On the history of the Bantu expansion: old misconceptions and new evidence

The southern half of the African continent is populated by speakers of about 550 closely related languages that are referred to as the Bantu languages.

The spread of the Bantu-languages across central, eastern, and southern Africa had a momentous impact on the continent’s linguistic, demographic, and cultural landscape. Bantu speech communities not only introduced new languages in the areas where they moved but also new lifestyles, including farming, metallurgy, and large states that shaped the cultural and political history of the region.

The estimated 550 Bantu languages spoken by over a third of the continent’s population today constitute Africa’s largest language family with an estimated 350 million speakers in 2019.1 Their distribution over a vast part of the continent is striking, and their origin, history, and interconnections have generated considerable discussion as well as several misconceptions.

This article explores the expansion of the Bantu-languages from a historical perspective, outlining the evolution of both the languages and their societies using the latest archeological and philological research from the pre-historic period to the start of the early modern era.

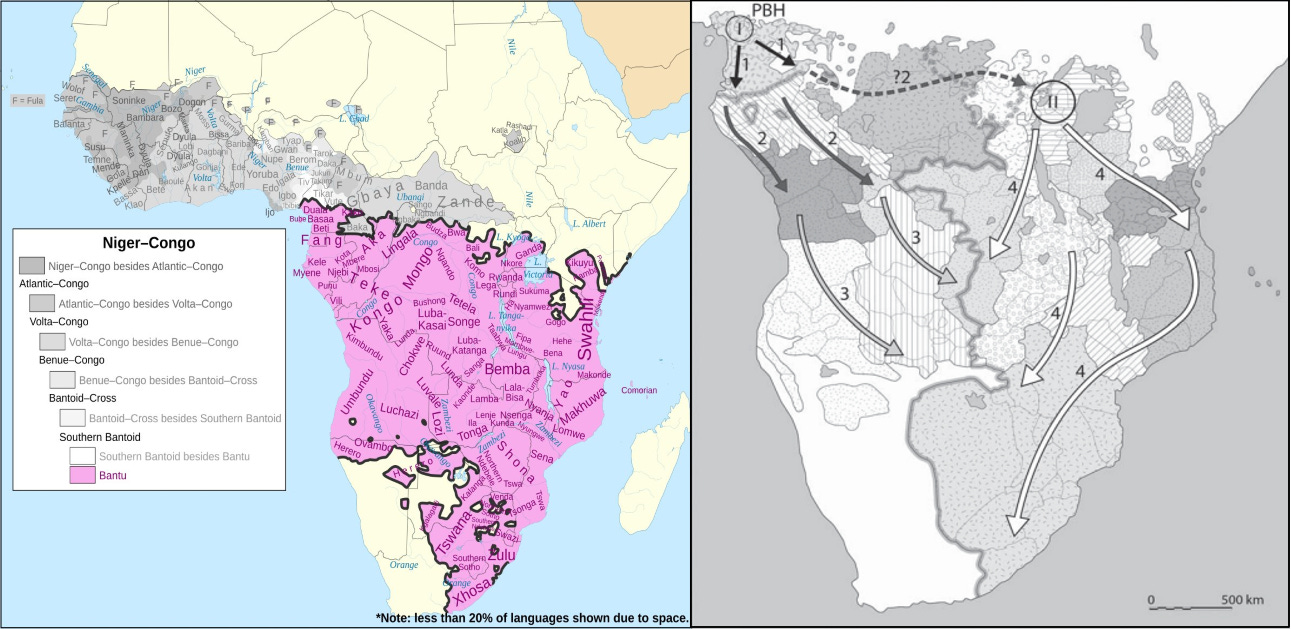

Map showing the distribution of the Bantu languages and their hypothetical dispersion routes.2

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more on African history and to keep this blog free for all:

A brief background.

The “Bantu Expansion” is the term commonly used to refer to the initial spread of the Bantu languages and communities over large parts of Central, Eastern, and Southern Africa. The Bantu language family crosscuts at least 23 countries, stretching from south-western Cameroon in the North-West, to southern Somalia’s Barawe (Brava) area in the North-East, and down to the continent’s southernmost tip.

“Bantu” is an artificial term based on the plural form for ‘people’ in most of the languages that fall under this umbrella. Its genealogical unity was established by the linguist Wilhelm Bleek in the 19th century and is today regarded by most linguists as belonging to the Niger-Congo language phylum, which is itself one of Africa's four major language phyla, including; Afro-Asiatic; Nilo-Saharan; and Khoe-San.3

Despite its vast geographic reach, the Bantu language family is only a sub-branch of a sub-branch of a sub-branch of the Benue-Congo branch of the Niger-Congo phylum. Within Benue-Congo, Bantu is part of the wider Bantoid family, which belongs to the East-Benue Congo branch. Bantoid itself splits up into South-Bantoid and a number of other branches. The Bantu language family itself then splits into four major subgroups; the “Central-Western,” “West-Coastal,” “South-Western,” and “Eastern” branches, of which the last branch was the largest.4

The phylogenetic position of Bantu within Niger-Congo corresponds to that of West-Germanic languages within the Indo-European phylum. The disproportionately large spread of Bantu-languages relative to their position in their phylum was therefore recognized by early scholars as having been enabled by other factors in the extra-linguistic world.5

Since this expansion of Bantu-languages occurred before the adoption of writing in the region and is beyond the limits of oral history, bodies of evidence from different sciences need to be studied, such as; archaeology; linguistics; evolutionary genetics; and paleoenvironmental evidence.

The earliest Bantu-speaking groups in Central Africa were not farmers.

