The African origins of Cola: Long distance Trade in pre-colonial West Africa (ca. 1000-1900 CE)

In classical and medieval Arabic sources, West African trade is most commonly associated with gold, which was exchanged along trans-Saharan routes that crisscrossed the desert in patterns later echoed by colonial “mine-to-coast” railways.

Despite the disproportionate emphasis on gold in external sources, internal accounts indicate that West Africa’s economy was primarily based on local and regional exchanges, sustained by a vast, interlocking network of routes linking cities and markets across diverse ecological zones. These routes were the culmination of many centuries of commercial evolution, onto which the trans-Saharan routes were later grafted.

Although many products were traded along these old trade routes, kola was frequently identified as the most significant commodity of intra-African exchange in the region.

The importance of kola in West African societies cannot be overstated. It was associated with religious rites and initiation ceremonies; it functioned as a stimulant and medicinal substance, as a symbol of hospitality, and in diplomatic relations between rulers.

Kola captured the imagination of European consumers in the second half of the 19th century, first as a drug and then as a tonic that was used as an ingredient in a wide range of emerging cola beverages.

This article outlines the history of the Kola trade in pre-colonial West Africa and the Atlantic world.

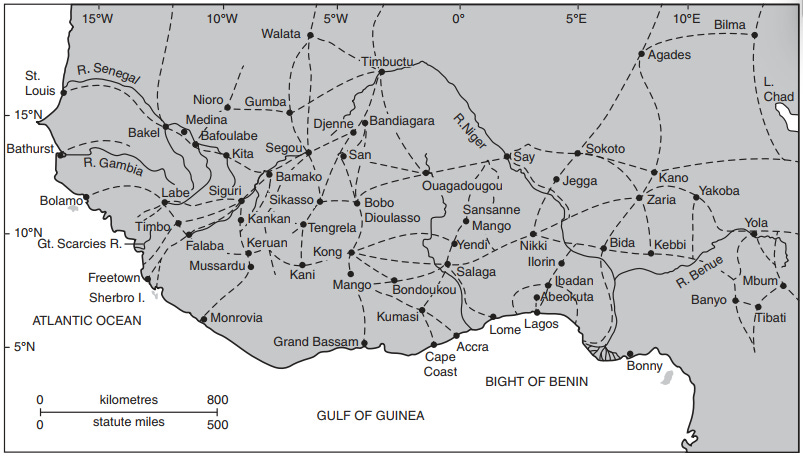

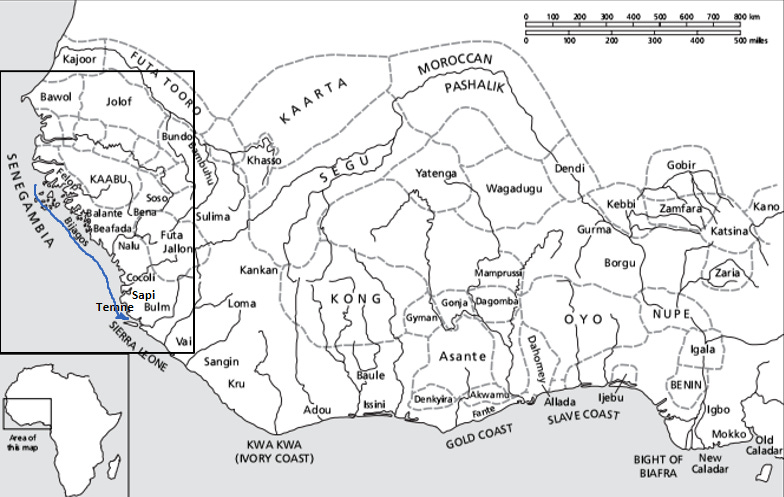

Long-distance trade routes in West Africa during the 19th century. Map by A. Hopkins.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by joining our Patreon community. Subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Historical accounts:

Much of what is known about Kola production and trade comes from internal West African accounts and some European sources concerning the coastal regions. Unlike most African luxuries, which are well documented in classical and medieval Arab accounts, Kola only appears once in a 14th-century description of medieval Mali by al-Umari.1

There are numerous references to Kola in the Timbuktu chronicles, especially in the Tarikh ibn al-Mukhtar (written in 1664), which connects it to the wealth of medieval Mali:

“Its people were endowed with wealth and a life of comfort. It should be enough for you to mention the gold mines, and the kola nut tree, the like of which is not found in all the lands of Takrur, except in Borgu.”2

Kola, which is rendered as ‘kūru’ in this text, is known as Guru, Guro, Goro in several West African languages of the Savanah region (Songhay, Fulfulde, Malinke, Hausa, Kanuri). The region of Borgu that is mentioned in this text was located along the northern borderlands of Nigeria/Benin and wasn’t a Kola-producing area, but was instead a major settlement of Wangara traders who dealt in Kola obtained from the Volta basin in modern Ghana.3

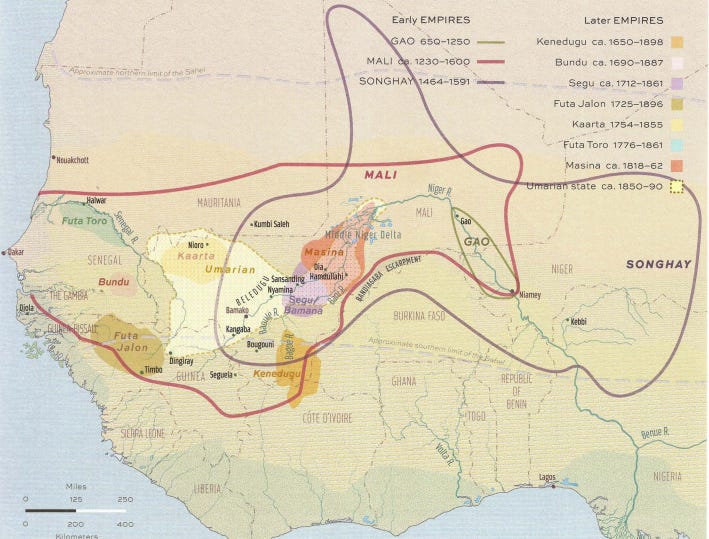

Empires of West Africa. Map by A. LaGamma

Linguistic evidence indicates that the term for Kola in the languages of the Savanah region was borrowed from the West-Atlantic languages of the Sierra Leone-Guinea border area. There is a considerable diversity in words for kola nuts in the West-Atlantic languages of the forest zone (from Guinea to Nigeria), although few areas traded north sufficiently early to influence the vocabulary of the savanna peoples. Among these were the Temne, a West Atlantic speaking group who moved to Sierra Leone by the 14th century, and used the term kͻla, which is found in related languages of the Mel-subgroup.4

This West African term was later adopted by European traders during the 15th/16th century, beginning with the Portuguese (‘Cola’), who were later followed by the English (‘kola’), and the French (‘kola’).5

Excavations at the site of Togou in Mali recovered the remains of Kola seeds (C. nitida ) and Safou fruit (D. Edulis) in a settlement that contained rectilinear mud-brick architecture dated to the 11th century. Archaeologists suggest that this kola arrived at the site by river or overland from the Sierra-Leone/Guinea region. The finds indicate that internal trade in medieval West Africa was fairly ancient, and was, in part, facilitated by ecological differences between the Savanah and Forest zones, rather than simply being a consequence of external demand for gold.6

The Tarikh al-Sudan (written in 1655) mentions that the Songhai emperor Aksiya Muhammad Bonkana was “inordinately fond” of the taste of Kola.7 The Tarikh Ibn al-Mukhtar lists Kola among the gifts and payments given to the qadi of the Sankore madrassa of Timbuktu for its reconstruction in 1581-2, after receiving a large sum of gold (223 grams) as payment. Kola nuts were among the gifts and payments given by the Aksiya Dawud (r. 1549-1582) to his fanfas (leader of his royal estates), and political gifts exchanged between the Songhay elites and the Moroccan armas after the fall of the empire.8

