Texts from the Periphery: Manuscript cultures in West Africa's frontier regions.

At the turn of the 20th century, one of the most remarkable contributions to African ethnography was produced by Umaru al-Kanawi, a Hausa scholar born in Kano (Nigeria), who, after a brief stay in Salaga (Ghana), settled in Kete-Krachi (*Ghana) in 1896 and composed his influential work.

In his discussion of pre-colonial commerce, Umaru observes: “In Hausaland, the most important long-distance trade is to Gonja (northern Ghana). Many traders go to Gonja in caravans of one hundred or more people; they travel with women and children, and there are leaders and guides.”1

Umaru’s family was part of a widely dispersed diaspora of merchant-scholars who had, since the late Middle Ages, established themselves across a dense network of market towns in the Upper Volta region of northern Ghana, the most prominent of which was Salaga. His two brothers had lived in Salaga as traders since the 1870s, and Umaru himself visited them periodically before ultimately relocating to the town in 1891.2

At its peak of prosperity during the early 19th century, Salaga was a cosmopolitan entrepot organized into distinct wards that housed merchant communities arriving with donkey caravans, carrying kola, textiles, and gold from the kingdoms of Asante, Gonja, Mossi, and Hausaland.3

Each ward was governed by its own leader, known as the mai-unguwa (Hausa for ‘the master of the ward’). Some came from Mossi country (in modern Burkina Faso), others were members of Dyula trading networks (from Mali), others belonged to the ‘Beriberi’ communities (from Bornu), a few came from Borgu (Benin/Niger), but the majority were of Hausa origin.4

The external trade of Salaga was controlled by the regional hegemons of Asante and Gonja, the latter of which was a vassal of the former, but always sought to assert its autonomy and seize control of the lucrative trade of Salaga.

In 1876, the ruler of Gonja’s Kpembe province attacked the Asante officials stationed at Salaga. According to the Chronicle of Salaga written around 1892 by Maḥmūd b. ʿAbd Allāh, a native of the town, the merchants of Salaga tried to protect the Asante by offering them sanctuary in the mosques. Ultimately, however, Gonja forces overwhelmed the Asante of Salaga and compelled the townspeople to surrender their property.5

In the aftermath, Salaga entered a period of sharp decline, as both its trade and its merchant communities abandoned it for other regional centers like Kete-Krachi. Umaru al-Kanawi, who had set up a school in Salaga before moving it to Kete, attributed the former’s collapse to the actions of the rulers of Kpembe, remarking that

“The rulers acted so tyrannically in public that they made their village like a cadaver on which they sat like vultures.”6

(left) Long-distance networks between the Upper Volta (inset), Hausaland (East), and the Made region (North). Map by Holger Weiss.

19th-century copy of the prayerbook ‘Dalāʾil al-Khayrāt’, written in northern Ghana. Ms. Or 6575, British Library.

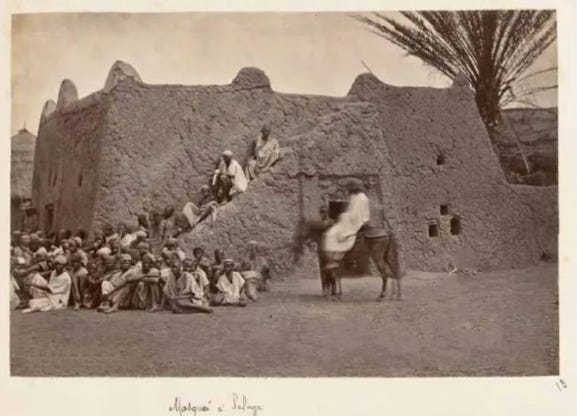

A Hausa-style mosque at Salaga, Ghana. ca. 1886. Image by Édouard Foáà.

Trans-continental trade and travel in pre-colonial West Africa operated through a series of stages, each corresponding to distinct ecological zones dominated by different commercial diasporas such as the Hausa and the Wangara/Dyula.

Within these internal diasporas, communities cultivated identities that transcended political boundaries, relying on a unifying ideology that was essential to business operations and the guarantee of credit. Commerce, religion, and scholarship became a means for many to overcome ethnic and social boundaries, as new identities were created in merchant colonies such as Begho, Bonduku, Buipe, and Salaga.7

Although modern scholarship on West Africa’s “internal diasporas” has been extensive, it has tended to emphasize their commercial activities, while devoting comparatively little attention to their intellectual contributions. This is especially the case for regions such as the Upper Volta, which were long considered peripheral to the better-known historic centers of learning, like Timbuktu, Kano, and Ngazargamu.

Bonduku, Côte D’ivoire. Image by R.A. Freeman, ca. 1889.

While figures such as Umaru al-Kanawi were merchants with far-reaching trading interests, they were also distinguished scholars in their own right.

Umaru’s literary legacy is substantial, comprising more than 130 works, at least forty of which are still extant. Maḥmūd, on the other hand, was the chronicler of Salaga in his capacity as one of its ward chiefs (lampurwura). He led a section of merchant-scholars, mostly of Hausa origin, who were expelled from the town after a civil war in 1892.8 He is also known as the copyist of the Kitāb Ghanja, an 18th-century chronicle on the history of Gonja, which likely influenced his writing of the Chronicle of Salaga.9

The Kitāb Ghanja tells of the friendship between the kingdom’s founder, Nāba‘a (d. 1583), a Mande ‘prince’ from Mālī, and the Dyula scholar Mahama Labayiru, as well as the conquests of Gonja’s kings until the mid-18th century. Labayiru’s descendants, known by the Mande patronymic Kamaghte, served the Gonja kings as religious authorities. Among these was Umar Kunadi, who completed the Kitāb Ghanja in 1762, and copies of it were circulated widely throughout the region.10

Maḥmūd’s Chronicle of Salaga was itself translated (or possibly co-authored) into Hausa by Malam al-Hassan, a Salaga native originally from Djougou (Bénin), who, in the 1890s, compiled the histories of the kingdoms of Mamprusi, Mossi, Dagomba, and Grunshi (all found in northern Ghana/southern Burkina Faso).11

This literary output by Hausa and Dyula scholars in the Upper Volta exemplifies the shared intellectual tradition of West Africa’s manuscript cultures, which has only recently begun to be fully recognized in modern studies of Africa’s intellectual history.

