Who Built Engaruka? (ca. 1400-1800): Stone Architecture and Historical Controversies in Eastern Africa

During the 15th century, a community of Iron Age farmers constructed an extensive landscape of stone-terraces, stone-lined fields, house platforms, stone circles and irrigation canals covering over 2,000 ha at the site of Engaruka in what is today Northern Tanzania.

The remains of this complex irrigation system, with its carefully engineered artificial sediment traps built over several centuries, have drawn considerable attention as some of the best examples of intensive agriculture in pre-colonial Africa.

As one early excavator of the site remarked: “At a distance, the extreme regularity and precision of the paths and terraces is strangely reminiscent of an amphitheater.”

Like many of Africa’s ancient stone ruins, the site of Engaruka became a magnet for pseudoscientifc theories associated with the “Hamitic” myth during the colonial period.

Although these theories have been disproven by modern archaeological research, they continue to shape popular debates concerning the origins of the site and the identity of its builders.

This article outlines the history of Engaruka and examines the controversies regarding its origin and abandonment.

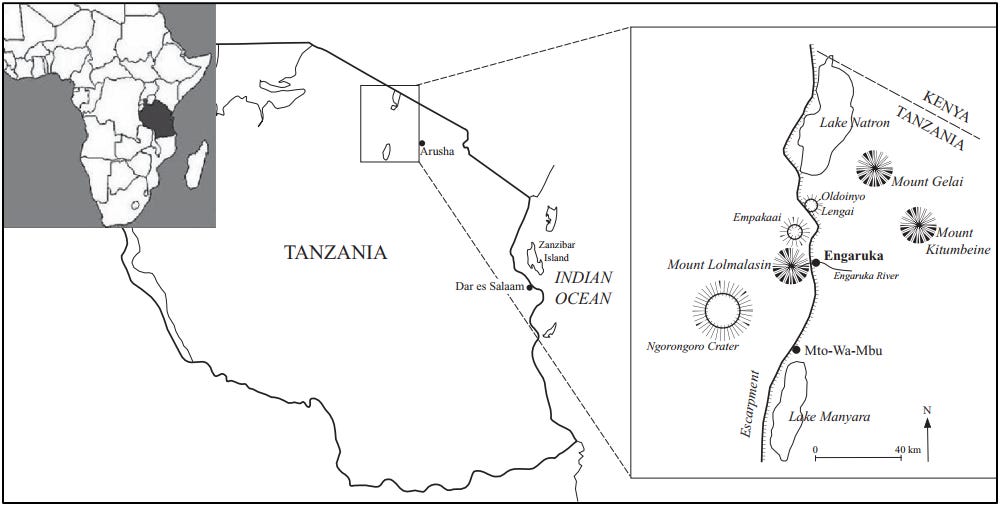

Map of Tanzania and the Engaruka area.1

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by joining our Patreon community. Subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Description of site:

Engaruka is situated at the foot of the western wall of the Great Rift Valley in Northern Tanzania. Precipitation around the site is low, but its water supply is augmented by the rivers that descend the escarpment, of which the only permanent one is the Engaruka River (Olkeju Leng’aruka, meaning ‘the river of leeches’).2

The archaeological remains at Engaruka stretch for 9 km along the escarpment foot and the adjacent part of the rift floor. The whole field system was artificially watered by small canals or furrows, originating from the perennial Engaruka river, as well as seasonal streams that descend the rift escarpment.

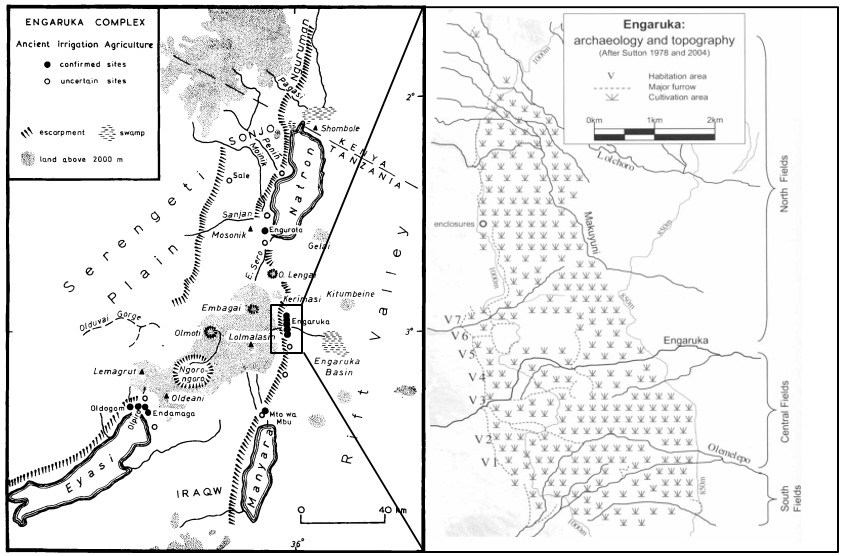

(left) The Engaruka Complex by J. E.G. Sutton. (right) Archaeological and topogaphical map of Engaruka by Daryl Stump

The area covered by stone-built ruins is divided into four sections: the hillside structures, also known as the North Fields, and the valley ruins, which are further divided into the Central and South Fields.

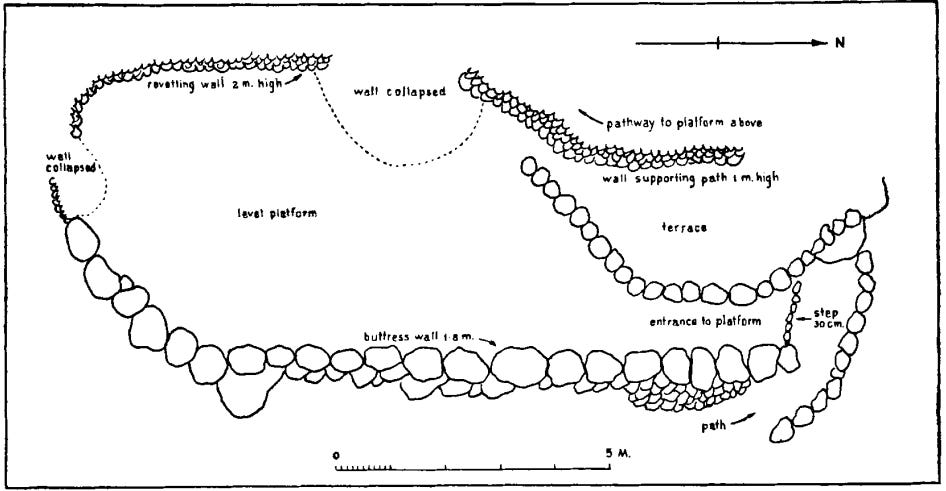

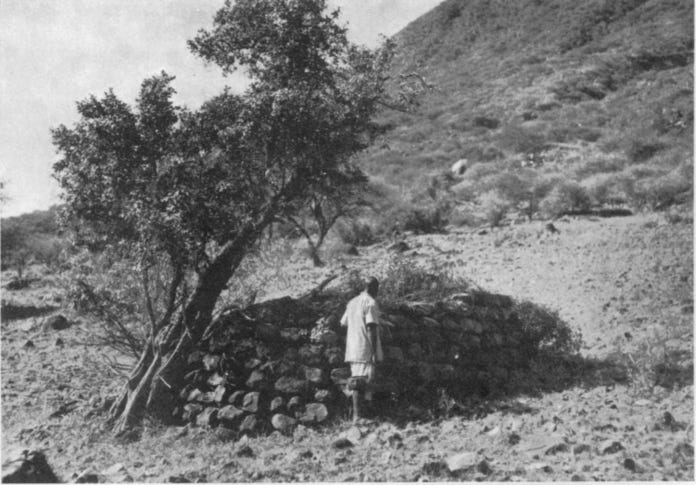

The North Fields, which mostly lie north of the Engaruka River, consist of several hundred terrace platforms cut into the hillside and built up with dry stone walling, with a floor shape of approximately 8x5 m. The rear wall of the terrace is revetted with dry stonework to a height of 3m. The terrace platforms have an entrance/exit at one end, which leads to paths going up and along the top of the revetting wall to the next platform.3

