The stone ruins of South Africa: a history of Mapungubwe, Thulamela and Dzata. ca. 1000-1750CE.

The dzimbabwe ruins of south-eastern Africa are often described as the largest collection of stone monuments in Africa south of Nubia. While the vast majority of the stone ruins are concentrated in the modern countries of Zimbabwe and Botswana, a significant number of them are found in South Africa, especially in its northernmost province of Limpopo.

Ruined towns such as Mapungubwe, Thulamela, and Dzata have attracted significant scholarly attention as the centers of complex societies that were engaged in long-distance trade in gold and ivory with the East African coast. Recent research has shed more light on the history of these towns and their links to the better-known kingdoms of the region, enabling us to situate them in the broader history of South Africa.

This article outlines the history of the stone ruins of South Africa and their relationship to similar monuments across the region.

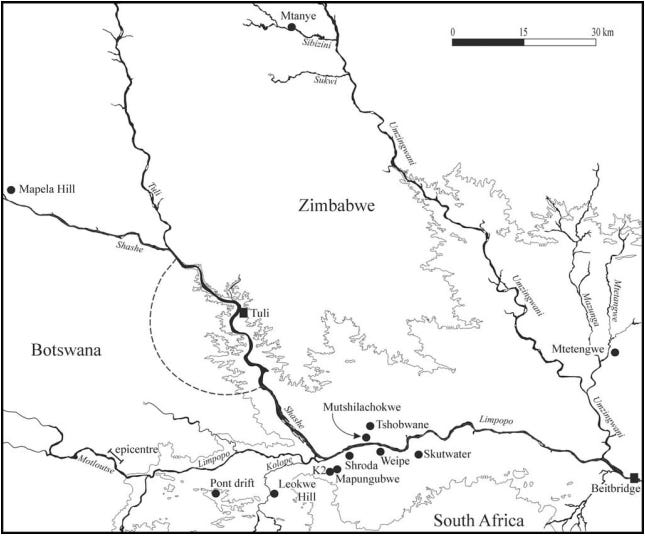

Map of south-eastern Africa highlighting the ruined towns mentioned below.1

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

State formation and the ruined towns of Limpopo: a history of Mapungubwe.

During the late 1st millennium of the common era, the iron-age societies of southern Africa mostly consisted of dispersed settlements of agro-pastoralists that were minimally engaged in long-distance trade and were associated with a widely distributed type of pottery known as the Zhizho wares. The central sections of these Zhizo settlements, such as at the site of Shroda (dated 890-970 CE) encompassed cattle byres, grain storages, smithing areas, an assembly area, and a royal court/elite residence, in a unique spatial layout commonly referred to as the 'Central Cattle Pattern'2.

By 1000 CE, Shroda and similar sites were abandoned, and the Zhizo ceramic style largely disappeared from southwest Zimbabwe and northern South Africa. Around the same time, a new capital was established at the site known as ‘K2’, whose pottery tradition was known as the 'Leopard’s Kopje' style, and is attested at several contemporaneous sites. The size of the K2 settlement and changes in its spatial organization with an expanded court area indicate that it was the center of a rank-based society.3

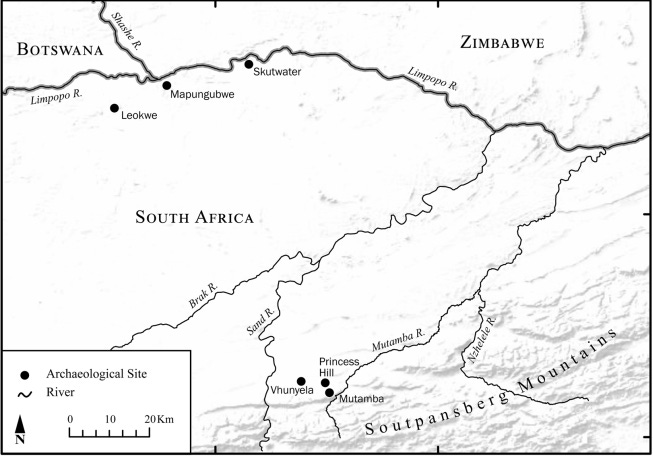

Map showing some of the earliest ‘Zimbabwe culture’ sites including Shroda, K2 and Mapungubwe in south Africa.4