Linguistic evidence indicates that the Niger-Congo Phylum emerged around 12,000-10,000 BP, and that Bantu languages diverged from it around 5-4,000 BP. The divergence of the Bantu branch from its closest relatives; the Bantoid subgroup of Niger-Congo’s Benue-Congo branch, provides the location of the language family's original “homeland” in the border region between S.E Nigeria and S.W Cameroon where it’s heterogeneous.6

Archeological and linguistic evidence suggests that a climate-induced destruction of the rainforest around 2,500 BP would have given a strong impetus to the Bantu expansion through West-Central Africa. Studies of the phylogeny of Bantu languages show that early Bantu-speaking populations did not randomly move through the equatorial rainforest but rather through emerging savannah corridors with dense rainforest environments imposing temporal barriers to expansion.7

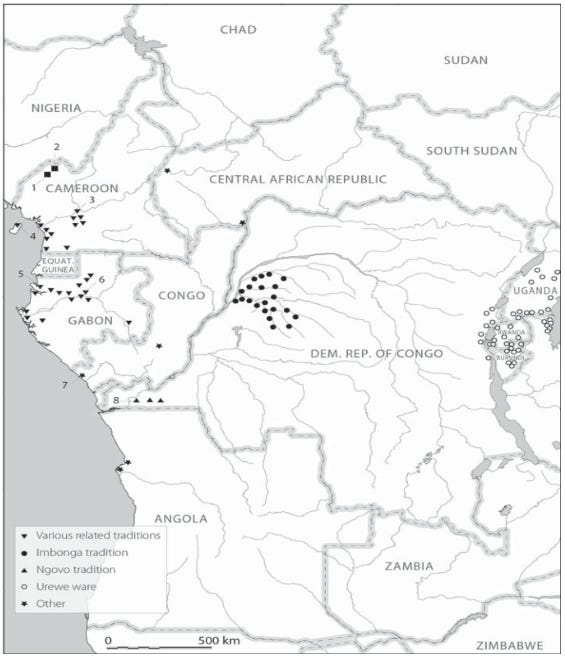

Map of Central Africa showing sites of the ‘Stone to Metal Age’ and their main traditions. (1) is Shum Laka. image by Pierre de Maret.

The gradual southward spread of initially Neolithic and subsequently Early Iron Age assemblages, clearly distinct from pre-existing Stone-Age industries, has since long been seen as the archaeological signature of Bantu speakers migrating through Central, Eastern, and Southern Africa. The archaeological site of Shum Laka, which is located within the Bantu ‘homeland’ and dates back to 7,000 BP, provides the earliest evidence for pottery making and advanced stone tools, followed later by sites in Central Cameroon and Gabon dated to 2600 BP.8

The material culture of these early sites included large blades and bifacial tools of basalt, as well as large polished stone tools, such as axes and adzes. These tools were likely used for intensified exploitation and protection of wild plants, such as trees ( oil palm) and tubers (yams), that were very prominent in the way of life of ancestral Bantu speakers, as the reconstruction of Proto-Bantu vocabulary has pointed out. While such tools suggest important changes in subsistence strategies, they cannot be taken as direct evidence for the farming of domesticated plants, which arrived after the initial Bantu expansion.9

Agriculture is often presumed to have been part of the so-called 'cultural package' that accompanied the dispersal of the Bantu-speakers, mirroring the spread of Austronesian or Indo-European languages. However, direct archeological evidence for early plant domestication in Central Africa is scarce during the initial period of Bantu expansion.

Pearl millet, which was first domesticated in the Sahel, appears in southern Cameroon (350 BC) and the Lulonga River in D.R.Congo (200 BC). According to the linguist Koen Bostoen, the only crops for which vocabulary can be reconstructed in ‘Proto-Bantu’ are; yams, the cowpea (Vigna unguiculata ), and the Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea), the latter of which was found at an archaeological site in southern Cameroon dated to 250CE.10

It’s therefore anachronistic and mostly inaccurate to refer to these early communities of Bantu speakers as ‘farmers’, or attribute their expansion to activities associated with agriculture as many scholars had previously surmised.

The Urewe Neolithic tradition and the putative role of Iron technology in the Bantu expansion.

In East Africa, the earliest archaeological assemblages commonly associated with the Bantu Expansion (of the 'Eastern Branch) are referred to as the Urewe Wares; an iron-Age Neolithic tradition that began around 600 BC and extended across a vast territory from Kivu in the Eastern D.R.Congo to the eastern shores of Lake Victoria in Kenya and down to Burundi in the South. Direct evidence for agriculture associated with the communities of the Urewe tradition is so far limited to the pollen of finger millet and sorghum at sites in Rwanda.11

Besides ironworking and cereal agriculture, the Early Iron Age complex of the Urewe tradition consisted of several other traits, such as settled villages (houses, grain bins, and storage pits) with large and small domestic stock. The ceramic traditions most closely related to Urewe wares are the Lelesu and Limbo ceramics from sites in Tanzania, dated 100BC-100CE, and the Kwale and Matola ceramics of the east African coast to southern Africa, dated to the 2nd century CE. These Early Iron Age traditions along the coast are the material signature of the earliest Eastern Bantu speech communities which drifted from the Great Lakes to South Africa in less than a millennium as corroborated by recent genetic research.12

The earliest archaeological evidence for iron working in Africa comes from the sites of Oboui (2300-1900BCE), Gbatoro (2368–2200 BCE), and Gbabiri (900–750 BCE), along the border region straddling eastern Cameroon and Central Africa, about 400km east of the Bantu homeland.13 Within the Bantu-speaking area, ironworking appears across multiple sites during the period between 800-400BC across a vast geographic area extending from Otoumbi and Moanda in Gabon, to Katuruka in Tanzania indicating early adoption of the technology.14

While ironworking is thought to have enabled the early Bantu expansion and has been characterized in some popular literature eg by Jared Diamond as the core of the “Bantu military-industrial” package which enabled them to clear forests and push foragers to the periphery15, most scholars, led by the eminent historian and linguist Jan Vansina, argue that there is little evidence for this “Bantu package” and even less evidence for the exaggerated role of ironworking during the early period of expansion.16

A recent study of archaeological sites in the Congo rainforest and adjacent areas by a group of scholars led by the archaeologist Dirk Seidensticker showed that early Bantu farming activity was at a scale so small that it was unlikely to have caused simultaneous changes in falling lake levels, drained swamps and thinning vegetation.

They instead suggest that the latter process of the drying forest is more likely what enabled the initial Bantu expansion, rather than the reverse. They also provide evidence for a wide-scale population collapse around 400-600CE that decimated the first iron-Age communities, before a latter wave(s) of Bantu expansion and new settlements emerged by the late 1st millennium CE. They also argue that the languages of the early communities likely went extinct and that present-day Bantu languages in the region may descend from those (re)introduced during the second wave of expansion.17

Ironworking was therefore not a significant factor in the initial movement of Bantu-speaking communities through the Congo basin, nor is it likely to have offered their small communities any overwhelming “military advantage”

On the Archaeogenetic history of the Bantu-expansion in relation to the Khoe-San populations.

