Slavery in African History: New Perspectives on Its Dynamics, Legacy, and Historical Memory.

Voices of slavery in Africa: the 19th-century autobiographies of Nicholas Said and Dorugu.

In the early 19th century, the kachella (general) of the army of the empire of Bornu was Barca Gana, a man of servile origins who was the father of the American Union Soldier Nicholas Said; a globe-trotter who, from 1849-1860, travelled across the Maghreb, Arabia, Europe, and the Caribbean before settling in the United States.

Like Barca Gana, several of the most powerful officials in Bornu were slaves, including the chief tax collector, the chief administrator, and the governors and magistrates of most of its provinces and cities. Despite their slave origins, these men had wealth and power that most of their freeborn countrymen could only dream of. Barca Gana had thousands of followers, servants, and slaves; owned a large mansion in the capital, Kukawa; and was wealthy enough to afford the services of respected malams (scholars) who tutored his sons.1

The explorer Dixon Denham described Barca as a “black Mameluke… the sheikh’s first general, a negro of a noble aspect, clothed in a figured silk tobe, and mounted on a beautiful Mandara horse.” He mentions that Barca Gana “had fallen into the sheikh’s [al-Kanemi] hands, when only nine years of age, and had raised him with his fortunes, to the rank he now held as kaid, or governor, of Angala, part of Loggun, and all the towns on the Shary, besides making him kashella, or commander-in-chief of his troops.”2

As a general, Barca was involved in the many wars directed by the Bornu ruler, Sheikh al-Kanemi. The latter had rescued the ailing empire and its monarch from the newly ascendant Fulbe state of Sokoto (see map below), which had overrun its dependencies in Hausaland before invading Bornu. Numerous wars raged from 1808-1810, in which Bornu’s old capital of Ngazargamu was repeatedly sacked. Al-Kanemi was ultimately victorious, though he was forced to move the capital to Kukawa, which he founded in 1814.3

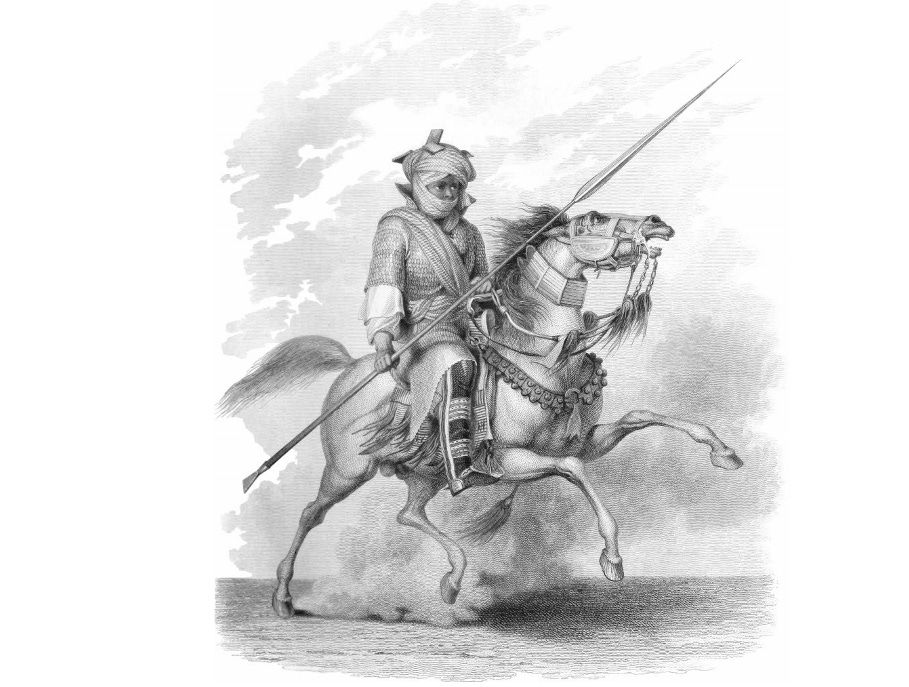

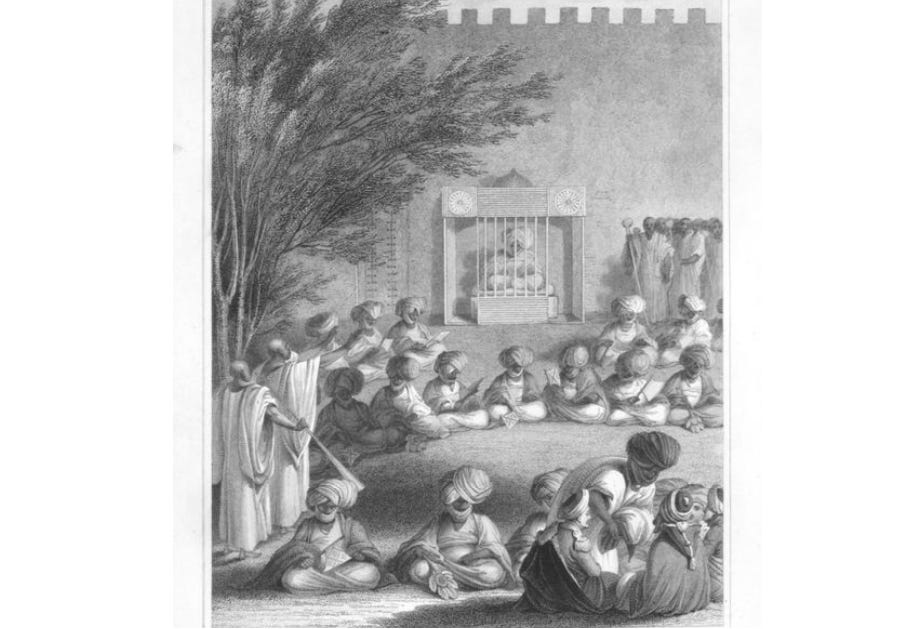

‘Body Guard of the Sheikh of Bornou’ engraving based on a sketch by Denham. 1826. The accompanying text suggests that this was a depiction of Barca Gana.