Around 1220CE, the settlement at K2 was abandoned and a new capital was established around and on top of the Mapungubwe hill, less than a kilometer away. The settlement at Mapungubwe contains several spatial components, the most prominent being the sandstone hill itself, with a flat summit 30m high and 300 m long, with vertical cliffs that can only be accessed through specific routes. The hill is surrounded by a flat valley that includes discrete spatial areas, a few of which are enclosed with low stone walling.5

Mapungubwe's spatial organization continued to evolve into a new elite pattern that included a stonewalled enclosure which provided ritual seclusion for the king. Other stonewalling demarcated entrances to elite areas, noble housing, and boundaries of the town centre. The hilltop became a restricted elite area with lower-status followers occupying the surrounding valley and neighboring settlements, thus emphasizing the spatial and ritual seclusion of the leader and signifying their sacred leadership.6

Mapungubwe Hill, the treeless area in front housed commoners. photo by Roger de la Harpe.

terrace stone walls at Mapungubwe, photos by L Fouché.

collapsed stone walls in the Mapungubwe area, ca. 1928, Frobenius Institute. It should be noted that the site was known before the more famous ‘discovery’ by L. Fouché in 19337.

Mapungubwe had grown to a large capital of about 10 ha, inhabited by a population of around 2-5000 people, sustained by floodplain agriculture of mixed cereals (millet and sorghum) and pastoralism. Comparing its settlement size and hierarchy to the capitals of historically known kingdoms, such as the Zulu, suggests that Mapungubwe probably controlled about 30,000 km2 of territory, about the same as the Zulu kingdom in the early 19th century.8

There are a number of outlying settlements with Mapungubwe pottery in the Limpopo area which however lack prestige walling and instead occupy open situations. Those that have been investigated, such as Mutamba, Vhunyela, Skutwater and Princes Hill were organized according to the Central Cattle Pattern, indicating that they were mostly inhabited by commoners. However, the recovery of over 187 spindle whorls from Mutamba, about 80 km southeast of Mapungubwe, indicates that textile manufacture and trade weren’t restricted to elite settlements.9

Map showing some of the ruins contemporary with Mapungubwe.10

Gold mining and trade before and during the age of Mapungubwe.

Wealth from local tributes and long-distance trade likely contributed to the increase in political power of the Mapungubwe rulers. The material culture recovered from the capital and other outlying settlements, which includes Chinese celadon shards, dozens of spindle-whorls for spinning cotton textiles, and thousands of glass beads, point to the integration of Mapungubwe into the wider trade network of the Indian Ocean world via East Africa's Swahili coast.11

Prior to the rise of Mapungubwe, the 9th-10th century site of Schroda was the first settlement in the interior to yield a large number of ivory objects and exotic glass beads, indicating a marked increase in long-distance trade from the Swahili coast, whose traders had established a coastal entrepot at Sofala to export gold from the region. These patterns of external trade continued during the K2 period when local craftsmen produced their own glass beads by reworking imported ones and then selling their local beads to other regional capitals.12

It is the surplus wealth from this trade, and its associated multicultural interaction, that presented new opportunities to people in the Mapungubwe landscape. A marked increase in international demand contributed to an upsurge in gold production that began in the 13th century and is paralleled by an economic boom at the Swahili city of Kilwa on the East African coast. The distribution of Mapungubwe pottery in ancient workings and mines such as at Aboyne (1170 CE ± 95) and Geelong (1230CE ± 80) in southern Zimbabwe, indicates that the Mapungubwe kingdom may have expanded north to control some of the gold fields.13

A large cache of gold artifacts was found in the royal cemetery of Mapungubwe, dated to the second half of the 13th century. The grave goods included a golden rhino, bowl, scepter, a gold headdress, gold anklets and bracelets, 100 gold anklets and 12,000 gold beads, and 26,000 glass beads. Radiocarbon dates indicate that the gold objects were all made in the early 13th century, at the height of the town’s occupation.14