New insights from the field of evolutionary genetics show that the Bantu Expansion was not just a spread of languages and technology through cultural contact, as was once thought, but involved the actual movement of people.

Studies in population genetics of Bantu-speaking communities have provided further evidence for their expansion, as indicated by their relatively low Y-chromosome diversity. Y-chromosomes are sex chromosomes inherited from fathers to sons, recent analysis of genetic data suggests the occurrence of successive expansion phases of Bantu speakers, indicating that the present distribution of Bantu languages does not necessarily reflect their original expansion. Genetic and Linguistic studies have also significantly contributed to the documentation of admixture between Bantu speakers and neighboring groups, such as the Nilo-Saharan, Afro-Asiatic, and Khoe-San speakers.18

The presence of mtDNA haplogroups associated with Khoe-San speakers in some Bantu-speaking groups provides evidence for Female-mediated admixture between both groups since mtDNA chromosomes are passed from mother to daughter. While these sex-biased admixtures were driven by sociocultural practices, such as patrilocality and polygyny, the presence of Y-chromosomal haplogroups from the Khoe-san in some Bantu-speaking communities such as the Kgalagadi and Herero indicates that the gene flow was not exclusively female.19

Khoe-San admixture in some Bantu-speaking populations of southern Africa and the functional load of clicks in the languages they speak. Table by Pakendork et.al.

Contact between Bantu speech communities and autochthonous forager groups is also reflected in the Bantu languages themselves; such as in the widespread Bantu root *-twa, which is often used to designate 'pygmies’ populations in Central Africa and Khoe-san communities in Southern Africa. Additionally, the presence of click-phonemes derived from Khoe-san languages provides evidence for a more intense contact with Bantu-speaking groups, especially among those whose maternal ancestry includes a significant percentage of Khoisan-specific mtDNA haplogroups, such as the Xhosa and the Zulu. However, some Bantu-speaking groups with a relatively high proportion of Khoe-San mtDNA such as the Kgalagadi and Tswana have no click sounds, which points to the importance of other social-cultural factors.20

The early relationship between the Bantu-speaking groups and the hunter-gatherers of Central, Eastern, and Southern Africa has been a topic of intense debate often influenced by modern political concerns.

An example of a popular narrative among non-specialists like Jared Diamond is the claim that the present distribution of the; “pygmy” foragers of the Congo Forest region, the Hadza and Sandawe foragers of Tanzania, and the Khoisan of south-western Africa, were all once part of a large geographic distribution of related groups speaking click-based languages that were “engulfed” by the Bantu-speaking farmers through conquest, expulsion, interbreeding, leaving only the linguistic legacy of their former presence.21

This view is however contradicted by most specialist research on the linguistic and genetic history of the Khoe-San groups and Central African foragers.

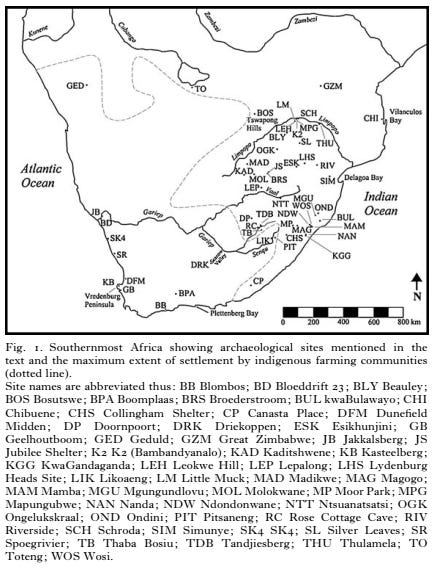

Archeological sites in southern Africa associated with Bantu-speaking and KhoeSan-speaking populations. Map by Peter Mitchell

A recent analysis of several studies on the genetic ancestry of modern Hadza and Sandawe foragers by the geneticists Viktor Černý and Luísa Pereira revealed that both groups showed a high genetic distance from the Khoe-San. “Both the Hadza and Sandawe showed a high genetic distance from the San, being as similar to the Khoi as they are to any other Bantu group or to each other. Thus, this evidence did not support a common ancestry for the Khoisan and East African foragers sharing the click sounds.” mtDNA studies of the Khoe-San groups pointed to the deep phylogeny and strong isolation of both San (mainly the !Kung) and Khoi (or Khwe) populations. The authors conclude that “Therefore, the divergence of all contemporary groups of analyzed foragers was completed long before the arrival of Bantu farmers”.22

A similar study done by several geneticists led by Krishna R. Veeramah, compared the KhoeSan-speaking groups, the Central African “pygmies” and speakers of Niger-Congo languages, showing that the lineage that gave rise to the Khoisan split off about 110,000 BP, much earlier than the lineages that eventually gave rise to the western “pygmies” around 32,000 BP and the Niger-Congo speakers around 10,000BP. The authors conclude that “there was a long period of independent evolution for the lineages leading to extant hunter gatherers and a longer period of shared history between Pygmy and Niger-Congo groups than between either of these groups and KhoeSan.”23

In all studies, the different groups of Foragers (“pygmy,” Hadza, Sandawe, and Khoisan) show greater genetic affinity with their immediate Bantu-speaking neighbors than with each other.

Linguists specializing in the Khoe-San languages argue that the presence of click sounds in their languages is by itself not a marker of a closely related group/continuum of languages like Diamond suggests, and is wholly unlike the linguistically and genetically related Bantu-speech communities. The Bantu languages are much younger and less heterogeneous than the Khoe-San languages, which consist of five independent units. According to the linguists Christa König and Rainer Vossen, the Khoesan language phylum has no ‘genetic unity’ and isn’t considered by most linguists to be a language phylum but is more of a convenience term.24

This is especially true for the Hadzane language of Tanzania which is often included in the ‘Khoe-San phylum’ but is in fact so dissimilar to other Khoe-San languages, that it’s considered a language isolate. The same is observed for the Sandawe language, which may have had some contact with the Proto-Khoe languages from which the languages spread over southern Africa emerged, but this contact falls short of establishing a genetic relationship between the two language units.25

The claim that the Khoe-San population of sub-equatorial Africa was fragmented by the Bantu expansion has been discredited by several scholars. As summarized by the archeologist John Kemp's monograph on the pre-Bantu history of southern Africa; the modern Khoe-San represent populations that were geographically distinct and highly differentiated, both among themselves and compared with other African populations, that have been isolated from other groups for tens of thousands of years, but which nevertheless share an ancestral cluster. This ‘ancestral cluster’ split up long before the Bantu expansion; estimated at 55-35,000 BP in the case of the splitting of the proto-Sandawe and the proto-Hadza from the rest of the proto-Khoe-San; and 20-15,000 BP for the split between the Sandawe and Hadza.26

On the emergence of early states across the Bantu-speaking cultural area.

