A history of currencies and monetary systems in the southern half of Africa

African monetary systems were characterized by the concurrent use of classical (metal) currencies and commodity currencies that fulfilled a variety of functions.

Many societies in the southern half of the continent developed diverse types of monetary systems using different currency objects that circulated and held value in multiple contexts.

In these pre-colonial economies, African coins, cowries, gold dust, luxury cloth, and copper crosses acted as repositories of value in certain contexts, media of exchange in others, and objects of use or display at other times.

Documentary and archaeological evidence shows that African societies managed multiple forms of money between different currency zones in regional exchanges that extended beyond the continent. The expansion of currency use linked distant economies where these monies originated, such as the copper-producing regions of Katanga, the Gold-producing regions of Zimbabwe, and the ‘Textile Belt’ of central Africa.

This article explores the history of currencies in the southern half of Africa and provides an overview of the monetary systems found across the region.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The currencies of West-Central Africa

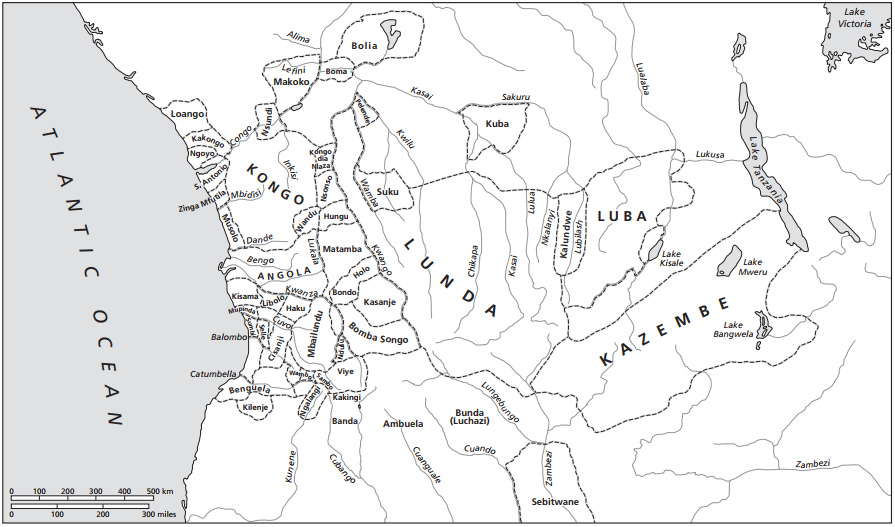

Map of west-central Africa, ca. 1850 by J. K. Thornton

Early descriptions of the kingdom of Kongo mention that traders used a general-purpose money, in the form of seashells called nzimbu, which the first Portuguese visitors in 1491 received from government officials to cover their expenses in traveling from the coast to the capital.1

These shells were obtained from the island of Luanda, which was already under the control of the ManiKongo (king of Kongo) by 1506, when it was first described by the chronicler Duarte Pacheco Pereira:

“They [the islands of Luanda] are very near the mainland, and the Africans who inhabit them belong to the lordship of Maniconguo, the Conguo country extending even beyond them. The Africans of these islands pick up small shells (of the size of pine-nuts in their shell) which they call “zinbos.” These are used as money in the country of Maniconguo [ManiKongo] ; fifty of them will buy a hen, and three hundred a goat and so forth; and when Maniconguo wishes to confer a favour on one of his nobles or reward a service done to him, he orders him to be given a certain number of these “zinbos,” just as our princes bestow money of these realms on those who deserve it, and often on those who do not.”2

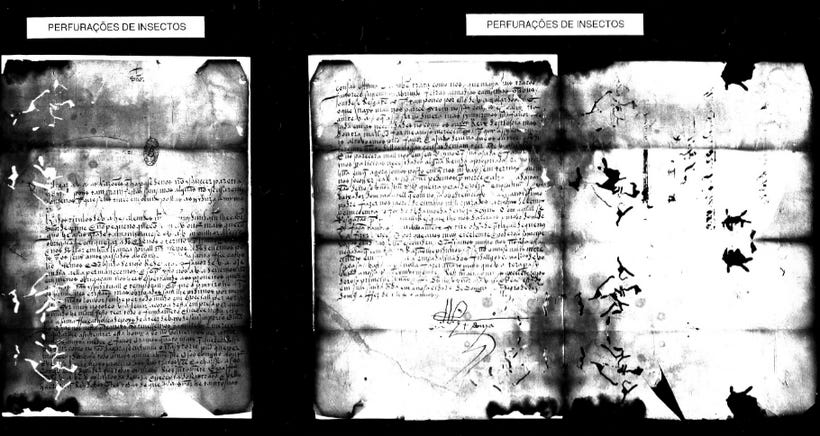

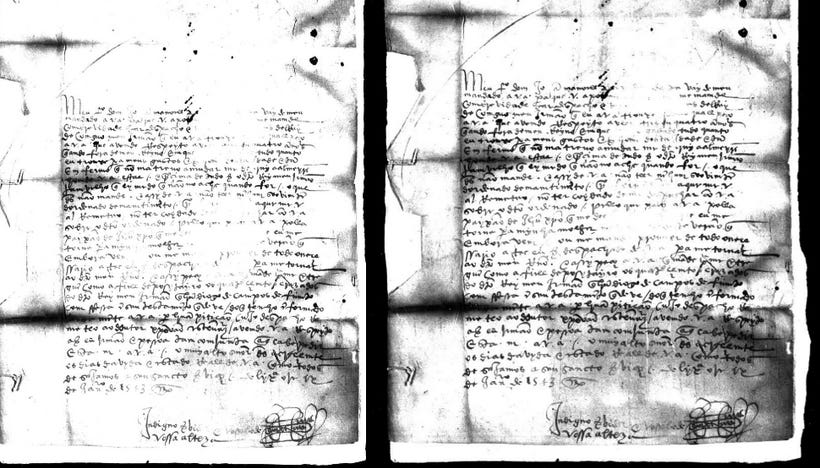

In its export trade, the kingdom utilised a rather complex system of currency exchanges and credits when converting its currency values to European silver units. The nature of this working arrangement can be gleaned from a “letter of credit” which Afonso I drew up for his brother Manuel, who was travelling to Rome as his ambassador in 1540.