Analysis of the gold objects suggests that they were manufactured locally. Metal was beaten into sheets of the required thickness and then cut into narrow strips, or the strips were made from wire that was hammered and smoothed using an abrasive technique. The strips were then wound around plant fibers to form either beads or helical structures for anklets and bracelets, or around a wooden core for the rhino and bovine figurines.15

golden rhinoceros, bovine and feline figures, scepter, headdress, and gold jewelry from Mapungubwe, University of Pretoria Museums, Museum of Gems and Jewellery, Cape Town.

Its however important to emphasize that long-distance trade in gold from Mapungubwe and similar ‘Zimbabwe culture’ sites (the collective name for the stone ruins of southern Africa) was only the culmination of processes generated within traditional economies and internal political structures that were able to exploit external trade as one component of emergent hierarchical formations already supervising regional resources on a large scale.16

The trade of gold in particular appears to have also been driven by internal demand for ornamentation by elites, alongside other valued items like cattle, copper and iron objects, glass beads, and the countless ostrich eggshell beads found at Mapungubwe and similar sites that appear to have been exclusively acquired through trade with neighboring settlements.17

Gold has been recovered from numerous 'Zimbabwe culture' sites, but few of these have been excavated professionally by archaeologists and subjected to scientific analysis, with the exception of Mapungubwe and the site of Thulamela (explored below). Incidentally, Gold fingerprinting analysis shows that the Thulamela gold and part of the Mapungubwe collection came from the same source, indicating that miners from Mapungubwe exploited it before miners from Thulamela took it over.18

Around 1300 CE, the valley and hilltop of Mapungubwe were abandoned, and the kingdom vanished after a relatively brief period of 80 years. The reasons for its decline remain unclear but are likely an interplay of socio-political and environmental factors.

In most of the ‘Zimbabwe culture’ societies, sacred leadership was linked to agricultural productivity, rainmaking, ancestral belief systems, and a ‘high God’, all of which served to confirm the legitimacy of a King/royal lineage. Climatic changes and the resulting agricultural failure would have undermined the legitimacy of the rulers and their diviners while emboldening rival claimants to accumulate more followers and shift the capital of the kingdom.19

It’s likely that the sections of Mapungubwe’s population shifted to other settlements that dotted the region, since Mapungubwe-derived ceramics have been found in association with a stonewalled palace in the saddle of Lose Hill of Botswana20. Others may have moved east towards the town of Thulamela whose earliest occupation dates to the period of Mapungubwe’s ascendancy, and whose elites derived their gold from the same mines as the rulers of Mapungubwe.

The ruined town of Thulamela from the 13th to the 17th century.

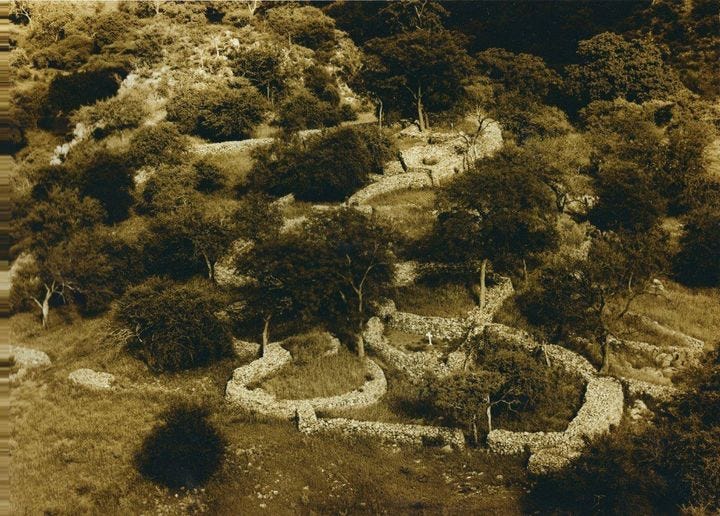

Thulamela is a 9-hectare site about 200km east of Mapungubwe. It consists of several stone-walled complexes and enclosures on the hilltop overlooking the Luvuvhu River which forms a branch of the Limpopo River. The stone-walled enclosures cluster according to rank in size and position, with the majority being grouped around a central court area situated at the highest and most isolated part of the site. The status of the inhabitants is reflected in the volume of stone used, all of which are inturn surrounded by non-walled areas of habitation in the adjacent valley.21