In central Africa, the intensification of settlements during the 1st millennium BCE with evidence of cultivation, husbandry, metallurgy, pottery, and large refuse pits reflects the development of a more sedentary lifestyle contrasting with that of earlier foraging groups. However, this initial process of social complexification was likely halted by the population collapse of the mid-1st millennium CE mentioned above.

Its in southeast Africa and the east-African coast that the earliest forms of complex societies emerged in the Bantu-speaking area during the second half of the 1st millennium CE. The foundations of these societies were established at the turn of the common era, not long after the arrival of Eastern-Bantu speaking populations in the region.

Excavations at various sites near and along the coast of Tanzania by several archeologists such as Felix Chami have revealed evidence for the arrival of the Early Iron Age culture on the Tanzanian coast between the Rufiji delta and the Ruvu River at the close of the 1st millennium BCE, indicating the presence of Bantu-speaking farmers.

Sketch approximation of Ptolemy's map of east Africa, and the archeological sites of the Rufiji delta region, Mafia Island, and Zanzibar Island.

Excavations at the sites of Mkukutu-Kibiti and Kivinja (ca. 100BC-300CE) yielded local ‘Early Iron Working’ pottery (EIW) also known as Kwale wares (a branch of the Urewe tradition dated to 200BCE-500CE) as well as four Roman glass beads, they also revealed that a small river was diverted, likely for irrigation. The largest archaeological site from this period was found at Limbo, which is located in the hinterland just north of the Rufiji delta, and measured about 3000 sqm. Other excavation sites include the Machanga cave site on Zanzibar Island which contained local ceramics plus imported materials such as Roman and Parthian wares dated to the early 1st millennium CE.27

The Rufiji delta region is of particular interest to archaeologists since its identification as the probable location of the enigmatic emporium of Rhapta, an ancient city mentioned in Roman texts from the 1st century CE as one of three African metropolises known to them (the other two being Meroe in Sudan and Aksum in Ethiopia).

Excavations at the Ukunju limestone cave in Mafia Archipelago, just opposite the Rufiji delta revealed ‘Early Iron Working’ settlements with local pottery sherds of the Kwale/EIW tradition and the TIW tradition (100-500CE); glass beads from India and the eastern Mediterranean and inscribed Roman amphorae. The nearby site of Mwamba Ukuta contained the remains of a sea wall made of rectangular cement blocks enclosing an area of around 2.4km2.28

Map of Mafia Archipelago showing the location of the Ukunju Cave.

The ruined sea wall at Mwamba Ukuta, Mafia Island, Tanzania. images by Hannah Jane and Allan Sutton.

The gradual emergence of early complex societies along the East African coast can be seen in the settlement history of the Kuumbi cave near Zanzibar, where excavations have revealed a long stratigraphy with intermittent occupation periods since 20,000BP. Its last continuous occupation sequence begins in the first half of the 1st millennium CE, with material culture that includes some imported glassware, beads, and pottery from Rome and/or India, as well as local pottery of the TIW tradition. This local pottery tradition is considered to be the material signature of the North-east coast Bantu languages spoken near and along the East African coast from the 6th century. It has been found at early Swahili sites such as Unguja Ukuu (Zanzibar), Tumbe (Tanzania) and Shanga (Kenya).29

In South-eastern Africa, the earliest complex societies emerged near the confluence of the Shashi and Limpopo rivers in the late 1st millennium CE.

According to the archaeologist Thomas Huffman, the earliest material evidence for the presence of Bantu-speaking communities in this region is represented by the appearance of Kwale traditional wares at various archeological sites in the KwaZulu-Natal province (south Africa) dated to between 200 to 300 CE. This was followed by the Nkope branch in parts of eastern Botswana and the Kalundu Tradition in South Africa found at the site of 'Happy Rest' and Mapungubwe by 400CE. The Nkope branch ultimately evolved into the Toutswe facies, while the Kalundu communities collapsed in the drier climate and were succeeded by the Zhizho tradition at Schroda and the Leopard's Kopje tradition at K2/Bambandyanalo.30

Early polities, often referred to as chiefdoms, were centered at sites such as Toutswe and Bosutswe (700-1700CE) and Tholo (1184CE) in Botswana; as well as at Shroda (890-970 CE) and K2/Bambandyanalo (1000-1220CE) in South Africa, and Mapela Hill in Zimbabwe (11th century). The central sections of these Zhizo settlements encompassed cattle byres, grain storages, smithing areas, an assembly area, and a royal court/elite residence, in a unique spatial layout commonly referred to as the 'Central Cattle Pattern'.31

Its from this cultural tradition that the first kingdoms of the region emerged such as Mapungubwe (13th century) and Thulamela in South Africa, as well as Great Zimbabwe (13th-17th century) and Khami (14th-17th century) in southern Zimbabwe and eastern Botswana.

The Great Enclosure at Great Zimbabwe.

Relatively little archaeological research has been undertaken in the western and northern parts of the Bantu-speaking area concerning the period between the initial expansion and the emergence of early kingdoms around the end of the Middle Ages.

A few exceptions include the archaeological sites of the Upemba depression in southeastern D.R.Congo which provides a cultural sequence from the 5th century CE to the early 19th century and indicates the emergence of a hierarchical society by the end of the 1st millennium CE.

(left) Archaeological sites in the Upemba Depression, D.R. Congo. (right) Early Kisalian burial at Kamilamba, D.R. Congo. Note the ceremonial iron axe at the left center and the iron anvil to the left of the skull. images and captions by Graham Connah

According to the archaeologist Pierre de Maret, this cultural sequence commenced in the 5th century with the Kamilambian tradition, followed by the Kisalian tradition from the 8th to 14th century; followed by the Kabambian tradition whose last phases are comparable with the material culture of modern Luba communities. Thus, as de Maret claimed: “It becomes apparent that in establishing an Iron Age sequence in the Upemba rift one is actually studying the emergence of the Luba Kingdom.”32

A number of archaeological studies have also been conducted at several Iron Age sites in western Uganda which preceded the emergence of early states such as the Kitara kingdom. This region contains a series of archaeological sites associated with nucleated settlements and monumental earthworks between the Katonga River and Lake Albert.