Afonso asked for a grant of 5,000 cruzados (Portuguese silver currency), and in exchange created a credit of 150 kofu of nzimbu in Kongo. Other such money matters in the mid-16th century were handled by the Kongolese factor in the city of Lisbon, who for some fifteen years was Antonio Vereira, a noble Kongolese resident there.3

Cowrie shell currency was measured in standard containers holding 40, 100, 250, 400, or 500 shells. Beyond these, the measure that consisted of containers amounting to 1000 shells was called a funda, 10,000 was a lufuku, while a Kofu consisted of 20,000 cowrie shells.4 Exchange rates with Portuguese silver units in 1575 gave the following conversions: 1 funda was worth 100 réis, 1 lufuku corresponded to around 1000 réis, and 1 kofu to 2000 réis, or 5 cruzados.5

Letter from King Afonso of Kongo, requesting a credit exchange to fund D. Manuel, his ambassador, for the latter’s trip to Rome. 1540. Arquivo Nacional Torre do Tombo, Portugal. PT/TT/CC/1/68/92.

Letter by D. Manuel, ambassador of Kongo, requesting 400 cruzados belonging to King Afonso. 1543. Arquivo Nacional Torre do Tombo, Portugal. PT/TT/CC/1/73/41.

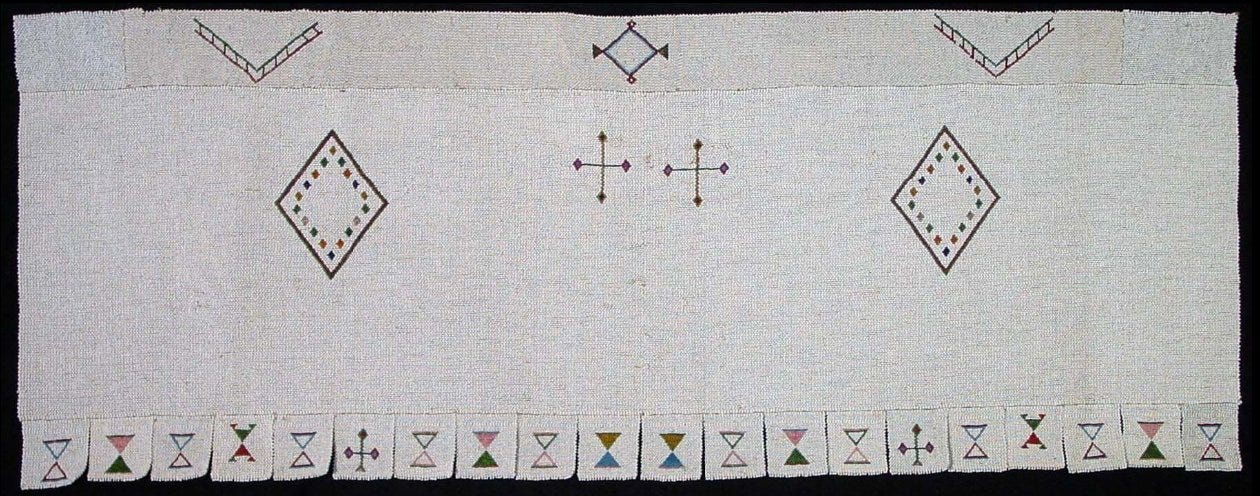

Another pre-existing currency in West-Central Africa was cloth made from threads of palm, whose production and trade were ubiquitous across the ‘Great textile belt’ of Central Africa, from Angola to Zambia. The standard size of a woven piece of cloth ranged from 40x40 cm to 52x52 cm, with luxury cloth measuring 67x67cm. These were sewn together to form strips of equal length that were joined together for a waist-cloth.6

These luxury cloths, which were often favourably compared to Italian velvet, were first described in Kongo during the 16th century. They appear as currencies in both Kongo and the northern kingdom of Loango during the early 17th century, when large quantities were imported into the Portuguese coastal colony of Angola to pay soldiers and for re-export further inland. Some of this cloth originated as far inland as the Kuba kingdom.

Like all currencies, the luxury cloth’s general acceptability and multiple fuctions kept it in constant demand. Its value was also measured against the nzimbu shells and the Portuguese reis (a unit of silver), with the best cloths priced at 640 reis a piece (about 1.7 cruzados). Over 100,000 meters of these were exported from Kongo during those two years alone.7

The cloth could be packaged into different units of four, ten, twenty, forty, or a hundred. A unit of account called a mukuta, which consisted of ten cloths wrapped or sewn together, was commonly found along the entire coast. Some traders stamped the cloth to create new denominations, called makutas, that were worth 100 reis in Angola.8

Kuba textiles at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

Kongo luxury cloth: cushion cover, 17th-18th century, Polo Museale del Lazio, Museo Preistorico Etnografico Luigi Pigorini Roma

The Textile belt of West-Central Africa. Map by J. Thornton

When the Portuguese assisted the Kongo monarch Álvaro to drive off the Jaga invaders in the 1570s, the king gave them the right to collect some revenue from the “mines” of nzimbu shells on Luanda Island for a period of time. As Portuguese presence in Luanda increased, they began to extort revenue from the mines and import shells from the Indian Ocean.