The Chronicle of Kano (Nigeria), which was written in the 19th century but based on earlier oral sources, mentions that the trade route linking the Hausalands (northern Nigeria) and Gonja (northern Ghana) was opened during the reign of King of Kano, Dauda (c. 1421-c. 1438). Other material in the same chronicle supports the 15th-century date, although kola is not specifically mentioned. Hence, King Abdullahi Burja (c. 1438-c. 1452) ‘opened the roads from Bornu to Gwanja [Gonja],’ and during the time of Yakubu (c. 1452-c. 1463) ‘merchants from Gwanja began coming to Katsina.’9

The Wangarawa Chronicle, written 1650-51, suggests that direct trade with the Akan forests may have existed by the end of the 15th century, with Borgu and Gonja included on the list of original Wangara settlements. These accounts, including the aforementioned reference to Borgu in the 17th-century Tarikh Ibn al-Mukhtar, suggest that the eastern wing of the Kola trade predated its better documented expansion of the 19th century.10

Earlier accounts written by the Portuguese in the 16th and 17th centuries indicate that Kola production and trade were of considerable antiquity along the coast of Upper Guinea (Senegal, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea-Conakry, Sierra Leone, and Liberia)

The 16th-century accounts of André Alvares de Almada and André Donelha emphasize the extraordinarily high value of kola there, which could be used to purchase virtually any item. Donelha also offers a detailed description of the kola trade, observing that its value was higher upriver in the Gambia than near the coast at Guinea-Bissau. In the Gambia, 40 kola nuts were the equivalent of a Portuguese gold cruzado, and the nuts could be exchanged for textiles (panos) and other goods.11

An early 17th-century account by the Portuguese chronicler Manuel Álvares describes trade in the Sene-Gambia, involving gold and cola, which Mande-speaking traders carried out within West Africa and as far as the Maghreb and Mecca:

“Some gold is traded, which comes from the hinterland at the direction of the Mande merchants who make their way to the coast from the provinces and lands of their supreme emperor Mande Mansa. These commodities are obtained from the country in exchange for illegal cloth, different sorts of precious stones from the East Indies, beads, wine and cola – the last so much valued that throughout Ethiopia [ie; West Africa] it is reckoned a gift from heaven, and Mande merchants carry it to all parts of Barbary and, in powdered form, as far as Mecca.”12

By the 18th and 19th centuries, kola was a common luxury among the aristocracies of the Hausa states and Bornu and was even imported as far north as Fezzan.13

The German traveller Heinrich Barth, who visited the ‘Central Soudan’ (Chad, and Niger, northern Nigeria) between 1849 and 1855, reported that large sums are expended by West Africans upon this luxury:

“The gúro, or kóla nut, which constitutes one of the greatest luxuries of Negroland, is also a most important article of trade. Possessing this, the natives do not feel the want of coffee.”14

In the Muslim West African societies where intoxicating substances were restricted, and alternatives like hashish and opium were unknown, Kola and Tobacco were the only substances that were in use as stimulants. As Gustav Nachtigal noted while visiting the same region in 1874: “For the Hausa and the people of Bornu the guro [kola nut] has become a luxury even more indispensable than is coffee or tea for other people.”15

His counterpart, Paul W. Staudinger, who visited the same region in 1885, remarked that “the arrival of a new consignment of kola nuts is as great an event for the Hausa as is the first appearance of a seasonal dish for a gourmet in Europe.”16

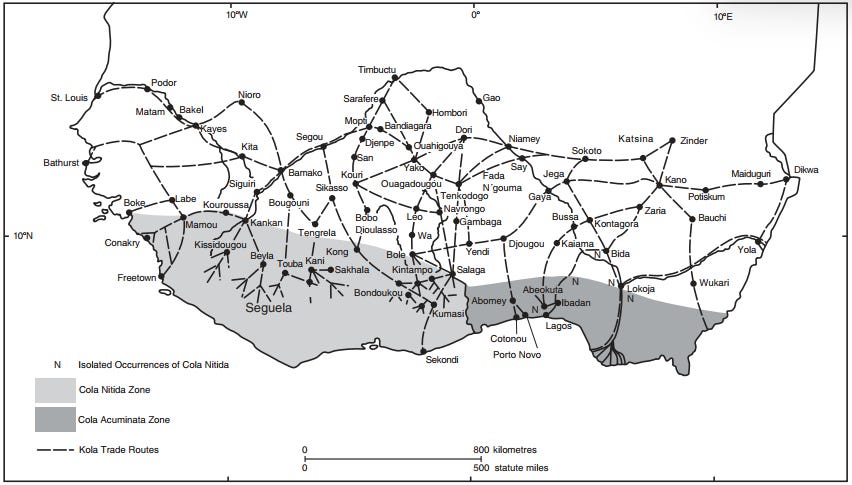

Distribution of Kola and Trade Routes in West Africa. Map by A. Hopkins

Production

The most common species of kola nuts in West Africa are Cola nitida and Cola acuminata, which are the most economically important of the more than 125 Cola species native to the West African forest zone. Of these, C. nitida was virtually the only kola exported from the producing areas in the forests of West Africa to markets in the Savanna to the north. C. acuminata was eaten as well, but almost entirely within the region where it was cultivated. 17 (see map above)

In some regions, Kola trees were deliberately cultivated like other domesticated crops of Africa. The Dan, a Mande-speaking group in the Nimba region of northern Liberia, practiced two methods of planting kola. The first was to move volunteer scions from beneath parent trees and to transplant them nearby. The second was by planting nuts, which were soaked in water for several days before sowing to promote germination.18

The fruit of the kola grows in pods that contain from three to twelve nuts. The trees bear fruit within six to seven years after planting and continue to produce for several decades. Harvests are seasonal, with most of the crop picked between October and February. The fruit grows in pods that contain from three to twelve nuts. Yields per tree vary, but a single tree can produce over a thousand nuts per year.19

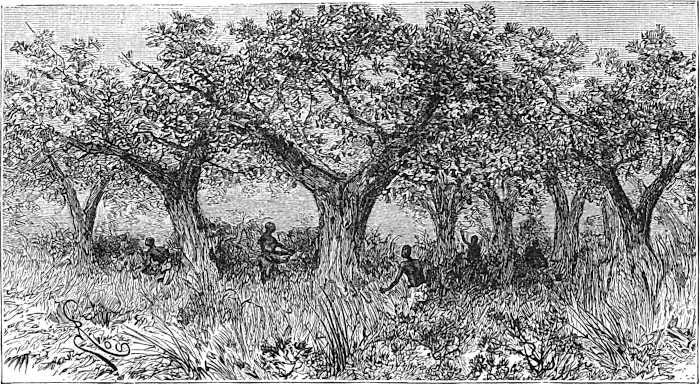

‘A kola plantation’ illustration by L. Binger, 1892. The accompanying text suggests this plantation was located somewhere near the city of Kong in northern Côte d’Ivoire.

Kola Nuts. Shutterstock Image

In the Upper Guinea region, the Baga, Temne, and Bullom/Bulm (see map below) were the groups at the producing end, especially the first two on the northern coast of Sierra Leone. There was no evidence of a large-scale plantation culture in this region, yet the crop was always huge. Portuguese traders, at times, complained of declining yields and made a failed attempt at cultivating Kola in the Geba-Gambia area during the 16th century.20

These trees, along with local pepper (known as malaguetta) and sea salt, induced Mande-speaking traders to venture hundreds of kilometers through rain forest to settle among West Atlantic-speaking groups living in the Cape Mount area, beginning sometime during the c. 1100-c. 1500.21

In the Asante region of modern Ghana, the gathering and processing of the nuts was mostly done on a small scale by family labour, including slaves and pawns, on lineage land. At harvest, the pods are soaked in water for several hours to weaken the shells. The nuts are then removed, dried, and stored in bundles lined with banana or cocoa-yam leaves. Storage is important, since aged nuts command a higher price. If the kola was not sold to a middleman, the head of the family transported it to the markets for sale.22

Operation of trade:

The trade in Kola represented an important exchange between the varied ecological zones of the Forest, Savanna, Sahel, and Atlantic coast, and demonstrates the level of interdependence between widely separated areas of pre-colonial West Africa.