Map showing the iron-age sites of the early 2nd millennium and the later kingdoms. Map by Peter Robertshaw.

The oldest of these is the site of Munsa, whose material culture includes local Urewe pottery, as well as metal jewelry and imported glass beads. The earthworks of Munsa, like those of other sites, consist of systems of ditches dug to a depth of about four meters and encircling a hill. Radiocarbon dates from the site indicate that it has a relatively complex history that spans a period from 900-1650CE, while construction of the earthworks lasted from 1450-1650CE.33

Other early archaeological sites include; Ntusi dated to the 11th century; Kibiro and Mubende which are dated to the 13th century; and the 15th-century site of Bigo, which is the largest of them and consists of a system of ditches and several earthen mounds. Construction of the earthworks required very substantial inputs of labour, which may have been organized by a state-level society. The archaeologist Peter Robertshaw argues each earthwork represented the center of a polity competing with its neighbors.34

Plan of earthworks at Bigo, Uganda. image by Graham Connah.

The nucleated settlement site of Ntusi has been described by some archaeologists as ‘an ancient capital site’. Excavations conducted by Andrew Reid identified archaeological material spread across 100 ha and dated its occupation to between the 11th and 15th centuries CE. The surrounding hinterlands of both Ntusi and Munsa contained over a hundred outlying sites of smaller sizes that were likely related. Robertshaw suggested that these sites represented early chiefdoms in a competitive political landscape and that their collapse by the 16th/17th century led to the rise of the Bunyoro Kingdom and other interlacustrine states such as Nkore and Buganda.35

In west-central Africa, the archeological site of Feti in Angola, which is described by Jan Vansina as “one of the largest known ancient sites anywhere in West Central Africa,” consists of several mounds, surrounding ditches, stone walls, and a royal tumulus’ dated to between the 9th and 13th century CE. The tumulus yielded iron hoes, knives, arrowheads, spearheads, anvils, and hammers. The site, which is part of a cluster of settlements with stone ruins covers an area of 7.5 ha. Vansina suggests that Feti, which lies in the heartland of Umbundu and Kimbundu speakers, was “the capital of a very large kingdom.”36

Excavations at other sites associated with the Umbundu and Kimbundu speakers have focused on similar stone burials such as the Kapanda necropolis in the Malanje Province. The necropolis consists of 23 circular tombs, the largest of which measures 4m at the base, is 1.8m tall, and has three internal chambers, windows, and a vaulted roof surmounted with stones.37

These funeral monuments are mentioned in multiple accounts, eg the capuchin priest Giovanni Cavazzi who visited the region during the 1660s. He described the tombs as typical of the “ancient” funerary tradition of the kingdom of Matamba (then ruled by the famous Queen Njinga) and were often reserved for royals/princes whose corpses were placed in a seating position, and their mouths were fitted with a pipe that allowed the prince to “communicate” with the outside world through the window.38

This latter account, and the archeological site of Feti, provide a clear historical link for the emergence of the Kimbundu and Ovimbundu kingdoms of central Angola

(top) “Graves of the Libôlos «magnates»”. ca. 1908, Angola. Arquivo Histórico Militar, Portugal. (bottom) “Aspects of the Pungo region - Graves”. ca. 1909, Angola. Arquivo Histórico Militar, Portugal.

The historic period in the Bantu-speaking area: Swahili manuscripts and other writings of Bantu languages.

The first written accounts that mention the societies established by Bantu-speaking groups were contained in the 1st-century Roman writings describing the east African coast (known to them as Azania), such as the Periplus and the geographical works of Strabo (d. 24 CE) Pliny (d. 79 CE) and Ptolemy (d. 170CE).

Strabo referred to them as the ‘Zangenae’ population and Pliny called them the “Zangenae”. Ptolemy mentioned a cape of the “Zinggis” while the 5th-century text of Cosmas Indicopleustes mentions a region “Zingyon”. This term would then reappear centuries later in the first Arab accounts of the East African coast by Al-Masudi (d. 945 CE), who describes it as the “land of the Zanj.” He also notes that the Zanj have “an elegant language,” a God called “mklnjlu” and are led by a king called Mfalme/Wafalme which meant “son of the Great Lord.” 39

(left) map of Swahili cities of the late Middle Ages (right) Swahili ‘dialects’ in the 19th century. Map by D. Nurse and T. Spear.

[*important to note that the so-called ‘standard Swahili’ is just the dialect spoken in Zanzibar known as KiUnguja.]

Most linguists, beginning with the work of Derek Nurse and Thomas Spear, identify these ‘Zanj’ populations of the late 1st millennium CE as primarily comprising modern Swahili speakers, whose language belongs to the Sabaki subgroup of the North-Eastern Bantu branch, alongside the Comorian, Mijikenda, and Pokomo languages.40

Sections of these coastal populations, especially the Swahili, adopted writing by the 8th century CE and composed manuscripts in their own languages. As late as the 19th century, several Swahili manuscripts continued to refer to rulers as Mfalme and many rulers in 18th century Kilwa included it in their names, pointing to the accuracy of al-masudi's account.41 The non-Muslim name for God rendered in unvocalized form by Al-Masudi as mklnjlu (subsequently altered by different copists) compares to ‘u-nkulu-nkulu’, a Bantu term for God, best attested among the more southern Bantu languages like Zulu, Ndebele, and Nguni.42

Swahili writers adopted the use of the Ajami script to write their language with Arabic characters, providing the earliest inscriptions of Bantu names/words.

Epitaph of Sayyida Aisha bint Mawlana Amir Ali b. Mawlana Sultan Sulayman, c. 1360, Kilwa, Epitaph of 'Mwana wa Bwana binti mwidani' , c. 1462, Kilindini, Mombasa.