The effect of the Portuguese’s partial control of the nzimbu supply has been suggested by some scholars to have resulted in a devaluation of the currency against European silver currencies, based on the declining price of Kongo’s exports during the 1620s.9 However, other scholars maintain that the internal value for the nzimbu shells was unaffected, as the currency remained in circulation long after this, being used for paying taxes, in most market transactions, and even by the Portuguese for paying soldiers during the wars of the 1670s.10

Additionally, by the late 17th century, the Portuguese had adopted the expedient of using monetary cloth of Loango and libongo. But supplies were limited since trade with the eastern provinces of Kongo declined. This prompted the Portuguese to mint copper coins in Luanda in 1694. However, the coins were quickly removed from circulation after failing to turn a profit, forcing the Portuguese to revert to the cloth currencies.11

A report from 1769 noted that the ordinary money in the Portuguese coastal colony of Angola was cloth from Kongo and nzimbu shells, adding that it was used by the Portuguese authorities just like they would “customarily use money of gold, silver or copper.” As late as the early 20th century, prestige cloth and nzimbu shells would remain the main currencies used in west-central Africa, before they were replaced by coins well into the colonial era.12

17th century illustration showing textile trading in the north Kwanza region (Ndongo kingdom), by Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi.

Currencies of Central and Southern Africa

In South-East Africa during the 16th century, the main currencies were gold dust and a local cotton cloth known as Machira, which were used for larger transactions. smaller transactions were carried out using copper bars, tin-alloy coins/bars, and glass/clay beads that could be exchanged for the Portuguese cruzado.

According to the account of the friar João dos Santos, who visited the region in the late 16th century:

“The smallest money used in these lands is a weight of gold called a tanga, which is worth three vintens, and the largest is a matical [mithqal] worth four hundred and eighty reis. There is also another kind of money which is used for buying small articles. This is little copper bars about half a span in length and two fingers wide, which they call macontas ; each of these is also worth three vintens.

There is also current a coin made of pewter [tin-alloy], which they call calaim : it is made in bars, each weighing half a pound. They call these bars pondos, and each of these pondos is worth two tangas, that is six vintens. In these lands small earthenware beads glazed and coloured are also current as ordinary money. They are threaded on strings of about a span in length. These strings of beads are called maties, ten mites joined together are called a lipoto, and twenty lipotes joined together are called motava which is usually worth one cruzado.

Besides these moneys, all kinds of things are bought and sold for any sort of cloth, with which debts are paid instead of with gold… At the trading fair a motava will reach forty cruzados and they sell straightaway all things that they carry there, earning twice as much or even more, as their original price.”13

All of the currencies and measurements mentioned in this 16th-century account appear in the material and textural record of different societies in the region, extending from south-east Africa to the Great Lakes.

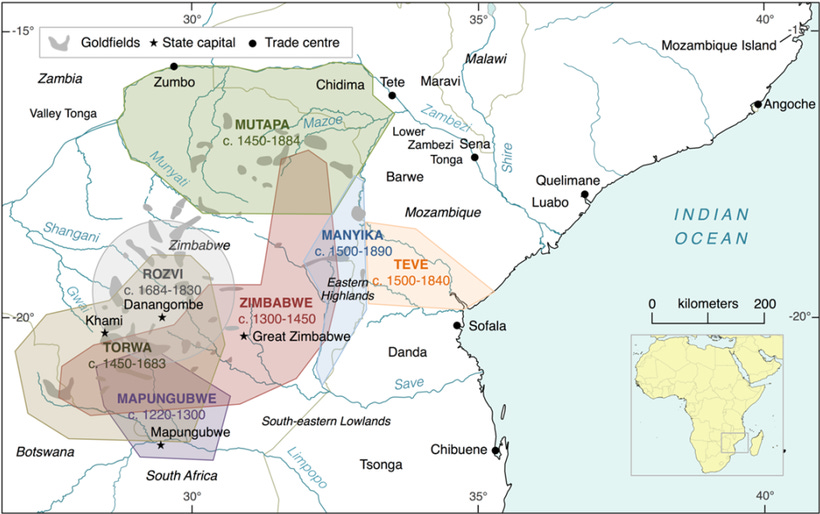

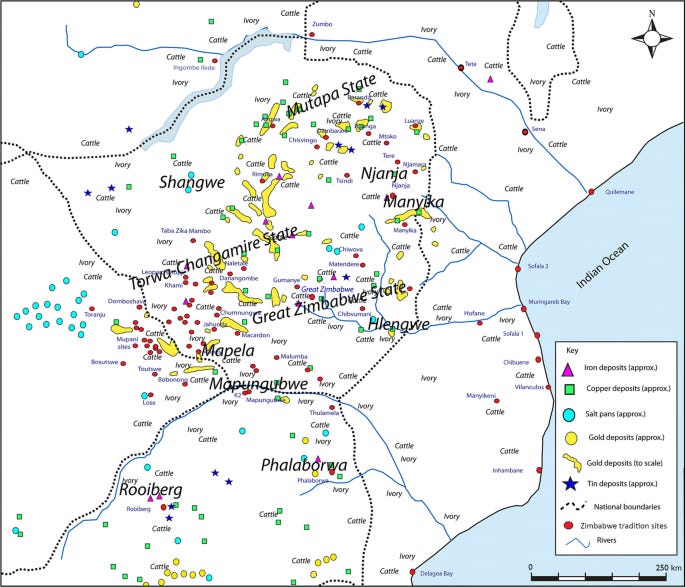

Map showing some of the kingdoms of south-east Africa

Gold was a major export from South-East Africa to the Indian Ocean world since the 10th century, as described in al-Masudi’s account of the ‘land of Sofala’. Early Portuguese estimates from 1502 and 1506 indicate that between 1.35 to 2 million mithqals (maticals) of gold were exported a year from South-East Africa via the coast of Sofala.