Despite their popularity as a trade item, kola nuts are difficult to transport, must be kept moist, and are susceptible to pests. They must be frequently unpacked, checked, watered, and repacked. Kola trading was thus a high-risk venture that produced considerable profits for those engaged in the trade. They were wrapped in bundles containing 100 nuts, a common wholesale measure, or 2,000 nuts, the amount of a head-load and one-half of a donkey load.23

Map showing the Upper Guinea region. The blue outline marks the extent of the Biafada-Sapi network (shown as ‘Beafada’ on this map). For overland and riverine networks, see the map in the introduction.

A large number of historical and archaeological writings have focused on the structure of trade in West Africa, emphasizing the establishment of trade diasporas associated with, among other items, the marketing of Kola.

In 15th/16th century Sierra Leone, priestly lineages of the Temne-Sapi known as the Tangomaas, who were in charge of the shrines of the Simo society, also controlled the region’s Kola trade. Some of the lançados (Luso-Africans) who obtained kola from the Tangomaas became fully integrated into the communities of the latter, adopting local customs (circumcision, scarification, amulets, dressing), and a new identity as ‘Tangomaos’, who appear in contemporary Portuguese accounts. This integration was for reasons of mutual advantage, including the shared use of large sail-boats that could transport more cargoes of kola, iron, and other items.24

The coastal and riverine kola trade between Guinea-Bissau and northern Sierra Leone was dominated by Biafada mariners (Sapi-speakers belonging to the Mel subgroup of the West Atlantic languages). Since the late Middle Ages, Biafada mariners ventured southwards from the vicinity of the capital of Guinea-Bissau to the area just north of Freetown in Sierra Leone, using large canoes to obtain kola, pepper, and other commodities from Baga, Temne, and Bullom. This trade expanded during the 15th-16th century, and the Sapi language was disseminated early on as a commercial lingua franca, as a consequence of these activities.25

‘Native boats’ Guinea-Conakry.

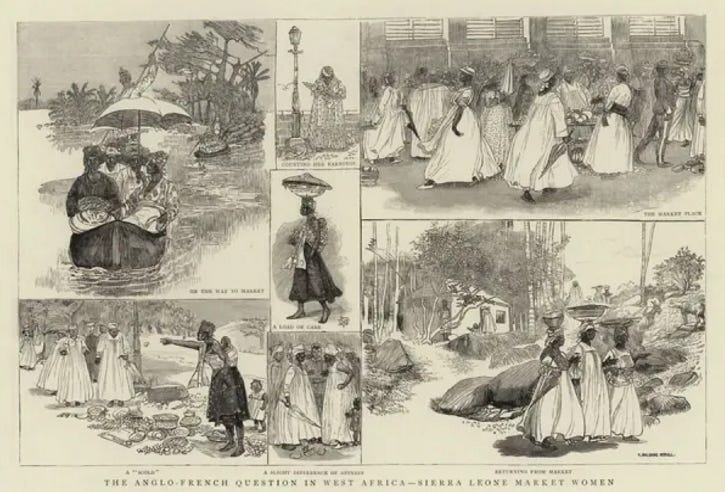

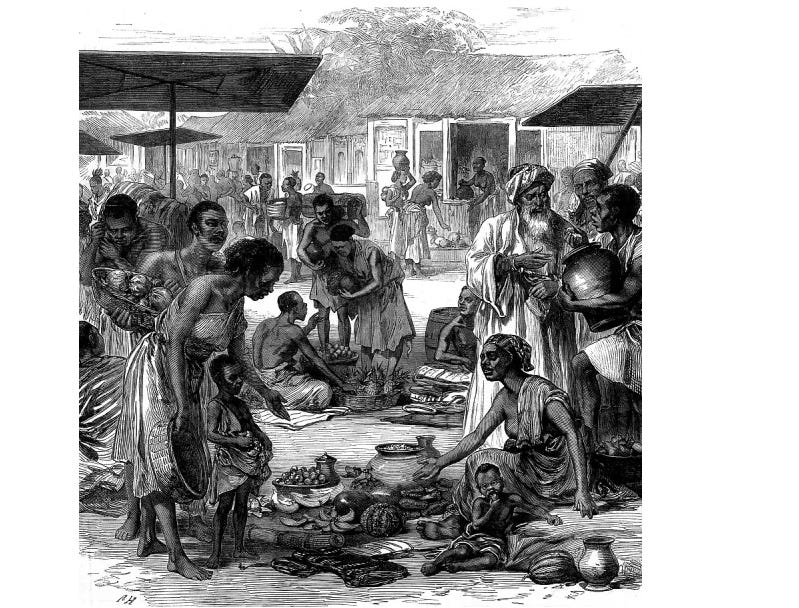

Sierra Leone Market Women. Illustration for The Graphic, 13 December 1890.

From the north of Guinea-Bissau to the Senegambia, several commercial diasporas, most prominent of whom were the Niominka, carried on an extensive coastwise and riverine commerce that extended from Cape Verde to the Gambia River. They connected with those of Banyun, who expedited the overland passage of pepper and kola in the interior from the Cacheu River (in northern Guinea-Bissau). They innovated the construction of larger watercraft with sails, which revolutionized patterns of coastwise and riverine trade and greatly increased the quantities of bulk commodities such as kola and iron bars transported between markets.26

By the mid-17th century, the coastal trade amounted to at least 225 metric tons per year, a figure calculated from the estimated 10000 loads of kola of 3000 nuts per load, which contemporary accounts record. This trade was probably much smaller than the one carried out in the interior.27

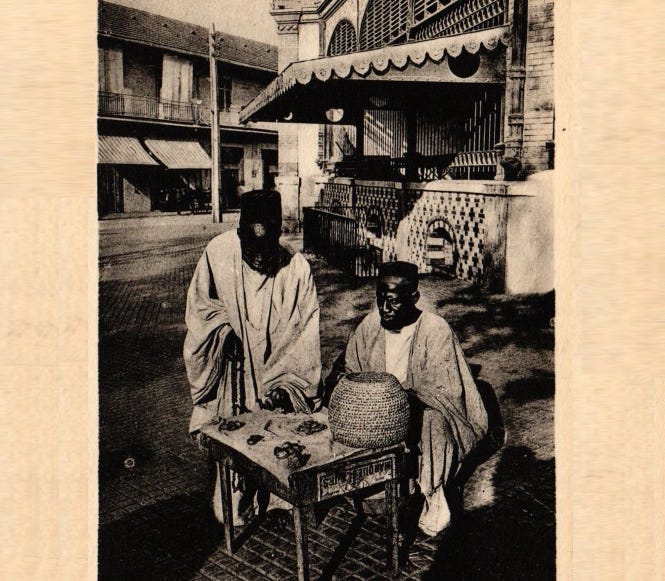

Kola traders in Dakar, Senegal. early 20th century.

‘Vue de Rufisco’ [View of Rufisque], Senegal, By J. Barbot. This engraving, made shortly after he visited the region in 1681, depicts various types of local watercraft.

Sailboat near Goree, Senegal. 19th-century engraving.

The Habour of Rufisque, Senegal. ca. 1906. Edmond Fortier.

Loading the boats at Rufisque, Senegal.