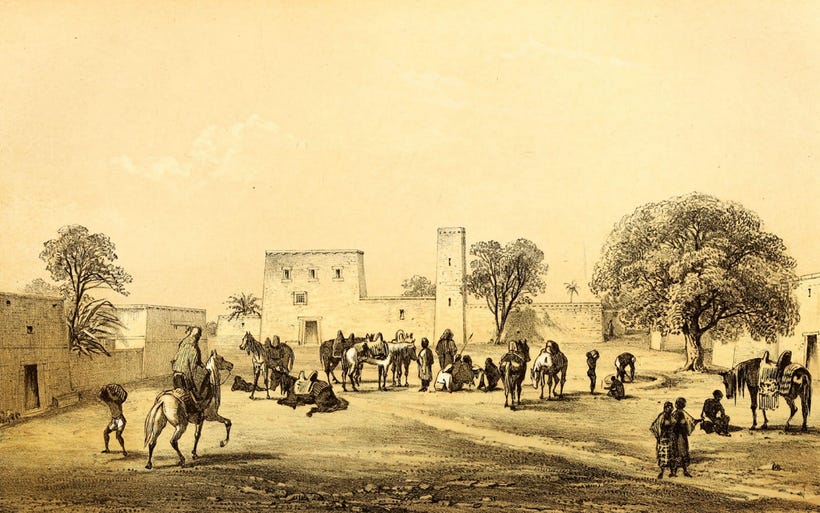

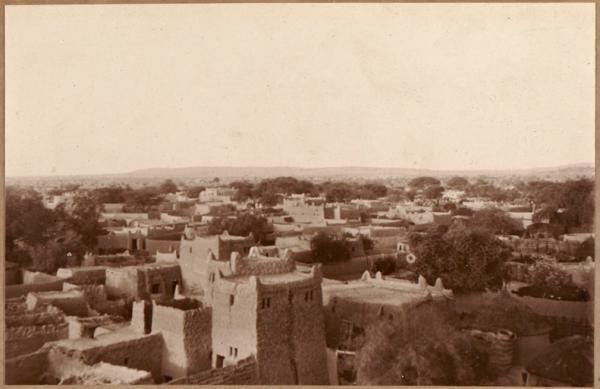

Kukawa, Nigeria. ca. 1857 by Heinrich Barth

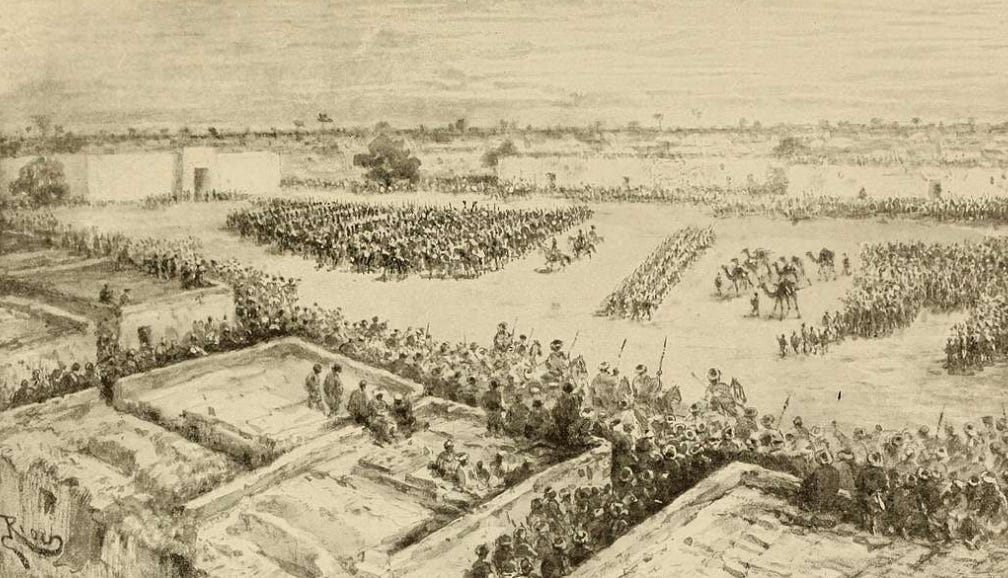

Reception of Monteil by Bornu’s courtiers, army, and spectators at Kukawa, Nigeria. ca. 1891.

West Africa in the 19th century, showing the empires of Sokoto and Bornu.

Having eliminated the threat from Sokoto, al-Kanemi began restoring Bornu’s hegemony across the region and pacifying the rebellious provinces, especially those populated by the Fulbe, who had thrown off their suzerainty to Bornu during the Sokoto wars. Some of al-Kanemi’s campaigns were therefore defensive, while others were offensive campaigns, yet all had clear political objectives.4

Despite its very early adoption of firearms, Bornu was not always the victor in these campaigns. Nicholas Said was enslaved when a group of Tuaregs, one of Bornu’s old foes, attacked him while he was in the countryside. In his autobiography, Said mentions that Bornu was ravaged by the armies of Sokoto, who took many war captives: “thousands upon thousands were sold to the [Atlantic] coast into bondage, and many more were sold to the Barbary States.”5

Contrary to popular interpretations of Bornu’s campaigns in Denham’s account as simple raids, these operations were not mere slave-catching razzias but genuine military engagements, whose political objectives were deemed important enough to justify the risk of losing substantial numbers of well-trained soldiers, horses, and firearms in battle. An example of this is the battle of Musfeia, where Denham nearly lost his life.

‘Attack on Musfeia’ ca. 1826. engraving based on a sketch by Denham

This particular battle was lost to Bornu, whose armies failed to take the well-defended ‘Fellatah’ (Fulbe) settlement of Musfeia in the south-western frontier of the Mandara kingdom along the Nigeria/Cameroon border.

Denham mentions that Bornu and Mandara had allied against their common enemy, the Fulbe, who, besides carving out their own large empire of Sokoto in the south-west of Bornu and subsuming its Hausa dependencies, had also overrun the southwestern Mandara province of Karowa, establishing themselves at Musfeia and Kora, thus significantly undermining Bornu and Mandara’s hegemony. Bornu’s army was crushed at Musfeia, many important officers and men were killed or captured, and Denham barely escaped with his life.6

While Denham and Barca Gana were fortunate enough to evade their captors, Nicholas Said wasn’t so lucky, since his captors were brigands, “who were constantly prowling through the country in search of anything of value they might lay their hands on.”

He was sold to multiple merchants until he reached Tripoli, where he learned that some of his companions who had been enslaved by the same brigands were later purchased to be freed by the Pasha of Tripoli once the latter was informed that they were sons of Bornu’s elites. Said almost earned his freedom this way, but his master didn’t let him, although he would later change his mind.7

The Pasha had, in fact, purchased Said’s companions to hold them for ransom, after which they would be redeemed by their relatives back in Bornu.

This was a common practice in the history of slavery across many societies, not just in Africa, but also in Asia and Europe. It was part of the diplomatic negotiations initiated after the conclusion of a major battle, and is especially well-documented for the 18th-century Barbary slave raids that targeted southern Europe. However, only a small fraction of slaves, about 5%, were ransomed. Most were not redeemed, but finished their lives as slaves.8

About two centuries earlier, in 1667, a similar series of conflicts between the Tuaregs of Agadez and Bornu resulted in the defeat of Bornu’s army and the capture of Sultan Alī b. ‘Umar’s nephew, [Medicon], who was ultimately sold in Tripoli. The Sultan of Bornu thus sent an embassy to the Pasha of Tripoli, requesting the latter to redeem his nephew, which he promptly did, giving him “clothes, servants and an apartment in the castle.”9

Said’s master in Tripoli fell into debt and tried to ransom him to the Bornu envoy in the city, but the latter had unfortunately gone away for some time, so Said was ultimately sold in Istanbul to the Ottoman official and ambassador Mehmed Faud Pasha (d. 1869). He later entered the service of the Russian prince Alexander Sergeyevich Menshikov (d. 1869) as a free man.

Said explains the nature of his freedom: ‘having never been “attached” to Russian soil, I could not be a serf under the “free” laws of that empire; and his excellency had notified me, on my arrival at the capital, that I was free, and at liberty to go whithersoever I chose.’10

Free to choose his employers, Said joined the service of another Russian nobleman, accompanying him across Europe, where he met a Dutch abolitionist, with whom he travelled to Canada and the Caribbean before settling in the US on the eve of the Civil War.

Comparing his experiences as a free man in the Southern United States during the 1860s to his time as a slave, Said writes that: “There seems to have been no prejudice among the Turks on account of complexion, their only prejudice being of a religious character. But in this country, and other enlightened Christian countries I have visited, the different denominations often carry matters to much greater extremes, indulging in back-bitings, open contentions, and, not seldom, actual oppression and persecution.”11

Back in Bornu, in the instances when its army was victorious, among those unfortunate to be on the receiving end of its successful campaigns was the kingdom of Zinder, which was nominally subject to Bornu but only paid tribute when the latter’s army was at its gates.

In 1849, Bornu’s sheikh Umar, successor of al-Kanemi, intervened in a succession dispute between Zinder sultans Ibrahim (r. 1843-1851) and Tanimun (r.1841-43, 1851-84). Initially, Bornu sided with the latter and sent its forces to sack the provinces allied with the former, such as Kanche. Shortly after Bornu’s army had left, Ibrahim returned to Zinder and deposed Tanimun. The latter then gathered a large force, expelled Ibrahim, and fortified Zinder.12

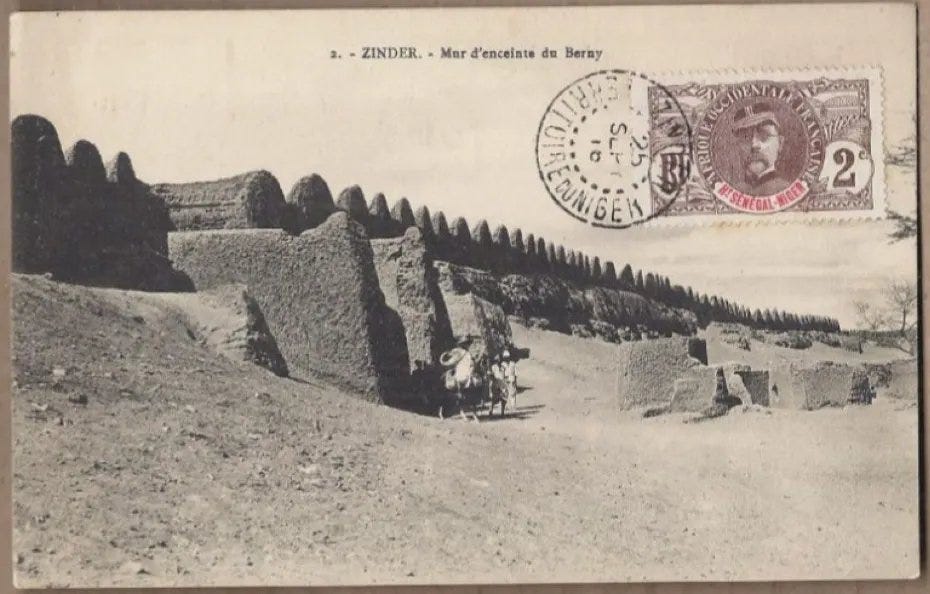

Walls and rooftop view of Zinder, Niger.