More than 4,000 pre‐colonial gold workings are known from Zimbabwe alone, and over 2,000 from eastern Botswana. Most important are the finds of gold crucibles at the ruins of Khami, Great Zimbabwe, and Thulamela, which provide direct evidence for gold processing. Besides these were the discoveries of cup-shaped depressions in eastern Botswana, which offer evidence for gold milling, often located near ancient ruins such as Vukwe and Domboshaba.14

Archaeological finds from Great Zimbabwe and similar stone ruins in South Africa, Botswana, Mozambique, and Zambia have uncovered gold objects, copper currency crosses, as well as a 14th-century copper coin from Kilwa (located 2,500 km north in Tanzania), and a 15th-century tin ingot from Rooiberg (located 500 km south in Limpopo, South Africa).15

Additionally, three coins and a chain ornament dated to the 11th/12th century, which were cast using copper from the Katanga Copperbelt, were found in the coastal settlement of Ibo in the Quirimbas Archipelago of Mozambique.16 These finds point to the pre-existing use of metal currencies in south-eastern Africa prior to their first appearance in the documentary record.

Gold objects from different ‘Zimbabwe tradition sites’: (first image) golden rhinoceros (A) and gold anklet coils (B) from Mapungubwe, South Africa. ca 13th century17; (second image) gold beads and gold wire armlet, ca. 14th-15th century, Ingombe Ilede, Zambia.18 (last image) Gold and carnelian beads from Ibo in the Quirimbas islands, Mozambique. ca. 10th-12th century CE. Archeometallurgical analysis showed a remarkable similarity between the gold bead of Ibo and the ones found at Mapungubwe19

Gold melting crucibles from the Fireguard Midden, Great Zimbabwe. photo by Shadreck Chirikure.

(top left) 14th-century copper coin from found at Great Zimbabwe, image by T. Huffman. (bottom) copper coins from Kilwa at the Tanzania museum. (right) 11th/12th-century Coins found at Ibo, Mozambique.

The approximate distribution of sources of ore and other resources within the territory of the Great Zimbabwe state. Map by Shadreck Chirikure.

The museum of Bulawayo in Zimbabwe contains gold weights and scales obtained from the polity of Mangwende (17th-19th century), formerly a part of the Mutapa kingdom in North-eastern Zimbabwe.

These weights were known in the Shona language as mairi (two), mana (four), mashanu (five), nyabadza (price of a hoe), nyarusimba (price of a piece of iron), and a tanga, which was about an eighth of a mithqal. The tanga, whose value was set against the gold mithqal, appears to have been the more common unit of measurement for large transactions.20

It’s instructive to note that 18th-century Portuguese accounts of transactions in the estates (prazos) from the Rivers region of Mozambique mostly used the gold mithqal (matical) and the tanga as the unit of value, rather than their own silver units (reis), due to the scarcity of the silver coins (cruzados). 1 matical was worth 8 cruzados 21

Cotton textiles were both an item of trade and a form of currency, as described in the same 16th-century Portuguese account:

“The land is most difficult to conquer, as we experienced ourselves, and the more people are sent the less it may be conquered and provided for, and few people can do nothing except in the way of trade; which trade is considerable, particulary the machiras one.

Above Sena, there is plenty of cotton, wherewith the dwellers thereof make the spun fabric used in making the machiras in which the province abounds. The beads against which these machiras are traded at Chaul [India] are commonly bought at 50 pardaos a bar, which is four quintals; this bar, placed in Sena with the expenses thereof, may be worth one hundred cruzados… These machiras are sold to the africans on the western bank of the [sena] river, who are called Botongas, at a mitical of gold apiece, which there is the weight of a cruzado and a testoon”22

This local cloth, which was described by 19th-century travellers as “strong and coarse, but clean and white,” was wrapped over the body and crossed over the breast, with some lengths thrown over the shoulder like a cape. Some accounts mention that it was dyed with indigo and other plant dyes, while other accounts mention that it was unbleached. Isolated tax figures suggest that the cost of machira halved in the 17th century, pointing to increased production. The cloth was traded and produced as far as the Limpopo (in modern South Africa), and competed with Indian imports so much as to force the Portuguese to try (but fail) to curtail its production.23