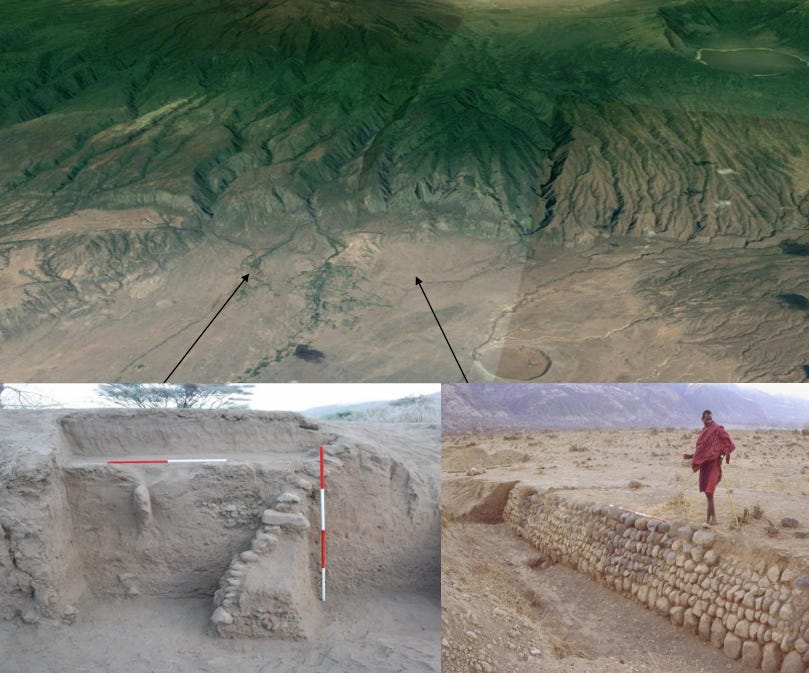

Detail of the escarpment, looking north-west from the direction of the present Engaruka village. The gorges of several dry gullies are prominent, as well as the deeper one cut by the Makuyuni river (on the right). The foreground and middle distance (between the catnera and the escarpment foot) is entirely within the area of ancient fields. Image and Captions by J. E. G. Sutton. (1978)

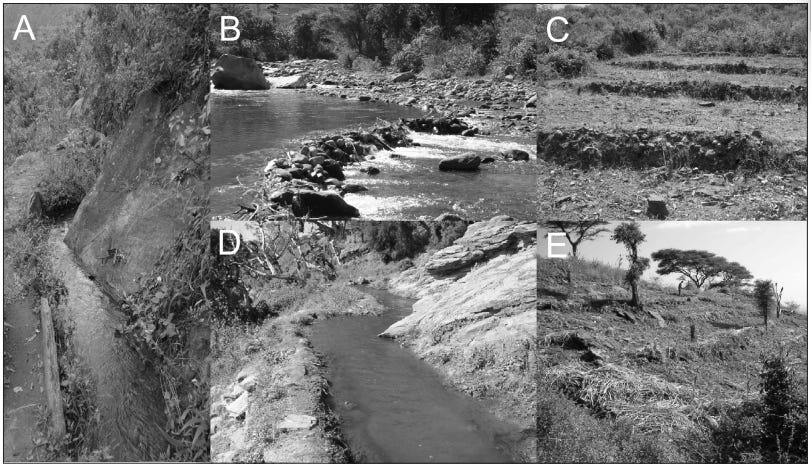

Engaruka dams and canal, images reproduced by R Marchant.4

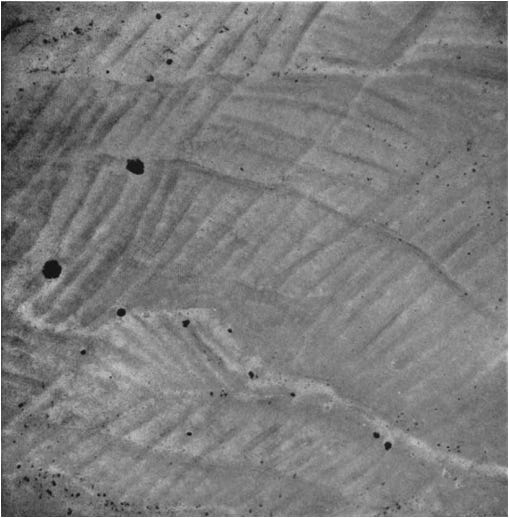

Northern field system. Image by Hamo Sassoon (1964)

Plan of Hillside structure A.1. Image by Hamo Sassoon

section with stone revetments in situ, and check-dam wall at Engaruka, image by R. Marchant