Ibrahim was compelled to move to Bornu, submitted to Umar, and requested his army to besiege Zinder and expel Tanimun, which the sheikh accomplished in 1843, restoring Ibrahim to the throne. Ibrahim’s submission came at a high price, because Bornu’s armies reportedly sacked the town of Dambanas in the province of Kanche, which had in the past haboured him as a rebel.

Bornu’s armies entered the walled town of Dambanas disguised as civilians, looted it, and seized many of its inhabitants as war captives, including the family of a Hausa boy named Dorugu, which was taken to Zinder as slaves, presumably to be ransomed back by their relatives, since they were Muslims and subjects of the Zinder sultan.

According to Dorugu’s account, his father was freed in Zinder by the sultan [Ibrahim], who instructed him to find the rest of his family and set them free. However, Dorugu’s father failed to find his son, who would remain enslaved, working as a household servant for different masters. He was given the Kanuri name ‘Barca Gana’ (little blessing) and was later sold at its capital Kukawa, before being freed in 1851 by the Kanuri servant of the German traveler Adolf Overweg. His status as a free man was only affirmed after obtaining a certificate of manumission from a Bornu official.13

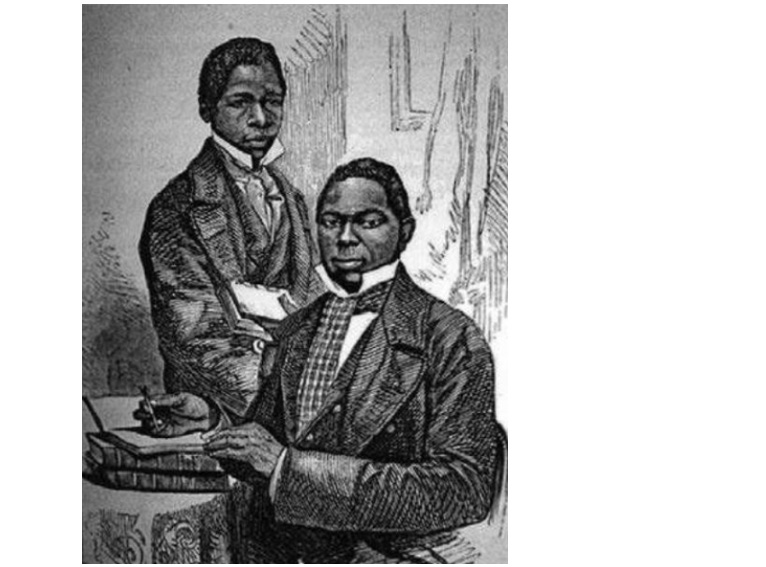

Drawing of the Hausa traveler Dorugu (standing) and Abbega (seated) in Hamburg, Germany, 1868.

Comparative study of slavery in Africa and the Black Sea region of Eastern Europe.

The above stories of Nicholas Said, Barca Gana, and Dorugu exemplified the wide range of life experiences of slaves in Africa, as well as the complex dynamics of slavery and freedom in the African context, and beyond the continent. They also demonstrate just how difficult it is to discuss slavery across a continent as large and complex as Africa.

Slavery, the nature of enslavement, and the shape of slaveholding societies changed over time, as did African ideas about freedom and belonging. The wide variation in the status of enslaved persons and the diverse ways in which they could obtain freedom demonstrate that the modern, binary opposition between ‘slavery’ and ‘freedom’ is inadequate for describing the continuum of dependent statuses that shaped social life in pre-colonial African societies, and in much of the Old world before the 19th century.

As the historian David Eltis explains in the introductory chapter of ‘The Cambridge World History of Slavery’:

“However firmly the modern mind sees free labor as the antithesis to slavery, free labor arguably did not exist at all until the nineteenth century… a definition of free labor in the modern sense would have covered few, if any, waged workers in 1750 or in any preceding era. The vast majority of people in most societies in history have been neither slave nor free, once we consider the limited rights to political participation that existed, and not just freedom from labor coercion.”14

An example of the seemingly contradictory nature of slavery in the Old World is the term “Mamluke” (ie, mamlūk), which Denham used to describe Barca Gana, referring to a specific group of slaves in the Islamic world who were groomed to become soldiers. The best known of these was the Mamluk dynasty, which ruled Egypt and Syria ca. 1250-1517, but there are numerous examples of such Mamluks across the Islamic world from medieval Northern India to Yemen and Spain.15

Mamluks were originally purchased as slaves, usually acquired in their youth as victims of wars in eastern Europe and central Asia, converted to Islam, and raised together in barracks where they received rigorous training. Once completed, they were manumitted and appointed to posts in the lower ranks of the army and the court, from where a few may rise to become powerful rulers.16

The Mamluk rulers would, in turn, import large volumes of slaves from their homeland in order to grow their armies. In the late Middle Ages, most enslaved persons from the black sea region were purchased from slave merchants via the rich port cities of southern Europe. Most were enslaved in their youth since men were usually killed in battle. The girls were kept as domestic slaves while the boys were sold abroad.17

Slave Trade routes in the eastern Mediterranean. Map by Hannah Barker.

From the 16th to the early 19th century, enslaved persons from eastern Europe and captives taken by Barbary raids on southern Europe were sold across the Ottoman domains. The dynamics of warfare, conflict, and trade that fueled this trade were incredibly complex (eg, many of the Barbary slavers were themselves European). Once enslaved, some became janissaries, others were retained as domestic slaves, some as eunuchs and concubines, and others as galley slaves.18

The volume of this trade was significant; an estimated 2,000,000 slaves were “imported into Ottoman lands from Poland-Lithuania, Muscovy and Circassia” from 1500 to 1700. These figures dwarfed the Atlantic slave trade from the entire coastline of Africa at the time, which was estimated at 1,800,000.19

Its demographic impact was equally significant. Eltis notes that “there may have been more English slaves held in North Africa than black slaves in the English Caribbean in the second half of the seventeenth century.”20 However, their treatment and occupation would have been significantly different, being closer to the experiences of Nicholas Said and Dorugu, than to the brutal exploitation of plantation slaves.

This brief comparative study of slavery in north-central Africa and the Mediterranean world reveals the diverse yet shared nature of unfree labour in the Old World. Similar forms of ‘slavery’ existed across East and South Asia, which won’t be included here for the sake of brevity, but are sufficiently explored in ‘The Cambridge World History of Slavery’ series.

While we must acknowledge the complex nature of slavery in the Old World, it’s important to note that slavery was regarded across most cultures at best as an unfortunate/undesirable fate, and at worst as the ultimate degradation for any human being, often described as a form of “social death.”

Virtually all enslaved persons were acquired through violence, their agency was constrained, and only a fraction of them were freed. Voluntary enslavement was rare, but slave rebellions were common. As the autobiography of Nicholas Said makes it clear, when given the choice, enslaved persons would have preferred to return to their families.

For most readers, slavery evokes images of men labouring on cotton or sugar plantations under harsh conditions, held in perpetual servitude as chattel with few if any legal rights and even fewer opportunities for freedom. The trans-Atlantic slave trade from Africa and the growing share of enslaved Africans in the Islamic world during the 19th century also meant that race and slavery became ideologically linked.