Archeological evidence from the site indicates that a stratified community lived at Thulamela, with elites likely residing on the top of the hill while the rest of the populace occupied the adjacent areas below. A main access route intersects the central area of the hill complex leading to an assembly area, which in turn leads to a private access staircase to the court area. construction features including stone monoliths, small platforms, and intricate wall designs are similar to those found in other ‘Zimbabwe culture’ sites likely denoting specific spaces for titled figures or activities.22

Thulamela ruins, aerial view.

The site has seen three distinct periods of occupation, with phase I beginning in the 13th century, Phase II lasting from the 14th to mid-15th century, and Phase III lasting upto the 17th century. The earliest settlements had no stone walling but there were finds of ostrich eggshell beads similar to those from Mapungubwe. Stone-walled construction appeared in the second phase, as well as long-distance trade goods such as glass beads, ivory, and gold.23

Occupation of the site peaked in the last phase, with extensive evidence of metal smithing of iron, copper, and gold, Khami-type pottery (from the Torwa kingdom capital in Zimbabwe), and a double-gong associated with royal lineages. Other finds included Chinese porcelain from the late 17th/early 18th century associated with the Rozvi kingdom capital of DhloDhlo in Zimbabwe, spindle-whorls for spinning cotton, ivory bangles, and iron slag from metal production.24

Two graves were discovered at the site, with one dated to 1497, containing a woman buried with a gold bracelet and 290 gold beads, while the other was a male with gold bracelets, gold beads, and iron bracelets with gold staple, dated to 1434. The location of the graves and the grave goods they contained indicate that the individuals buried were elites of high rank at Thulamela, and further emphasize the site's similarity with other ‘Zimbabwe culture’ sites like Mapungubwe.25

The recovery of other gold beads, nodules, wire, and fragments of helically wound wire bangles, along with several fragments of local pottery with adhering lumps of glassy slag with entrapped droplets of gold, provided direct evidence of gold working in the hilltop settlement. The fabrication technology employed in Thulamela's metalworking was similar to that found at Mapungubwe.26

Thulamela ruins, photos by Chris Dunbar

Gold bracelets, iron and gold bangles, and ostrich eggshell beads from Thulamela.

Thulamela and the kingdoms of Khami and Rozvi during the 15th to 17th century.

The presence of gold and iron grave goods, along with Chinese porcelain and glass from the Indian Ocean world indicates that trade and metallurgy were salient factors in urbanization, social structuring, and state formation across the region. The site of Thulamela was the largest in a cluster of three settlements near the Luvuvhu River, the other two being Makahane and Matjigwili. The three sites exhibit similar features including extensive stone walling and stone-built enclosures, and the division of the settlement into residential areas.

Archeological surveys identified the central court area of Makahane on the hilltop, enclosed in a U-shaped wall, with the slopes being occupied by commoners. A gold globule found at Makahane indicates that it was also a gold smelting site. The site is traditionally thought to have been occupied in the 17th-18th centuries according to accounts by the adjacent communities of the Lembethu, a Venda-speaking group who still visited the site in the mid-20th century to offer sacrifices and pray at the graves of the kings buried there.27

The sites of Thulamela and Makahane occupy an important historical period in south-eastern Africa marked by the expansion of the kingdoms of Torwa at Khami and the Rozvi state at DhloDhlo in Zimbabwe, whose material culture and historical traditions intersect with those of the sites. It’s likely that the two sites represent the southernmost extension of the Torwa and Rozvi traditions (similar to the ruined stone-towns of eastern Botswana), without necessarily implying direct political control28.