Irrigation canal at Engaruka. image by R. Marchant

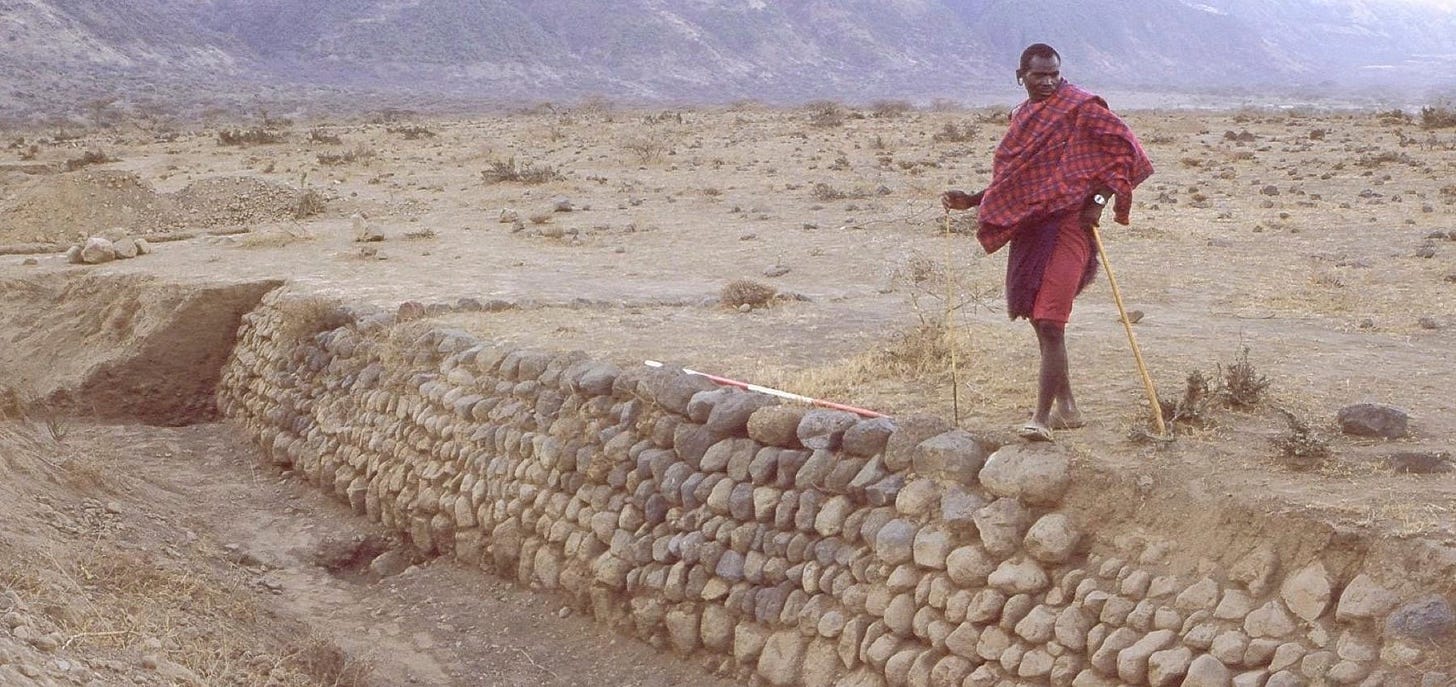

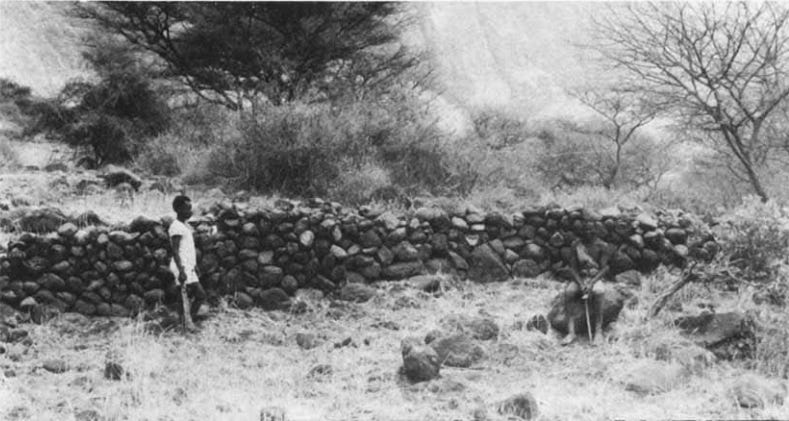

The buttress wall supporting the terrace platform on one of the hillsides. There are several hundred of these platforms representing an immense amount of labour. Image and Caption by Hamo Sassoon. (1966)

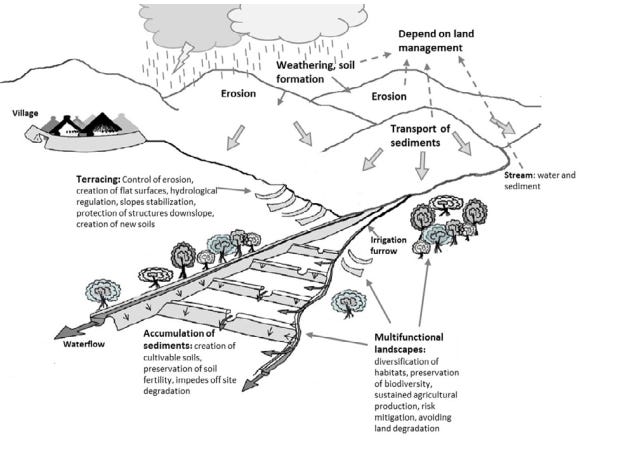

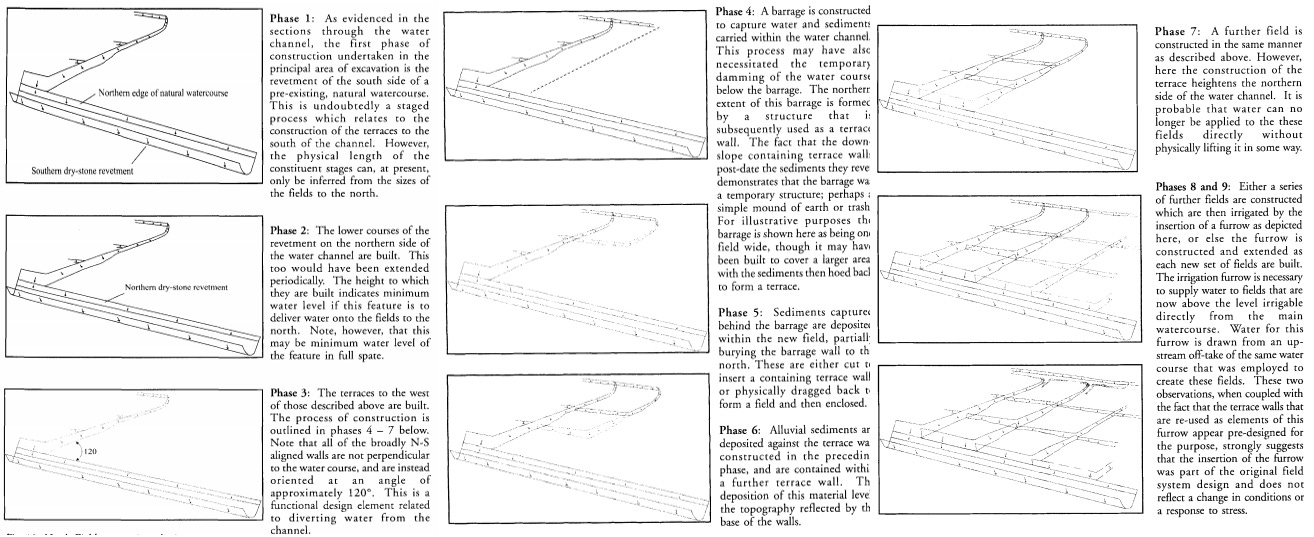

The presence of deep deposits of alluvial gravels behind the dry-stone revetting structures suggests that the walls were inserted to straighten and strengthen the sides of a preexisting natural watercourse. The sequence of field construction evident from intersections where the water channel meets its irrigation furrows suggests that the stone walls were built in phases, and that the terraced area was expanded gradually.5

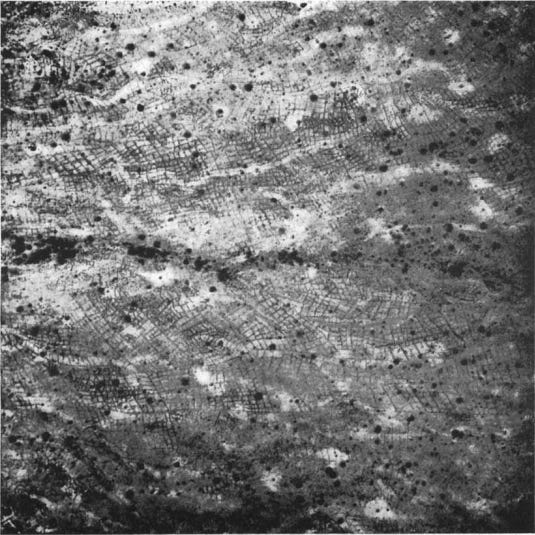

Most of the fields at Engaruka were built by capturing vast amounts of alluvial sediments behind thousands of drystone check dams. Stratigraphic data identify successive construction phases of the sediment trap walls, repeated capture of alluvial sediments, and utilisation of artificial channels and canals for crop irrigation. The rhomboid-shaped field sizes employed the characteristic 120-degree angle necessary to divert water and capture entrained sediments from the main channel.6

Graph of the main system functions and the ecosystem services involved in sediment harvesting systems. Illustration by Daryl Stump.