These central features of American slavery, such as perpetual servitude, severe exploitation for economic gain, and the emergence of a distinct caste or racialised class of slaves at the bottom of the social hierarchy, became the yardstick by which other forms of slavery are measured.

However, as the following analysis will show, slavery in Africa, much like in broader regions of the Old World, was a fundamentally different institution from that found in the Americas.

This essay explores the dynamics and legacy of slavery in Africa, focusing on the societies that were linked to the Atlantic world.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by joining our Patreon community. Subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Who were slaves in Africa? ‘unfree’ labour and legal protections against enslavement in Africa.

The historiography of slavery and the slave trade is heavily constrained by the conceptual vocabulary used to describe it. Our understanding of the institution of slavery in modern scholarship is mostly derived from a Western semantic structure that has been applied universally without recognition of its inherent limitations.21

The English language has only two words; slave and serf*, to indicate a person of unfree status. On the other hand, medieval Latin had a broad range of words: servus, sclavus, mancipium, colonus, villanus, emtitus, famulus, verna, ancilla. Similarly, the Arabic language has several words such as ‘abd, raqīq, ghulām, fatan, khādim, mamlūk, waṣīf, jāriya, and ama.22

*after the decline of slavery and serfdom in western Europe during the early modern period, they were replaced with other coercive forms of labour, such as penal and indentured servitude, that were only slightly less coercive. Serfdom persisted in other parts of Europe, especially in Russia, well into the 19th century.23

The terms used to describe ‘unfree’ labor were not interchangeable but denoted distinct social categories with differing legal rights. This distinction is particularly important for understanding slavery in Africa, since most descriptions of the institution come from European travelers in the 19th century who transplanted their own concepts to African social systems, but were often unfamiliar with the complex social systems they described.24

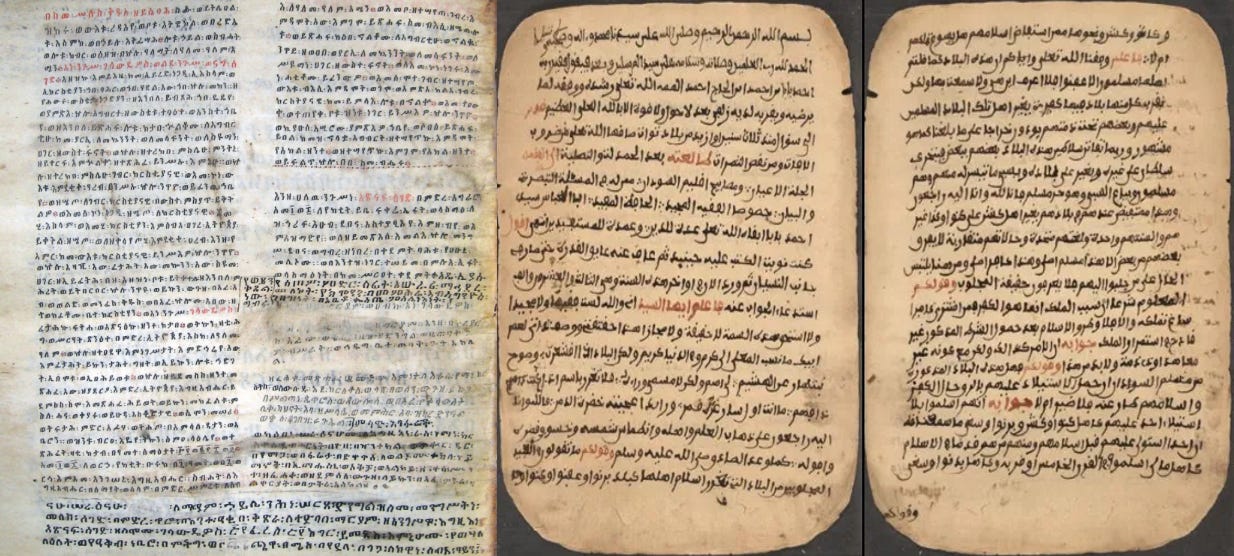

internal accounts on slavery in Africa. (left) Fatwá on the rulings of slaves in war. 19th century. Bibliothèque de Manuscrits al-Imam Essayouti, Timbuktu, Mali. (right) No. ELIT ESS 04014. Letter to the Emir of Hayre Ḥāmid ibn Aḥmad Lobbo regarding the ownership of certain slave lineages. 19th-20th century. Bibliothèque al-Cady al-Aqib, Timbuktu, Mali. No. ELIT AQB 01268. images from HMML Reading Room with the permission of SAVAMA-DCI.

In the Atlantic world, interactions between different societies reshaped the terminology of slavery. The English and Dutch initially used the term ‘negro’ as an ethnonym, which by the 17th century came to refer specifically to enslaved individuals in perpetual dependence. In contrast, the Portuguese used the terms ‘escravos’ and ‘pecas’ (pieces) interchangeably with ‘negro’ to denote enslaved Africans in perpetual servitude. 25

There are a handful of African societies in the Atlantic world that produced literature on slavery, such as the kingdoms of Kongo and Ndongo in what is today Angola.

Documents from 16th-century Kongo and 17th-century Ndongo, which were written by local scribes in the Portuguese language, refer exclusively to war captives who were exported as ‘pecas’ or ‘spravos [escravos]’. In both Kongo and Ndongo, the ‘pecas’ were known locally as Mvika/Mubika, and were distinguished from other dependents called quizicos [kijiko], who couldn’t be exported and enjoyed a higher status than the former.26

The Kijiko/Kijuku/Ijuku were originally captives who had been settled on lands and were inalienable though servile. They formed communities in settlements that were governed by a free person designated by the king. They provided key political and military support to the governing elite and were so powerful as to participate in the process of selecting kings.27

This separation between different groups of dependents in Kongo and Ndongo highlights the complexity of slavery in West-Central Africa, where laws and cultural norms governed interactions among different social groups, from the nobles ( who appear in internal documents as ‘fidaglo’/soba’), to the citizens (‘naturaes forros’/ana murida), to the ‘dependents’ (kijiko) and ‘slaves’ (Mvika/Mubika).28

The rulers of Kongo and Ndongo enforced these laws to protect their free subjects from enslavement and regulate the slave trade. Kings established courts of inquiry to investigate illegal enslavement, including questioning each trader to determine the origin of each slave,29 and went as far as to repatriate thousands of illegally enslaved citizens from Brazil twice in the 1580s and 1620s —without paying ransom/compensation to the slavers.30

Similar social hierarchies and legal frameworks governing the status and rights of different groups existed across multiple African societies that determined the authority that a person or group could exercise over others. Typically, these rights were embedded in complex exchanges covering not just slavery but all manner of social institutions like kinship, inheritance, marriage, forming part of a broader network of exchanges involving labor, property, and money.31

This complicates our understanding of the nature of slavery within African societies, as the way in which such exchanges/transfers occurred and how the people involved in the transfers were treated contradicts simplistic binaries of “free” and “enslaved” persons. In many Atlantic African societies, ‘freedom’ was defined either by membership in a social group capable of securing an individual’s legal and social rights as an ‘insider’ or by affiliation with a powerful figure who could provide the same.32

It’s for this reason that many African states had laws against the enslavement of some groups, while permitting it for others. Examples of direct evidence for pre-colonial African laws regarding enslavement have been found in societies where internal documentation was fairly common, such as in Ethiopia and West Africa.

In Ethiopia, an edict by King Gälawdéwos in 1548 expanded pre-existing protections against the enslavement of Ethiopian-Christian subjects, while also regulating the trade by requesting that regional governors determine the status of enslaved people before export:

“If the seller who [knowingly] sold a Christian is a merchant, whether he be Muslim or a Christian Ethiopian compatriot, let them kill him. If an Arab [merchant] knowingly purchases a Christian, let them confiscate all his property. Any azaj (commander or chief), whether he be fätahit (judge), or mäkonnen, or seyum of the district, who [slacks on his obligation] and does not follow our commands, deserves to be killed without mercy and his house ransacked.