The Rozvi kingdom is said to have split near the close of the 17th century after the death of its founder Changamire Dombo who had in the 1680s expelled the Portuguese from the kingdom of Mutapa after a series of battles. According to Rozvi traditions, some of the rival claimants to Changamire’s throne chose to migrate with their followers into outlying regions, with one moving the the Hwange region of Zimbabwe, while another moved south and crossed the Limpopo river to establish the kingdom of Thovhela among the Venda-speakers with its capital at Dzata, which appears in external accounts from 1730.29

Besides Thulamela and Makahane, there are similar ruins in the Limpopo region with material culture associated with both the Torwa and Rozvi periods. The largest of these is the site of Machemma, which is located a few dozen kilometers south of Mapungubwe. It was a large stone-walled site with highly decorated walls, whose court area yielded Khami band-and-panel ware, ivory, gold ornaments, and imported 15th-century Chinese blue-on-white porcelain.30

section of the ruins of Machemma and Makahane Ruins, photos by Chris Dunbar, ACT Heritage.

Outline of the Makahane ruins, by T. Huffman.

A brief social history of south-east Africa and the transition from Thulamela to Dzata.

The fact that both Thulamela and Makahane were well known in local tradition indicates their relatively recent occupation compared to Mapungubwe and other early ‘Zimbabwe culture’ sites which were abandoned many centuries prior.

The construction of the ‘Zimbabwe culture’ sites is attributed to the Shona-speaking groups of south-eastern Africa.31 The site of Makahane is however associated with the Nyai branch of the Lembethu, a Venda-speaking group. Venda is a language isolate that shows lexical similarities with the Shona language, which linguists and historians mostly attribute to the southern expansion of an elite lineage group known as the Singo from Zimbabwe during the 18th century.32 Although it should be noted that the Singo would have encountered pre-existing groups that likely included other Venda speakers indicating that the Shona elements in the Venda language were acquired much earlier than this.33

Venda traditions on the southern migration of the Singo describe the latter’s conquest of pre-existing societies to establish a vast state centered at the site of Dzata, which later collapsed in the mid-18th century. They identify the first Singo rulers as Ndyambeu and Mambo, who are both associated with the Rozvi kingdom (Mambo is itself a Rozvi aristocratic title). It’s likely that the traditions of the Singo’s southern migration and conquest of pre-existing clans refer to this expansion associated with the split between Changamire's sons after his demise.34

The same traditions mention that when the Singo emigrated from south-central Zimbabwe, they first settled in the Nzhelele Valley and established themselves at Dzata. The latter was a stone-walled settlement that was initially equal in size to the pre-existing capitals of the Lembethu at Makahane Ruin, and the Mbedzi at the Tshaluvhimbi Ruin, before the Singo rulers expanded their kingdom and attracted a larger following by the turn of the 18th century.

The Singo kingdom of Dzata in the 18th century.

Dzata is a 50-hectare settlement located on the northern side of the Nzhelele River, a branch of the Limpopo River. The core of the settled area is a cluster of neatly coursed low-lying stone walls, with a court area about 4,500 sqm large, surrounded by a huge ring of surface scatters with some rough terraced walling. Dzata is the only level-5 ‘Zimbabwe culture’ site south of the Limpopo River, indicating it was the center of a large kingdom with a population equal to that found at Khami and Great Zimbabwe.35

A Dutch account obtained from a Tsonga traveler Mahumane, who was visiting the Delagoa Bay in 1730, mentions the dark blue stone walls of Dzata, in the kingdom, called ‘Thovhela’ (possibly a title or name of a king), where he had been a few years earlier. The account identifies the capital as ‘Insatti’ (a translation of Dzata) which was "wholly built with dark blue stones —the residences as well as a kind of wall which encloses the whole", adding that "The place where the chief sits is raised and also [made] from the mentioned kind of stone..."36

the ruins of Dzata, with low-lying walls of dark-blue stones. photos by Musa Matchume, Faith Dowelani.