In the interior, the Banyun traders mentioned above prospered by exchanging commodities obtained from Mande trade networks overland with Biafada-Sapi mariners of the forest zone.

They carried out a mostly overland trade using a combined riverine and portage network since the Guinea current prevented northward sailing. Their links with Mande traders in the inland towns between Gambia and northern Sierra Leone, since the late 16th century, meant that a considerable portion of the kola carried across the Sahara passed along their trade routes.28

Mande traders visiting the town of Farim (northern Guinea-Bissau), purchased huge quantities of kola. In contrast to the 7 or more vessels dispatched to the coast in 1608, the Portuguese trader Francisco de Lemos Coelho reported that during the 1640s and 1650s, as many as 18 river-craft transported kola to Farim and beyond to Kabu. The vessels carried 4-5000 barrels, each containing some 3,300 kola. Coelho characterized the traders at Farim as Muslim Soninke (ie; Jakhanke), adding that they had converted all Mandinka to Islam. By the 18th century, this overland trade supplanted the coastward trade.29

In the western half of the trade, many of the old merchant communities associated with medieval Mali, who are known as the Soninke/Jakhankhe/Dyula/Wangarawa, trace their origins back to the early 2nd millennium BC, when the first references to kola appear.

Map of West Africa showing the dispersion routes taken by the Jakhanke (yellow), Juula (green), and Wangarawa (red)

The nucleus of these Mande trading communities was located between the cities of Dia and Djenne in Mali, from which they spread westwards to the Senegambia, where they were known as the Jakhanke; southwards to Ghana, where they were known as the Dyula/Juula; and eastwards to Hausaland, where they were known as the Wangarawa.

These were later joined by other Mande-speaking groups such as the Marka of the Segu empire (in Mali) and the Kooroko merchants of the Wasulu empire of Samori Ture (in Guinea-Conakry). Both groups were involved in the kola trade long before they became the commercial agents of the hegemonic states.30 The Scottish traveller Mungo Park briefly mentions “kolla-nuts” in his 1799 account, describing the gifts used in the marriage customs of the Mandinka of Kamalia (southwest of Bamako, Mali).31

The French traveller René Caillié, who reached Timbuktu from the coast in 1828, makes numerous references to the ‘colat-nuts’ as political gifts and as marriage gifts. He mentions the trade in Kola by merchants in the Mandinka town of ‘Sambatikila’ (Samatiguila in northern Côte d’Ivoire) carried it to Djenne (Mali), and northward to Timbuktu. He adds that “this traffic is not very lucrative, because the journeys are long and troublesome, and they have to purchase food on the road, and to pay for lodgings and transit-duty in all the villages.”32

The caravans in this section were relatively small, consisting of about 75-85 traders with 15 donkeys, each carrying a load of about 3,500 kolas, including the porters. They paid a tax of about 20 kolas at each stop, equivalent to 20 sous (ie; I franc). The caravan he travelled with that year ultimately changed its destination from Djenne to Sansanding after finding out that Kola prices in the former city had fallen by half, apparently due to oversupply, because the city, which had since been conquered by the Massina empire, was at war with Segou. As a consequence of the war, trade moved to ‘Yamina, Sansanding, and Bamako’.33

During the 19th century, the major north-south commercial axis described above, from Djenne to the kola-producing region of the Volta basin, was supplanted by the riverine route that terminated in the Kola-producing region of Wasulu (Guinea-Conakry). According to Binger’s account, this trade was dominated by the ‘Kokoroko’ (ie; Kooroko merchants of Samory’s Wasulu empire in Guinea) and ran northwards into the Marka towns of Mali, and eastwards into the Cote D’ivoire.34

This new route was partially enabled by the expansion of the Somono boatmen, who developed their riverine transportation system into a rapid and cost-efficient means of moving bulky goods over long distances. Its terminus was controlled by the Marka of Segu, in their market towns of Sansanding and Nyamina, which were linked to camel caravans of the Sahel that transported it further north. Unlike the situation on the southern route, this western trade route was considerably profitable, with gross profits of 400% based on exploiting price differentials between cowries, Kola, and salt.35

The empire of Samory (green), and the Tukulor empire (which succeeded Segu)

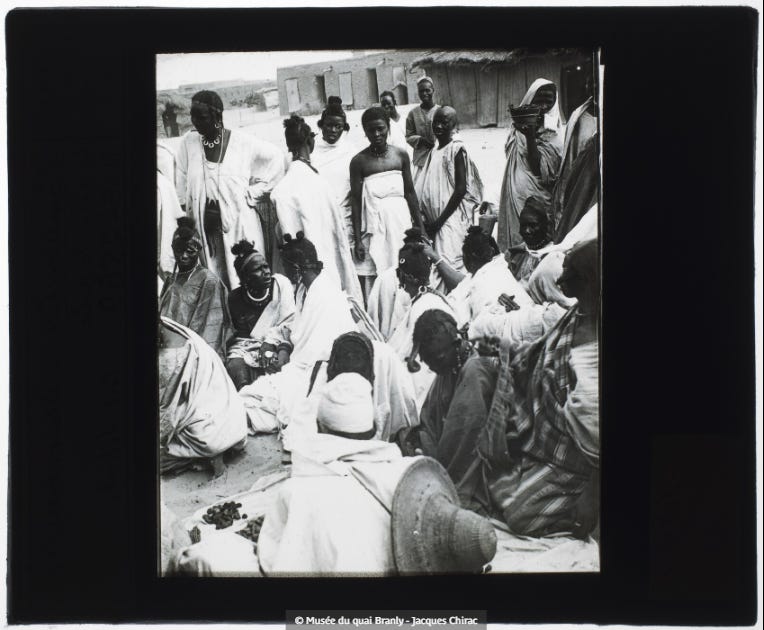

Kola nut sellers in Timbuktu, Mali. ca. 1895. Quai Branly

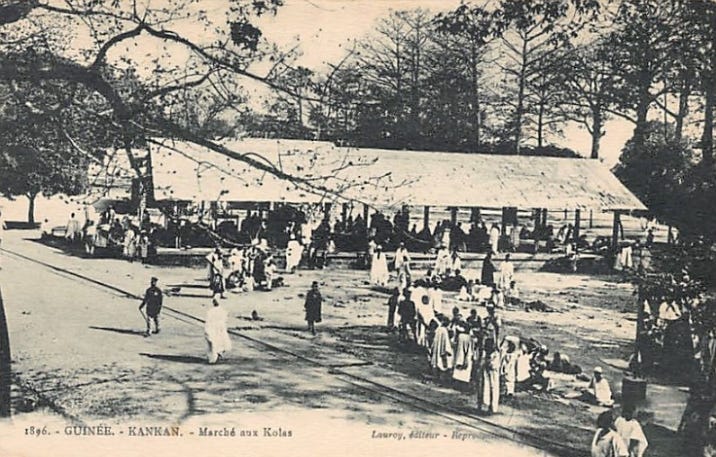

The kola nut market at Kankan, Guinea-Conakry, ca. 1896

painting of ‘Timbuctoo’ in 1852, by Johann Martin Bernatz

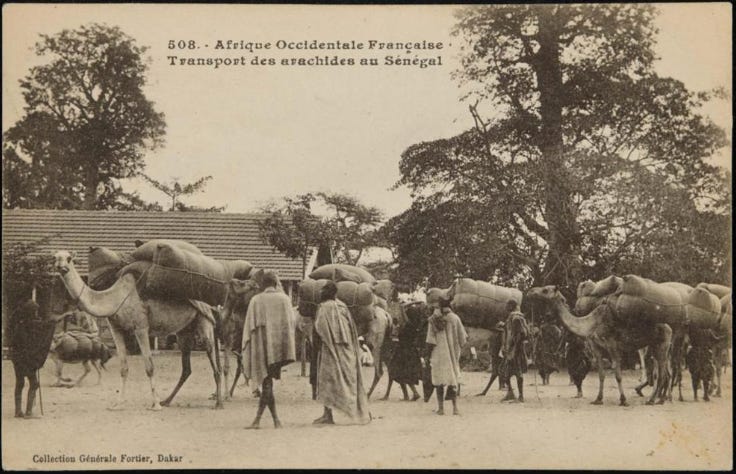

Camel caravan in Senegal. ca. 1906 Edmond Fortier. This specific caravan is transporting peanuts, which are another bulky commodity carried along the same trade routes.