I, King Gälawdéwos, legislated this law and sanctioned this writing.”33

Nearly a century later, Emperor Susneyos (r. 1607-1632) commanded that his subjects should have no dealings in [Christian] slaves with Muslims or Ottomans. He reportedly executed a rich Muslim trader found guilty of exporting slaves from Enarya, and had his head stuck on a pole in the marketplace as a warning to others. He summoned his governors and ministers of the court and instructed them on pain of severe penalty.34

But, as with any law, there was always a gap between legal status and actual practice, which fluctuated depending on the coercive power of the state. Ethiopian captives, including Christians, could be found among the enslaved persons both within the country and in the Red Sea world. There were, however, accorded a certain degree of protection in the highlands, where they could be ransomed.35

In the West African city of Timbuktu, the 17th-century treatise of the scholar Ahmad Baba titled Miraj al-Suud ila nayl Majlub al-Sudan (The Ladder of Ascent in Obtaining the Procurements of the Sudan), outlines the laws protecting free Muslims of various ethnicities from enslavement; the protections offered to non-Muslim subjects [dhimma], and those ethnicities whose war captives could be legally enslaved.36

(left) The 16th-century edict of Gälawdéwos at the Tädbabä Maryam church, Ethiopia. (right) Copy of Ahmad Baba’s 17th-century treatise on slavery. Library of Congress

The numerous references to the repatriation and ransoming of ‘illegally enslaved’ African Muslims, especially from Bornu, as early as the 14th century, indicate that such religious protections were respected.37 Ransoming of war captives doubtless existed between West African Muslim states as well, as mentioned in Dorugu’s account. Court records from Ottoman Egypt during the 19th century include accounts of several illegally enslaved African Muslims who successfully sued for their freedom, often with the help of other African Muslims who were visiting Cairo.38

Some of these visitors would have been African envoys or monarchs, as mentioned in Nicholas Said’s account and the 1667 Bornu embassy to Tripoli, which freed the sultan’s nephew.

Another account from 1655 mentions that the Sultan ‘Alī b. ‘Umar (1639-1677) of Bornu was reportedly denied entry in Tripoli by the Pasha for fear of having to free the “negro slaves, subjects of this prince or his allies”, as well as his fear “that the Arabs would take the opportunity to revolt against him, seeing in their country an African king who lived in the opinion of holiness among the Mahometans.”39

Incidentally, this account came from a Frenchman who had been enslaved in Tripoli. And while the Bornu sultan was discouraged from visiting the city, he sent his ambassador in the same year, who stayed a month in Tripoli, and delivered an official letter to the pasha containing a request from the Bornu sultan for another consignment of European captives for his army.40

An account by an enslaved Belgian in Agadez (Niger), named Pieter Farde, who had been captured by Barbary pirates in 1687, documents the presence of several European Christian and Jewish slaves in Agadez, including a Frenchman named Louis de la Place, who was their foreman and mistreated them. Their situation was less ideal than the European Mamluks of Bornu, who, according to the sultan Alī b. ‘Umar, had developed a “high reputation for valor and skill.”41

The existence of legal protections against enslavement for different social groups in pre-colonial Africa, and the two-way traffic in captives between West Africa and the Maghreb, suggests that the operation of the slave trade across the Old World was enabled by the existence of broadly similar political, economic, and social institutions for organising multiple forms of labour in the pre-modern world.

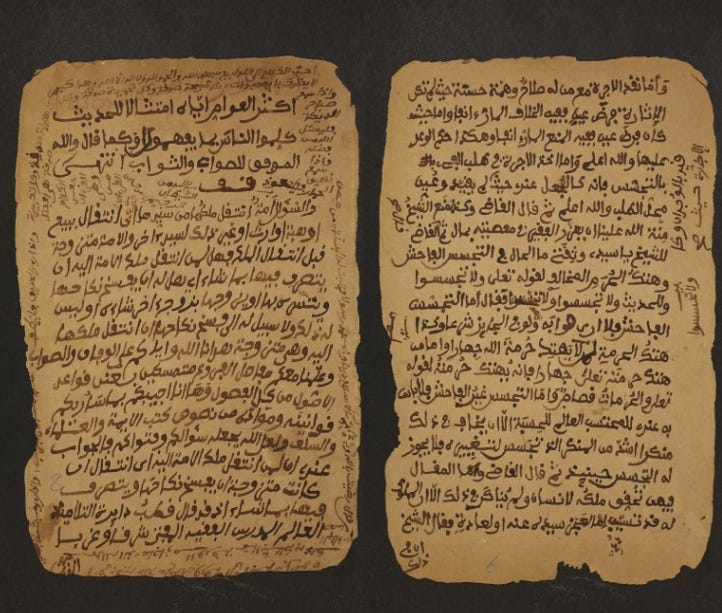

‘Proclamation putting an end to the practice of rulers seizing Bambara and other local unbelievers as slaves without formal capture or purchase’ written by Ahmad Lobbo (d. 1845). Mamma Haidara Library, Timbuktu. Mali. images from HMML Reading Room with the permission of SAVAMA-DCI, No. SAV BMH 35085.

Why were there slaves in Africa? Social complexity and the origin of domestic and military slaves.

Map showing the 17th-century kingdoms of Africa’s Atlantic coast, highlighting the kingdom of Kongo. Map by J.K.Thornton

At its core, slavery in Africa emerged from the interplay of diverse social and economic systems operating within the continent’s shifting political landscape. It did not arise in response to external demand from beyond the continent, nor from the commercial exploitation of labour characteristic of the Americas, although similar systems did eventually emerge in some parts of the continent.42

The regions of west and central Africa, for example, were dotted with numerous states and societies of varying sizes, ranging from large empires like Songhai to medium-sized kingdoms like Asante in modern Ghana to small societies like the Aro confederacy of southeastern Nigeria.43

In small-scale societies such as the Vai of Liberia and the Imbangala of Angola, where kinship systems were the primary forms of social organization, the acquisition of outsiders as ‘slaves’ was driven by multiple demands, including the need to increase kin group members, followers, and dependents, as well as supplementing agricultural/subsistence labour.44

In many parts of Atlantic Africa, the formation of states like the kingdoms of Loango and Kongo emerged in the processes of concentrating wealth and power, as claims over resources by pre-existing lineage groups merged and overlapped with claims made on behalf of states by powerful figures or ‘big men’.45 Once large kingdoms like Asante were established, participation in the office-holding structures of the state became the key to the accumulation of these resources, as well as their control and redistribution.46

The rulers of these states combined multiple forms of legitimacy to expand their power, including military prowess, like in the Segou empire (whose military system and slave rulers resembled the Mamluks), 47the promotion of religious customs in kingdoms such as Allada and Dahomey,48 and the ability to attract or acquire followers and concentrate them around major capitals, like the monarchs of Kongo.49

The ruler’s power was often checked by other powerful ‘councilors’ in parliaments, for kingdoms such as in Kongo, Loango, Benin, Warri, and Asante. These councilors chose the king from a pool of candidates and determined his ability to tax, raise armies, and regulate trade.50 Kings would at times counter-balance the authority of the council by raising their own armies of military slaves and appointing slave officials, eg, in the empires of Bornu and Sokoto.51

Reception of Dixon Denham at the court of the Shehu (Sheikh/Ruler) of Bornu. ca. 1822-4, Kukawa, Nigeria.

How did they become slaves? Warfare and the story of the Antonian slaves from Kongo.

In most complex societies, the extended processes of state formation and territorial expansion gave rise to institutions such as judicial mechanisms for adjudicating disputes, fiscal systems for collecting taxes and tribute to facilitate resource redistribution, titled officials responsible for administering governmental affairs, and military systems for defense and the projection of power.52

These processes entailed the transfer and accumulation of rights, resources, followers, and dependents, thereby generating enslaved persons, many of whom were retained domestically, while some were exported to regional and global markets.53

Documentary evidence indicates that both inter-state and intra-state warfare supplied the majority of enslaved people exported into the Atlantic world, yet the motivations driving these conflicts were varied, ranging from territorial expansion and evolving political alliances to the control of economic resources.

In the 17th-century Portuguese colony of Angola, which is one of the few cases where Europeans gained a foothold in Atlantic Africa, their military campaigns were driven less by the direct pursuit of slaves than by ambitions of territorial expansion and resource extraction. Yet many war captives were enslaved and exported as a consequence of the wars, despite the 1607 legislation stipulating that enslaved persons could be obtained only through “just war.”54

The same dynamic of territorial expansion and resource exploitation influenced Portuguese colonial policy in the kingdom of Mutapa (North-Eastern Zimbabwe) during the 17th century. But unlike Angola, this region exported relatively few enslaved people, as most were retained locally to labor in the gold mines.

