Early Iron Age Site of Boso-Njafo (Inner Congo Basin, Democratic Republic of the Congo) by Stefanie Kahlheber et al. Early plant cultivation in the Central African rain forest: first millennium BC pearl millet from Southern Cameroon by Stefanie Kahlheber et al. Plant and Land Use in Southern Cameroon 400 b.c.e.–400 c.e. by Stefanie Kahlheber et al. in ‘Archaeology of African Plant Use’ edited by Chris J Stevens

Early agriculture and crop transitions at Kakapel Rockshelter in the Lake Victoria region of eastern Africa by Steven T Goldstein et al, Linguistic evidence for cultivated plants in the Bantu borderland, by Roger Blench, pg 8

Exploring agriculture, interaction, and trade on the eastern African littoral: preliminary results from Kenya by Richard Helm. Missing Plant Foods? Where Is the Archaeobotanical Evidence for Sorghum and Finger Millet in East Africa? By Ruth Young and Gill Thompson in ‘The Exploitation of Plant Resources in Ancient Africa’ edited by Marijke Veen

Across the Indian Ocean: the prehistoric movement of plants and animals by Dorian Q Fuller

The movement of cultivated plants between Africa and India in prehistory by Roger Blench

Crops, cattle and commensals across the Indian Ocean: Current and Potential Archaeobiological Evidence by Dorian Q. Fuller and Nicole Boivin

Millets and Their Role in Early Agriculture by Steven A. Weber, pg 7

Crops, cattle and commensals across the Indian Ocean: Current and Potential Archaeobiological Evidence by Dorian Q. Fuller and Nicole Boivin pg 19

The movement of cultivated plants between Africa and India in prehistory by Roger Blench, pg 282

The Exploitation of Plant Resources in Ancient Africa edited by Marijke van der Vee, pg 105

On the Origins and Dissemination of Domesticated Sorghum and Pearl Millet across Africa and into India: a View from the Butana Group of the Far Eastern Sahel, by Frank Winchell, pg 498

Crops, cattle and commensals across the Indian Ocean: Current and Potential Archaeobiological Evidence by Dorian Q. Fuller et Nicole Boivin, pg 7-8

Across the Indian Ocean: the prehistoric movement of plants and animals, by Dorian Q Fuller pg 547

In the Shadow of Slavery: Africa’s Botanical Legacy in the Atlantic World by Judith Ann Carney

African rice (Oryza glaberrima): History and future potential By Olga F Linares, for medieval muslim sources see; Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 52, 70-71

With Grains in Her Hair’: Rice in Colonial Brazil by Judith A. Carney, Black Rice: The African Origins of Rice Cultivation in the Americas by Judith A. Carney. Deep Roots: Rice Farmers in West Africa and the African Diaspora, By Edda L. Fields-Black. for a more nuanced perspective, see Agency and Diaspora in Atlantic History: Reassessing the African Contribution to Rice Cultivation in the Americas by David Eltis et al. for the introduction of African rice in Portugal, see; *African knowledge transfer in Early Modern Portugal: Enslaved people and rice cultivation in Tagus and Sado rivers by Miguel Carmo et al.

African Rice in the Columbian Exchange by Judith A. Carney, pg 392-394

Wow such a detailed exploration of agricultural development. I am especially looking forward to digging into the references