North Fields excavation phasing. image and captions by Daryl Stump.

Excavations indicate that the community that built the site was supported by the cultivation of irrigated sorghum fields supplemented by the husbandry of small and large stock, the manure from which may have been collected to help maintain soil fertility. These conclusions were based on the recovery of carbonised sorghum grains throughout the hillside depositional sequences, and the faunal assemblage that included remains of cattle and small stock.7

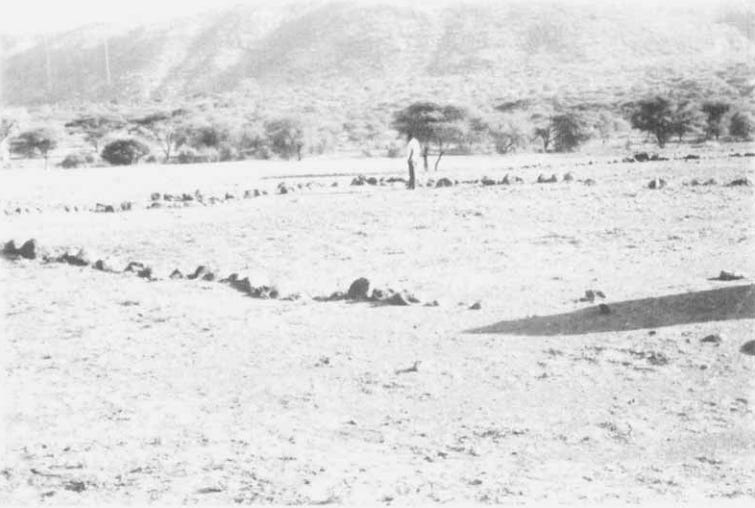

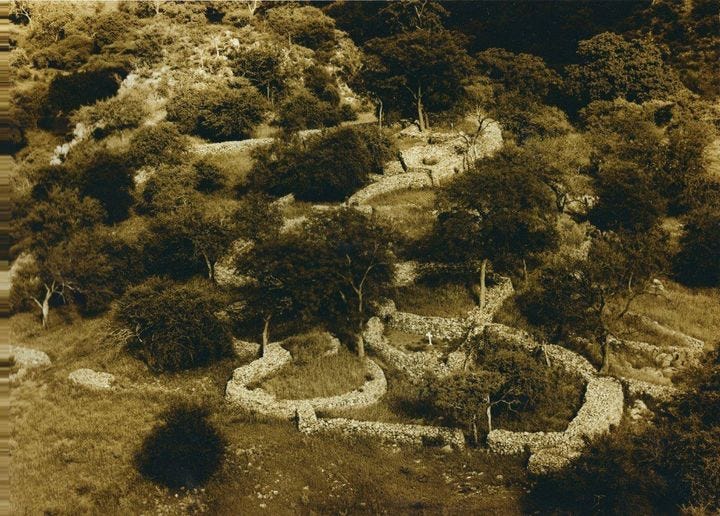

The valley ruins (Central and South fields) consist principally of stone cairns, stone circles, and an extensive network of low terraces south of the Engaruka River.

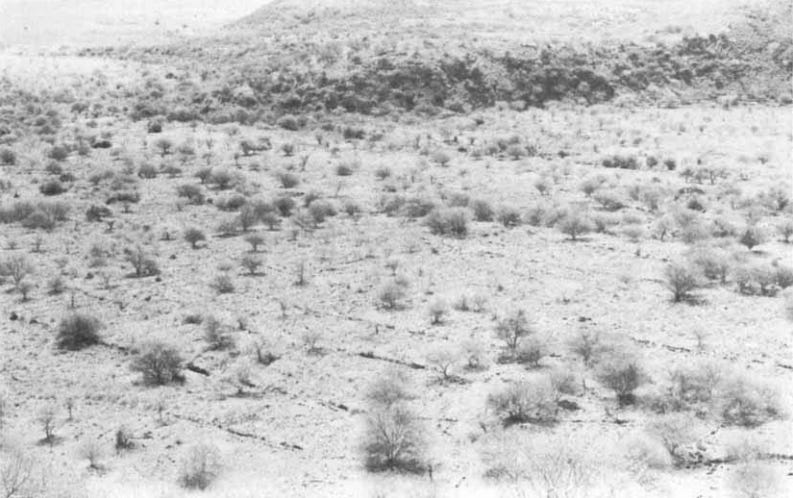

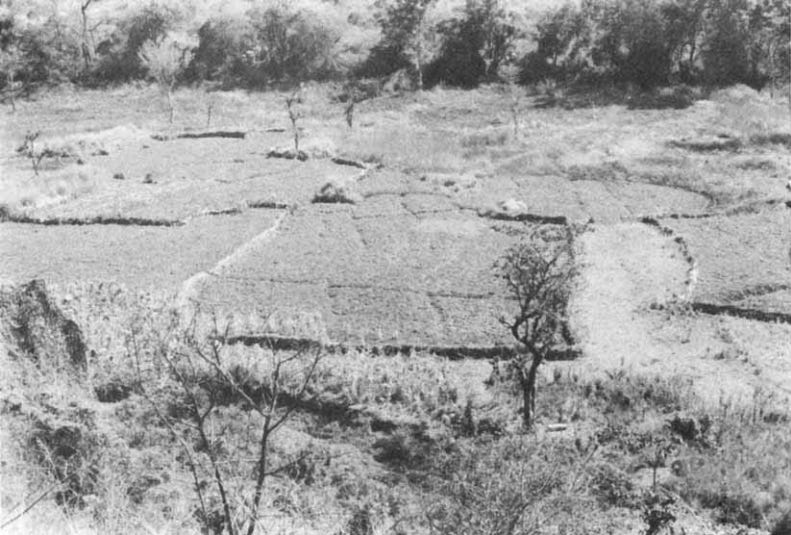

The Central Fields contain simple lines of medium to large stones forming sub-square divisions that appear as a parallel grid pattern when viewed from above, with the network of furrows dissecting them at right angles. The south fields consist of levelled plots with furrow lines and terraces that were frequently modified to improve the efficiency of the irrigation.8

The stone cairns vary from low piles of stones to considerable structures built with selected, graded, angular or rounded boulders, sometimes nearly 2m high and 5m long. The stone circles are more widely scattered than the cairns, but are constructed in the same way. A typical example had an internal diameter of 9m; the thickness of the wall was 2m at the base, and the height of the wall was 1.4 m above ground level.9

A stone cairn. showing the strongly built upper shell, which was filled with smaller stones. Image and Caption by Hamo Sassoon. (1966)

The outer wall of stone circle C1. Image by Hamo Sassoon. (1966)

Stone circles at Engaruka. Image by NgorongoroConservationAreaAuthority

Stone circles at Engaruka. Image by TanzaniaTourism

Excavations of the stone circles demonstrated that furrows and field boundaries were diverted around them, or cut through them, suggesting that the circles were earlier constructions that predate the division of the Central Fields area into irrigated cultivation plots. Sutton, Robertshaw, and Stump favour the interpretation of these sites as stock enclosures, based on the lack of internal post-holes (used for roofing houses), and the slightly elevated phosphate levels within and around these features.10

Stump’s excavations showed that stone lines, which cut through these structures, were not similar to the terraces, but were divisions of land. He suggests that they served as a means of demarcating ownership or cultivation rights. Similar examples of extant stone lines and associated cairns in the Buvuma islands of Lake Victoria (S.E. Uganda) are used to demarcate fields, or to connote ownership/tenure, as is the case for Usambara (N.E. Tanzania) and the lineage division of land into agricultural plots among the Pokot and Marakwet (N.W. Kenya).11