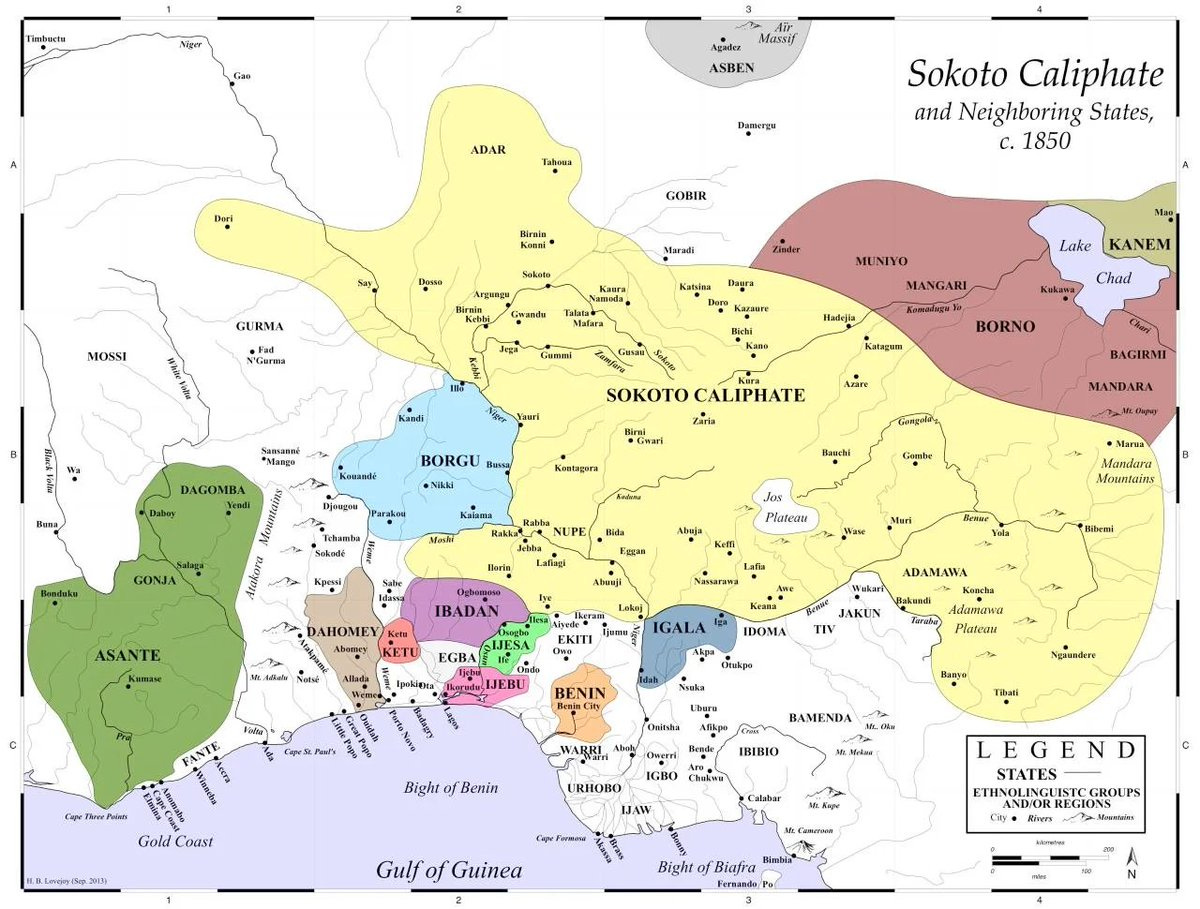

In the eastern half, much of what is known about the Kola trade comes from 19th-century accounts describing trade between the Asante kingdom in Ghana and the Sokoto Caliphate, about 900 km north-east in Hausaland, northern Nigeria.

Map of the Sokoto Caliphate and neighboring states. ca. 1850, by P. Lovejoy.

The chronology for the development of the Hausa trade to the middle Volta basin and the rise of the Asante state coincided. At the time when Hausa settlers established communities in Gonja, Dagbon, and other places in the 18th century, Asante expanded from a small confederation centred around the capital Kumase, conquering most of the kola production zone around 1700, including Gonja, and began to control trade and production of Kola.36

By 1817, when the city of Salaga became ‘the grand emporium of Inta [Gonjal,’ Asante traders were responsible for transporting large amounts of kola to Salaga for sale. The ‘departures of Ashantee caravans’ from Kumase were frequent in the 1817 account of the British envoy Thomas Bowdich. Kola trade was bureaucratized as state agents took over the marketing of the nut up to the time of its sale to a foreign buyer.37

Travellers from Kong and Jenne were not allowed to enter Asante from the north-west but were forced to remain at Salaga for permission to advance southward. At Banda, in 1791, one trader was stopped by an ‘Ashantee chief,’ who told him he would not allow the trader to advance until he had sent to consult the king in Kumasi. The man stayed ten days at Salaga, ‘and, at the expiration of that time, people came from the king of Ashantee, to tell him he might advance.’ He was allowed to continue to the Gold Coast, but only under close supervision.38

Market-place at Coomassie (Kumasi, Ghana). ca. 1873

Asante intervention in kola production and export was in sharp contrast to the relative inability of states to the north and east of the Volta to control the Kola trade. In these regions, and across much of the savanna, the trade was dominated by an established network of commercial diasporas, who acted as a bridge across the social labyrinth of West Africa.

These diasporas had different motives for engaging in long-distance trade; their activities reinforced each other on both economic and religious grounds. In the Volta, the most prominent of these was the Hausa diaspora, which, as mentioned in the introduction, began establishing itself in the region at the end of the Middle Ages.

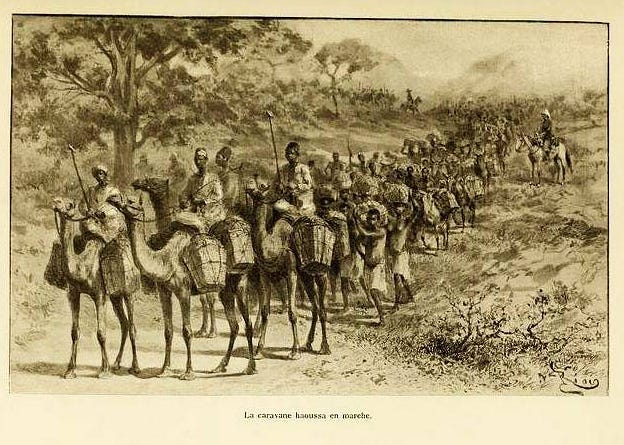

Hausa traders traveled in large caravans, some with as many as 2-5,000 people and an equal number of donkeys and pack oxen that were strung out over several miles. They often had a single leader (madugu) who dealt with local rulers and negotiated road tax (garama). Taxes were usually small; a caravan of about 200 traders and an equal number of donkeys, each carrying a load of kola, paid a toll of about 1.25 loads to a ruler of a major town, and much less in smaller towns.39

Prices fluctuated significantly, but the trade was very profitable, with markups of up to 2-6,000% between the Kola-producing Volta regions and the importing regions of Hausaland and Bornu. The nuts were usually exchanged for dyed cotton textiles, as well as salt and natron, as in the western routes. An estimated 1,500 tons of Kola were imported into the city of Kano during the 1880s, with a trade value of about 38,400,000 German Marks (about $10 million in 1880).40

‘Hausa caravan, in the lead a few camels carrying 4 loads of kola, then women heavily laden with kitchen utensils, behind the porters with a heavy load of kola’ engraving and caption by P L Monteil, 1892. Note that other accounts, especially by René Caillie, mention the participation of women as traders and not merely as companions of their male relatives.