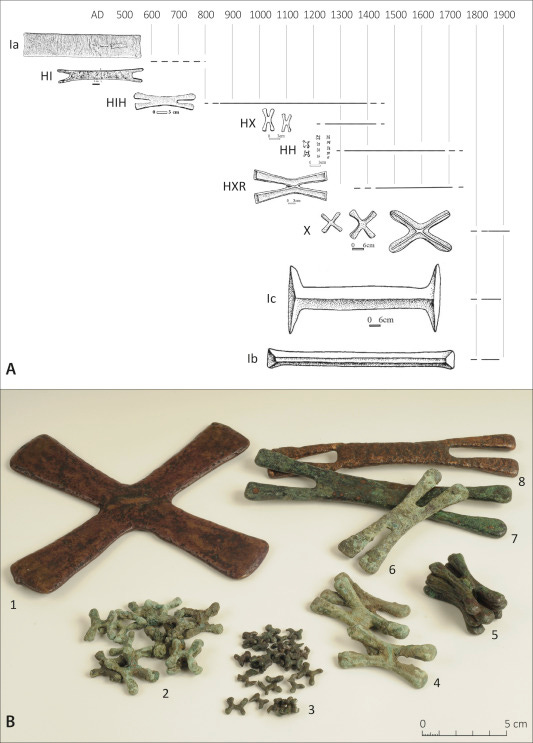

Copper crosses and bars were a more widespread currency system that may have originated in the copper belt of Katanga between the D.R.Congo and Zambia. Copper was produced in this region since the 4th–7th centuries CE and traded over large distances from the 9th to the 19th centuries.24

19th century Copper trade routes in south-central Africa.

Copper was exchanged mainly in the form of cross-shaped ingots, which varied in form and size, likely reflecting the influence of different states in standardizing their currencies.25 Various accounts describing the kingdoms of south-central Africa in the 18th and 19th centuries mention that the copper bars served as currency for large transactions such as taxes, bride wealth, and entry fees to secret societies like the Bambudye of the Luba.

Broad chronology of ingots produced in the Copperbelt between 6th and 19th century CE. Image by N. Nikis.

Miners were paid 3 copper crosses weighing 20kg per trading season while titleholders received about 100kg in tribute, with a total of 115 tonnes of copper circulating in payments and tribute every year. These copper bars were also carried as far as the East African coast, where they were used to import textiles, cowrie shells, and glass beads, which also served as currency.26

There is evidence that some of the Katanga copper was traded as far south as Botswana, where archeometallurgical analysis of copper artefacts found in the Tsodilo Hills was broadly consistent with the Katanga Copperbelt region, rather than the expected Southern African ores.27

Beyond the Limpopo River, copper currencies were obtained from local ores and used in regional trade in pre-colonial societies in the eastern part of South Africa, such as the Xhosa and Zulu kingdoms, which combined copper and iron currencies, with imported brass and glass beads for smaller transactions. These items appear extensively in the region’s archeological record since the late 1st millennium, and would remain in use up to the late 19th century.28

A late 18th-century account of the Lunda province of Kazembe (northern Zambia) indicates that many of the currencies described centuries earlier remained in use across the region.

The account mentions that the main currencies included copper bars and cloth. In particular, cloth had a fixed measurement (called panno/pagne/fathoms, equal to an arm) that was used to express the values of other currencies. Both were used to purchase other items, pay taxes, fees, and labour.

The account also mentions ingots of tin-alloys, which were also called ‘calaim’ as earlier descriptions. Small transactions were made using cowrie shells and glass beads that were imported from the East African coast by the (Tungalagazas) Nyamwezi. Traders also still used units of measurement such as ‘Mutava/Motava’ that were first described in the 16th century.29

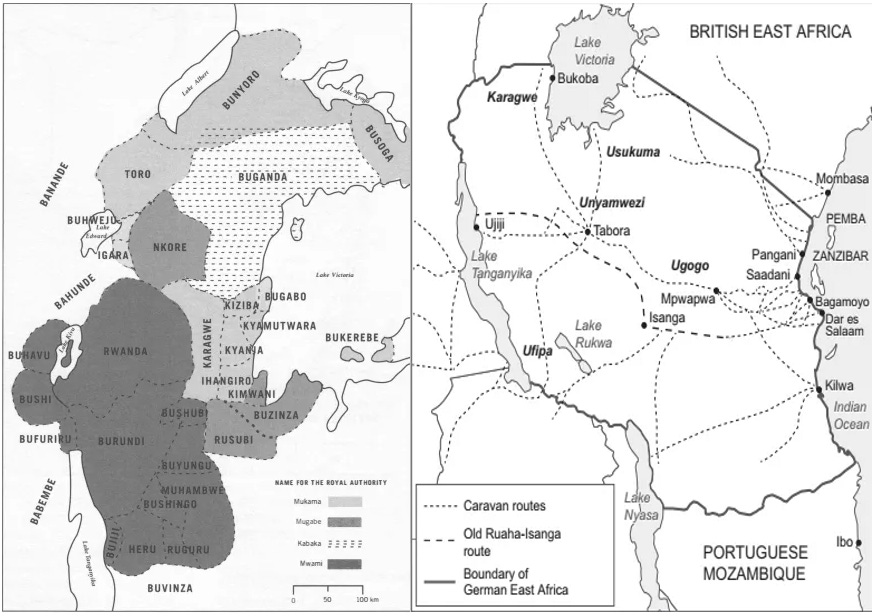

Currencies of the Great Lakes Region.

Cowrie shells and glass beads appear more ubiquitously in the archaeological record of the Great Lakes region, and were already in use as currency when the kingdoms were first described in the 19th century. Cloth, both local and imported, was used in a complementary relationship with cowries and glass beads, typically for larger purchases.

Map of late 19th-century East Africa showing the kingdoms of the Great Lakes and the caravan routes.

Early descriptions of the kingdom of Buganda indicate that the value of virtually every trade item was expressed in terms of cowries (ensimbi ennanda), a hundred of which were tied on a string to form a unit known as the kiasa. Cloth was measured by the ‘dotti’, an imported term, with one dotti being exchanged for about 2,000 cowries. Cowries were used for most transactions and for paying taxes, a practice that continued as late as the early 20th century.30

The use of cowries, cloth, and glass beads across Eastern Africa is widely documented in the 19th century, when a boom in the ivory trade resulted in the expansion of overland trade between the East African coast and the interior regions of Tanzania, Uganda, D.R.Congo, and Malawi.