View eastwards from the northernmost of the seven ancient village sites, showing grid pattern of fields immediately below. At right angles to the furrows in the near distance are numerous narrow strip-divisions representing the individual cultivated plots, each with a low terrace wall. These fields were irrigated by water from the now dry gorge to the right. Image and Captions by J. E. G. Sutton. (1978)

Divided fields at Engaruka, image from TanzaniaUnforgettable

South fields: long embanked furrows north of Olemelepo bed. Image by J. E. G. Sutton. (1998)

Fields and field walls before excavation, Engaruka, South Fields, 2009. Photo by Vesa Laulumaa

Engaruka Fields, image by TanzaniaTourism

The mosaic of the Engaruka fields towards the southern extremity, on the lower part of the outwash of the Olemelepo river. Image and Captions by J. E. G. Sutton. (1978)

The people inhabiting Engaruka lived on raised, terraced platforms above the cultivated fields. These human habitations were constructed with wood and thatch and stood on drystone platforms, of which around 1,745 have been identified, some with associated fireplaces. They consisted of seven concentrations of numerous old homesteads built on the lower part of the steep escarpment scree, just above the highest field terraces. The settlement was defended by a stout drystone terrace wall, preserved 2m high in some cases.12

Linear wall, probably a late defensive device, in upper fields near to the south bank of the Engaruka River. Image and Captions by J. E. G. Sutton (1978)

(left) The partly paved interior of one of the small hut enclosures. (right) A fireplace excavated inside the entrance of one of the small hut enclosures. images and captions by Hamo Sassoon. (1966)

On the basis of the available radiocarbon determinations, the hillside settlements to the immediate south of the Engaruka River were in use in the early 1400s, peaked between 1620 and 1720 CE, and declined in the early half of the 1800s. The site itself had a considerably longer history of human occupation, but the irrigation system was established much later.13

Ancient stone ruins and Hamitic myths: historical debates on the builders of Engaruka.

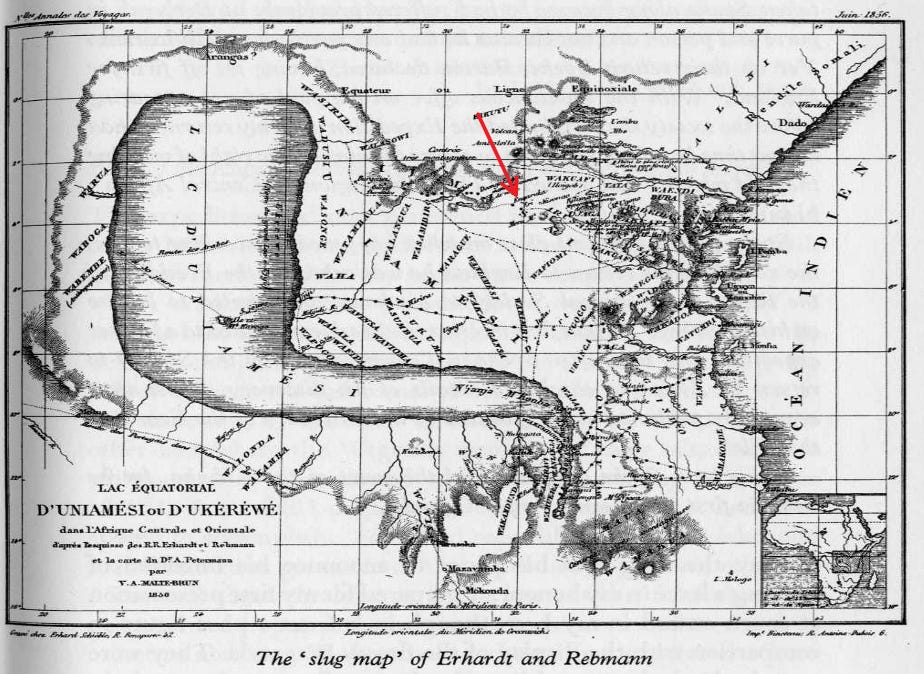

Engaruka first appears in written accounts on the so-called ‘slug map’ made in 1855 by two German missionaries at the east African coast, based on information obtained from “Representatives of various inland tribes—and Mahomidan inland traders.” It is indicated as a village along one of the caravan routes between the coast and the mainland.

However, the site had been abandoned by the time of the first written accounts in the late 19th century, and was inhabited by a section of Maasai herders who had partially displaced another group of herders known as the Tatoga/Datooga.14

Engaruka on the so-called ‘slug map’ of Erhardt and Rebmann. ca. 1855

The german traveler Gustav Fischer, who visited the site in 1883, noted that there were peculiar masses of stone, rising to a height of ten feet, and compared them to the walls of ancient castles. The ruins were mentioned in 1901 by Schoeller, who wrote: “In the mountains there are numerous stone circles and stone dams which are not connected with the present inhabitants.” In 1904, Jaeger and Uhlig wrote: “The remains of stone buildings which Uhlig and I found near Engaruka at the foot of the Great Rift Wall are apparently attributable to the Tatoga.” (ie; Datooga, a Nilo-Saharan speaking group).15

Semi-professional surveys of the site were conducted by paleontologists, beginning with Dr. Hans Reck (1913), who, ‘On ethnographic rather than anatomical grounds … ascribes the Engaruka graves to a Hamitic nomadic tribe.’ This claim was repeated in 1935 by Dr. Louis Leakey, whose maasai informants attributed the terraces to the Wambulu (ie; Iraqw’ar, a Cushitic-speaking group) who lived south of the site.16

However, their conclusions were contradicted by the anthropologist H. A. Fosbrooke (1938), who compared Engaruka on material groups to the stone-works of the Sonjo (a Bantu-speaking group) who lived just north of the site. Having participated with Leaky during his surveys of the site, he pointed out that Leaky’s informants may have confused the Wambulu with the Wambugwe (a Bantu-speaking group neighbouring the Iraqw’ar) because the Masai appellation ‘Il-Datwa’ could refer to either.17

Sites of intensive agriculture in Eastern Africa. Map by M. I. J. Davies. Note the location of Engaruka relative to the Sonjo and Iraqw’ar.

The first professional archaeological studies of the site were conducted by Neville Chittick (1958, 1962), who was unable to find any Iraqw’ar tradition of the tribe having come from the Engaruka area. Excavations by Hamo Sassoon (1966, 1966) found hut remains with fireplaces, local pottery, and iron objects, but very few imported ornaments. He suggested that the material culture of Engaruka, while local in origin, isn’t sufficient to draw comparisons with neighbouring groups, but notes some similarities with the irrigation systems of the Sonjo and the Chagga of Kilimanjaro.18

Sutton (1978) noted the similarities between Engaruka and extant Sonjo villages, especially in the paved-house-on-terrace platforms of the Sonjo, their strikingly similar fireplaces, and their irrigation system, but didn’t rule out the Iraqw’ar connection, suggesting that the Engaruka community was heterogeneous.19 He repeats this this theory of Engaruka’s heterogenity (1998) but ultimately leaned more towards the Sonjo connection (2004). Observing the presence of old Sonjo ruins dating back to the late period of Engaruka, he concludes that “it is at Sonjo in particular that cultural continuity from the old Engaruka experience seems discernible.”20