In the kingdom of Dahomey, written correspondence between its royals and the Portuguese colonists in Brazil reveals that the former’s military campaigns were primarily defensive in nature, with slaves only being a byproduct, along with other spoils. This corroborates the declarations made by Dahomey kings, who told visiting British envoys that: “Your countrymen, who allege that we go to war for the purpose of supplying your ships with slaves, are grossly mistaken.”55

In the kingdom of Kongo, the objectives of most of its wars were primarily political in origin, such as its conflicts with the province of Soyo and the Portuguese of Angola, and the defensive wars against the Jaga and Imbangala war bands, all of which generated followers, dependents, and slaves for their leaders.56

When Kongo fragmented during the late 17th century, old provinces became sovereign states with rulers who felt no obligation to extend the protection their subjects enjoyed to others whom they now considered enslavable. This resulted in an influx of enslaved baKongo in the Atlantic world, especially after the Antonian movement Princess Beatriz Kimpa Vita, when catholic baKongo citizens began to appear in American plantation colonies.57

The documentary evidence from this period of the Kongo illustrates the complexity of the relationship between politics, war, and slavery. The kingdom and its people were familiar with the horrors of slavery, especially during the Civil War that raged from 1665-1709. The prospect of being embarked on slave ships and cannibalized** by Europeans terrified them, prompting many slaves to escape from Luanda.58

**contrary to popular literature which links the widespread African belief of European cannibalism to the slave trade59, records from other parts of the continent outside the Atlantic world, which also associated ‘Europeans’ with cannibalism, indicate that it was likely a common stereotype attached to foreigners, not unlike the one Europeans had about Africans. In his first meeting with Adolf Overweg in 1851, Dorugu mentions that he was terrified of the German, whose “face and hands were all white like paper. He was looking me over. I was as afraid as if he were about to eat me.” In 1854, at the far end of the continent, the Englishman Richard Burton reported encountering a group of Somalis near Zeila who reacted with shrieks upon seeing him.: “The white man! the white man! run away, run away, or we shall be eaten!”)60 In south-Africa, during the 16th and 17th century, records of shipwrecked portuguese crewmen cannibalising africans they found on the beach suggest that these were more than just myths.61

The Antonian followers of Princess Beatriz must have known the risks of joining her movement, which was considered heretical by the clergy. The movement’s illegal occupation of the old capital São Salvador [Mbanza Kongo] also threatened the authority of the Kongo king Pedro IV Nusamu a Mvemba, who was determined to unify the kingdom, even after his captain-general, Kibenga, had sided with the Antonians. A series of skirmishes from 1705-1708 ended with a climactic battle near the old capital in 1709 that saw the defeat of the Antonians.

As heretics with no hope of royal mercy, nor military protection (unlike Kibenga’s forces), an estimated 2-5,000 Antonian captives were sold as slaves in Luanda from 1707-9, and 1714-1715, from where they were shipped to Brazil. A full year before the final battle, a visiting priest who traveled on the same slave ship transporting the Antonians to Brazil documented the appalling conditions on board, and was undecided whether their unfortunate situation could best be compared to Hell or Purgatory.62

This tragic fate of the Antonian captives and the political-religious objectives that drove their wars with Pedro IV were quite similar to what Bornu’s soldiers faced during their campaign against the Fulbe town of Musfeia. In both cases, the people who engaged in those conflicts thought that their political objectives outweighed the risk of defeat and capture.

War captives were mostly a byproduct of political conflict rather than its primary cause, and their ultimate fate was determined by a range of factors, as summarized by the Sokoto ruler Uthman Fodio: “The fate of captives is determined by the victor. As for the men, the Imam (Caliph) has to make a choice between five things: to kill them, to set them free, either by grace or ransom, to make them pay jizya (tax), or to enslave them.”63

Besides warfare, the punitive enslavement of criminals was common for crimes such as murder, theft, witchcraft, or sale to clear debts.64 slaves were also generated through kidnapping, such as in the case of Olaudah Equiano from the Benin kingdom, or as a product of religious proceedings, eg, in the Aro confederacy,65 or through voluntary enslavement during periods of crisis in west-central Africa.66

When did slavery end? Abolition in African history.

The official abolition of all forms of slavery that began with Haiti in 1804, followed by Britain in 1833, marked the start of a shift in political and economic relations between societies in the Atlantic world.

Although the ideology of abolition in Britain emerged from the economic and social transformations in the country during the late 18th century, the processes of abolition and emancipation were never solely the triumph of British ideals; rather, they were co-constructed by a cosmopolitan network of actors across Africa, the Americas, and Europe, each responding to local conditions and the expansion of Britain’s political reach into their territories.67

Research from the Senegambia region shows that the decline in slave exports began much earlier than the abolition and was largely influenced by increased domestic demand.68 In the Gold Coast region, recent studies suggest that it was Asante’s sudden withdrawal from the slave export market rather than the weak British patrols that explain the decline in slave exports from the region.69

A more detailed study of the economic transition of Atlantic African societies from the export of slaves to the export of commodities like palm oil suggests that it was “a relatively smooth process” for the kingdoms of Asante and Dahomey and that both states were successful in “accommodating to the changing commercial environment.”70

Many of the same institutions that regulated the social institution of slavery also influenced the process of emancipation in pre-colonial African societies. The transition from ‘slavery’ to ‘freedom’ was attained through manumission, revolt, or escape. Most involved an enslaved person’s withdrawal from their master and their kin group, and the process of acquiring new social groups or patrons.71

For example, in 19th-century Kongo, a ‘slave’ was redeemed by being bought back by his own natal lineage, and became their dependent, while the ‘slaves’ of the Tuareg went through successive physical withdrawals from their desert-based masters into the sedentary Hausa communities until they were incorporated into local ethnic groups.72

These processes of emancipation were also influenced by political factors, some of which pre-dated the 19th century, such as the aforementioned anti-slavery laws in Kongo, Ethiopia, and West Africa, and the various ways in which people who were illegally enslaved were repatriated in Kongo, or sued for their freedom in Islamic courts.

However, the widespread abolition of slavery largely occurred only when European imperial ambitions intersected with abolitionist ideology, and even then, its implementation varied, with some forms of slavery continuing well into the post-war era.73

In many parts of Africa, emancipation during the colonial era involved a slow process of readjustment in which traditional social systems were supplanted by new forms of dependency, either to host societies or to the colonial government as forced or contract labourers. In French West Africa and Italian Somalia, many former ‘slaves’ opted to leave en masse, undermining the delicate political and economic arrangements that colonial administrators sought to preserve by delaying the implementation of abolition.74

The abolition process accelerated during the late colonial period primarily due to the economic opportunities available to former ‘slaves’ and their masters. The geographically uneven spread of commercial agriculture enabled some former ‘slaves’ to become cash crop farmers or migrant labourers. Former slave-owners in regions conducive to the cash crop farming became employers, while those outside the more productive regions saw their wealth, status, and households shrink.75

The social effects of abolition were no less varied than its political and economic ramifications.

In regions such as south-eastern Nigeria, where former ‘slaves’ were integrated, settlement patterns varied from mixed villages and towns where freed-slaves were integrated to clearly segregated settlements where freed-slaves lived apart from host communities. In both settlement patterns, modern conflicts and legal disabilities are at times linked to the dynamics of slavery and abolition in the 19th century.76

Following the consolidation of political power by colonial and post-colonial governments and the criminalization of slavery, the social status of former slaves became increasingly independent of their kinship ties, as these groups no longer retained coercive authority over their former dependents beyond that exercised over their own members. This has led to a shift in the perspective of slavery among both the kin group members and former ‘slaves’, giving rise to multiple, sometimes contradictory, understandings of slavery across Africa.77

Conclusion: Contested Legacies of Slavery in Pre-Colonial Africa

Given the absence of a singular, coherently defined form of “African slavery,” different social institutions produced a variety of outcomes that should be understood as existing along a continuum of social relations, from those regarded as kin to those treated as chattel.