These include the name ‘Mfahamu’ on an inscription found in the Kizimkazi mosque of Zanzibar dated 1107CE, which according to the historian Abdul Sheriff is probably “among the earliest evidence of a Swahili term for ruler, mfaume/mfalme” and “may be the first inscription of a Swahili word on stone.” Numerous epitaphs include Swahili honorific titles, names, and other Swahili terms of Bantu derivation such as “Sayyida 'A'isha bint Mawlana” on a 1360 or 1550 tomb in Kilwa, “Mwana wa Bwana” on a tomb dated to 1462 near Kilindini, and “Mwinyi Shummua b. Mwinyi Shomari” on a 1664 tomb in Kwale, and “Mwinyi Mtumaini” on a tomb dated 1670.43

In these examples, the word ‘Mwana’ meaning child in Swahili is also commonly found among other Bantu languages, while Mwinyi or Mwenye ' is a Bantu root that means ‘sovereign’ or ‘owner,’44 and was the title of the traditional Swahili rulers of Zanzibar during the 19th century. (both ‘Mwana’ and ‘Mwene’ also appear in 16th-17th century documents from the kingdom of Kongo much further west in Angola with the same usage and meaning,45 and the title of ‘Mwene Mutapa’ for the king of Mutapa much further south at Zimbabwe.)

The Mwinyi Mkuu’s palace at Dunga, ca. 1920. Zanzibar, Tanzania.

The Kikongo language and the comparative spread of African and European languages from the 16th to 20th centuries.

On the western side of the Bantu-speaking area, the first written descriptions of the region's kingdoms began with the arrival of the Portuguese on the coast of the kingdom of Kongo in 1483.

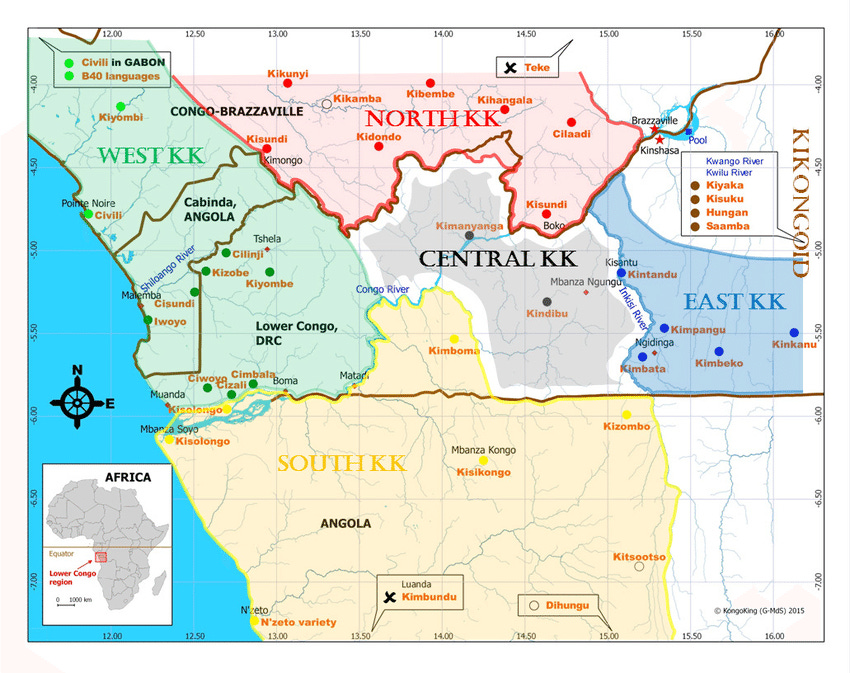

The elites of Kongo subsequently adopted writing and produced their own written accounts, the bulk of which were written in the Portuguese language. However, many of them contain words, names, ethnonyms, and toponyms in the ‘Kikongo language Cluster’ —a group of 50 closely related languages that belong to the West-Coastal branch of the Bantu language family.46

The Kikongo Language Cluster (KLC), with its sub-groups mapped By Gilles-Maurice de Schryver et al.

By the 17th century, a number of bilingual manuscripts in both Kikongo and Portuguese were composed such as the Portuguese– Kikongo catechism from 1624, a trilingual wordlist from 1652, and a grammar of Kikongo published in 1659. While these manuscripts are not old enough to yield significant insights into deep-time Bantu language history, they are of key importance for gaining a better historical understanding of the Kikongo Language Cluster.47

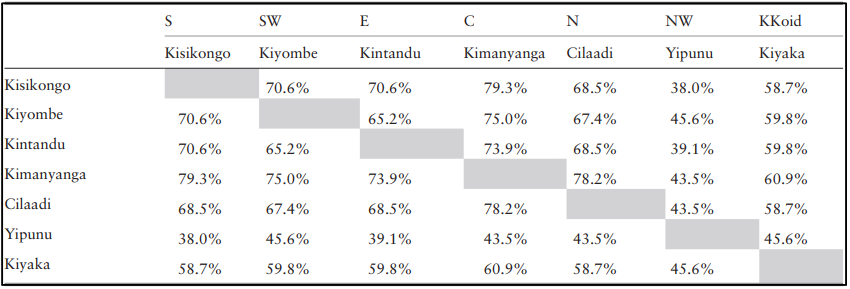

According to the linguists Koen Bostoen and Gilles-Maurice de Schryver, the Kongo documents show that the kingdom of Kongo wasn't a monolingual polity of Kikongo speakers as often presumed but was comprised of many different languages. They show how these different languages are now subsumed as ‘dialects’ under the modern classification of the ‘Kikongo language cluster,’ despite their lexical similarity being lower than that between Standard Dutch and Modern Standard German (76.8%) yet the latter two aren't considered dialects but ‘full languages’ (*see table below). They found that the 17th-century documents were all written in the language spoken at the capital; Mbanza Kongo and its immediate vicinity.48

Basic vocabulary similarity rates between modern ‘dialects’ of the Kikongo language. table by Koen Bostoen

The authors thus reiterate the argument of the historian Wyatt MacGaffey that the modern Kikongo language “is a relatively recent political construct that emerged within the very specific context of early-twentieth century European colonialism characterized by both rising discontent with foreign rule and awareness of incipient competition within the colonial framework between the Bakongo and other “tribes” identified as such by the administration.”49

In this regard, the spread of the Kikongo language from the capital to the outlying regions at the expense of regional dialects is similar to the spread of Parisian French in 19th-century France and the spread of Italian in 20th-century Italy.

According to the linguist Anthony Lodge, barely 11% of the French population could speak Parisian French (so-called 'standard French) in 1794 since most spoke local “dialects”. This figure rose to 69% by 1867, as “dialects were until quite recently persecuted with great ruthlessness” by the state.50 In the latter case, the Italian linguist Tullio De Mauro estimated that less than 30-20% of Italy's population spoke Italian on a daily basis as recently as 1950 before its popularization in the country by mass media which led to the decline/death of other “dialects”.51

(left) A modern map of the languages and dialects of France (right) Map by Anthony Lodge showing the proportion of ‘French-speaking’ peoples in France in 1863.