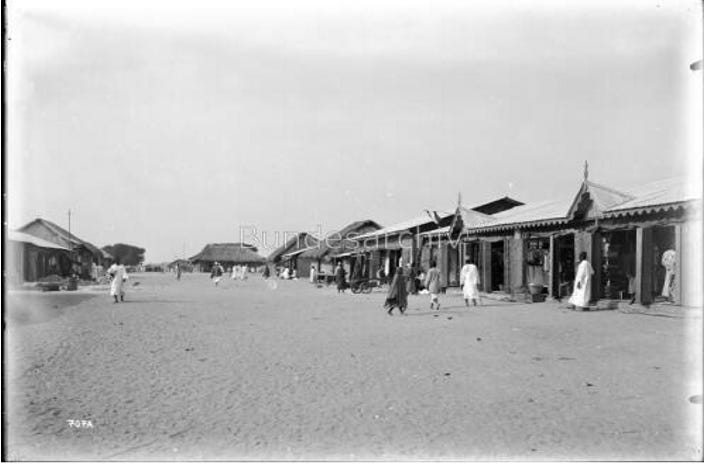

street scene in Tabora, Tanzania. ca. 1906, German federal archives.

While all currencies mentioned above were utilized concurrently, there was an outsized focus on glass beads in the documentary record of European travellers, as they symbolized the archetypal ‘exotic’ currency of the African mainland.31

Contemporary accounts nevertheless stress that cloth was used for most purchases and taxes, while glass beads were used as small change for buying provisions and paying porters —the two expenses that travelers were more concerned with. The 19th-century traveller Joseph Thomson mentions that in the market of Ujiji (Tanzania), “they have made the first advance towards the use of money in the adoption of a bead currency, which performs all the functions of our coppers, cloth being the medium for the larger purchases.”32

The low manufacturing cost of glass beads compared to the high cost of imported ivory initially convinced some European traders who hadn’t reached the interior that Africans were exchanging a high-value commodity for what they derisively called trinkets. However, upon reaching the African markets, they were disappointed to find that ivory had relatively little value in the interior compared to the expensive cloth used to purchase it, and that the glass-bead ‘trinkets’ were only useful as pocket change, and their value was subject to the whims of the African consumers:

“The Birmingham trinkets and knick-knacks, would in East Africa be accepted by women and children as presents, but, unless in exceptional cases, would not procure a pound of grain.”33

Commodities do not always have the same value and meaning in different societies. Just as tons of glass beads were being unloaded on the African coasts, European traders were competing against each other to get ivory, a commodity that for a long time had had little economic value among the societies of the interior, where hunters attimes discarded it or used it as fence posts.34

European traders and travelers continuously complained that each population had its particular preference as to tint, color, and size of glass beads. The choice of the wrong types of glass beads could determine the total failure of an expedition, as happened to Burton and Speke, who had to throw away many glass beads considered worthless, since they couldn’t even be accepted as gifts:

“The various kind of beads [to be carried into the interior] required great time to learn, for the women of Africa are as fastidious in their tastes for beads as the women of New York are for jewelry. The measures also had to be mastered, which, seeing that it was an entirely new business in which I was engaged, were rather complicated, and perplexed me considerably for a time”

Another traveller, Joseph Thomson, also had to dump his cache of beads despite inquiring beforehand: “When we arrived at the lake, we found beads of all kinds ignored, and coloured cloths in demand. The beads we had laboriously transported so far proved utterly useless.”35

The circulation of the glass bead currencies was based on their acceptability, which was in turn derived from their material characteristics, such as their final use as jewellery. The fact that most of the glass beads were circulated by petty traders rather than wealthy merchants, local elites, and kings may account for their rapidly fluctuating demand, compared to the more established currencies.

Currencies of the East African coast

Map of the Swahili coast

On the East African coast, coins of copper, silver, and gold were issued by the rulers of various city-states beginning at Shanga in the 9th century, and later at Pemba, Zanzibar, Kilwa, Mogadishu, Mombasa, and Lamu. Silver coins were more common on the northern coast, while copper coins were mostly found on the southern coast. Most had a limited circulation, and almost all were found on the Swahili coast, except a handful of Kilwa coins, which have been found at Great Zimbabwe, Oman, and northern Australia.

The coins did not conform to the conventions of Islamic coinage—they did not carry either date, mint, or a reference to the caliph. Unlike other Islamic coins, Swahili issues did not conform to a weight standard, but instead derived their value from the ways that the coins were used. Many stayed in circulation long after they were issued, and some were found alongside cowrie shells and beads, indicating that use of multiple currencies in cities which didnt mint coins. Some copper coins were clipped for use in smaller transactions.36

The Mtambwe Mkuu hoard of silver coins, Pemba Island, Tanzania. Image by S. Wynne-Jones.

Copper coins and carnelian beads from Songo Mnara, Tanzania. Image by J. Perkins et al.

Sustained minting of Swahili coins continued until the 15th century, when European intrusions into the Swahili world promoted the circulation of international coins, such as Spanish piasters and Maria Theresa thalers. Coining on the coast resurfaced sporadically in later periods, such as in Mombasa in the 17th-19th century, although foreign issues remained predominant.