Studies of Engaruka’s pottery by Sutton (1978) Robertshaw (1986), Siiriainen (2003), and Sutton (2004) confirmed its local origins, but connections with neighbouring groups were inconclusive. 21

Sassoon had noted that pottery in the modern settlement near Engaruka was imported from Kondoa, some 200km south. Recent petrographic analysis of pottery from the archaeological settlement by Oteyo & Doherty (2009) showed that it too may have been imported from the Kondoa or Sonjo regions. The Sonjo connection has since received further support on ethnographic and archaeological grounds by Kadalida (2021)22

Given the trajectory of the aforementioned research, more recent studies of the Iraqw’ar farming by Lowe Börjeson (2004, 2007) havent examined the Engaruka connection. While the Iraqw’ar irrigation system is similar to that found in Sonjo and Engaruka, save for the limited use of stone, descriptions of their domestic structures don’t include the paved house structures and fireplaces common to both the Sonjo and Engaruka.23

Linguistic research by Derek Nurse (1993) suggests that the irrigation system of the Sonjo and Engaruka itself was set up in situ, rather than being brought from elsewhere. He connects the archaeological settlement to the Sonjo rather than Iraqw’ar, noting that “no existing Southern Cushitic community appears to practise or have practised irrigation on this scale anywhere in East Africa,”24 the latter being the exception.

It’s relevant to note that the use of stone architecture in eastern and southern Africa was of particular interest to colonial scholars, in part due to pseudo-scientific theories such as the Hamitic hypothesis.

These theories have since been disproven, largely through archaeological research conducted in the 1930s for the ruins of Great Zimbabwe, and in the 60s and 70s for the stone ruins of South Africa and western Kenya, whose material culture and dating conclusively showed that they were built by local, African communities.

Additionally, the ubiquity of such stone ruins, now known to number over a thousand in Zimbabwe, Botswana, South Africa, and Mozambique, and over a hundred along the eastern shores of Lake Victoria in western Kenya, shows that stone architecture was fairly common in eastern and southern Africa. This is especially relevant considering that the ruins of Thimlich Ohinga in western Kenya are frequently compared to the Zimbabwe ruins.

Great Zimbabwe ruins, Zimbabwe.

Thulamela ruins, South Africa

Sampowane ruin in Botswana.

Manyikeni ruins, Mozambique.

Thimlich Ohinga, Kenya.

For Engaruka, Louis Leakey’s population estimate of ‘thirty to forty thousand’ popularized the idea that the settlement represented a vanished ‘city’. Other writers, influenced by the accounts of drystone terraces of the Marakwet (in N.W. Kenya) and later at Engaruka, claimed they were part of an ancient ‘Azanian civilization’ of Hamitic stock, supposedly because the present inhabitants were too “barbarous to have learned it themselves.” Others imagined the sites as a useful link in a ‘megalithic’ chain along the highland spine of the continent, all the way from Ethiopia to Zimbabwe.25

Early theories about the Iraqw’ar connection to Engaruka were partly based on the tribe’s supposed ‘Hamitic origin’ from the north. But as early as the 1950s, most professional archaeologists considered these claims unfounded, and have subsequently leaned more towards the Sonjo connection, besides identifying that such stone terraces were, after all, not exceptional in eastern and southern Africa (see below), nor were they only found among specific ethnicities or population groups.

In non-specialist circles, this association persists in part because of misconceptions surrounding the origins of the Iraqw’ar. In modern literature, the spelling of their name has been retrospectively reimagined as evidence of a supposed origin in Iraq, despite the absence of historical or linguistic support.

The anthropologists Roberth Thornton (1980) and Ole Bjørn Rekdal (1998) have conclusively shown that the Iraq origin of the Iraqw’ar is a modern myth popularized in the 1950s. The very first descriptions of the ‘Iraku’ or ‘Erokh’ by Baumann (1894) and Bagshawe (1923, 1925) make no mention of this connection, the latter infact, claimed that the group came from around Lake Victoria, in the west. Subsequent anthropological research in the 1930s provided no evidence of oral traditions mentioning an origin from Iraq, nor from any region in the north.26 [something which was already noted by Chittick during the first professional surveys of Engaruka].

The various versions of the historical traditions about the Iraqw’ar original homeland of Ma’angwatay are consistent in claiming that the group came from the south (in central Tanzania), specifically among the Alagwa, Burunge and the Rangi, who currently live considerably further south than the lraqw. None trace their origin to the north of Mbulu; ie, in the direction in which Engaruka is located.27

As Sutton argues; the Iraqw’ar were not “a simple relic of the situation before the expansion of both Nilotes and Bantu” their emergence as distinct group and their “agricultural adaptation to the hills of Mbulu district are very recent developments.”28 The Iraqw’ar are the descedants of multiple groups with over 150 clans, of which only three clans trace their origins to Ma’angwatay, the rest being of mostly Tatoga/Datooga (Nilotic) origin, who were predominantly herders like the Masaai. The Iraqw’ar historical traditions are themselves no older than the 18th century, by which time Engaruka was in decline.29

The ‘Hamitic’ myths were also influenced by the paucity of archaeological research in East Africa, with Engaruka at the time being the only late-Iron-Age site in the interior to have been studied in sufficient detail before the end of the colonial period. Subsequent research, however, showed that both stone architecture and pre-colonial irrigation systems were fairly common across eastern and southern Africa.

Gravity-fed irrigation systems employing the same principles as at Engaruka exist to this day in several places in northern Tanzania and Kenya.

In the east, they are especially frequent among the Chagga on the slopes of Kilimanjaro and the Pare on the surrounding mountains of Pare and Usambara. Along the west scarp of the Rift, the terraces of the Sonjo villages have been noted for their likely connection with Engaruka; to the south are the irrigated fields of the Iraqw’ar, while much further to the north, the Engaruka situation is recalled most closely by the Pokot and Marakwet (N.W. Kenya) where canals are led off a series of rivers descending the steep escarpment.30

Irrigated fields of the Sonjo village of Rokhari (Kisangiro). The fields occupy a long, narrow river valley, the river itself being hidden from view by the steep hillside in the foreground. Image and Captions by J. E. G. Sutton (1978)

“An Iraqw field landscape” by Hartley 1938. Image by Lowe Börjeson

Irrigation systems of the Pokot and Marakwet in N.W Kenya. A. Stone lined irrigation canal, Pokot. B. Dam and intake canal, Pokot. C. Stone terracing, Pokot. D. Irrigation canal, Marakwet. E. Simple ‘trash’ terracing, Marakwet. Images by M. I. J. Davies.

While the immediate neighbours of Engaruka (the Sonjo and Iraqw’ar) did not use stone as frequently as Engaruka, this was largely due to the latter site having sufficient stone resources in the form of loose lava rock, alluvial boulders, and pebbles.31

Single-faced dry-stone revetments can be found about 150km east of Engruka, among the South Pare settlements, while freestanding, double-faced walls of terraces are found in the North Pare settlements at Lemebeni, and have been compared to the more extensive and older stone terraces much further south in Inyanga (Zimbabwe).32

Abandoned terraces at Lembeni, North Pare, Tanzania (left) and Vudee, South Pare, Tanzania (right). Images by Daryl Stump

Comparative analysis of Engaruka and similar stone-terraced sites across southern Africa

Recent studies have drawn comparisons between **Engaruka (total estimated size of 2,000 ha) and similar stone-walled irrigated landscapes across southern Africa, especially the much larger and older stone terraces of Inyanga in Zimbabwe that cover about 22,000 ha, and the Bokoni ruins of South Africa that cover over 1,000,000 ha.33

**Engaruka is therefore not “the largest abandoned system of irrigated agricultural fields and terraces in sub-Saharan Africa,” as is often asserted. Such claims inadvertently echo the colonial-era tendency to exaggerate the significance of particular sites at the expense of broader regional comparisons.