The Kano chronicle, for example, records that during the reign of King Yakubu (r. 1452-1463) “the Fulani came to Hausa land from Mali bringing with them books on divinity and etymology,” they then “went to Bornu leaving a few men in Hausaland.”12

The Fulbé (Fulani) constituted another significant scholarly diaspora in the region, especially the Toroɓɓe/Torodbe clerisy, which included some of the most prominent scholars in the kingdoms of Bornu and Bagirmi (modern Chad). While many of these scholars settled in major urban centers such as Kano, others established themselves in rural communities along the frontier.

Among these was the theologian Muḥammad al-Wālī (fl. 1688), a rationalist whose writings combined classical philosophy and local oral traditions to challenge the ‘blind acceptance’ of religious authority:

“The imitator is he who accepts the words of the ʿulamāʾ (scholars) without proof and then falls back to blind acceptance.”

Despite residing in a small hamlet in the kingdom of Bagirmi, his works circulated widely and have been discovered in manuscript collections across Mali, Nigeria, Egypt, and Algeria.

The philosophical theology of Muḥammad al-Wālī is the subject of my latest Patreon article. Please subscribe to read more about it here, and support this newsletter:

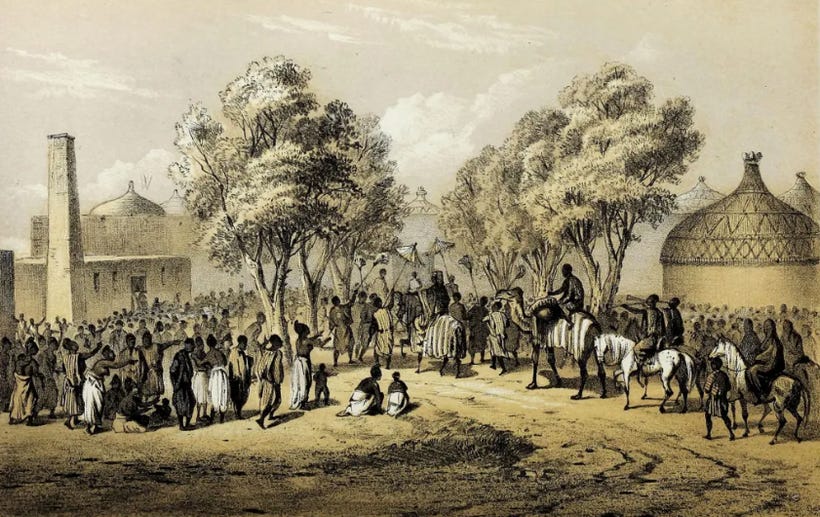

Más-eñá, Return of the Sultan from the Expedition, 4 July 1852. By H. Barth.

Nineteenth Century Hausaland: Being a Description by Imam Imoru of the Land, Economy and Society of His People. by Douglas Edwin Ferguson, pg 376

Arabic Literature of Africa: The writings of western Sudanic Africa by John O. Hunwick, Rex S. O’Fahey, pg 586-587

Polanyi’s “Ports of Trade”: Salaga and Kano in the Nineteenth Century by Paul E. Lovejoy

Salaga: A Nineteenth Century Trading Town in Ghana by N. Levtzion, in ‘Asian and African Studies: Vol. 2’, pg 217-219

Salaga: A Nineteenth Century Trading Town in Ghana by N. Levtzion, in ‘Asian and African Studies: Vol. 2’, pg 223-226

Nineteenth Century Hausaland: Being a Description by Imam Imoru of the Land, Economy and Society of His People. by Douglas Edwin Ferguson, pg 15-16

Caravans of Kola: The Hausa Kola Trade, 1700-1900 by Paul E. Lovejoy, pg 29-35, Muslims, the State, and Society in Ghana from the Precolonial to the Postcolonial Era. Holger Weiss pg 59-61

Nineteenth Century Hausaland: Being a Description by Imam Imoru of the Land, Economy and Society of His People. by Douglas Edwin Ferguson, pg 239, n. 130

Arabic Literature of Africa: The writings of western Sudanic Africa by John O. Hunwick, Rex S. O’Fahey, pg 545

The Ethnography of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast by J. Goody pg 36-37, Between Accommodation and Revivalism by Holger Weiss pg 70-71, Imams of Gonja The Kamaghate and the Transmission of Islam to the Volta Basin by Andreas Walter Massing pg 60-62, Arabic Literature of Africa: The writings of western Sudanic Africa by John O. Hunwick, Rex S. O’Fahey, pg 542-543.

Arabic Literature of Africa: The writings of western Sudanic Africa by John O. Hunwick, Rex S. O’Fahey, pg 584-586, The growth of islamic learning in ghana. Ivor Wilks.

The Kano Chronicle by R. Palmer, in ‘The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Volume 38’, pg 76-77