During the 19th century, Thalers were used as a unit of account in Kilwa, Lamu, Pemba, and Mombasa, whereas in Zanzibar, it was used as a means of exchange and as a store of value. Owing to the lack of small denomination coins, in the coastal markets broken sums were generally paid in fixed measures of grain.

The coins of 19th-century Mombasa were put into circulation at the value of one kibaba (small basket) of grain, in relation to the piaster. In Zanzibar, one thaler was bought at 40 measures of corn (one measure corresponding to 5–7 pounds). The last coins issued in the Swahili world before the European partition were ordered by Sultan Barghash in the 1880s.37

Gold coins from Kilwa Kisiwani, 14th century, Tanzania. Image by Helen Brown.

Being commodities, cloth, cowries, and glass beads were also fungible items, and once they left economic circles, they could acquire various social, ritual, and cultural meanings.

In the kingdoms of Kongo and Loango, luxury cloth was used as burial shrouds for the wealthy elites. 17th to 19th century accounts of burials in Loango describe procedures that varied with the rank or wealth of the individual, with a mourning period lasting several weeks during which large quantities of cloth were collected to form a massive coffin that at times required dozens of men and a large wagon to carry.

Cowries were used in Buganda as bride wealth, and in the religious practices of societies near Lake Tanganyika. Gold dust, copper bars, and imported brassware were melted down and fashioned into jewellery across many societies in South-East Africa, such as the Zulu, Shona, and Swahili.

And on the East African coast, copper coins were pierced and transformed into jewelry, while others were left near important tombs by the relatives of the buried individuals.

Many of these currencies remained in circulation long after the imposition of colonial rule, surviving in informal trade and other social contexts, before they were ultimately displaced by modern fiat money.

Skirt made from glass beads, ca. 1850 Xhosa kingdom, South Africa. NMVW.

18th century engraving showing the funeral process of Andris Poucouta, a Mafouk of Cabinda on the Loango coast, made by Louis de Grandpre.

Coins from Songo Mnara, Tanzania. including two clipped coins and a pierced coin. Image by S. Wynne-Jones and J. Fleisher

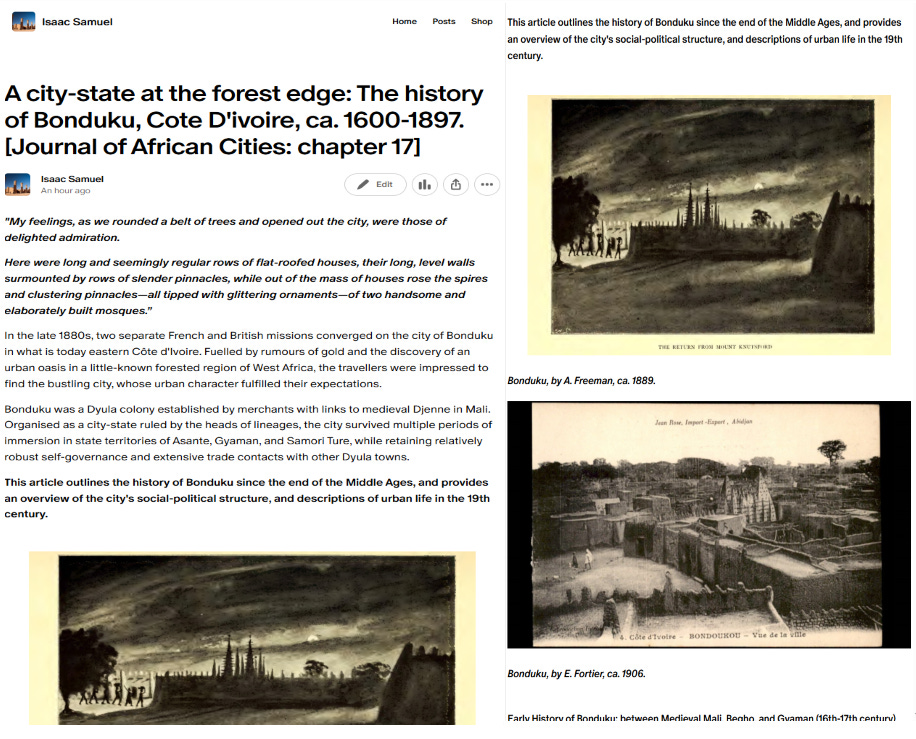

At the end of the Middle Ages, a group of merchants from the Mali empire established a trade colony at the edge of the forest in Côte d’Ivoire, which eventually grew into the city of Bonduku.

The city of Bonduku became a major hub whose distinctive cultural tradition and architecture presented a stark contrast to its rural hinterland. The history of Bonduku is the subject of my latest Patreon article

Please subscribe to read more about it here and support this newsletter:

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 By John K. Thornton, pg 34

Esmeraldo de Situ Orbis by Pacheco Pereira, translated by George H. T. Kimble, pg 145

Early Kongo-Portuguese relations pg 187, 191, n.49, Afonso I Mvemba a Nzinga, King of Kongo: His Life and Correspondence By John K. Thornton, pg 110, n. 48

Africa Counts: Number and Pattern in African Cultures By Claudia Zaslavsky, pg 86-87

Garcia de Orta: Série de geografia, Volumes 10-13, pg 29

Textiles: production, trade and demand, edited by Maureen Fennell Mazzaoui, pg 267-268

The Mbundu and neighbouring peoples of Central Angola under the Influence of Portuguese Trade and Conquest by D Birmingham, pg 146-147, 201, Textiles: production, trade and demand, edited by Maureen Fennell Mazzaoui, pg 272, n. 52, 56.