Ethnohistoric Information from other Venda sites indicates that the central cluster of stone walls at Dzata demarcated the royal area, whereas the big surrounding ring housed the commoners. According to some traditions, Dzata experienced more than one construction phase, associated with two kings. The town grew during the reign of Dimbanyika, the fourth king at Dzata, after he had finished consolidating his authority over the Venda. It was later expanded by King Masindi after the death of King Dimbanyika.37

Changes in the styles of walling and other features likely reflected political shifts at Dzata. The settlement was intersected by a central road through the commoner area to the stone walled royal section, which was separated by cattle byres. On the opposite side of the byres was the assembly area with a small circular platform and stone monoliths. Excavations of this area yielded four radiocarbon dates, all calibrated to around 1700 CE,38 while other sites near and around Dzata provided multiple dates ranging from the 16th century to the early 19th century.39

The material culture recovered from Dzata includes iron weapons and tools, coiled copper wire interlaced with small copper beads, spindle whorls, ivory fragments, bone pendants, and blue glass beads. The numerous remains of iron furnaces and copper mines in its hinterland corroborate 18th-century accounts of intensive metal working and trading from the region, which was controlled by the ruler of Dzata. Gold, copper, and ivory from Dzata were exported to the East African coast through Delagoa Bay, where a lucrative trade was conducted with the hinterland societies.40

Trade between Dzata and the coast declined drastically around 1750, around the time when the Singo Venda abandoned Dzata. Following the collapse of the Singo kingdom, other stone-walled sites were built across the region, with interlocking enclosures separating elite and commoner areas41. Limited trade between the coast and the Limpopo region continued, as indicated by an account from 1836, mentioning trade routes and mining activities in the region, as well as competition between Venda rulers for access to trade goods.42

By the mid-19th century, however, the construction of stone-walled towns had ceased, after social and political changes associated with the kingdoms of the so-called mfecane period43.

The old ruins of Thulamela, Makahane, and Dzata nevertheless retained their significance in local histories as important sites of veneration, or in the case of Dzata, as the capital of a once great kingdom that is still visited for annual dedication ceremonies called Thevhula (thanksgiving).

Thulamela.

Traditional African religions often co-existed with “foreign” religions for much of African history, including in places such as the kingdom of Kongo, which was considered a Christian state in the 16th century but was also home to a powerful traditional religious society known as Kimpasi.

Please subscribe to read about the history of the Kimpasi religious society of Kongo on our Patreon:

Map by Shadreck Chirikure et al, from “No Big Brother Here: Heterarchy, Shona Political Succession and the Relationship between Great Zimbabwe and Khami, Southern Africa.”

Mapungubwe and the Origins of the Zimbabwe Culture by Thomas N. Huffman pg 15-17)

Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe: The Origin and Spread of social complexity in Southern Africa by Thomas N. Huffman pg 42)

Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe: The Origin and Spread of social complexity in Southern Africa by Thomas N. Huffman

Shell disc beads and the development of class‑based society at the K2‑Mapungubwe settlement complex (South Africa) by Michelle Mouton pg 3-4)

Shell disc beads and the development of class‑based society at the K2‑Mapungubwe settlement complex (South Africa) by Michelle Mouton pg 5)

The lottering connection: revisiting the 'discovery' of Mapungubwe. by by Justine Wintjes and Sian Tiley-Nel.

Mapungubwe and the Origins of the Zimbabwe Culture by Thomas N. Huffman pg 25-26, Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe: The Origin and Spread of social complexity in Southern Africa by Thomas N. Huffman pg 44, )

Mapungubwe and the Origins of the Zimbabwe Culture by Thomas N. Huffman pg 22, Fiber Spinning During the Mapungubwe Period of Southern Africa: Regional Specialism in the Hinterland by Alexander Antonite pg 106)

Fiber Spinning During the Mapungubwe Period of Southern Africa: Regional Specialism in the Hinterland by Alexander Antonites

Fiber Spinning During the Mapungubwe Period of Southern Africa: Regional Specialism in the Hinterland by Alexander Antonite pg 110-115, Mapungubwe and the Origins of the Zimbabwe Culture by Thomas N. Huffman pg 21

Mapungubwe and the Origins of the Zimbabwe Culture by Thomas N. Huffman pg 19-20)

Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe: The Origin and Spread of social complexity in Southern Africa by Thomas N. Huffman pg 50, Ungendering Civilization edited by K. Anne Pyburn pg 63.