Kano, Nigeria. mid-20th-century photo.

In addition to the Hausa commercial diaspora, several other interconnected trade networks operated in the region between the Niger and Volta basins. The aforementioned Dyula/Dioula/Juula, as well as the Yarse, Borgu-Wangara, and other merchants, formed their own trading diasporas, which overlapped with the Hausa system to form an interlocking grid of commercial networks.

Juula trade routes radiated westwards and northwards from Gonja to the upper reaches of the Niger, ie; to Kong (Cote D’ivoire), Bobo (Burkina Faso), Djenne and other market towns. The Borgu-Wangara (ie; Wangarawa) traders were joined by the Beriberi diaspora from Bornu, along a major pilgrimage route that extended eastwards from Gonja to the Lake Chad basin. Other eastern routes were dominated by Yarse traders of Soninke origin who were linked to the Mossi states (Burkina Faso), from where most donkeys were imported by the caravans.41

The commercial settlements were often separated from indigenous administrative capitals and are thus often referred to as ‘twin towns’. Examples of these include Salaga (town) and Kpembe (capital), Kete (town) and Krachi (capital), and Bonduku (town) and Amenvi (capital). The separation of the traders into their own distinct communities provided some insurance against their potentially disruptive influence and simultaneously permitted greater control over the foreign merchants.

While this separation implies some degree of state control over the caravan trade, the general state policy had to be laissez-faire, and subjects who wanted to participate in the trade did so only by adopting the culture of the different diasporas, or by engaging in petty trade of provisioning the caravans. The traders retained a significant degree of autonomy; if tolls and taxes were excessive, merchants altered their routes, and the exploitive town or state suffered.42

By the end of the 19th century, however, some of the rulers had transferred their capitals to the market towns, most notably at Bonduku and Salaga.

Bonduku, Cote D’ivoire. Image by A. Freeman and L. Binger, ca. 1889.

Samori Ture’s house in Bondoukou.

Uses of Kola:

Kola nuts contain caffeine, theobromine, and kolatin, and like other mild stimulants, including coffee, tea, and cocoa, they can be moderately addictive. The taste for kola is acquired because the nuts are bitter. Both caffeine and theobromine are alkaloids that stimulate the nervous system and the skeletal muscles, while kolatin is a glucoside heart stimulant. Although kola is not taken as a drink but is chewed, it has sometimes been compared with coffee, even being called the ‘coffee of West Africa’.43

The use of kola in Western Africa is wide-ranging and complex. It is employed as a masticatory, a dye, an aphrodisiac, and a critical item in childbirth, weddings, oath-taking, and mediating disputes. It was used in religious practices by diviners, as currency for smaller transactions, paid as tax to rulers, and as medicine for a range of ailments.44

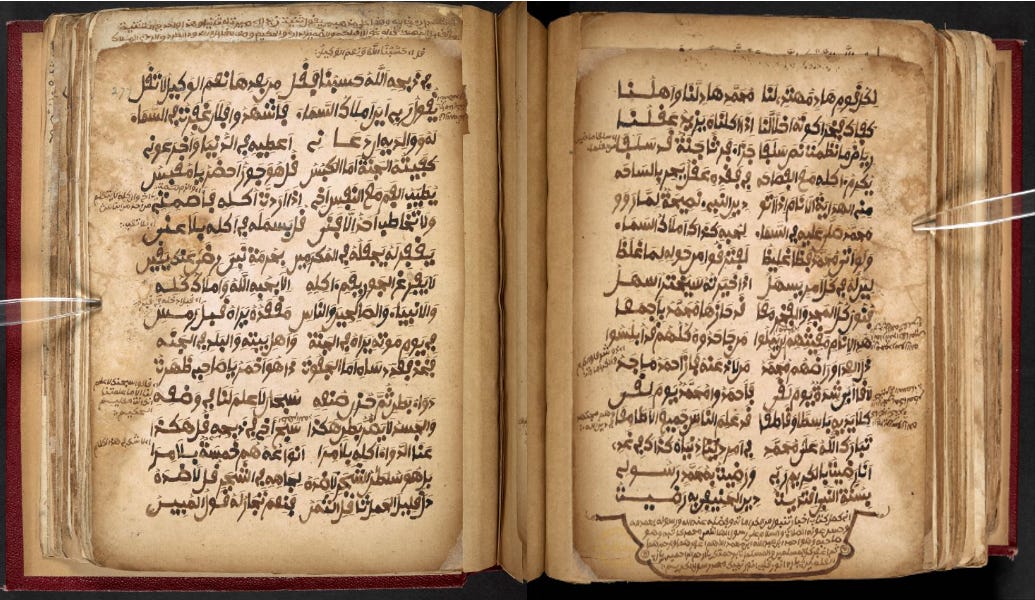

Kola thus appears in several West African medical manuscripts, and depictions of Kola nut and its various containers are well represented across the corpus of West African artwork associated with political authority, trade, and religious rites.

19th century manuscript from northern Nigeria identifying the types of Kola and their medicinal and recreational uses. (Ms. Or. 6880, ff 276v-277v British Library)

Carved wooden containers (orievbee) decorated with brass strips, used for the storage and presentation of kola nuts to guests. 19th-century Benin city, Nigeria.

(left) 16th-century Brass plaque with Warrior and Attendants. Benin City, Nigeria. Met Museum. The small figure on the bottom left is carrying a Kola nut container. (right) Kneeling female figure with bowl (olumeye) for offering Kola. Olowe of Ise, Nigerian, (1875-1938). Dallas Museum of Art.

Kola consumption figured prominently in Bori belief systems of Hausaland, especially in initiation rites. One bori spirit, Cigoro (eater of kola), distributed kola as a mark of possession. The water spirit, Sarkin Rafi or Kogi, provided protection or refuge through kola; it was held that bad influences would pass into the kola. The spirit Bagudu (‘no-running’, i.e., as in battle) recommended kola as a means of syphoning off the urge to flee.45

Above all, kola was consumed in social settings, similar to how people in other societies drink coffee and tea, smoke tobacco, and imbibe alcohol, as explained by Staudinger in 1885:

“The kola nut, goro in Hausa, is offered like a cigar at home and one may be sure it is never refused; on the contrary, it is considered good manners to share it round, even if only in small fragments, before helping oneself. Such nuts, if sent by the king, are a kind of present of honour, and people who have no money to buy them beg them from their friends. Rich people try to make themselves popular and to be regarded as “big men” (babba) by distributing kola nuts, and for the noblemen chewing them is the favourite occupation.”46

In the Kitabul Mas-alati Tanbul, a text by Umaru al-Kanawi from the early 20th century, the Hausa scholar lauds Kola consumption:

“It is brought to us as bundled by its owner,

Presented in the palaces of the Emirs where it is distributed.

Who among the great would not like to eat it?

Which among the rich do not like to taste it with his money?

…It is the food for our great honorable men.”47

Colonial Map of West Africa by Time Maps.

Colonialism and the end of intra-African Trade.

After the colonization of the West African interior in the early 20th century, Imperial conquest broke up the pre-colonial system of exchange towns, roads, and commercial networks. The lucrative long-distance trade in Kola ground to a halt as different colonial governments restricted the movement of goods between their spheres of influence.