Power, Cloth and Currency on the Loango Coast by Phyllis M. Martin pg 1-4, The External Trade of the Loango Coast, 1576-1870: The Effects of Changing Commercial Relations on the Vili Kingdom of Loango by Phyllis M. Martin pg 39-40

The Kingdom of Kongo By Anne Hilton, pg 106

The Kingdom of Kongo: Civil War and Transition, 1641-1718 by John Thornton, pg 25, 33

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 By John K. Thornton, pg 198-197

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 By John K. Thornton, pg 290, Kongo in the Age of Empire, 1860–1913: The Breakdown of a Moral Order By Jelmer Vos pg 113

‘Eastern Ethiopia’ by Frair João dos Santos (d. 1622), In ‘Records of South-Eastern Africa: Collected in Various Libraries and Archive Departments in Europe, Volume 7’ by George McCall Theal, pg 269-270. Volume 8 of ‘Documentos sobre os portugueses em Moçambique e na Africa central, 1497-1840: 1561-1588’ Pg 273

An archaeological study of the Zimbabwe culture capital of Khami pg 14, 55, 166-167, New Perspectives on the Political Economy of Great Zimbabwe pg 13-16, Butua and the end of an era pg 19, 30, 229-230

New Perspectives on the Political Economy of Great Zimbabwe by Shadreck Chirikure. The technology of tin smelting in the Rooiberg Valley, Limpopo Province, South Africa, ca. 1650–1850 CE by Shadreck Chirikure

Lead isotopic provenance of some coins and other bronze items from an early Swahili site in Ibo Island (northern Mozambique) by Ignacio Montero-Ruiz et al.

Dating the Mapungubwe Hill Gold by S. Woodborne, M. Pienaar & S. Tiley-Nel

Gold in the Southern African Iron Age by Andrew Oddy

Quirimbas islands (Northern Mozambique) and the Swahili gold trade by Marisa Ruiz-Galvez

Rivers of Gold by H. Ellert, pg 152, Christianity South of the Zambezi, Volume 2 by Anthony J. Dachs, pg 19

The Economics of the Zambezi Missions, 1580-1759 by W. F. Rea, pg 85, n. 166

Volume 8 of Documentos sobre os portugueses em Moçambique e na Africa central, 1497-1840: 1561-1588, Pg 391

Crafting Identity in Zimbabwe and Mozambique By Elizabeth MacGonagle pg 71-73, Africa’s Development in Historical Perspective edited by Emmanuel Akyeampong, Robert H. Bates, Nathan Nunn, James Robinson pg 268-269, The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 4 pg 388

Copper, Trade and Polities: Exchange Networks in Southern Central Africa in the 2nd Millennium CE. Nicolas Nikis & Alexandre Livingstone Smith

Provenancing Central African copper croisettes: A first chemical and lead isotope characterisation of currencies in Central and Southern Africa by Frederik W. Rademakers et al.

The Rainbow and the Kings by Thomas O. Reefe, Thomas Q. Reefe, pg 95, 172. Kingdoms and Associations: Copper’s Changing Political Economy during the Nineteenth Century David M. Gordon

Provenancing Central African copper croisettes: A first chemical and lead isotope characterisation of currencies in Central and Southern Africa by Frederik W. Rademakers

Indigenous Metal Melting and Casting in Southern Africa by Duncan Miller. Red Gold of Africa: Copper in Precolonial History and Culture By Eugenia W. Herbert pg 191-195, Breaking Ground: Hoes in Precolonial South Africa—Typology, Medium of Exchange and Symbolic Value by Abigail Joy Moffett, Tim Maggs and Johnny van Schalkwyk. 19th century glass trade beads : from two Zulu royal residences. by SJ Saitowitz,

The lands of Cazembe: Lacerda’s journey to Cazembe in 1798 by Antonio Gamitto

Political Power in Pre-colonial Buganda: Economy, Society & Warfare in the Nineteenth Century by Richard J. Reid, pg 144-147. Currencies of the Indian Ocean World edited by Steven Serels, Gwyn Campbell, Pg 80-81

‘A recognized currency in beads’. Glass Beads as Money in 19th-Century East Africa: the Central Caravan Road by Karin Pallaver

To the Central African Lakes and Back: The Narrative of the Royal Geographical Society’s East Central African Expedition, 1878-80, by Joseph Thomson, (Searle, 1888) pg 90-91

The Lake Regions of Central Africa: A Picture of Exploration By Sir Richard Francis Burton

From Venice to East Africa: History, uses, and meanings of glass beads by Karin Pallaver pg 202

From Venice to East Africa: History, uses, and meanings of glass beads by Karin Pallaver pg 209-214. Domesticating the World: African Consumerism and the Genealogies of Globalization by Jeremy Prestholdt pg 64

The Swahili World edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria Jean LaViolette, pg 448-451. The Indian Ocean and Swahili Coast coins, international networks, and local developments by John Perkins. Coins and other currencies on the Swahili coast by Stephanie Wynne-Jones and Jeffrey Fleisher. Coins in Context: Local Economy, Value and Practice on the East African Swahili Coast by Stephanie Wynne-Jones & Jeffrey Fleisher. A deposit of Kilwa-type coins from Songo Mnara, Tanzania by John Perkins et al.

The Swahili World edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria Jean LaViolette, pg 453-455

A central truth in economic and trading systems is that any given object has precisely the value assigned to it by any two or more people engaged in trading it - whether acquiring or selling that object is the purpose of the exchange or that object is itself a substitute for the desired product or good.

How common were wheeled carriages in sub Saharan Africa like the on in the engraving?