These varied forms of ‘slavery’ both influenced and were influenced by multiple social, economic, and political factors that were largely endogenous to Africa, while resembling comparable systems of slavery in the Old world, thereby facilitating the transfer/sale of those considered to be ‘slaves’ from Africa to other parts of the world.

However, unlike the Americas and Europe during the 19th century, the fluidity of Africa’s political landscape rendered all social categories highly malleable, leaving no distinct class or caste of slaves.

In the 19th-century empire of Segu in Mali, the Bambara rulers, Marka traders, and Somono boatmen represented relatively recent and heterogeneous social groups. ‘slaves’ were present across all social groups, from the slave dynasty of Diara/Jara which ruled the empire, to military slaves, to plantation slaves working for the Marka, to the enslaved boatmen who were joined to the Somono. This complex social system collapsed once the empire was defeated by Umar Tal in 1861, and was replaced with different social structures.78

Former military slaves could seize power and become kings, women who had been enslaved as concubines could become matriarchs of free lineages, kingdoms that concentrated enslaved dependents in their capitals could collapse and be transformed into new states ruled by ex-slaves.

Consequently, only the most recent iteration of slavery and other social relationships was considered significant at the time of abolition during the colonial period. For this reason, contemporary African memories of slavery are largely shaped by colonial discourses of abolition and imperialism, which were carried over to the post-colonial period. (eg, in the myth of the so-called ‘house of slaves’ in Goree, Senegal)

Images of slave raids on villages, gangs of captives being driven to the coast, and the supposedly benevolent colonial officer breaking slave chains, reveal more about the intentions of those who produce the images than about the historical reality of slavery in Africa.

While it may never be possible to write a history of African slavery that truly satisfies the historian’s inordinate greed for both generalization and specificity, this essay should hopefully serve as a useful introduction to the complex and diverse history of the institution of slavery in pre-colonial Africa.

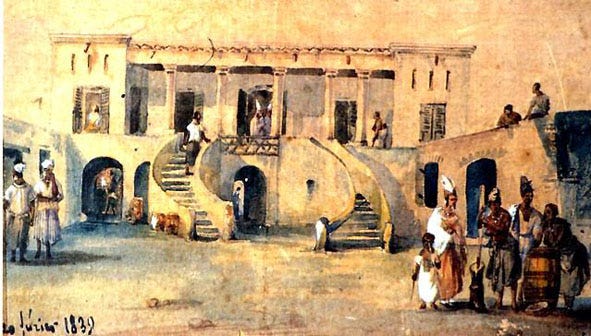

View of the inner courtyard of the house known as Anna Colas’s, currently called ‘Maison des esclaves’ (House of Slaves). February 20, 1839. Image by Xavier Ricou.

The so-called house of slaves, which is now a major tourist site that has been visited by three US presidents, was a fabrication by its curator, Joseph Ndiaye, who claimed that 10-15 million enslaved Africans were trafficked through its ‘door of no return’. In reality, the entire island of Goree never exported more than a few hundred slaves a year, according to the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Data Base, and hardly any of them would have gone through this rather unimportant house: “The pathetic idea of a door through which slaves supposedly passed on their way to America was nothing but a story intended to impress tourists at the end of the 20th century.”79

In 1555, the Ottomans installed a garrison of slave-soldiers from Eastern Europe at the port town of Suakin in Eastern Sudan, which was described by the Portuguese as one of the greatest towns in the Middle East.

By 1814, the small Turkish garrison had been acculturated into the local society: “many of them assert that their forefathers were natives of Diarbekr and Mosul; but the present race have the African features and manners, and are in no respect to be distinguished from the Hadherebe (ie, Ḥaḍāriba).”

The history of Suakin is the subject of my latest Patreon article. Please subscribe to read about it here and support this newsletter:

The Sergeant: The Incredible Life of Nicholas Said: Son of an African General, Slave of the Ottomans, Free Man Under the Tsars, Hero of the Union Army by Dean Calbreath

Narrative of travels and discoveries in northern and central Africa by Dixon Denham

Attempts at Defining a Muslim in Nineteenth Century Hausaland and Bornu” by D. M. Last and M. A. Al-Hajj

Studies in West African Islamic History: Volume 1: The Cultivators of Islam, Volume 2: The Evolution of Islamic Institutions & Volume 3: The Growth of Arabic Literature by John Ralph Willis, pg 160-167

The Autobiography of Nicholas Said: A Native of Bornou, Eastern Soudan, Central Africa by Nicholas Said, pg 8, 21.

Narrative of Travels and Discoveries in Northern and Central Africa: In the Years 1822, 1823, and 1824, Volume 1 by Dixon Denham, Hugh Clapperton, Walter Oudney, published by John Murray, 1826, pg 157-160.

The Autobiography of Nicholas Said: A Native of Bornou, Eastern Soudan, Central Africa by Nicholas Said, pg 39-40

The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 2, AD 500-AD 1450 edited by David Eltis, et al., pg 53-75, The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 3, AD 1420-AD 1804 edited by David Eltis, Stanley et al., pg 144, 153-154, American Slaves and African Masters: Algiers and the Western Sahara, 1776-1820 By C. Sears, pg 20-21.

Du lac Tchad à la Mecque: Le Sultanat de Borno et son monde (xvi e –xvii e siècle), by Rémi Dewière pg 185

The Autobiography of Nicholas Said: A Native of Bornou, Eastern Soudan, Central Africa by Nicholas Said, pg 73

The Autobiography of Nicholas Said: A Native of Bornou, Eastern Soudan, Central Africa by Nicholas Said, pg 37

This description of Zinder’s politics comes from the account of the German missionary Sigismund Koelle based on information he obtained while in Sierra Leone in the 1850s. It’s similar to Dorugu’s first-hand account, especially regarding Bornu’s attack on Kanche, described in his autobiography, which was completed in 1857, although the two writers never met.

West African Travels and Adventures. Two Autobiographical Narratives from Nigeria., by Anthony Kirk-Greene and Paul Newman. pg 38-39, 47-49)

The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 3, AD 1420-AD 1804 edited by David Eltis et al. pg 3, 11)

for a broad outline on military slavery in the medieval islamic world see; chapter 4-5, and 14-16 in The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 2.

The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 2, AD 500-AD 1450 edited by David Eltis, et al., pg 100-118, Slavery in the Black Sea Region, c.900–1900: Forms of Unfreedom at the Intersection between Christianity and Islam, Felicia Roșu (ed.)

That Most Precious Merchandise: The Mediterranean Trade in Black Sea Slaves, 1260-1500 by Hannah Barker. Slavery in the Black Sea Region, c.900–1900: Forms of Unfreedom at the Intersection between Christianity and Islam, Felicia Roșu (ed.)

The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 3, AD 1420-AD 1804 edited by David Eltis et al., pg 141-158

Slave hunting and slave redemption as a business enterprise by Dariusz Kołodziejczyk. pg 151-152.

The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 3, AD 1420-AD 1804 edited by David Eltis et al., pg 16)

Slavery in Africa: Historical and Anthropological Perspectives by Suzanne Miers and Igor Kopytoff (eds.) pg 77-78

That Most Precious Merchandise: The Mediterranean Trade in Black Sea Slaves, 1260-1500 by Hannah Barker, pg 14- 15

The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 3, AD 1420-AD 1804 edited by David Eltis et al., pg 135-140, as well as Chapters 11-12, 23-24.