In the western half of the region, French boundary policies severely altered regional commercial patterns organized by the Dyula/Juula and other traders, especially between Guinea-Conakry and (British) Sierra Leone. The destruction of the large inland states ended their capacity to finance large caravans and reduced the importance of several towns that had facilitated inter-regional flows. Longer trips, higher risk costs, and imposed duties cut into traders’ profits.

For the first time, trading across interior ecological zones was defined as “smuggling.”

Attempts by the Dyula traders to evade the colonial borders and restrictions came at a high price. When interviewed decades later, elderly Dyula recounted harrowing stories of being chased through “bush paths” by armed patrols, and as proof showed the scars they had sustained from sharp thorn trees and bullets.48

In the eastern half, the donkey caravans that had previously supplied the Hausalands dwindled in size after 1900, and eventually they stopped travelling altogether. Initially, these were replaced by kola that came by sea from the (British) Gold Coast and Sierra Leone, thus bypassing (German) Togoland and (French) Benin. These imports reached a peak of 9,679 tons in 1924, but this trade, too, was doomed in the rapidly changing conditions of the colonial era. By the 1930s, imports declined as southern Nigeria began to satisfy the markets of northern Nigeria, after the introduction of C. nitida into the southern half of the country.49

While trade declined on a regional level, production of kola on a national level increased dramatically in the 20th century. An estimated 20,000 metric tons of kola were produced in 1910; with C. nitida accounting for 16,000 tons of this amount, which probably represented the upper limit of total annual production in the pre-colonial period. Cheaper transport resulted in the rapid increase in demand and a corresponding expansion in production, which in Ghana alone reached over 9,000 tons in 1923–4. By 1955 Ivory Coast was exporting 16,500 tons of kola north to Mali.50

Production of Kola continued into the post-colonial period. Estimates of world production of kola in 1966 suggest a total of 175,000 tons, of which approximately 120,000 tons were produced in Nigeria. The trade in kola nuts remains considerable today, with a global production of 280,000 metric tons in 2016, of which Nigeria, the Ivory Coast, Cameroon, and Ghana produced 97%.51

From ‘Kola’ to ‘Cola’: the West African origin of the popular soft drink.

As knowledge of kola reached the outside world, the plant itself began to travel, reaching the Caribbean as early as the 17th century, apparently because of kola’s well-known property as “a medicinal prophylactic agent”.Its demand stretched across the Atlantic to the New World, especially in the Caribbean and South America, where it was consumed by enslaved Africans.52

Kola was marketed across the northern Atlantic world during the 19th century, first as a drug and then as a tonic.

Beginning in the 1850s, research was carried out by botanists, chemists, and pharmacists on some of the properties ascribed to the kola nut. Demand for kola nuts from the Gold Coast (Ghana) mounted in Britain, France, Germany, and the United States, where the nuts were employed in the production of “neo kola,” cola-based soft drinks, and pharmaceuticals. Exports from the Gold Coast to Britain rose from a few hundred kilograms in 1867 to over 9 tonnes in 1899.53

In Britain, a medical preparation known as ‘kola chocolate’ that combined kola with sugar and vanilla was administered to invalids and convalescents as early as the 1870s. After considerable experimentation in Britain, France, and the USA, kola became a basic ingredient in various potions that mixed kola with cocoa, coca, soda, and to improve poor-quality chocolate.54

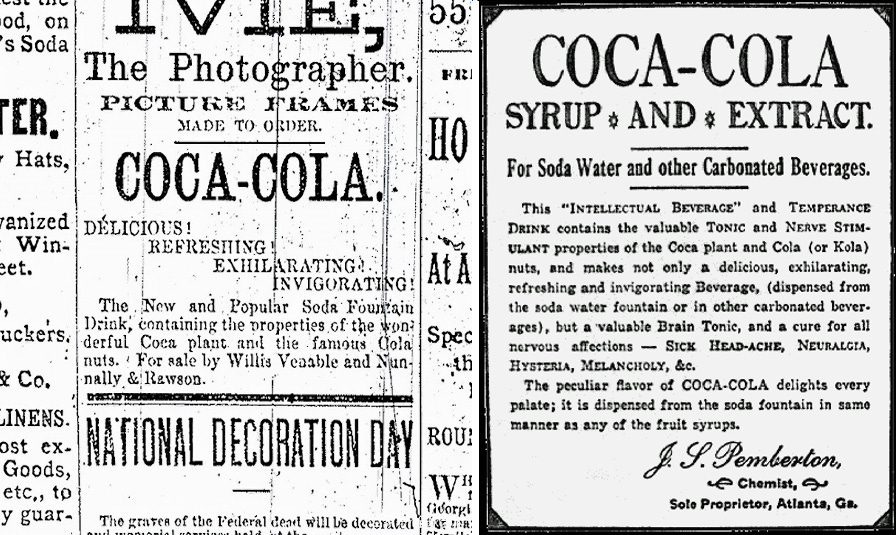

Kola extract was attributed with a variety of refreshing and restorative powers that ultimately resulted in the popular cola drinks. In 1886, the druggist John Pemberton of Atlanta, Georgia, invented Coca-Cola, which initially combined extracts from coca and kola, and was advertised as:

‘The New and Popular Soda Foundation Drink, containing the properties of the wonderful Coca plant and the famous Cola nut…

This Intellectual Beverage and Temperance Drink contains the valuable Tonic and Nerve Stimulant properties of the Coca plant and Cola (or Kola) nuts.”55

Some of the early advertisements for Coca-Cola. Atlanta Journal, May 29, 1886.

Caleb B.Bradham, a North Carolina pharmacist, created Coke’s principal rival, Pepsi-Cola, which combined sugar, vanilla, oils, spices, and kola. However, by the late 1890s, the companies had abandoned their medicinal claims and begun marketing them as a refreshment. Only the “forced march” tonic, a brand created by Burroughs Wellcome & Co. that was common in Britain, appears to have retained the original bitter taste of the Kola nut.56

The ingredients of Coca-Cola still contain the Kola nut extract, albeit in very small proportions.57 While modern advertising occasionally acknowledges this connection, most consumers remain largely unaware of the drink’s West African origins and the ancient long-distance trade networks that were sustained by the trade in Kola.

Evolution of the Coke bottle from 1899.

The diasporas that dominated intra-African trade also facilitated the movement of scholars. One such scholar was the theologian Muḥammad al-Wālī (fl. 1688) in the kingdom of Bagirmi (modern Chad).

al-Wālī was a rationalist whose writings combined classical philosophy and local oral traditions to challenge the ‘blind acceptance’ of religious authority.

The philosophical theology of Muḥammad al-Wālī is the subject of my latest Patreon article. Please subscribe to read more about it here, and support this newsletter:

Kola in the History of West Africa by Paul Lovejoy pg 110, 115. The French translations of al-Umari’s text, as well as Leo Africanus’ 16th century description of Songhay, make references to Kola that aren’t found in the English translations of the same texts by N. Levtzion and J. Hunwick. They are however, reproduced by P. LoveJoy and most Francophone West Africanists.

The Chronicles of Two West African Kingdoms: The Tārīkh Ibn Al-Mukhtār of the Songhay Empire and the Tārīkh Al-Fattāsh of the Caliphate of Ḥamdallāhi, edited by Mauro Nobili, Zachary V. Wright, H. Ali Diakité, pg 119

The Chronicles of Two West African Kingdoms: The Tārīkh Ibn Al-Mukhtār of the Songhay Empire and the Tārīkh Al-Fattāsh of the Caliphate of Ḥamdallāhi, edited by Mauro Nobili, Zachary V. Wright, H. Ali Diakité, pg 119, n. c, f)

Kola in the History of West Africa by Paul Lovejoy, pg 103-108)

Kola Trade and State-Building: Upper Guinea Coast and Senegambia, Fifteenth-Seventeenth Centuries by George E. Brooks, pg 3.