16th century Portuguese accounts of the Bantu-languages of South Africa.

In the southernmost part of the continent, Bantu-speech communities first appear in documentary accounts of the shipwrecked Portuguese sailors who reached the southern tip in 1488 and visited the region in the early 16th century.

Description of societies in south-eastern Africa by shipwrecked Portuguese sailors in 1552, 1558, 1593-1594 and 1622, leave little doubt that the state-level agro-pastoralist communities they encountered were the precursors of the same Bantu-speaking communities currently found in the region. While these Portuguese accounts are useful as historical sources since they predate the more detailed Dutch accounts by over a century,52 they don't contain much useful information for the study of the region's linguistic history.

Only a few words were reproduced by the Portuguese writers in their original Bantu form. They include; nouns (eg: assegais/azagayas, ie: spears); endonyms, and toponyms (eg: Makomates, Viragune, Mokalapapa, Vambe, the Maputo/Maputa River) titles and names (eg: Inhaca/Inyaka for King and Inkosis/Inkosi for chief).

In the case of the shipwreck of Santo Alberto along the Transkei-Natal coast (modern Eastern Cape province) in 1593, the Portuguese were able to communicate with the local ruler because one of their slaves “spoke his language” which the historian Elizabeth Eldredge suggested to be isiXhosa or isiZulu, thus indicating the presence of these languages long before the emergence of the Xhosa and Zulu kingdoms.53

Map showing the kingdoms and empires of the southern half of Africa in 1880. Map by Sam Bishop.

Conclusion: the complex history of the ‘Bantu expansion’.

As shown in the example of the analysis of the Kikongo cluster, modern Bantu languages are a product of centuries of evolution like all other languages. Genetic studies of modern Bantu-speaking populations indicate that their Y-chromosome variation did not shrink with distance from the putative homeland, thus indicating that the original founder event was erased by later waves of forward and backward migrations.54

This theory, which was initially proposed by linguists, has since been corroborated by the abovementioned archaeological research in the rainforest region, as well as by known historical events such as in the Lozi kingdom of Zambia, where the ‘Siluyana’ language disappeared in the 19th century after being displaced by the ‘Sikololo’ language of their southern conquerors.55

The linguist Koen Bostoen argues that such recurring migration/dispersion events would have led to internal language shift and language death, concluding that present-day Bantu languages may not reflect the distribution of their ancient precursors:

“As it still happens today, possibly on a larger scale than in the past due to mass media and schooling, individual Bantu speakers or larger communities gave up their first language in favor of another Bantu language, which may have guaranteed more economic or social success.”56

The History of the Bantu-languages and their expansion is therefore just as complex, multifaceted, and fluid as the history of the societies they established across the southern half of the continent. Hopefully, the recent interest in the study of manuscripts from pre-colonial Bantu-speaking societies across the region will help close the gaps in our knowledge of this vast language family and its contributions to Africa’s rich linguistic history.

Palace of the Lozi king at Lealui, ca. 1916, Zambia. USC Libraries.

During the pre-colonial times, some traditional African religions were spread by their adherents over a much wider geographic region than their present geographic reach suggests.

My latest Patreon article explores the spread of the west African traditional belief systems associated with the gods Dan and Dangbe, whose religious traditions were spread across west Africa and the Atlantic world to Brazil, Haiti and Louisiana.

please subscribe to read about them here:

The Bantu Languages by Mark Van de Velde pg 3

first map from Wikimedia commons, second map reproduced by Pierre de Maret

The Oxford Handbook of African Archaeology edited by Peter Mitchell, Paul Lane pg 628-629,

Moving Histories: Bantu Language Expansions, Eclectic Economies, and Mobilities by Rebecca Grollemund et al, pg 2-4.The Bantu Expansion: Some Facts and Fiction by Koen Bostoen pg 227

The Bantu Expansion by Koen Bostoen (2018) pg 4-5, The Bantu Expansion: Some Facts and Fiction by Koen Bostoen pg 228)

The Bantu Languages by Mark Van de Velde pg 4-5

Bantu expansion shows that habitat alters the route and pace of human dispersals by Rebecca Grollemund et al.

The Bantu Expansion by Koen Bostoen (2018) pg 6, The Oxford Handbook of African Archaeology edited by Peter Mitchell, Paul Lane pg 631-635

The Bantu Expansion by Koen Bostoen (2018) pg 6-7

The Bantu Expansion by Koen Bostoen (2018) pg 4-5, The Bantu Expansion: Some Facts and Fiction by Koen Bostoen pg 230-232)

The Oxford Handbook of African Archaeology edited by Peter Mitchell, Paul Lane pg 635-636,

Iron Technology in East Africa: Symbolism, Science, and Archaeology by Peter Ridgway Schmidt pg 16-18, Along the Indian Ocean Coast: Genomic Variation in Mozambique Provides New Insights into the Bantu Expansion by Armando Semo

The Origins of African Metallurgies by A.F.C. Holl pg 7-8, 12-13, 21-31

From a Plain Appointment to a Full Blown Relationship" by Bernard Clist, A Critical Reappraisal of the Chronological Framework of the early Urewe Iron Age Industry by Bernard Clist.

Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies by Jared M. Diamond pg 394-397

New Linguistic Evidence and 'Bantu Expansion' by Jan Vansina

Population collapse in Congo rainforest from 400 CE urges reassessment of the Bantu Expansion by Dirk Seidensticker et al.

The Bantu Expansion by Koen Bostoen (2018) pg 10)

Prehistoric Bantu-Khoisan language contact A cross-disciplinary approach by Brigitte Pakendorf et. al pg 15, Genetic substructure and complex demographic history of South African Bantu speakers by Dhriti Sengupta et al.