Slavery in Africa: Historical and Anthropological Perspectives by Suzanne Miers and Igor Kopytoff (eds.), pg 50

Central Africans, Atlantic Creoles, and the Foundation of the Americas, 1585-1660, by Linda M. Heywood, John K. Thornton, pg 315-323

Abolitionism and Imperialism in Britain, Africa, and the Atlantic, by Derek R. Peterson (ed), pg 47-50, Njinga of Angola: Africa’s Warrior Queen by Linda M. Heywood, pg 40, Afonso I Mvemba a Nzinga, King of Kongo: His Life and Correspondence by John K. Thornton, pg 75

The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 3, AD 1420-AD 1804 edited by David Eltis et al., pg 112

Slavery and its Transformation in the Kingdom of Kongo by Linda M. Heywood, pg 4-5

Derek R. Peterson (ed) Abolitionism and Imperialism in Britain, Africa, and the Atlantic, pg 44-46, 50-53

Central Africans, Atlantic Creoles, and the Foundation of the Americas, 1585-1660, Linda M. Heywood, John K. Thornton, pg 69-70, 73-78 . Slavery and its Transformation in the Kingdom of Kongo by Linda M. Heywood pg 4-7, 12-15

Slavery in Africa: Historical and Anthropological Perspectives, by Suzanne Miers and Igor Kopytoff (eds.), pg 9-13, 56

Slavery and Slaving in African History by Sean Stilwell, pg 5-11. Slavery in Africa: Historical and Anthropological Perspectives by Suzanne Miers and Igor Kopytoff (eds.), pg 7-11, 17

Legal Encounters on the Medieval Globe by Elizabeth Lambourn (ed), pg 86-108

A Social History of Ethiopia: The Northern and Central Highlands from Early Medieval Times to the Rise of Emperor Téwodros II by Richard Pankhurst pg 66

An Introduction to the Economic History of Ethiopia by Richard Pankhurst, pg 377-380. Encyclopaedia Aethiopica Vol 4, edited by Siegbert Uhlig, pg 678

Slaves and Slavery in Africa Volume 1, by John Ralph Willis (ed), pg 125-137

Mamluk Cairo, a Crossroads for Embassies: Studies on Diplomacy and Diplomatics edited by Frédéric Bauden, Malika Dekkiche pg 674-678

Slaves and Slavery in Africa Volume 1 edited by John Ralph Willis pg 125-137, Slaves and Slavery in Africa: Volume Two: The Servile Estate By John Ralph Willis pg 146-149

Du lac Tchad à la Mecque: Le sultanat du Borno et son monde (xvie - xviie siècle) by Rémi Dewière pg 194, 322

Du lac Tchad à la Mecque: Le sultanat du Borno et son monde (xvie - xviie siècle) by Rémi Dewière pg 207, 183, The Slave and the Scholar: Representing Africa in the World from Early Modern Tripoli to Borno (N. Nigeria) by Rémi Dewière

A Seventeenth-Century Belgian Visitor to Agadez and the North of Nigeria by Joseph Kenny, Du lac Tchad à la Mecque: Le sultanat du Borno et son monde (xvie - xviie siècle) by Rémi Dewière pg 190

Slavery in Africa: Historical and Anthropological Perspectives, by Suzanne Miers and Igor Kopytoff (eds.), pg 66-69. Transformations in Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa By Paul E. Lovejoy

Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, by John Thornton, 1400–1800, pg 103-105

Slavery in Africa: Historical and Anthropological Perspectives, by Suzanne Miers and Igor Kopytoff (eds.), pg 61-66

Paths in the Rainforests: Toward a History of Political Tradition in Equatorial Africa, by Jan Vansina, pg 146-162, Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, by John Thornton, 1400–1800, pg 79-80

T. C. McCaskie, State and Society in Pre-colonial Asante, pg 37-39

Warriors, Merchants and Slaves: The State and the Economy in the Middle Niger Valley, by Richard Roberts, 1700–1914

Wives of the Leopard: Gender, Politics, and Culture in the Kingdom of Dahomey By Edna Bay pg 12-13, 22-23, 318-320

A History of West Central Africa to 1850, by John K. Thornton, pg 6-9.

Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800, by John Thornton, pg 83-84, 91-93

Slavery on the Frontiers of Islam by Paul E. Lovejoy pg 87-107

How Societies Are Born: Governance in West Central Africa before 1600, by Jan Vansina, pg 174-177

Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800, By J. Thornton, pg 98-99, How Societies Are Born: Governance in West Central Africa before 1600, by Jan Vansina, pg 177-178.

Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800, by John Thornton, pg 100-101, 107, pg 137

Africa’s Development in Historical Perspective, by Emmanuel Akyeampong, Nathan Nunn (eds), pg 450-456.

The Kongo Kingdom: The Origins, Dynamics and Cosmopolitan Culture of an African Polity, by Koen Bostoen, Inge Brinkman (eds), pg 103-122, A History of West Central Africa to 1850, by John K. Thornton, pg 74-82, 103-106, 128-136

The Atlantic Slave Trade from West Central Africa, 1780–1867, by Daniel B. Domingues da Silva, pg 73-88, The Kongolese Saint Anthony: Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian Movement, by John K. Thornton, 1684-1706, pg 203- 214.

The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 3, AD 1420-AD 1804 edited by David Eltis et al., pg 124

“I remember that when i was a little boy, i heard that the English came to the coast of Africa with their ships, for cargoes of slaves, for the pupose of taking them to their own country and eating them.” Asante King Kwaku Dua in 1848.

This topic has unfortunately not been examined in detail, but numerous references can be found from as early as 1455 from the Senegambia, the Gold Coast, Cameroon, and Angola. see: Africa’s Discovery of Europe: 1450-1850 by David Northrup, pg 166. The Rise of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade in Western Africa, 1300–1589 By Toby Green pg 87, n. 78.

First Footsteps in East Africa, Or, An Exploration of Harar, Volume 1 By Sir Richard Francis Burton, pg 49

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by Elizabeth A. Eldredge, pg 62, 81

The Kongolese Saint Anthony by John Thornton, pg 203-205

Collected works of Nana Asma’u, daughter of Usman ‘dan Fodiyo (1793-1864), pg 191 by Jean Boyd, Beverly Mack (eds),

The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 3, AD 1420-AD 1804 edited by David Eltis, pg 97-101,

Paul E. Lovejoy, Transformations in Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa pg 81-87

Joseph C. Miller, The Significance of Drought, Disease, and Famine in the Agriculturally Marginal Zones of West-Central Africa, pg 17–61

Abolitionism and Imperialism in Britain, Africa, and the Atlantic, by Derek R. Peterson, pg 4-18

West African Slavery and Atlantic Commerce: The Senegal River Valley, by James F. Searing, 1700–1860

Commercial Transitions and Abolition in West Africa 1630–1860, by Angus E. Dalrymple-Smith, pg 155-161

From slave trade to legitimate commerce by Robin Law (ed.), pg 20-21

The End of Slavery in Africa, by Suzanne Miers, Richard Roberts (eds.), pg 27-38, Slavery and Slaving in African History, by Sean Stilwell, pg 23-24, 72-85

Slavery in Africa: Historical and Anthropological Perspectives by Suzanne Miers and Igor Kopytoff (eds.), pg 26-35

The End of Slavery in Africa, by Suzanne Miers, Richard Roberts (eds.), pg 7-20

Slavery in Africa: Historical and Anthropological Perspectives by Suzanne Miers and Igor Kopytoff (eds.), pg 73-74, The End of Slavery in Africa, by Suzanne Miers, Richard Roberts (eds.), pg 22-25

Commercial Agriculture, the Slave Trade and Slavery in Atlantic Africa, by Robin Law, Suzanne Schwarz, Silke Strickrodt (eds), pg 258-264

The Aftermath of Slavery: Transitions and Transformations in Southeastern Nigeria by Chima Jacob Korieh, Femi James Kolapo, pg 63-71

Slavery in Africa: Historical and Anthropological Perspectives by Suzanne Miers and Igor Kopytoff (eds.), pg 75-77

Somono Bala of the Upper Niger: River people, Charismatic Bards, and Mischievous Music in a West African Culture by Daniel Harrington. Warriors, Merchants, and Slaves: The State and the Economy in the Middle Niger Valley, 1700-1914 by Richard L. Roberts,

La fabrication du Patrimoine : l’exemple de Gorée (Sénégal) by Hamady Bocoum and Bernard Toulier, Shadows of the Slave Past: Memory, Heritage, and Slavery by Ana Lucia Araujo, pg 58-66.

This was a really good and thorough article, thank you for writing it

Minor nit-pick, would you mind tweaking the sentence on "the capture of the Sultan’s nephew, Alī b. ‘Umar [Medicon], who was ultimately sold in Tripoli.." to maybe something like "the capture of [Medicon], the nephew of Sultan Alī b. ‘Umar, who was ultimately sold in Tripoli", since it is phrased in a way that people could think Alī b. ‘Umar was the same person as Medicon who was ultimately sold in Tripoli?