Terraces and stone ruins of Inyanga, Zimbabwe. images by Plan Shenjere-Nyabezi

Remains of stone terraces, roads, agricultural fields and household compounds at Bokoni, South Africa. image by Graeme Williams.

Bokoni terraces. Image by Riaan de Villiers

The extensive use of stone architecture at these three sites is evidence of high labour inputs in terms of construction and maintenance, and is central to discussions regarding the intensity of cultivation, the level of surpluses produced, and the size of population they supported.

Excavations at all three sites point to broad similarities in terms of agronomy: all combined the cultivation of cereals with the keeping of small and large stock, and integrated the two elements of this system by manuring arable fields or by allowing domestic animals to graze on harvested areas. The sites of Bokoni and Inyanga were also built in stages by relatively small communities, which periodically moved around the landscape, rather than by a large population occupying the whole site.34

Four stages in the development of a substantial bokoni type of terrace

For archaeologists and historians who study these ancient settlements, the fact that stone was used in construction is of great help, since they can be easily identified in satellite images and aerial photographs, and their spatial arrangements can be analyzed. This is especially relevant for debates concerning the use of intensive agricultural technologies in pre-colonial Africa.

Agriculture in Africa south of the Sahara is usually characterized as ‘extensive’, in which production is increased by expansion of farmed land, rather than intensification.

However, this simplistic but enduring image of African farming is contradicted by the historical and contemporary evidence for the variety of African land-use patterns and agricultural systems; the longevity of farming on relatively permanent tracts of land in densely populated regions; and the existence of intensive systems of farming such as terracing in different parts of the continent.35

The construction and later abandonment of irrigated landscapes of Engaruka, Inyanga, and Bokoni is often thought to have been related to population pressure.

Most explanations rely on two separate models that were universally applied to many abandoned ancient sites around the world: the neo-Malthusian model that links rising population to resource degradation, and the expansionist model in which communities develop technologies in response to land shortages. Both often assume that physical remains associated with agriculture can be easily equated with greater labour expenditure.

However, both models have been criticized, primarily by historians, for their evidently mechanistic and reductive explanations for what were complex historical processes. The main criticism is that most of the sites were built incrementally by small populations, rather than singularly by large populations, hence requiring lower population densities than previously suggested.36

As summarised by Lowe Börjeson “the adoption of intensive farming practices is not necessarily associated with a long-term evolutionary process of intensification, occurring in the wake of population pressure. The tendency, in much literature on African agricultural history, to treat intensive farming as a late state in an evolutionary sequence, without support from empirical data, must therefore be attributed to a lax use of theory.”37

Additionally, most estimates for the population of Engaruka, especially the 30-40,000 produced by Leakey (1936) and the more recent 7,000-11,500, by Laulumaa (2006), assume that the whole settlement area was occupied simultaneously. However, the gradual sequence of construction and its fairly long occupation period over four centuries contradicts such assertions. Sassoon (1964) criticized these early estimates as exaggerated, suggesting instead that Engaruka’s population was as low as 2-4,000, by pointing out that modern towns like Arusha had a population of just 10,000 in the 1960s.38

In its heyday, Engaruka must have been a truly impressive sight; a flourishing oasis in the dry rift valley, with carefully controlled waters flowing through its stone-built furrows and into the extensive grids of levelled fields of standing sorghum and other crops, all overlooked by the series of neatly constructed nucleated villages.

Although it has often been asserted that the construction and maintenance of runoff systems were labour-intensive, recent simulations of the Engaruka system suggest that the construction of sediment traps could be managed at the household level, requiring the involvement of just a few individuals during a few weeks. There was also no evidence of soil nutrient depletion, which challenges the hypotheses of soil exhaustion for its abandonment.39

A number of explanations have been proposed to account for the abandonment of the site by the early 19th century.

According to Sutton, it is likely that the population of Engaruka was gradually absorbed into neighboring communities of farmers and herders. This interpretation is supported by Stump’s findings, which suggest that the stone circles, which were used as stock pens, belong to an early phase of occupation and indicate that Engaruka’s inhabitants alternated their subsistence strategies between herding and farming.40

The combined research shows that the Late Iron Age economy at Engaruka relied on hydrological and climatic conditions that are no longer in place.

Whatever the causes of its abandonment, the techniques that built and sustained the agronomy at Engaruka must be regarded as having achieved a degree of success. Its exceptionally well preserved ruins allow us to reconstruct the sophisticated agrarian technologies employed by pre-colonial farmers in eastern Africa.

Part of the southern system of stone-lined enclosures. Image by Hamo Sassoon. “At a distance, the extreme regularity and precision of the paths and terraces is strangely reminiscent of an amphitheater.”

Stone circle at Engaruka.

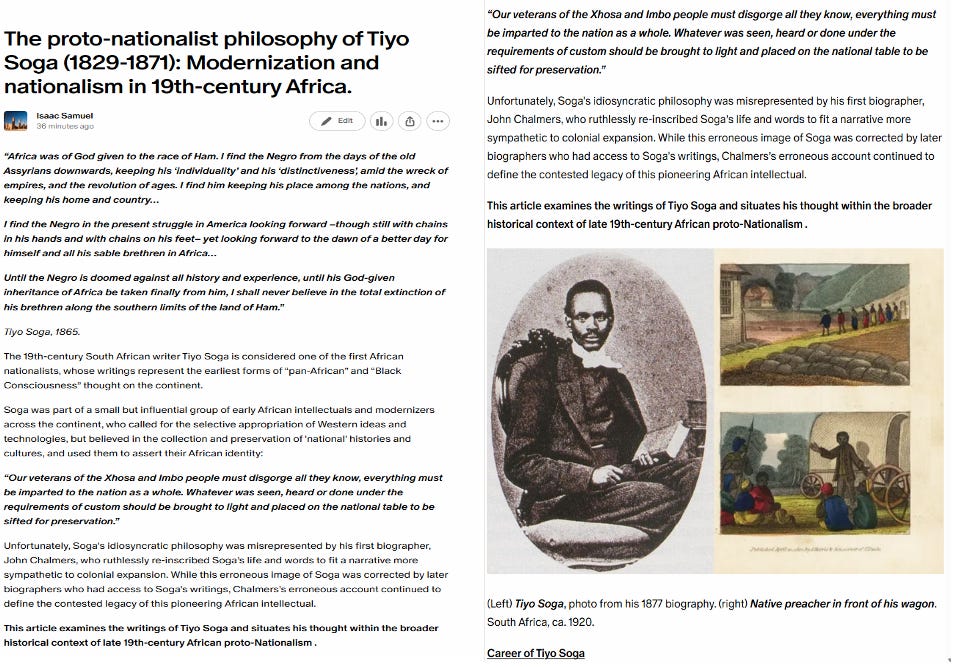

A century before the nationalist ideas of Tanzania’s Nyerere and Ghana’s Nkrumah, there were the writings of Samuel Johnson and Tiyo Soga (d. 1871).

These were pioneering African intellectuals who transformed the numerous ethnicities of pre-colonial Africa into larger nations with a shared history, language, and culture, which they situated in the universal history of Africa and the African diaspora.