Dating the Mapungubwe Hill Gold by Stephan Woodborne

Dating the Mapungubwe Hill Gold by Stephan Woodborne et al.

The Zimbabwe Culture: Origins and Decline of Southern Zambezian States by Innocent Pikirayi pg 21)

Shell disc beads and the development of class‑based society at the K2‑Mapungubwe settlement complex (South Africa) by Michelle Mouton pg 16-17

Trace-element study of gold from southern African archaeological sites by D. Miller et al.

Mapungubwe and the Origins of the Zimbabwe Culture by Thomas N. Huffman pg 15, Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe: The Origin and Spread of social complexity in Southern Africa by Thomas N. Huffman pg 51)

Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe: The Origin and Spread of social complexity in Southern Africa by Thomas N. Huffman pg 51)

Late Iron Age Gold Burials from Thulamela (Pafuri Region, Kruger National Park by Maryna Steyn pg 74)

A preliminary report on settlement layout and gold melting at Thula Mela by M.M Kusel pg 58-60)

Late Iron Age Gold Burials from Thulamela (Pafuri Region, Kruger National Park by Maryna Steyn pg 75-76,

A preliminary report on settlement layout and gold melting at Thula Mela by M.M Kusel pg 60-61)

Late Iron Age Gold Burials from Thulamela (Pafuri Region, Kruger National Park by Maryna Steyn pg 76-84)

Trace-element study of gold from southern African archaeological sites by D. Miller et al. pg 298, The fabrication technology of southern African archeological gold by Duncan Miller and Nirdev Desai

Settlement hierarchies Northern Transvaal by T. Huffman, pg 16-17, A preliminary report on settlement layout and gold melting at Thula Mela by M.M Kusel pg 56, 63)

A preliminary report on settlement layout and gold melting at Thula Mela by M.M Kusel pg 63

The Zimbabwe Culture by Innocent Pikirayi pg 215

Settlement hierarchies Northern Transvaal by T. Huffman pg 14-15)

Snakes & Crocodiles : Power and Symbolism in Ancient Zimbabwe by Thomas N. Huffman pg 1-5, The Zimbabwe Culture: Origins and Decline of Southern Zambezian States by Innocent Pikirayi pg 15-18

Language in South Africa edited by Rajend Mesthrie pg 71-72, Language and Social History: Studies in South African Sociolinguistics edited by Rajend Mesthrie pg 45-46)

Settlement hierarchies Northern Transvaal by T. Huffman pg 23, The Ethnoarchaeology of Venda-speakers in Southern Africa by J. H.N Loubser pg 398-399.

Settlement hierarchies Northern Transvaal by T. Huffman pg 21-22, The Ethnoarchaeology of Venda-speakers in Southern Africa by J. H.N Loubser pg 391

Settlement hierarchies Northern Transvaal by T. Huffman pg 19)

The Ethnoarchaeology of Venda-speakers in Southern Africa by J. H.N Loubser pg 293, Settlement hierarchies Northern Transvaal by T. Huffman pg 21.

Settlement hierarchies Northern Transvaal by T. Huffman pg 19)

The model of Dzata at the National Museum by J. H.N Loubser pg 24

The Ethnoarchaeology of Venda-speakers in Southern Africa by J. H.N Loubser pg 290, 307-308.

The model of Dzata at the National Museum by J. H.N Loubser pg 25

The Archaeology of Southern Africa By Peter Mitchell pg 340

The model of Dzata at the National Museum by J. H.N Loubser pg 25

The Archaeology of Southern Africa By Peter Mitchell pg 340-341.

Always great to wake up on a Monday morning in Japan and open my mail box, something good is bound to come out of it, one more thing I'd like to add, seemed like long distance trade was taking place between far away West Africa and Thulamela, perhaps indirectly but if they were reaching the Kingdom of the Kongo, I don't see why not.

https://africawild-forum.com/viewtopic.php?t=1899

Great article!