Evidence of an Eleventh‑Century AD Cola Nitida Trade into the Middle Niger Region by Nikolas Gestrich et al., pg 5-13

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by J. Hunwick, pg 132-133

The Chronicles of Two West African Kingdoms: The Tārīkh Ibn Al-Mukhtār of the Songhay Empire and the Tārīkh Al-Fattāsh of the Caliphate of Ḥamdallāhi by Mauro Nobili, Zachary V. Wright, H. Ali Diakité, pg 187, 241, 243. Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by J. Hunwick, pg 211.

Caravans of Kola: The Hausa Kola Trade, 1700-1900 By Paul E. Lovejoy pg 51

Kola in the History of West Africa by Paul Lovejoy, pg 115-116

The central Upper Guinea coast in the pre-contact and early Portuguese period, fifteenth to seventeenth centuries: The dynamics of regional interaction by Peter Mark, pg 120

The Portuguese in West Africa, 1415–1670: A Documentary History by M. D. D. Newitt, pg 215

Caravans of Kola: The Hausa Kola Trade, 1700-1900 By Paul E. Lovejoy pg 36

Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa by H. Barth

Sahara and Sudan Volume 2 By Gustav Nachtigal, translated by Allan George Barnard Fisher, Humphrey J. Fisher, pg 202

In the Heart of the Hausa States - Volume 2 by Paul Staudinger, pg 147

Consuming Habits Drugs in History and Anthropology, edited by Paul Lovejoy, Andrew Sherratt, Jordan Goodman, pg 103

Kola Production and Settlement Mobility among the Dan of Nimba, Liberia by Martin Ford

Caravans of Kola: The Hausa Kola Trade, 1700-1900 By Paul E. Lovejoy pg 2

History of the Upper Guinea Coast 1545–1800 By Walter Rodney, pg 206-208

Eurafricans in Western Africa: Commerce, Social Status, Gender, and Religious Observance from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century By George E. Brooks pg 14

Caravans of Kola: The Hausa Kola Trade, 1700-1900 By Paul E. Lovejoy pg 21-22)

Consuming Habits Drugs in History and Anthropology, edited by Paul Lovejoy, Andrew Sherratt, Jordan Goodman, pg 104

Eurafricans in Western Africa: Commerce, Social Status, Gender, and Religious Observance from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century By George E. Brooks, pg 50

Eurafricans in Western Africa: Commerce, Social Status, Gender, and Religious Observance from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century By George E. Brooks, pg 37-40

Eurafricans in Western Africa: Commerce, Social Status, Gender, and Religious Observance from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century By George E. Brooks, pg 7

Kola in the History of West Africa by Paul Lovejoy, pg 118

Eurafricans in Western Africa: Commerce, Social Status, Gender, and Religious Observance from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century By George E. Brooks, pg 47-49, 57, 75, 79-80)

Eurafricans in Western Africa: Commerce, Social Status, Gender, and Religious Observance from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century By George E. Brooks, pg 114, 284, 315. Kola in the History of West Africa by Paul Lovejoy, pg pg 117. The central Upper Guinea coast in the pre-contact and early Portuguese period, fifteenth to seventeenth centuries: The dynamics of regional interaction by Peter Mark pg 120-121)

Kola in the History of West Africa by Paul Lovejoy, pg 113

The Travels of Mungo Park in Africa by Mungo Park, published by J.M. Dent & Sons, pg 204-205

Travels Through Central Africa to Timbuctoo By René Caillié, published by Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley, pg 316-317, 323-324.

Travels Through Central Africa to Timbuctoo By René Caillié, published by Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley, pg 366-369, 418, 422, 456-457, 465-466.

Du Niger au Golfe de Guinée par le pays de Kong et le Mossi By Louis Gustave Binger pg 31, 129.

Warriors, Merchants, and Slaves: The State and the Economy in the Middle Niger Valley, 1700-1914 By Richard L. Roberts 23, 60-67

Caravans of Kola: The Hausa Kola Trade, 1700-1900 By Paul E. Lovejoy, pg 14

Asante in the Nineteenth Century: The Structure and Evolution of a Political Order By Ivor Wilks, pg 267-270

Caravans of Kola: The Hausa Kola Trade, 1700-1900 By Paul E. Lovejoy, pg 18-20

Caravans of Kola: The Hausa Kola Trade, 1700-1900 By Paul E. Lovejoy, pg 101-9,

Caravans of Kola: The Hausa Kola Trade, 1700-1900 By Paul E. Lovejoy, pg 118-126

Du Niger au Golfe de Guinée par le pays de Kong et le Mossi By Louis Gustave Binger pg 310-316. Caravans of Kola: The Hausa Kola Trade, 1700-1900 By Paul E. Lovejoy, pg 32-33, 59-62

Caravans of Kola: The Hausa Kola Trade, 1700-1900 By Paul E. Lovejoy, pg 42-44

Consuming Habits: Drugs in History and Anthropology, edited by Paul Lovejoy, Andrew Sherratt, Jordan Goodman, pg 103

Kola Nut in Africa and the Diaspora by Shantel A. George, Consuming Habits Drugs in History and Anthropology, edited by Paul Lovejoy, Andrew Sherratt, Jordan Goodman, pg 106-112

Consuming Habits: Drugs in History and Anthropology, edited by Paul Lovejoy, Andrew Sherratt, Jordan Goodman, pg 114

In the Heart of the Hausa States - Volume 2 by Paul Staudinger, pg 145-146

Consuming Habits: Drugs in History and Anthropology, edited by Paul Lovejoy, Andrew Sherratt, Jordan Goodman, pg 117

Cross-Boundary Traders in the Era of High Imperialism: Changing Structures and Strategies in the Sierra Leone-Guinea Region by Allen M. Howard

Consuming Habits: Drugs in History and Anthropology, edited by Paul Lovejoy, Andrew Sherratt, Jordan Goodman, pg 106

Consuming Habits: Drugs in History and Anthropology, edited by Paul Lovejoy, Andrew Sherratt, Jordan Goodman, pg 106, Kola in the History of West Africa by Paul Lovejoy pg 124-126

Kola in the History of West Africa by Paul Lovejoy, pg 124-125, Evidence of an Eleventh‑Century AD Cola Nitida Trade into the Middle Niger Region by Nikolas Gestrich et al., pg 1)

‘Kola Nut’ in The Cambridge World History of Food, edited by Kenneth F. Kiple, pg 688. Kola Nut in Africa and the Diaspora by Shantel A. George

‘Kola Nut’ in The Cambridge World History of Food, edited by Kenneth F. Kiple, pg 687-688)

Consuming Habits: Drugs in History and Anthropology, edited by Paul Lovejoy, Andrew Sherratt, Jordan Goodman, pg 107

For God, country, and Coca-Cola: the unauthorized history of the great American soft drink and the company that makes it by Mark Pendergrast, pg 26, 31-32

Consuming Habits: Drugs in History and Anthropology, edited by Paul Lovejoy, Andrew Sherratt, Jordan Goodman, pg 107. For God, country, and Coca-Cola: the unauthorized history of the great American soft drink and the company that makes it by Mark Pendergrast, pg 66-67. Kola Nut in Africa and the Diaspora by Shantel A. George.

For God, country, and Coca-Cola: the unauthorized history of the great American soft drink and the company that makes it by Mark Pendergrast, pg 121-124, 422-423

I'm a heavy soda drinker and had heard of the kola nut, but the different spelling in English obscured the connection...

thank you, I learned something!

Fascinating how the ecological interdependence created these centuries-old networks way before external demand for gold even mattered. The part about how colonial borders turned cross-ecological trade into "smuggling" overnight is kinda heartbreaking when you think about how Dyula traders ended upwith scars from chasing bullets and thorns just to keep doing what their families had done for generations.