Prehistoric Bantu-Khoisan language contact A cross-disciplinary approach by Brigitte Pakendorf et. al, pg 14-17 The Bantu Expansion Some facts and fiction Koen Bostoen pg 283)

Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies by Jared M. Diamond pg pg 383-384, 385-86)

Archaeogenetics of Africa and of the African Hunter Gatherers by Viktor Černý and Luísa Pereira pg 9-10)

An Early Divergence of KhoeSan Ancestors from Those of Other Modern Humans Is Supported by an ABC-Based Analysis of Autosomal Resequencing Data by Krishna R. Veeramah et a.l 626

Khoisan Languages by Christa König, The Khoesan Languages edited by Rainer Vossen pg 14-23, Genetics and Southern African prehistory: an archaeological view by Peter Mitchell pg 74-75)

The Khoesan Languages edited by Rainer Vossen pg 20-22, 33-36, The Hadza: Hunter-gatherers of Tanzania By Frank Marlowe pg 15-17

Malawi and eastern Zambia before the Bantu W.H.J. Rangeley’s “Earliest Inhabitants” revisited 50 years on by John Kemp Part 2 pg 2-3)

Ancient seafaring in Eastern African Indian Ocean waters by Felix Chami pg 531-532, East African Archaeology: Foragers, Potters, Smiths, and Traders edited by Chapurukha M. Kusimba, Sibel B. Kusimba pg 89-97, Subsistence mosaics, forager-farmer interactions, and the transition to food production in eastern Africa by Alison Crowther et al. pg 101-120, Neolithic Pottery Traditions from the Islands, the Coast and the Interior of East Africa by Felix A. Chami pg 66-78)

Preliminary Report of the Re-excavation of Ukunju Limestone Cave in Juani, Mafia Archipelago, Tanzania by Abel D. Shikoni et al. pg 29-38, Sociocultural and economic aspects of the ancient Roman reported metropolis of Rhapta on the coast of Tanzania: Some Archaeological and historical perspectives by Caesar Bita et al.

Unguja Ukuu on Zanzibar: An archaeological study of Early Urbanism by Abdurahman Juma pg 28, Reinvestigation of Kuumbi Cave, Zanzibar, reveals Later Stone Age coastal habitation, early Holocene abandonment and Iron Age reoccupation by Ceri Shipton et al. pg 220-227)

Huffman, T.N. 2007. Handbook to the Iron Age: the archaeology of pre-colonial farming societies in southern Africa pg 335-359, Mapungubwe and the Origins of the Zimbabwe Culture by Thomas N. Huffman pg 15-16, Zimbabwe Culture before Mapungubwe: New Evidence from Mapela Hill, South-Western Zimbabwe by Shadreck Chirikure et al.

Archaeological excavations at Bosutswe, Botswana: cultural chronology, paleo-ecology and economy by James Denbow et al., The Iron Age sequence around a Limpopo River floodplain on Basinghall Farm, Tuli Block, Botswana, during the second millennium AD by Biemond Wim Moritz pg 6-7, 65, 234, The Origin of the Zimbabwe Tradition walling by Catrien Van Waarden pg 59-69

African Civilizations: An Archaeological Perspective By Graham Connah pg 306-309)

Munsa Earthworks by Peter Robertshaw, pg 1-16, A furnace and associated ironworking remains at Munsa, Uganda by Louise Iles et al.

African Civilizations: An Archaeological Perspective By Graham Connah pg 313-314, Munsa Earthworks by Peter Robertshaw pg 18)

African Civilizations: An Archaeological Perspective By Graham Connah pg 315-318)

African Civilizations: An Archaeological Perspective By Graham Connah pg 320)

Archéologie et anthropologie des tumulus de Kapanda (Angola) by M Gutierrez pg 148-150)

Archéologie et anthropologie des tumulus de Kapanda (Angola) by M Gutierrez

The Worlds of the Indian Ocean: A Global History Volume 1 by Philippe Beaujard pg 589, The East African Coast: Select Documents from the First to the Earlier Nineteenth Century by Greville Stewart Parker Freeman-Grenville pg 1-7)

The Swahili: Reconstructing the History and Language of an African Society By Derek Nurse, Thomas Spear, Swahili and Sabaki: A Linguistic History By Derek Nurse, Thomas J. Hinnebusch

Safari za Wasuaheli By Carl Velten pg 81-99, The Pate Chronicle edited by Marina Tolmacheva, A Revised Chronology of the Sultans of Kilwa in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries by Edward Alpers pg 154-160

Shanga: The Archaeology of a Muslim Trading Community on the Coast of East Africa pg 410, From Zinj to Zanzibar: Studies in History, Trade, and Society on the Eastern Coast of Africa in Honuor of James Kirkman on the Occasion of His Seventy-fifth Birthday by James S. Kirkman pg 136

Writing in Swahili on Stone and on Paper by Ann Biersteker pg 15-17

The Swahili: Reconstructing the History and Language of an African Society By Derek Nurse, Thomas Spear pg 93-94, Swahili and Sabaki: A Linguistic History By Derek Nurse, Thomas J. Hinnebusch, Gérard Philipson pg 617, East Africa: Kenya, Tanzania & Uganda, Volume 2 of The Afro-Asian nations: history and culture by Jan Knappert pg 262,

Afonso I Mvemba a Nzinga, King of Kongo: His Life and Correspondence By John K. Thornton pg 59, 235

Introducing a state-of-the-art phylogenetic classification of the Kikongo Language Cluster by Gilles-Maurice de Schryver et al. For kikongo words in 16th century manuscripts, see; Afonso I Mvemba a Nzinga, King of Kongo: His Life and Correspondence By John K. Thornton

The Kongo Kingdom: The Origins, Dynamics and Cosmopolitan Culture of an African Polity by Koen Bostoen, Inge Brinkman pg 60-61

The Kongo Kingdom: The Origins, Dynamics and Cosmopolitan Culture of an African Polity by Koen Bostoen, Inge Brinkman pgs 62-69, 98-99)

The Kongo Kingdom: The Origins, Dynamics and Cosmopolitan Culture of an African Polity by Koen Bostoen, Inge Brinkman pg 63)

French: From Dialect to Standard By R. Anthony Lodge pg 198-205

Language and Society in a Changing Italy By Arturo Tosi pg 5-14, In Italics: In Defense of Ethnicity By Antonio D'Alfonso pg 188

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa: Oral Traditions and History, 1400-1830 by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 55-65

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa: Oral Traditions and History, 1400-1830 by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 67-72)

The Bantu Expansion by Koen Bostoen (2018) pg 9

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 5, 10-15

The Bantu Expansion by Koen Bostoen (2018) pg 9

Very well written article

You absolutely slam dunked this one, wow! what a read I really appreciate your work.