The proto-Nationalist philosophy of Tiyo Soga is the subject of my latest Patreon article. Please subscribe to read more about it here, and support this newsletter:

Map by L-O Westerberg et al.

Engaruka and its Waters by J. E. G. Sutton, pg 40-42

Engaruka: Excavations during 1964 by Hamo Sassoon, pg 83-84)

KESHO: A participatory land use planning tool to trace past, present and future social ecological systems by Robert Marchant

The development and expansion of the field and irrigation systems at Engaruka, Tanzania, by Daryl Stump, pg 75-77

The development and expansion of the field and irrigation systems at Engaruka, Tanzania, by Daryl Stump, pg 82-83

The development and expansion of the field and irrigation systems at Engaruka, Tanzania, by Daryl Stump, pg 71, 73

Irrigation Agriculture in the northern Tanzanian Rift Valley before the Maasai era by Sutton, pg 14-15. The development and expansion of the field and irrigation systems at Engaruka, Tanzania, by Daryl Stump, pg 84, Engaruka: Excavations during 1964 by Hamo Sassoon, pg 1964, pg 85,

Engaruka: Excavations during 1964 by Hamo Sassoon, 1964, pg 84-85

The development and expansion of the field and irrigation systems at Engaruka, Tanzania, by Daryl Stump, pg 87-88

The development and expansion of the field and irrigation systems at Engaruka, Tanzania, by Daryl Stump, pg 89-90, Economic Specialisation, Resource Variability, and the Origins of Intensive Agriculture in Eastern Africa by Matthew I. J. Davies, pg 11-12

Engaruka and its Waters by J. E. G. Sutton, pg 43-44. From platforms to people: rethinking population estimates for the abandoned agricultural settlement at Engaruka, northern Tanzania by Matthew I.J. Davies pg 205-206

The development of the ancient irrigation system at Engaruka, northern Tanzania: physical and societal factors, pg 308-309. The development and expansion of the field and irrigation systems at Engaruka, Tanzania, by Daryl Stump, pg 73.

The development and expansion of the field and irrigation systems at Engaruka, Tanzania, by Daryl Stump, pg 73

Engaruka: Excavations during 1964 by Hamo Sassoon, 1964, pg 79. The development of the ancient irrigation system at Engaruka, northern Tanzania: physical and societal factors, pg 310

Engaruka: Excavations during 1964 by Hamo Sassoon, pg 80-81

Engaruka and its Waters by J. E. G. Sutton, pg 67-68

Engaruka: Excavations during 1964 by Hamo Sassoon, New Views on Engaruka, Northern Tanzania. Excavations Carried out for the Tanzania Government in 1964 and 1966 by Hamo Sassoon

Irrigation Agriculture in the northern Tanzanian Rift Valley before the Maasai era by John E.G. Sutton, pg 31-34.

‘Engaruka: An irrigation agricultural community in Northern Tanzania before the Maasai’ by J.E.G Sutton. ‘Engaruka: The success and abandonment of an integrated irrigation system in an arid part of the Rift Valley, c. 15thto 17chCenturies’’ by J.E.G Sutton. pg 127-130. ,in Islands of Intensive Agriculture in Eastern Africa byWidgren, M and J. E. G. Sutton (eds.)

The development and expansion of the field and irrigation systems at Engaruka, Tanzania, by Daryl Stump, pg 71-73

Petrographic investigation of the provenance of pottery from Engaruka by Gilbert Oteyo & Chris Doherty. Architects of the Engaruka Techno-Cultural Complex: Testing the Sonjo Connection by Penina Emanuel Kadalida.

A History under Siege Intensive Agriculture in the Mbulu Highlands, Tanzania, 19th Century to the Present by Lowe Börjeson. Boserup backwards? Agricultural intensification as ‘its own driving force’ in the Mbulu Highlands, Tanzania by Lowe Börjeson

The History of Sonjo and Engaruka: A Linguist’s View by Derek Nurse & Franz Rottland

Denying History in Colonial Kenya: the Anthropology and Archeology of G.W.B. Huntingford and L.S.B. Leakey by J.E.G. Sutton, pg 305, 315-316, n. 51. Irrigation and Soil-Conservation in African Agricultural History by J. E. G. Sutton, pg 30-31

When hypothesis becomes myth: The Iraqi origin of the Iraqw. by Ole Bjørn Rekdal. Space, Time, and Culture Among the Iraqw of Tanzania By Robert J. Thornton pg 199-200. Durch Massailand zur Nilquelle by Dr. Oscar Baumann (1894). The Peoples of the Happy Valley (East Africa): The Aboriginal Races of Kondoa Irangi by FJ Bagshawe.

When hypothesis becomes myth: The Iraqi origin of the Iraqw. by Ole Bjørn Rekdal, pg 34, n. 5. Space, Time, and Culture Among the Iraqw of Tanzania By Robert J. Thornton pg 196-207

Being Maasai Ethnicity & Identity in East Africa By Richard D. Waller pg 51-52.

Space, Time, and Culture Among the Iraqw of Tanzania By Robert J. Thornton pg 194-199.

Irrigation Agriculture in the northern Tanzanian Rift Valley before the Maasai era by Sutton, pg 28. Economic Specialisation, Resource Variability, and the Origins of Intensive Agriculture in Eastern Africa by Matthew I. J. Davies, pg 2-5

Irrigation and Soil-Conservation in African Agricultural History by J. E. G. Sutton, pg 38-39

Intensification in Context: Archaeological Approaches to Precolonial Field Systems in Eastern and Southern Africa by Daryl Stump, pg 272

Intensification in Context: Archaeological Approaches to Precolonial Field Systems in Eastern and Southern Africa by Daryl Stump, pg 256. Reading the Rocks and Reviewing Red Herrings by Peter Delius and Maria Schoeman.

Bokoni: Old Structures, New Paradigms by P Delius, T. Maggs, A. Schoeman, pg 405, ‘The Agricultural Landscape of the Nyanga Area of Zimbabwe’ by R. Sope,r pg 211-212

Irrigation and Soil-Conservation in African Agricultural History by J. E. G. Sutton, pg 27-30

Economic Specialisation, Resource Variability, and the Origins of Intensive Agriculture in Eastern Africa by Dr Matthew I. J. Davies, pg 6-8. Intensification in Context: Archaeological Approaches to Precolonial Field Systems in Eastern and Southern Africa by Daryl Stump, pg 262-264,

Islands of Intensive Agriculture in Eastern Africa by Widgren, M and J. E. G. Sutton (eds.) , pg 73

Intensification in Context: Archaeological Approaches to Precolonial Field Systems in Eastern and Southern Africa by Daryl Stump, pg 265-266, Engaruka: Excavations during 1964 by Hamo Sassoon, pg 97. From platforms to people: rethinking population estimates for the abandoned agricultural settlement at Engaruka, northern Tanzania by Matthew I.J. Davies)

People and Agrarian Landscapes: An Archaeology of Postclassical Local Societies in the Western Mediterranean. edited by Juan Antonio Quirós Castillo et al. pg 204, 208

The development and expansion of the field and irrigation systems at Engaruka, Tanzania, by Daryl Stump, pg 90-91. The development of the ancient irrigation system at Engaruka, northern Tanzania: physical and societal factors, pg 312-314

Most interesting; thank you. I really wish I could spend all my time reading all this new--to me--history from all over the world like I can now.

But, I'm a political commentator, too, and interesting times keep intruding. Which makes things like this even more necessary for me, I suppose. There's so much about African history I could never find in American libraries before, so I appreciate seeing this on Substack.